Archive for the ‘‘THE PERENNIAL PHILOSOPHY’ revisited’ Category

‘THE PERENNIAL PHILOSOPHY’ revisited

JOHN ROBERT COLOMBO reopens his old copy

of Aldous Huxley’s important study

I have always had a soft spot in my heart for a book that I bought by mail from Samuel Weiser Inc., the well-known, used-book dealer, then located in New York City. I made the purchase on 18 July 1957. I know the date of the original purchase because in a firm hand I had inscribed the date on the back end-page of the coveted volume. I read the book shortly after buying it, as its fame had preceded my purchase of this title, and since then its spine has graced many a bookshelf in the houses in which I have since lived and worked.

The edition that I have of “The Perennial Philosophy” is cloth-bound (printers used real cloth in those days) and its distinctive colour (russet) has yet to fade. The edition measures 5.25″ by 8.25″ and there are eight preliminary pages followed by the text of 360 pages. In design the pages are unpretentious and hence attractive to behold, and because they are set in largish type they are quite easy to read. The pages are sewn rather than glued and the paper is cream-coloured and hence it shows no evidence of its age; there is not a mottle in sight. The edition in question is the first edition, or close to it, published by Huxley’s regular London-based publishing house, Chatto & Windus, in 1946. I wish I had the dust jacket but it was not supplied by Samuel Weiser.

The pages may not show their years, but in a great many ways the text of the book is quite dated, almost alarmingly so. Now, Aldous Huxley is an interesting writer who is best (and worst) described as an intellectual, a highbrow, or, to use the terminology that he employs, a “cerebrotonic.” As he explains in these pages, “Cerebrotonics hate to slam doors or raise their voices, and suffer acutely from the unrestrained bellowing and trampling of the somatotonic …. The emotional gush of the viscerotonic strikes them as offensively shallow and even insincere.”

With this vocabulary he is employing the psychology of human types elaborated by the American psychologist William Sheldon, a scheme long out of fashion yet dear to the hearts of students of consciousness studies everywhere. Nothing dates quite as quickly as psychological terminology. Psychical and spiritual terminology like “intellectual centre,” “emotional centre, “moving centre,” etc., seems to age hardly at all!

Huxley died at the age of sixty-nine in 1963, the same day that John F. Kennedy was assassinated. There is about the life and death of the English author and intellectual the sense of the dashing of high hopes, analogous to the early death of the American president. Huxley advanced from being a nihilist in his youth to a psychedelicist in his age. Where would the next twenty or thirty years have taken him? Perhaps to the altar of the nearest Episcopal church. The question is unanswerable.

The jury is still out about which genre is the best for Huxley: Was he finer as a literary artist (remember Point Counterpoint and Brave New World, the novels that ensured his reputation) or was he finer as a literary essayist (required reading in the 1950s was The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell, short memoirs that did so much to mark the coming of age of the psychedelic revolution of the late Fifties and early Sixties)? It matters little, but accompanying his migration from England to California was his move the ironic to the mythic levels of discourse, almost as a matter of course.

Everyone interested in consciousness studies has heard of his study called The Perennial Philosophy. It bears such a prescient and memorable title. His use of the title has preempted its use by any other author, neuropsychologist, Traditionalist, or enthusiast for the New Age. The book so nobly named did much to romanticize the notion of “perennialism” and to cast into the shade such long-established timid Christian notions of “ecumenicism” (Protestants dialoguing with Catholics, etc.) or “inter-faith” meetings (Christians encountering non-Christians, etc.). Who would cared about the beliefs of Baptists when one could care about the practices of Tibetans?

Huxley did his best to popularize serious speculation about the nature of man and the constitution of the universe, largely prompted by such speculations found in Vedanta. He was marked by his mid-life study of texts basic to Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christian mysticism. He knew about shamanism and perhaps about sorcery, alchemy, witchcraft, or wicca, but these aspects of his inquiries went unnoticed in his text. The New Age had yet to dawn.

What precisely is what he calls “the perennial philosophy”? Huxley answers this broad question in an even broader way on the first page of the Introduction to his book. His answer is surprisingly wordy, though his exposition is characteristically well organized. Here goes:

“Philosophia Perennis – the phrase was coined by Leibniz; but the thing – the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man’s final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being – the thing is immemorial and universal.

“Rudiments of the Perennial Philosophy may be found among the traditionary lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions. A version of this Highest Common Factor in all preceding and subsequent theologies was first committed to writing more than twenty-five centuries ago, and since that time the inexhaustible theme has been treated again and again, from the standpoint of every religious tradition and in all the principal languages of Asia and Europe.”

I like the idea of “this Highest Common Factor” because it begs a corresponding discussion on “a Lowest Common Multiple.” Huxley avoids this but then states, neatly, “Knowledge is a function of being.” I could quote more (and will, later), but the sentences that bring his Introduction to a conclusion are worth quoting here and now: “If one is not oneself a sage or saint, the best thing one can do, in the field of metaphysics, is to study the works of those who were, and who, because they had modified their merely human mode of being, were capable of a more than merely human kind and amount of knowledge.”

I first read these words some forty years ago when I was wowed and won by them. Rereading them now I have second thoughts. The book’s chapters are organized by theme, advancing from Chapter 1, “That Art Thou,” to Chapter 27, “Contemplation, Action and Social Utility.”

I was not really surprised to find that the book’s contents are quite dated, but I was really surprised to find its arguments and rhetoric quite limited in appeal. The book is hortatory in style and substance, less of a psychological probing and more a hectoring that I had remembered it to be.

The book’s six-page, double-column index is extensive but unscholarly, and there was no need for him to index the word “consciousness” or its cognate terms “unconscious” and “subconscious” because these subjects are given no special treatment. There is no reference to Sigmund Freud; the single reference to Carl Jung draws attention to the psychologist’s use (his coinage, really) of the terms “introvert” and “extravert.” The contribution of Mircea Eliade, the multilingual scholar of shamanism, goes unmentioned. G.I. Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky (whose lectures Huxley attended at Colet Gardens in London) go unremarked.

As well, there is no reference to R.M. Bucke’s monumental, turn-of-the-century tome titled “Cosmic Consciousness,” and details about consciousness-raising or altering drugs and psychedelia in general are all in Huxley’s future. Yet the psychologist William James had much to say about chemically inducted altered states, and also about the field of psychical research in general, to which James donated twenty years of his professional life, speculating on the characteristics of the various levels of consciousness. All these go unappreciated except for one passing reference to James, as if to acknowledge his absence.

“The Perennial Philosophy” is essentially an anthology of short passages taken from traditional Eastern texts and the writings of Western mystics, organized by subject and topic, with short connecting commentaries. No specific sources are given. Paging through the index gives the reader (or non-reader) an idea of who and what Huxley has taken seriously. Here are the entries in the index that warrant two lines of page references or more:

Aquinas, Augustine, St. Bernard, Bhagavad-Gita, Buddha, Jean Pierre Camus, St. Catherine, Christ, Chuang Tzu, “Cloud of Unknowing,” Contemplation, Deliverance, Desire, Eckhart (five lines, the most quoted person), Eternity, Fénelon, François de Sales, Godhead, Humility, Idolatry, St. John of the Cross, Knowledge, Lankavatara Sutra, William Law (another four lines), Logos, Love, Mahayana, Mind, Mortification, Nirvana, Perennial Philosophy (six lines, a total of 40 entries in all), Prayer, Rumi, Ruysbroeck, Self, Shankara, Soul, Spirit, “Theologia Germanica,” Truth, Upanishads (six different ones are quoted), Will, Words.

Painfully absent from these pages are Huxley’s mordant wit and insights into human nature. It is as if his quicksilverish intelligence has been put on hold or has found itself in a deep freeze of his own making. When it comes to selecting short and sometimes long quotations, he is no compiler like John Bartlett of quotation fame, but he does find time to make a few deft personal observations.

Here is a suggestion from Chapter 3, “Personality, Sanctity, Divine Incarnation”:

“But surely people would think twice about making or accepting this affirmation if, instead of ‘personality,’ the word employed had been its Teutonic synonym, ‘selfness.’ For ‘selfness,’ though it means precisely the same, carries none of the high-class overtones that go with ‘personality.’ On the contrary, its primary meaning comes to us embedded, as it were, in discords, like the note of a cracked bell.”

Chapter 7, “Truth,” offers the following gem:

“Beauty in art or nature is a matter of relationships between things not in themselves intrinsically beautiful. There is nothing beautiful, for example, about the vocables ‘time,’ or ‘syllable.’ But when they are used in such a phrase as ‘to the last syllable of recorded time,’ the relationship between the sound of the component words, between our ideas of the things for which they stand, and between the overtones of association with which each word and the phrase as a whole are charged, is apprehended, by a direct and immediate intuition, as being beautiful.”

Chapter 12, “Time and Eternity,”gives the following caveat about the relative absence of Eastern literature in Western translation:

“This display of what, in the twentieth century, is an entirely voluntary and deliberate ignorance is not only absurd and discreditable; it is also socially dangerous. Like any other form of imperialism, theological imperialism is a menace to permanent world peace. The reign of violence will never come to an end until, first, most human beings accept the same, true philosophy of life; until, second, this Perennial Philosophy is recognized as the highest factor common to all the world religions; until, third, the adherents of every religion renounce the idolatrous time-philosophies, with which, in their own particular faith, the Perennial Philosophy of eternity has been overlaid; until, fourth, there is a world-wide rejection of all the political pseudo-religions, which place man’s supreme good in future time and therefore justify and commend the commission of every sort of present iniquity as a means to that end. If these conditions are not fulfilled, no amount of political planning, no economic blue-prints however ingeniously drawn, can prevent the recrudescence of war and revolution.”

That passage was written during the Battle of Britain, so it is perhaps understandable that the essayist has become the preacher, the novelist the moralist. The text of his sermonizing seems to be that knowing about the perennial philosophy will, ipso facto, without further ado, without any other effort on anyone’s behalf, transform man’s bellicose nature into something finer and better!

As a reader of “The Perennial Philosophy,” and now its re-reader, I must admit to experiencing a sense of exhilaration the first time round – and to experiencing a sense of anticlimax and even dismay the second time round.

Today the book seems too arch and so idiosyncratic! As well, I could not help but note the author’s lack of generosity and his unwillingness to express any sense of indebtedness to his predecessors. He fails to note two earlier, landmark publications in his chosen field: William James’s “The Varieties of Religious Experience” (1902) and Evelyn Underhill’s “Mysticism” (1911).

Yet these influential works were written decades before the appearance of Huxley’s book; indeed, they have aged far less obviously that has Huxley’s. As well, Underhill refers to James in her book, if only to argue with his thesis, but Huxley’s ignores both of them and their arguments to develop his own semi-thesis. In point of fact, the bibliography has an entry for “Mysticism” (with a reprint year of 1924, instead of 1911, the original year of publication).

In passing, it is interesting to note that the same bibliography draws attention to the publication of three books that were written by René Guénon, though no editorial use is made of even one of these – or of the writings of the leading Traditionalists: A.K. Coomaraswamy, Frithjof Schuon, Titus Burckhardt. To this cabal should be added Whitall Perry, whose tome A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom (1971, 1986, 2000) is rightfully regarded as the principal anthology in this field.

To the extent that he was a follower of any mainstream religion, Huxley was a student of the Hindu system of thought known as Vedanta, which was making its American beachhead in Los Angeles, California, close to Huxley’s residence in Malibu. The text offers four references to Vedanta, the last one being the following observation:

“The shortest _mantram_ is OM – a spoken symbol that concentrates within itself the whole Vedanta philosophy. To this and other _mantrams_ Hindus attribute a kind of magical power. The repetition of them is a sacramental act, conferring grace _ex opere operato_.”

In summary, Huxley’s book made an immediate impact upon publication and reverberates to this day, but upon examination the concept of the book is more convincing than is the accomplishment; at the same time, the parts are more intriguing than the whole. If it is a landmark study of anything at all, it takes its place in the eclectic division of the syncretistic field variously known as “religious knowledge,” “religious studies,” “comparative religion,” “Near Eastern studies,” “history of religion” – euphemisms abound! – in drawing the attention of English-speaking readers to the rich mother-lode of philosophical, psychological, and metaphysical thought that is to be found in translations of traditional Eastern texts and in the writings of Christian mystics of the past.

One of the meanings of the word “perennial” is “enduring,” and enduring is what this book is. “The Perennial Philosophy” endures in memory. A week or so ago, I took it down from the place it had graced on my bookshelf and dusted it off; later today I will return it to its rightful place. After all, it occupies a special space in my memory … as well as in the memories of its great many readers over the last six decades.

===========

John Robert Colombo is nationally known for his compilations of Canadiana. These include such studies as “Mysterious Canada” and “UFOs over Canada.” He received the Harbourfront Literary Award and holds honourary D.Litt. from York University, Toronto. He is an Associate of the Northrop Frye Centre, Victoria College, University of Toronto. Check his website < www .colombo – plus . ca > .

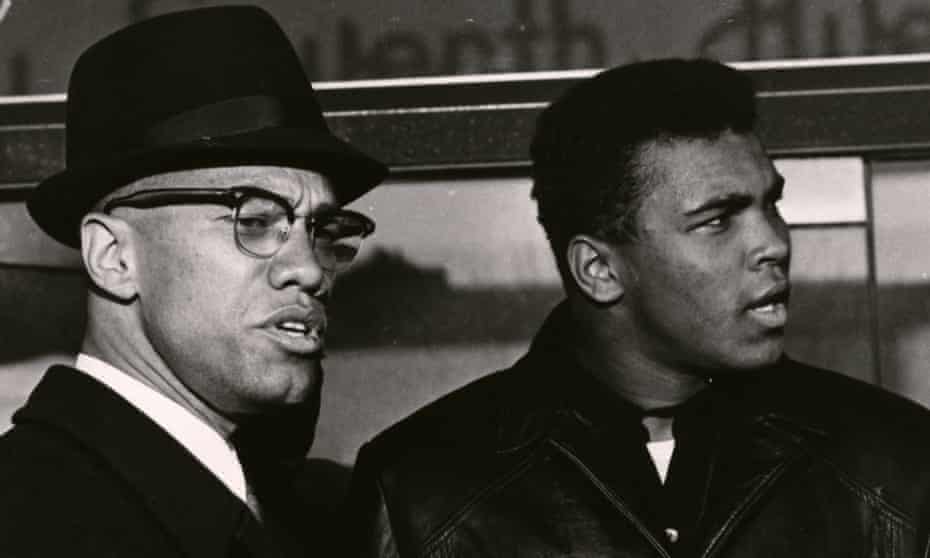

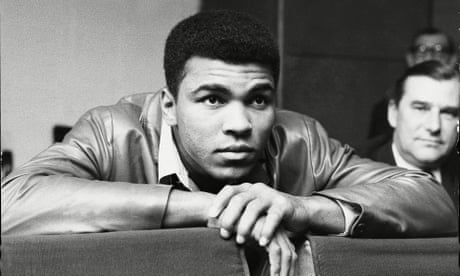

Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali Photograph: Netflix

Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali Photograph: Netflix

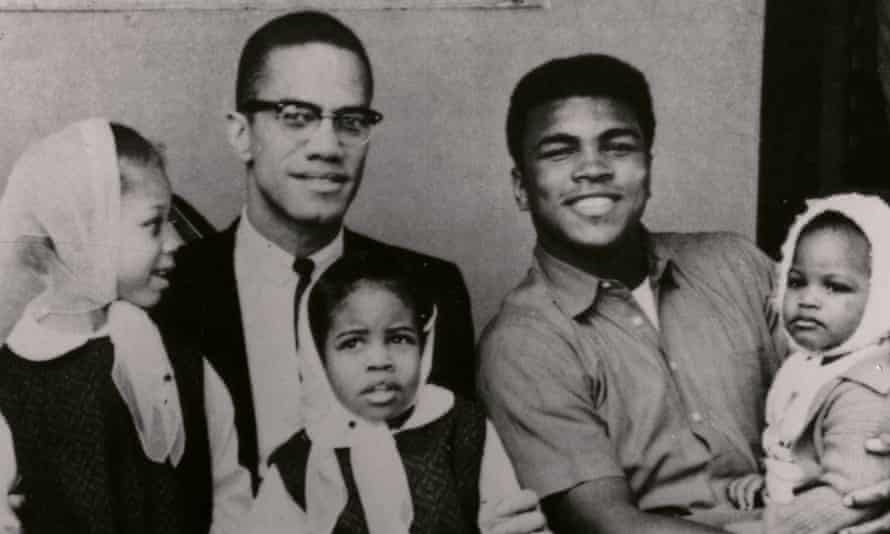

Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali with their children Photograph: Netflix

Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali with their children Photograph: Netflix