A reproduction of the palm-leaf manuscript in Siddham script, originally held at Hōryū-ji Temple, Japan; now located in the Tokyo National Museum at the Gallery of Hōryū—ji Treasure. The original copy may be the earliest extant Sanskrit manuscript dated to the 7th–8th century CE. The Heart Sūtra (Sanskrit: प्रज्ञापारमिताहृदय Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya or Chinese: 心經 Xīnjīng, Tibetan: བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་མ་ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པའི་སྙིང་པོ) is a popular sutra in Mahāyāna Buddhism. In Sanskrit, the title Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya translates as "The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom".

The Sutra famously states, "Form is emptiness (śūnyatā), emptiness is form." It is a condensed exposé on the Buddhist Mahayana teaching of the Two Truths doctrine, which says that ultimately all phenomena are sunyata, empty of an unchanging essence. This emptiness is a 'characteristic' of all phenomena, and not a transcendent reality, but also "empty" of an essence of its own. Specifically, it is a response to Sarvastivada teachings that "phenomena" or its constituents are real.[2]:9

It has been called "the most frequently used and recited text in the entire Mahayana Buddhist tradition." The text has been translated into English dozens of times from Chinese, Sanskrit and Tibetan as well as other source languages.

Summary of the sutra[edit]

In the sutra, Avalokiteśvara addresses Śariputra, explaining the fundamental emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena, known through and as the five aggregates of human existence (skandhas): form (rūpa), feeling (vedanā), volitions (saṅkhāra), perceptions (saṃjñā), and consciousness (vijñāna). Avalokiteśvara famously states, "Form is Emptiness (śūnyatā). Emptiness is Form", and declares the other skandhas to be equally empty—that is, dependently originated.

Avalokiteśvara then goes through some of the most fundamental Buddhist teachings such as the Four Noble Truths, and explains that in emptiness none of these notions apply. This is interpreted according to the two truths doctrine as saying that teachings, while accurate descriptions of conventional truth, are mere statements about reality—they are not reality itself—and that they are therefore not applicable to the ultimate truth that is by definition beyond mental understanding. Thus the bodhisattva, as the archetypal Mahayana Buddhist, relies on the perfection of wisdom, defined in the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra to be the wisdom that perceives reality directly without conceptual attachment, thereby achieving nirvana.

The sutra concludes with the mantra gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā, meaning "gone, gone, everyone gone to the other shore, awakening, svaha."[note 1]

Popularity and stature[edit]

The Heart Sutra engraved on a wall in Mount Putuo, bodhimanda of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva. The five large red characters read "guān zì zài pú sà" in Mandarin, one of the Chinese names for Avalokiteśvara, which is the beginning of the sutra. The rest of the sutra is in black characters. The Heart Sutra is "the single most commonly recited, copied and studied scripture in East Asian Buddhism."[2][note 2] [note 3] It is recited by adherents of Mahayana schools of Buddhism regardless of sectarian affiliation.[5]:59–60

While the origin of the sutra is disputed by some modern scholars, it was widely known in Bengal and Bihar during the Pala Empire period (c. 750–1200 CE) in India, where it played a role in Vajrayana Buddhism.[7]:239,18–20[note 4] The stature of the Heart Sutra throughout early medieval India can be seen from its title ‘Holy Mother of all Buddhas Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom’[8]:389 dating from at least the 8th century CE (see Philological explanation of the text).[2]:15–16[7]:141,142[note 5]

The long version of the Heart Sutra is extensively studied by the various Tibetan Buddhist schools, where the Heart Sutra is chanted, but also treated as a tantric text, with a tantric ceremony associated with it.[7]:216–238 It is also viewed as one of the daughter sutras of the Prajnaparamita genre in the Vajrayana tradition as passed down from Tibet.[9]:67–69[10]:2[note 6][note 7]

The text has been translated into many languages, and dozens of English translations and commentaries have been published, along with an unknown number of informal versions on the internet.[note 8]

Versions[edit]

There are two main versions of the Heart Sutra: a short version and a long version.

The short version as translated by Xuanzang is the most popular version of adherents practicing East Asian schools of Buddhism. Xuanzang's canonical text (T. 251) has a total of 260 Chinese characters. Some Japanese versions have an additional 2 characters. The short version has also been translated into Tibetan but it is not part of the current Tibetan Buddhist Canon.

The long version differs from the short version by including both an introductory and concluding section, features that most Buddhist sutras have. The introduction introduces the sutra to the listener with the traditional Buddhist opening phrase "Thus have I heard". It then describes the venue in which the Buddha (or sometimes bodhisattvas, etc.) promulgate the teaching and the audience to whom the teaching is given. The concluding section ends the sutra with thanks and praises to the Buddha.

Both versions are chanted on a daily basis by adherents of practically all schools of East Asian Buddhism and by some adherents of Tibetan and Newar Buddhism.[11]

Dating and origins[edit]

The third oldest dated copy of the Heart Sutra, on part of the stele of Emperor Tang Taizong's Foreword to the Holy Teaching, written on behalf of Xuanzang in 648 CE, erected by his son, Emperor Tang Gaozong in 672 CE, known for its exquisite calligraphy in the style of Wang Xizhi (303–361 CE) – Xian's Beilin Museum Earliest extant versions[edit]

The earliest extant dated text of the Heart Sutra is a stone stele dated to 661 CE located at Yunju Temple and is part of the Fangshan Stone Sutra. It is also the earliest copy of Xuanzang's 649 CE translation of the Heart Sutra (Taisho 221); made three years before Xuanzang passed away.[12][13][14][15]:12,17[note 9]

A palm-leaf manuscript found at the Hōryū-ji Temple is the earliest undated extant Sanskrit manuscript of the Heart Sutra. It is dated to c. 7th–8th century CE by the Tokyo National Museum where it is currently kept.[16]:208–209

Source of the Heart Sutra - Nattier controversy[edit]

Jan Nattier (1992) argues, based on her cross-philological study of Chinese and Sanskrit texts of the Heart Sutra, that the Heart Sutra was initially composed in China.[16] The extant Sanskrit text of the Heart Sutra contains a number of Chinese idioms and unidiomatic Sanskrit phrases, suggesting a Chinese original was "back-translated" into Sanskrit.[17] Jayarava Attwood concurs, adding that the text seems to be a "framed extract" of a set of identical passages occurring in Chinese translations of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā and Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā sutras, composed in a Tang Chinese context favoring devotion to Avalokiteśvara, meditative practices involving examination of the skandhas, and dharani chanting.[18]

Fukui, Harada, Ishii and Siu based on their cross-philological study of Chinese and Sanskrit texts of the Heart Sutra and other medieval period Sanskrit Mahayana sutras theorize that the Heart Sutra could not have been composed in China but was composed in India.[8][note 10]:43–44,72–80

Kuiji and Woncheuk were the two main disciples of Xuanzang. Their 7th century commentaries are the earliest extant commentaries on the Heart Sutra; both commentaries, according to Dan Lusthaus and Hyun Choo, contradict Nattier's Chinese origin theory.[5]:27[23]:146–147[note 11] However, Jayarava Attwood systematically disputes all of Lusthaus' examples, illustrating that they refer in fact to various earlier translations of the source texts the Heart Sutra is extract from (primarily the Aṣṭasāhasrikā and Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā), and not some theorized "original Sanskrit text".[24] Attwood also asserts that there is insufficient evidence to confirm that Sanskrit versions of the text were the original, as it just as easily could have been back-translated by Xuanzang into Sanskrit, as the earliest extant Sanskrit versions only appear after the time of his floruit.[25]

Philological explanation of the text[edit]

Historical titles[edit]

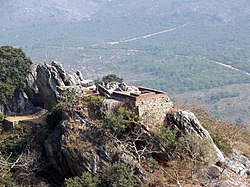

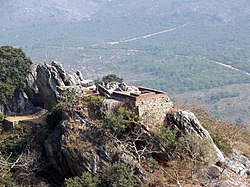

Gridhakuta (also known as Vulture's Peak) located in Rajgir Bihar India (in ancient times known as Rājagṛha or Rājagaha (Pali) - Site where Buddha taught the Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya (Heart Sutra) and other Prajñāpāramitā sutras. The titles of the earliest extant manuscripts of the Heart Sutra all includes the words “hṛdaya” or “heart” and “prajñāpāramitā” or "perfection of wisdom". Beginning from the 8th century and continuing at least until the 13th century, the titles of the Indic manuscripts of the Heart Sutra contained the words “bhagavatī” or "mother of all buddhas" and “prajñāpāramitā”.[note 12]

Later Indic manuscripts have more varied titles.

Titles in use today[edit]

In the western world, this sutra is known as the Heart Sutra (a translation derived from its most common name in East Asian countries). But it is also sometimes called the Heart of Wisdom Sutra. In Tibet, Mongolia and other regions influenced by Vajrayana, it is known as The [Holy] Mother of all Buddhas Heart (Essence) of the Perfection of Wisdom.

In the Tibetan text the title is given first in Sanskrit and then in Tibetan: Sanskrit: भगवतीप्रज्ञापारमिताहृदय (Bhagavatīprajñāpāramitāhṛdaya), Tibetan: བཅོམ་ལྡན་འདས་མ་ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པའི་སྙིང་པོ, Wylie: bcom ldan 'das ma shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa'i snying po English translation of Tibetan title: Mother of All Buddhas Heart (Essence) of the Perfection of Wisdom.[10]:1[note 13]

In other languages, the commonly used title is an abbreviation of Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayasūtraṃ : i.e. The Prajñāhṛdaya Sūtra )(The Heart of Wisdom Sutra). They are as follows: e.g. Korean: Banya Shimgyeong (반야심경 / 般若心經); Japanese: Hannya Shingyō (はんにゃしんぎょう / 般若心経); Vietnamese: Bát-nhã tâm kinh (chữ Nho: 般若心經).

Content[edit]

Various commentators divide this text into different numbers of sections. In the long version, we have the traditional opening "Thus have I heard" and Buddha along with a community of bodhisattvas and monks gathered with Avalokiteśvara and Sariputra at Gridhakuta (a mountain peak located at Rajgir, the traditional site where the majority of the Perfection of Wisdom teachings were given) , when through the power of Buddha, Sariputra asks Avalokiteśvara[27]:xix,249–271[note 14] [28]:83–98 for advice on the practice of the Perfection of Wisdom. The sutra then describes the experience of liberation of the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteśvara, as a result of vipassanā gained while engaged in deep meditation to awaken the faculty of prajña (wisdom). The insight refers to apprehension of the fundamental emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena, known through and as the five aggregates of human existence (skandhas): form (rūpa), feeling (vedanā), volitions (saṅkhāra), perceptions (saṃjñā), and consciousness (vijñāna).

The specific sequence of concepts listed in lines 12–20 ("...in emptiness there is no form, no sensation, ... no attainment and no non-attainment") is the same sequence used in the Sarvastivadin Samyukta Agama; this sequence differs in comparable texts of other sects. On this basis, Red Pine has argued that the Heart Sūtra is specifically a response to Sarvastivada teachings that, in the sense "phenomena" or its constituents, are real.[2]:9 Lines 12–13 enumerate the five skandhas. Lines 14–15 list the twelve ayatanas or abodes.[2]:100 Line 16 makes a reference to the 18 dhatus or elements of consciousness, using a conventional shorthand of naming only the first (eye) and last (conceptual consciousness) of the elements.[2]:105–06 Lines 17–18 assert the emptiness of the Twelve Nidānas, the traditional twelve links of dependent origination.[2]:109 Line 19 refers to the Four Noble Truths.

Avalokiteśvara addresses Śariputra, who was the promulgator of abhidharma according to the scriptures and texts of the Sarvastivada and other early Buddhist schools, having been singled out by the Buddha to receive those teachings.[2]:11–12, 15 Avalokiteśvara famously states, "Form is empty (śūnyatā). Emptiness is form", and declares the other skandhas to be equally empty of the most fundamental Buddhist teachings such as the Four Noble Truths and explains that in emptiness none of these notions apply. This is interpreted according to the two truths doctrine as saying that teachings, while accurate descriptions of conventional truth, are mere statements about reality—they are not reality itself—and that they are therefore not applicable to the ultimate truth that is by definition beyond mental understanding. Thus the bodhisattva, as the archetypal Mahayana Buddhist, relies on the perfection of wisdom, defined in the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra to be the wisdom that perceives reality directly without conceptual attachment thereby achieving nirvana.

All Buddhas of the three ages (past, present and future) rely on the Perfection of Wisdom to reach unexcelled complete Enlightenment. The Perfection of Wisdom is the all powerful Mantra, the great enlightening mantra, the unexcelled mantra, the unequalled mantra, able to dispel all suffering. This is true and not false. The Perfection of Wisdom is then condensed in the mantra with which the sutra concludes: "Gate Gate Pāragate Pārasamgate Bodhi Svāhā" (literally "Gone gone, gone beyond, gone utterly beyond, Enlightenment hail!").[30] In the long version, Buddha praises Avalokiteśvara for giving the exposition of the Perfection of Wisdom and all gathered rejoice in its teaching. Many schools traditionally have also praised the sutra by uttering three times the equivalent of "Mahāprajñāpāramitā" after the end of the recitation of the short version.

The Heart Sūtra mantra in Sanskrit IAST is gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā, Devanagari: गते गते पारगते पारसंगते बोधि स्वाहा, IPA: ɡəteː ɡəteː paːɾəɡəteː paːɾəsəŋɡəte boːdʱɪ sʋaːɦaː, meaning "gone, gone, everyone gone to the other shore, awakening, svaha."[note 15]

Buddhist exegetical works[edit]

China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam[edit]

Two commentaries of the Heart Sutra were composed by pupils of Xuanzang, Woncheuk and Kuiji, in the 7th century.[5]:60 These appear to be the earliest extant commentaries on the text. Both have been translated into English.[23][32] Both Kuījī and Woncheuk's commentaries approach the Heart Sutra from both a Yogācāra and Madhyamaka viewpoint;[5][23] however, Kuījī's commentary presents detailed line by line Madhyamaka viewpoints as well and is therefore the earliest surviving Madhyamaka commentary on the Heart Sutra. Of special note, although Woncheuk did his work in China, he was born in Silla, one of the kingdoms located at the time in Korea.

The chief Tang Dynasty commentaries have all now been translated into English.

Notable Japanese commentaries include those by Kūkai (9th Century, Japan), who treats the text as a tantra,[34] and Hakuin, who gives a Zen commentary.

There is also a Vietnamese commentarial tradition for the Heart Sutra. The earliest recorded commentary is the early 14th century Thiền commentary entitled ‘Commentary on the Prajñāhṛdaya Sutra’ by Pháp Loa.[36]:155,298[note 16]

All of the East Asian commentaries are commentaries of Xuanzang's translation of the short version of the Heart Sutra. Kukai's commentary is purportedly of Kumārajīva's translation of the short version of the Heart Sutra;but upon closer examination seems to quote only from Xuanzang's translation.[34]:21,36–37

Major Chinese language Commentaries on the Heart Sutra| # | English Title [note 17] | Taisho Tripitaka No.[38] | Author [note 18] | Dates | School |

|---|

| 1. | Comprehensive Commentary on the Prañāpāramitā Heart Sutra[11] | T1710 | Kuiji | 632–682 CE | Yogācāra |

| 2. | Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sutra Commentary[23] | T1711 | Woncheuk or (pinyin :Yuance) | 613–692 CE | Yogācāra |

| 3. | Brief Commentary on the Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sutra[2]:passim[39] | T712 | Fazang | 643–712 CE | Huayan |

| 4. | A Commentary on the Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sutra[2]:passim | M522 | Jingmai | c. 7th century[40]:7170 | |

| 5. | A Commentary on the Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sutra[2]:passim | M521 | Huijing | 715 CE | |

| 6. | Secret Key to the Heart Sutra[34]:262–276 | T2203A | Kūkai | 774–835 CE | Shingon |

| 7. | Straightforward Explanation of the Heart Sutra[2]:passim[41]:211–224 | M542 | Hanshan Deqing | 1546–1623 CE[40]:7549 | Chan Buddhism |

| 8. | Explanation of the Heart Sutra[2]:passim | M1452 (Scroll 11) | Zibo Zhenke | 1543–1603 CE[40]:5297 | Chan Buddhism |

| 9. | Explanation of the Keypoints to the Heart Sutra[2]:74 | M555 | Ouyi Zhixu | 1599–1655 CE[40]:6321 | Pure Land Buddhism |

| 10. | Zen Words for the Heart | B021 | Hakuin Ekaku | 1686–1768 CE | Zen |

Eight Indian commentaries survive in Tibetan translation and have been the subject of two books by Donald Lopez.[7] These typically treat the text either from a Madhyamaka point of view, or as a tantra (esp. Śrīsiṃha). Śrī Mahājana's commentary has a definite "Yogachara bent".[7] All of these commentaries are on the long version of the Heart Sutra. The Eight Indian Commentaries from the Kangyur are (cf first eight on chart):

Indian Commentaries on the Heart Sutra from Tibetan and Chinese language Sources| # | English Title[note 19] | Peking Tripitaka No.[43][44][45] | Author / Dates |

|---|

| 1. | Vast Explanation of the Noble Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom | No. 5217 | Vimalamitra (b. Western India fl. c. 797 CE – 810 CE) |

| 2, | Atīśa's Explanation of the Heart Sutra | No. 5222 | Atīśa (b. Eastern India, 982 CE – 1045 CE) |

| 3. | Commentary on the 'Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom | No. 5221 | Kamalaśīla (740 CE – 795 CE) |

| 4. | Commentary on the Heart Sutra as Mantra | No. 5840 | Śrīsiṃha (probably 8th century CE)[7]:82[note 20] |

| 5. | Explanation of the Noble Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom | No. 5218 | Jñānamitra (c. 10th–11th century CE)[46]:144 |

| 6. | Vast Commentary on the Noble Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom | No. 5220 | Praśāstrasena |

| 7. | Complete Understanding of the Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom | No. 5223 | Śrī Mahājana (probably c. 11th century)[47]:91 |

| 8. | Commentary on the Bhagavati (Mother of all Buddhas) Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra, Lamp of the Meaning | No. 5219 | Vajrāpaṇi (probably c. 11th century CE)[47]:89 |

| 9. | Commentary on the Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom | M526 | Āryadeva (or Deva) c. 10th century[note 21] |

There is one surviving Chinese translation of an Indian commentary in the Chinese Buddhist Canon. Āryadeva's commentary is on the short version of the Heart Sutra.[26]:11,13

Besides the Tibetan translation of Indian commentaries on the Heart Sutra, Tibetan monk-scholars also made their own commentaries. One example is Tāranātha's A Textual Commentary on the Heart Sutra.

In modern times, the text has become increasingly popular amongst exegetes as a growing number of translations and commentaries attest. The Heart Sutra was already popular in Chan and Zen Buddhism, but has become a staple for Tibetan Lamas as well.

Selected English translations[edit]

The first English translation was presented to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1863 by Samuel Beal, and published in their journal in 1865. Beal used a Chinese text corresponding to T251 and a 9th Century Chan commentary by Dàdiān Bǎotōng (大顛寶通) [c. 815 CE].[48] In 1881, Max Müller published a Sanskrit text based on the Hōryū-ji manuscript along an English translation.[49]

There are more than 40 published English translations of the Heart Sutra from Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan, beginning with Beal (1865). Almost every year new translations and commentaries are published. The following is a representative sample.

Recordings[edit]

The Heart Sūtra has been set to music a number of times.[50] Many singers solo this sutra.[51]

- The Buddhist Audio Visual Production Centre (佛教視聽製作中心) produced a Cantonese album of recordings of the Heart Sūtra in 1995 featuring a number of Hong Kong pop singers, including Alan Tam, Anita Mui and Faye Wong and composer by Andrew Lam Man Chung (林敏聰) to raise money to rebuild the Chi Lin Nunnery.[52]

- Malaysian Imee Ooi (黄慧音) sings the short version of the Heart Sūtra in Sanskrit accompanied by music entitled 'The Shore Beyond, Prajna Paramita Hrdaya Sutram', released in 2009.

- Hong Kong pop singers, such as the Four Heavenly Kings sang the Heart Sūtra to raise money for relief efforts related to the 921 earthquake.[53]

- An Mandarin version was first performed by Faye Wong in May 2009 at the Famen Temple for the opening of the Namaste Dagoba, a stupa housing the finger relic of Buddha rediscovered at the Famen Temple.[54] She has sung this version numerous times since and its recording was subsequently used as a theme song in the blockbusters Aftershock (2010)[55][56] and Xuanzang (2016).[57]

- Shaolin Monk Shifu Shi Yan Ming recites the Sutra at the end of the song "Life Changes" by the Wu-Tang Clan, in remembrance of the deceased member ODB.

- The outro of the b-side song "Ghetto Defendant" by the British first wave punk band The Clash also features the Heart Sūtra, recited by American beat poet Allen Ginsberg.

- A slightly edited version is used as the lyrics for Yoshimitsu's theme in the PlayStation 2 game Tekken Tag Tournament. An Indian styled version was also created by Bombay Jayashri, titled Ji Project. It was also recorded and arranged by Malaysian singer/composer Imee Ooi. An Esperanto translation of portions of the text furnished the libretto of the cantata La Koro Sutro by American composer Lou Harrison.[58]

- The Heart Sūtra appears as a track on an album of sutras "performed" by VOCALOID voice software, using the Nekomura Iroha voice pack. The album, Syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism by VOCALOID,[59] is by the artist tamachang.

- Toward the end of the opera The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs by Mason Bates the character inspired by Kōbun Chino Otogawa sings part of the Heart Sūtra to introduce the scene in which Steve Jobs weds Laurene Powell at Yosemite in 1991.

- Part of the Sutra can be heard on Shiina Ringo's song 鶏と蛇と豚 (Gate of Living), from her studio album Sandokushi (2019) [60]

Popular culture[edit]

In the centuries following the historical Xuanzang, an extended tradition of literature fictionalizing the life of Xuanzang and glorifying his special relationship with the Heart Sūtra arose, of particular note being the Journey to the West[61] (16th century/Ming dynasty). In chapter nineteen of Journey to the West, the fictitious Xuanzang learns by heart the Heart Sūtra after hearing it recited one time by the Crow's Nest Zen Master, who flies down from his tree perch with a scroll containing it, and offers to impart it. A full text of the Heart Sūtra is quoted in this fictional account.

In the 2003 Korean film Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter...and Spring, the apprentice is ordered by his Master to carve the Chinese characters of the sutra into the wooden monastery deck to quiet his heart.[62]

The Sanskrit mantra of the Heart Sūtra was used as the lyrics for the opening theme song of the 2011 Chinese television series Journey to the West.[63]

The 2013 Buddhist film Avalokitesvara, tells the origins of Mount Putuo, the famous pilgrimage site for Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva in China. The film was filmed onsite on Mount Putuo and featured several segments where monks chant the Heart Sutra in Chinese and Sanskrit. Egaku, the protagonist of the film, also chants the Heart Sutra in Japanese.[64]

In the 2015 Japanese film I Am a Monk, Koen, a twenty-four year old bookstore clerk becomes a Shingon monk at the Eifuku-ji after the death of his grandfather. The Eifuku-ji is the fifty-seventh temple in the eighty-eight temple Shikoku Pilgrimage Circuit. He is at first unsure of himself. However, during his first service as he chants the Heart Sutra, he comes to an important realization.[65]

Bear McCreary recorded four Japanese-American monks chanting in Japanese, the entire Heart Sutra in his sound studio. He picked a few discontinuous segments and digitally enhanced them for their hypnotic sound effect. The result became the main theme of King Ghidorah in the 2019 film Godzilla: King of the Monsters.[66]

Influence on western philosophy[edit]

Schopenhauer, in the final words of his main work, compared his doctrine to the Śūnyatā of the Heart Sūtra. In Volume 1, § 71 of The World as Will and Representation, Schopenhauer wrote: "…to those in whom the will [to continue living] has turned and has denied itself, this very real world of ours, with all its suns and Milky Ways, is — nothing."[67] To this, he appended the following note: "This is also the Prajna–Paramita of the Buddhists, the 'beyond all knowledge,' in other words, the point where subject and object no longer exist."[68]

See also[edit]

- ^ This is just one interpretation of the meaning of the mantra. There are many others. Traditionally mantras were not translated.

- ^ Pine :

*On p 36-7: "Chen-k'o [Zibo Zhenke or Daguan Zhenke (one of the four great Buddhist Masters of the late Ming Dynasty - member of the Chan sect] says 'This sutra is the principal thread that runs through the entire Buddhist Tripitaka. Although a person's body includes many organs and bones, the heart is the most important.' - ^ Storch :

*On p 172: "Near the Foguangshan temple in Taiwan, one million handwritten copies of the Heart-sutra were buried in December of 2011. They were interred inside a golden sphere by the seat of a thirty-seven-meter-tall bronze statue of the Buddha; in a separate adjacent stupa, a tooth of the Buddha had been buried a few years earlier. The burial of one million copies of the sutra is believed to having created gigantic karmic merit for the people who transcribed it, as well as for the rest of humanity." - ^ Lopez Jr.:

* On p 239: "We can assume, at least, that the sutra was widely known during the Pala period (c. 750–1155 in Bengal and c. 750–1199 in Bihar)."

* On pp 18–20 footnote 8: "...it suggests that the Heart Sutra was recited at Vikramalaśīla (or Vikramashila)(located in today's Bihar, India) and Atisa (982 CE – 1054 CE) appears to be correcting his pronunciation [Tibetan monks visiting Vikramalaśīla – therefore also an indication of the popularity of the Heart Sutra in Tibet during the 10th century] from ‘’ha rūpa ha vedanā’’ to ‘’a rūpa a vedanā’’ to, finally, the more familiar ‘’na rūpa na vedanā’’, saying that because it is the speech of Avalokita, there is nothing wrong to saying ‘’na’’." - ^ Lopez Jr.:

Jñānamitra [the medieval Indian monk–commentator c. 10th–11th Century] wrote in his Sanskrit commentary entitled 'Explanation of the Noble Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom' (Āryaprajñāpāramitāhṛdayavyākhyā), "There is nothing in any sutra that is not contained in the Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom. Therefore it is called the sutra of sutras."

Jñānamitra also said regarding the Sanskrit title of the Heart Sutra 'bhagavatīprajñāpāramitāhṛdayaṃ' and the meaning of the word bhagavatī,"With regard to [the feminine ending] 'ī', all the buddhas arise from practicing the meaning of the perfection of wisdom. Therefore, since the perfection of wisdom comes to be the mother of all buddhas, [the feminine ending] 'ī' is [used]. - ^ Sonam Gyaltsen Gonta : 在佛教教主釋迦牟尼佛(釋尊)對弟子們講述的眾多教義中,《般若經》在思想層面上是最高的。....而將《大般若經》的龐大內容、深遠幽玄本質,不但毫無損傷反而將其濃縮在極精簡扼要的經文中,除了《般若心經》之外沒有能出其右的了...(transl: Among all the teachings taught by Sakyamuni Buddha to his disciples, the highest is the prajñāpāramitā....there are no works besides the Heart Sutra that even comes close to condensing the vast contents of the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra's [the name of a Chinese compilation of complete prajñāpāramitā sutras having 16 sections within it] far-reaching profundity into an extremely concise form without any lost in meaning...

- ^ The Prajñāpāramitā genre is accepted as Buddhavacana by all past and present Buddhist schools with Mahayana affiliation.

- ^ Of special interest is the 2011 Thai translation of the six different editions of the Chinese version of the Heart Sutra under the auspices of Phra Visapathanee Maneepaket 'The Chinese-Thai Mahāyāna Sūtra Translation Project in Honour of His Majesty the King'; an example of the position of the Heart Sutra and Mahayana Buddhism in Theravadan countries.

- ^ He and Xu:

On page 12 "Based on this investigation, this study discovers ... the 661 CE Heart Sutra located in Fangshan Stone Sutra is probably the earliest extant "Heart Sutra"; [another possibility for the earliest Heart Sutra,] the Shaolin Monastery Heart Sutra commissioned by Zhang Ai on the 8th lunar month of 649 CE [Xuanzang's translated the Heart Sutra on the 24th day of the 5th lunar month in 649 CE][15]:21mentioned by Liu Xihai in his unpublished hand written draft entitled "Record of Engraved Stele's Surnames and Names", [regarding this stone stele, it] has so far not been located and neither has any ink impressions of the stele. It's possible that Liu made a regnal era transcription error. (He and Xu mention there was a Zhang Ai who is mentioned in another stone stele commissioned in the early 8th century and therefore the possibility Liu made a regnal era transcription error;however He and Xu also stated the existence of the 8th century stele does not preclude the possibility that there could have been two different persons named Zhang Ai.)[15]:22–23 The Shaolin Monastery Heart Sutra stele awaits further investigation."[15]:28

On page 17 "The 661 CE and the 669 CE Heart Sutra located in Fangshan Stone Sutra mentioned that "Tripitaka Master Xuanzang translated it by imperial decree" (Xian's Beilin Museum's 672 CE Heart Sutra mentioned that "Śramaṇa Xuanzang translated it by imperial decree"..." - ^ Harada's cross-philological study is based on Chinese, Sanskrit and Tibetan texts.

- ^ Choo :

* On p 146–147 [quote from Woncheuk's Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sutra Commentary] "A version [of the Heart Sūtra (in Chinese)] states that “[The Bodhisattva] illuminatingly sees that the five aggregates, etc., are all empty.” Although there are two different versions [(in Chinese)], the latter [that is, the new version] is the correct one because the word “etc.” is found in the original Sanskrit scripture. [The meaning of] “etc.” described in the latter [version] should be understood based on [the doctrine of Dharmapāla]." - ^ Some Sanskrit Titles of the Heart Sutra from 8th–13th centuries CE

- āryabhagavatīprajñāpāramitāhṛdayaṃ (Holy Mother of all Buddhas Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom) Sanskrit title of Tibetan translation by unknown translator.

- bhagavatīprajñāpāramitāhṛdayaṃ (Mother of all Buddhas Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom) Sanskrit title of Tibetan translation by Vimalamitra who studied in Bodhgayā (today's Bihar State in North Eastern India) in the 8th century CE.

- āryabhagavatīprajñāpāramitā (Holy Mother of all Buddhas Perfection of Wisdom) Sanskrit title of Chinese translation by Dānapāla who studied in Oddiyana (today's Swat Valley Pakistan near Afghanistan-Pakistan border) in the 11th century CE.

- āryabhagavatīprajñāpāramitā (Holy Mother of all Buddhas Perfection of Wisdom) Sanskrit title of Chinese translation by Dharmalāḍana in the 13th century CE.[26]:29

- ^ Sonam Gyaltsen Gonta : 直譯經題的「bCom ldan ’das ma」就是「佛母」之意。接下來我們要討論的是「shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa'i」(般若波羅蜜多)。....講述這個般若波羅蜜的經典有《十萬頌般若》、《二萬五千頌般若》、《八千頌般若》...而將《大般若經》的龐大內容、深遠幽玄本質,不但毫無損傷反而將其濃縮在極精簡扼要的經文中,除了《般若心經》之外沒有能出其右的了,因此經題中有「精髓」兩字。(transl: Directly translating the title "bCom ldan 'das ma" - it has the meaning of "Mother of all Buddhas". Now we will discuss the meaning of "shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa'i" (prajñāpāramitā).... Describing the prajñāpāramitā, we have the Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra [Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra in 100,000 verses], the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra [Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra in 25,000 verses], Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra [Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra in 8,000 verses]...there are no works besides the Heart Sutra that even comes close to condensing the vast contents of the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra's [(the name of a Chinese compilation of complete prajñāpāramitā sutras having 16 sections within it and including the 3 aforementioned sutras)] far-reaching profundity into an extremely concise form without any lost in meaning and therefore the title has the two words ["snying po"] meaning "essence" [or "heart"]

- ^ Powers xix: [Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva's association with the Prajñāpāramitā genre can also be seen in the Saṁdhinirmocana Mahāyāna Sūtra, where Avalokiteśvara asks Buddha about the Ten Bodhisattva Stages and ] Each stage represents a decisive advance in understanding and spiritual attainment. The questioner here is Avalokiteśvara, the embodiment of compassion. The main meditative practice is the six perfections - generosity, ethics, patience, effort, concentration and wisdom - the essence of the Bodhisattva's training. (for details pls see pp 249-271)

- ^ There were two waves of transliterations. One was from China which later mainly spread to Korea, Vietnam and Japan. Another was from Tibet. Classical transliterations of the mantra include:

- simplified Chinese: 揭谛揭谛,波罗揭谛,波罗僧揭谛,菩提萨婆诃; traditional Chinese: 揭諦揭諦,波羅揭諦,波羅僧揭諦,菩提薩婆訶; pinyin: Jiēdì jiēdì, bōluójiēdì, bōluósēngjiēdì, pútí sàpóhē

- Vietnamese: Yết đế, yết đế, Ba la yết đế, Ba la tăng yết đế, Bồ đề tát bà ha

- Japanese: 羯諦羯諦、波羅羯諦、波羅僧羯諦、菩提薩婆訶; Japanese pronunciation: Gyatei gyatei haragyatei harasōgyatei boji sowaka

- Korean: 아제 아제 바라아제 바라승아제 모지 사바하; romaja: Aje aje bara-aje baraseung-aje moji sabaha

- Tibetan: ག༌ཏེ༌ག༌ཏེ༌པཱ༌ར༌ག༌ཏེ༌པཱ༌ར༌སཾ༌ག༌ཏེ༌བོ༌དྷི༌སྭཱ༌ཧཱ། (gate gate paragate parasangate bodi soha)

- ^ Nguyen

*gives the Vietnamese title of Phap Loa's commentary as 'Bát Nhã Tâm Kinh Khoa Sớ' which is the Vietnamese reading of the Sino-Viet title (also given) '般若心經科疏'. (The English translation is 'Commentary on the Prajñāhṛdaya Sutra'.)

Thich

*gives Pháp Loa's name in Chinese as 法螺 - ^ For those interested, the Chinese language titles are as follows:

- 《般若波羅蜜多心經幽贊》 ( 2 卷)[1]

- 《般若波羅蜜多心經贊》 ( 1 卷) [2]

- 《般若波羅蜜多略疏》 ( 1 卷) [3]

- 《般若心經疏》( 1 卷) [4]

- 《般若心經疏》( 1 卷) [5]

- 《般若心経秘鍵》( 1 卷) [6]

- 《心經直說》( 1 卷) [7]

- 《心經說》( 29 卷) (參11 卷) [8]

- 《心經釋要》( 1 卷) [9]

- 《般若心経毒語》[10]

- ^ For those interested, the CJKV names are as follows:

- 窺基

- 원측; 圓測

- 法藏

- 靖邁

- 慧淨

- 空海

- 憨山德清

- 紫柏真可

- 蕅益智旭

- 白隠慧鶴

- ^ For those interested, the Sanskrit titles are as follows:

1.Āryaprajñāpāramitāhṛdayaṭīkā

2.Prajñāhṛdayaṭīkā

3.Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayamaṭīkā

4.Mantravivṛtaprajñāhṛdayavṛtti

5.Āryaprajñāpāramitāhṛdayavyākhyā

6.Āryaprajñāpāramitāhṛdayaṭīkā

7.Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayārthamaparijñāna

8.Bhagavatīprajñāpāramitāhṛdayathapradīpanāmaṭīkā

9.Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayaṭīkā - ^ Lopez Jr.:

[Vairocana, a disciple of Srisimha was] ordained by Śāntarakṣita at bSam yas c. 779 CE. - ^ Zhou 1959 :

(not the famous Āryadeva from the 3rd century CE but another monk with a similar name from c. 10th century)

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Pine 2004

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Lusthaus 2003

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Lopez Jr. 1996

- ^ Jump up to:a b Harada 2010

- ^ Tai 2005

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sonam Gyaltsen Gonta 2009

- ^ प्रज्ञापारमिताहृदयसूत्र (मिलन शाक्य) [Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (tr. from Sanskrit to Nepal Bhasa)] (in Nepali). Translated by Shākya, Milan. 2003.

- ^ Ledderose, Lothar (2006). "Changing the Audience: A Pivotal Period in the Great Sutra Carving Project". In Lagerway, John (ed.). Religion and Chinese Society Ancient and Medieval China. 1. The Chinese University of Hong Kong and École française d'Extrême-Orient. p. 395.

- ^ Lee, Sonya (2010). "Transmitting Buddhism to A Future Age: The Leiyin Cave at Fangshan and Cave-Temples with Stone Scriptures in Sixth-Century China". Archives of Asian Art. 60.

- ^ 佛經藏經目錄數位資料庫-般若波羅蜜多心經 [Digital Database of Buddhist Tripitaka Catalogues-Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayasūtra]. CBETA (in Chinese).

【房山石經】No.28《般若波羅蜜多心經》三藏法師玄奘奉詔譯 冊數:2 / 頁數:1 / 卷數:1 / 刻經年代:顯慶六年[公元661年] / 瀏覽:目錄圖檔 [tr to English : Fangshan Stone Sutra No. 28 "Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Sutra" Tripitaka Master Xuanzang translated by imperial decree Volume 2, Page 1 , Scroll 1 , Engraved 661 CE...]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d He 2017

- ^ Jump up to:a b Nattier 1992

- ^ Attwood, Jayarava. "The History of the Heart Sutra as a Palimpsest", 157.

- ^ Attwood, Jayarava. "'Epithets of the Mantra' in the Heart Sutra", 31, 44.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Choo 2006

- ^ Attwood, Jayarava. "The History of the Heart Sutra as a Palimpsest", 174-178.

- ^ Attwood, Jayarava. "'Epithets of the Mantra' in the Heart Sutra", 43-44.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Zhou 1959

- ^ Powers, 1995

- ^ Keenan 2000

- ^ "Prajñaparamita mantra: Gate gate paragate parasaṃgate bodhi svaha". wildmind.org. Retrieved 2018-08-10.

Gate gate pāragate pārasamgate bodhi svāhā... The words here do have a literal meaning: “Gone, gone, gone beyond, gone utterly beyond, Enlightenment hail!

- ^ Shih and Lusthaus, 2006

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Dreitlein 2011

- ^ Nguyen 2008

- ^ If listing starts with 'T' and followed by number then it can be found in the Taisho Tripitaka; if listing starts with 'M' and followed by number then it can be found in the Manjizoku Tripitaka; If listing starts with 'B' and followed by number then it can be found in the Supplement to the Great Tripitaka

- ^ Minoru 1978 (cf references)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Foguangshan 1989

- ^ Luk 1970

- ^ von Staël-Holstein, Baron A. (1999). Silk, Jonathan A. (ed.). "On a Peking Edition of the Tibetan Kanjur Which Seems to be Unknown in the West". Journal of International Association of Buddhist Studies. 22 (1): 216.

cf footnote (b)-refers to Ōtani University (大谷大学) copy (ed.) of Peking Tripitaka which according to Sakurabe Bunkyō, was printed in China 1717/1720.

- ^ 藏文大藏經 [The Tibetan Tripitaka]. 全球龍藏館 [Universal Sutra of Tibetan Dragon]. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

北京版。又名嵩祝寺版。清康熙二十二年(1683)據西藏霞盧寺寫本在北京嵩祝寺刊刻,先刻了甘珠爾。至雍正二年(1724)續刻了丹珠爾。早期印本大部為硃刷,也稱赤字版。版片毀於光緒二十六年庚子之役。 (tr. to English: Beijing (Peking Tripitaka) ed., is also known as Songzhu Temple edition. In 1683, Beijing's Songzhu Temple first carved woodblocks for the Kangyur based on manuscripts from Tibet's Xialu Temple (Shigatse's Shalu Monastery). In 1724, they continued with the carving of woodblocks for the Tengyur. The early impressions were in large part, printed in vermilion ink and therefore are also known as the 'Vermilion Text Edition.' The woodblocks were destroyed in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion.)

- ^ If listing starts with 'M' and followed by number then it can be found in the Manjizoku Tripitaka

- ^ Fukuda 1964

- ^ Jump up to:a b Liao 1997

- ^ Beal (1865: 25–28)

- ^ Müller (1881)

- ^ DharmaSound (in web.archive.org): Sūtra do Coração in various languages (mp3)

- ^ 心经试听下载, 佛教音乐专辑心经 - 一听音乐网. lting.com (in Chinese).

- ^ 佛學多媒體資料庫. Buda.idv.tw. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ 經典讀誦心經香港群星合唱迴向1999年, 台灣921大地震. Youtube.com. 2012-08-10. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ Faye Wong sings at Buddhist Event

- ^ 《大地震》片尾曲引爭議 王菲尚雯婕誰是主題曲. Sina Daily News(in Chinese). 2010-07-28.

- ^ 般若波罗密多心经. Archived from the original on 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2015-05-17.

- ^ 黄晓明《大唐玄奘》MV曝光 王菲版《心经》致敬 (in Chinese). People.com.cn Entertainment. 2016-04-21.

- ^ "Lou Harrison obituary" (PDF). Esperanto magazine. 2003. Retrieved December 15, 2014. (text in Esperanto)

- ^ Syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism by VOCALOID, 2015-11-12, retrieved 2018-07-19

- ^ "Aya Dances 3 Earthly Desires in Gate of Living-Ringo Sheena". en.cabin.tokyo. 2019-05-22. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ^ Yu, 6

- ^ Ehrlich, Dimitri (2004). "Doors Without Walls". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ Chen, Xiaolin (陳小琳); Chen, Tong (陳彤). Episode 1. 西遊記 (2011年電視劇) (in Chinese).

This prelude song was not used in the television series shown in Hong Kong and Taiwan. The mantra as sung here is Tadyatha Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate Bodhi Svaha.

- ^ 不肯去观音 [Avalokitesvara] (in Chinese). 2013.

In the first five minutes, there are two chantings of the Heart Sutra. The first time, Buddhist monks chant in Chinese blessing the making of a statue of Avalokitesvara bodhisattva for the benefit of a disabled prince. (The prince is later healed and becomes the future Emperor Xuānzong.) The second time, we hear the singing of the mantra of the Sanskrit Heart Sutra in the background. Shortly after the Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī is chanted. The Chinese version of the Eleven-Faced Guanyin Heart Dharani is also chanted. Egaku chants the Heart Sutra in Japanese in a later segment. The film is a loose retelling of the origin of Mount Putuo.

- ^ ボクは坊さん。 [I Am a Monk] (in Japanese). 2015.

- ^ McCreary, Bear (June 15, 2019). "Godzilla King of the Monsters". Bear's Blog. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ …ist denen, in welchen der Wille sich gewendet und verneint hat, diese unsere so sehr reale Welt mit allen ihren Sonnen und Milchstraßen—Nichts.

- ^ Dieses ist eben auch das Pradschna–Paramita der Buddhaisten, das 'Jenseit aller Erkenntniß,' d.h. der Punkt, wo Subjekt und Objekt nicht mehr sind. (Isaak Jakob Schmidt, "Über das Mahâjâna und Pradschnâ-Pâramita der Bauddhen". In: Mémoires de l'Académie impériale des sciences de St. Pétersbourg, VI, 4, 1836, 145–149;].)

Sources[edit]

- Beal, Samuel. (1865) The Paramita-hridaya Sutra. Or. The Great Paramita Heart Sutra. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No.2 Dec 1865, 25-28

- BTTS, (Buddhist Text Translation Society) (2002). Daily Recitation Handbook : Sagely City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. ISBN 0-88139-857-8.

- Brunnhölzl, Karl (September 29, 2017), The Heart Sutra Will Change You Forever, Lion's Roar, retrieved August 24, 2019

- Buswell Jr., Robert E. (2003), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, MacMillan Reference Books, ISBN 0-02-865718-7

- Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Lopez Jr., Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3

- Choo, B. Hyun (February 2006), "An English Translation of the Banya paramilda simgyeong chan: Wonch'uk's Commentary on the Heart Sūtra (Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya-sūtra)", International Journal of Buddhist Thought & Culture., 6: 121–205.

- Conze, Edward (1948), "Text, Sources, and Bibliography of the Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 80 (1): 33–51, doi:10.1017/S0035869X00101686, JSTOR 25222220

- Conze, Edward (1967), "The Prajñāpāramitā-Hṛdaya Sūtra", Thirty Years of Buddhist Studies: Selected Essays, Bruno Cassirer, pp. 147–167

- Conze, Edward (1975), Buddhist Wisdom Books: Containing the "Diamond Sutra" and the "Heart Sutra", Thorsons, ISBN 0-04-294090-7

- Conze, Edward (2000), Prajnaparamita Literature, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, ISBN 81-215-0992-0 (originally published 1960 by Mouton & Co.)

- Conze, Edward (2003), The Short Prajñāpāramitā Texts, Buddhist Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0946672288

- Dreitlein, Thomas Eijō (2011). An Annotated Translation of Kūkai's Secret Key to the Heart Sūtra (PDF). 24. 高野山大学密教文化研究所紀要(Bulletin of the Research Institute of Esoteric Buddhist Culture). pp. 1–48(L).

- e-Museum, National Treasures & Important Cultural Properties of National Museums, Japan (2018), "Sanskrit Version of Heart Sutra and Vijaya Dharani", e-Museum

- Foguangshan Foundation for Buddhist Culture and Education (佛光山文教基金會) (1989). 佛光山大詞典 [Foguangshan Dictionary of Buddhism] (in Chinese). ISBN 9789574571956.

- Fukuda, Ryosei (福田亮成) (1964). 般若理趣經・智友Jñānamitra釋における一・二の問題 [A Few Problems with Jñānamitra's Commentary on the Adhyardhaśatikā prajñāpāramitā]. Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies (Indogaku Bukkyogaku Kenkyu) (in Japanese). Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. 12 (23): 144–145. doi:10.4259/ibk.12.144.

- Fukui, Fumimasa (福井文雅) (1987). 般若心経の歴史的研究 [Study of the History of the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra] (in Japanese, Chinese, and English). Tokyo: Shunjūsha (春秋社). ISBN 978-4393111284.

- Hakeda, Y.S. (1972). Kūkai, Major works: Translated and with an account of his life and a study of his thought. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231059336.

esp. pp 262–276 which has the English translation of Secret Key to the Heart Sutra

- Harada, Waso (原田和宗) (2002). 梵文『小本・般若心経』和訳 [An Annotated Translation of The Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya]. 密教文化 (in Japanese). Association of Esoteric Buddhist Studies. 2002 (209): L17–L62. doi:10.11168/jeb1947.2002.209_L17.

- Harada, Waso (原田和宗) (2010). 「般若心経」の成立史論」 [History of the Establishment of Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayasūtram] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Daizō-shuppan 大蔵出版. ISBN 9784804305776.

- He, Ming (贺铭); Xu, Xiao yu (续小玉) (2017). "2" 早期《心经》的版本 [Early Editions of the Heart Sutra]. In Wang, Meng nan (王梦楠); Fangshan Stone Sutra Museum (房山石经博物馆); Fangshan Stone Sutra and Yunju Temple Culture Research Center (房山石经与云居寺文化研究中心) (eds.). 石经研究 第一辑 [Research on Stone Sutras Part I] (in Chinese). 1. Beijing Yanshan Press. pp. 12–28. ISBN 9787540243944.

- Ishii, Kōsei (石井 公成) (2015). 『般若心経』をめぐる諸問題 : ジャン・ナティエ氏の玄奘創作説を疑う [Issues Surrounding the Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya: Doubts Concerning Jan Nattier’s Theory of a Composition by Xuanzang]. 64. Translated by Kotyk, Jeffrey. 印度學佛教學研究. pp. 499–492.

- The Scripture on the Explication of the Underlying Meaning [Saṁdhinirmocana Sūtra]. Translated by Keenan, John P.; Shi, Xuanzang [from Sanskrit to Chinese]. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. 2006. ISBN 978-1886439108.

Translated from Chinese

- Kelsang Gyatso, Geshe (2001). Heart of Wisdom: An Explanation of the Heart Sutra, Tharpa Publications, (4th. ed.). ISBN 978-0-948006-77-7

- Liao, Bensheng (廖本聖) (1997), 蓮花戒《般若波羅蜜多心經釋》之譯注研究 (廖本聖著) [Research on the Translation of Kamalaśīla’s Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayamaṭīkā], Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal, 10 (in Chinese): 83–123

- Lopez Jr., Donald S. (1988), The Heart Sutra Explained: Indian and Tibetan Commentaries, State Univ of New York Pr., ISBN 0-88706-589-9

- Lopez Jr., Donald S. (1996), Elaborations on Emptiness: Uses of the Heart Sūtra, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691001883

- Luk, Charles (1970), Ch'an and Zen Teaching (Series I), Berkeley: Shambala, pp. 211–224, ISBN 0877730091 (cf pp 211–224 for tr. of Hanshan Deqing's Straight Talk on the Heart Sutra (Straightforward Explanation of the Heart Sutra))

- Lusthaus, Dan (2003). The Heart Sūtra in Chinese Yogācāra: Some Comparative Comments on the Heart Sūtra Commentaries of Wŏnch’ŭk and K’uei-chi. International Journal of Buddhist Thought & Culture 3, 59–103.

- McRae, John (2004), "Heart Sutra", in Buswell Jr., Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, MacMillan

- Minoru Kiyota (1978). Mahayana Buddhist Meditation: Theory and Practice Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. (esp. Cook, Francis H. ‘Fa-tsang’s Brief Commentary on the Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya-sūtra.’ pp. 167–206.) ISBN 978-8120807600

- Müller, Max (1881). ‘The Ancient Palm Leaves containing the Prajñāpāramitā-Hṛidaya Sūtra and Uṣniṣa-vijaya-Dhāraṇi.’ in Buddhist Texts from Japan (Vol 1.iii). Oxford Univers* ity Press. Online

- Nattier, Jan (1992), "The Heart Sūtra: A Chinese Apocryphal Text?", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 15 (2): 153–223

- Nguyen, Tai Thu (2008). The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. Institute of Philosophy, Vietnamese Academy of Social Sciences-The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. ISBN 978-1565180987.

- Pine, Red (2004), The Heart Sutra: The Womb of the Buddhas, Shoemaker 7 Hoard, ISBN 1-59376-009-4

- Wisdom of Buddha The Saṁdhinirmocana Mahāyāna Sūtra. Translated by Powers, John. Dharma Publishing. 1995. ISBN 978-0898002461.

Translated from Tibetan

- Rinpoche, Tai Situ (2005), Ground, Path and Fruition, Zhyisil Chokyi Ghatsal Chatitable Trust, ISBN 978-1877294358

- Shih, Heng-Ching & Lusthaus, Dan (2006). A Comprehensive Commentary on the Heart Sutra (Prajnaparamita-hyrdaya-sutra). Numata Center for Buddhist Translation & Research. ISBN 978-1886439115

- Siu, Sai yau (蕭世友) (2017). 略本《般若波羅蜜多心經》重探:漢譯,譯史及文本類型 [Reinvestigation into the Shorter Heart Sūtra: Chinese Translation, History, and Text Type] (in Chinese). Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Sonam Gyaltsen Gonta, Geshe (索南格西); Shithar, Kunchok(貢卻斯塔); Saito, Yasutaka(齋藤保高) (2009). チベットの般若心経 西藏的般若心經 [The Tibetan Heart Sutra] (in Chinese). Translated by 凃, 玉盞 (Tu Yuzhan). (Original language in Japanese). Taipei: Shangzhou Press (商周出版). ISBN 9789866369650.

- Storch, Tanya (2014). The History of Chinese Buddhist Bibliography: Censorship and Transformation of the Tripitaka. Amherst, New York: Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1604978773.

- Tanahashi, Kazuki (2014), The Heart Sutra: A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism', Shambala Publications, ISBN 978-1611803129

- Thích, Thiện Ân (1979). Buddhism and Zen in Vietnam in relation to the development of Buddhism in Asia. Charles E.Tuttle & Co. ISBN 978-0804811446.

- Waddell, Norman (1996). Zen Words for the Heart: Hakuin's Commentary on the Heart Sutra. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala. ISBN 978-1-57062-165-9.

- "Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra]" (PDF). Translated by Yifa, Venerable; Owens, M.C.; Romaskiewicz, P.M. Buddha's Light Publishing. 2005.

- Yu, Anthony C. (1980). The Journey to the West. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-97150-6. First published 1977.

- Zhou, Zhi'an (周止菴) (1959). 般若波羅蜜多心經詮注 [Commentaries on the Prañāpāramitāhṛdaya Sutra] (in Chinese). Taichung: The Regent Store.

Further reading[edit]

- Conze, Edward (translator) (1984). Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines & Its Verse Summary. Grey Fox Press. ISBN 978-0-87704-049-1.

- Fox, Douglass (1985). The Heart of Buddhist Wisdom: A Translation of the Heart Sutra With Historical Introduction and Commentary. Lewiston/Queenston Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-053-1.

- Gyatso, Tenzin, The Fourteenth Dalai Lama (2002). Jinpa, Thumpten (ed.). Essence of the Heart Sutra: The Dalai Lama's Heart of Wisdom Teachings. English translation by Geshe Thupten Jinpa. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-318-4.

- Hasegawa, Seikan (1975). The Cave of Poison Grass: Essays on the Hannya Sutra. Arlington, Virginia: Great Ocean Publishers. ISBN 0-915556-00-6.

- McRae, John R. (1988). "Ch'an Commentaries on the Heart Sutra". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 11 (2): 87–115.

- McLeod, Ken (2007). An Arrow to the Heart. Victoria, BC, Canada: Trafford. ISBN 978-1-4251-3377-1. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27.

- Thich, Nhat Hanh (1988). The Heart of Understanding. Berkeley, California: Parallax Press. ISBN 978-0-938077-11-4.

- Rinchen, Sonam. (2003) Heart Sutra: An Oral Commentary Snow Lion Publications

- Shih, Heng-ching, trans. (2001). A Comprehensive Commentary on the Heart Sutra (transl. from the Chinese of K'uei-chi). Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1-886439-11-7.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Documentary[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Translations[edit]