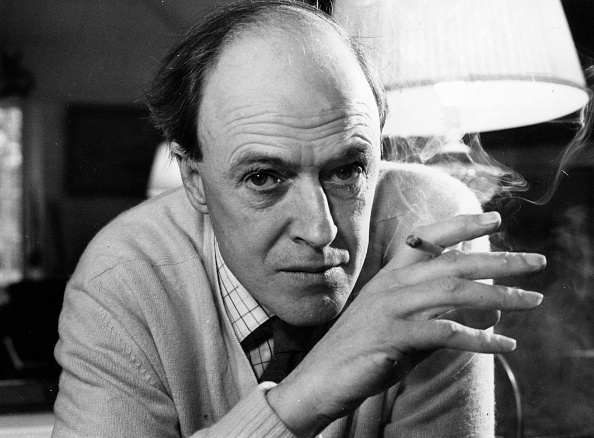

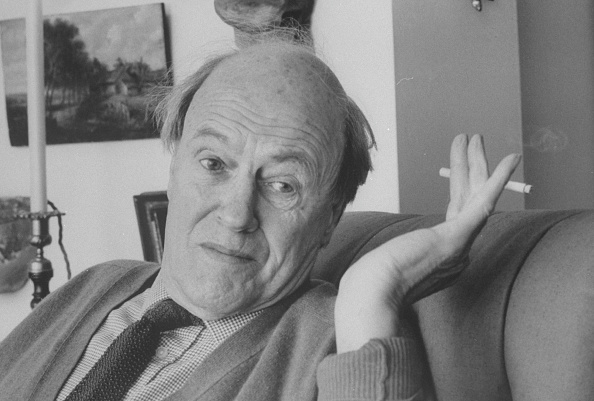

What to Know About Children's Author Roald Dahl's Controversial Legacy

To many, Roald Dahl is the genius behind some of the world’s most beloved children’s books, including Matilda, James and the Giant Peach and The BFG. But since his death in 1990, a dark side of the author’s personal life has raised questions about his life’s work and legacy.

Dahl’s collection of fantastical children’s stories have brought joy to millions of readers for decades, and continue to inspire new adaptations and reboots. In January, Warner Bros. announced that it had set a release date of March 17, 2023 for Wonka, a movie prequel to Dahl’s 1964 book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory that will center on “a young Willy Wonka and his adventures prior to opening the world’s most famous chocolate factory.”

Netflix, which reportedly paid the Roald Dahl Story Company at least $1 billion in 2018 for the rights to 16 of the author’s works, also has two animated series based on the world and characters of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in development. Taika Waititi (Thor: Ragnarok, Jojo Rabbit) is writing, directing and executive producing both shows. Of course, this isn’t the first time one of Dahl’s books has been adapted for the screen. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has twice previously been made into a movie—once in 1971, with Gene Wilder starring as the titular candy man in the much-beloved Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, and again in 2005, with Johnny Depp taking up the Wonka mantle for Tim Burton’s take on the classic. Big-screen versions of The Witches (1990 and 2020), James and the Giant Peach (1996), Matilda (1996), Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) and The BFG (2016) have also found success.

Despite Dahl publicly admitting he was anti-Semitic in an interview shortly before his death at age 74, in addition to a number of reports of his alleged misogyny and racism, for a long time it seemed that the immense popularity of his books, and their accompanying adaptations, overshadowed concerns regarding his reputed prejudices.

In recent years, some have sought to shine a brighter light on the troubling nature of Dahl’s personal views. In 2018, The Guardian reported that the British Royal Mint had rejected a proposal to mark the 100th anniversary of Dahl’s birth with a commemorative coin due to the fact that he was “associated with anti-Semitism and not regarded as an author of the highest reputation.” In response to the Royal Mint’s decision, Amanda Bowman, vice president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, also spoke out against Dahl. “The Royal Mint was absolutely correct to reject the idea of a commemorative coin for Roald Dahl,” she said. “Many of his utterances were unambiguously anti-Semitic. He may have been a great children’s writer but he was also a racist and this should be remembered.”

In December 2020, it came to light that the Dahl family and Roald Dahl Story Company, in what some saw as a preemptive move to deflect criticism of forthcoming projects, had issued an apology for Dahl’s history of anti-Semitism on the official Dahl website. It’s unclear exactly when the statement first appeared on the site.

“The Dahl family and the Roald Dahl Story Company deeply apologize for the lasting and understandable hurt caused by some of Roald Dahl’s statements,” it reads. “Those prejudiced remarks are incomprehensible to us and stand in marked contrast to the man we knew and to the values at the heart of Roald Dahl’s stories, which have positively impacted young people for generations. We hope that, just as he did at his best, at his absolute worst, Roald Dahl can help remind us of the lasting impact of words.”

In a statement obtained by TIME, the Roald Dahl Story Company also noted that the company and Dahl’s family “have apologized unreservedly for the hurt and suffering caused by Roald Dahl’s anti-Semitic comments. Those prejudiced statements are in marked contrast to the values of kindness and inclusivity at the heart of Roald Dahl’s stories.”

Due in part to the controversy surrounding transphobic comments made by Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling over the past year, news of new Dahl projects has come amid a period of increased scrutiny of writers’ personal views and whether those views can be separated from their work. Dr. Seuss Enterprises recently announced that it would cease publication of six of the author’s books that have racist and insensitive imagery, a move which some critics, including Donald Trump, Jr., chalked up to “cancel culture.” But as Abraham Foxman, the national director of the Anti-Defamation League at the time, wrote in a 1990 letter to The New York Times following Dahl’s death, “Talent is no guarantee of wisdom. Praise for Mr. Dahl as a writer must not obscure the fact that he was also a bigot.”

Here’s what you need to know about the author’s history of prejudice and how it’s impacting his legacy today.

Dahl’s personal life and early career

In the 1993 book Roald Dahl: A Biography, author Jeremy Treglown wrote that Dahl was a man of contradictions: “He was famously a war hero, a connoisseur, a philanthropist, a devoted family man who had to confront an appalling succession of tragedies. He was also, as will be seen, a fantasist, an anti-Semite, a bully and a self-publicizing troublemaker.”

A native of Wales, Dahl lived in Africa for a year after taking a position with Shell Oil in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now in Tanzania), following his graduation from Repton, a British boarding school, in 1934. In 1939, following the outbreak of World War II, he enlisted in the Royal Air Force and served as a fighter pilot before suffering severe injuries to his head, nose and back in a plane crash in the Libyan desert. Dahl was eventually sent to Washington, D.C., to join the British Embassy as an assistant air attaché, and it was there that he began his writing career, publishing a short story in the Saturday Evening Post.

In July 1953, Dahl married Hollywood actor Patricia Neal, who later nicknamed him “Roald the Rotten” because of his alleged mistreatment of her. The couple settled in Great Missenden, England, and had five children together. But in the midst of his writing career taking off, Dahl faced a series of family tragedies. Ahead of the 1961 publication of James and the Giant Peach, Dahl’s 4-month-old son Theo suffered a severe brain injury when his pram was hit by a taxi in New York City. This was followed by the death of his eldest daughter, Olivia, of measles encephalitis at the age of 7 in November 1962. Neal then suffered a series of strokes in February 1965 from which she never fully recovered.

Dahl and Neal divorced in 1983, and later that year he married set designer Felicity Crosland, with whom he’d allegedly had an 11-year affair. Dahl’s later years were arguably the most successful of his career, but also the period that has fueled the most controversy.

What did Roald Dahl say that was anti-Semitic?

During his lifetime, Dahl made openly anti-Semitic remarks on a number of occasions.

In a review of a book about the Lebanon War that appeared in the August 1983 edition of the British periodical Literary Review, Dahl wrote, in reference to Jewish people, “Never before in the history of man has a race of people switched so rapidly from being much-pitied victims to barbarous murderers.”

He also made reference to “those powerful American Jewish bankers” and asserted that the United States government was “utterly dominated by the great Jewish financial institutions over there.”

Later that same year, he doubled down on his statements in an interview with the British magazine New Statesman. “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews,” he said. “I mean, there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere; even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”

A few months before his death in 1990, Dahl stated outright that he was anti-Semitic in an interview with The Independent.

After claiming that Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon was “hushed up in the newspapers because they are primarily Jewish-owned,” he went on to say, “I’m certainly anti-Israeli and I’ve become anti-Semitic in as much as that you get a Jewish person in another country like England strongly supporting Zionism. I think they should see both sides. It’s the same old thing: we all know about Jews and the rest of it. There aren’t any non-Jewish publishers anywhere, they control the media—jolly clever thing to do—that’s why the president of the United States has to sell all this stuff to Israel.”

Dahl’s children’s books aren’t considered notably anti-Semitic. However, his publishers—especially longtime editor Stephen Roxburgh—are credited with cutting racist and misogynistic content from some of his most famous stories, including The Witches, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and The BFG.

In a 2013 reminiscence on working with Dahl on The Witches, Roxburgh wrote, “I was concerned about the portrayal of women, but Roald wasn’t.” Roxburgh recalls Dahl telling him: “I don’t agree with you about women coming in for a lot of stick all the way through. The nicest person in the whole thing is a woman [the grandmother] so I have not changed anything here.”

The 1983 book has been banned by some U.K. libraries for its perceived negative portrayal of women, and also appears on the American Library Association’s list of the 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990 to 1999.

As for Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Dahl’s original portrayal of the Oompa-Loompas, depicting them as African pygmies that Willy Wonka shipped to England “in large packing cases with holes in them,” has also been duly criticized for perpetuating racist ideologies. “In the 1964 book, Wonka explains that he found the Oompa-Loompas ‘in the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle where no white man had ever been before.’ They were near starvation, living on vile caterpillars, so Wonka smuggled them to England for their own good,” Livia Gershon wrote in December 2020 for JSTOR Daily. “The wildly colonialist stereotyping apparently received little pushback until 1971, when plans were announced for a U.S. movie version of the book.”

Even after the NAACP began protesting this depiction of the Oompa-Loompas, Dahl was apparently reluctant to rewrite the characters. But he did eventually revise the book, reimagining the Oompa-Loompas as “long-haired, rosy-cheeked, and white, hailing from the island of Loompaland.” In the movie Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, the Oompa-Loompas have orange skin.

Dahl’s widow, Felicity Dahl, claimed in a 2017 interview with BBC Radio 4 Today alongside Dahl biographer Donald Sturrock that the titular character in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was initially Black, but Dahl’s agent insisted Charlie Bucket be portrayed as white because of concerns about having a “Black hero.”

Even so, previous criticisms reportedly also did not temper a racist description of the Big Friendly Giant in an early draft of The BFG, which was ultimately changed before the book was published in 1982. “[Dahl’s] first draft of The BFG, the friendly giant at the center of that book emerged as the very worst imitation of a Zip Coon figure, a black, flat-nosed, giant with ‘thick rubbery lips . . . like two gigantic purple frankfurters lying on top of the other,'” wrote historian Donald Yacovone, an associate at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, in 2018. “For once, an editor spoke up.” Yacovone said Roxbourgh, who later edited The Witches and Matilda, “properly denounced Dahl’s characterization as a ‘derisive stereotype.’ Dahl conceded the point, responding: ‘the negro lips thing is taken care of.'”

Response to the Dahl family apology

In the wake of the Dahl family’s apology, the Campaign Against Antisemitism said in a statement that while it was encouraging for Dahl’s prejudices to be acknowledged by “those who profit from his creative works,” the acknowledgment was long overdue.

“The admission that the famous author’s anti-Semitic views are ‘incomprehensible’ is right. For his family and estate to have waited thirty years to make an apology, apparently until lucrative deals were signed with Hollywood, is disappointing and sadly rather more comprehensible,” the statement read. “It is a shame that the estate has seen fit merely to apologize for Dahl’s anti-Semitism rather than to use its substantial means to do anything about it. The apology should have come much sooner and been published less obscurely.”

The family offered a bit more context on their original apology in a December statement to The Sunday Times. “Apologizing for the words of a much-loved grandparent is a challenging thing to do, but made more difficult when the words are so hurtful to an entire community. We loved Roald, but we passionately disagree with his anti-Semitic comments,” they said. “This is why we chose to apologize on our website, an apology easily found on Google…These comments do not reflect what we see in his work—a desire for the acceptance of everyone equally—and were entirely unacceptable. We are truly sorry.”

Suggesting that the “teaching of Dahl’s books should also be used as an opportunity for young people to learn about his intolerant views,” Marie van der Zyl, president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, also spoke out against the timing of the family’s statement. “This apology should have happened long ago—and it is of concern that it has happened so quietly now,” she said in a statement. “Roald Dahl’s abhorrent anti-Semitic prejudices were no secret and have tarnished his legacy.”