Taoist philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

Taoist philosophy (Chinese: 道學; pinyin: Dàoxué; lit. 'study of the Tao') also known as Taology refers to the various philosophical currents of Taoism, a tradition of Chinese origin which emphasizes living in harmony with the Dào (Chinese: 道; lit. 'the Way', also romanized as Tao). The Dào is a mysterious and deep principle that is the source, pattern and substance of the entire universe.[1][2]

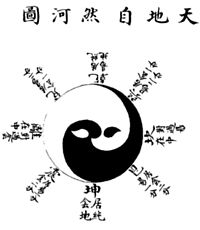

Since the initial stages of Taoist thought, there have been varying schools of Taoist philosophy and they have drawn from and interacted with other philosophical traditions such as Confucianism and Buddhism. Taoism differs from Confucianism in putting more emphasis on physical and spiritual cultivation and less emphasis on political organization. Throughout its history, Taoist philosophy has emphasised concepts like wúwéi ("effortless action"), zìrán (lit. 'self-so', "natural authenticity"), qì ("spirit"), wú ("non-being"), wújí ("non-duality"), tàijí ("polarity") and yīn-yáng (lit. 'bright and dark'), biànhuà ("transformation") and fǎn ("reversal"), and personal cultivation through meditation and other spiritual practices.

While scholars have sometimes attempted to separate "Taoist philosophy" from "Taoist religion", there was never really such a separation. Taoist texts and the literati and Taoist priests that wrote and commented on them never made the distinction between "religious" and "philosophical" ideas, particularly those related to metaphysics and ethics.[3][4]

The principal texts of this philosophical tradition are traditionally seen as the Daodejing, and the Zhuangzi, though it was only during the Han dynasty that they were grouped together under the label "Taoist" (Daojia).[4] The I Ching was also later linked to this tradition by scholars such as Wang Bi.[4] Additionally, around 1,400 distinct texts have been collected together as part of the Taoist canon (Dàozàng).

Early sources[edit]

Compared to other philosophical traditions, Taoist philosophy is quite heterogeneous. According to Russell Kirkland, "Taoists did not generally regard themselves as followers of a single religious community that shared a single set of teachings, or practices."[5] Instead of drawing on a single book or the works of one founding teacher, Taoism developed out a widely diverse set of Chinese beliefs and texts, that over time were gathered together into various synthetic traditions. These texts had some things in common, especially ideas about personal cultivation and integration with what they saw as the deep realities of life.[6]

The first group consciously identifying itself as "Taoist" (Dàojiào) appeared and began to collect texts during the fifth century CE.[7] Their collection of Taoist texts did not initially include classics typically considered to be "Taoist" like the Tao Te Ching and the Zhuangzi. Only after a later expansion of the canon did these texts become included.[8]

The legend of the "person" Laozi was developed during the Han dynasty and has no historical validity.[8] Likewise the labels Taoism and Confucianism were developed during the Han dynasty by scholars to group together various thinkers, and texts of the past and categorize them as "Taoist", even though they are quite diverse and their authors may never have known of each other.[9] Thus, while there was never a coherent "school" of "classical Taoism" during the pre-Han eras, later self-identified Taoists (c. 500 BCE) were influenced by streams of thought, practices and frameworks inherited from the period of the hundred schools of thought (6th century to 221 BCE).[10] According to Russell Kirkland, these independent influences include:[11]

- Mohism, which might have influenced the Taoist idea of "great peace" (tàipíng) seen in later works like the Taipingjing.

- Several divergent Confucian schools and their ideas of personal cultivation and Dào.

- Several Legalist theorists, such as Shen Buhai, who spoke of Dào and wúwéi, and Han Fei, whose work explicates some parts of the Daodejing.

- The School of Naturalists who produced the ideas of yīn and yáng and the “Five Phases” (wǔxíng).

- Ideas associated with official practitioners of divination and the I Ching.

- Early versions of independent texts like the Neiye, the Lüshi Chunqiu, the Zhuangzi, and the Daodejing.

Ideas in Taoist classics[edit]

The Daodejing (also known as the Laozi after its purported author, terminus ante quem 3rd-century BCE) has traditionally been seen as the central and founding Taoist text, though historically, it is only one of the many different influences on Taoist thought, and at times, a marginal one at that.[12] The Daodejing changed and developed over time, possibly from a tradition of oral sayings, and is a loose collection of aphorisms on various topics which seek to give the reader wise advice on how to live and govern, and also includes some metaphysical speculations.[13]

The Daodejing prominently refers to a subtle universal phenomenon or cosmic creative power called Dào (literally "way" or "road"), using feminine and maternal imagery to describe it.[14] Dào is the natural spontaneous way that things arise and exist, it is the "organic order" of the universe. The Daodejing distinguishes between the ‘named Dào’ and the ‘true Dào’ which cannot be named (wúmíng 無名) and cannot be captured by language.[3]

The Daodejing also mentions the concept of wúwéi (effortless action), which is illustrated with water analogies (going with the flow of the river instead of against it) and "encompasses shrewd tactics—among them “feminine wiles”— which one may utilize to achieve success".[15] Wúwéi is associated with yielding, minimal action and softness. Wúwéi is the activity of the ideal sage (shèng-rén), who spontaneously and effortlessly express dé (virtue), acting as one with the universal forces of the Dào, resembling children or un-carved wood (pu).[3]

They concentrate their internal energies, are humble, pliable, and content; and they move naturally without being restricted by the structures of society and culture.[3] The Daodejing also provides advice for rulers, such as never standing out, keeping weapons but not using them, keeping the people simple and ignorant, and working in subtle unseen ways instead of forceful ones.[3] It has generally been seen as promoting minimal government.

Like the Daodejing, the lesser known Neiye is a short wisdom sayings text. However, the Neiye focuses on Taoist cultivation (xiū, 修) of the heartmind (xīn, 心), which involves the cultivation and refinement of the three treasures: jīng (“vital essence”), qì (“spirit”), and shén (“soul”).[16] The Neiye's idea of a pervasive and unseen "spirit" called qì and its relationship to acquiring dé (virtue or inner power) was very influential for later Taoist philosophy. Similarly, important Taoist ideas such as the relationship between a person's xìng (“inner nature”, 性) and their mìng (“personal fate”, 命) can be found in another lesser known text called the Lüshi Chunqiu.[17] In these texts, as well as in the Daodejing, a person who acquires dé and has a balanced and tranquil heartmind is called a shèng-rén (“sage”).[18] According to Russell Kirkland:

Another text called the Zhuangzi is also seen as a classic of Taoism though it was also often a marginal work for Chinese Taoists.[19] It contains various ideas such as the idea that society and morality is a relative cultural construct, and that the sage is not bound by such things and lives, in a sense, beyond them.[20] The Zhuangzi's vision for becoming a sage requires one to empty oneself of conventional social values and cultural ideas and to cultivate wúwéi.[3] Some scholars see primitivist ideas in the Zhuangzi, advocating a return to simpler forms of life.[21]

According to Kirkland what these three texts have in common is the idea that "one can live one’s life wisely only if one learns how to live in accord with life’s unseen forces and subtle processes, not on the basis of society’s more prosaic concerns".[15] These subtle forces include qí, shén, and Dào.

Later Taoists incorporated concepts from the I Ching, like tiān (heaven). According to Livia Kohn, tiān is "a process, an abstract representation of the cycles and patterns of nature, a nonhuman force that interacted closely with the human world in a nonpersonal way."[22]

Han and Jin dynasties[edit]

The term Daojia (usually translated as "philosophical Taoism") was coined during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) by scholars and bibliographers to refer to a grouping of classic texts like the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi.[4] Though there were no self-named "Taoists" during the Han dynasty, ideas which were later important to "Taoists" can be seen in Han texts such as the Huainanzi and the Taipingjing. For example, according to the Taipingjing, the ideal ruler maintains an "air" (qí) of "great peace" (tàipíng) through the practice of wúwéi, meditation, longevity practices such as breath control and medicinal practices like acupuncture.[23] There are also commentaries written on the classics, the earliest commentary on the Daodejing is that of Heshang Gong (the "Riverside Master").[24]

Another influence to the development of later Taoism was Huáng-Lǎo (literally: "Yellow [Emperor] Old [Master]"), one of the most influential Chinese school of thought in the early Han dynasty (2nd-century BCE).[25] It was a syncretist philosophy which brought together texts and elements from many schools. Huang–Lao philosophy was favoured at the Western Han, before the reign of Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE) who made Confucianism the official state philosophy. These intellectual currents helped inspire several new social movements such as the Way of the Celestial Masters which would later influence Taoist thought.

The fourth century saw major developments such as the rise of new spiritual traditions like the Shangqing ("Supreme Clarity") and Lingbao ("Numinous Treasure") with new scriptures and practices such as alchemy and visualization meditations as a way of moral and spiritual refinement.[26] It was the Lingbao school who also developed the ideas of a great cosmic deity as a personification of the Tao and a heavenly order with Mahayana Buddhist influences.[27] The Shangqing school is the beginning of the Taoist tradition known as “inner alchemy” (neidan), a form of physical and spiritual self cultivation.[3]

It was in the later fifth century that an aristocratic scholar called Lu Xiujing (406–477) drew on all these disparate influences to shape and produce a common set of beliefs, texts and practices for what he called "the teachings of the Tao” (Dàojiào).[27] In the north, another influential figure, Kou Qianzhi (365–448), reformed the celestial master school, producing a new ethical code.

Xuanxue[edit]

Xuanxue (lit. "mysterious" or "deep" learning, sometimes called Neo-Taoism) was an important school of thought from the 3rd to 6th-century CE. Xuanxue philosophers combined elements of Confucianism and Taoism to reinterpret the Yijing, Daodejing, and Zhuangzi. Influential Xuanxue scholars include Wang Bi (226–249), He Yan (d. 249), Xiang Xiu (223?–300, part of the famous intellectual group known as the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove), Guo Xiang (d. 312), and Pei Wei (267–300).[3]

Thinkers like He Yan and Wang Bi set forth the theory that everything, including yīn and yáng and the virtue of the sage, “have their roots" in wú (nothingness, negativity, not-being).[28] What He Yan seems to mean by wú can be variously described as formlessness and undifferentiated wholeness. Wu is property-less and yet full and fecund.[28]

Wang Bi's commentary has traditionally been the most influential philosophical commentary on the Daodejing. Like He Yan, Wang Bi focuses on the concept of wú (non-being, nothingness) as the nature of the Tao and underlying ground of existence.[29] Wang Bi's view of wú is that it is "not being as a necessary basis of being". For being to be possible, there must be not-being, and as the Daodejing states, “Dao gives birth to [shēng] one” and “all things in the world are born of something (yǒu); something is born of nothing (wú)”. Wang Bi's account focuses on this foundational aspect of not-being.[28]

According to Livia Kohn, for Wang Bi "nonbeing is at the root of all and needs to be activated in a return to emptiness and spontaneity, achieved through the practice of nonaction, a decrease in desires and growth of humility and tranquility".[29] Another critical concept for Xuanxue philosophers is zìrán (lit. 'self-so', natural authenticity).[28]

Guo Xiang is also another influential Xuanxue thinker. In his commentary to the Zhuangzi, he rejected that wu was the source of the generation of beings, instead arguing for spontaneous “self-production” (zìshēng 自生) and “self-transformation” (zìhuà 自化) or “lone-transformation” (dúhuà 獨化):

Another key figure, Taoist alchemist Ge Hong (c. 283–343) was an aristocrat and government official during the Jin dynasty who wrote the classic known as the Baopuzi ("Master Embracing Simplicity"), a key Taoist philosophical work of this period.[3] This text includes Confucian teachings and also spiritual practices meant to aid in attaining immortality and a heavenly state called "great clarity", which had great influence on later Taoism.[30]

A later Xuanxue thinker, Zhang Zhan (c. 330–400), is known particularly for his commentary on the Liezi.[28] During the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), Xuanxue reached the height of influence as it was admitted into the official curriculum of the imperial academy.[28]

Tang dynasty[edit]

By the Tang dynasty times (618–907 CE), a common sense of a "Taoist identity" had developed (which Tang leaders called Dàojiào, "teachings of the Tao"), partly by the efforts of systematisers like Lu Xiujing and due to the need to compete against Buddhism for imperial patronage.[31] This synthetic system is sometimes called the Three Caverns. They collected the first Taoist canon, often called “The Three Arcana” (san-dong, 三洞), which did not originally include the Daodejing.[31]

Taoism gained official status in China during the Tang dynasty, whose emperors claimed Laozi as their relative.[32] The Gaozong Emperor added the Daodejing to the list of classics (jīng, 經) to be studied for the imperial examinations.[33] This was the height of Taoist influence in Chinese history.

Sima Chengzhen (647—735 CE) is an important intellectual figure of this period. He is especially known for blending Taoist, and Buddhist theories and forms of mental cultivation in the Taoist meditation text called the Zuowanglun. He served as an adviser to the Tang government.[31] He was later retroactively appropriated as a patriarch of the Quanzhen school.[34]

Another influential Daoist tradition from the Tang dynasty is the Twofold Mystery School (Chinese: 重玄, pinyin: Chóngxuán). Their philosophy was influenced by Buddhist Madhyamaka thought.[35] A key thinker from this tradition was Cheng Xuanying (成玄英, fl. 631–655), who is known for his influential commentaries on the Daodejing and Zhuangzi.

Another key Taoist writer and thinker of the Tang era is Du Guangting (850—933 CE). He produced an influential commentary on the Daodejing as well as numerous expositions of other scriptures and histories.

Song dynasty[edit]

The Song dynasty (960–1279) era saw the foundation of the Quanzhen (Complete perfection or Integrating perfection) school of Taoism during the 12th century among followers of Wang Chongyang (1113–1170), a scholar who wrote various collections of poetry and texts on living a Taoist life who taught that the "three teachings" (Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism), "when investigated, prove to be but one school". The Quanzhen school was syncretic, combining elements from Buddhism (such as monasticism) and Confucianism with past Taoist traditions.[3]

Neidan, a form of internal alchemy, became a major emphasis of the Quanzhen sect. Wang Chongyang taught that “immortality of the soul” (shén-xiān, 神仙) can be attained within this life by entering seclusion, cultivating one's “internal nature” (xìng, 性), and harmonizing them with one's “personal fate” (mìng-yùn, 命運)."[36] He taught that, by mental training and asceticism through which one reaches a state of no-mind (wú-xīn, 無心) and no-thoughts, attached to nothing, one can recover the primordial, deathless "radiant spirit" or "true nature" (yáng-shén 陽神, zhēn-xìng 真性).[37][a]

According to Stephen Eskildsen, Wang Chongyang appears to have been familiar with and influenced by Mahayana Buddhist texts like the Diamond sutra as well as Chan texts, however:

One Quanzhen master, Qiu Chuji, became a teacher of Genghis Khan before the establishment of the Yuan dynasty. Originally from Shanxi and Shandong, the sect established its main center in Beijing's Baiyunguan ("White Cloud Monastery").[39] Several Song emperors, most notably Huizong, were active in promoting Taoism, collecting Taoist texts and publishing editions of the Daozang.

Yuan and Ming dynasties[edit]

The Yuan and Ming government meanwhile often attempted to control and regulate Taoism. Taoism suffered a significant setback during the reign of Kublai Khan when many copies of the Daozang were ordered burned in 1281.[3] This destruction gave Taoism a chance to renew itself.[40] Chinese Taoists during the 12–14th centuries engaged in a revaluation of their tradition, dubbed by some a "reformation", which focused on individual cultivation.[41]

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the state promoted the notion that “the Three Teachings (Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism) are one”, an idea which over time became popular consensus.[42] The current Taoist textual canon, called the Daozang, was compiled during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).[43] Moreover, during the Ming dynasty, Taoist ideas also influenced Neo-Confucian thinkers like Wang Yangming and Zhan Ruoshui.[44]

Qing dynasty and modern China[edit]

The late Ming and early Qing dynasty saw the rise of the Longmen ("Dragon Gate" 龍門) school of Taoism, founded by Wang Kunyang (d. 1680) which reinvigorated the Quanzhen tradition.[45] Longmen Taoist writers such as Liu Yiming (1734–1821) also simplified Taoist “Inner Alchemy” practices making more accessible to the public by removing much of the esoteric symbolism of medieval texts.[46] It was Min Yide (1758–1836) though that became the most influential figure of the Longmen lineage, as he was the main compiler of the Longmen Daozang xubian and doctrine.[45] It was Min Yide who also made the famous text known as The Secret of the Golden Flower, along with its emphasis on internal alchemy, the central doctrinal scripture of the Longmen tradition.[45]

The fall of the Ming dynasty was blamed by some Chinese literati on Taoist influences and therefore they sought to return to a pure form of Han Confucianism during a movement called Hanxue, or "Han Learning" which excluded Taoism.[47] The study and practice of Taoist philosophy saw a steep decline in the more tumultuous times of the later Qing dynasty. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Taoism had declined considerably, and only one complete copy of the Daozang still remained, at the White Cloud Monastery in Beijing.[48]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ “You simply must be of no mind and no thoughts. Do not become attached to anything. Clearly, serenely, be free of affairs within and without. This is what it means to see your [Real] Nature.” - Eskildsen (2004), pp. 21, 31

References[edit]

- ^ Pollard, Rosenberg & Tignor (2011), p. 164

- ^ Creel (1982), p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Littlejohn (n.d.)

- ^ a b c d Hansen (2017)

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 12

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 74

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 16

- ^ a b Kirkland (2004), p. 18

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 75

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 23

- ^ Kirkland (2004), pp. 23–33

- ^ Kirkland (2004), pp. 53, 67

- ^ Kirkland (2004), pp. 58–59, 63

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 63

- ^ a b Kirkland (2004), p. 59

- ^ Kirkland (2004), pp. 41–42

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 41

- ^ a b Kirkland (2004), p. 46

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 68

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 7

- ^ Kohn (2008), p. 37

- ^ Kohn (2008), p. 4

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 80

- ^ Kohn (2000), p. 6

- ^ HUANG-LAO IDEOLOGY, Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno, http://www.indiana.edu/~g380/4.8-Huang-Lao-2010.pdf

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 85

- ^ a b Kirkland (2004), p. 87

- ^ a b c d e f g Chan (2017)

- ^ a b Kohn (2008), p. 26

- ^ Robinet (1997), p. 78; Kirkland (2004), p. 84

- ^ a b c Kirkland (2004), p. 90

- ^ Robinet (1997), p. 184

- ^ Robinet (1997), p. 185

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 104

- ^ Assandri, Friederike (2020). "Buddhist–Daoist Interaction as Creative Dialogue: The Mind and Dào in Twofold Mystery Teaching". In Anderl, Christoph; Wittern, Christian (eds.). Chán Buddhism in Dūnhuáng and Beyond: A Study of Manuscripts, Texts, and Contexts in Memory of John R. McRae. Numen Book Series. Vol. 165. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 363–390. doi:10.1163/9789004439245_009. ISBN 978-90-04-43191-1. ISSN 0169-8834.

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 106

- ^ Eskildsen (2004), pp. 21, 31

- ^ Eskildsen (2004), pp. 6–7

- ^ Robinet (1997), pp. 23–224

- ^ Schipper & Verellen (2004), p. 30

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 98

- ^ Kirkland (2004), pp. 107, 120

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 13

- ^ Kohn (2008), p. 178

- ^ a b c Esposito (2001)[pages needed]

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 112

- ^ Schipper (1993), p. 19

- ^ Schipper (1993), p. 220

Bibliography[edit]

- Assandri, Friederike (2020). "Buddhist–Daoist Interaction as Creative Dialogue: The Mind and Dào in Twofold Mystery Teaching". In Anderl, Christoph; Wittern, Christian (eds.). Chán Buddhism in Dūnhuáng and Beyond: A Study of Manuscripts, Texts, and Contexts in Memory of John R. McRae. Numen Book Series. Vol. 165. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 363–390. doi:10.1163/9789004439245_009. ISBN 978-90-04-43191-1. ISSN 0169-8834. S2CID 242842933.

- Chan, Alan (2017). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Neo-Daoism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 ed.).

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner (1982) [1970]. What Is Taoism?: And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226120478.

- Dean, Kenneth (1993). Taoist Ritual and Popular Cults of Southeast China. Princeton: Princeton University.

- Demerath, Nicholas J. (2003). Crossing the Gods: World Religions and Worldly Politics. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3207-8.

- Eskildsen, Stephen (2004). The Teachings and Practices of the Early Quanzhen Taoist Masters. SUNY series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791460450.

- Esposito, Monica (2001). "Longmen Taoism in Qing China: Doctrinal Ideal and Local Reality". Journal of Chinese Religions. 29 (1): 191–231. doi:10.1179/073776901804774604.

- Hansen, Chad (2017). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Daoism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 ed.).

- Hucker, Charles O. (1975). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8047-2353-2.

- Kirkland, Russell (2004). Taoism: The Enduring Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 9780415263221.

- Kohn, Livia (1993). The Taoist Experience: An Anthology. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Kohn, Livia, ed. (2000). Daoism Handbook. Leiden: Brill.

- Kohn, Livia (2004). The Daoist Monastic Manual: A Translation of the Fengdao Kejie. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kohn, Livia (2008). Introducing Daoism. Routledge. ISBN 9780415439978.

- Kohn, Livia; LaFargue, Michael, eds. (1998). Lao-Tzu and the Tao-Te-Ching. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-3599-7.

- Littlejohn, Ronnie (n.d.). "Daoist Philosophy". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002.

- Pollard, Elizabeth; Rosenberg, Clifford; Tignor, Robert (2011). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York, New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393918472.

- Robinet, Isabelle (1993) [1989]. Taoist Meditation: The Mao-shan Tradition of Great Purity. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Robinet, Isabelle (1997) [1992]. Taoism: Growth of a Religion. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2839-9.

- Schipper, Kristofer M. (1993) [1982]. The Taoist Body. Translated by Duval, Karen C. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520082243.

- Schipper, Kristopher; Verellen, Franciscus (2004). The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang. Chicago: University of Chicago.