2023/03/24

Reading the Qur'an as a Quaker

Reading the Qur’an as a Quaker

April 26, 2018

Quaker author Michael Birkel felt that we aren’t hearing the whole truth about Islam, so he went out to discover it for himself.

Thanks to this week’s sponsor:

Everence helps people and organizations live out their values and mission through faith-rooted financial services. Learn more.

Transcript:

There is within Islam a sacred saying called a “hadith,” in which God is speaking and God says, “I was a hidden treasure and I desired to be known.” This was one of the motivations of the act of creation itself. “I was a hidden treasure and I desired to be known.” If that desire— that deep desire—is imprinted on the very fabric of the universe, then our coming to know one another across religious boundaries is a sacred task and a holy opportunity.

Reading the Qur’an as a Quaker

We Quakers have a commitment—we call it a testimony—to truth telling. And it was pretty obvious to me that not the whole truth was being told about Islam or about Muslims. In the media we would hear about extremists who live far away and never hear about our Muslim neighbors who live here: what do they think?

Conversations About the Qur’an

So I traveled among Muslims who live from Boston to California, and I just had one question for them: would you please choose a passage in your holy book and talk to me about it? The result was a series of precious conversations, because what they brought to the conversation was their love for their faith, for God and for the experience they had of encountering God’s revelation through the Qur’an.

The Experience of Reading the Qur’an

One of my Muslim teachers told me, when I asked him, “what is it like to read the Qur’an?” and he said it’s this experience of overwhelming divine compassion. You feel yourself swept up into this divine presence where you feel so loved that nothing else matters. Any other desires you had in the world just disappear. You are where you want to be. At the same time, you feel this overwhelming sense of compassion for others. And he told me if you don’t feel that, you’re not reading the Qur’an.

A Diversity of Voices

I spoke with Muslims from many places that are within the spectrum of the Islamic community. I spoke to Sunnis, I spoke to Shiites, I spoke to Sufis, I spoke to men, I spoke to women. I spoke to people of many ethnic heritages. If there’s one thing I learned, it is that whatever you think Islam is, it’s wider than that.

One imam—who was by 39 generations removed a descendant of the prophet Muhammad himself—spoke to me and said that for him, one of the jewels of the Qur’an was this notion that you do not repel evil with evil. You drive away evil with goodness. And if you drive away evil with good, then you find that the person whom you regarded as your enemy can become your friend.

Another Muslim teacher taught me that according to the Qur’an, when we hear about good and evil, our task is not to divide the world into two teams—here are the good guys, here are the bad guys—but rather, our inclination towards evil is found in every heart and that is where the fundamental conflict resides. This to me sounded very close to the message of early Quakers.

Encountering the Qur’an as a Non-Muslim

I believe that for a non-Muslim, encountering the Qur’an for the first time might be perplexing. You might imagine being parachuted down into the book of Jeremiah. There you land: you don’t know the territory, here are these prophetic utterances (which is how Muslims see the Qur’an) and in Jeremiah they don’t always have names attached to them. They’re not in chronological order and they’re not thematically arranged. I believe the Qur’an can read like that to a newcomer. That’s why I think it’s valuable to read it in the company of persons who have been reading it their whole lives.

What is it like to read someone else’s scripture? I think it’s quite possible that it can change you in ways that I can’t predict for any reader, except to say that it will make your life richer. It will make your life better to know this. I am not a trained scholar of Islam. I did some preparation for this project, but mostly what I did was go out and talk to my neighbors, and it changed my life. And so I would like to encourage anyone who’s hearing these words to go out, cross religious boundaries, talk to their neighbors, because your life will be changed too.

Discussion Questions:

- Have you connected with someone across religious boundaries? How were you changed by the experience?

- Michael Birkel says that the Quaker commitment to truth telling inspired him to travel the country having conversations with Muslims in those areas. If you could embark on a similar project, what topic would you pick? How would you go about it?

The views expressed in this video are of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of Friends Journal or its collaborators.

2023/03/23

신라인도 유학 갔던 불교의 성지, 인도 날란다 - 오마이뉴스

신라인도 유학 갔던 불교의 성지, 인도 날란다

23.03.23

김찬호(widerstand365)

석가모니가 깨달음을 얻었다는 보드가야를 들른 뒤에도, 저는 불교 성치를 찾아 여행을 계속했습니다. 일반적이라면 석가모니가 돌아가신 쿠쉬나가르(Kushinagar)로 향하는 게 맞겠지만, 저는 잠시 파트나(Patna)에 들렸습니다.

파트나에서 기차를 타고 외곽으로 나오면 '날란다(Nalanda)'라는 마을에 갈 수 있습니다. 이곳에는 과거 인도의 불교 대학, 날란다 대승원의 유적이 남아 있죠. 날란다 대승원은 당나라의 현장대사나 의정대사를 비롯해 신라의 유학승도 여럿 수학했던 공간입니다. 인도 불교의 전성기를 만들어냈던 현장이지요.

날란다 대승원은 12세기까지 존속하다가, 인도에 이슬람 왕조가 들어서며 파괴됩니다. 이미 인도 내에서는 불교의 세력이 약화되고 있었죠. 날란다 대승원의 파괴는 인도 불교의 종언과도 같은 사건이었습니다. 지금 날란다 대승원은 파괴된 유적으로만 그 흔적을 찾을 수 있습니다.

관련사진보기

제가 날란다 대승원에 들른 것 역시, 인도 불교의 전성기와 최후를 함께한 현장을 보기 위해서였습니다. 파괴되었지만 여전히 장엄한 유적을 둘러보았습니다. 이제는 무너진 벽과 토대만 남아 있지만, 그 규모를 충분히 상상할 수 있었습니다.

날란다에서는 라즈기르로 향하는 합승 지프가 운행되고 있었습니다. 하지만 차 안은 물론 위에까지 사람이 가득 탄 지프를 탈 수는 없겠더군요. 어쩔 수 없이 값은 좀 나가겠지만 오토릭샤를 불러 움직이려는 찰나, 저쪽에서 저처럼 오토릭샤를 찾고 있는 스님 두 분이 눈에 띄었습니다.

낯선 사람에게 잘 다가가지 않는 저인데도, 순간 말을 붙였습니다. 역시나 라즈기르로 향한다는 스님들은 방글라데시에서 오신 분들이셨습니다. 함께 가시는 게 어떠냐고 물었고, 저와 스님들은 잠시 이야기를 나누다 곧 지나가던 차 한 대에 함께 올라탔습니다.

스님들의 목적지는 라즈기르의 방글라데시 사원이었습니다. 보드가야에서와 마찬가지로, 이곳에서도 순례자들을 위한 숙소를 마련해 두고 있는 모양이더군요. 스님들은 저에게 절의 숙소를 내어 주시려 했지만, 저는 이미 파트나의 숙소에 짐을 풀어둔 터라 사양했습니다. 사원의 불상 앞에 잠시 앉아 있다 나오면서도 그게 못내 아쉽더군요.

▲ 라즈기르의 방글라데시 사원

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

덕분에 무사히 라즈기르를 거쳐 파트나로 돌아온 뒤, 다음 향한 도시는 고락푸르(Gorakpur)였습니다. 일반적으로 이 도시는 바라나시를 비롯한 지역에서 네팔로 넘어갈 때 들르는 관문 도시지요. 하지만 여기서 로컬 버스를 타고 1시간 30분 정도를 달리면 쿠쉬나가르에 갈 수 있습니다.

생각해보면 인도에서 버스라는 걸 제대로 타 보는 게 처음이었습니다. 버스 터미널이라는 곳도 처음 들려봤습니다. 예상은 했지만 역시나 혼란 그 자체더군요. 정해지지 않은 플랫폼과 알 수 없는 목적지의 버스들, 그리고 곳곳에서 큰 소리로 울리는 경적 소리. 버스 안을 돌아다니는 상인들과, 버스 하나 타는 데 뭐가 그리 복잡한지 싸우고 있는 사람들.

하지만 그 와중에도 타야 할 버스를 찾는 외국인의 질문을 무시하는 사람은 거의 없었습니다. 버스를 찾아 "쿠쉬나가르?"라는 질문을 몇 번이나 반복한 끝에 정차해 있는 어느 버스에 탑승했습니다. 처음에는 넉넉했던 버스 안에 사람들이 가득찰 무렵, 버스는 출발합니다.

▲ 쿠쉬나가르로 향하는 버스

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

옆 자리에 아들을 안고 앉아 있던 아버지는, 쿠쉬나가르에 도착할 즈음이 되자 제게 손짓을 합니다. 힌디에 약간의 영어가 섞여 있었지만, 무슨 뜻인지는 충분히 알아들을 수 있었습니다. "아까 표를 사고 받은 영수증을 차장에게 보여주면 거스름돈을 줄 거야. 그걸 받아서 저 앞에서 내리면 돼."

그러고보니 아까 표를 사고도 거스름돈을 받지 못했습니다. 몇 루피 되지 않는 돈이라 그냥 그러려니 했는데, 덕분에 거스름돈까지 받아 쿠쉬나가르에 무사히 내렸습니다. 가득한 승객에 답답했던 버스 안에서 벗어나니 고요한 마을이 눈에 들어옵니다.

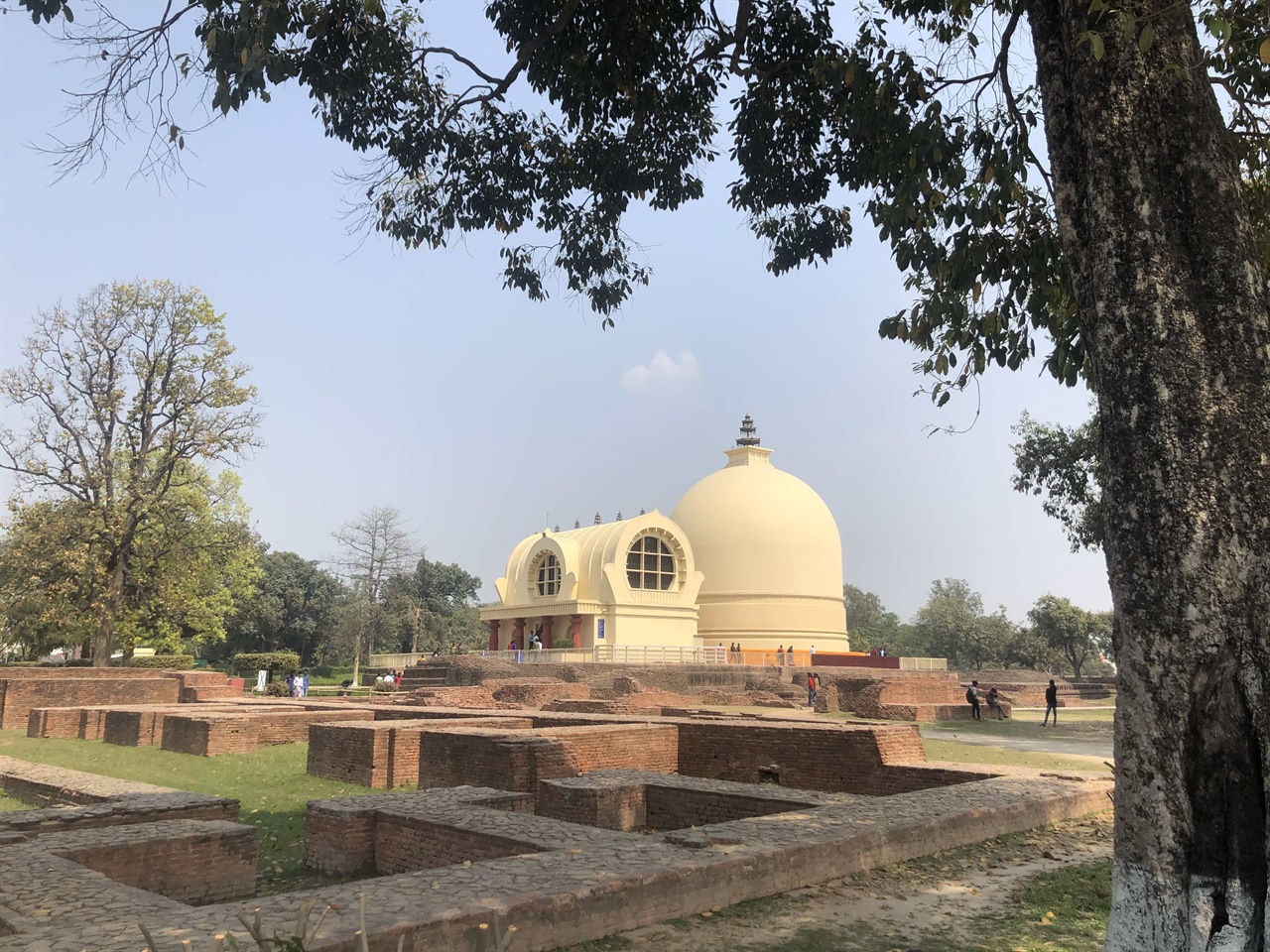

부처님이 열반에 들었다는 쿠쉬나가르. 이곳 역시 여러 나라에서 만든 사원이 곳곳에 들어서 있습니다. 한켠의 넓은 공원 안에는 와불을 모신 열반당도 세워져 있죠. 작은 마을은 걸어서도 쉽게 돌아볼 수 있었습니다.

쿠쉬나가르는 작은 마을이라 따로 버스 터미널이 없습니다. 돌아올 때는 내린 곳의 맞은편 길가에 서 지나가는 버스를 잡아 타야 했죠. 마을을 나오니 다행히 버스를 기다리고 있는 현지인들이 여럿 서 있더군요. 그들 사이에 끼어 버스를 타고, 다시 고락푸르까지 무사히 돌아왔습니다.

▲ 쿠쉬나가르 열반당

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

보드가야에서 날란다와 라즈기르, 그리고 쿠쉬나가르까지. 여러 불교 성지를 생각보다는 빠르게 돌아본 편이었습니다. 큰 실수나 일정의 지연 없이, 여행자가 적은 동네를 무사히 돌아다녔습니다. 그리고 그 사이에는 물론 여러 사람들의 도움이 있었죠.

쿠쉬나가르에서 돌아오는 길, 석가모니의 마지막 말씀을 생각했습니다. 이미 자신이 열반할 날이 얼마 남지 않았다고 말한 석가모니는, 쿠쉬나가르에 도착해 숲에 가사를 깔고 누웠습니다. 이곳에서 마지막 가르침을 행한 석가모니는 "존재하는 모든 것은 변한다. 게으름 없이 정진하라"라는 말을 남기고 열반에 들었습니다.

"게으름 없이 정진하라." 불교 성지를 돌아보며 만난 여러 스님들을 생각했습니다. 그런 사람들의 게으름 없는 정진이 모여 지금까지 이어지고 있는 것이겠죠. 보드가야와 쿠쉬나가르에 있던 각국의 사원들도 그렇게 모여 만들어진 것이겠지요.

하지만 그러면서도, 이제는 결국 폐허가 되어버린 날란다의 모습도 생각했습니다. 그들의 정진은 어디로 간 것일까요. 날란다의 사원에서 수행했던 수많은 스님들 가운데, 지금 우리가 알 수 있는 이름은 극소수에 불과합니다. 한때 1만 명의 학생이 살고 있었다던 날란다에서, 그 나머지의 이름은 어디로 사라지고 없는 것일까요.

▲ 날란다 역

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

그들의 수행과 공덕이 무엇이 되어 남았을지, 저는 알지 못합니다. 날란다의 건물들처럼 무너지고 쓰러졌을지도 모를 일이지요. 지금 우리가 게으름 없이 정진하고 노력하더라도, 그 역시 언젠가 폐허가 되어 흔적조차 남지 않을지도 모르겠습니다.

그러나 단 한 가지, 그 폐허를 찾아가는 여행자에게 누군가가 베푼 호의만은 제게 남았습니다. 주변의 낯선 사람에게, 아무런 주저함 없이 선뜻 내밀던 도움만은 제게 남았습니다. 적어도 그 기억만큼은 무너지지 않고 제 안에서 살아있을 것이라 생각합니다.

"존재하는 모든 것은 변한다. 게으름 없이 정진하라." 무엇을 향해 정진해야, 다른 '존재하는 것'들과는 달리 무너지지 않을 수 있을까요. 어쩌면 이 여행을 통해, 저는 제 나름의 답을 조금씩 찾아가는 중인지도 모르겠습니다.

덧붙이는 글 | 본 기사는 개인 블로그, <기록되지 못한 이들을 위한 기억, 채널 비더슈탄트>에 동시 게재됩니다.

불교 신자는 아닙니다만, 보리수 나무 아래 서니 - 오마이뉴스

불교 신자는 아닙니다만, 보리수 나무 아래 서니

23.03.22 08

김찬호(widerstand365)

콜카타에서 하룻밤 기차를 타고 제가 도착한 곳은 인도 비하르 주의 가야(Gaya)입니다. 사람들이 잘 찾지 않는 이 도시에 온 이유는 불교 성지를 방문하기 위해서입니다. 가야 역에서 오토릭샤를 타고 30여분, 곧 보드가야(Bodhgaya)에 도착합니다.

보드가야는 부처님이 깨달음을 얻은 곳으로 알려져 있습니다. 석가모니는 출가한 이후 혹독한 고행을 통해 깨달음을 얻고자 합니다. 하지만 6년의 고행 끝에도 깨달음을 얻지 못했죠. 석가모니는 육체를 괴롭히는 것만으로는 깨달음을 얻을 수 없겠다 생각하고 고행을 멈춥니다.

석가모니는 지나가던 '수자타'라는 소녀가 공양한 우유죽을 마십니다. 그리고 어느 보리수 나무 아래에 앉아 명상에 들었죠. 마왕의 유혹마저 모두 물리친 석가모니는 결국 그 자리에서 깨달음을 얻었습니다. 그곳이 지금의 보드가야입니다.

▲ 보드가야 시내 풍경

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

보드가야는 석가모니의 탄생지인 룸비니, 최초 설법지인 사르나트, 입멸지인 쿠쉬나가르와 함께 불교의 4대 성지로 불립니다. 석가모니가 깨달음을 얻은 보리수 나무 주변으로는 '마하보디 사원'이라는 사원이 들어서 있습니다. 주변 마을에는 세계 각지의 불교도가 만든 사원이 세워져 있죠.

태국이나 스리랑카, 미얀마처럼 불교의 영향력이 강한 국가들은 그만큼 넓고 화려한 사원을 세웠습니다. 일본은 거대한 불상을 세웠고, 대만 역시 사원을 만들었습니다. 한국은 '고려사'라는 절을 세웠고, 지금은 '분황사'라는 새로운 사찰을 건설 중에 있습니다.

여행자들이 적은 비하르 주이지만, 보드가야에서만은 불교 수행자들을 중심으로 여러 방문객을 만날 수 있습니다. 수행자들 뿐 아니라 일반인들에게도 묵을 공간을 내어주는 절들이 많습니다. 저 역시 마을을 잠시 돌아다닌 뒤, 어느 절에 짐을 풀었습니다.

▲ 다이조쿄 대불

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

제가 보드가야에 방문했을 때는 인도의 축제인 홀리 기간이었습니다. 물과 염료를 뿌리며 노는 축제 기간인데도 마을 안은 조용했습니다. 마을을 떠나는 날, 가야 시내에서 벌어지고 있는 홀리 축제 현장을 보고 아주 놀랐을 정도였으니까요.

사실 저는 불교 신자는 아닙니다. 애초에 종교를 가지고 있지 않은 사람입니다. 불교 미술을 공부하거나 불경을 사료로서 공부한 적은 있지만, 불교 철학에 대해서는 별로 아는 바가 없기도 합니다. 제가 공부한 역사학과 철학은 인문학 안에서는 가장 거리가 있는 학문이기도 하고요.

하지만 이 성지에서 만난 불교는 제게 특별했습니다. 책이나 미술품으로 보던 불교와는 달랐습니다. 아무런 대가도 이유도 없이 종교에 정진하는 사람들을 만났기 때문일까요. 어떠한 응답도 없는 진리에 모든 것을 바칠 준비가 되어 있는 사람들을 만났기 때문일까요.

▲ 마하보디 사원

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

생각해보면 나무 한 그루에 불과합니다. 그 아래에서 깨달음을 얻은 한 명의 수행자였습니다. 하지만 그를 따라가려는 수없는 사람들이 있었습니다. 그를 따라 진리를 갈구하던 수행자들이 지난 2500여 년 간 끊어지지 않고 긴 길을 만들었습니다. 마하보디 사원 앞, 조용히 명상을 하는 수행자들을 통해 그 길은 지금까지 이어지고 있습니다.

앞으로 또 얼마나 이어질지 모르는 긴 길 위에서, 그저 자신의 역할을 다할 뿐인 사람들입니다. 다만 갈 수 있는 곳까지 갈 뿐인 사람들이죠. 그 다음의 일은 굳이 생각할 필요조차 없습니다. 눈 앞의 정념을 떼어내는 데 모든 것을 바칠 뿐입니다.

종교인의 삶이란 그런 것이겠죠. 사실 종교를 가지지 못한 제가 상상할 수 있는 영역은 아닐 것입니다. 하지만 온 생을 바쳐 무엇인가에 정진하고 궁구할 수 있는 삶을 저는 동경합니다. 그것이 흔치 않은 성지순례지에 제가 온 이유일 수도 있겠습니다.

▲ 마하보디 사원의 보리수나무

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

석가모니의 제자였던 유마거사의 이야기를 다룬 <유마힐소설경>에서는 이렇게 말합니다. 우리가 욕망에 흔들리는 것은 두려움이 있기 때문이라고요. 이미 두려움을 떠난 자에게는 모든 오욕이 할 수 있는 바가 없다고요.

왠지 잠시 곁을 내어주는 듯한 보리수 나무 근처에 앉아, 저도 잠시 편안한 마음으로 생각에 잠겼습니다. 내가 가진 두려움에 대해 생각했습니다. 오늘 하루의 이야기일 수도, 이번 여행의 이야기일 수도, 혹은 삶 전체를 둔 이야기일 수도 있겠지요.

그 모든 두려움을 이기고, 불신자인 제가 갈구할 수 있는 진리는 무엇일까요. 눈 앞에 보이는 스님들처럼, 저는 그것에 제 삶을 바칠 준비가 되어 있는 것일까요? 그럴 용기를 가진 사람일까요? 그렇지 않다면, 의탁할 신조차 없는 저는 그 용기를 어디에서 찾아야 할까요.

▲ 보드가야의 한국 절, 분황사

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

보드가야의 보리수나무 아래에서 석가모니가 얻었다는 깨달음이 무엇인지 저야 알지 못합니다. 사성제(四聖諦)니 팔정도(八正道)니 하는 글자만으로 배울 수 있는 것도 아니겠지요.

다만 오늘까지도, 지난 2500여 년을 한 순간도 끊이지 않고 이어졌을 수행자들의 긴 역사를 생각합니다. 그들 가운데 하나쯤은 저처럼 작고, 확신하지 못하고, 때로 비겁하지 않았을까 마음껏 상상해 봅니다.

종교에 발도 제대로 담가보지 못한 저는, 다만 그런 사실에서 조금이나마 위로를 얻습니다. 저와 같은 사람들의 발걸음을 따라 이 긴 길이 이어졌다는 사실. 대가 없이 진리를 바라고, 더 옳고 바르고 평등한 것을 따라 걸어간 사람들이 한 시대도 놓치지 않고 있었다는 사실. 그리고 그 역사가 지금 제 눈 앞에서까지 계속해서 이어지고 있다는 사실.

불신자에게 성지란 별 의미 없는 땅일지도 모른다고 생각했습니다. 하지만 그런 사실들을 확인하는 것만으로도, 제겐 충분한 용기이고 힘이었습니다. 의탁할 신이 없는 저 역시, 성지의 보리수 나무 아래에서만큼은 어떤 두려움을 잠시나마 끊어낼 수 있었던 기분입니다.

덧붙이는 글 | 본 기사는 개인 블로그, <기록되지 못한 이들을 위한 기억, 채널 비더슈탄트>에 동시 게재됩니다.

저작권자(c) 오마이뉴스(시민기자), 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지 오탈자 신고

태그:#세계일주, #성지순례, #보드가야, #세계여행, #인도

Chamunda - Wikipedia

Chamunda

| Chamunda | |

|---|---|

Goddess of war and "epidemics of pestilent diseases, famines, and other disasters".[1] | |

14th century Newari sculpture of Chamunda. | |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Cāmuṇḍā |

| Devanagari | चामुण्डा |

| Affiliation | Durga, Adi parashakti, Parvati, Kali, Mahakali |

| Abode | Cremation grounds or fig trees |

| Mantra | ॐ ऐं ह्रीं क्लीं चामुण्डायै विच्चे oṁ aiṁ hrīṁ klīṁ cāmuṇḍāyai vicce |

| Weapon | Trident and Sword |

| Mount | buffalo[2] or Dhole[3] Corpse (Preta) |

| Consort | Shiva as Bheeshana Bhairava or Bhoota Bhairava |

| Part of a series on |

| Shaktism |

|---|

|

show Schools |

show Practices |

show Festivals and temples |

Chamunda (Sanskrit: चामुण्डा, ISO-15919: Cāmuṇḍā), also known as Chamundeshwari, Chamundi or Charchika, is a fearsome form of Chandi, the Hindu Divine Mother Shakti and is one of the seven Matrikas (mother goddesses).[4]

She is also one of the chief Yoginis, a group of sixty-four or eighty-one Tantric goddesses, who are attendants of the warrior goddess Parvati.[5] The name is a combination of Chanda and Munda, two monsters whom Chamunda killed. She is closely associated with Kali, another fierce aspect of Parvati. She is identified with goddesses Parvati, Kali or Durga.

The goddess is often portrayed as residing in cremation grounds or around holy fig trees. The goddess is worshipped by ritual animal sacrifices along with offerings of wine. The practice of animal sacrifices has become less common with Shaivite and Vaishnavite influences.[citation needed]

Origins[edit]

Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar says that Chamunda was originally a tribal goddess, worshipped by the tribals of the Vindhya mountains in central India. These tribes were known to offer goddesses animal as well as human sacrifices along with rituals offering liquor. These methods of worship were retained in Tantric worship of Chamunda, after assimilation into Hinduism. He proposes the fierce nature of this goddess is due to her association with Rudra (Shiva), identified with fire god Agni at times.[6] Wangu also backs the theory of the tribal origins of the goddess.[7]

Iconography[edit]

Chamunda, 11th-12th century, National Museum, Delhi. The ten-armed Chamunda is seated on a corpse, wearing a necklace of severed heads.

The black or red coloured Chamunda is described as wearing a garland of severed heads or skulls (Mundamala). She is described as having four, eight, ten or twelve arms, holding a Damaru (drum), trishula (trident), sword, a snake, skull-mace (khatvanga), thunderbolt, a severed head and panapatra (drinking vessel, wine cup) or skull-cup (kapala), filled with blood. Standing on a corpse of a man (shava or preta) or seated on a defeated demon or corpse (pretasana). Chamunda is depicted adorned by ornaments of bones, skulls, and serpents. She also wears a Yajnopavita (a sacred thread worn by mostly Hindu priests) of skulls. She wears a jata mukuta, that is, headdress formed of piled, matted hair tied with snakes or skull ornaments. Sometimes, a crescent moon is seen on her head.[8][9] Her eye sockets are described as burning the world with flames. She is accompanied by evil spirits.[9][10] She is also shown to be surrounded by skeletons or ghosts and beasts like jackals, who are shown eating the flesh of the corpse which the goddess sits or stands on. The jackals and her fearsome companions are sometimes depicted as drinking blood from the skull-cup or blood dripping from the severed head, implying that Chamunda drinks the blood of the defeated enemies.[11] This quality of drinking blood is a usual characteristic of all Matrikas, and Chamunda in particular. At times, she is depicted seated on an owl, her vahana (mount or vehicle) or buffalo[12] and or Dhole.[13] Her banner figures an eagle.[9]

These characteristics, a contrast to usual Hindu goddess depiction with full breasts and a beautiful face, are symbols of old age, death, decay and destruction.[14] Chamunda is often said as a form of Kali, representing old age and death. She appears as a frightening old woman, projecting fear and horror.[15][16]

Hindu legends[edit]

The Goddess Ambika (here identified with: Durga or Chandi) leading the Eight Matrikas in Battle Against the Demon Raktabīja, Folio from a Devi Mahatmya - (top row, from the left) Narasimhi, Vaishnavi, Kumari, Maheshvari, Brahmi. (bottom row, from left) Varahi, Aindri and Chamunda, drinking the blood of demons (on right) arising from Raktabīja's blood and Ambika.

The Great Goddess in Her Chamunda Form. Mughal miniature, possibly from a scroll of the Devi Mahatmya, c. 1565-1575. Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh

In Hindu scripture Devi Mahatmya, Chamunda emerged as Chandika Jayasundara from an eyebrow of goddess Kaushiki, a goddess created from "sheath" of Durga and was assigned the task of eliminating the demons Chanda and Munda, generals of demon kings Shumbha-Nishumbha. She fought a fierce battle with the demons, ultimately killing them.[17]

According to a later episode of the Devi Mahatmya, Durga created Matrikas from herself and with their help slaughtered the demon army of Shumbha-Nishumbha. In this version, Kali is described as a Matrika who sucked all the blood of the demon Raktabīja, from whose blood drop rose another demon. Kali is given the epithet Chamunda in the text.[18] Thus, the Devi Mahatmya identifies Chamunda with Kali.[19]

In the Varaha Purana, the story of Raktabija is retold, but here each of Matrikas appears from the body of another Matrika. Chamunda appears from the foot of the lion-headed goddess Narasimhi. Here, Chamunda is considered a representation of the vice of tale-telling (pasunya). The Varaha Purana text clearly mentions two separate goddesses Chamunda and Kali, unlike Devi Mahatmya.[9]

According to another legend, Chamunda appeared from the frown of the benign goddess Parvati to kill demons Chanda and Munda. Here, Chamunda is viewed as a form of Parvati.[20]

The Matsya Purana tells a different story of Chamunda's origins. She with other matrikas was created by Shiva to help him kill the demon Andhakasura, who has an ability - like Raktabīja - to generate from his dripping blood. Chamunda with the other matrikas drinks the blood of the demon ultimately helping Shiva kill him.[9] Ratnakara, in his text Haravijaya, also describes this feat of Chamunda, but solely credits Chamunda, not the other matrikas of sipping the blood of Andhaka. Having drunk the blood, Chamunda's complexion changed to blood-red.[21] The text further says that Chamunda does a dance of destruction, playing a musical instrument whose shaft is Mount Meru, the string is the cosmic snake Shesha and gourd is the crescent moon. She plays the instrument during the deluge that drowns the world.[10]

Association with Matrikas[edit]

Chamunda is one of the saptamatrikas or Seven Mothers. The Matrikas are fearsome mother goddesses, abductors and eaters of children; that is, they were emblematic of childhood pestilence, fever, starvation, and disease. They were propitiated in order to avoid those ills, that carried off so many children before they reached adulthood.[15] Chamunda is included in the Saptamatrika (seven Matrikas or mothers) lists in the Hindu texts like the Mahabharata (Chapter 'Vana-parva'), the Devi Purana and the Vishnudharmottara Purana. She is often depicted in the Saptamatrika group in sculptures, examples of which are Ellora and Elephanta caves. Though she is always portrayed last (rightmost) in the group, she is sometimes referred to as the leader of the group.[22] While other Matrikas are considered as Shaktis (powers) of male divinities and resemble them in their appearance, Chamunda is the only Matrika who is a Shakti of the great Goddess Devi rather than a male god. She is also the only Matrika who enjoys independent worship of her own; all other Matrikas are always worshipped together.[23]

The Devi Purana describe a pentad of Matrikas who help Ganesha to kill demons.[24] Further, sage Mandavya is described as worshipping the Māṭrpaňcaka (the five mothers), Chamunda being one of them. The mothers are described as established by the creator god Brahma for saving king Harishchandra from calamities.[25] Apart from usual meaning of Chamunda as slayer of demons Chanda and Munda, the Devi Purana gives a different explanation: Chanda means terrible while Munda stands for Brahma's head or lord or husband.[26]

In the Vishnudharmottara Purana - where the Matrikas are compared to vices - Chamunda is considered as a manifestation of depravity.[27] Every matrika is considered guardian of a direction. Chamunda is assigned the direction of south-west.[20]

Chamunda, being a Matrika, is considered one of the chief Yoginis, who are considered to be daughters or manifestations of the Matrikas. In the context of a group of sixty-four yoginis, Chamunda is believed to have created seven other yoginis, together forming a group of eight. In the context of eighty-one yoginis, Chamunda heads a group of nine yoginis.[5]

Worship[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

A South Indian inscription describes ritual sacrifices of sheep to Chamunda.[28] In Bhavabhuti's eighth century Sanskrit play, Malatimadhva describes a devotee of the goddess trying to sacrifice the heroine to Chamunda's temple, near a cremation ground, where the goddess temple is.[29] A stone inscription at Gangadhar, Rajasthan, deals with a construction to a shrine to Chamunda and the other Matrikas, "who are attended by Dakinis" (female demons) and rituals of daily Tantric worship (Tantrobhuta) like the ritual of Bali (offering of grain).[30]

The Chapa dynasty worshiped her as their Kuladevi. The Kutch Gurjar Kshatriyas worship her as Kuladevi and temples are in Sinugra and Chandiya. Alungal family, a lineage of Mukkuva caste — (Hindu caste of seafarer origin) in Kerala — worship Chamundi in Chandika form, as Kuladevta and temple is in Thalikulam village of Thrissur, Kerala. This is an example of Chamunda worship across caste sects.

Temples[edit]

- In the Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh, around 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) west of Palampur, is the renowned Chamunda Devi Temple which depicts scenes from the Devi Mahatmya, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The goddess's image is flanked by the images of Hanuman and Bhairava. Another temple, Chamunda Nandikeshwar Dham, also found in Kangra, is dedicated to Shiva and Chamunda. According to a legend, Chamunda was enshrined as chief deity "Rudra Chamunda", in the battle between the demon Jalandhara and Shiva.

- In Gujarat, two Chamunda shrines are on the hills of Chotila and Parnera.

- There are multiple Chamunda temples in Odisha. The 8th-century Baitala Deula is the most prominent of them, also being one of the earliest temples in Bhubaneswar. The Mohini temple and Chitrakarini temple in Bhubaneswar are also dedicated to Chamunda. Kichakeshwari Temple, near the Baripada and Charchika Temple, near Banki enshrine forms of Chamunda.

- Another temple is Chamundeshwari Temple on Chamundi Hill, Mysore. Here, the goddess is identified with Durga, who killed the buffalo demon, Mahishasura. Chamundeshwari or Durga, the fierce form of Shakti, a tutelary deity held in reverence for centuries by the Maharaja of Mysore.

- The Chamunda Mataji temple in Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur, was established in 1460 after the idol of the goddess Chamunda — the Kuladevi and iṣṭa-devatā (tutelary deity) of the Parihar rulers — was moved from the old capital of Mandore by the then-ruler Jodha of Mandore. The goddess is still worshiped by the royal family of Jodhpur and other citizens of the city. The temple witnesses festivities in Dussehra: the festival of the goddess.

- Another temple, Sri Chamundeshwari Kshetram is near Jogipet, in Medak District in Telangana State.

- Sree Shakthan Kulangara temple is one of Chamundeshwari temples. It is located in Koyilandy, Kozhikode District in Kerala.

- One Chamunda Mata temple is situated in Dewas, Madhya Pradesh, It is situated on a hill top named Tekri above 300 feet. Chamunda Mata in Dewas is also called Choti Mata (the younger sister of Tulja mata, situated at the same hill top).[31]

In Buddhism[edit]

In Vajrayana Buddhism, Chamunda is associated with Palden Lhamo. She is seen as a wrathful form of Kali and is a consort of Mahakala and protectress of the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama of the Gelug school. [32]

In Jainism[edit]

Early Jains were dismissive of Chamunda, the goddess who demands blood sacrifice - which is against the primary principle of Ahimsa of Jainism. Some Jain legends portray Chamunda as a goddess defeated by Jain monks like Jinadatta and Jinaprabhasuri.[33]

Another Jain legend tells the story of conversion of Chamunda into a Jain goddess. According to this story, Chamunda sculpted the Mahavir image for the temple in Osian and was happy with the conversions of Hindu Oswal clan to Jainism. At the time of Navaratri, a festival that celebrates the Hindu Divine Mother, Chamunda expected animal sacrifices from the converted Jains. The vegetarian Jains, however, were unable to meet her demand. Jain monk Ratnaprabhasuri intervened, and as a result, Chamunda accepted vegetarian offerings, forgoing her demand for meat and liquor. Ratnaprabhasuri further named her Sacciya, one who had told the truth, as Chamunda had told him the truth that a rainy season stay in Osian was beneficial for him. She also became the protective goddess of the temple and remained the clan goddess of the Osvals. The Sachiya Mata Temple in Osian was built in her honour by Jains.[34] Some Jain scriptures warn of dire consequences of worship of Chamunda by the Hindu rites and rituals.[35] Many Kshatriyas and even the Jain community worship her as her Kuladevi or family/clan deity.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Nalin, David R. (15 June 2004). "The Cover Art of the 15 June 2004 Issue". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 39 (11): 1741–1742. doi:10.1086/425924. PMID 15578390.

- ^ "Goddess Chamundi".

- ^ "Sapta Matrika | 7 Matara - Seven Forms of Goddess Shakti".

- ^ Wangu p.72

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wangu p.114

- ^ Vaisnavism Saivism and Minor Religious Systems By Ramkrishna G. Bhandarkar, p.205, Published 1995, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-0122-X

- ^ Wangu p.174

- ^ See:

- Kinsley p. 147, 156. Descriptions as per Devi Mahatmya, verses 8.11-20

- "Sapta Matrikas (12th C AD)". Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Andhra Pradesh. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- Donaldson, T. "Chamunda, The fierce, protective eight-armed mother". British Museum.

- "Chamunda, the Horrific Destroyer of Evil [India, Madhya Pradesh] (1989.121)". In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ho/07/ssn/ho_1989.121.htm (October 2006)

- Kalia, pp.106–109.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Goswami, Meghali; Gupta, Ila; Jha, P. (March 2005). "Sapta Matrikas In Indian Art and their significance in Indian Sculpture and Ethos: A Critical Study" (PDF). Anistoriton Journal. Anistoriton. Retrieved 2008-01-08. "Anistoriton is an electronic Journal of History, Archaeology and ArtHistory. It publishes scholarly papers since 1997 and it is freely available on the Internet. All papers and images since vol. 1 (1997) are available on line as well as on the free Anistorion CD-ROM edition."

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kinsley p.147

- ^ "Durga: Avenging Goddess, Nurturing Mother ch.3, Chamunda". Norton Simon Museum. Archived from the original on 2006-10-03.

- ^ "Goddess Chamundi".

- ^ "Sapta Matrika | 7 Matara - Seven Forms of Goddess Shakti".

- ^ Wangu p.94

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Ancient India".

- ^ "Glossary of Asian Art".

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 81.

- ^ Kinsley p. 158, Devi Mahatmya verses 10.2-5

- ^ "Devi: The Great Goddess". www.asia.si.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-06-09. Retrieved 2017-05-29.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Moor p.118

- ^ Handelman pp.132–33

- ^ Handelman p.118

- ^ Kinsley p.241 Footnotes

- ^ Pal in Singh p.1840, Chapters 111-116

- ^ Pal in Singh p.1840, Chapter 116(82-86)

- ^ Pal p.1844

- ^ Kinsley p. 159

- ^ Kinsley p.146

- ^ Kinsley p.117

- ^ Joshi, M.C. in Harper and Brown, p.48

- ^ "History of Chamunda Tekri is centuries old". Free Press Journal. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ Srivastava, Sonal (10 July 2011). "The Goddess Sutra". Retrieved 13 December 2022.

"Chamunda is a form of Kali; she is protector, just like Palden Lhamo in Tibetan Buddhism," says Tsundu Dolma, a student of Tibetan Medicine, I'd met at an interfaith tour earlier in Karnataka. Palden Lhamo is protector of Buddha's teachings in the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. She is Mahakala's consort and venerated as guardian deity of Tibet, the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lamas.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Jainism By Narendra Singh, Published 2001, Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., ISBN 8126106913, p.705

- ^ Babb, Lawrence A. Alchemies of Violence: Myths of Identity and the Life of Trade in Western India, Published 2004, 254 pages, ISBN 0761932232 pp.168–9, 177-178.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Jainism By Narendra Singh p.698

Further reading[edit]

- Wangu, Madhu Bazaz (2003). Images of Indian Goddesses. Abhinav Publications. 280 pages. ISBN 81-7017-416-3.

- Pal, P. The Mother Goddesses According to the Devipurana in Singh, Nagendra Kumar, Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Published 1997, Anmol Publications PVT. LTD.,ISBN 81-7488-168-9

- Kinsley, David (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06339-2

- Kalia, Asha (1982). Art of Osian Temples: Socio-Economic and Religious Life in India, 8th-12th Centuries A.D. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 0-391-02558-9.

- Handelman, Don. with Berkson Carmel (1997). God Inside Out: Siva's Game of Dice, Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-510844-2

- Moor, Edward (1999). The Hindu Pantheon, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-0237-4. First published: 1810.