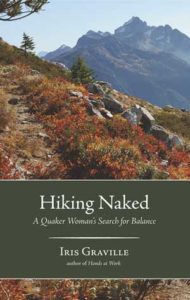

Hiking Naked: A Quaker Woman’s Search for Balance

Reviewed by Beth Taylor

November 1, 2017

By Iris Graville. Homebound Publications, 2017. 260 pages. $17.95/paperback; eBook coming December 2017.

By Iris Graville. Homebound Publications, 2017. 260 pages. $17.95/paperback; eBook coming December 2017.Buy from QuakerBooks

This wonderful memoir tells the story of a Quaker woman and her family as they leave city life behind and seek a simpler life deep in the mountains east of Seattle, Wash. Burned out after years of nursing and seemingly fruitless public health interventions, Iris Graville retreats with her husband, Jerry, and their 13-year-old twin son and daughter to an isolated lake deep in the North Cascade Mountains. Her family looks for adventure. She finds solace in the lush landscape, quiet dirt roads, baking, and writing.

The “hiking naked” part of the story does not refer to the like-minded sporting groups you can find online, but to the moment a year earlier when Graville realized she needed to change her life. Hot and exhausted as she and Jerry hike high into the mountains on their yearly getaway alone together, their twins happily staying with a grandmother, Graville stops and wonders if she can walk another step. Slowly she rounds a bend and sees her husband standing there, waiting for her, naked and grinning. It is her sign, and the metaphor for her journey to come—to lighten up, count her blessings, let go of heavy baggage, and hold on to what really matters.

Stehekin—a Salish word that means “the way through”—becomes their next stop together. A tiny community of 85 residents, the village is accessible only by boat, floatplane, or hiking. The kids become the seventh-graders of the one-room schoolhouse. Jerry becomes the bus driver. Iris becomes a baker, bicycling to work in the early morning darkness on the dirt road down to the village. Hours off fill with chores—chopping wood, repairing plumbing, and cooking—punctuated by trail hikes and cross-country skiing.

Food is planned a week ahead, the handwritten list sent by ferry down the lake to the friendly grocer, who sends the boxes back in a day or two. Occasionally a black bear wanders into the backyard; winter snow piles up against the windows; a forest fire threatens to sweep down into the valley; and a spring flood strands them for three days—nature’s way of reminding them of their powerlessness. Trees fall onto power lines, leaving some evenings brightened only by candles and kerosene lamps. With no phone, no TV, no Internet, the family embraces old entertainments anew. They read books, play board games, learn to juggle, make block prints for Christmas, and write letters to friends and family.

Graville embraces this rustic life as a way to simplify—leave behind the noise of highways, crowded urban streets, and schools with hundreds of students. Most important, though, she knows she needs to let go of 20 years of anxieties about her job, in particular, her fears of inadequacy in the face of the overwhelming human needs of her patients.

A practicing Quaker, she feels at home in the deep quiet of the woods. When the summer tourists leave and the bakery closes for the winter, she uses the silent days to write in her journal, waiting for “the still, small voice” as in Quaker meeting, seeking insight into the past that had tied her in knots, and writing her way into a calling to come. As she “attends to what is important”—the tasks of family life in a small, close-knit community and her times alone—she discovers that “the smallest touch, the briefest contact, the quietest diligence can make a difference—can change the course of a river.”

In the end, through solitude amidst the pines, family support, and deep friendships old and new, she finds a spiritual footing to carry her into her next chapter. Their family will move to Lopez Island off the coast of Washington state, larger and more developed than Stehekin but offering similar kinds of quiet and leadings through natural beauty.

And Graville will continue to write. Her essay “Seeking Clearness with Work Transitions” was published in the February 2015 issue of Friends Journal. She has also published the award-winning Hands at Work: Portraits and Profiles of People Who Work with Their Hands; and Bounty: Lopez Island Farmers, Food, and Community. Now, she publishes Shark Reef literary magazine. This eloquent memoir shows the move to Stehekin was indeed her “way through” to her new calling as a writer.

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Hiking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance

Want to Read

Rate this book

1 of 5 stars2 of 5 stars3 of 5 stars4 of 5 stars5 of 5 stars

Hiking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance

by Iris Graville (Goodreads Author)

4.15 · Rating details · 144 ratings · 49 reviews

Knocked off her feet after twenty years in public health nursing, Iris Graville quit her job and convinced her husband and their thirteen-year-old twin son and daughter to move to Stehekin, a remote mountain village in Washington State’s North Cascades. They sought adventure; she yearned for the quiet and respite of this community of eighty-five residents accessible only by boat, float plane, or hiking. Hiking Naked chronicles Graville’s journey through questions about work and calling as well as how she coped with ordering groceries by mail, black bears outside her kitchen window, a forest fire that threatened the valley, and a flood that left her and her family stranded for three days. (less)

GET A COPY

KoboOnline Stores ▾Book Links ▾

Paperback, 260 pages

Published September 12th 2017 by Homebound Publications

ISBN1938846842 (ISBN13: 9781938846847)

Edition LanguageEnglish

URLhttp://homeboundpublications.com/hiking-naked-by-iris-graville/

Other Editions (2)

HIking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance

111x148

All Editions | Add a New Edition | Combine

...Less DetailEdit Details

FRIEND REVIEWS

Recommend This Book None of your friends have reviewed this book yet.

READER Q&A

Ask the Goodreads community a question about Hiking Naked

54355902. uy100 cr1,0,100,100

Ask anything about the book

Be the first to ask a question about Hiking Naked

LISTS WITH THIS BOOK

Naked Lunch by William S. BurroughsNaked by David SedarisJuliet, Naked by Nick HornbyHow to Flirt with a Naked Werewolf by Molly HarperThe Naked and the Dead by Norman Mailer

Naked Titles

272 books — 21 voters

More lists with this book...

COMMUNITY REVIEWS

Showing 1-30

Average rating4.15 · Rating details · 144 ratings · 49 reviews

Search review text

English (48)

More filters | Sort order

Sejin,

Sejin, start your review of Hiking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance

Write a review

Gretchen Wing

Oct 12, 2017Gretchen Wing rated it it was amazing

If you are making or contemplating a major life transition, you will love this book. If you are yearning for more spiritual depth in your life, you will love this book. If you love the mountains and the feeling of being transported to the banks of a clear, rushing creek simply by turning pages, you will love this book. If you love finding your own family conflicts, joys, heartbreak, and sweet daily celebrations reflected in someone else's experience, you will love this book. Get the picture? Iris writes with unpretentious skill, making the ordinary extraordinary. (less)

flag5 likes · Like · 1 comment · see review

Brynnen Ford

Jul 16, 2018Brynnen Ford rated it it was amazing

Loved the stories, the insight, and just the writing was a joy to experience. It was fun to listen for Quaker themes, but it really was a universal story of a woman's search for work-life-spirit-balance and exploring ideas of calling and meaningful work.

Thank you for the opportunity! I hightly recommend it to all readers who enjoy memoir-type stories. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Yi_Shun

Oct 15, 2017Yi_Shun rated it it was amazing

Deepy satisfying, on a storytelling level and a spiritual level. Yes, even for those of us who don’t read “spiritual” books. This is the story of one family’s transition from city to rural life to their own brand of equilibrium. It’s worth every page.

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Julene

Oct 23, 2020Julene rated it really liked it

Shelves: memoir

This was a good memoir to read during covid time. I found it in a Free Book Library and the title drew me to take a look. Iris Graville, a white woman and a Quaker, in her 40s asks questions about her work, life, and purpose. She is in a stable, secure attached, relationship with two children who are twins. She has a good job in Bellingham, Wa, working in Public Health, but she's burnt out and questioning her path. I related to her questioning immediately.

Her family has started the tradition of ...more

flag1 like · Like · see review

Leigh Anne

Apr 06, 2018Leigh Anne rated it liked it

Burn out, or fade away?

Iris Graville was completely done with being a nurse. Although it had been her dream to help improve public health, she just couldn't anymore with the long hours, endless policy debates, and difficult patients (people are not always at their kindest when they are sick, and nurses bear the brunt of it). She needed a break from her life and some time to think through her next move, hopefully with some guidance from the still small voice inside her (as Quakers do). With her family's blessing and help, they decided to spend a year in a remote village in northern Washington State, only accessible by ferry, and with a grand total of 85 residents. Will stepping out of the rat race bring clarity? Or will it just make the Graville's slightly less stressed rats?

Anybody who's ever had a customer service job wlil relate to the burnout aspects, though you could make the argument that being able to up and change directions like this is a pretty privileged thing to do. Luckily Iris is aware of this, and remarks on it often. Life in the village is both beautiful and rough, as flooding, forest fires, and LOTS OF SNOW are concerns. The book's greatest strengths are its descriptions of nature, and how complicated a "simple" life can really be, with all the adjustments you have to make.

Still, it's beautiful, even if it's tough, and even if the soul-searching starts to get a bit wearying (it didn't for me, but I could see it happening), it's a good read for folks who like "people vs nature" and "what the hell should I do with my life?" as themes. Recommended for medium to large libraries, esp. in the Pacific Northwest. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Lin

Oct 19, 2017Lin rated it really liked it

Looking for a book to peacefully settle into? Iris Graville's Hiking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance, then, is your perfect companion.

Finding only stress and unanswered questions after 20 years in nursing, she convinces her husband and 13-year old twins to make a bold move -- to literally move the family from Bellingham to the remote community of Stehekin at the far northwest end of Lake Chelan where there are 85 year-round residents. The village is accessible only by a ferry, float plane, or a long hike.

What follows is a peacefully unfolding journey of discovery. She questions whether she has "stayed in nursing because it serves my own need to feel valued rather than out of compassion for those I care for?" Couple that with new-found solitude and unforeseen realities such as a forest fire that threatens the entire village, ordering groceries by U.S. Mail to be delivered a few days later by boat, and a snowfall that is measured in feet.

Described as a blend of Cheryl Strayed’s Wild and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Graville’s memoir chronicles her spiritual search for meaningful work as she lands a job at the local bakery, gently urging dough into delicious treats for villagers and tourists. She pursues a life-long interest in writing and finds time to just "be."

Her book should come with its own quilt to wrap up in while reading. Oh, wait...it is its own quilt, comforting and comfortable. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Jan Crossen

Sep 17, 2017Jan Crossen rated it it was amazing

Author, Iris Graville, bares her soul in this memoir. Iris was a successful wife and mother of twins, juggling a hectic career in public health, when she hit a major life roadblock. Her passion for nursing, the career she had worked so hard to perfect, had fizzled. Iris suffered from a nearly terminal case of professional ‘burn out.” Searching for answers and spiritual guidance as to her life’s purpose, she and her family moved to an extremely remote community. The family members agreed to experience the peace and solitude of a simple, less encumbered life for two years. Iris and her family grow and evolve as they overcome challenges with grit and determination. Iris is a talented and beautiful writer. She is a master of descriptions and has perfected the art of word selection. She uses humor, honesty and wit to share her journey of discovery in this inspirational story. I celebrated her victories and shared her tears of loss. Iris has found her calling, and thrives in her chosen vocation, community, and spiritual path. I highly recommend this book!

(less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Pat

Sep 16, 2019Pat rated it it was amazing

I actually picked up two books about Quakerism, this one and another by Phillip Gulley the author of the Harmony series. He is a Quaker minister so I figured he knows what he is talking about. But this book was the first one I was going to skim thru before I sat down to read. Just skimming made me stop and start reading instantly. I was sucked into the story and loved every moment of it.

Iris is having doubts about the direction her life is taking. Her husband is super understanding and even her kids get onboard when they decide to pack up their lives and move to a very remote area in Washington. What was suppose to be a one year experience turns into a two year life change. Everyone gets so much out of their time there so I think it was life changing for the entire family.

I just loved this book. I have recommended it to a couple friends already and really hope they give it a chance. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Heidi Barr

Aug 13, 2017Heidi Barr rated it it was amazing

I loved this book. Reading about the author's time living in a remote village made me reflect on my own choices, reminded me that community is essential for a full life, and reassured me that even though the human experience is peppered with loss, pain, and uncertainty, when it is grounded in nature and steeped in faith, any storm can be weathered. Taking stock of one’s life choices while raising a family can leave one feeling bare to the bone, and Iris tells her story with grace, humor, and humility. Highly recommended. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Barb

Sep 27, 2018Barb rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

A story by a Quaker about getting away from our “typical” US life of consumerism and living closer to nature and in community? Yes please. Iris did a terrific job describing her life in this removed community, how it affected her family, and ultimately how it really didn’t make her discernment that much easier or clearer. Enjoyed this very much.

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Sarah Ewald

Jul 11, 2018Sarah Ewald rated it really liked it

I was a bit taken aback by the title. In fact, someone saw it on my coffee table, and laughed. This is memoir by Iris Graville, who, like many, had become fed up with her job as a public health administrator. She started out as a nurse, which she loved, and over the years graduated into administration. Not always what it seems, she wanted something different. She quit her job and convinced her husband, Jerry, and 13 year old twins, to move to Stehekin, a remote mountain village in Washington state in the Northern Cascade Mountains. Seeking adventure and solitude, they researched their move and landed in a community of 85 residents, and a completely new reality, where they thrived. Kids took classes in a one-room school, Jerry drove transportation for a summer adventure resort and did odd jobs, and Iris took a job at the local bakery. Telephoning someone meant going into town to use the community phone by the dock; groceries came by boat (after having been 'mail-ordered'); forest fires were a reality, and floods could leave you stranded. Despite that, there were hikes to peaks and views seen by few, adventures of white water rafting, and moments of solitude in a cathedral of trees. Sounds like heaven to me.

I tried to figure out the title, and I came up with the vulnerabilities you experience when all conveniences are stripped away, and you become one with your small community. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Jennifer

Aug 30, 2018Jennifer rated it really liked it

Shelves: bookgroup

This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. To view it, click here. I was not sure what to expect from this book - I give it a high rating because a lot of what the author was going through sounded like me - I quit my job 3 yrs ago to try to figure out what to do...now I find myself still doing a little bit of it on the side. I, too, wanted less of a rat race of 'career advancement' - but I did not go quite so extreme as move nearly off the grid!

Also makes me wonder if I would have been a good Quaker. Meeting to sit in silence for an hour sounds better than many of the sermons I've heard in my lifetime. And sounds a lot like meditation. Plus, their activism has historically been amazing -several suffrage and abolitionist leaders were Quakers, for example.

Since the book was written (or at least published) 20+ years after they embarked on adventure - it was interesting to see how she returned a bit - was still doing some health consulting, they moved to Lopez (and remain there), her husband did return to his teaching career, too. I wonder if their experience would be the same (how has the town of Stehekin changed?) with the internet, wi-fi, cell phones, etc. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Heather Durham

Apr 30, 2019Heather Durham rated it it was amazing

Shelves: nonfiction, personal-essay-and-memoir

Iris Graville recently wrote an article for Brevity’s Nonfiction Blog on Writing the Quotidian, on the beauty and resonance to be found in everyday life. And that’s exactly what she explores in Hiking Naked, it’s just that her stories of work, family, friendship, interpersonal challenges, life and death just happen to take place in a remote village only accessible by boat, trail, or seaplane, where the everyday also might include bears in the yard, days without power, a flood that leaves you stranded, and literal and figurative nudity. In this beautiful memoir, Graville takes us with her as she experiences real life in the wilderness beyond the romantic honeymoon period in paradise. With a balance of levity and depth, contemplation and questioning, Hiking Naked may inspire you to reexamine your own choices, and to ponder the difference between seeking and escape.

(less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Claire

Jan 05, 2018Claire rated it it was amazing

Author Iris Graville's love for her family, her community, and the North Cascades wilderness shines through every page of this thoughtful memoir. In making the choice to be unplugged in the wilderness in the modern age, the Graville family discovers more joy, and more hardship, than they bargained for. Through fire and flood, deep snow and "roof-alanches," Graville and her husband and two children face it all with admirable openness and strength. In the practice of her Quaker faith, Graville allows the spirit lead her where it may, through ups and downs and logistics galore, in the end discovering a physical sense of place, and a creative, spiritual interior life as well. A unique, insightful journey. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Gloria

Jan 23, 2018Gloria rated it liked it

Shelves: for-the-spirit

Decent recounting of one woman's experience in stepping away from a frenetic lifestyle and living alternatively in a remote region of Washington state. Graville tells of her stressful nursing career as well as some family stressors. She is very open about financial concerns, family opinions, spiritual considerations, and just the cultural change of living in a seriously different environment.

This is not gripping in any way, but rather meanders through her thought process and the practical steps the family took to make this change. She seems like any middle-class mother and professional woman who recognizes being overwhelmed and is thinking out of the box to remedy the situation. (less)

==========

HIking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance and over 1.5 million other books are available for Amazon Kindle . Learn more

Books›Religion & Spirituality›Christian Books & Bibles

Included with a Kindle Unlimited membership

Read with Kindle Unlimited

$25.25

Prime FREE Delivery

Temporarily out of stock.

Order now and we'll deliver when available. We'll e-mail you with an estimated delivery date as soon as we have more information. Your account will only be charged when we ship the item.

Ships from and sold by Amazon AU.

Quantity:

1

Add to Cart

Buy Now

Deliver to Sejin - Campbelltown 5074

Add to Wish List

Add to Baby Wishlist

Share <Embed>

Other Sellers on Amazon

11 New from $25.25

See all 2 images

Follow the Author

Iris Graville

+ Follow

Hiking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance Paperback – Illustrated, 19 September 2017

by Iris Graville (Author)

4.4 out of 5 stars 13 ratings

See all formats and editions

Kindle

$0.00

This title and over 1 million more available with Kindle Unlimited

$3.99 to buy

Paperback

$25.25

11 New from $25.25

Free delivery for prime members

Read more

Save on selected Penguin Classics and Popular Penguin books.

View our selection and latest deals. Click to explore.

Customers who bought this item also bought

H is for Hawk (The Birds and the Bees)

H is for Hawk (The Birds and the Bees)

Helen MacdonaldHelen Macdonald

4.2 out of 5 stars 3,245

Paperback

$19.25

FREE Delivery

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Naked Hiking: Naked Hiking Essays from Around the World

Naked Hiking: Naked Hiking Essays from Around the World

Richard FoleyRichard Foley

4.7 out of 5 stars 11

Paperback

$34.10

Prime FREE Delivery

Temporarily out of stock.Temporarily out of stock.

Start reading HIking Naked: A Quaker Woman's Search for Balance on your Kindle in under a minute.

Don't have a Kindle? Get your Kindle here, or download a FREE Kindle Reading App.

Save up to 50% off RRP on select top books

PLUS, free expedited delivery. T&C's apply. See more

Product details

Publisher : Homebound Publications; Illustrated edition (19 September 2017)

Language : English

Paperback : 262 pages

ISBN-10 : 1938846842

ISBN-13 : 978-1938846847

Dimensions : 13.97 x 2.03 x 21.59 cm

Customer Reviews: 4.4 out of 5 stars 13 ratings

Product description

Review

"Hiking Naked shows us the possibilities that appear if we take the risk." -- Margery Post Abbott, author of To Be Broken and Tender

"This memoir of 'seeking, not escaping' speaks to the hearts of those longing to be free from modern constraints--work, money, ambition, stress of all sorts--to find their bliss, wherever it might be. For Graville, in 1993, that means listening to the urgings of her heart and leaving her job as a public health nurse in Bellingham, WA, and moving her family to Stehekin, a remote village near North Cascades National Park. What resonates throughout is her deep connection to Quakerism; here a gentle, quiet spirituality that encourages places and periods of silence rather than imposing rigid external demands. As her husband and children agree to this experiment, over the two years, all come in their own way to say, 'I thought I knew about powerlessness, ' only to find that the rigors of living life simply require letting go of much more than they ever could have imagined. Graville concludes that 'Far from feeling deprived, we found over and over again the riches of attending to what's truly important.' VERDICT: Reading this expressive and beautifully written memoir is to experience one's own quest toward self-discovery." -- Library Journal, *Starred Review!

About the Author

Iris Graville is the author of Hands at Work: Portraits and Profiles of People Who Work with Their Hands, recipient of numerous accolades including a Nautilus Gold Book Award, and BOUNTY: Lopez Island Farmers, Food, and Community. She also serves as publisher of SHARK REEF Literary Magazine. Iris lives and writes on Lopez Island, Washington.

How would you rate your experience shopping for books on Amazon today

Very poor Neutral Great

Customer reviews

4.4 out of 5 stars

4.4 out of 5

13 global ratings

5 star

64%

4 star

10%

3 star

26%

2 star 0% (0%)

0%

1 star 0% (0%)

0%

How are ratings calculated?

Review this product

Share your thoughts with other customers

Write a customer review

Top reviews

Top reviews

Top reviews from Australia

There are 0 reviews and 0 ratings from Australia

Top reviews from other countries

Lynda Bennion

3.0 out of 5 stars Not what I expected.

Reviewed in Canada on 5 December 2020

Verified Purchase

I was less than intrigued with this story. The book seemed to be based more on the author's trials and tribulations of her career choices more than the 'magic' of living a different life style in the boonies. I wanted to be charmed and enthralled with more grit about living 'off grid' per se.

Report abuse

Freeman

4.0 out of 5 stars Clean mountain air and a calm Quaker mind.

Reviewed in the United States on 1 November 2017

Verified Purchase

This thoughtful quiet book is filled with the scent of pine trees, ceanothus and baking bread, the sparkle of sunlight on blue mountain water, the busy hum of squabbling teenagers, the bustle of family and visitors coming and going, the taste of homemade pizza and the comfort of a steaming cup of mint tea. Above all it is a book about the sustaining comfort and richness of a happy and loving marriage, and how deep love and compassion can allow a couple to support each other as they change and grow as individuals. I enjoyed reading about places I’ve also been and lived, about Quakers, and about a family negotiating changes in their lives with skill, grace and good humor.

5 people found this helpful

Report abuse

Elaine

5.0 out of 5 stars Beautifully Written and Inspiring

Reviewed in the United States on 16 October 2017

Verified Purchase

Disconnect the wifi router, put your cell phone on “do not disturb” and read Iris Graville’s memoir “Hiking Naked”. This is the story of one woman listening to the still small voice within and following her leading to leave a successful career and spend 2 years with her family in an isolated mountain town in Washington State. One satellite phone connects the entire Stehekin village to the outside world. Yet, there is a warm and lively community of hearty artists, talented bakers, resourceful nature lovers and even a “one room” school house in this “frozen in time” (forgive the pun) setting. Hiking Naked reads like sitting down with a good friend in front of a warm fire and finally hearing all the details of a heart felt adventure: including the inner deep struggle for meaning and purpose as well as the outer beauty and sheer magnificence and inspiration of the natural world. Iris Graville writes beautifully about both.

3 people found this helpful

Report abuse

KBSeely

5.0 out of 5 stars A Journey Worth Sharing

Reviewed in the United States on 21 December 2017

Verified Purchase

I loved this book! If you’ve ever fantasized about stepping out of a life you’ve outgrown and trying a new one, Graville’s story about the leap she and her family took moving to a small isolated community in the North Cascades will transport you there. What a pleasure to spend time with them as they adapt to the simple pleasures – and new challenges – of living in tiny Stehekin, WA. Graville’s clear prose and thoughtful voice hooked me from page one; reading her book is like sitting down with a wise friend.

One person found this helpful

Report abuse

Aliopa

5.0 out of 5 stars Inspiring and beautifully written

Reviewed in the United States on 30 August 2018

Verified Purchase

I loved this book! Iris writes beautifully about leaving a fast-paced and stressful life in te city and moving to a remote village among the nature. She shares the practical aspects of the experience but also her inner 'work' to achieve a more balanced life. This book is definitely inspiring for anyone who is dissatisfied with modern life and wishes to live a slower and more meaningful life.

Report abuse