| |

학자 정보 | |

| 출생 | 1874년 3월 6일 Obukhiv, 키이우 |

| 사망 | 1948년 3월 24일 클라마르 |

| 국적 | 프랑스 러시아 제국 소련 러시아 공화국 러시아 소비에트 연방 사회주의 공화국 바이마르 공화국 |

| 학력 | 키예프 대학교 |

| 부모 | Alexandre Michailovitch Berdiaev(부) Alina Sergeevna Kudasheva(모) |

| 배우자 | Lydia Yudifovna Berdyaev |

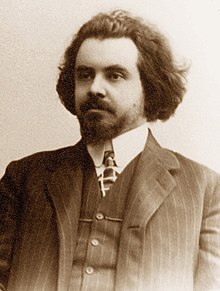

니콜라이 알렉산드로비치 베르댜예프(러시아어: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев, 1874년 3월 18일 ~ 1948년 3월 24일)는 러시아의 사상가이다.

소개

[편집]1874년에 오늘날 우크라이나의 수도인 키예프에서 태어났다. 그의 가문은 전통적으로 군인을 배출해 왔기 때문에, 그도 유년 시절 사관학교에서 군인 교육을 받았다. 그렇지만 어린 시절부터 인문학적 주제에 관심을 가지고 있던 베르댜예프는 부모의 허락을 받아 사관학교 생활을 중단하고 키예프대학 법학부에서 공부하게 되었다. 그가 대학생활을 하던 1890년대는 러시아의 역사적 진로를 놓고 인민주의자들과 마르크스주의자들 사이에 일대 사상적인 대결이 벌어지고 있었다. 이때 베르댜예프는 마르크스주의 운동에 가담하여 반정부 투쟁을 벌이다가 체포되어 볼로그다에서 유형 생활을 하게 되었다. 그렇지만 그는 곧 유물론적인 마르크스주의를 비판하면서, 기독교를 기반으로 한 독창적인 사상을 발전시켜 나가게 되었다. 특히 그의 사상은 인격이 지닌 자유의 중요성을 강조하였다. 그리하여 그는 마르크스주의자들의 극단성과 파괴성을 우려하면서, 1917년에 발발하게 될 러시아 혁명의 성격을 예견하였다. ≪인텔리겐치아의 정신적 위기≫, ≪자유의 철학≫, ≪창조의 의미, 인간의 정당화 경험≫과 같은 책들은 바로 베르댜예프의 이런 사상의 초석을 놓은 저서들이었다.

베르댜예프는 학문적인 명성 덕분에 러시아 혁명 직후인 1920년에는 모스크바대학에 교수로 초빙되기도 하였다. 그러나 소비에트 정권은 사회주의 건설에 걸림돌이 될까 우려하여 일군의 지성인들과 함께 그를 국외로 추방하고 말았다. 그는 그 이후에 베를린과 파리에서 종교철학 아카데미를 설립하여 활발한 강연 활동과 저술 활동을 하게 되었다. 그는 추방 시기에 자유와 인격에 대한 해석을 역사철학적으로 더욱 정교하게 가다듬었다. 그리하여 ≪역사의 의미≫, ≪새로운 중세≫, ≪러시아의 이념≫, ≪러시아 공산주의의 기원과 의미≫ 등과 같은 명저들이 출간되어 나오게 되었다.

현대 세계의 인간 운명

[편집]《현대 세계의 인간 운명》은 1934년에 출간된 베르댜예프의 대표작 중 하나로서, 현대의 성격을 면밀하게 분석한 결과물이라고 말할 수 있다. 여기서 베르댜예프는 스탈린 치하의 소련 공산주의, 히틀러 치하의 독일 파시즘 체제, 그리고 서구의 자유주의 체제를 독특한 관점에서 해석하였다. 그에 따르자면, 이 세 체제는 얼핏 보면 서로 간에 적대적인 태도를 보이는 것 같지만, 사실 비인간화라는 점에서는 공통점을 가지고 있었다. 왜냐하면 이런 체제들은 폭력적인 방식으로나 자본의 힘을 가지고 하나같이 인격의 자유를 억압하고 있기 때문이다. 베르댜예프는 이런 상황을 극복하기 위한 길을 기독교에 근거를 둔 영적 능력의 계발을 통해서 찾고자 하였다. 그렇지만 베르댜예프는 현상으로서의 기독교 조직에는 그다지 만족하지 않았다. 그것은 물질주의, 초월적인 이기주의 등에 물들어 있어서 진정한 기독교적 사명을 담당할 수 없었다. 따라서 그는 기독교가 편협성을 버리고 사랑과 자유에 대한 올바른 관점을 회복함으로써만 이런 일을 감당할 수 있다고 보았다.

베르댜예프는 러시아에 수립된 공산주의 정권만이 아니라 이탈리아에서 새롭게 등장하고 있던 파시즘, 그리고 1930년대 초에 독일의 집권 세력이 된 국가사회주의를 주목하면서 자신의 역사철학적 관점을 더욱 발전시켜나갔다. 그 결과 베르댜예프의 역사철학을 담은 대표적인 저술인 ≪현대 세계의 인간 운명≫이 1934년에 출간되었다. ‘자유의 포로’라는 별칭을 지닌 베르댜예프 사상의 핵심 개념은 ‘자유’와 ‘인격’이라고 볼 수 있는데, 이 책에서 이 두 개념은 제1차 세계대전 이후의 세계를 대상으로 한 역사철학적 관점에서 조명되고 있다.

베르댜예프가 보기에, 인간은 바로 신의 형상(образ)과 모양(подобие)으로 만들어진 인격적 존재였다. 그가 말하는 인격(personality)은 내적인 중심을 갖춘 통합적인 존재로서의 인간의 참모습을 말하는 것으로서, 실존주의 철학자들이 말하는 ‘실존(existence)’과는 다른 것이었다. 흔히 20세기 최고의 철학자로 일컬어지는 하이데거가 “던져져 있으면서 앞으로 내던지는(geworfener Entwurf)” 실존을 말했다면, 베르댜예프는 이러한 하이데거의 철학에서 ‘절망의 철학이자 절대적인 비관론’의 모습을 보았다. 베르댜예프는 종종 기독교 실존주의 철학자라고 불리기도 하지만, 사실 그는 실존주의 철학의 범주에 머물러 있지는 않았다. 그는 막스 셸러(Max Scheler)나 자크 마리탱(Jacques Maritain)과 같은 세계적인 철학자들과 교유하면서, 실존주의 철학을 넘어선 독특한 ‘인격주의’ 철학을 발전시켰다는 평가를 받고 있다.

베르댜예프에 따르자면, 인격은 신의 형상을 닮은 모습이면서도 자유를 그 본질로 삼고 있었다. 여기서 그가 말하는 자유는 정치적인 차원이나 사회경제적인 차원으로 국한될 수 없는 인간 정신의 영원한 근거였다. 이 책에서도 잘 설명되어 있듯이, 소련에서 성립된 공산주의 체제라든지 이탈리아에서 성립된 파시즘 체제라든지 독일에서 성립된 히틀러의 국가사회주의 체제는 하나같이 인격의 자유를 억누르는 집단주의의 산물로서 심지어 광기에 사로잡힌 형태라고도 볼 수 있었다.

베르댜예프는 ≪현대 세계의 인간 운명≫에서 공산주의와 파시즘, 그리고 국가사회주의만 비판하고 있는 것이 아니다. 그는 소위 ‘경제적 자유’가 보장되고 있다고 자부하고 있는 자본주의적 의회민주주의 체제의 문제점도 예리하게 파고들고 있다. 실업 문제 등에서 드러나는 것처럼, 익명화된 자본주의는 ‘생산이 인간을 위해서 존재하는 것이 아니라 인간이 생산을 위해서 존재하는’ 결과를 낳았다. 베르댜예프의 냉정한 평가에 따르자면, 현대의 기술 발전으로 인하여 인간은 기계에 예속되어 전일성(全一性)을 상실하고 파편화되어 버렸다.

베르댜예프가 ≪현대 세계의 인간 운명≫에서 바라본 인간의 운명은 이처럼 심각한 위기에 처해 있었다. 20세기 전반의 실존주의 철학자들도 베르댜예프처럼 현대 사회에서 인간이 집단의 한 단위이자 하나의 기계 부품으로 비인간화되어 가는 모습을 지적했다. 그렇지만 막연한 방식으로 불안의 극복을 외쳤던 실존주의와는 달리, 베르댜예프는 현대 사회 인간이 처한 위기의 탈출 방법도 제시하고 있다. 그것은 바로 문제의 근원인 인격을 회복하는 것이다. 베르댜예프는 이러한 길을 인격과 공동체의 원칙을 결합시키는 ‘인격주의적인 사회주의’라고 부르고 있다.

- 조호연 역, 지만지, ISBN 978-89-6680-350-7

저서 목록

[편집]- 1901 주체와 공동체의 철학 - 김규영 역

- 1939 노예냐 자유냐 - 이신 역 | 늘봄출판사

- 1941 도스토옙스키의 세계관 - 이종진 역 | HUINE

- 1957 현대 세계의 인간 운명 - 조호연 역 | 지만지

- 1933 인간과 기계 - 안성헌 역 | 대장간

같이 보기

[편집]외부 링크

[편집] 위키미디어 공용에 니콜라이 베르댜예프 관련 미디어 분류가 있습니다.

위키미디어 공용에 니콜라이 베르댜예프 관련 미디어 분류가 있습니다.

Nikolai Berdyaev

Nikolai Berdyaev | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev 18 March 1874 |

| Died | 24 March 1948 (aged 74) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy |

| School | Christian existentialism, personalism |

Main interests | Creativity, eschatology, freedom |

Notable ideas | Emphasizing the existential spiritual significance of human freedom and the human person |

Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev (/bərˈdjɑːjɛf, -jɛv/;[1] Russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев; 18 March [O.S. 6 March] 1874 – 24 March 1948) was a Russian philosopher, theologian, and Christian existentialist who emphasized the existential spiritual significance of human freedom and the human person. Alternative historical spellings of his surname in English include "Berdiaev" and "Berdiaeff", and of his given name "Nicolas" and "Nicholas".

Biography

[edit]Nikolai Berdyaev was born near Kiev in 1874 to an aristocratic military family.[2] His father, Alexander Mikhailovich Berdyaev, came from a long line of Russian nobility. Almost all of Alexander Mikhailovich's ancestors served as high-ranking military officers, but In the sixth grade, he left the cadet school and began studying for the matriculation exams for admission to the university. Nikolai's mother, Alina Sergeevna Berdyaeva, was half-French and came from the top levels of both French and Russian nobility. She also had Polish and Tatar origins.[3][4]

Berdyaev decided on an intellectual career and entered the Kiev University in 1894. It was a time of revolutionary fervor among the students and the intelligentsia. He became a Marxist for a period and was arrested in a student demonstration and expelled from the university. His involvement in illegal activities led in 1897 to three years of internal exile to Vologda in northern Russia.[5]: 28

Social activities

[edit]In 1899, his first article "F. A. Lange and Critical Philosophy in their relation to Socialism" was published in the magazine "Die Neue Zeit".

In the following years, before his expulsion from the USSR in 1922, Berdyaev wrote numerous articles and several books, of which, according to him, he later truly appreciated only two — "The Meaning of Creativity" and "The Meaning of History."

A fiery 1913 article, entitled "Quenchers of the Spirit", criticising the rough purging of Imiaslavie Russian monks on Mount Athos by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church using tsarist troops, caused him to be charged with the crime of blasphemy, the punishment for which was exile to Siberia for life. The World War and the Bolshevik Revolution prevented the matter coming to trial.[6]

Berdyaev's disaffection culminated, in 1919, with the foundation of his own private academy, the "Free Academy of Spiritual Culture". It was primarily a forum for him to lecture on the hot topics of the day and to present them from a Christian point of view. He also presented his opinions in public lectures, and every Tuesday, the academy hosted a meeting at his home because official Soviet anti-religious activity was intense at the time and the official policy of the Bolshevik government, with its Soviet anti-religious legislation, strongly promoted state atheism.[5]

In 1920, Berdiaev became professor of philosophy at the University of Moscow. In the same year, he was accused of participating in a conspiracy against the government; he was arrested and jailed. Felix Dzerzhinsky, the feared head of the Cheka, personally interrogated him,[7]: 130 and he gave his interrogator a solid dressing down on the problems with Bolshevism.[5]: 32 Novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his book The Gulag Archipelago recounts the incident as follows:

After his expulsion from the USSR on September 29, 1922, on the so—called "Philosophers' ships", Berdyaev and other émigrés went to Berlin, where he founded an academy of philosophy and religion, but economic and political conditions in the Weimar Republic caused him and his wife to move to Paris in 1923. He transferred his academy there, and taught, lectured and wrote, working for an exchange of ideas with the French and European intellectual community, and participated in a number of international conferences.[9]

Philosophical work

[edit]According to Marko Marković, Berdyaev "was an ardent man, rebellious to all authority, an independent and "negative" spirit. He could assert himself only in negation and could not hear any assertion without immediately negating it, to such an extent that he would even be able to contradict himself and to attack people who shared his own prior opinions".[5] According to Marina Makienko, Anna Panamaryova, and Andrey Gurban, Berdyaev's works are "emotional, controversial, bombastic, affective and dogmatic".[10]: 20 They summarise that, according to Berdyaev, "man unites two worlds – the world of the divine and the natural world. ... Through the freedom and creativity the two natures must unite... To overcome the dualism of existence is possible only through creativity.[10]: 20

David Bonner Richardson described Berdyaev's philosophy as Christian existentialism and personalism.[11] Other authors, such as political theologian Tsoncho Tsonchev, interpret Berdyaev as "communitarian personalist" and Slavophile. According to Tsonchev, Berdyaev's philosophical thought rests on four "pillars": freedom, creativity, person, and communion.[12]

One of the central themes of Berdyaev's work was philosophy of love.[13]: 11 At first he systematically developed his theory of love in a special article published in the journal Pereval (Russian: Перевал) in 1907.[13] Then he gave gender issues a notable place in his book The Meaning of the Creative Act (1916).[13] According to him, 1) erotic energy is an eternal source of creativity, 2) eroticism is linked to beauty, and eros means search for the beautiful.[13]: 11

He also published works about Russian history and the Russian national character. In particular, he wrote about Russian nationalism:[14]

Though sometimes quoted as a Christian anarchist for his emphasis on theology and critique of statist and Marxist socialism, Berdyaev did not self-identify as such and differentiated himself from Leo Tolstoy.[15]

Nikolai Berdyaev's work is also featured in the dedication of Aldous Huxley's 1932 novel "Brave New World".

Theology and relations with Russian Orthodox Church

[edit]Berdyaev was a member of the Russian Orthodox Church,[16][17] and believed Orthodoxy was the religious tradition closest to early Christianity.[18]: at unk.

Nicholas Berdyaev was an Orthodox Christian, however, it must be said that he was an independent and somewhat a "liberal" kind. Berdyaev also criticized the Russian Orthodox Church and described his views as anticlerical.[6] Yet he considered himself closer to Orthodoxy than either Catholicism or Protestantism. According to him, "I can not call myself a typical Orthodox of any kind; but Orthodoxy was near to me (and I hope I am nearer to Orthodoxy) than either Catholicism or Protestantism. I never severed my link with the Orthodox Church, although confessional self-satisfaction and exclusiveness are alien to me."[16]

Berdyaev is frequently presented as one of the important Russian Orthodox thinkers of the 20th century.[19][20][21] However, neopatristic scholars such as Florovsky have questioned whether his philosophy is essentially Orthodox in character, and emphasize his western influences.[22] But Florovsky was savaged in a 1937 Journal Put' article by Berdyaev.[23] Paul Valliere has pointed out the sociological factors and global trends which have shaped the Neopatristic movement, and questions their claim that Berdyaev and Vladimir Solovyov are somehow less authentically Orthodox.[20]

Berdyaev affirmed universal salvation, as did several other important Orthodox theologians of the 20th century.[24] Along with Sergei Bulgakov, he was instrumental in bringing renewed attention to the Orthodox doctrine of apokatastasis, which had largely been neglected since it was expounded by Maximus the Confessor in the seventh century,[25] although he rejected Origen's articulation of this doctrine.[26][27]

The aftermath of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, along with Soviet efforts towards the separation of church and state, caused the Russian Orthodox émigré diaspora to splinter into three Russian Church jurisdictions: the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (separated from Moscow Patriarchate until 2007), the parishes under Metropolitan Eulogius (Georgiyevsky) that went under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, and parishes that remained under the Moscow Patriarchate. Berdyaev was among those that chose to remain under the omophorion of the Moscow Patriarchate. He is mentioned by name on the Korsun/Chersonese Diocesan history as among those noted figures who supported the Moscow Patriarchate West-European Eparchy (in France now Korsun eparchy).[28]

Currently, the house in Clamart in which Berdyaev lived, now comprises a small "Berdiaev-museum" and attached Chapel in name of the Holy Spirit,[29] under the omophorion of the Moscow Patriarchate. On 24 March 2018, the 70th anniversary of Berdyaev's death, the priest of the Chapel served panikhida-memorial prayer at the Diocesan cathedral for eternal memory of Berdyaev,[30] and later that day the Diocesan bishop Nestor (Sirotenko) presided over prayer at the grave of Berdyaev.[31]

Works

[edit]

In 1901 Berdyaev opened his literary career so to speak by work on Subjectivism and Individualism in Social Philosophy. In it, he analyzed a movement then beginning in Imperial Russia that "at the beginning of the twentieth-century Russian Marxism split up; the more cultured Russian Marxists went through a spiritual crisis and became founders of an idealist and religious movement, while the majority began to prepare the advent of Communism". He wrote "over twenty books and dozens of articles."[32]

The first date is of the Russian edition, the second date is of the first English edition.

- Subjectivism and Individualism in Societal Philosophy (1901)

- The New Religious Consciousness and Society (1907) (Russian: Новое религиозное сознание и общественность, romanized: Novoe religioznoe coznanie i obschestvennost, includes chapter VI "The Metaphysics of Sex and Love")[33]

- Sub specie aeternitatis: Articles Philosophic, Social and Literary (1900–1906) (1907; 2019) ISBN 9780999197929 ISBN 9780999197936

- Vekhi – Landmarks (1909; 1994) ISBN 9781563243912

- The Spiritual Crisis of the Intelligentsia (1910; 2014) ISBN 978-0-9963992-1-0

- The Philosophy of Freedom (1911; 2020) ISBN 9780999197943 ISBN 9780999197950

- Aleksei Stepanovich Khomyakov (1912; 2017) ISBN 9780996399258 ISBN 9780999197912

- "Quenchers of the Spirit" (1913; 1999)

- The Meaning of the Creative Act (1916; 1955) ISBN 978-15973126-2-2

- The Crisis of Art (1918; 2018) ISBN 9780996399296 ISBN 9780999197905

- The Fate of Russia (1918; 2016) ISBN 9780996399241

- Dostoevsky: An Interpretation (1921; 1934) ISBN 978-15973126-1-5

- Oswald Spengler and the Decline of Europe (1922)

- The Meaning of History (1923; 1936) ISBN 978-14128049-7-4

- The Philosophy of Inequality (1923; 2015) ISBN 978-0-9963992-0-3

- The End of Our Time [a.k.a. The New Middle Ages] (1924; 1933) ISBN 978-15973126-5-3

- Leontiev (1926; 1940)

- Freedom and the Spirit (1927–8; 1935) ISBN 978-15973126-0-8

- The Russian Revolution (1931; anthology)

- The Destiny of Man (1931; translated by Natalie Duddington 1937) ISBN 978-15973125-6-1

- Lev Shestov and Kierkegaard N. A. Beryaev 1936

- Christianity and Class War (1931; 1933)

- The Fate of Man in the Modern World (1934; 1935)

- Solitude and Society (1934; 1938) ISBN 978-15973125-5-4

- The Bourgeois Mind (1934; anthology)

- The Origin of Russian Communism (1937; 1955)

- Christianity and Anti-semitism (1938; 1952)

- Slavery and Freedom (1939) ISBN 978-15973126-6-0

- The Russian Idea (1946; 1947)

- Spirit and Reality (1946; 1957) ISBN 978-15973125-4-7

- The Beginning and the End (1947; 1952) ISBN 978-15973126-4-6

- Towards a New Epoch" (1949; anthology)

- Dream and Reality: An Essay in Autobiography (1949; 1950) alternate title: Self-Knowledge: An Essay in Autobiography ISBN 978-15973125-8-5

- The Realm of Spirit and the Realm of Caesar (1949; 1952)

- Divine and the Human (1949; 1952) ISBN 978-15973125-9-2

- "The Truth of Orthodoxy", Vestnik of the Russian West European Patriarchal Exarchate, translated by A.S. III, Paris, 1952, retrieved 27 September 2017

- Truth and Revelation (n.p.; 1953)

- Astride the Abyss of War and Revolutions: Articles 1914–1922 (n.p.; 2017) ISBN 9780996399272 ISBN 9780996399289

- Sources

- '"Bibliographie des Oeuvres de Nicolas Berdiaev" établie par Tamara Klépinine' published by the Institut d'études Slaves, Paris 1978

- Berdyaev Bibliography on www.cherbucto.net

- By-Berdyaev Online Articles Index

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Berdyaev" Archived 20 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Nicolaus, Georg (2011). "Chapter 2 "Berdyaev's life"" (PDF). C.G. Jung and Nikolai Berdyaev: Individuation and the Person: A Critical Comparison. Routledge. ISBN 9780415493154. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Young, George M. (2012) The Russian Cosmists: The Esoteric Futurism of Nikolai Fedorov and His Followers, Oxford University Press, p. 134. ISBN 978-0199892945

- ^ Berger, Stefan and Miller, Alexei (2015) Nationalizing Empires, Central European University Press, p. 312. ISBN 978-9633860168

- ^ a b c d Marko Marković, La Philosophie de l'inégalité et les idées politiques de Nicolas Berdiaev (Paris: Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1978).

- ^ a b Self-Knowledge: An Essay in Autobiography, by Nicolas Berdyaev (Author), Katharine Lampert (Translator), Boris Jakim (Foreword) ISBN 1597312584.

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (1973). "Chapter 3 The Interrogation". The Gulag Archipelago, 1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, I–II. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060803322.

- ^ Cited by Markovic, op. cit., p.33, footnote 36.

- ^ "A Conference in Austria". www.berdyaev.com. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b Makienko, Marina; Panamaryova, Anna; Gurban, Andrey (7 January 2015). "Special Understanding of Gender Issues in Russian Philosophy" (PDF). Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 166. Elsevier: 18–23. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.476.

- ^ Richardson, David Bonner (1968). "Existentialism: A Personalist Philosophy of History". Berdyaev's Philosophy of History. pp. 90–137. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-8870-8_3. ISBN 978-94-011-8210-2.

- ^ Tsonchev, Tsoncho (2021). Person and communion: the political theology of Nikolai Berdyaev. McGill University’s institutional digital repository: McGill University. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d Shestakov, Vyacheslav (1991). "Вступительная статья". In Шестаков, В.П. (ed.). Русский Эрос, или Философия любви в России [Russian Eros, Or Philosophy of Love in Russia] (in Russian). Progress Publishers. pp. 5–18. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Quoted from book by Benedikt Sarnov, Our Soviet Newspeak: A Short Encyclopedia of Real Socialism., pp. 446–447. Moscow: 2002, ISBN 5-85646-059-6 (Наш советский новояз. Маленькая энциклопедия реального социализма).

- ^ Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre (17 February 2022). Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel (Abridged ed.). Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-84540-663-9.

- ^ a b Witte, John; Alexander, Frank S. (2007). The Teachings of Modern Orthodox Christianity on Law, Politics, and Human Nature. Columbia University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-231-14265-6.

- ^ "Berdyaev, Orthodox religious philosopher, dies in Paris". The Living Church. Vol. 116. Morehouse-Gorham Company. 1948. p. 8.

a devout member of Russian Orthodox Church

- ^ Berdyaev 1952.

- ^ Noble, Ivana (2015). "Three Orthodox visions of ecumenism: Berdyaev, Bulgakov, Lossky". Communio Viatorum. 57 (2): 113–140. ISSN 0010-3713.

- ^ a b Valliere, Paul (2006). "Introduction to the Modern Orthodox Tradition". In Witte, John Jr.; Alexander, Frank S. (eds.). The Teachings of Modern Christianity on Law, Politics, and Human Nature. Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 2–4.

- ^ Clarke, Oliver Fielding (1950). Introduction to Berdyaev. Bles.

- ^ Florovsky, George (1950). "Book review: Introduction to Berdyaev By Clarke. Nicolas Berdyaev: Captive of freedom by Spinka". Church History. 19 (4): 305–306. doi:10.2307/3161171. JSTOR 3161171. S2CID 162966900.

- ^ "Ortodoksia and Humanness". www.berdyaev.com. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Cunningham, M.B.; Theokritoff, E. (2008). The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Christian Theology. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0521864848.

- ^ Blowers, Paul M. (2008). "Apokatastasis". In Benedetto, R.; Duke, J.O. (eds.). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras. New Westminster Dictionary Series. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-664-22416-5.

- ^ Deak, Esteban (1977). Apokatastasis: The Problem Of Universal Salvation In Twentieth Century Theology (Thesis). Toronto, Canada: University of St. Michael's College. pp. 20–60. ISBN 9780315454330.

- ^ Kirwan, Michael; Hidden, Sheelah Treflé (2016). Mimesis and Atonement: René Girard and the Doctrine of Salvation. Violence, Desire, and the Sacred. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-5013-2544-1.

- ^ "ИСТОРИЯ ЕПАРХИИ". Cerkov-ru.eu. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Часовня в честь Святого Духа в Кламаре". Cerkov-ru.eu. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Sheshko, Prêtre Georges. "Il y a 70 ans, Nicolas Berdiaev (1874–1948), célèbre philosophe russe, était rappelé à Dieu". Egliserusse.eu. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Исполнилось 70 лет со дня кончины известного русского философа Николая Бердяева". Cerkov-ru.eu. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Steeves, P.D. (2001) "Berdyaev, Nikolai Aleksandrovich (1874–1948)" in Walter A. Elwell, Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, Baker Academic, p. 149. ISBN 978-0801020759

- ^ The book is not available in English. For secondary literature in English, see:

- Crone, Anna Lisa (2010). Eros and Creativity in Russian Religious Renewal: The Philosophers and the Freudians. Russian History and Culture. Vol. 3. Netherlands: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004180055. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Naiman, Eric (1997). Sex in Public: The Incarnation of Early Soviet Ideology. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691026268. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Donald A. Lowrie. Rebellious Prophet: A Life of Nicolai Berdyaev. Harper & Brothers, New York, 1960.

- M. A. Vallon. An apostle of freedom: Life and teachings of Nicolas Berdyaev. Philosophical Library, New York, 1960.

- Lesley Chamberlain. Lenin's Private War: The Voyage of the Philosophy Steamer and the Exile of the Intelligentsia. St. Martin's Press, New York, 2007.

- Marko Marković, La Philosophie de l'inégalité et les idées politiques de Nicolas Berdiaev (Paris: Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1978).

Further reading

[edit]- Lossky, N.O. (1951). "Н.А. Бердяев" [N. Berdyaev]. История российской Философии [History of Russian Philosophy]. New York: International Universities Press Inc. ISBN 978-0-8236-8074-0.

- Nucho, Fuad (1967). Berdyaev's Philosophy: The existential paradox of freedom and necessity (1st ed.). London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

- Atterbury, Lyn (October 1978). "Nicholas Berdyaev, Orthodox nonconformist". Third Way. Toward a Biblical World View: 13–15. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Griffith, Jeremy (2013). Freedom Book 1. Vol. Part 4:7: Nikolai Berdyaev’s admission of the involvement of our moral instincts and corrupting intellect in producing the upset state of the human condition and attempt to explain how those elements produced that upset psychosis. WTM Publishing & Communications. ISBN 978-1-74129-011-0. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- Men', Fr. Aleksandr (2015). Russian Religious Philosophy: 1989–1990 Lectures [Русская религиозная философия: Лекции]. frsj Publications. ISBN 9780996399227.

- Sergeev, Mikhail (1994). "Post-Modern Themes in the Philosophy of Nicholas Berdyaev". Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. 14 (5). Retrieved 27 September 2017.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Nikolai Berdyaev at the Internet Archive

- Works by Nikolai Berdyaev at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Berdyaev Online Library and Index

- Dirk H. Kelder's collection of Berdyaev essays and quotes

- Philosopher of Freedom Archived 20 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ISFP Gallery of Russian Thinkers: Nikolay Berdyaev

- Nikolai Berdiaev and Spiritual Freedom

- Fr. Aleksandr Men' Lecture on N. A. Berdyaev

- Odinblago.ru: Бердяев Николай Александрович (Russian)

- Korsun/Chersonese Eparchy (Russian and French language)