BUSHIDO: WAY OF TOTAL BULLSHITEVERYTHING TOM CRUISE TAUGHT YOU ABOUT SAMURAI IS WRONG

The term bushido calls forth ghosts of Japan's hallowed samurai class. A class so bent on preserving honor, they'd rather slit their own bellies in ritualistic suicide than live a shamed existence.

In The Last Samurai, bushido melds with Nathan Algren's soul, curing the troubled American of alcoholism, war trauma, and self-loathing. What powerful medicine! A reinvigorated, purified Algren turns his back on his employers to join rebel samurai bent on defending bushido, their dignified honor-code of loyalty, benevolence, etiquette, and self-control.

At least, that's what popular culture would have us believe. In reality the term bushido went unrecognized until the early twentieth century, long after Nathan Algren's fictitious character joined the factual Satsuma Rebellion and years after the ousting of the samurai class. In all likelihood samurai never even uttered the word.

It may come as an even greater surprise that bushido once received more recognition abroad than in Japan. In 1900 writer Inazo Nitobe's published Bushido: The Soul of Japan in English, for the Western audience. Nitobe subverted fact for an idealized imagining of Japan's culture and past, infusing Japan's samurai class with Christian values in hopes of shaping Western interpretations of his country.

Though initially rejected in Japan, Nitobe's ideology would be embraced by a government driven war machine. Thanks to its empowering vision of the past, the extreme nationalist movement embraced bushido, exploiting The Soul of Japan to pave Japan's way to fascism in the buildup to World War II.

And so too The Last Samurai exploits Inazo Nitobe's depiction of bushido, renewing movie-going audiences' admiration for a venerable concept and glorified past that never truly existed. But as bushido's precarious history proves, the truth often takes a back seat to more fashionable depictions, whether it be to change Western perceptions, fuel a fascist war agenda, or sell movie tickets.

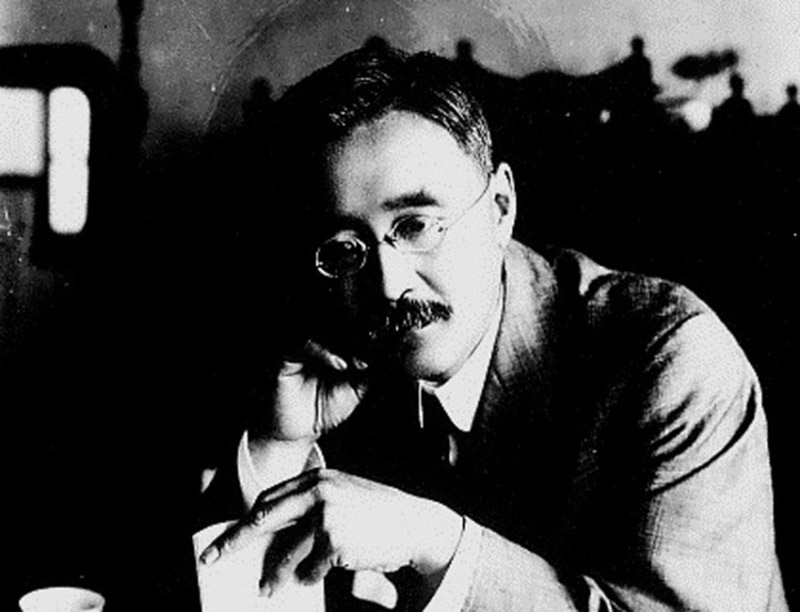

INAZO NITOBE

Born in 1862 in Iwate Prefecture, Inazo Nitobe was just a baby when the final remnants of Japan's ruling samurai class came to an end. Despite being of the samurai class themselves, Nitobe's family remained far removed from the battlefields and warrior culture of old Japan, gaining recognition as pioneers of irrigation and farming techniques.

At age nine Nitobe moved to Tokyo to live with his uncle where he began intensive English study. A unique subject of study at the time, Nitobe would become fluent in the language. In Death, Honor, and Loyalty: The Bushido Ideal, Cameron Hurst writes, "The Christian son of a late Tokugawa samurai… who was educated largely in English at special schools early in the Meiji era, Nitobe… could communicate with foreigners to a degree that even the most ardent exponents of kokusaika (internationalization) today would envy" (511).

In 1877 Nitobe made his way to Hokkaido where he enrolled in Sapporo Agricultural College. Created under the influence of William S. Clark, a devout Calvinist from New England, the school served to further solidify Nitobe's commitment to the Christian faith and he joined Clark's own "Sapporo Band" of Christians (Oshiro).

In Sapporo, Nitobe's estrangement from the Japanese society, culture and people grew. Japan's northernmost island remained largely unsettled wilderness and shared few cultural connections with mainland Japan. "Hokkaido was only just becoming a real part of Japan," Hurst writes, "so Nitobe was essentially isolated spatially, culturally, religiously, and even linguistically from the currents of Meiji Japan" (512).

Following his graduation from Sapporo Agricultural College, Nitobe began graduate school in Tokyo. Unsatisfied with his studies, in 1884 Nitobe moved to the United States and enrolled in John Hopkins University. After graduating, the globetrotting Nitobe would bounce around Germany, the United States and Sapporo and even become the under-secretary general of the League of Nations (Samuel Snipes).

Unique to his era, Nitobe's knowledge of English and Western literature remains impressive even by today's standards. Oleg Benesch, author of the in-depth study Bushido: The Creation of a Martial Ethic In Late Meiji Japan writes that Nitobe grew to be "more comfortable in English than Japanese" and eventually "lamented his lack of education in Japanese history and religion" (159).

It was during his time in California that Nitobe penned Bushido: The Soul of Japan. The contrived imagining of the samurai class reshaped Western perceptions of Japan and would eventually come to redefine Japan's own interpretation of bushido and the samurai class.

PLAYING CATCH-UP: THE MEJI RESTORATION

While Nitobe immersed himself in Western religion and culture, the Japanese government continued its own international pursuit – modernization. Professor Kenichi Ohno of GRIPS explains, "The top national priority was to catch up with the West in every aspect of civilization, i.e. to become a 'first-class nation' as quickly as possible" (43).

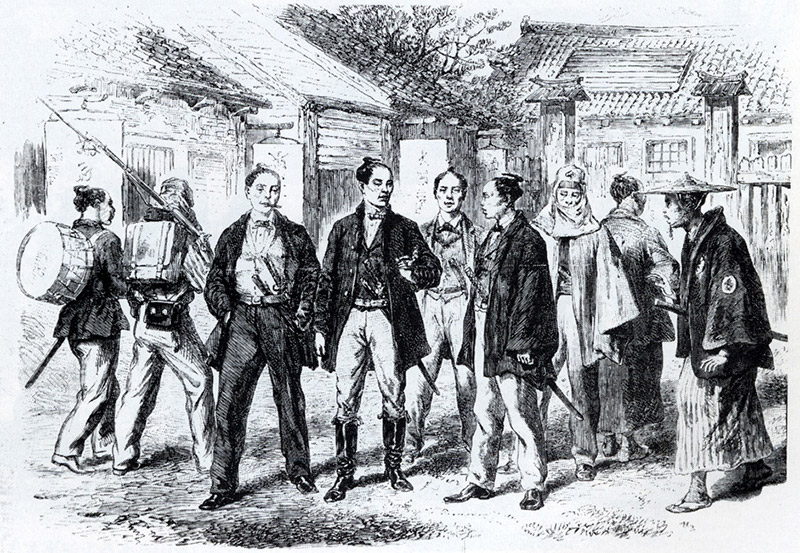

Years of isolationism meant Japan had fallen behind the world powers in terms of technology and military power. When Commodore Matthew Perry flexed his black ships' military muscle in the early 1850s, Japan had no alternative but to accept his terms. In professor Ohno's words, resulting exposure to foreign technology and culture "shattered their (Japan's) pride," making Japanese view their own nation as backward and out of step with the world (43).

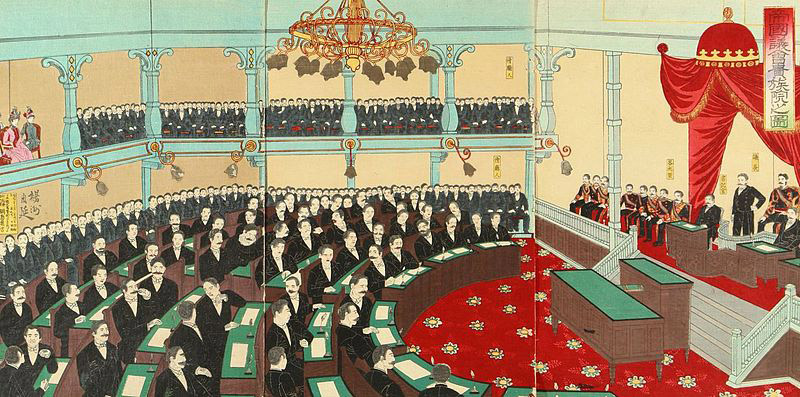

Japan's Meiji government looked to the West not to Westernize per se, but to become a powerful nation on the world stage. While Nitobe doted over Western culture, the Meiji government devised a three pronged plan for modernization that focused on "industrialization (economic modernization), introducing a national constitution and parliament (political modernization), and external expansion (military modernization)" (Ohno 18).

Political modernization would bring an end to Japan's feudal system and therefore its ruling samurai class. New policies stripped the samurai of privileges and blurred class separation. Voyages in World History explains:

The Meji reforms replaced the feudal domains of daimyo with regional prefectures under control of the central government. Tax collection was centralized to solidify the government's economic control… All the old distinctions between samurai and commoners were erased: 'The samurai abandoned their swords… and non-samurai were allowed to have surnames and ride horses.' The rice allowances on which samurai families had lived were replaced by modest cash stipends. Many former samurai had to face the indignity of looking for work. (686)

Meanwhile, by strengthening its military Japan sought to protect its interests and become a player on the world stage. And Japan's efforts saw quick results. Kenichi Ohno writes, "In the military arena, Japan won a war against China in 1894-95 and began to invade Korea (it was later colonized in 1910). Japan also fought a victorious war with the Russian Empire in 1904-05." These victories demonstrated Japan's growing military might and gave the nation a needed confidence boost. Victory over Russia, a "Western nation," proved Japan had become global power. The world took notice.

Class mobility and economic freedoms ushered in by ending the samurai led feudal system spurred Japan's furious growth. The Meiji government's plans had begun to bear fruit.

NITOBE'S ULTERIOR MOTIVES

While the Meiji government plotted to strengthen Japan's presence on the world stage, Nitobe sought to change Westerners' perceptions of Japan from within.

At the time, Westerners knew little about the formerly isolated nation. Rumors about Japan – a feudalistic society whose armies relied on swords and bows and arrows – painted the picture of an unsophisticated, archaic island nation. In From Chivalry to Terrorism Leo Braudy writes, "Before World War I, many in Europe viewed Japan as a warrior society unadulterated by either commerce or the control of civilian politicians, with it's aristocratic military class still intact" (467).

Nitobe put faith in the power of his pen and began to write. By simplifying the most eloquent, ideal aspects of Japanese culture into terms the West could relate to, he hoped to paint a new, noble image of Japan. Writing in English only served to make Nitobe's contrivance more deliberate. Maria Navarro and Alison Beeby explain,

The original text (of Nitobe's book) was written in English, which was not Nitobe's mother tongue… Writing in a foreign language obliges one to "filter" one's own emotions and modes of expression… It allows the writer to express more empathy for the 'other culture' (in Nitobe's case Western culture). Furthermore, one is much more conscious of what one wants to say, or what one wishes to avoid saying, in order to make the work more acceptable for intended readers.

In 1899 Nitobe, "the self-described bridge between Japan and the West" published what would later become his most famous work, a romanticized, Westernized summation of the ideals of Japan's governing class, Bushido: The Soul of Japan (Braudy 467).

CHRISTIANITY AND THE TAMING OF THE SAMURAI

Bushido: The Soul of Japan represents a synthesis of Japanese culture with Western ideology. Nitobe tames Japan's samurai class by fusing it with European chivalry and Christian morality. "I wanted to show…" Nitobe admitted, "that the Japanese are not really so different (from people of the West)" (Benesch 165). Although it saw release years after the extinction of the samurai, Bushido: The Soul of Japan presents an original idealization and idolization of the samurai class.

Yet Nitobe shapes the concept of bushido around principles of Western culture, not the other way around as might be expected. Bushido: The Soul of Japan offers a suspicious lack of references to Japanese source material and historical fact. Instead, the student of English literature relies on Western works and personalities to explain the bushido's principals. Nitobe quotes the likes of Mencius, Frederick the Great, Burke, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, Shakespeare, James Hamilton and Bismarck – sources that that have no connection to Japan's history or culture.

In his self-proclaimed formulation of The Soul of Japan, the devout Christian references the Western Bible more than any other sources. Somehow Nitobe sees Bible quotes as appropriate and satisfactory support for bushido. "The seeds of the Kingdom (of God) as vouched for and apprehended by the Japanese mind," Nitobe declares, "blossomed in Bushido."

Nitobe spends much of the book ascribing bushido to the tenets of Christianity. Politeness, he quotes Corinthians 313, "suffereth long, and is kind; envieth not, vaunteth not itself" (50). Bushido's benevolence, Nitobe explains, is "embodied by the Christian Red Cross movement, the medical treatment of a fallen foe (46)."

Even a quote by Saigo Takamori, the legendary samurai, takes on a Biblical aura. "Heaven loves me and others with equal love; therefore with the love wherewith though lovest thyself, love others" (78). Nitobe himself admits, "Some of those sayings reminds us of Christian expostulations, and show us how far in practical morality natural religion can approach the revealed" (78).

Nitobe even goes as far as to paint the samurai as Japan's heavenly sent forefathers, holy mechanisms that shaped Japan. "What Japan was she owed to the samurai. They were not only the flower of the nation, but its root as well. All the gracious gifts of Heaven flowed through them" (Nitobe 92).

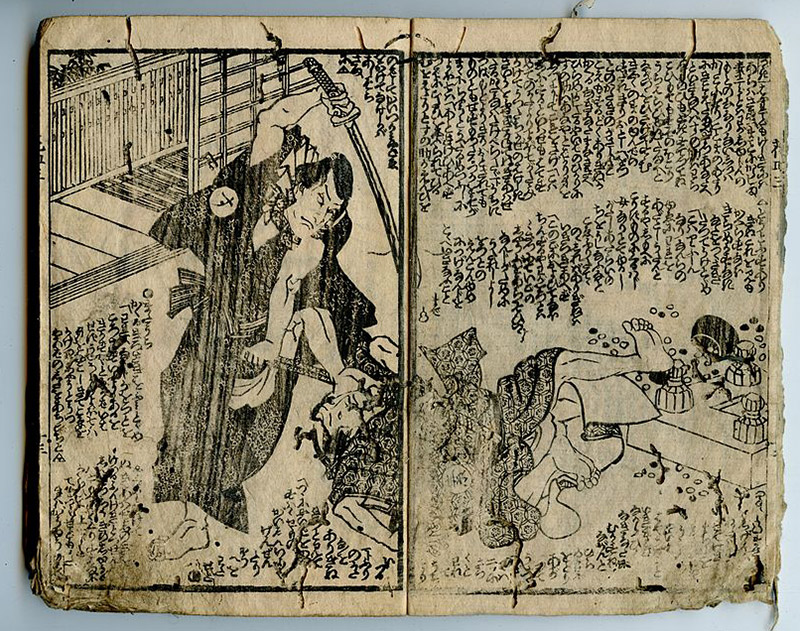

GIVING SOUL TO SUICIDE AND THE SWORD

In his taming of the samurai, Nitobe even justifies their most savage attributes – seppuku (also known as harakiri or ritual suicide) and the sword – under the guise of Christian mores. And it all starts with the soul.

Nitobe declares that in both Western and Japanese custom, the soul is housed in the stomach. "They (The Bible's Joseph, David, Isaiah and Jeremiah) all and each endorsed the belief prevalent among the Japanese that in the abdomen was enshrined the soul" (113).

This assertion allows Nitobe to exalt suicide to a holy act, "The highest estimate placed upon honor was ample excuse with many for taking one's own life," before challenging Western readers to resist his interpretation, "I dare say that many good Christians, if only they are honest enough, will confess the fascination of, if not positive admiration for, the sublime composure with which Cato, Brutus, Petronius, and a host of other ancient worthies terminated their own earthly existence." (113-114).

The sword receives similar treatment and Nitobe declares swordsmiths to be artists, not artisans; swords not weapons, but representations of their owners' souls. He explains:

The very possession of the dangerous instrument imparts to him (the samurai) a feeling and air of self-respect and responsibility. 'He beareth not the sword in vain' (Romans 13:4). What he carries in his belt is a symbol of what he carries in his mind and heart – loyalty and honor… In times of peace .. it is worn with no more use than a crosier by a bishop or a sceptre by a king (132-133).

Nitobe's skilled manipulation dignifies and venerates even Japan's most "savage" customs. The author's dedication to and knowledge of Christianity and Western culture allowed him to forge a propaganda tool under the guise of historic fact. Nitobe hoped Bushido: The Soul of Japan would change Western opinions of Japan, raising the country's status in the world's eyes.

THE SOUL OF JAPAN'S RECEPTION IN THE WEST

Bushido: The Soul of Japan became a hit with Western readers. "The slim volume," Tim Clark writes in The Bushido Code: The Eight Virtues of the Samurai, "went on to become an international bestseller," influencing some of the era's most influential men. Nitobe's treatise so impressed Teddy Roosevelt that he "bought sixty copies to share with friends" (Perez 280).

Although almost exclusively read by scholars, Nitobe's influence seeped into the Western conscious. Braudy writes, "This view of Bushido was an attractive image for Westerners… Balden-Powell has included bushido as an ideal code of honor in his exhortation to the Boy Scouts. Parliamentary groups… invoked the samurai as kindred spirit and writers on war preparedness haled up the samurai ethos of the Japanese army as a model to follow" (467).

Nitobe's account shocked readers by providing a glimpse into an unfamiliar, misunderstood world. With nothing to offer a counter point, Western readers accepted Bushido: The Soul of Japan as a factual representation of Japanese culture, and it remained the West's quintessential work on the topic for decades.

THE SOUL OF JAPAN'S RECEPTION IN JAPAN

Bushido: The Soul of Japan received a different reaction in Japan. Although bushido had yet to enter Japan's mainstream consciousness, scholars' interpretations of the concept varied and few agreed with Nitobe's representation. In fact,"Nitobe stated that he resisted the Japanese translation of his book for years out of fear of what readers might think" (Benesch 157). Many of those readers attacked Nitobe's work for its agenda and inaccuracies.

Oleg Benesch explains that most Japanese scholars did not take Nitobe's work seriously:

At the time of its initial publication, Nitobe's Bushido: The Soul Of Japan received a lukewarm reception from those Japanese who read the English edition. Tsuda Sokichi wrote a scathing critique in 1901, rejecting Nitobe's central arguments. According to Tsuda… the author knew very little about his subject. Nitobe's equation of the term bushido with the soul of Japan was flawed, as bushido could only be applied to a single class… Tsuda further chastised Nitobe for not distinguishing between historical periods. (155)

Many of Nitobe's contemporaries subscribed to an orthodox bushido based 0n Japan's ancient history. This purely Japanese form of bushido was seen as unique and superior to any foreign ideology. Orthodox writer Tetsujiro Inoue went as far as declaring European chivalry as "nothing but woman-worship" and even derided Confucianism as an inferior Chinese import (Benesch 179). The orthodox school of thought dismissed Nitobe's"corrupted," Christianized version of bushido.

To complicate matters, at the time of Bushido: The Soul of Japan's release, few Japanese even recognized the term bushido. In Musashi: The Dream of the Last Samurai Mamoru Oshii explains, "Bushido was not known among Japanese people… It appeared in literature, but was not a commonly used word."

Benesch supports Oshii's argument:

Indeed, (Bushido: The Soul of Japan) was only the second book-length specific treatment of the subject in modern Japan… Only four works in the database mention the term before 1895. The number of publications increases from a total of three in 1899 and 1900 to seven in 1901, six in 1902 and dozens per year from 1903 onward. (153)

Nitobe's treatise predated bushido as an understandable term and therefore appeared alien to its potential Japanese audience.

To make matters worse, Nitobe's book romanticized an old fashioned and exploitative class system everyone but the samurai hoped to leave behind. Accounts of samurai abusing the lower classes run rampant. Although rare, samurai could lawfully kill members of the lower class (kirisutegomen) for "surliness, discourtesy, and inappropriate conduct" (Cunnigham).

With such inequities, it's no surprise the lower classes felt no love for Japan's elite. Benesch writes, "The disdain most commoners had for the samurai has been described as legendary" (27). Not far removed from the inequities and immobility of the former class structure, the common people had no interest in idolizing or celebrating their former ruling class.

However, Nitobe wrote for Western audiences and therefore never intended for Bushido: The Soul of Japan to be read by Japanese readers. Nitobe wrote in English, referenced English sources and romanticized facts to satisfy his agenda and influence Western minds. He did not expect people with critical knowledge on the subject to read his work. "I did not intend [Bushido: The Soul of Japan] for a Japanese audience," Nitobe admitted (Benesch 165).

CRITIQUE OF INAZO NITOBE

Nitobe's "fear of what (Japanese) readers might think" proved sound when Bushido: The Soul of Japan received heavy criticism in Japan. However, Nitobe soon found himself under attack as well. Many Japanese scholars accused the author of being unqualified to write on bushido, questioning his expertise on Japanese history and culture.

Unlike the era's other bushido theorists, Nitobe inhabited the outskirts of his own country and culture. He grew up studying English, sheltered from Japanese culture in Hokkaido. Nitobe would go on to live abroad, marrying an American woman and dedicating himself to Christianity. Although he eventually returned to Japan and took work as a professor, it was long after Bushido: The Soul of Japan had been written and published. Critics claimed that Nitobe's alienation from Japanese culture meant he lacked the necessary historical and cultural knowledge to write on an inherently Japanese topic like bushido.

Nitobe's astounding lack of references to Japanese history and literature add weight to this argument. Bushido: The Soul of Japan remains curiously void of factual backing, becoming a vehicle for Nitobe's equivocal ramble and yearning for an imaginary past.

The few Japanese references Nitobe made call his integrity into question. For example, although Saigo Takamori did in fact lead the Satsuma Rebellion, the heroic motivations and suicide Nitobe references were embellished to lionize Saigo as the ideal samurai.

To be fair, many of Nitobe's critics also ignored factual history and cherry picked data for their own interpretations of bushido.

Many writers on bushido, even in the 20th century, tended to propose their own theories without references to, or regard for, the ideas of other commentators on the subject. Instead, they gradually relied on carefully selected historical sources and narratives to support their theories. (Benesch 116)

However, Nitobe's contemporaries' actions don't excuse his own. At its core, Bushido: The Soul of Japan presents baseless conjecture while exposing its author's detachment from Japanese history and culture. Nitobe forgoes fact while presenting a wonky rambling on a history he does not and can not support. While proselytizing a universal morality to gain Japan favor in the West, Nitobe fails to prove bushido's actual existence.

GIVE ME THAT NEW OLD-TIME BUSHIDO?

Popular culture presents bushido as a concrete moral code so intertwined with Japan's hallowed samurai class that the two appear inseparable. But in reality the term bushido did not exist until the twentieth century. In fact, Nitobe, one of the first scholars to embrace bushido, thought he created the term in 1900.

"Terms like budo (the martial way), bushi no michi (the way of the warrior), and yumiya no michi (the way of the bow and arrow) are far more common," Benesch writes (7). Although these terms prove that warrior ideals had a place in the Japanese consciousness, equating them to bushido would be inaccurate.

The concept bushido came into use during the Meiji era but wouldn't gain widespread acknowledgment until Meiji's end. Despite popular imagery, ancient samurai did not write about or discuss bushido. Dishonorable acts didn't end careers and lives as romanticized histories lead us to believe.

That isn't to say that ancient Japan lacked laws or moral codes – claiming such would be ridiculous. Rosalind Wiseman puts it best in her book Queen Bees and Wannabes, "We all know what an honor code is. It's a set of behavioral standards including discipline, character, fairness, and loyalty for people to uphold and live up to"(Wiseman 191). From small communities like workplaces and clubs to large institutions like religions and nations, every culture has honor codes and concepts of morality.

But popular representations of bushido, samurai, and ancient Japan depict a clear and strictly enforced code of honor. To dishonor oneself was to commit spiritual and physical suicide. Popularized after the samurai class's demise, books like Bushido: The Soul of Japan and Yamamoto Tsunetomo's Hagakure help facilitate this myth, making it seem as if samurai lived and acted according to a literal, clearly defined set of rules that never existed.

Some researchers cite kakun 家訓, or family house rules, as the origin of bushido. "In many cases the kakun were meant to serve as ethical and behavioral guidelines for the sons or heirs of the writers and often reflect concerns regarding the prosperity and the continuity of the clan" (Henry Smith).

Attributing family kakun to an overarching moral code is a leap most researchers don't take. Benesch comments, "Bushido receives little or no mention in postwar scholarship on medieval house codes… Evidence indicates that the association of bushido with (kakun) is a product of late Meiji-era interpretations" (8). Passed down from generation to generation kakun varied greatly by family. The scrolls became family heirlooms, not a set of rules to live by.

Early discourse on the subject exposes how vague warrior class values had been. "An examination of source materials and later scholarship relating to samurai morality does not reveal the existence of a single, broadly-accepted, bushi specific ethical system at any point in pre-modern Japanese history" (Benesch 14). Besides, warriors focused on victory and survival – battle didn't lend itself to counterproductive codes of honor.

Any laws or moral codes put into place during the Edo era actually served to tame Japan's wild, unprincipled warrior class as they moved from the battlefield to desk jobs. "The samurai were too busy fighting in earlier centuries, and only began to concern themselves with ethics in the relatively peaceful Edo period" (15).

With no battles to wage, the Tokugawa government relegated swords to ornaments of class, the ultimate status symbols. Samurai became upper-class bureaucrats with leisure time to spend on philosophical pursuits. Ideas of honor and etiquette frowned upon disloyalty and senseless violence, playing into the Tokugawa government's strategy to maintain control over a united Japan.

THE HONORABLE SAMURAI: FACT OR FICTION?

Bushido had never existed as an honor code or term in ancient Japan as Bushido: The Soul of Japanimplied. Nitobe's representation of the samurai class proves itself just as contrived. Like all human beings, samurai morals varied by individual.

HONORABLE WARRIORS?

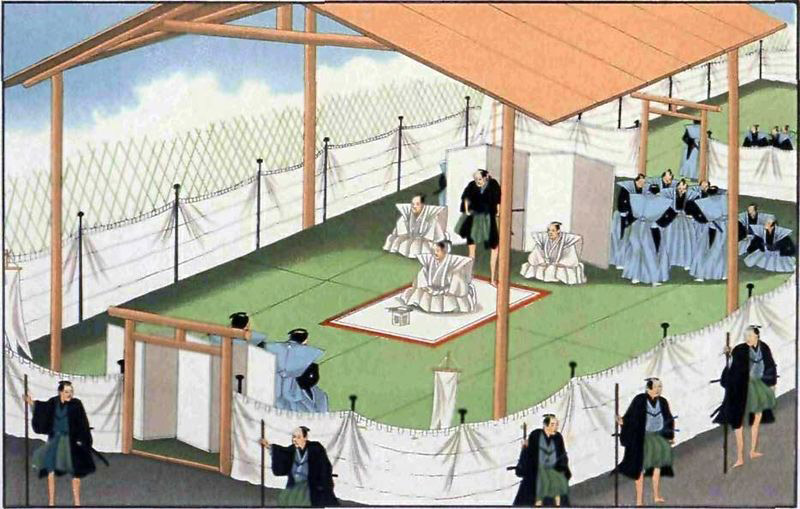

Historical accounts show that samurai did not follow an honor code, which would have been an impractical obstacle to survival, victory, and comfortable living. Timon Screech writes "We are talking mythologies. The belief that samurai ever fought to the death does not survive investigation, nor the claim that they made the sacrifice of disembowelment when atonement was required. The motto the way of the samurai is death was invented long after death had ceased to be on most samurai's minds or a reality in their lives… they were bureaucrats."

Although depicted as common practice, seppuku was not the mainstay of the samurai as Nitobe depicted. "It hurt too much," Screech explains. "Suicide actually took the form of a pretended stab carried out with a wooden sword, or even a paper fan, at which a signaled assistant would sever the head from behind, cleanly and painlessly."

Benesch writes that seppuku was "limited to hopeless situations in which a defeated warrior was certain to be subjected to torture, a common practice at the time" (16). Ignoring seppuku's factual history, writers romanticized the practice and exalted it to the ultimate form of honor.

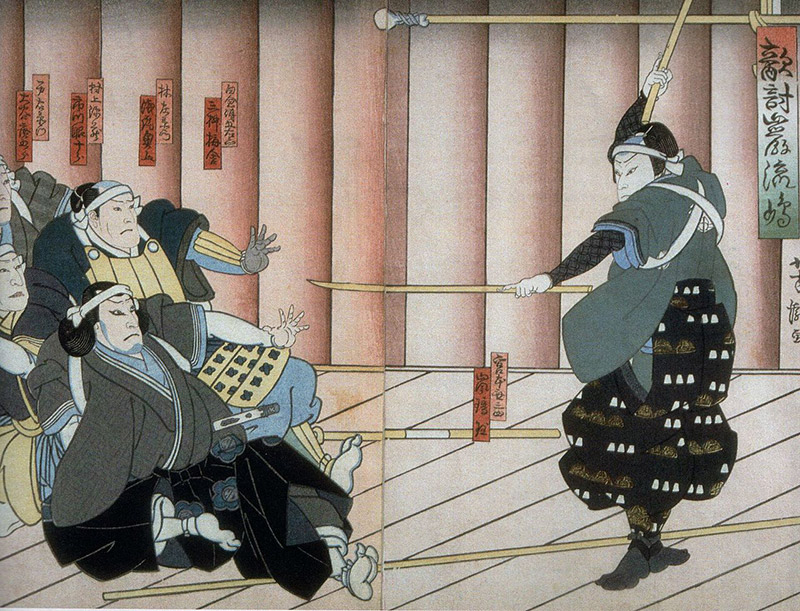

And what of the sword, the so-called soul of the samurai? Charles Sharam explains, "Prior to [the Tokugawa era], the samurai were in fact mounted archers who were highly skilled with the bow and arrow, occasionally using other weapons if necessary. For the greater part of their history, the sword was not an important weapon to the samurai."

Depicted as the antithesis of the sword in modern media, firearms came to represent the abandonment of "samurai values." The loud foreign weapons embodied a loud, dirty (literally due to the gunpowder and smoke), dishonorable way of killing from afar. But what about archery, the samurai's original weapon of choice? Though elegant, bows fired projectiles and killed from afar – just like firearms. Shouldn't archery be viewed as just as dishonorable as guns?

Furthermore, samurai had the privilege and advantage of mounted combat. In fact, Oshii theorizes that Miyamoto Mushashi created his legendary niten-ichi 二天一, or two sworded technique for better balance and more efficient killing from the saddle. Both the shooting and cutting down of foot-soldiers from a favorable mounted position clashes with the honorable image of the grounded sword fighter popularized by modern depictions of the samurai.

In Bushido: The Soul of Japan Nitobe describes loyalty as the shining attribute of the samurai class. However, samurai sullied Japanese history with rampant examples of disloyalty. G. Cameron Hurst III writes:

In fact, one of the most troubling problems of the premodern era is the apparent discrepancy between… codes exhorting the samurai to practice loyalty and the all-too-common incidents of disloyalty which racked medieval Japanese warrior life. It would not be an exaggeration to say that most crucial battles in medieval Japan were decided by the defection – that is, the disloyalty – of one or more of the major vassals of the losing general. (517)

And although bushido denounces materialism as a corruptive force, samurai weren't the epitome of anti-materialism that bushido writers like Nitobe described. Benesch explains:

Loyalty required payment. Reciprocity was expected at every stage of the process… and most samurai would have considered their own lives to be considerably more important than the lives of their superiors… (Furthermore) repeated looting of Kyoto evidenced of a lack of ethics, and the great importance warriors placed on appearance (represented) the antithesis of the popular image of the austere and frugal samurai. (19-21)

HONORABLE LIFESTYLES?

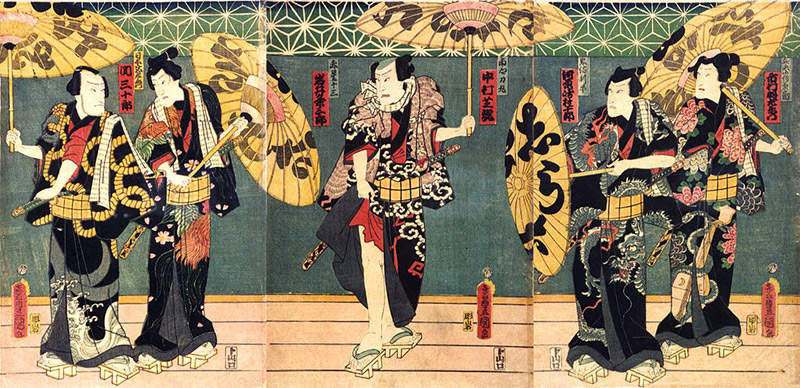

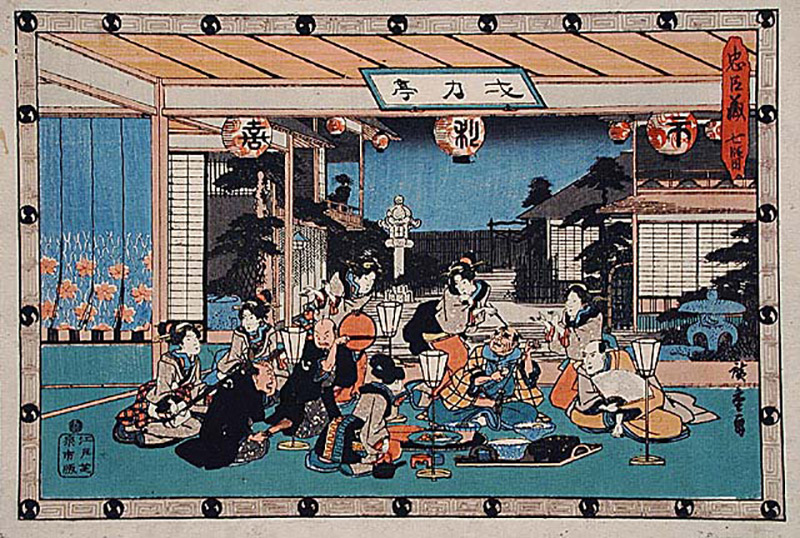

Tokugawa ushered in an unprecedented era of peace that forever altered the live's of Japan's warrior class. Many samurai moved from the battlefield to civil service positions. As society's upper class, these samurai held cushy positions in the new era's bureaucracy. Swords became symbols of status, not battle. With ample leisure time, these samurai enjoyed hobbies such as tea ceremony and calligraphy. Others spent time in the pleasure quarters.

While peasants toiled in the fields to feed the nation and pay taxes and merchants struggled to maintain a respectable position in society, the samurai worked desk jobs for rice stipends. Disposable income afforded samurai the luxuries of materialism and the former warriors became Japan's most fashionable class. In other words, samurai represented "the one percent" (actually six to eight percent according to Don Cunningham) of the Tokugawa era.

But not all samurai enjoyed life in the upper class. Low status samurai made small stipends that barely afforded daily living. Bound by the Tokugawa era's strict laws that forbade outside unemployment, some of these samurai renounced their status to become artisans or farmers (Cunningham).

Still other Tokugawa era samurai could not find employment. These vagrants often turned to dishonorable acts. As Don Cunningham explains in Taiho-jutsu: Law and Order in the Age of the Samurai, "Facing unemployment and an ill-defined role within their new society, many samurai resorted to criminal activities, disobedience, and defiance" (Cunningham). With few prospects and mounting frustrations, these samurai dressed and spoke flamboyantly, harassed lower classes, joined gangs, and brawled in the streets.

Whether elite civil servants or unemployed ruffians, Tokugawa era samurai did little to reinforce Nitobe's depictions of an honor-bound class that set a high moral standard for other classes to aspire to.

HONORABLE INTERPRETATIONS?

The loss of status ushered in by the Meiji government did not please those samurai accustomed to the Tokugawa system. Benesch states, "The samurai found their social status increasingly challenged by economically powerful commoners, some of whom were also purchasing or receiving samurai privileges such as the right to wear swords" (24). Rendered useless in an age of peace even the sword, "the soul" and symbol of the samurai had lost meaning. New class mobility allowed the uppity lower classes to challenge the samurai in both wealth and status.

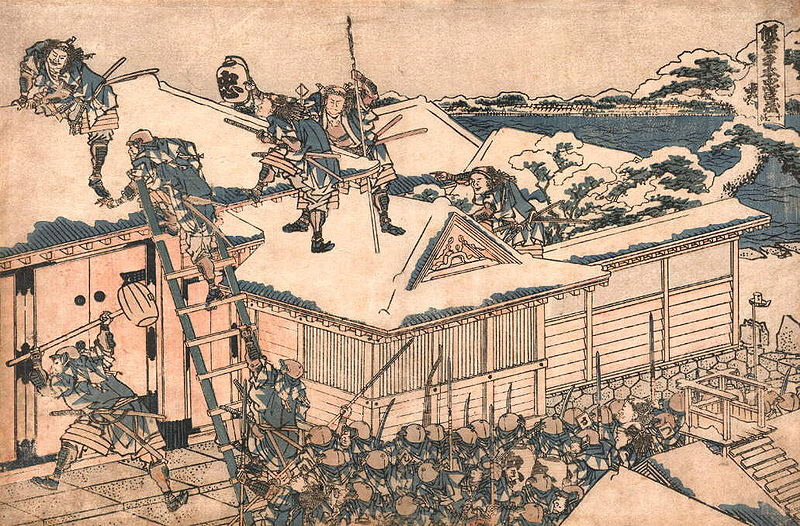

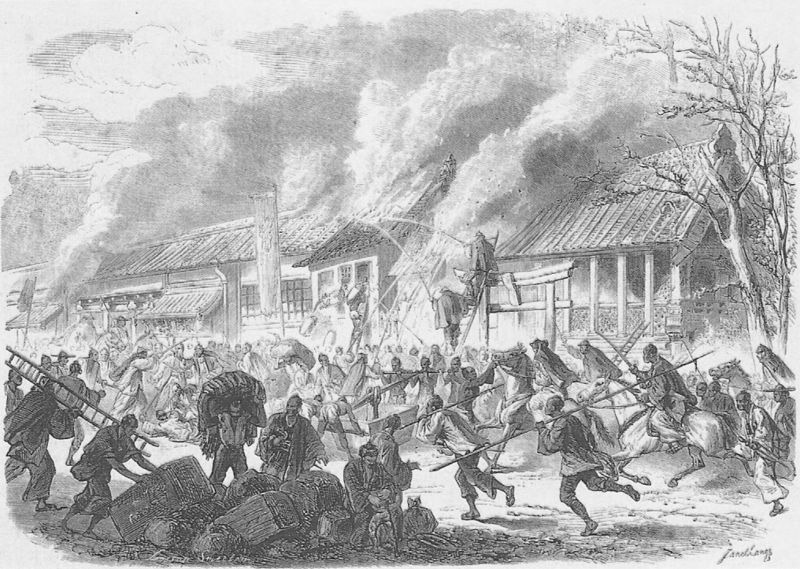

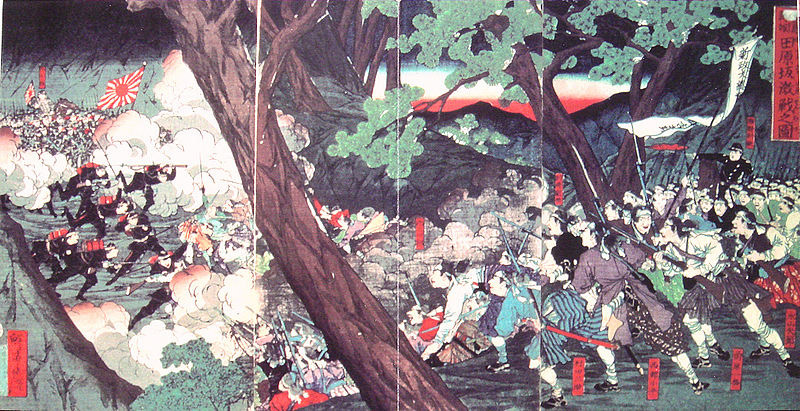

As the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 proves, the changes pushed some samurai to take action. "Gradually eliminating their stipends and special status… created a large group of disgruntled shizoku (samurai), a number of whom gathered around Saigo Takamori and instigated rebellion."

Romanticized histories like Bushido: The Soul of Japan and The Last Samurai, depict Saigo as a defender of truth, honor, and the purity of the warrior's code. In truth, holdouts from a bygone era rebelled, attempting to preserve their status and cushy way of life that included rice stipends, property, and nepotism. Professor Ohno points out:

The previous samurai class, now deprived of their rice salary… were particularly unhappy with the new government which was established, ironically by young samurai… Silk and tea found huge markets, soaring prices enriched farmers. Enriched farmers bought Western clothes. The merchant class grew, particularly in Yokohama… Inflation soared (and) samurai and urban populations suffered. (41-43)

Low ranking and unemployed samurai, many of whom pushed for changes, saw the Meiji era as a change for the better. A weakened class structure meant poor or unemployed samurai could seek fortune elsewhere. The abolition of the heredity system allowed for mobility. Suddenly those in high positions found incentive to work hard. Although a minority, Saigo and other top ranking samurai had the most to lose and rebelled as a result.

Lucky for Nitobe, honor is in the eye of the beholder, a concept open to interpretation. For example Nitobe cites The 47 Ronin Story as the ultimate example of loyalty, but others interpret it as a cowardly sneak attack. Japan celebrates Miyamoto Musashi as its most skilled sword-fighter, yet he arrived late to duels and "dishonorably" sneak-attacked opponents. Nitobe describes the Satsuma Rebellion as a battle of honor, not a rebellion driven by the preservation of class status.

Although Nitobe and his fellow writers lament the corruption and destruction of bushido by modernity, the concept never existed as they describe. Samurai were not the loyal, honorable, bastions of bushido that they have come to represent. Charles Sharam writes in The Samurai: Myth Versus Reality, "Samurai were a superfluous burden on Japanese civilization… that contributed little to society but drained a considerable amount of wealth. That said, their elimination in the years of the Meiji Restoration was most definitely warranted for the betterment of the nation."

FASCISM – NITOBE'S UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCE

Just decades after ousting the samurai, the Japanese government would find a new use for its former ruling class. Despite military victories abroad, Japanese officials felt troops lacked confidence and fighting spirit. Bushido's image of honorable samurai fighting to the death provided the solution (Oshii). The ideology that changed the West's perception of Japan would now serve to fuel fascism and the Japanese war machine.

According to Nitobe, Japan came from a long line of honorable, brave, and capable warriors that could be extended to all classes. He wrote, "In manifold ways has bushido filtered down from the social class where it originated, and acted as leaven among the masses, furnishing a moral standard for the whole people" (Nitobe).

Trickle down bushido meant even the lowliest citizen could aspire to and attain the glory and honor of a samurai. The warrior spirit was ingrained in the Japanese soul. By taking bushido mainstream, the Japanese government looked to boost its soldiers' and citizens' confidence by applying the ideology among its military and citizenry.

Furthermore, bushido justified Japan's imperialistic cause by demonstrating Japan's moral and cultural superiority to other nations. Bushido writer Suzuki Chikara "felt that both Western and Chinese thought were alien to Japan, and that the nation would have to focus on its own 'true spirit' and promote 'national spirit-ism'" (Benesch 101). Like America's Manifest Destiny and the religious zealotry that fueled the crusades, romanticized bushido served to motivate and rationalize Japan's imperialist agenda.

Now that it had found an ideology, the Japanese government had to make bushido "leaven among the masses" or moving propaganda. "Civilization and Enlightenment" and "Rich Nation, Strong Army" became wartime slogans. The nationalized education system streamlined curriculums to spread government rhetoric and foster an enlightened, battle-ready citizenry.

The national curriculum changed history to fit government agendas. "The Edo-period texts that showed the greatest nostalgia for pre-Tokugawa conditions were carefully selected, condensed, and edited to purge them of those elements which ran counter to the national project in the early twentieth century" (Benesch 21).

Mandatory texts romanticized past events and personalities. According to Oshii, "False images were created out of government necessity." Thanks to the government's agenda, unfamiliar entities like bushido, Hagakure and Miyamoto Musashi entered the mainstream conscious.

Nitobe's Bushido: The Soul of Japan gained popularity in prewar Japan thanks to its ideology and romanticism of the past. Nitobe declares, "Yamato Damashii, the soul of Japan, ultimately came to express the Volksgeist of the Island Realm" (27). Defined as the spirit of the people, Hitler embraced Volksgeist for his own fascist agenda (Griffen 255). Like bushido, Volksgeist celebrated its country's folk history, cultural heritage and race. These unrealistic nostalgias for the past sowed the seeds of fascism that would lead to the unspeakable violence and tragedies surrounding World War II.

Bushido would find its ultimate embodiment in kamikaze pilots and foot-soldiers who "honorably" sacrificed themselves for their country. "Although some Japanese were taken prisoner," David Powers of BBC writes, "most fought until they were killed or committed suicide." As these soldiers' government issued volumes of Hagakure taught, "Only a samurai prepared and willing to die at any moment can devote himself fully to his lord."

NITOBE'S LEGACY

Although he had never intended it, Nitobe's fanciful idealization of Japan's past had obvious fascist implications. In an eerie prediction of what was to come, Bushido: The Soul of Japan states,

Discipline in self-control can easily go too far. It can well repress the genial current of the soul. It can force pliant natures into distortions and monstrosities. It can beget bigotry, breed hypocrisy, or habituate affections. (110)

Both Nitobe and the imperialist government subverted the truth and exploited Japan's past for their own ulterior motives. Thanks to Nitobe, Japan's ancient soldiers and bureaucrats became honorable, spiritual warriors. More concerned with loyalty, benevolence, etiquette, and self-control than victory, monetary gains or rank in society, the samurai became a paradigm for readers to aspire to.

But history is ever-changing. True events fade from memory and years of interpretation's tincture, both intended and unintended, shape modern understandings of the past. Blurred mixtures of fact, opinion and fantasy enter mainstream consciousness and gain acceptance as "true" history.

Did Saigo Takamori really commit seppuku at the Satsuma Rebellion's end? Did Davy Crockett really fight to his death at the Alamo, or was he executed upon surrender as some historians believe? Was the Satsuma Rebellion a battle for virtue or for status? Was the Boston Tea Party a rebellion against unfair taxation or wealthy American merchants fighting to maintain their monopoly over tea? And what about George Washington cutting down his father's cherry tree? And his wooden teeth?

While the truth may never be known or agreed upon, it's important to question the events and the motivations behind our so-called histories. In Japan's case, government manipulated histories, including a glorified samurai class and bushido code, became propaganda that helped inspire a fanatical war machine.

Society often looks for answers to our present problems in the past. Like the current Tea Party movement's misinformed exploitation of America's past, Nitobe's bushido created a yearning for the unsubstantiated simplicity and purity of a bygone era.

As The Last Samurai proves, Nitobe's legacy lives on. Accurate or not, his simplified idealization of bushido and the samurai still garners the world's admiration. And as long as it does, popular culture will follow in the footsteps of both Inazo Nitobe and the Japanese government, exploiting their mythical image for its own motives – consumer's hard earned cash.