You can deny environmental calamity – until you check the facts

Rosy worldviews that rely on avoiding inconvenient truths should always set alarm bells ringing

One of the curiosities of our age is the way in which celebrity culture comes to dominate every aspect of public life. Even the review pages of the newspapers sometimes look like a highfalutin version of gossip magazines. Were we to judge them by the maxim “Great minds discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; small minds discuss people”, they would not emerge well. Biography dominates. Ideas often seem to come last. Brilliant writers such as Sylvia Plath are better known for their lives than their work. Turning her into the Princess Diana of literature does neither her nor her readers any favours.

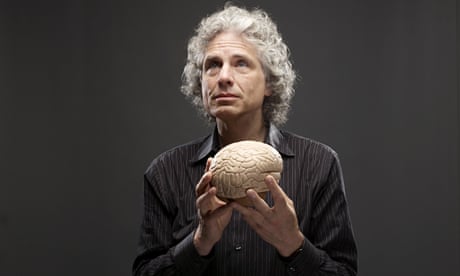

Even when ideas are given prominence, they no longer have standing in their own right. Their salience depends on their authorship. Take, for example, the psychology professor Steven Pinker, who attracts breathless adulation.

I am broadly sympathetic to his worldview. I agree with him that scientific knowledge is a moral imperative, and that we must use it to enhance human welfare. Like him, I’m enthusiastic about technologies that horrify other people, such as fourth-generation nuclear reactors and artificial meat. So I began reading his new book, Enlightenment Now, with excitement.

I expected something bracing, original, well sourced and well reasoned. Instead, in the area I know best – environmental issues – the alarm began to sound for me when he characterised “the mainstream environmental movement” as “laced with misanthropy, including an indifference to starvation, an indulgence in ghoulish fantasies of a depopulated planet, and Nazi-like comparisons of human beings to vermin, pathogens and cancer”.

Yes, I have come across such views, but they are few and far between. When they are expressed on social media, they are rapidly slapped down by other environmentalists. They are about as far from the environmental mainstream as they are from the humanitarian mainstream.

But this is just the beginning of the problem. Rather than using primary sources, Pinker draws on anecdote, cherry-picking and discredited talking points developed by anti-environmental thinktanks. Take, for example, Pinker’s claims about the landmark Limits to Growth report, published in 1972. It’s a favourite target of those who seek to dismiss environmental problems. He suggests it projected that aluminium, copper, chromium, gold, nickel, tin, tungsten and zinc would be exhausted by 1992. It is hard to see how anyone who had read the report could form this impression. The figures it uses for illustrative purposes have been transformed by some critics into projections.

Its actual prediction is that “the great majority of the currently important non-renewable resources will be extremely costly 100 years from now”. It would be perfectly reasonable to take issue with this claim. It is not reasonable to recycle, then attack, a widely circulated myth about the report. That’s called the straw man fallacy. It is contrary to the principles of reason that Pinker claims to champion.

Citing the famous ecologist Stuart Pimm, Pinker maintains that “the overall rate of extinctions has been reduced by 75%”. But Pimm has said no such thing. I checked with him. Pinker had latched on to a seven-word quote in the New Yorker, invested it with spurious precision, and misunderstood it as referring to all species rather than only birds. Pimm’s work has upgraded the overall extinction rate to 1,000 times the natural background rates, while “future rates are likely to be 10,000 times higher”.Like the straw man fallacy, cherrypicking offends the principles of reason.

He also claims that “we may have reached … Peak Car” (yet global car sales rose 11% between 2014 and 2017), and that as countries become richer “their thoughts turn to the environment”. In reality, the 2014 Greendex survey of 14 nations shows environmental concern has consistently been highest in India and China, and lowest in Britain, France, Japan, Canada and the US.

Pinker suggests that the environmental impact of nations follows the same trajectory, claiming that the “environmental Kuznets Curve” shows they become cleaner as they get richer. To support this point, he compares Nordic countries with Afghanistan and Bangladesh. It is true that they do better on indicators such as air and water quality, as long as you disregard their impacts overseas. But when you look at the whole picture, including carbon emissions, you discover the opposite. The ecological footprints of Afghanistan and Bangladesh (namely the area required to provide the resources they use) are, respectively, 0.9 and 0.7 hectares per person. Norway’s is 5.8, Sweden’s is 6.5 and Finland, that paragon of environmental virtue, comes in at 6.7.

Pinker seems unaware of the controversies surrounding the Kuznets Curve, and the large body of data that appears to undermine it. The same applies to the other grand claims with which he sweeps through this subject. He relies on highly tendentious interlocutors to interpret this alien field for him. If you are going to use people like US ecomodernist Stewart Brand and the former head of Northern Rock Matt Ridley as your sources, you need to doublecheck their assertions.Pinker insults the Enlightenment principles he claims to defend.

Could he have succumbed to the motivated reasoning these principles are supposed to suppress? If the environmental crisis cannot be so easily dismissed, it threatens his argument that life is steadily improving. What looks like a relentless enhancement in human welfare could emerge instead as an interlude between one form of deprivation and the next.

I doubt such poor scholarship will dim the adulation with which his claims are received. While Pinker is lauded, far more interesting and original books, such as Jeremy Lent’s The Patterning Instinct and Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, are scarcely reviewed. If there is one aspect of modernity that owes nothing to the Enlightenment, it is surely the worship of celebrities.

• George Monbiot is a Guardian columnist