Sky burial

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

This article is about the Tibetan funeral practice. For other uses, see Sky burial (disambiguation).

A sky burial site in Yerpa Valley, Tibet

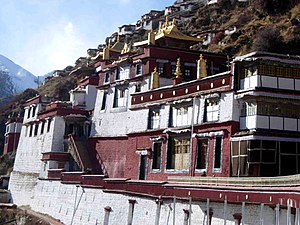

Drigung Monastery, Tibetan monastery famous for performing sky burials

Sky burial (Tibetan: བྱ་གཏོར་, Wylie: bya gtor, lit. "bird-scattered"[1]) is a funeral practice in which a human corpse is placed on a mountaintop to decompose while exposed to the elements or to be eaten by scavenging animals, especially carrion birds. It is a specific type of the general practice of excarnation. It is practiced in the Chinese provinces and autonomous regions of Tibet, Qinghai, Sichuan and Inner Mongolia, as well as in Mongolia, Bhutan and parts of India such as Sikkim and Zanskar.[2] The locations of preparation and sky burial are understood in the Vajrayana Buddhist traditions as charnel grounds. Comparable practices are part of Zoroastrian burial practices where deceased are exposed to the elements and birds of prey on stone structures called Dakhma.[3] Few such places remain operational today due to religious marginalisation, urbanisation and the decimation of vulture populations.[4][5]

The majority of Tibetan people and many Mongols adhere to Vajrayana Buddhism, which teaches the transmigration of spirits. There is no need to preserve the body, as it is now an empty vessel. Birds may eat it or nature may cause it to decompose. The function of the sky burial is simply to dispose of the remains in as generous a way as possible (the origin of the practice's Tibetan name). In much of Tibet and Qinghai, the ground is too hard and rocky to dig a grave, and due to the scarcity of fuel and timber, sky burials were typically more practical than the traditional Buddhist practice of cremation. In the past, cremation was limited to high lamas and some other dignitaries,[6] but modern technology and difficulties with sky burial have led to an increased use of cremation by commoners.[7]

Other nations which performed air burial were the Caucasus nations of Georgians, Abkhazians and Adyghe people, in which they put the corpse in a hollow tree trunk.[8][9]

Contents

1History and development

2Purpose and meaning

3Vajrayana iconography

4Setting

5Procedure

5.1Participants

5.2Disassembling the body

5.3Vultures

6Zoroastrianism

7In popular culture

8See also

9References

10Bibliography

11Further reading

12External links

History and development[edit source]

The Tibetan sky-burials appear to have evolved from ancient practices of defleshing corpses as discovered in archeological finds in the region.[10] These practices most likely came out of practical considerations,[11][12][13] but they could also be related to more ceremonial practices similar to the suspected sky burial evidence found at Göbekli Tepe (11,500 years before present) and Stonehenge (4,500 years BP).[citation needed] Most of Tibet is above the tree line, and the scarcity of timber makes cremation economically unfeasible. Additionally, subsurface interment is difficult since the active layer is not more than a few centimeters deep, with solid rock or permafrost beneath the surface.

The customs are first recorded in an indigenous 12th-century Buddhist treatise, which is colloquially known as the Book of the Dead (Bardo Thodol).[14] Tibetan tantricism appears to have influenced the procedure.[15][16] The body is cut up according to instructions given by a lama or adept.[17]

Vultures feeding on cut pieces of body at a 1985 sky burial in Lhasa, Tibet

Mongolians traditionally buried their dead (sometimes with human or animal sacrifice for the wealthier chieftains) but the Tümed adopted sky burial following their conversion to Tibetan Buddhism under Altan Khan during the Ming Dynasty and other banners subsequently converted under the Manchu Qing Dynasty.[18]

Sky burial was initially treated as a primitive superstition and sanitation concern by the Communist governments of both the PRC and Mongolia; both states closed many temples[18] and China banned the practice completely from the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s until the 1980s.[19] During this period, Sky burials were considered among the Four Olds, which was the umbrella term used by Communists to describe anti-proletarian customs, cultures and ideas. As a result of these policies, many corpses would simply be buried or thrown in rivers. Many families believed the souls of these people would never escape purgatory and became ghosts. Sky burial nonetheless continued to be practiced in rural areas and has even received official protection in recent years. However, the practice continues to diminish for a number of reasons, including restrictions on its practice near urban areas and diminishing numbers of vultures in rural districts. Finally, Tibetan practice holds that the yak carrying the body to the charnel grounds should be set free[citation needed], making the rite much more expensive than a service at a crematorium.[7][20]

Purpose and meaning[edit source]

Corpse being carried from Lhasa for sky burial about 1920

For Tibetan Buddhists, sky burial and cremation are templates of instructional teaching on the impermanence of life.[17] Jhator is considered an act of generosity on the part of the deceased, since the deceased and their surviving relatives are providing food to sustain living beings. Such generosity and compassion for all beings are important virtues in Buddhism.[21]

Although some observers have suggested that jhator is also meant to unite the deceased person with the sky or sacred realm, this does not seem consistent with most of the knowledgeable commentary and eyewitness reports, which indicate that Tibetans believe that at this point life has completely left the body and the body contains nothing more than simple flesh.

Only people who directly know the deceased usually observe it, when the excarnation happens at night.

Vajrayana iconography[edit source]

The tradition and custom of the jhator afforded Traditional Tibetan medicine and thangka iconography with a particular insight into the interior workings of the human body. Pieces of the human skeleton were employed in ritual tools such as the skullcup, thigh-bone trumpet.

The 'symbolic bone ornaments' (Skt: aṣṭhiamudrā; Tib: rus pa'i rgyanl phyag rgya) are also known as "mudra" or 'seals'. The Hevajra Tantra identifies the Symbolic Bone Ornaments with the Five Wisdoms and Jamgon Kongtrul in his commentary to the Hevajra Tantra explains this further.[22]

Setting[edit source]

1938 photo of Sky burial from the Bundesarchiv

A traditional jhator is performed in specified locations in Tibet (and surrounding areas traditionally occupied by Tibetans). Drigung Monastery is one of the three most important jhator sites.

The procedure takes place on a large flat rock long used for the purpose. The charnel ground (durtro) is always higher than its surroundings. It may be very simple, consisting only of the flat rock, or it may be more elaborate, incorporating temples and stupa (chorten in Tibetan).

Relatives may remain nearby[23] during the jhator, possibly in a place where they cannot see it directly. The jhator usually takes place at dawn.

The full jhator procedure (as described below) is elaborate and expensive. Those who cannot afford it simply place their deceased on a high rock where the body decomposes or is eaten by birds and animals.

In 2010, a prominent Tibetan incarnate lama, Metrul Tendzin Gyatso, visited the sky burial site near the Larung Gar Buddhist Institute in Sertar County, Sichuan, and was dismayed by its poor condition. With the stated goal of restoring dignity to the dead and creating a better environment for the vultures, the lama subsequently rebuilt and improved the platform where bodies are cut up, adding many statues and other carved features around it, and constructed a large parking lot for the convenience of visitors.[24]

Procedure[edit source]

Sky burial art at Litang monastery in Tibet

Accounts from observers vary. The following description is assembled from multiple accounts by observers from the U.S. and Europe. References appear at the end.

Participants[edit source]

Prior to the procedure, monks may chant mantra around the body and burn juniper incense – although ceremonial activities often take place on the preceding day.

The work of disassembling of the body may be done by a monk, or, more commonly, by rogyapas ("body-breakers").

All the eyewitness accounts remarked on the fact that the rogyapas did not perform their task with gravity or ceremony, but rather talked and laughed as during any other type of physical labor. According to Buddhist teaching, this makes it easier for the soul of the deceased to move on from the uncertain plane between life and death onto the next life.

Some accounts refer to individuals who carry out sky burial rituals as a ‘Tokden’ which is Tibetan for ‘Sky Burial Master’. While a Tokden has an important role in burial rites, they are often people of low social status and sometimes receive payment from the families of the deceased.

Disassembling the body[edit source]

A body being prepared for Sky burial in Sichuan

According to most accounts, vultures are given the whole body. Then, when only the bones remain, these are broken up with mallets, ground with tsampa (barley flour with tea and yak butter, or milk) and given to the crows and hawks that have waited for the vultures to depart.

In one account, the leading rogyapa cut off the limbs and hacked the body to pieces, handing each part to his assistants, who used rocks to pound the flesh and bones together to a pulp, which they mixed with tsampa before the vultures were summoned to eat. In some cases, a Todken will use butcher's tools to divide the body.

Sometimes the internal organs were removed and processed separately, but they too were consumed by birds. The hair is removed from the head and may be simply thrown away; at Drigung, it seems, at least some hair is kept in a room of the monastery.

None of the eyewitness accounts specify which kind of knife is used in the jhator. One source states that it is a "ritual flaying knife" or trigu (Sanskrit kartika), but another source expresses skepticism, noting that the trigu is considered a woman's tool (rogyapas seem to be exclusively male).

Vultures[edit source]

Skeletal remains as vultures feed

The species contributing to the ritual are typically the griffon and Himalayan vultures.

In places where there are several jhator offerings each day, the birds sometimes have to be coaxed to eat, which may be accomplished with a ritual dance. If a small number of vultures come down to eat, or if portions of the body are left over after the vultures fly away, or if the body is completely left untouched, it is considered to be a bad omen in Buddhist beliefs.[25] In these cases, according to Buddhist belief, there are negative implications for the individual and/or the individual's family, such as the individual being buried lived a bad life or accumulated bad karma throughout their lifetime and throughout their past lives, thus predetermining them to a bad rebirth.[26]

In places where fewer bodies are offered, the vultures are more eager, and sometimes have to be fended off with sticks during the initial preparations. Often there is a limit to how many corpses can be consumed at a certain burial site, prompting lamas to find different areas. It is believed that if too many corpses are disposed in a certain burial site, ghosts may appear.

Not only are vultures an important aspect to celestial burial but also to its habitat's ecology. They contribute to carcass removal and nutrient recycling, as they are scavengers of the land.[27] Due to an alarming drop in their population, in 1988, the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife added certain species of vultures into the "rare" or "threatened" categories of their national list of protected wild animals.[28] Local Chinese governments surrounding sky burial locations have established regulations to avoid disturbance of the vultures during these rituals, as well as to not allow individuals who have passed away due to infectious diseases or toxicosis from receiving a sky burial in order to prevent compromising the health of the vultures.[29]

Zoroastrianism[edit source]

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Sky burial" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Ancient Zoroastrians believed the dead body should be put in a structure called a Dakhma to be feasted upon by birds of prey, because the burial or burning of the corpses would cause water and soil to become dirty, which is forbidden in the ancient religion.

In popular culture[edit source]

This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. Please reorganize this content to explain the subject's impact on popular culture, providing citations to reliable, secondary sources, rather than simply listing appearances. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2021)

A jhator was filmed, with permission from the family, for Frederique Darragon's documentary Secret Towers of the Himalayas, which aired on the Science Channel in fall 2008. The camera work was deliberately careful to never show the body itself, while documenting the procedure, birds, and tools.

The ritual was featured in films such as The Horse Thief, Kundun, and Himalaya.

A sky burial was shown in BBC's Human Planet – Mountains.

The semi-autobiographical book Wolf Totem discusses sky burial.

Sky burials are among the methods of burial discussed in Neil Gaiman's The Sandman: Worlds' End.

In the 2015 video game Bloodborne, Eileen the Crow's bird-like attire is a reference to the practice of Sky Burial. This is told explicitly in her attire's item descriptions.

See also[edit source]

Disposal of human corpses

Burial tree

Tower of Silence or Dakhma, the Zoroastrian structure for exposure of the dead

References[edit source]

^ "How Sky Burial Works". 25 July 2011.

^ Sulkowsky, Zoltan (2008). Around the World on a Motorcycle. Whitehorse Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-884313-55-4.

^ BBC. "Zoroastrian funerals Towers of Silence". 02 Oct 2009. Accessed 08 Sep 2014.

^ New York Times. "Giving New Life to Vultures to Restore a Human Ritual of Death". 29 Nov 2012. Accessed 08 Sep 2014.

^ npr. "Vanishing Vultures A Grave Matter For India's Parsis". 05 Sep 2012. Accessed 08 Sep 2014.

^ "Sky Burial, Tibetan Religious Ritual, Funeral Party". www.travelchinaguide.com.

^ Jump up to:a b China Daily. "Funeral reforms in Tibetan areas". 13 Dec 2012. Accessed 18 Jul 2013.

^ "ИСТОРИЯ ГРУЗИИ" (in Russian).

^ "ОПИСАНИЕ КОЛХИДЫ ИЛИ МИНГРЕЛИИ" (in Russian).

^ PBS. "Cave People of the Himalaya".

^ Wylie 1965, p. 232.

^ Martin 1996, pp. 360–365.

^ Joyce & Williamson 2003, p. 815.

^ Martin 1991, p. 212.

^ Ramachandra Rao 1977, p. 5.

^ Wylie 1964.

^ Jump up to:a b Goss & Klass 1997, p. 385.

^ Jump up to:a b Heike, Michel. "The Open-Air Sacrificial Burial of the Mongols". Accessed 18 Jul 2013.

^ Faison 1999, para. 13.

^ "Funeral reforms edge along in Tibetan areas". Xinhua. 2012-12-13. Retrieved 2012-12-16.

^ Mihai, Andrei (November 9, 2009). "The Sky Burial". ZME Science. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

^ Kongtrul 2005, p. 493.

^ Ash 1992, p. 59.

^ "喇榮五明佛學院屍陀林:帶你走進生命輪迴的真相". 28 September 2016.

^ MaMing, Roller; Lee, Li; Yang, Xiaomin; Buzzard, Paul (2018-03-29). "Vultures and sky burials on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau". Vulture News. 71 (1): 22. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v71i1.2. ISSN 1606-7479.

^ Gouin, Margaret (2010). Tibetan Rituals of Death: Buddhist Funerary Practices. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 9780203849989.

^ MaMing, Roller; Xu, Guohua (2015-11-12). "Status and threats to vultures in China". Vulture News. 68 (1): 10. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v68i1.1. ISSN 1606-7479.

^ MaMing, Roller; Xu, Guohua (2015-11-12). "Status and threats to vultures in China". Vulture News. 68 (1): 5. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v68i1.1. ISSN 1606-7479.

^ MaMing, Roller; Lee, Li; Yang, Xiaomin; Buzzard, Paul (2018-03-29). "Vultures and sky burials on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau". Vulture News. 71 (1): 30. doi:10.4314/vulnew.v71i1.2. ISSN 1606-7479.

Bibliography[edit source]

Ash, Niema (1992), Flight of the Wind Horse: A Journal into Tibet, London: Rider, pp. 57–61, ISBN 0-7126-3599-8.

Bruno, Ellen (2000), Sky Burial|11 minute film, Bruno Films.

Dechen, Pemba (2012), "Rinchen, the Sky-Burial Master", Manoa, University of Hawai’i Press, 24 (1): 92–104, doi:10.1353/man.2012.0016, JSTOR 42004645, S2CID 143258606

Faison, Seth (July 3, 1999). "Lirong Journal; Tibetans, and Vultures, Keep Ancient Burial Rite". New York Times. nytimes.com..

Goss, Robert E.; Klass, Dennis (1997), "Tibetan Buddhism and the resolution of grief: The Bardo-Thodol for the dying and the grieving", Death Studies, 21 (4): 377–395, doi:10.1080/074811897201895, PMID 10170479.

Joyce, Kelly A.; Williamson, John B. (2003), "Body recycling", in Bryant, Clifton D. (ed.), Handbook of Death & Dying, 2, Thousand Oaks: Sage, ISBN 0-7619-2514-7.

Kongtrul Lodrö Tayé, Jamgön (2005), Systems of Buddhist Tantra, The Indestructible Way of Secret Mantra, The Treasury of Knowledge, book 6, part 4, Boulder: Snow Lion, ISBN 1-55939-210-X.

Martin, Daniel Preston (1991), The Emergence of Bon and the Tibetan Polemical Tradition, (Ph.D. thesis), Indiana University Press, OCLC 24266269.

Martin, Daniel Preston (1996), "On the Cultural Ecology of Sky Burial on the Himalayan Plateau", East and West, 46 (3–4): 353–370.

Mullin, Glenn H. (1998). Living in the Face of Death: The Tibetan Tradition. 2008 reprint: Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, New York. ISBN 978-1-55939-310-2.

Ramachandra Rao, Saligrama Krishna (1977), Tibetan Tantrik Tradition, New Delhi: Arnold Heinemann, OCLC 5942361.

Wylie, Turrell V. (1964), "Ro-langs: the Tibetan zombie", History of Religions, 4 (1): 69–80, doi:10.1086/462495, S2CID 162285111.

Wylie, Turrell V. (1965), "Mortuary Customs at Sa-Skya, Tibet", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 25, 25: 229–242, doi:10.2307/2718344, JSTOR 2718344.

Further reading[edit source]

Entry on jhator in Dakini Yogini Central

External links[edit source]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sky burial.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sky burial.Eyewitness account, Niema Ash, 1980s

Survival and Evolution of Sky Burial Practices in Tibetan Areas of China, Pamela Logan, 2019

Eyewitness account, Mondo Secter, 1999 - This page also includes references and links to other eyewitness accounts and to a 1986 documentary film that shows a jhator

Description of Drigung site, Keith Dowman, orig. pub. 1988

Photos in Tibet

Sky Burial video From TravelTheRoad.com

Sky Burial Footage available on YouTube

Laribee, Rachel (May 2005), "Tibetan Sky Burial: Student Witnesses Reincarnation" (PDF), River Gazette, p. 9, archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-08.

Categories:

Death customs

Tibetan culture

Tibetan Buddhist practic

鳥葬

概要[編集]

チベット仏教にて行われるのが有名である。またパールスィーと呼ばれるインドのゾロアスター教徒も鳥葬を行う。国や地域によっては、法律などにより違法行為となる。日本では、鳥葬の習慣はないが、もし行った場合刑法190条の死体損壊罪に抵触する恐れがある。

チベットの鳥葬はムスタンの数百年後に始まったと考えられ、現在も続いている。

ゾロアスターは古代ペルシア(現在のイラン)にルーツを持ち、死者の肉を削ぎ動物に与える風習があった[1]。

カリフォルニア大学マーセド校の考古学者マーク・アルデンダーファー(Mark Aldenderfer)は、「ゾロアスター教の葬儀をアッパームスタンの古代人が取り入れ、その後にチベットの鳥葬へと形を変えた可能性がある」という仮説を提示している[1]。

チベットの鳥葬[編集]

| 画像外部リンク | |

|---|---|

| 閲覧注意 | |

| 画像外部リンク | |

|---|---|

| 閲覧注意 | |

チベットの葬儀は5種類あるとされる。すなわち塔葬・火葬・鳥葬・水葬・土葬である。このうち塔葬はダライ・ラマやパンチェン・ラマなどの活仏に対して行われる方法であり、一般人は残りの4つの方法が採られる。チベット高地に住むチベット人にとって、最も一般的な方法が鳥葬である。葬儀に相当する儀式により、魂が解放された後の肉体はチベット人にとっては肉の抜け殻に過ぎない。その死体を郊外の荒地に設置された鳥葬台に運ぶ。それを裁断し断片化してハゲワシなどの鳥類に食べさせる。これは、死体を断片化する事で血の臭いを漂わせ、鳥類が食べやすいようにし、骨などの食べ残しがないようにするために行うものである。

宗教上は、魂の抜け出た遺体を「天へと送り届ける」ための方法として行われており、鳥に食べさせるのはその手段に過ぎない。日本では鳥葬という訳語が採用されているが、中国語では天葬などと呼ぶ。また、多くの生命を奪ってそれを食べることによって生きてきた人間が、せめて死後の魂が抜け出た肉体を、他の生命のために布施しようという思想もある。死体の処理は、鳥葬を執り行う専門の職人が行い、骨も石で細かく砕いて鳥に食べさせ、あとにはほとんど何も残らない。ただし、地域によっては解体・断片化をほとんど行わないため、骨が残される場合もある。その場合は骨は決まった場所に放置される。職人を充分雇えない貧しい人達で大きな川が近くにある場合は水葬を行う。水葬もそのまま死体を川に流すのではなく、体を切断したうえで実施される。

鳥葬はチベット仏教の伝播している地域で広く行われ、中国のチベット文化圏だけでなくブータン・ネパール北部・インドのチベット文化圏の一部・モンゴルのごく一部でも行われる。ただ、他の国のチベット人には別の葬儀方法が広まりつつある。

チベット高地で鳥葬が一般的になった理由のひとつに、火葬や土葬は環境に対する負荷が大きすぎることもある。大きな木がほとんど生えないチベット高地で火葬を行うためには、薪の確保が困難である。しかし、森林の豊富な四川省のチベット人は火葬が一般的である。土葬も、寒冷なチベットにおいては微生物による分解が完全に行われず、かつ土が固くて穴掘りが困難なこともあり、伝染病の死者に対し行われる方法である。伝染病患者を鳥葬・水葬にすると病原体の拡散が起こりうるからである。

中国の西蔵自治区当局は鳥葬は非衛生的だとして火葬を奨励していたが、2006年に鳥葬について撮影や報道を禁ずる条例を公布して、伝統文化を保護することになった。チベットには約1000箇所の鳥葬用石台があるが、関係者以外による撮影や見物、および鳥葬用石台近くの採石など開発行為も禁じた。

ゾロアスター教の鳥葬[編集]

ゾロアスター教では、死体は悪魔の住処とされ、葬式は悪魔による汚濁の源を浄化するための儀礼であった[2]。 善神の象徴として火を崇拝するゾロアスター教では、死体が火を穢すことになるため、火葬を行わず、同様の理由で土葬や水葬も行わない。 ササン朝ペルシア時代のゾロアスター教では、死体は路傍に放置されハゲワシに食われるか、直射日光で乾燥して骨だけになった後にダフマと呼ばれる磨崖穴に入れられる曝葬が行われていた[3]。

インドに流入したゾロアスター教の教徒(パールスィー)もその伝統を受け継いだが、イラン高原と異なり湿潤なインドでは死体が乾燥する前に腐乱してしまうため、磨崖穴にちなんでダフマと名付けられた鳥葬専用の施設を使用している[3]。 英語で沈黙の塔と呼ばれるタワー型のダフマは、古代ローマのコロッセウムにも似た開口部のある円筒状の塔であり、その上に置かれた死体は鳥がついばんで骨となり、骨は陽光によって漂白される。そして最終的には土に還るというわけである。その際、すみやかに骨のみになるとよいとされる。

葬儀は亡くなったその日に行われるのが良いとされるが、日没後には行われない。遺体は金属製の台に乗せられ、ダフマの近くまで葬列を組んで送られる。遺族はダフマの近くで最後の別れを行い、遺体運搬人によるダフマへの行進を見届けた後、身を清めて没後3日間死者のための儀式を行う[2]。

ダフマはインドのムンバイに2基、ナヴサーリーに2基あるほか、インド亜大陸のパールスィー居住区では数多く見ることが出来る[3]。

脚注[編集]

- ^ a b 肉を削ぐ未知の葬儀を発見、ヒマラヤ ナショナルジオグラフィック

- ^ a b ジョン・R・ヒネルズ『ペルシア神話』井本英一、奥西峻介訳 青土社 1993年 ISBN 4791752724 pp.272-278.

- ^ a b c 青木健『ゾロアスター教』 <講談社選書メチエ> 講談社 2008年 ISBN 9784062584081 pp.184-185.