Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings.

The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian Nestorius (d. c. 450 AD), who promoted specific doctrines in the fields of Christology and Mariology.

The second meaning of the term is much wider, and relates to a set of later theological teachings, that were traditionally labeled as Nestorian, but differ from the teachings of Nestorius in origin, scope and terminology.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines Nestorianism as "The doctrine of Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople (appointed in 428), by which Christ is asserted to have had distinct human and divine persons."[3]

Original Nestorianism is attested primarily by works of Nestorius, and also by other theological and historical sources that are related to his teachings in the fields of Mariology and Christology. His theology was influenced by teachings of Theodore of Mopsuestia (d. 428), the most prominent theologian of the Antiochian School. Nestorian Mariology rejects the title Theotokos ('God-bearer') for Mary, thus emphasizing distinction between divine and human aspects of the Incarnation. Nestorian Christology promotes the concept of a prosopic union of two natures (divine and human) in Jesus Christ, thus trying to avoid and replace the concept of a hypostatic union. This Christological position is defined as radical dyophysitism, and differs from orthodox dyophysitism, that was reaffirmed at the Council of Chalcedon (451). Such teachings brought Nestorius into conflict with other prominent church leaders, most notably Cyril of Alexandria, who issued 12 anathemas against him (430). Nestorius and his teachings were eventually condemned as heretical at the Council of Ephesus in 431, and again at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. His teachings were considered as heretical not only in Chalcedonian Christianity, but even more in Oriental Orthodoxy.

After the condemnation, some supporters of Nestorius, who were followers of the Antiochian School and the School of Edessa, relocated to the Sasanian Empire, where they were affiliated with the local Christian community, known as the Church of the East. During the period from 484 to 612, gradual development led to the creation of specific doctrinal views within the Church of the East. Evolution of those views was finalized by prominent East Syriac theologian Babai the Great (d. 628) who was using the specific Syriac term qnoma (ܩܢܘܡܐ) as a designation for dual (divine and human) substances within one prosopon (person or hypostasis) of Christ. Such views were officially adopted by the Church of the East at a council held in 612. Opponents of such views labeled them as "Nestorian" thus creating the practice of misnaming the Church of the East as Nestorian. For a long time, such labeling seemed appropriate, since Nestorius is officially venerated as a saint in the Church of the East. In modern religious studies, this label has been criticized as improper and misleading. As a consequence, the use of Nestorian label in scholarly literature, and also in the field of inter-denominational relations, is gradually being reduced to its primary meaning, focused on the original teachings of Nestorius.

History[edit]

Nestorianism was condemned as heresy at the Council of Ephesus (431). The Armenian Church rejected the Council of Chalcedon (451) because they believed Chalcedonian Definition was too similar to Nestorianism. The Persian Nestorian Church, on the other hand, supported the spread of Nestorianism in Persarmenia. The Armenian Church and other eastern churches saw the rise of Nestorianism as a threat to the independence of their Church. Peter the Iberian, a Georgian prince, also strongly opposed the Chalcedonian Creed.[13] Thus, in 491, Catholicos Babken I of Armenia, along with the Albanian and Iberian bishops met in Vagharshapat and issued a condemnation of the Chalcedonian Definition.[14]

Nestorians held that the Council of Chalcedon proved the orthodoxy of their faith and had started persecuting non-Chalcedonian or Miaphysite Syriac Christians during the reign of Peroz I. In response to pleas for assistance from the Syriac Church, Armenian prelates issued a letter addressed to Persian Christians reaffirming their condemnation of the Nestorianism as heresy.[13]

Following the exodus to Persia, scholars expanded on the teachings of Nestorius and his mentors, particularly after the relocation of the School of Edessa to the (then) Persian city of Nisibis (modern-day Nusaybin in Turkey) in 489, where it became known as the School of Nisibis.[citation needed] Nestorian monasteries propagating the teachings of the Nisibis school flourished in 6th century Persarmenia.[13]

Despite this initial Eastern expansion, the Nestorians' missionary success was eventually deterred. David J. Bosch observes, "By the end of the fourteenth century, however, the Nestorian and other churches—which at one time had dotted the landscape of all of Central and even parts of East Asia—were all but wiped out. Isolated pockets of Christianity survived only in India. The religious victors on the vast Central Asian mission field of the Nestorians were Islam and Buddhism".[15]

Doctrine[edit]

A historical misinterpretation of the Nestorian view was that it taught that the human and divine persons of Christ are separate.[16] Nestorianism is a radical form of dyophysitism, differing from orthodox dyophysitism on several points, mainly by opposition to the concept of hypostatic union. It can be seen as the antithesis to Eutychian Monophysitism, which emerged in reaction to Nestorianism. Where Nestorianism holds that Christ had two loosely united natures, divine and human, Monophysitism holds that he had but a single nature, his human nature being absorbed into his divinity. A brief definition of Nestorian Christology can be given as: "Jesus Christ, who is not identical with the Son but personally united with the Son, who lives in him, is one hypostasis and one nature: human."[17] This contrasts with Nestorius' own teaching that the Word, which is eternal, and the Flesh, which is not, came together in a hypostatic union, 'Jesus Christ', Jesus thus being both fully man and God, of two ousia (Ancient Greek: οὐσία) (essences) but of one prosopon (person). Both Nestorianism and Monophysitism were condemned as heretical at the Council of Chalcedon.

Nestorius developed his Christological views as an attempt to understand and explain rationally the incarnation of the divine Logos, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity as the man Jesus. He had studied at the School of Antioch where his mentor had been Theodore of Mopsuestia; Theodore and other Antioch theologians had long taught a literalist interpretation of the Bible and stressed the distinctiveness of the human and divine natures of Jesus. Nestorius took his Antiochene leanings with him when he was appointed Patriarch of Constantinople by Byzantine emperor Theodosius II in 428.

Nestorius's teachings became the root of controversy when he publicly challenged the long-used title Theotokos[19] ('God-Bearer') for Mary. He suggested that the title denied Christ's full humanity, arguing instead that Jesus had two persons (dyoprosopism),[20] the divine Logos and the human Jesus. As a result of this prosopic duality, he proposed Christotokos ('Christ-Bearer') as a more suitable title for Mary. He also advanced the image of Jesus as a warrior-king and rescuer of Israel over the traditional image of the Christus dolens.[21]

Nestorius' opponents found his teaching too close to the heresy of adoptionism – the idea that Christ had been born a man who had later been "adopted" as God's son. Nestorius was especially criticized by Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, who argued that Nestorius's teachings undermined the unity of Christ's divine and human natures at the Incarnation. Some of Nestorius's opponents argued that he put too much emphasis on the human nature of Christ, and others debated that the difference that Nestorius implied between the human nature and the divine nature created a fracture in the singularity of Christ, thus creating two Christ figures.[22] Nestorius himself always insisted that his views were orthodox, though they were deemed heretical at the Council of Ephesus in 431, leading to the Nestorian Schism, when churches supportive of Nestorius and the rest of the Christian Church separated. However, this formulation was never adopted by all churches termed 'Nestorian'. Indeed, the modern Assyrian Church of the East, which reveres Nestorius, does not fully subscribe to Nestorian doctrine, though it does not employ the title Theotokos.[23]

Nestorian Schism[edit]

Nestorianism became a distinct sect following the Nestorian Schism, beginning in the 430s. Nestorius had come under fire from Western theologians, most notably Cyril of Alexandria. Cyril had both theological and political reasons for attacking Nestorius; on top of feeling that Nestorianism was an error against true belief, he also wanted to denigrate the head of a competing patriarchate.[citation needed] Cyril and Nestorius asked Pope Celestine I to weigh in on the matter. Celestine found that the title Theotokos[19] was orthodox, and authorized Cyril to ask Nestorius to recant. Cyril, however, used the opportunity to further attack Nestorius, who pleaded with Emperor Theodosius II to call a council so that all grievances could be aired.[23]

In 431 Theodosius called the Council of Ephesus. However, the council ultimately sided with Cyril, who held that the Christ contained two natures in one divine person (hypostasis, unity of subsistence), and that the Virgin Mary, conceiving and bearing this divine person, is truly called the Mother of God (Theotokos). The council accused Nestorius of heresy, and deposed him as patriarch.[24] Upon returning to his monastery in 436, he was banished to Upper Egypt. Nestorianism was officially anathematized, a ruling reiterated at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. However, a number of churches, particularly those associated with the School of Edessa, supported Nestorius – though not necessarily his doctrine – and broke with the churches of the West. Many of Nestorius' supporters relocated to the Sasanian Empire of Iran, home to a vibrant but persecuted Christian minority.[25] In Upper Egypt, Nestorius wrote his Book of Heraclides, responding to the two councils at Ephesus (431, 449).

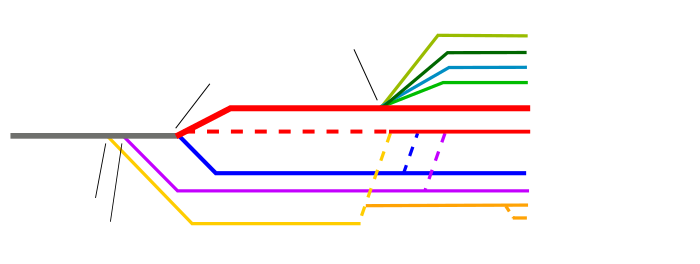

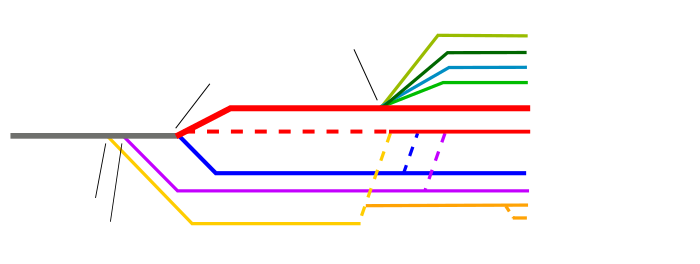

Christian denomination tree[edit]

(16th century)

(11th century)

- (Not shown are non-Nicene, nontrinitarian, and some restorationist denominations.)

Church of the East[edit]

The western provinces of the Persian Empire had been home to Christian communities, headed by metropolitans, and later patriarchs of Seleucia-Ctesiphon. The Christian minority in Persia was frequently persecuted by the Zoroastrian majority, which accused local Christians of political leanings towards the Roman Empire. In 424, the Church in Persia declared itself independent, in order to ward off allegations of any foreign allegiance. By the end of the 5th century, the Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the teachings of Theodore of Mopsuestia and his followers, many of whom became dissidents after the Councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451). The Persian Church became increasingly opposed to doctrines promoted by those councils, thus furthering the divide between Chalcedonian and Persian currents.

In 486, the Metropolitan Barsauma of Nisibis publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor Theodore of Mopsuestia as a spiritual authority. In 489, when the School of Edessa in Mesopotamia was closed by Byzantine Emperor Zeno for its pro-Nestorian teachings, the school relocated to its original home of Nisibis, becoming again the School of Nisibis, leading to the migration of a wave of Christian dissidents into Persia. The Persian patriarch Babai (497–502) reiterated and expanded upon the church's esteem for Theodore of Mopsuestia.

Now firmly established in Persia, with centers in Nisibis, Ctesiphon, and Gundeshapur, and several metropoleis, the Persian Church began to branch out beyond the Sasanian Empire. However, through the sixth century, the church was frequently beset with internal strife and persecution by Zoroastrians. The infighting led to a schism, which lasted from 521 until around 539 when the issues were resolved. However, immediately afterward Roman-Persian conflict led to the persecution of the church by the Sassanid emperor Khosrow I; this ended in 545. The church survived these trials under the guidance of Patriarch Aba I, who had converted to Christianity from Zoroastrianism.[25]

The church emerged stronger after this period of ordeal, and increased missionary efforts farther afield. Missionaries established dioceses in the Arabian Peninsula and India (the Saint Thomas Christians). They made some advances in Egypt, despite the strong Miaphysite presence there.[26] Missionaries entered Central Asia and had significant success converting local Turkic tribes.

The Anuradhapura Cross discovered in Sri Lanka strongly suggests a strong presence of Nestorian Christianity in Sri Lanka during the 6th century AD according to Humphrey Codrington, who based his claim on a 6th-century manuscript, Christian Topography, that mentions of a community of Persian Christians who were known to reside in Taprobanê (the Ancient Greek name for Sri Lanka).[27][28][29]

Nestorian missionaries were firmly established in China during the early part of the Tang dynasty (618–907); the Chinese source known as the Nestorian Stele records a mission under a Persian proselyte named Alopen as introducing Nestorian Christianity to China in 635. The Jingjiao Documents (also described by The Japanese scholar P. Y. Saeki as "Nestorian Documents") or Jesus Sutras are said to be connected with Alopen.[30]

Following the Arab conquest of Persia, completed in 644, the Persian Church became a dhimmi community under the Rashidun Caliphate. The church and its communities abroad grew larger under the Caliphate. By the 10th century it had 15 metropolitan sees within the Caliphate's territories, and another five elsewhere, including in China and India.[25] After that time, however, Nestorianism went into decline.[disputed – discuss]

Assyrian Church of the East[edit]

In a 1996 article published in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Fellow of the British Academy Sebastian Brock wrote: "the term 'Nestorian Church' has become the standard designation for the ancient oriental church which in the past called itself 'The Church of the East', but which today prefers the fuller title 'The Assyrian Church of the East'. The Common Christological Declaration between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East signed by Pope John Paul II and Mar Dinkha IV underlines the Chalcedonian Christological formulation as the expression of the common faith of these Churches and recognizes the legitimacy of the title Theotokos."[31]

In a 2017 paper, Mar Awa Royel, Bishop of the Assyrian Church, stated the position of that church: "After the Council of Ephesus (431), when Nestorius the patriarch of Constantinople was condemned for his views on the unity of the Godhead and the humanity in Christ, the Church of the East was branded as 'Nestorian' on account of its refusal to anathematize the patriarch."[32]

Several historical records suggest that the Assyrian Church of the East may have been in Sri Lanka between the mid-5th and 6th centuries.[27][28][29]

See also