Transcript

0:00

Today I'm walking the trail from Lake Tekapo up to Ōtehīwai, Mount John. It's a few hours inland from

0:06

Christchurch, New Zealand, and a place I used to come a lot as an undergrad studying astronomy at

0:10

the University of Canterbury. At the top of this hill are some of New Zealand's biggest telescopes,

0:15

and so I wanted to take this chance to talk about one of New Zealand's greatest astronomers.

0:21

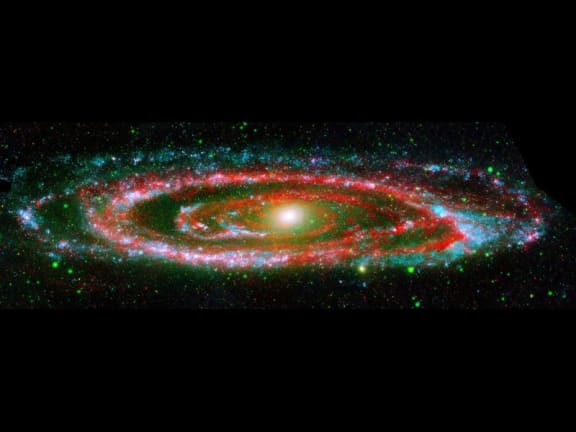

She changed the study of galaxies forever, and she was the first to grasp that galaxies, just

0:27

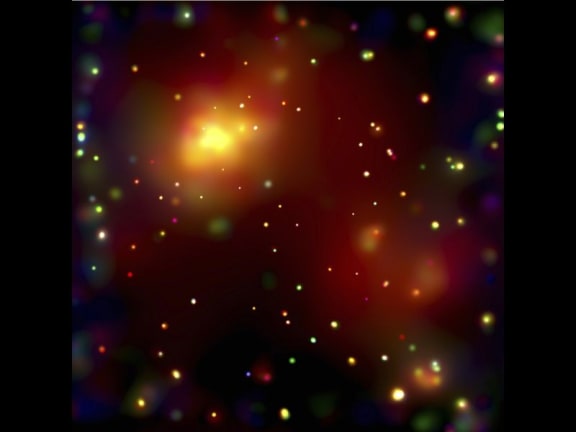

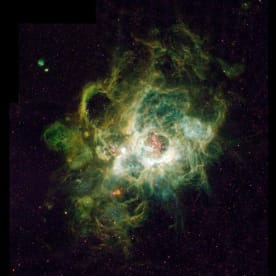

like the stars within them, evolve with time. We are lucky to be able to look at pictures of space,

0:33

like recent ones from the JWST, and know a little bit about what we're looking at. Each

0:39

dot is a galaxy. That's an unfathomable truth, given how large our own galaxy is.

0:46

And much of the science that goes on today, trying to understand these dots, was spearheaded by an

0:52

astronomer from a small New Zealand town. Her name was Beatrice Hill Tinsley. She

0:57

was a trailblazer. And as I walk up this hill today, I'm going to share with you her story.

1:10

Much of what I know about Beatrice I've learned in this book, Bright Star by

1:14

Christine Cole Catley. It was a hard book to find. I got this copy from an old and

1:18

rare bookstore in Otago and it happens to be an old library copy. And it's a shame

1:23

this book isn't more popular because I think that more people should know about Beatrice.

1:29

She was born Beatrice Hill in England in 1941, but came to New Zealand as a baby

1:34

and grew up in New Plymouth. As a young girl, there were a few books about astronomy that

1:39

really fascinated Beatrice. One in particular was Fred Hoyle's The Nature of the Universe,

1:45

which asked questions such as, how was the universe created?

1:51

At age 14, Beatrice was hungry to know more and asked to borrow some physics textbooks

1:56

from her school teacher's bookshelf. She worked through them by herself. A couple of years later,

2:02

that same teacher was injured in a car accident just weeks before the

2:06

school's final exams. Beatrice led her class to study without their teacher,

2:11

and in the final exam, the students got excellent marks.

2:15

This teacher later said that very occasionally, you realize you're dealing with a mind that is

2:20

infinitely superior to your own. Beatrice came into that category. I would call her a

2:26

genius. Beatrice graduated at just age 16 from New Plymouth Girls High School with top marks in her

2:33

year, and she went on to study at the University of Canterbury, the same university I went to.

2:39

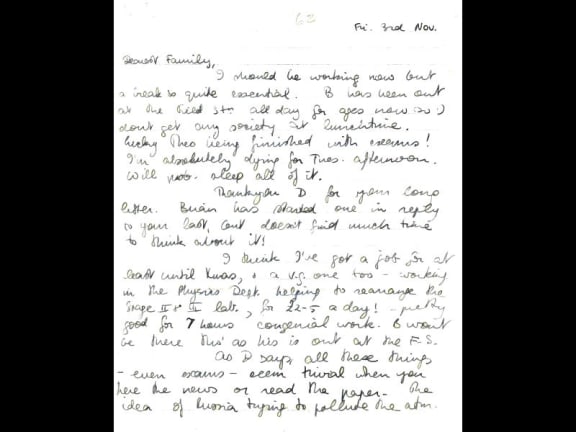

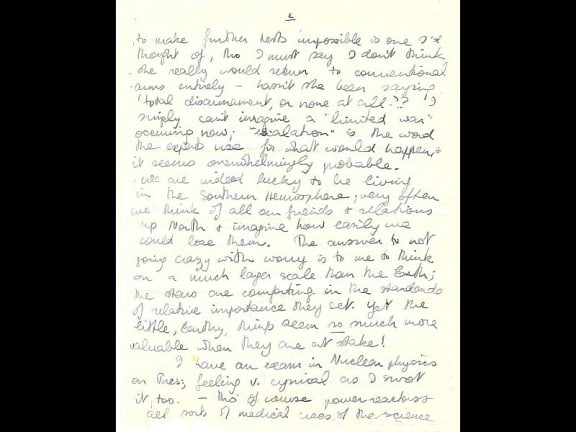

She didn't like rote learning and preferred to teach herself interesting ideas. In a letter

2:44

home from university, she wrote that she was sick of working for

2:48

exams and decided to sit in the back of lectures and work on learning new maths

2:53

rather than listening to the lecturer mumble through calculus she had learned at school.

3:02

During her time at Canterbury, Beatrice decided that she wanted to be a cosmologist,

3:06

but that wasn't really a topic offered at the university at that time. This

3:10

observatory that I'm walking to now wasn't built when Beatrice was a student,

3:14

so she had to do a different research topic for her master's thesis.

3:18

Its title was Theory of the Crystal Field in Neodymium Magnesium Nitrate.

3:23

Even though it wasn't the topic that she was passionate about it gave the added benefit

3:28

of giving her skills using a computer, and she was one of the only people in

3:31

the country who got those kind of skills, and that helped her later in her career.

3:36

She got all A's at university and was the only woman in physics at master's level.

3:41

She also won every academic prize available to her, including the Haydon Prize for Physics,

3:47

which I also won 55 years after her. I do feel connected to Beatrice in lots of little

3:52

ways. And she also won a postgraduate scholarship to continue her studies.

3:58

However, her path after university wasn't so streamlined, and she faced many difficulties

4:03

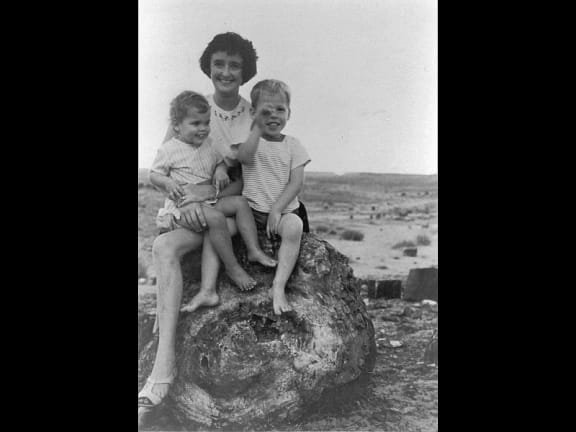

in continuing her studies. She got married at age 20 to fellow physics student Brian Tinsley.

4:09

They moved together to Dallas, Texas. At the time, there were anti nepotism

4:14

laws that prevented both a husband and wife from being employed at the same institution.

4:19

And Beatrice hadn't known this when she got married and felt betrayed. It prevented her

4:24

from continuing her research because Brian was already employed in Dallas. Feeling

4:29

like her potential was languishing, Beatrice took matters into her own hands and decided

4:34

to find somewhere that would let her do a PhD, even if it meant a long commute.

4:39

At the University of Austin, a five hour bus ride away, she managed to convince a professor to give

4:45

her a chance. They told her that most students struggled to complete the program in six years,

4:50

working full time, but she needed to do it part time, splitting her

4:55

time between Dallas and Austin. There is a comment in Catley's book about this time,

4:59

saying that Beatrice used her scholarship to pay for all the travel plus Brian having to

5:04

eat out half the week. This comment disturbed me a little, I guess it's evident that Brian

5:09

wouldn't be expected to cook for himself, and it doesn't sound like Beatrice also

5:14

got the luxury of eating out. It's only a small comment, but it does start to speak

5:18

to the realities of her married life, which she later described as being like a prison for her.

5:24

Regardless, she did very well at her PhD, and she astounded the professors and fellow students by

5:30

scoring the first ever 100 on an exam there. In a letter home to her New Zealand family,

5:36

she described the topic of her thesis by saying, I will be studying a whole

5:41

lot of different theories of cosmology to see which is best able to explain

5:45

the observations made with optical and radio telescopes on different galaxies.

5:50

The theories are based on Einstein's General Relativity. Around the time of starting to write

5:56

up her thesis, Beatrice was thrown a curveball. An unmarried member of her husband's family

6:01

became pregnant and at that time, the baby would need to be adopted out. Beatrice was

6:07

unexpectedly thrust into motherhood, feeling compelled to adopt the baby boy, named Allen.

6:13

She wrote up her thesis while taking care of the baby, and remember how I said most students take

6:18

six years to finish? Well, Beatrice made such impressive progress that she was able to finish

6:23

it in under three years. An examiner at her oral presentation said it was such powerful

6:29

work that they should simply award her the PhD then and there, without asking any questions.

6:35

Although they did continue to ask some, just to meet the formalities. So what was her PhD

6:42

work? Well, we can take a look at her thesis. Its title was Evolution of Galaxies and its

6:47

Significance for Cosmology. In it, she makes some of the first quantitative predictions of

6:53

how galaxies will change over time by looking at how the stars are evolving with time.

6:59

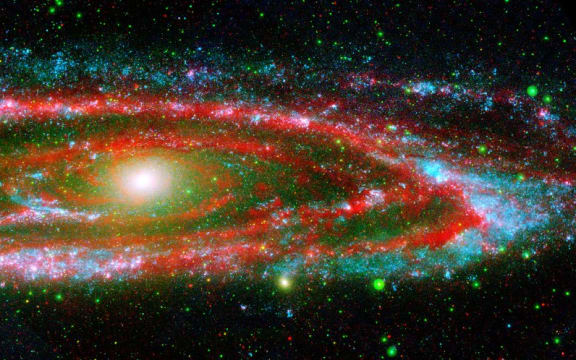

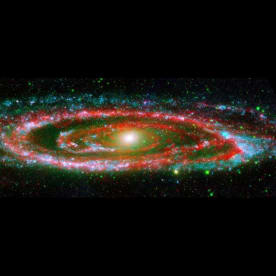

She showed that galaxy evolution is something that can be observed

7:04

and this was to grow into one of the largest subfields within the study of

7:08

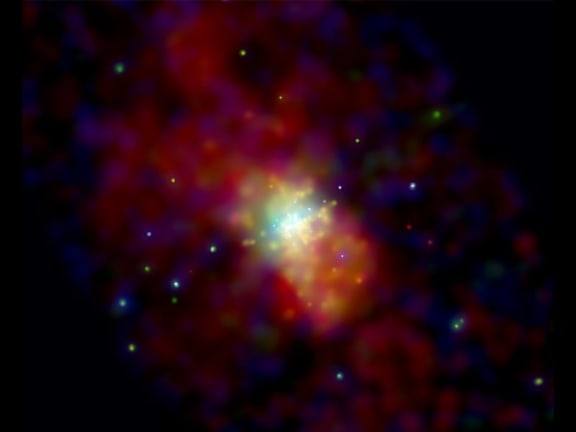

galaxies. She looked at the process of star formation and at how those stars

7:14

would evolve and affect the recycling of dust and gas in the interstellar medium.

7:19

This would shape the fate of the galaxy itself and Beatrice was able to model this

7:24

interconnectedness. Previous to Beatrice's work,

7:28

it was thought that galaxies could be used as standard candles to measure distances in space

7:33

because they didn't change, but Beatrice showed that galaxies could dim with age.

7:39

This had profound effects on how astronomers came up with theories

7:43

of the fate of the universe. Without this insight, the leading theory had been that

7:48

the universe would collapse in a big crunch. Taking into account the changing nature of

7:54

galaxies meant the data now looked more in favor of the universe expanding forever.

8:00

Further observations 30 years later using supernovae instead of galaxies

8:05

as those standard candles were to show that the expansion of the universe was

8:09

in fact speeding up under the influence of what astronomers call dark energy.

8:16

Despite producing a great PhD in record time, Beatrice felt deflated after this achievement.

8:22

She returned to Dallas with no job prospects. She did apply for some

8:26

grants to try and continue her research from home and had short visiting stints at

8:31

places like Caltech. She also adopted a second child, Teresa. From all that I've read so far,

8:37

it is clear that Beatrice loved her children and did all she could to put them first.

8:42

It's also clear that these years post PhD were a real struggle for her personally. When she'd

8:48

moved to Dallas for her husband's job, it had been with an understanding that it would only

8:53

be temporary. But nearly ten years later, she was still waiting for her turn to start her career.

9:00

Everyone that met Beatrice could see her potential and see how bright she was.

9:04

After a long time struggling, she knew that getting a divorce from Brian would

9:08

be the only way that she could shine. She was offered an academic position at Yale

9:13

and wanted to take the children with her, but Brian didn't want her to. To avoid the

9:18

children being fought over in court, she gave way and moved to Yale on her own,

9:23

continuing to visit and help with child care arrangements when she could.

9:27

These aren't the kind of details I usually mention too much in my videos,

9:30

and a case of people splitting up and having children live with one parent is an extremely

9:35

common occurrence. In this case though, Beatrice seems to have received quite a lot of criticism

9:40

on the matter. Her daughter Teresa was later quoted in a New York Times article saying that

9:45

even though it was painful, she was proud that her mom stood her ground and followed her career.

9:51

Moving to Yale, Beatrice finally got to work on the questions that she had

9:55

been inspired to answer as a child, reading Hoyle's book about the origin

9:59

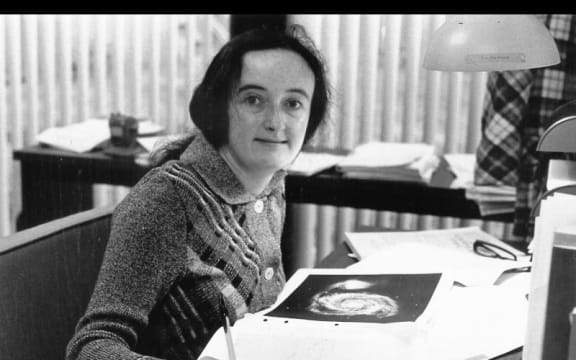

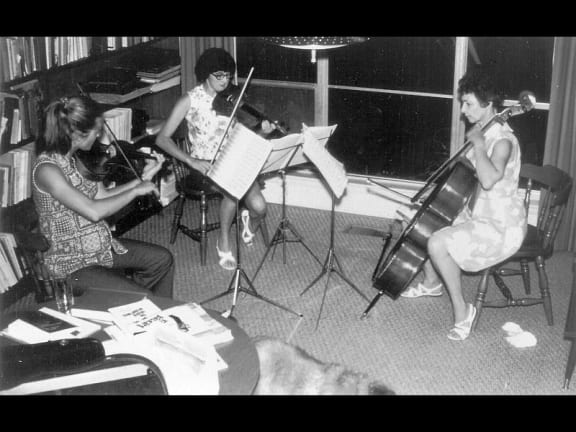

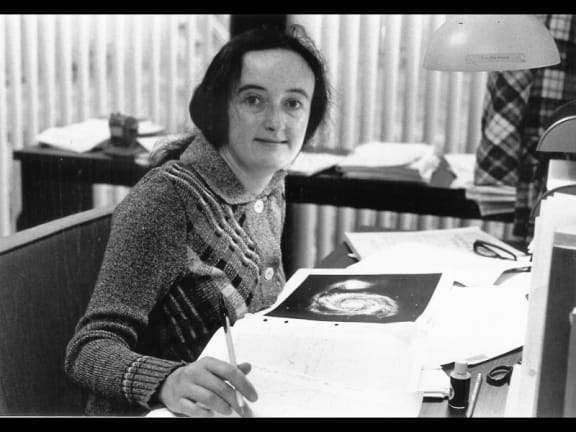

of the universe. One of her papers was featured in Time magazine, which is why she posed for this

10:05

photo shoot at the Blackboard. She published over 100 papers, and looking through them, you can see

10:11

topics like chemical evolution, abundance ratios, metallicity distribution, and even dark matter.

10:18

These are all topics that make up the modern field of galactic astronomy,

10:22

and Beatrice was involved in all of them. Her most impactful paper was published in

10:27

1980 called The Evolution of Stars and Gas in Galaxies. It received thousands of citations

10:34

and its longevity is seen in the fact that papers published this year are still citing it.

10:39

In it, Beatrice describes different aspects of galactic evolution such as

10:43

gaseous inflow and the composition of the interstellar medium. She calls them pieces

10:48

of a jigsaw puzzle that may someday be put together. Another notable achievement of

10:54

Beatrice's was that she organized a big galaxy conference at Yale in 1977, which

11:00

has been described as the single most important galaxy conference in the history of the subject.

11:05

She also became Yale's first female professor of astronomy. But at the height of her career,

11:11

this story took a tragic turn. Just a year after becoming a professor,

11:15

she noticed a bleeding mole on the back of her leg that she had

11:19

previously ignored. She was diagnosed with melanoma and underwent treatment.

11:23

During this time, she still kept busy and looked after Teresa, who had come back to live with her.

11:29

Beatrice continued to work throughout her illness,

11:32

but over the course of a few years, became very sick as treatment failed to save her.

11:37

Her PhD students visited her bedside and she helped them with their work.

11:41

She continued to work on her own research too, and wrote her last paper from her bed

11:46

in the Yale infirmary. She had to learn to use her left hand in order to write

11:50

it out. It was called Chemical Evolution 4, Some Revised General Equations. It was

11:58

submitted 10 days before she died, in March 1981, and it was published after her death.

12:05

It includes calculations showing how to separate living stars from dead remnants,

12:10

and thus making models more consistent.

12:24

That building over there is where the astronomers work today. And inside there's a small library

12:29

with a bound copy of Beatrice's PhD thesis. As an undergrad I got to stay there and

12:34

meet Alan Gilmore and Pam Kilmartin, who, using one of the telescopes here,

12:39

discovered an asteroid in August 1981 that they named Beatrice Tinsley.

12:44

Beatrice's father, Edward Hill, called it a kind of moving tombstone. There are some other

12:49

small traces of her legacy across New Zealand, like this street in Auckland named after her,

12:55

and Mount Tinsley near Queenstown. But still, many New Zealanders don't

12:59

know about Beatrice, and her impact on our understanding of the big questions.

13:03

Beatrice was friends with Vera Rubin, whose work on galaxies provided key evidence for

13:08

the existence of dark matter. I'd like to end with Vera's words about Beatrice. She said,

13:14

Even in her all too brief a life, Beatrice was one of the giants of astronomy in the 20th century.

13:20

There is no telling how much more we might have learned if she had had a longer time to teach us.

13:26

While researching for this video, I saw that Christine Catley's daughter, Nicola Scott,

13:31

is currently driving an attempt to make a movie about Beatrice, based on her mother's book. I

13:36

hope this goes ahead, and that Beatrice's legacy can continue to shine on. Thank you for watching,

13:42

and thank you to my Patreon supporters for making these videos possible.

13:46

A special shout out to today's Patron cat of the day, Thorin.