Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson | |

|---|---|

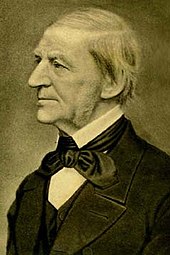

1880 albumen print from a daguerreotype by Josiah Johnson Hawes, c. 1857 | |

| Born | May 25, 1803 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

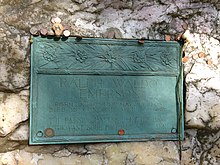

| Died | April 27, 1882 (aged 78) Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Harvard Divinity School |

| Spouse(s) | Ellen Louisa Tucker (m. 1829; died 1831) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | American philosophy |

| School | Transcendentalism |

| Institutions | Harvard College |

Main interests | Individualism, nature, divinity, cultural criticism |

Notable ideas | Self-reliance, transparent eyeball, double consciousness, stream of thought, "Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door" |

show Influences | |

show Influenced | |

| Signature | |

| |

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882),[7] who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society, and his ideology was disseminated through dozens of published essays and more than 1,500 public lectures across the United States.

Emerson gradually moved away from the religious and social beliefs of his contemporaries, formulating and expressing the philosophy of transcendentalism in his 1836 essay "Nature". Following this work, he gave a speech entitled "The American Scholar" in 1837, which Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. considered to be America's "intellectual Declaration of Independence."[8]

Emerson wrote most of his important essays as lectures first and then revised them for print. His first two collections of essays, Essays: First Series (1841) and Essays: Second Series (1844), represent the core of his thinking. They include the well-known essays "Self-Reliance",[9] "The Over-Soul", "Circles", "The Poet", and "Experience." Together with "Nature",[10] these essays made the decade from the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s Emerson's most fertile period. Emerson wrote on a number of subjects, never espousing fixed philosophical tenets, but developing certain ideas such as individuality, freedom, the ability for mankind to realize almost anything, and the relationship between the soul and the surrounding world. Emerson's "nature" was more philosophical than naturalistic: "Philosophically considered, the universe is composed of Nature and the Soul." Emerson is one of several figures who "took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world."[11]

He remains among the linchpins of the American romantic movement,[12] and his work has greatly influenced the thinkers, writers and poets that followed him. "In all my lectures," he wrote, "I have taught one doctrine, namely, the infinitude of the private man."[13] Emerson is also well known as a mentor and friend of Henry David Thoreau, a fellow transcendentalist.[14]

Early life, family, and education[edit]

Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 25, 1803,[15] a son of Ruth Haskins and the Rev. William Emerson, a Unitarian minister. He was named after his mother's brother Ralph and his father's great-grandmother Rebecca Waldo.[16] Ralph Waldo was the second of five sons who survived into adulthood; the others were William, Edward, Robert Bulkeley, and Charles.[17] Three other children—Phoebe, John Clarke, and Mary Caroline—died in childhood.[17] Emerson was entirely of English ancestry, and his family had been in New England since the early colonial period.[18]

Emerson's father died from stomach cancer on May 12, 1811, less than two weeks before Emerson's eighth birthday.[19] Emerson was raised by his mother, with the help of the other women in the family; his aunt Mary Moody Emerson in particular had a profound effect on him.[20] She lived with the family off and on and maintained a constant correspondence with Emerson until her death in 1863.[21]

Emerson's formal schooling began at the Boston Latin School in 1812, when he was nine.[22] In October 1817, at age 14, Emerson went to Harvard College and was appointed freshman messenger for the president, requiring Emerson to fetch delinquent students and send messages to faculty.[23] Midway through his junior year, Emerson began keeping a list of books he had read and started a journal in a series of notebooks that would be called "Wide World".[24] He took outside jobs to cover his school expenses, including as a waiter for the Junior Commons and as an occasional teacher working with his uncle Samuel and aunt Sarah Ripley in Waltham, Massachusetts.[25] By his senior year, Emerson decided to go by his middle name, Waldo.[26] Emerson served as Class Poet; as was custom, he presented an original poem on Harvard's Class Day, a month before his official graduation on August 29, 1821, when he was 18.[27] He did not stand out as a student and graduated in the exact middle of his class of 59 people.[28] In the early 1820s, Emerson was a teacher at the School for Young Ladies (which was run by his brother William). He would next spend two years living in a cabin in the Canterbury section of Roxbury, Massachusetts, where he wrote and studied nature. In his honor, this area is now called Schoolmaster Hill in Boston's Franklin Park.[29]

In 1826, faced with poor health, Emerson went to seek a warmer climate. He first went to Charleston, South Carolina, but found the weather was still too cold.[30] He then went farther south, to St. Augustine, Florida, where he took long walks on the beach and began writing poetry. While in St. Augustine he made the acquaintance of Prince Achille Murat, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. Murat was two years his senior; they became good friends and enjoyed each other's company. The two engaged in enlightening discussions of religion, society, philosophy, and government. Emerson considered Murat an important figure in his intellectual education.[31]

While in St. Augustine, Emerson had his first encounter with slavery. At one point, he attended a meeting of the Bible Society while a slave auction was taking place in the yard outside. He wrote, "One ear therefore heard the glad tidings of great joy, whilst the other was regaled with 'Going, gentlemen, going!'"[32]

Early career[edit]

After Harvard, Emerson assisted his brother William[33] in a school for young women[34] established in their mother's house, after he had established his own school in Chelmsford, Massachusetts; when his brother William[35] went to Göttingen to study law in mid-1824, Ralph Waldo closed the school but continued to teach in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until early 1825.[36] Emerson was accepted into the Harvard Divinity School in late 1824,[36] and was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa in 1828.[37] Emerson's brother Edward,[38] two years younger than he, entered the office of the lawyer Daniel Webster, after graduating from Harvard first in his class. Edward's physical health began to deteriorate, and he soon suffered a mental collapse as well; he was taken to McLean Asylum in June 1828 at age 25. Although he recovered his mental equilibrium, he died in 1834, apparently from long-standing tuberculosis.[39] Another of Emerson's bright and promising younger brothers, Charles, born in 1808, died in 1836, also of tuberculosis,[40] making him the third young person in Emerson's innermost circle to die in a period of a few years.

Emerson met his first wife, Ellen Louisa Tucker, in Concord, New Hampshire, on Christmas Day, 1827, and married her when she was 18 two years later.[41] The couple moved to Boston, with Emerson's mother, Ruth, moving with them to help take care of Ellen, who was already ill with tuberculosis.[42] Less than two years after that, on February 8, 1831, Ellen died, at the age of 20, after uttering her last words: "I have not forgotten the peace and joy".[43] Emerson was heavily affected by her death and visited her grave in Roxbury daily.[44] In a journal entry dated March 29, 1832, he wrote, "I visited Ellen's tomb & opened the coffin".[45]

Boston's Second Church invited Emerson to serve as its junior pastor, and he was ordained on January 11, 1829.[46] His initial salary was $1,200 per year (equivalent to $30,536 in 2021), increasing to $1,400 in July,[47] but with his church role he took on other responsibilities: he was the chaplain of the Massachusetts legislature and a member of the Boston school committee. His church activities kept him busy, though during this period, facing the imminent death of his wife, he began to doubt his own beliefs.

After his wife's death, he began to disagree with the church's methods, writing in his journal in June 1832, "I have sometimes thought that, in order to be a good minister, it was necessary to leave the ministry. The profession is antiquated. In an altered age, we worship in the dead forms of our forefathers".[48] His disagreements with church officials over the administration of the Communion service and misgivings about public prayer eventually led to his resignation in 1832. As he wrote, "This mode of commemorating Christ is not suitable to me. That is reason enough why I should abandon it".[49][50] As one Emerson scholar has pointed out, "Doffing the decent black of the pastor, he was free to choose the gown of the lecturer and teacher, of the thinker not confined within the limits of an institution or a tradition".[51]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Emerson toured Europe in 1833 and later wrote of his travels in English Traits (1856).[52] He left aboard the brig Jasper on Christmas Day, 1832, sailing first to Malta.[53] During his European trip, he spent several months in Italy, visiting Rome, Florence and Venice, among other cities. When in Rome, he met with John Stuart Mill, who gave him a letter of recommendation to meet Thomas Carlyle. He went to Switzerland, and had to be dragged by fellow passengers to visit Voltaire's home in Ferney, "protesting all the way upon the unworthiness of his memory".[54] He then went on to Paris, a "loud modern New York of a place",[54] where he visited the Jardin des Plantes. He was greatly moved by the organization of plants according to Jussieu's system of classification, and the way all such objects were related and connected. As Robert D. Richardson says, "Emerson's moment of insight into the interconnectedness of things in the Jardin des Plantes was a moment of almost visionary intensity that pointed him away from theology and toward science".[55]

Moving north to England, Emerson met William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle in particular was a strong influence on him; Emerson would later serve as an unofficial literary agent in the United States for Carlyle, and in March 1835, he tried to persuade Carlyle to come to America to lecture.[56] The two maintained a correspondence until Carlyle's death in 1881.[57]

Emerson returned to the United States on October 9, 1833, and lived with his mother in Newton, Massachusetts. In October 1834, he moved to Concord, Massachusetts, to live with his step-grandfather, Dr. Ezra Ripley, at what was later named The Old Manse.[58] Given the budding Lyceum movement, which provided lectures on all sorts of topics, Emerson saw a possible career as a lecturer. On November 5, 1833, he made the first of what would eventually be some 1,500 lectures, "The Uses of Natural History", in Boston. This was an expanded account of his experience in Paris.[59] In this lecture, he set out some of his important beliefs and the ideas he would later develop in his first published essay, "Nature":

On January 24, 1835, Emerson wrote a letter to Lydia Jackson proposing marriage.[61] Her acceptance reached him by mail on the 28th. In July 1835, he bought a house on the Cambridge and Concord Turnpike in Concord, Massachusetts, which he named Bush; it is now open to the public as the Ralph Waldo Emerson House.[62] Emerson quickly became one of the leading citizens in the town. He gave a lecture to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the town of Concord on September 12, 1835.[63] Two days later, he married Jackson in her home town of Plymouth, Massachusetts,[64] and moved to the new home in Concord together with Emerson's mother on September 15.[65]

Emerson quickly changed his wife's name to Lidian, and would call her Queenie,[66] and sometimes Asia,[67] and she called him Mr. Emerson.[68] Their children were Waldo, Ellen, Edith, and Edward Waldo Emerson. Edward Waldo Emerson was the father of Raymond Emerson. Ellen was named for his first wife, at Lidian's suggestion.[69]

Emerson was poor when he was at Harvard,[70] but was later able to support his family for much of his life.[71][72] He inherited a fair amount of money after his first wife's death, though he had to file a lawsuit against the Tucker family in 1836 to get it.[72] He received $11,600 in May 1834 (equivalent to $314,863 in 2021),[73] and a further $11,674.49 in July 1837 (equivalent to $279,592 in 2021).[74] In 1834, he considered that he had an income of $1,200 a year from the initial payment of the estate,[71] equivalent to what he had earned as a pastor.

Literary career and transcendentalism[edit]

On September 8, 1836, the day before the publication of Nature, Emerson met with Frederic Henry Hedge, George Putnam, and George Ripley to plan periodic gatherings of other like-minded intellectuals.[75] This was the beginning of the Transcendental Club, which served as a center for the movement. Its first official meeting was held on September 19, 1836.[76] On September 1, 1837, women attended a meeting of the Transcendental Club for the first time. Emerson invited Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Hoar, and Sarah Ripley for dinner at his home before the meeting to ensure that they would be present for the evening get-together.[77] Fuller would prove to be an important figure in transcendentalism.

Emerson anonymously published his first essay, "Nature", on September 9, 1836.[where?] A year later, on August 31, 1837, he delivered his now-famous Phi Beta Kappa address, "The American Scholar",[78] then entitled "An Oration, Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Cambridge"; it was renamed for a collection of essays (which included the first general publication of "Nature") in 1849.[79] Friends urged him to publish the talk, and he did so at his own expense, in an edition of 500 copies, which sold out in a month.[8] In the speech, Emerson declared literary independence in the United States and urged Americans to create a writing style all their own, free from Europe.[80] James Russell Lowell, who was a student at Harvard at the time, called it "an event without former parallel on our literary annals".[81] Another member of the audience, Reverend John Pierce, called it "an apparently incoherent and unintelligible address".[82]

In 1837, Emerson befriended Henry David Thoreau. Though they had likely met as early as 1835, in the fall of 1837, Emerson asked Thoreau, "Do you keep a journal?" The question went on to be a lifelong inspiration for Thoreau.[83] Emerson's own journal was published in 16 large volumes, in the definitive Harvard University Press edition issued between 1960 and 1982. Some scholars consider the journal to be Emerson's key literary work.[84][page needed]

In March 1837, Emerson gave a series of lectures on the philosophy of history at the Masonic Temple in Boston. This was the first time he managed a lecture series on his own, and it was the beginning of his career as a lecturer.[85] The profits from this series of lectures were much larger than when he was paid by an organization to talk, and he continued to manage his own lectures often throughout his lifetime. He eventually gave as many as 80 lectures a year, traveling across the northern United States as far as St. Louis, Des Moines, Minneapolis, and California.[86]

On July 15, 1838,[87] Emerson was invited to Divinity Hall, Harvard Divinity School, to deliver the school's graduation address, which came to be known as the "Divinity School Address". Emerson discounted biblical miracles and proclaimed that, while Jesus was a great man, he was not God: historical Christianity, he said, had turned Jesus into a "demigod, as the Orientals or the Greeks would describe Osiris or Apollo".[88] His comments outraged the establishment and the general Protestant community. He was denounced as an atheist[88] and a poisoner of young men's minds. Despite the roar of critics, he made no reply, leaving others to put forward a defense. He was not invited back to speak at Harvard for another thirty years.[89]

The transcendental group began to publish its flagship journal, The Dial, in July 1840.[90] They planned the journal as early as October 1839, but work did not begin until the first week of 1840.[91] George Ripley was the managing editor.[92] Margaret Fuller was the first editor, having been approached by Emerson after several others had declined the role.[93] Fuller stayed on for about two years, when Emerson took over, using the journal to promote talented young writers including Ellery Channing and Thoreau.[83]

In 1841 Emerson published Essays, his second book, which included the famous essay "Self-Reliance".[94] His aunt called it a "strange medley of atheism and false independence", but it gained favorable reviews in London and Paris. This book, and its popular reception, more than any of Emerson's contributions to date laid the groundwork for his international fame.[95]

In January 1842 Emerson's first son, Waldo, died of scarlet fever.[96] Emerson wrote of his grief in the poem "Threnody" ("For this losing is true dying"),[97] and the essay "Experience". In the same month, William James was born, and Emerson agreed to be his godfather.

Bronson Alcott announced his plans in November 1842 to find "a farm of a hundred acres in excellent condition with good buildings, a good orchard and grounds".[98] Charles Lane purchased a 90-acre (36 ha) farm in Harvard, Massachusetts, in May 1843 for what would become Fruitlands, a community based on Utopian ideals inspired in part by transcendentalism.[99] The farm would run based on a communal effort, using no animals for labor; its participants would eat no meat and use no wool or leather.[100] Emerson said he felt "sad at heart" for not engaging in the experiment himself.[101] Even so, he did not feel Fruitlands would be a success. "Their whole doctrine is spiritual", he wrote, "but they always end with saying, Give us much land and money".[102] Even Alcott admitted he was not prepared for the difficulty in operating Fruitlands. "None of us were prepared to actualize practically the ideal life of which we dreamed. So we fell apart", he wrote.[103] After its failure, Emerson helped buy a farm for Alcott's family in Concord[102] which Alcott named "Hillside".[103]

The Dial ceased publication in April 1844; Horace Greeley reported it as an end to the "most original and thoughtful periodical ever published in this country".[104]

In 1844, Emerson published his second collection of essays, Essays: Second Series. This collection included "The Poet", "Experience", "Gifts", and an essay entitled "Nature", a different work from the 1836 essay of the same name.

Emerson made a living as a popular lecturer in New England and much of the rest of the country. He had begun lecturing in 1833; by the 1850s he was giving as many as 80 lectures per year.[105] He addressed the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and the Gloucester Lyceum, among others. Emerson spoke on a wide variety of subjects, and many of his essays grew out of his lectures. He charged between $10 and $50 for each appearance, bringing him as much as $2,000 in a typical winter lecture season. This was more than his earnings from other sources. In some years, he earned as much as $900 for a series of six lectures, and in another, for a winter series of talks in Boston, he netted $1,600.[106] He eventually gave some 1,500 lectures in his lifetime. His earnings allowed him to expand his property, buying 11 acres (4.5 ha) of land by Walden Pond and a few more acres in a neighboring pine grove. He wrote that he was "landlord and waterlord of 14 acres, more or less".[102]

Emerson was introduced to Indian philosophy through the works of the French philosopher Victor Cousin.[107] In 1845, Emerson's journals show he was reading the Bhagavad Gita and Henry Thomas Colebrooke's Essays on the Vedas.[108] He was strongly influenced by Vedanta, and much of his writing has strong shades of nondualism. One of the clearest examples of this can be found in his essay "The Over-soul":

The central message Emerson drew from his Asian studies was that "the purpose of life was spiritual transformation and direct experience of divine power, here and now on earth."[110][111]

In 1847–48, he toured the British Isles.[112] He also visited Paris between the French Revolution of 1848 and the bloody June Days. When he arrived, he saw the stumps of trees that had been cut down to form barricades in the February riots. On May 21, he stood on the Champ de Mars in the midst of mass celebrations for concord, peace and labor. He wrote in his journal, "At the end of the year we shall take account, & see if the Revolution was worth the trees."[113] The trip left an important imprint on Emerson's later work. His 1856 book English Traits is based largely on observations recorded in his travel journals and notebooks. Emerson later came to see the American Civil War as a "revolution" that shared common ground with the European revolutions of 1848.[114]

In a speech in Concord, Massachusetts on May 3, 1851, Emerson denounced the Fugitive Slave Act:

That summer, he wrote in his diary:

In February 1852 Emerson and James Freeman Clarke and William Henry Channing edited an edition of the works and letters of Margaret Fuller, who had died in 1850.[117] Within a week of her death, her New York editor, Horace Greeley, suggested to Emerson that a biography of Fuller, to be called Margaret and Her Friends, be prepared quickly "before the interest excited by her sad decease has passed away".[118] Published under the title The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli,[119] Fuller's words were heavily censored or rewritten.[120] The three editors were not concerned about accuracy; they believed public interest in Fuller was temporary and that she would not survive as a historical figure.[121] Even so, it was the best-selling biography of the decade and went through thirteen editions before the end of the century.[119]

Walt Whitman published the innovative poetry collection Leaves of Grass in 1855 and sent a copy to Emerson for his opinion. Emerson responded positively, sending Whitman a flattering five-page letter in response.[122] Emerson's approval helped the first edition of Leaves of Grass stir up significant interest[123] and convinced Whitman to issue a second edition shortly thereafter.[124] This edition quoted a phrase from Emerson's letter, printed in gold leaf on the cover: "I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career".[125] Emerson took offense that this letter was made public[126] and later was more critical of the work.[127]

Philosophers Camp at Follensbee Pond – Adirondacks[edit]

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the summer of 1858, would venture into the great wilderness of upstate New York.

Joining him were nine of the most illustrious intellectuals ever to camp out in the Adirondacks to connect with nature: Louis Agassiz, James Russell Lowell, John Holmes, Horatio Woodman, Ebenezer Rockwell Hoar, Jeffries Wyman, Estes Howe, Amos Binney, and William James Stillman. Invited, but unable to make the trip for diverse reasons, were: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Charles Eliot Norton, all members of the Saturday Club (Boston, Massachusetts).[128]

This social club was mostly a literary membership that met the last Saturday of the month at the Boston Parker House Hotel (Omni Parker House). William James Stillman was a painter and founding editor of an art journal called the Crayon. Stillman was born and grew up in Schenectady which was just south of the Adirondack mountains. He would later travel there to paint the wilderness landscape and to fish and hunt. He would share his experiences in this wilderness to the members of the Saturday Club, raising their interest in this unknown region.

James Russell Lowell[129] and William Stillman would lead the effort to organize a trip to the Adirondacks. They would begin their journey on August 2, 1858, traveling by train, steam boat, stagecoach, and canoe guide boats. News that these cultured men were living like "Sacs and Sioux" in the wilderness appeared in newspapers across the nation. This would become known as the "Philosophers Camp".[130]

This event was a landmark in the nineteenth-century intellectual movement, linking nature with art and literature.

Although much has been written over many years by scholars and biographers of Emerson's life, little has been written of what has become known as the "Philosophers Camp" at Follensbee Pond. Yet, his epic poem "Adirondac"[131] reads like a journal of his day to day detailed description of adventures in the wilderness with his fellow members of the Saturday Club. This two week camping excursion (1858 in the Adirondacks) brought him face to face with a true wilderness, something he spoke of in his essay "Nature", published in 1836. He said, "in the wilderness I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages".[132]

Civil War years[edit]

Emerson was staunchly opposed to slavery, but he did not appreciate being in the public limelight and was hesitant about lecturing on the subject. In the years leading up to the Civil War, he did give a number of lectures, however, beginning as early as November 1837.[133] A number of his friends and family members were more active abolitionists than he, at first, but from 1844 on he more actively opposed slavery. He gave a number of speeches and lectures, and welcomed John Brown to his home during Brown's visits to Concord.[134][page needed] He voted for Abraham Lincoln in 1860, but was disappointed that Lincoln was more concerned about preserving the Union than eliminating slavery outright.[135] Once the American Civil War broke out, Emerson made it clear that he believed in immediate emancipation of the slaves.[136]

Around this time, in 1860, Emerson published The Conduct of Life, his seventh collection of essays. It "grappled with some of the thorniest issues of the moment," and "his experience in the abolition ranks is a telling influence in his conclusions."[137] In these essays Emerson strongly embraced the idea of war as a means of national rebirth: "Civil war, national bankruptcy, or revolution, [are] more rich in the central tones than languid years of prosperity."[138]

Emerson visited Washington, D.C, at the end of January 1862. He gave a public lecture at the Smithsonian on January 31, 1862, and declared:, "The South calls slavery an institution ... I call it destitution ... Emancipation is the demand of civilization".[139] The next day, February 1, his friend Charles Sumner took him to meet Lincoln at the White House. Lincoln was familiar with Emerson's work, having previously seen him lecture.[140] Emerson's misgivings about Lincoln began to soften after this meeting.[141] In 1865, he spoke at a memorial service held for Lincoln in Concord: "Old as history is, and manifold as are its tragedies, I doubt if any death has caused so much pain as this has caused, or will have caused, on its announcement."[140] Emerson also met a number of high-ranking government officials, including Salmon P. Chase, the secretary of the treasury; Edward Bates, the attorney general; Edwin M. Stanton, the secretary of war; Gideon Welles, the secretary of the navy; and William Seward, the secretary of state.[142]

On May 6, 1862, Emerson's protégé Henry David Thoreau died of tuberculosis at the age of 44. Emerson delivered his eulogy. He often referred to Thoreau as his best friend,[143] despite a falling-out that began in 1849 after Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.[144] Another friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne, died two years after Thoreau, in 1864. Emerson served as a pallbearer when Hawthorne was buried in Concord, as Emerson wrote, "in a pomp of sunshine and verdure".[145]

He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1864.[146] In 1867, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[147]

Final years and death[edit]

Starting in 1867, Emerson's health began declining; he wrote much less in his journals.[148] Beginning as early as the summer of 1871 or in the spring of 1872, he started experiencing memory problems[149] and suffered from aphasia.[150] By the end of the decade, he forgot his own name at times and, when anyone asked how he felt, he responded, "Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well".[151]

In the spring of 1871, Emerson took a trip on the transcontinental railroad, barely two years after its completion. Along the way and in California he met a number of dignitaries, including Brigham Young during a stopover in Salt Lake City. Part of his California visit included a trip to Yosemite, and while there he met a young and unknown John Muir, a signature event in Muir's career.[152]

Emerson's Concord home caught fire on July 24, 1872. He called for help from neighbors and, giving up on putting out the flames, all tried to save as many objects as possible.[153] The fire was put out by Ephraim Bull Jr., the one-armed son of Ephraim Wales Bull.[154] Donations were collected by friends to help the Emersons rebuild, including $5,000 gathered by Francis Cabot Lowell, another $10,000 collected by LeBaron Russell Briggs, and a personal donation of $1,000 from George Bancroft.[155] Support for shelter was offered as well; though the Emersons ended up staying with family at the Old Manse, invitations came from Anne Lynch Botta, James Elliot Cabot, James T. Fields and Annie Adams Fields.[156] The fire marked an end to Emerson's serious lecturing career; from then on, he would lecture only on special occasions and only in front of familiar audiences.[157]

While the house was being rebuilt, Emerson took a trip to England, continental Europe, and Egypt. He left on October 23, 1872, along with his daughter Ellen,[158] while his wife Lidian spent time at the Old Manse and with friends.[159] Emerson and his daughter Ellen returned to the United States on the ship Olympus along with friend Charles Eliot Norton on April 15, 1873.[160] Emerson's return to Concord was celebrated by the town, and school was canceled that day.[150]

In late 1874, Emerson published an anthology of poetry entitled Parnassus,[161][162] which included poems by Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Julia Caroline Dorr, Jean Ingelow, Lucy Larcom, Jones Very, as well as Thoreau and several others.[163] Originally, the anthology had been prepared as early as the fall of 1871, but it was delayed when the publishers asked for revisions.[164]

The problems with his memory had become embarrassing to Emerson and he ceased his public appearances by 1879. In reply to an invitation to a retirement celebration for Octavius B. Frothingham, he wrote, “I am not in condition to make visits, or take any part in conversation. Old age has rushed on me in the last year, and tied my tongue, and hid my memory, and thus made it a duty to stay at home.” The New York Times quoted his reply and noted that his regrets were read aloud at the celebration.[165] Holmes wrote of the problem saying, "Emerson is afraid to trust himself in society much, on account of the failure of his memory and the great difficulty he finds in getting the words he wants. It is painful to witness his embarrassment at times".[151]

On April 21, 1882, Emerson was found to be suffering from pneumonia.[166] He died six days later. Emerson is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts.[167] He was placed in his coffin wearing a white robe given by the American sculptor Daniel Chester French.[168]

Lifestyle and beliefs[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Individualism |

|---|

Emerson's religious views were often considered radical at the time. He believed that all things are connected to God and, therefore, all things are divine.[169] Critics believed that Emerson was removing the central God figure; as Henry Ware Jr. said, Emerson was in danger of taking away "the Father of the Universe" and leaving "but a company of children in an orphan asylum".[170] Emerson was partly influenced by German philosophy and Biblical criticism.[171] His views, the basis of Transcendentalism, suggested that God does not have to reveal the truth, but that the truth could be intuitively experienced directly from nature.[172] When asked his religious belief, Emerson stated, "I am more of a Quaker than anything else. I believe in the 'still, small voice', and that voice is Christ within us."[173]

Emerson was a supporter of the spread of community libraries in the 19th century, having this to say of them: "Consider what you have in the smallest chosen library. A company of the wisest and wittiest men that could be picked out of all civil countries, in a thousand years, have set in best order the results of their learning and wisdom."[174]

Emerson may have had erotic thoughts about at least one man.[175] During his early years at Harvard, he found himself attracted to a young freshman named Martin Gay about whom he wrote sexually charged poetry.[70][176] He also had a number of romantic interests in various women throughout his life,[70] such as Anna Barker[177] and Caroline Sturgis.[178]

Race and slavery[edit]

Emerson did not become an ardent abolitionist until 1844, though his journals show he was concerned with slavery beginning in his youth, even dreaming about helping to free slaves. In June 1856, shortly after Charles Sumner, a United States Senator, was beaten for his staunch abolitionist views, Emerson lamented that he himself was not as committed to the cause. He wrote, "There are men who as soon as they are born take a bee-line to the axe of the inquisitor. ... Wonderful the way in which we are saved by this unfailing supply of the moral element".[179] After Sumner's attack, Emerson began to speak out about slavery. "I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom", he said at a meeting at Concord that summer.[180] Emerson used slavery as an example of a human injustice, especially in his role as a minister. In early 1838, provoked by the murder of an abolitionist publisher from Alton, Illinois named Elijah Parish Lovejoy, Emerson gave his first public antislavery address. As he said, "It is but the other day that the brave Lovejoy gave his breast to the bullets of a mob, for the rights of free speech and opinion, and died when it was better not to live".[179] John Quincy Adams said the mob-murder of Lovejoy "sent a shock as of any earthquake throughout this continent".[181] However, Emerson maintained that reform would be achieved through moral agreement rather than by militant action. By August 1, 1844, at a lecture in Concord, he stated more clearly his support for the abolitionist movement: "We are indebted mainly to this movement, and to the continuers of it, for the popular discussion of every point of practical ethics".[182]

Emerson is often known as one of the most liberal democratic thinkers of his time who believed that through the democratic process, slavery should be abolished. While being an avid abolitionist who was known for his criticism of the legality of slavery, Emerson struggled with the implications of race.[183] His usual liberal leanings did not clearly translate when it came to believing that all races had equal capability or function, which was a common conception for the period in which he lived.[183] Many critics believe that it was his views on race that inhibited him from becoming an abolitionist earlier in his life and also inhibited him from being more active in the antislavery movement.[184] Much of his early life, he was silent on the topic of race and slavery. Not until he was well into his 30s did Emerson begin to publish writings on race and slavery, and not until he was in his late 40s and 50s did he became known as an antislavery activist.[183]

During his early life, Emerson seemed to develop a hierarchy of races based on faculty to reason or rather, whether African slaves were distinguishably equal to white men based on their ability to reason.[183] In a journal entry written in 1822, Emerson wrote about a personal observation: "It can hardly be true that the difference lies in the attribute of reason. I saw ten, twenty, a hundred large lipped, lowbrowed black men in the streets who, except in the mere matter of language, did not exceed the sagacity of the elephant. Now is it true that these were created superior to this wise animal, and designed to control it? And in comparison with the highest orders of men, the Africans will stand so low as to make the difference which subsists between themselves & the sagacious beasts inconsiderable."[185]

As with many supporters of slavery, during his early years, Emerson seems to have thought that the faculties of African slaves were not equal to those of white slave-owners. But this belief in racial inferiorities did not make Emerson a supporter of slavery.[183] Emerson wrote later that year that "No ingenious sophistry can ever reconcile the unperverted mind to the pardon of Slavery; nothing but tremendous familiarity, and the bias of private interest".[185] Emerson saw the removal of people from their homeland, the treatment of slaves, and the self-seeking benefactors of slaves as gross injustices.[184] For Emerson, slavery was a moral issue, while superiority of the races was an issue he tried to analyze from a scientific perspective based what he believed to be inherited traits.[186]

Emerson saw himself as a man of "Saxon descent". In a speech given in 1835 titled "Permanent Traits of the English National Genius", he said, "The inhabitants of the United States, especially of the Northern portion, are descended from the people of England and have inherited the traits of their national character".[187] He saw direct ties between race based on national identity and the inherent nature of the human being. White Americans who were native-born in the United States and of English ancestry were categorized by him as a separate "race", which he thought had a position of being superior to other nations. His idea of race was based on a shared culture, environment, and history. He believed that native-born Americans of English descent were superior to European immigrants, including the Irish, French, and Germans, and also as being superior to English people from England, whom he considered a close second and the only really comparable group.[183]

Later in his life, Emerson's ideas on race changed when he became more involved in the abolitionist movement while at the same time he began to more thoroughly analyze the philosophical implications of race and racial hierarchies. His beliefs shifted focus to the potential outcomes of racial conflicts. Emerson's racial views were closely related to his views on nationalism and national superiority, which was a common view in the United States at that time. Emerson used contemporary theories of race and natural science to support a theory of race development.[186] He believed that the current political battle and the current enslavement of other races was an inevitable racial struggle, one that would result in the inevitable union of the United States. Such conflicts were necessary for the dialectic of change that would eventually allow the progress of the nation.[186] In much of his later work, Emerson seems to allow the notion that different European races will eventually mix in America. This hybridization process would lead to a superior race that would be to the advantage of the superiority of the United States.[188]

Legacy[edit]

As a lecturer and orator, Emerson—nicknamed the Sage of Concord—became the leading voice of intellectual culture in the United States.[189] James Russell Lowell, editor of the Atlantic Monthly and the North American Review, commented in his book My Study Windows (1871), that Emerson was not only the "most steadily attractive lecturer in America," but also "one of the pioneers of the lecturing system."[190] Herman Melville, who had met Emerson in 1849, originally thought he had "a defect in the region of the heart" and a "self-conceit so intensely intellectual that at first one hesitates to call it by its right name", though he later admitted Emerson was "a great man".[191] Theodore Parker, a minister and transcendentalist, noted Emerson's ability to influence and inspire others: "the brilliant genius of Emerson rose in the winter nights, and hung over Boston, drawing the eyes of ingenuous young people to look up to that great new star, a beauty and a mystery, which charmed for the moment, while it gave also perennial inspiration, as it led them forward along new paths, and towards new hopes".[192]

Emerson's work not only influenced his contemporaries, such as Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau, but would continue to influence thinkers and writers in the United States and around the world down to the present.[193] Notable thinkers who recognize Emerson's influence include Nietzsche and William James, Emerson's godson. There is little disagreement that Emerson was the most influential writer of 19th-century America, though these days he is largely the concern of scholars.[citation needed] Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau and William James were all positive Emersonians, while Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry James were Emersonians in denial—while they set themselves in opposition to the sage, there was no escaping his influence. To T. S. Eliot, Emerson's essays were an "encumbrance".[citation needed] Waldo the Sage was eclipsed from 1914 until 1965, when he returned to shine, after surviving in the work of major American poets like Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens and Hart Crane.[194]

In his book The American Religion, Harold Bloom repeatedly refers to Emerson as "The prophet of the American Religion", which in the context of the book refers to indigenously American religions such as Mormonism and Christian Science, which arose largely in Emerson's lifetime, but also to mainline Protestant churches that Bloom says have become in the United States more gnostic than their European counterparts. In The Western Canon, Bloom compares Emerson to Michel de Montaigne: "The only equivalent reading experience that I know is to reread endlessly in the notebooks and journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American version of Montaigne."[195] Several of Emerson's poems were included in Bloom's The Best Poems of the English Language, although he wrote that none of the poems are as outstanding as the best of Emerson's essays, which Bloom listed as "Self-Reliance", "Circles", "Experience", and "nearly all of Conduct of Life". In his belief that line lengths, rhythms, and phrases are determined by breath, Emerson's poetry foreshadowed the theories of Charles Olson.[196]

Namesakes[edit]

- In May 2006, 168 years after Emerson delivered his "Divinity School Address", Harvard Divinity School announced the establishment of the Emerson Unitarian Universalist Association Professorship.[197] Harvard has also named a building, Emerson Hall (1900), after him.[198]

- The Emerson String Quartet, formed in 1976, took their name from him.[199]

- The Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize is awarded annually to high school students for essays on historical subjects.[200]

- The Emerson Collective is a company devoted to social change.[201]

Selected works[edit]

Collections

- Essays: First Series (1841)

- Essays: Second Series (1844)

- Poems (1847)

- Nature, Addresses and Lectures (1849)

- Representative Men (1850)[202]

- English Traits (1856)

- The Conduct of Life (1860)[203]

- May-Day and Other Pieces (1867)

- Society and Solitude (1870)

- Natural History of the Intellect: the last lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1871)[204]

- Letters and Social Aims (1875)

Individual essays

- "Nature" (1836)

- "Self-Reliance" (Essays: First Series)

- "Compensation" (First Series)

- "The Over-Soul" (First Series)

- "Circles" (First Series)

- "The Poet" (Essays: Second Series)

- "Experience" (Essays: Second Series)

- "Politics" (Second Series)

- "Saadi" in the Atlantic Monthly (1864)

- "The American Scholar"

- "New England Reformers"

- "History"

- "Fate"

Poems

Letters

- Letter to Martin Van Buren

- The Correspondence of Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1834–72[205][206]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Richardson, p. 92.

- ^ "Cousin, Victor (1782–1867)". Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism. Infobase Publishing, 2014.

- ^ Richardson, Robert D. Jr. (2015). Emerson: The Mind on Fire. University of California Press. p. 102.

- ^ Yohannan, John D. (December 15, 1998). "Emerson, Ralph Waldo". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VIII, Fasc. 4. pp. 414–415.

- ^ "Montaigne; or, the Skeptic". rwe.org. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Robert D. Jr. (2015). Emerson: The Mind on Fire. University of California Press. p. 52.

- ^ Ralph Waldo Emerson at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b Richardson, p. 263.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1841). "Self-Reliance". In Charles William Eliot (ed.). Essays and English Traits. Harvard Classics. Vol. 5, with introduction and notes. (56th printing, 1965 ed.). New York: P.F.Collier & Son Corporation. pp. 59–69.

It is for want of self-culture that the idol of Travelling, the idol of Italy, of England, of Egypt, remains for all educated Americans. They who made England, Italy, or Greece venerable in the imagination, did so not by rambling round creation as a moth round a lamp, but by sticking fast where they were, like an axis of the earth. ... The soul is no traveller: the wise man stays at home with the soul, and when his necessities, his duties, on any occasion call him from his house, or into foreign lands, he is at home still and is not gadding abroad from himself. p. 78

- ^ Lewis, Jone Johnson. "Ralph Waldo Emerson – Essays". Transcendentalists.com. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ Lachs, John; Talisse, Robert (2007). American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia. p. 310. ISBN 978-0415939263.

- ^ Gregory Garvey, T. (January 2001). The Emerson Dilemma. ISBN 978-0820322414. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Journal, April 7, 1840.

- ^ "Emerson & Thoreau". Wisdomportal.com. June 6, 2000. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ Richardson, p. 18.

- ^ Allen, p. 5.

- ^ a b Baker, p. 3.

- ^ Cooke, George Willis. Ralph Waldo Emerson. pp. 1, 2.

- ^ McAleer, p. 40.

- ^ Richardson, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Baker, p. 35.

- ^ McAleer, p. 44.

- ^ McAleer, p. 52.

- ^ Richardson, p. 11.

- ^ McAleer, p. 53.

- ^ Richardson, p. 6.

- ^ McAleer, p. 61.

- ^ Buell, p. 13.

- ^ "Ralph Waldo Emerson : The Schoolmaster of Franklin Park" (PDF). Franklinparkcoalition.org. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, p. 72.

- ^ Field, Peter S. (2003). Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Making of a Democratic Intellectual. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-8843-2.

- ^ Richardson, p. 76.

- ^ Richardson, p. 29.

- ^ McAleer, p. 66.

- ^ Richardson, p. 35.

- ^ a b Franklin Park Coalition (May 1980). Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Schoolmaster of Franklin Park (pdf format) (PDF). Boston Parks and Recreation Department. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ Phi Beta Kappa. Massachusetts Alpha (1912). Catalogue of the Harvard Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, Alpha of Massachusetts. Harvard University. p. 20. Retrieved September 11, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Richardson, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Richardson, p. 37.

- ^ Richardson, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Richardson, p. 92.

- ^ McAleer, p. 105.

- ^ Richardson, p. 108.

- ^ Richardson, p. 116.

- ^ Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Volume I. p. 7.

- ^ Richardson, p. 88.

- ^ Richardson, p. 90.

- ^ Sullivan, p. 6.

- ^ Packer, p. 39.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1832). "The Lord's Supper". Uncollected Prose.

- ^ Ferguson, Alfred R. (1964). "Introduction". The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Volume IV. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, p. xi.

- ^ McAleer, p. 132.

- ^ Baker, p. 23.

- ^ a b Richardson, p. 138.

- ^ Richardson, p. 143.

- ^ Richardson, p. 200.

- ^ Packer, p. 40.

- ^ Richardson, p. 182.

- ^ Richardson, p. 154.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1959). Early Lectures 1833–36. Stephen Whicher, ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-22150-5.

- ^ Richardson, p, 190.

- ^ Wilson, Susan (2000). Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 127. ISBN 0-618-05013-2.

- ^ Richardson, p. 206.

- ^ Lydia (Jackson) Emerson was a descendant of Abraham Jackson, one of the original proprietors of Plymouth, who married the daughter of Nathaniel Morton, the longtime Secretary of the Plymouth Colony.

- ^ Richardson, pp. 207–208.

- ^ "Ideas and Thought". Vcu.edu. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ Richardson, p. 193.

- ^ Richardson, p. 192.

- ^ Baker, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Richardson, p. 9.

- ^ a b Richardson, p. 91.

- ^ a b Richardson, 175

- ^ von Frank, p. 91.

- ^ von Frank, p. 125.

- ^ Richardson, p. 245.

- ^ Baker, p. 53.

- ^ Richardson, p. 266.

- ^ Sullivan, p. 13.

- ^ Buell, p. 45.

- ^ Watson, Peter (2005). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 688. ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1.

- ^ Mowat, R. B. (1995). The Victorian Age. London: Senate. p. 83. ISBN 1-85958-161-7.

- ^ Menand, Louis (2001). The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 18. ISBN 0-374-19963-9.

- ^ a b Buell, p. 121.

- ^ Rosenwald

- ^ Richardson, p. 257.

- ^ Richardson, pp. 418–422.

- ^ Packer, p. 73.

- ^ a b Buell, p. 161.

- ^ Sullivan, p. 14.

- ^ Gura, p. 129.

- ^ Von Mehren, p. 120.

- ^ Slater, Abby (1978). In Search of Margaret Fuller. New York: Delacorte Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 0-440-03944-4.

- ^ Gura, pp. 128–129.

- ^ "Essays: First Series (1841)". emersoncentral.com. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Rubel, David, ed. (2008). The Bedside Baccalaureate, Sterling. p. 153.

- ^ Cheever, p. 93.

- ^ McAleer, p. 313.

- ^ Baker, p. 218.

- ^ Packer, p. 148.

- ^ Richardson, p. 381.

- ^ Baker, p. 219.

- ^ a b c Packer, p. 150.

- ^ a b Baker, p. 221.

- ^ Gura, p. 130. An unrelated magazine of the same name was published during several periods through 1929.

- ^ Richardson, p. 418.

- ^ Wilson, R. Jackson (1999). "Emerson as Lecturer". The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Richardson, p. 114.

- ^ Pradhan, Sachin N. (1996). India in the United States: Contribution of India and Indians in the United States of America. Bethesda, Maryland: SP Press International. p. 12.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1841). "The Over-Soul". Essays: First Series.

- ^ Gordon, Robert C. (Robert Cartwright) (2007). Emerson and the light of India : an intellectual history (1st ed.). New Delhi: National Book Trust, India. ISBN 978-8123749341. OCLC 196264051.

- ^ Goldberg, Philip (2013). American Veda : from Emerson and the Beatles to yoga and meditation—how Indian spirituality changed the West (First paperback ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0385521352. OCLC 808413359.

- ^ Buell, p. 31.

- ^ Allen, Gay Wilson (1982). Waldo Emerson. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 512–514.

- ^ Koch, Daniel (2012). Ralph Waldo Emerson in Europe: Class, Race and Revolution in the Making of an American Thinker. I.B.Tauris. pp. 181–195. ISBN 978-1-84885-946-3.

- ^ "VI. The Fugitive Slave Law – Address at Concord. Ralph Waldo Emerson. 1904. The Complete Works". Bartleby.com.

- ^ "Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850". score.rims.k12.ca.us.

- ^ Baker, p. 321.

- ^ Von Mehren, p. 340.

- ^ a b Von Mehren, p. 343.

- ^ Blanchard, Paula (1987). Margaret Fuller: From Transcendentalism to Revolution. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. p. 339. ISBN 0-201-10458-X.

- ^ Von Mehren, p. 342.

- ^ Kaplan, p. 203.

- ^ Callow, Philip (1992). From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. p. 232. ISBN 0-929587-95-2.

- ^ Miller, James E. Jr. (1962). Walt Whitman. New York: Twayne Publishers. p. 27.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books. p. 352. ISBN 0-679-76709-6.

- ^ Callow, Philip (1992). From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. p. 236. ISBN 0-929587-95-2.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books. p. 343. ISBN 0-679-76709-6.

- ^ Emerson, Edward (1918). The Early Years of the Saturday Club 1855–1870. Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ Norton, Charles (1894). Letters of James Russel Lowell. Houghton Library, Harvard University: Harper & Brothers.

- ^ Schlett, James (2015). A Not Too Greatly Changed Eden – The Story of the Philosophers Camp in the Adirondacks. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-5352-6.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1867). May-Day and Other Pieces. Ticknor and Fields.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1905). Nature. The Roycrofters. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Gougeon, p. 38.

- ^ Gougeon

- ^ McAleer, pp. 569–570.

- ^ Richardson, p. 547.

- ^ Gougeon, p. 260.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1860). The Conduct of Life. Boston: Ticknor & Fields. p. 230.

- ^ Baker, p. 433.

- ^ a b Brooks, Atkinson; Mary Oliver (2000). The Essential Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Modern Library. pp. 827, 829. ISBN 978-0-679-78322-0.

- ^ McAleer, p. 570.

- ^ Gougeon, p. 276.

- ^ Richardson, p. 548.

- ^ Packer, p. 193.

- ^ Baker, p. 448.

- ^ "E" (PDF). Members of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences: 1780–2012. American Academy of Arts and Sciences. p. 162. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Gougeon, p. 325.

- ^ Baker, p. 502.

- ^ a b Richardson, p. 569.

- ^ a b McAleer, p. 629.

- ^ Thayer, James Bradley (1884). A Western Journey with Mr. Emerson. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ Richardson, p. 566.

- ^ Baker, p. 504.

- ^ Baker, p. 506.

- ^ McAleer, p. 613.

- ^ Richardson, p. 567.

- ^ Richardson, p. 568.

- ^ Baker, p. 507.

- ^ McAleer, p. 618.

- ^ Wayne, Tiffany K. (2014). Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438109169.

- ^ Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. (1880). "Parnassus: An Anthology of Poetry". Bartleby.com. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Richardson, p. 570.

- ^ Baker, p. 497.

- ^ The New York Times, p. 1, April 23, 1879

- ^ Richardson, p. 572.

- ^ Sullivan, p. 25.

- ^ McAleer, p. 662.

- ^ Richardson, p. 538.

- ^ Buell, p. 165.

- ^ Packer, p. 23.

- ^ Hankins, Barry (2004). The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-313-31848-4.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1932). Uncollected Lectures. Clarence Gohdes, ed. New York. p. 57.

- ^ Murray, Stuart A. P. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN 978-1602397064.

- ^ Shand-Tucci, Douglas (2003). The Crimson Letter. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-312-19896-5.

- ^ Kaplan, p. 248.

- ^ Richardson, p. 326.

- ^ Richardson, p. 327.

- ^ a b McAleer, p. 531.

- ^ Packer, p. 232.

- ^ Richardson, p. 269.

- ^ Lowance, Mason (2000). Against Slavery: An Abolitionist Reader. Penguin Classics. pp. 301–302. ISBN 0-14-043758-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Field, Peter S. (2001). "The Strange Career of Emerson and Race." American Nineteenth Century History 2.1.

- ^ a b Turner, Jack (2008). "Emerson, Slavery, and Citizenship." Raritan 28.2:127–146.

- ^ a b Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1982). The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson. William H. Gilman, ed. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap.

- ^ a b c Finseth, Ian (2005). "Evolution, Cosmopolitanism, and Emerson's Antislavery Politics." American Literature 77.4:729–760.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1959). The Early Lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Harvard University Press. p. 233.

- ^ Field, p. 9.

- ^ Buell, p. 34.

- ^ Bosco and Myerson. Emerson in His Own Time. p. 54

- ^ Sullivan, p. 123.

- ^ Baker, p. 201.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (2013). Delphi Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-909496-86-6.

- ^ New York Times, October 12, 2008.

- ^ Bloom, Harold. The Western Canon. London: Papermac. pp. 147–148.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael (1999). The Lives of the Poets. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0753807453

- ^ "Emerson Unitarian Universalist Association Professorship Established at Harvard Divinity School" (Press release). Harvard Divinity School. May 2006. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ "Emerson Hall Opened" – The Harvard Crimson, January 3, 1906

- ^ "Full Biography 2012–2013 | Emerson String Quartet". Emersonquartet.com. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ "Varsity Academics: Home of the Concord Review, the National Writing Board, and the National History Club". Tcr.org. April 22, 2011. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ "The Quest of Laurene Powell Jobs". Washington Post. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Representative men. Philadelphia: H. ALtemus. Retrieved February 28, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1860). The conduct of life. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. Retrieved February 28, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ York, Maurice; Spaulding, Rick, eds. (2008). Natural History of the Intellect: The Last Lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson (PDF). Chicago: Wrightwood Press. ISBN 978-0980119015.

- ^ Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1883). The Correspondence of Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1834–72. Correspondence.Selections. Boston: James R. Osgood & Company.

- ^ Ireland, Alexander (April 7, 1883). "Review of The Correspondence of Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1834–72". The Academy. 23 (570): 231–233.

References[edit]

- Allen, Gay Wilson (1981). Waldo Emerson. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-74866-8.

- Baker, Carlos (1996). Emerson Among the Eccentrics: A Group Portrait. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-86675-X.

- Bosco, Ronald A.; Myerson, Joel (2006). Emerson Bicentennial Essays. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. ISBN 093490989X.

- Bosco, Ronald A.; Myerson, Joel (2006). The Emerson Brothers: A Fraternal Biography in Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195140361.

- Bosco, Ronald A.; Myerson, Joel (2003). Emerson in His Own Time. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 0-87745-842-1.

- Bosco, Ronald A.; Myerson, Joel (2010). Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Documentary Volume. Detroit: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0787681692.

- Buell, Lawrence (2003). Emerson. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01139-2.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1983). Essays and Lectures. New York: Library of America. ISBN 0-940450-15-1.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1994). Collected Poems and Translations. New York: Library of America. ISBN 0-940450-28-3.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (2010). Selected Journals: 1820–1842. New York: Library of America. ISBN 978-1-59853-067-4.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (2010). Selected Journals: 1841–1877. New York: Library of America. ISBN 978-1-59853-068-1.

- Gougeon, Len (2010). Virtue's Hero: Emerson, Antislavery, and Reform. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3469-1.

- Gura, Philip F. (2007). American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-3477-2.

- Kaplan, Justin (1979). Walt Whitman: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22542-1.

- Koch, Daniel R. (2012). Ralph Waldo Emerson in Europe: Class, Race and Revolution in the Making of an American Thinker. London: I. B. Tauris.

- McAleer, John (1984). Ralph Waldo Emerson: Days of Encounter. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-55341-7.

- Mudge, Jean McClure (ed.) (2015). Mr. Emerson's Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Open Book.

- Myerson, Joel (2000). A Historical Guide to Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512094-9.

- Myerson, Joel; Petrolionus, Sandra Herbert; Walls, Laura Dassaw, eds. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533103-5.

- Packer, Barbara L. (2007). The Transcendentalists. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2958-1.

- Paolucci, Stefano (2008). "Emerson Writes to Clough. A Lost Letter Found in Italy". Emerson Society Papers. 19 (1): 1, 4–5.

- Porte, Joel; Morris, Saundra, eds. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-49946-1.

- Richardson, Robert D. Jr. (1995). Emerson: The Mind on Fire. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08808-5.

- Rosenwald, Lawrence (1988). Emerson and the Art of the Diary. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505333-8.

- Rusk, Ralph Leslie (1957). The Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Slater, Joseph (ed.) (1964). The Correspondence of Emerson and Carlyle. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Stephen, Leslie (1902). . Studies of a Biographer. London: Duckworth. pp. 130–167.

- Sullivan, Wilson (1972). New England Men of Letters. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-788680-8.

- von Frank, Albert J. (1994). An Emerson Chronology. New York: G. K. Hall. ISBN 0-8161-7266-8.

- Von Mehren, Joan (1994). Minerva and the Muse: A Life of Margaret Fuller. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-015-9.

Further reading[edit]

- Long, Roderick (2008). "Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1803–1882)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 142–143. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n89. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Sacks, Kenneth S. (2003). Understanding Emerson: "The American Scholar" and His Struggle for Self-Reliance. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691099828.

Archival sources[edit]

- Ralph Waldo Emerson papers, 1814–1867 (25 boxes) are housed at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University

- Finding aid to Ralph Waldo Emerson letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson additional papers, 1852–1898 (.5 linear feet) are housed at Houghton Library at Harvard University.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson lectures and sermons, c. 1831–1882 (10 linear feet) are housed at Houghton Library at Harvard University.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson letters to Charles King Newcomb, 1842 March 18 – 1, 858 July 25 (22 items) are housed at the Concord Public Library.

External links[edit]

| Library resources about Ralph Waldo Emerson |

| By Ralph Waldo Emerson |

|---|

- The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harvard University Press, Ronald A. Bosco, General Editor; Joel Myerson, Textual Editor

- Works by Ralph Waldo Emerson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ralph Waldo Emerson at Internet Archive

- Works by Ralph Waldo Emerson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson at RWE.org Archived September 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Reading Ralph Waldo Emerson, a blog featuring excerpts from Emerson's journals

- Representative Men from American Studies at the University of Virginia.

- Mark Twain on Ralph Waldo Emerson Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- The Enduring Significance of Emerson's Divinity School Address" – by John Haynes Holmes

- The Living Legacy of Ralph Waldo Emerson Archived March 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine by Rev. Schulman and R. Richardson

- A Tribute to Ralph Waldo Emerson – a hypertext guide, in English and in Italian

- Ralph Waldo Emerson complete Works at the University of Michigan

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Ralph Waldo Emerson" – by Russell Goodman

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Ralph Waldo Emerson" – by Vince Brewton

- Life in the Ralph Waldo Emerson House – slideshow by The New York Times

- A bibliography of books about Emerson

- "Writings of Emerson and Thoreau" from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Ralph Waldo Emerson letters and manuscript. Available online through Lehigh University's I Remain: A Digital Archive of Letters, Manuscripts, and Ephemera.

they said, are attendants on justice, and if the sun in heaven should transgress his path, they would punish him. The poets related that stone walls, and iron swords, and leathern thongs had an occult sympathy with the wrongs of their owners; that the belt which Ajax gave Hector dragged the Trojan hero over the field at the wheels of the car of Achilles, and the sword which Hector gave Ajax was that on whose point Ajax fell. They recorded, that when the Thasians erected a statue to Theagenes, a victor in the games, one of his rivals went to it by night, and endeavoured to throw it down by repeated blows, until at last he moved it from its pedestal, and was crushed to death beneath its fall.

they said, are attendants on justice, and if the sun in heaven should transgress his path, they would punish him. The poets related that stone walls, and iron swords, and leathern thongs had an occult sympathy with the wrongs of their owners; that the belt which Ajax gave Hector dragged the Trojan hero over the field at the wheels of the car of Achilles, and the sword which Hector gave Ajax was that on whose point Ajax fell. They recorded, that when the Thasians erected a statue to Theagenes, a victor in the games, one of his rivals went to it by night, and endeavoured to throw it down by repeated blows, until at last he moved it from its pedestal, and was crushed to death beneath its fall. We are idolaters of the old. We do not believe in the riches of the soul, in its proper eternity and omnipresence. We do not believe there is any force in to-day to rival or recreate that beautiful yesterday. We linger in the ruins of the old tent, where once we had bread and shelter and organs, nor believe that the spirit can feed, cover, and nerve us again. We cannot again find aught so dear, so sweet, so graceful. But we sit and weep in vain. The voice of the Almighty saith, 'Up and onward for evermore!' We cannot stay amid the ruins. Neither will we rely on the new; and so we walk ever with reverted eyes, like those monsters who look backwards.

We are idolaters of the old. We do not believe in the riches of the soul, in its proper eternity and omnipresence. We do not believe there is any force in to-day to rival or recreate that beautiful yesterday. We linger in the ruins of the old tent, where once we had bread and shelter and organs, nor believe that the spirit can feed, cover, and nerve us again. We cannot again find aught so dear, so sweet, so graceful. But we sit and weep in vain. The voice of the Almighty saith, 'Up and onward for evermore!' We cannot stay amid the ruins. Neither will we rely on the new; and so we walk ever with reverted eyes, like those monsters who look backwards.