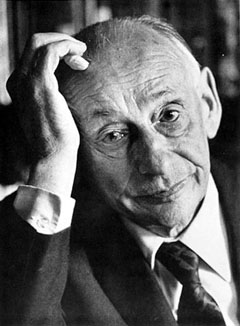

게르숌 숄렘

게르솜 게르하르트 숄렘(Gershom Gerhard Scholem, 1897년 12월 5일 - 1982년 2월 21일)은 독일에서 태어난 유대교 철학자이며 역사가이다. 1923년 영국 위임통치령 팔레스타인으로 이주해 국립도서관의 도서관장을 지냈으며, 이후 카발라를 현대적으로 연구하기 시작해 예루살렘 히브리 대학의 유대교 신비주의의 첫 교수가 된다.

그의 강의록 《유대교 신비주의의 주류 Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism》(1941)와 전기《사바티 제비, 신비주의 메시아 Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah》 (1973)가 유명하다. 그의 강연과 에세이를 모은 《카발라와 기호 On Kabbalah and its Symbolism》(1965)는 유대교 신비주의를 바깥에 알리는 데 지대한 기여를 했다.

그는 1958년 이스라엘 상을 받았고, 1968년 이스라엘 인문 과학 아카데미의 회장으로 뽑혔다.

===

일어

겔쇼 숄렘

겔숀 겔하르트 숄렘 ( גרשם גרהרד שלום Gershom Gerhard Scholem 1897년 12월 5일 - 1982년 2월 21일 )은 독일 출생 의 이스라엘 사상가 . 유대 신비주의( 카바라 )의 세계적 권위로 히브리 대학 교수 를 맡았다. 1968년 에는 이스라엘 문리학사원의 원장으로 선정되었다.

경력 [ 편집 ]

그는 베를린 에서 유대인 가정에서 태어나 자랐다. 아버지는 알투르 쇼렘, 어머니는 베티 힐슈 쇼렘. 화가 였던 아버지는 동화주의자이자 아들이 유대교 에 관심을 가지기를 기뻐하지 않았지만 숄렘은 어머니의 소식없이 정통 랍비 아래에서 히브리어 와 탈무드 를 배울 수 있습니다. 했다.

베를린 대학 에서 수학과 철학과 히브리어 를 전공 . 대학에서는 마르틴 부버 와 발터 벤야민 , 슈 무엘 아그논 , 하임 나프만 비아릭 , 아하드 하암 , 잘만 샤잘 등 면면과 알게 되었다. 1918년 에는 벤야민과 함께 스위스 베른 에 있었지만, 여기서 첫 아내 엘자 브루크하르트를 알게 되었다. 1919년 독일로 돌아와 뮌헨 대학 에서 셈어 연구로 학위를 받았다.

박사 논문 의 테마는, 가장 오래된 카바라 문헌 סֵפֶר הַבָּהִיר (세펠 하 = 바힐 : "광휘의 책")이었다. 시온주의 에 기울여 친구 부버의 영향도 있고, 1923년 에 영령 팔레스타인 으로 이주. 여기서 그는 유대 신비주의 연구에 몰두하여 사서 의 직업을 얻었다. 최종적으로는 이스라엘 국회 도서관의 히브리 유대 문헌 부문의 책임자가 되었다. 나중에 예루살렘 의 히브리 대학 에서 강사로 가르치기 시작했다.

그의 특색은 자연과학의 소양을 살려 카바라 를 과학적으로 가르친 점에 있다. 1933년 에는 히브리 대학의 유대 신비주의 강좌의 초대 교수로 취임, 1965년 에 명예 교수 가 될 때까지 이 지위에 있었다. 칼 구스타프 융 등이 관련된 ' 엘라노스 회의 '에도 참가.

1936년 , 파니아 프로이트와 재혼.

형의 베르너 쇼렘 은 독일의 극좌 조직 <피셔 마슬로프단>의 일원으로 독일 제국 의회 에서는 독일 공산당 선출의 의원이었지만 나중에 의회에서 추방되어 나치 에 의해 암살되었다.

저서 (역서) [ 편집 ]

- '유대주의의 본질' 카와데 서방 신사 , 1972년

- 『유대주의와 서구』 카와데 서방 신사, 1973년

- 『유대교 신비주의』 가와데 서방 신사, 1975년

- 『우리 친구 벤야민』아키라분샤 , 1978년

- 『유대 신비주의』 叢書 유니베르시타스 호세이대학 출판국 , 1985년, 이후 신장판. 별역판

- 「카바라와 그 상징적 표현」

- 베를린에서 예루살렘으로 청춘의 추억

- 연금술과 카발라 작품사 , 2001년

- 『사바타이・츠비전 신비의 메시아』총서 우니베르시타스・호세이대학 출판국, 2009년. 2권 세트

- 공저 외

- 「벤야민의 초상」니시다 서점, 1984년, 회상기를 소수

- 「엘라노스 총서」평범 사 전 9권·별책 1, 1994-95년, 논문수편을 소수

- 발터 벤야민 「벤야민 쇼렘 왕복 서간」

- 한나 아렌트『아렌트=쇼렘 왕복 서간』이와나미 서점 , 2019년

평전 [ 편집 ]

- 데이비드 비아르 '커버러와 반역사 평전 겔쇼 쇼렘' 기무라 미츠지역, 아키라분샤, 1984년

- 스테파누 모제스 '겔숀 숄렘 - 비밀의 역사' - '역사의 천사 로젠츠바이크, 벤야민, 숄렘'

- 고다 마사토 역, 쇼서 우니베르시타스·호세이대학 출판국, 2003년

- Susan A. Handelman "Gelshom Shelem과 Valter Benjamin"- "구제 해석학 Benjamin, Shelem, Revinus

- 고다 마사토, 다나카 아미역, 타카시 우니 베르시타스, 호세이 대학 출판국, 2005

- 우에야마 안토시「부버와 쇼렘 유대의 사상과 그 운명」 이와나미 서점, 2009년

수상 경력 [ 편집 ]

===

=

Gershom Scholem

Gershom Scholem | |

|---|---|

| גרשום שלום | |

Scholem, 1935 | |

| Born | Gerhard Scholem 5 December 1897 |

| Died | 21 February 1982 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | German Israel |

| Alma mater | Frederick William University |

Notable work | Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism |

| Spouse(s) | Fania Freud Scholem |

| Awards | Israel Prize Bialik Prize |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | German philosophy Jewish philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Kabbalah Wissenschaft des Judentums |

| Institutions | Hebrew University of Jerusalem |

Main interests | Philosophy of religion Philosophy of history Mysticism Messianism |

show Influences | |

show Influenced | |

Gershom Scholem (Hebrew: גֵרְשׁׂם שָׁלוֹם) (5 December 1897 – 21 February 1982), was a German-born Israeli philosopher and historian. He is widely regarded as the founder of the modern, academic study of Kabbalah. He was the first professor of Jewish Mysticism at Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[1] His close friends included Theodor Adorno, Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin and Leo Strauss, and selected letters from his correspondence with those philosophers have been published. He was also friendly with the author Shai Agnon and the Talmudic scholar Saul Lieberman.

Scholem is best known for his collection of lectures, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941) and for his biography Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah (1957). His collected speeches and essays, published as On Kabbalah and its Symbolism (1965), helped to spread knowledge of Jewish mysticism among both Jews and non-Jews.

Biography[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Gerhard (Gershom) Scholem was born in Berlin to Arthur Scholem and Betty Hirsch Scholem. His father was a printer. His older brother was the German Communist leader Werner Scholem. He studied Hebrew and Talmud with an Orthodox rabbi.[citation needed]

Scholem met Walter Benjamin in Munich in 1915, when the former was seventeen years old and the latter was twenty-three. They began a lifelong friendship that ended when Benjamin committed suicide in 1940 in the wake of Nazi persecution. Scholem dedicated his book Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (Die jüdische Mystik in ihren Hauptströmungen), based on lectures 1938–1957, to Benjamin. In 1915 Scholem enrolled at the Frederick William University in Berlin (today, Humboldt University), where he studied mathematics, philosophy, and Hebrew. There he met Martin Buber, Shmuel Yosef Agnon, Hayim Nahman Bialik, Ahad Ha'am, and Zalman Shazar.[citation needed]

In Berlin, Scholem befriended Leo Strauss and corresponded with him throughout his life.[2] He studied mathematical logic at the University of Jena under Gottlob Frege. He was in Bern in 1918 with Benjamin when he met Elsa (Escha) Burchhard, who became his first wife. Scholem returned to Germany in 1919, where he received a degree in Semitic languages at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Together with Benjamin he established a fictitious school – the University of Muri.[citation needed]

Scholem wrote his doctoral thesis on the oldest known kabbalistic text, Sefer ha-Bahir. The following year it appeared in book form as "Das Buch Bahir", having been published by his father's publishing house.[citation needed]

Drawn to Zionism and influenced by Buber, he immigrated in 1923 to the British Mandate of Palestine.[3] He became a librarian, heading the Department of Hebrew and Judaica at the National Library. In 1927 he revamped the Dewey Decimal System, making it appropriate for large Judaica collections. Scholem's brother Werner was a member of the ultra-left "Fischer-Maslow Group" and the youngest ever member of the Reichstag, or Weimar Diet, representing the Communist Party of Germany. He was expelled from the party and later murdered by the Nazis during the Third Reich. Unlike his brother, Gershom was vehemently opposed to both Communism and Marxism. In 1936, he married his second wife, Fania Freud. Fania, who had been his student and could read Polish, was helpful in his later research, particularly in regard to Jacob Frank.[citation needed]

In 1946 Scholem was sent by the Hebrew University to search for Jewish books that had been plundered by the Nazis and help return them to their rightful owners. He spent much of the year in Germany and Central Europe as part of this project, known as "Otzrot HaGolah".[citation needed]

Scholem died in Jerusalem, where he is buried next to his wife in the Sanhedria Cemetery. Jürgen Habermas delivered the eulogy.[citation needed]

Academic career[edit]

Scholem became a lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He taught the Kabbalah and mysticism from a scientific point of view and became the first professor of Jewish mysticism at the university in 1933, working in this post until his retirement in 1965, when he became an emeritus professor.

Scholem directly contrasted his historiographical approach on the study of Jewish mysticism with the approach of the 19th-century school of the Wissenschaft des Judentums ("Science of Judaism"), which sought to submit the study of Judaism to the discipline of subjects such as history, philology, and philosophy. According to Jeremy Adler, Scholem's thinking was "both recognizably Jewish and deeply German," and "changed the course of twentieth-century European thought."[4]

Jewish mysticism was seen as Judaism's weakest scholarly link. Scholem told the story of his early research when he was directed to a prominent rabbi who was an expert on Kabbalah. Seeing the rabbi's many books on the subject, Scholem asked about them, only to be told: "This trash? Why would I waste my time reading nonsense like this?" (Robinson 2000, p. 396)

The analysis of Judaism carried out by the Wissenschaft school was flawed in two ways, according to Scholem: It studied Judaism as a dead object rather than as a living organism; and it did not consider the proper foundations of Judaism, the non-rational force that, in Scholem's view, made the religion a living thing.

In Scholem's opinion, the mythical and mystical components were at least as important as the rational ones, and he thought that they, rather than the minutiae of Halakha, were the truly living core of Judaism. In particular, he disagreed with what he considered to be Martin Buber's personalization of Kabbalistic concepts as well as what he argued was an inadequate approach to Jewish history, Hebrew language, and the land of Israel.

In the worldview of Scholem, the research of Jewish mysticism could not be separated from its historical context. Starting from something similar to the Gegengeschichte of Friedrich Nietzsche, he ended up including less normative aspects of Judaism in the public history.

Specifically, Scholem thought that Jewish history could be divided into three periods:

- During the Biblical period, monotheism battles mythology without completely defeating it.

- During the Talmudic period, some of the institutions—for example, the notion of the magical power of the accomplishment of the Sacraments—are removed in favour of the purer concept of the divine transcendence.

- During the medieval period, the impossibility of reconciling the abstract concept of God of ancient Greek philosophy with the personal God of the Bible, led Jewish thinkers, such as Maimonides, to try to eliminate the remaining myths and to modify the figure of the living God. After this time, mysticism, as an effort to find again the essence of the God of their fathers, became more widespread.

The notion of the three periods, with its interactions between rational and irrational elements in Judaism, led Scholem to put forward some controversial arguments. He thought that the 17th century messianic movement, known as Sabbateanism, was developed from the Lurianic Kabbalah. In order to neutralize Sabbateanism, Hasidism had emerged as a Hegelian synthesis. Many of those who joined the Hasidic movement, because they had seen in it an Orthodox congregation, considered it scandalous that their community should be associated with a heretical movement.

In the same way, Scholem produced the hypothesis that the source of the 13th century Kabbalah was a Jewish gnosticism that preceded Christian gnosticism.

The historiographical approach of Scholem also involved a linguistic theory. In contrast to Buber, Scholem believed in the power of the language to invoke supernatural phenomena. In contrast to Walter Benjamin, he put the Hebrew language in a privileged position with respect to other languages, as the only language capable of revealing the divine truth. His special regard for the spiritual potency of the Hebrew language was expressed in his 1926 letter to Franz Rosenzweig regarding his concerns over the "secularization" of Hebrew. Scholem considered the Kabbalists as interpreters of a pre-existent linguistic revelation.

Debate with Hannah Arendt[edit]

In the aftermath of the Adolf Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, Scholem sharply criticised Hannah Arendt's book, Eichmann in Jerusalem and decried her lack of solidarity with the Jewish people (Hebrew: אהבת ישראל "love of one's fellow Jews", ʾaḥəvaṯ ʾiśrāʾēl). Arendt responded that she never loved any collective group, and that she does not love the Jewish people but was only part of them. The bitter fight, which was exchanged in various articles, made Scholem break off ties with Arendt and refuse to forgive her. Scholem wrote to Hans Paeschke that he "knew Hannah Arendt when she was a socialist or half-communist and... when she was a Zionist. I am astounded by her ability to pronounce upon movements in which she was once so deeply engaged, in terms of a distance measured in light years and from such sovereign heights."[5] Interestingly, whereas Arendt felt that Eichmann should be executed, Scholem was opposed, fearing that his execution would serve to alleviate the Germans' collective sense of guilt.[citation needed]

Various other Israeli and Jewish academics also broke off ties with Arendt, claiming that her lack of solidarity with the Jewish people in their time of need was appalling, along with her victimization of various Nazis. Before the Eichmann trial, Scholem also opposed Arendt's interpretation (in letters and the introduction to Illuminations) of Walter Benjamin as a Marxist thinker who predated the New Left. For Scholem, Benjamin had been an essentially religious thinker, whose turn to Marxism had been merely an unfortunate, but inessential and superficial, expedient.[citation needed]

Awards and recognition[edit]

- In 1958, Scholem was awarded the Israel Prize in Jewish studies.[6]

- In 1968, he was elected president of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

- In 1969, he received the Yakir Yerushalayim (Worthy Citizen of Jerusalem) award.[7]

- In 1977, he was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.[8]

Literary influence[edit]

Various stories and essays of the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges were inspired or influenced by Scholem's books.[9] He has also influenced ideas of Umberto Eco, Jacques Derrida, Harold Bloom, Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, and George Steiner.[10] American author Michael Chabon cites Scholem's essay, The Idea of the Golem, as having assisted him in conceiving the Pulitzer-Prize winning book The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay.[11] Chaim Potok's The Book of Lights features a lightly disguised Scholem as "Jacob Keter."[12]

Selected works in English[edit]

- Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 1941

- Jewish Gnosticism, Merkabah Mysticism, and the Talmudic Tradition, 1960

- Arendt and Scholem, "Eichmann in Jerusalem: Exchange of Letters between Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt", in Encounter, 22/1, 1964

- The Messianic Idea in Judaism and other Essays on Jewish Spirituality, trans. 1971

- Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, 1973

- From Berlin to Jerusalem: Memories of My Youth, 1977; trans. Harry Zohn, 1980.

- Kabbalah, Meridian 1974, Plume Books 1987 reissue: ISBN 0-452-01007-1

- Walter Benjamin: the Story of a Friendship, trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1981.

- Origins of the Kabbalah, JPS, 1987 reissue: ISBN 0-691-02047-7

- On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead: Basic Concepts in the Kabbalah, 1997

- The Fullness of Time: Poems, trans. Richard Sieburth

- On Jews and Judaism in Crisis: Selected Essays

- On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism

- Zohar — The Book of Splendor: Basic Readings from the Kabbalah, ed.

- On History and Philosophy of History, in "Naharaim: Journal for German-Jewish Literature and Cultural History", v, 1–2 (2011), pp. 1–7.

- On Franz Rosenzweig and his Familiarity with Kabbala Literature, in "Naharaim: Journal for German-Jewish Literature and Cultural History", vi, 1 (2012), pp. 1–6.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Magid, Shaul, "Gershom Scholem", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2009 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2009/entries/scholem/>.

- ^ Green, Kenneth Hart (1997). "Leo Strauss as a Modern Jewish Thinker" [editor's introduction], in: Leo Strauss, Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity, ed. Green. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791427736. p. 55.

- ^ The Cult Following of Gershom Scholem, Founder of Modern Kabbala Research, Haaretz

- ^ Times Literary Supplement, 10 April 2015

- ^ Aschheim, Steven E. (August 2001). Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem. University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-520-22057-7.

- ^ "Israel Prize recipients in 1958 (in Hebrew)". Israel Prize Official Site. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012.

- ^ "Recipients of Yakir Yerushalayim award (in Hebrew)". Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. City of Jerusalem official website

- ^ "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004 (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv Municipality website" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2007.

- ^ Gourevitch, Philip, "Interview with Jorge Luis Borges (July 1966)", in The Paris review: Interviews, Volume 1, Macmillan, 2006. Cf. p.156. Also see: Ronald Christ (Winter–Spring 1967). "Jorge Luis Borges, The Art of Fiction No. 39". Paris Review.

- ^ Idel, Moshe, "White Letters: From R. Levi Isaac of Berditchev's Views to Postmodern Hermeneutics", Modern Judaism, Volume 26, Number 2, May 2006, pp. 169–192. Oxford University Press

- ^ Kamine, Mark (29 June 2008). "Chasing His Bliss". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Soll, Will (1989). "Chaim Potok's "Book of Lights": Reappropriating Kabbalah in the Nuclear Age". Religion & Literature. 21 (1): 111–135. ISSN 0888-3769.

Further reading[edit]

- Avriel Bar-Levav, On the Absence of a Book from a Library: Gershom Scholem and the Shulhan Arukh. Zutot: Perspectives on Jewish Culture 6 (2009): 71–73

- Engel Amir, Gershom Scholem: An Intellectual Biography, University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- Biale, David. Gershom Scholem: Kabbalah and Counter-History, second ed., 1982.

- Bloom, Harold, ed. Gershom Scholem, 1987.

- Campanini, Saverio, A Case for Sainte-Beuve. Some Remarks on Gershom Scholem's Autobiography, in P. Schäfer – R. Elior (edd.), Creation and Re-Creation in Jewish Thought. Festschrift in Honor of Joseph Dan on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday, Tübingen 2005, pp. 363–400.

- Campanini, Saverio, Some Notes on Gershom Scholem and Christian Kabbalah, in Joseph Dan (ed.), Gershom Scholem in Memoriam, Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought, 21 (2007), pp. 13–33.

- F. Dal Bo, Between sand and stars: Scholem and his translation of Zohar 22a-26b [Ita.], in "Materia Giudaica", VIII, 2, 2003, pp. 297–309 – Analysis of Scholem's translation of Zohar I, 22a-26b

- Jacobson, Eric, Metaphysics of the Profane – The Political Theology of Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem, (Columbia University Press, NY, 2003).

- Lucca, Enrico, Between History and Philosophy of History. Comments on an unpublished Document by Gershom Scholem, in "Naharaim", v, 1–2 (2011), pp. 8–16.

- Lucca, Enrico, Gershom Scholem on Franz Rosenzweig and the Kabbalah. Introduction to the Text, in "Naharaim", vi, 1 (2012), pp. 7–19.

- Mirsky, Yehudah, "Gershom Scholem, 30 Years On", (Jewish Ideas Daily, 2012).

- Heller Wilensky, Sarah, See the letters from Joseph Weiss to Sarah Heller Wilensky in "Joseph Weiss, Letters to Ora" in A. Raoport-Albert (Ed.) Hasidism reappraised. London: Littman Press, 1977.

- Robinson, G. Essential Judaism, Pocket Books, 2000.

External links[edit]

- Audio of Gershom Scholem lecturing on Kabbalah in 1975

- Biography at the Jewish Virtual Library

- "Gershom Scholem & the Study of Mysticism", MyJewishLearning.com

- Biographical page created by Sharon Naveh

- Orthodoxy and the Scholem Moment, by Zvi Leshem

- 1897 births

- 1982 deaths

- 20th-century essayists

- 20th-century German philosophers

- 20th-century Israeli philosophers

- 20th-century Israeli historians

- Corresponding Fellows of the British Academy

- 19th-century German Jews

- German emigrants to Mandatory Palestine

- Hasidic Judaism

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem faculty

- Historians of Jews and Judaism

- Humboldt University of Berlin alumni

- Israel Prize in Jewish studies recipients who were historians

- Israel Prize in Jewish studies recipients who were philosophers

- German essayists

- 20th-century German historians

- German male non-fiction writers

- Israeli essayists

- Israeli philosophers

- Jewish historians

- Jewish philosophers

- Judaic scholars

- Kabbalah

- Librarians at the National Library of Israel

- Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni

- Members of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Philosophers of history

- Philosophers of Judaism

- Philosophers of religion

- Philosophy academics

- Presidents of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- Writers from Berlin

- Zionists

=

한 우정의 역사 - 발터 벤야민을 추억하며

게르숌 숄렘 (지은이),

원제 : Walter Benjamin- die Geschichte einer Freundschaft

정가15,000원

Sales Point : 266

![]() 6.0 100자평(0)리뷰(2)

6.0 100자평(0)리뷰(2)

- 품절 확인일 : 2017-03-08

새상품 eBook 중고상품 (14)

판매알림 신청 출간알림 신청

출간알림 신청 16,500원

16,500원

427쪽

책소개

현대 자본주의 사회의 암울한 미래를 문화적인 측면에서 예측해왔던 발터 벤야민. 그의 문예비평과 <기술복제시대의 예술작품> 등은 현재까지도 그 빛을 발하고 있다. 벤야민은 스스로 '편지'라는 글쓰기 양식을 그것을 쓴 사람의 정신을 표현하는 고유한 것으로 파악했기에 생전 어느 작가보다도 편지를 많이 썼다.

이 책은 벤야민의 '평생 우정'이었던 시오니즘의 대가 게르숌 숄렘(1897~1982)이 벤야민과 25년간 주고받은 편지를 근간으로 쓴 일종의 평전이다. 두 사람의 편지교환을 중심으로 전개되고 있는 이 책을 통해 우리는 벤야민의 생애와 사상적 편린을 간접적으로나마 경험할 수 있다.

벤야민이 유대 정신에 뿌리를 둔 형이상학적 천재였다면, 숄렘은 유대 정신에 바탕을 두고 이른바 '문화적 시오니즘'의 방향에서 유대의 전통을 계승, 발전시키는 데 기여하는 것을 자신의 임무라고 생각했다. 서로에 대한 무한한 신뢰를 바탕으로 서로의 학문적 지향점에 대해 끊임없이 토론하고 논쟁을 벌이는 학자의 자세를 이들의 편지 속에서 엿볼 수 있게 해준다.

목차

두 거대한 정신의 생산적인 교류 | 최성만

머리말

최초의 접촉 1915

자라나는 우정 1916 ~ 17

스위스에서 1918 ~ 19

전쟁이 끝난 뒤 처음 몇 해 1920 ~ 23

거리를 뛰어넘은 신뢰 1924 ~ 23

파리 1927

좌절된 계획 1928 ~ 29

위기와 전환 1930 ~ 32

망명기 1933 ~ 40

부록 1931년 봄, 사적 유물론에 대한 우리의 서신 교환

주(註)

본문에 인용된 벤야민의 저작

발터 벤야민 연보

찾아보기

저자 및 역자소개

게르숌 숄렘 (Gershom Scholem) (지은이)

저자파일

신간알리미 신청

1897년 독일 베를린에서 태어났다. 독일과 스위스에서 수학, 철학, 유대학을 공부하고 1923년 팔레스타인으로 이주한 뒤, 1933년부터 예루살렘 히브리 대학에서 유대 신비주의 분야 교수로 재직했다. 지은책에 <유대 신비주의 주류의 역사>, <유대학>, <유대학의 기본 개념들>, <카발라와 그 상징들에 대하여>, <베를린에서 예루살렘까지. 청년기의 회상>, <신의 신비적 형상에 대하여. 카발라의 기본 개념들에 대한 연구>, <발터 벤야민과 그의 천사>, <사바타이 제비. 신비한 메시아> 등이 있다.

최근작 : <한 우정의 역사> … 총 81종 (모두보기)

최성만 (옮긴이)

저자파일

신간알리미 신청

1956년 전북 익산에서 태어나 서울대 전자공학과를 졸업했으며, 같은 대학교 대학원에서 독어독문학을 전공했다. 독일 베를린 자유대학에서 독문학과 철학을 수학했으며, 1995년 발터 벤야민의 미메시스론에 대한 논문으로 박사학위를 받았다. 저서로 『표현인문학』(공저, 2000), 『발터 벤야민, 기억의 정치학』(2014) 등이 있으며, 역서로는 『예술의 사회학』(공역, 1983), 『전위예술의 새로운 이해』(1986 / 재출간: 『아방가르드의 이론』 2009), 『윤이상의 음악 세계』(공역, 1991), 『한 우정의 역사: 발터 벤야민... 더보기![]()

최근작 : <가족의 재의미화 커뮤니티의 도전>,<발터 벤야민 기억의 정치학>,<표현 인문학> … 총 18종 (모두보기)

Editor Blog

[인문] <독일 비애극의 원천>과 발터 벤야민 읽기 l 2008-11-03

발터 벤야민의 주요 저작 <독일 비애극의 원천>이 드디어 번역, 출간 되었습니다. 얼마 전 <아케이드 프로젝트>가 새롭게 단장해 출간되었고,그 외 주요 저작들 또한'길'과 '새물결' 두 출판사에서 꾸준히 출간되고 있는 가운데 어느덧 쌓여가는 벤야민 도서들을 한 자리에 모아 보았습니다.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

유대인, 숄렘, 벤야민 ![]()

숄렘은 벤야민이 유대인임을 강변한다.

벤야민에 대한 우정과 이해도 한 민족이라는 범위 안에서만 이루어진다.

이스라엘의 팔레스타인 점령이 '필연적'이라는 숄렘은 벤야민이 그와 함께 이스라엘 건국을 돕지 못해 아쉬워 한다.

이 책은 그 뿐이다.  팔레스타인이 '필연적' 선택이었다는 점은 예전부터 내게 분명했고 또 지금도 그렇다네.

팔레스타인이 '필연적' 선택이었다는 점은 예전부터 내게 분명했고 또 지금도 그렇다네.

즉 어떤 시오니즘적 프로그램도 사람들 손을 묶어두지 않았네. (302면)

Gershom Scholem(1897-1982)

- 접기

파고세운닥나무 2008-12-04 공감(2) 댓글(0)![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

영역들은 구분될 수 없다. ![]()

게르숌 숄렘의 <<한 우정의 역사>>를 읽었다.

벤야민은 몹시 고독했고, 친구가 필요했다. 그는 경제적 문제에 시달리면서 최대한 자신의 본모습을 지키려고 노력했다. 그를 구원해준 것은 글쓰기였다. 또한 그것을 합당하게 평가해준 친구들이었다. 그가 사랑에 빠졌던 연인들은 그를 구원해주지 못했다. 그의 근본에는 신학적인 믿음이 자리잡고 있다. 신학적인 믿음을 지상에 나타내는 것, 그것을 온전하게 평가하고 드러내주는 것이 그의 사명이었다. 그는 사명을 꽤 잘 수행했다. 그는 실제로 그렇게 불행하지는 않았을 것이다. 실제 생활에서 벗어나서 근본적 목표를 추구하는 데 자신의 대부분의 삶을 사용했기 때문이다. 숄렘 역시 구원을 추구했으나, 구체적인 유태교의 연구로 자신의 삶을 만들어냈다. 하나의 목표가 이끈 삶은 다르면서도 비슷하다는 것.

이들이 추구한 것은 삶과 글쓰기에서의 도덕성이다. 벤야민은 그의 방식으로, 숄렘도 자신의 방식으로 그것을 행했다. 그들의 도덕성은 "영역들은 구분될 수 없다"는 말 속에서 찾을 수 있다. 그렇다. "영역들은 구분될 수 없다."

pp.163

직관의 대상은 감정 가운데 순수한 것으로 알려져 오는 어떤 내용이 지각될 수 있다는 필연성이다. 이 필연성을 듣는 일을 직관이라고 부른다.

pp.209

더 이상 어떤 새로운 것을 고안해내기보다 오히려 주어진 것, 모범적인 것들을 해석하고 변형시키면서 그 속으로 파고들어가는 것.

pp.257

- 어느 비의(秘儀) 개념 -

역사를 하나의 소송으로 기술하기. 이 소송에서 인간은 말없는 자연의 대리인으로서 창조에 대해, 그리고 약속된 메시아가 오지 않는 데 대해 고소를 제기한다. 그러나 재판정은 미래에 올 것에 대한 증언을 청취하기로 결정한다. 미래를 느끼는 시인, 미래를 보는 조각가, 미래를 듣는 음악가, 미래를 아는 철학자가 등장한다. 비록 모두가 메시아의 도래를 증언함에도 불구하고 그들의 증언은 서로 일치하지 않는다. 판결을 내리지 못하는 재판정은 감히 자신의 우유부단함을 자인하려 하지 않는다. 그리하여 새로운 고소가 끊이지 않고 새로운 증인들도 끊임없이 등장한다. 고문과 수난도 있다. 배심원들은 살아있는 사람들로 이루어져 있는데, 이들은 인간인 원고와 증인들 모두를 똑같이 의심하면서 듣는다. 배심원 자리는 그들의 자손들에게 세습된다. 마침내 배심원들은 자신들의 자리에서 쫓겨날지도 모른다는 불안에 휩싸인다. 마지막에 그들은 모두 도망가버리고, 원고와 증인들만 남게된다.

pp.299

카프카에 대한 연구는 욥기에서 시작하거나 적어도 신의 심판의 가능성에 대한 논의에서 시작해야 하네.

pp.394

자네는 종교와 정치의 혼합이 빚은 마지막 희생자는 아닐지라도 어쩌면 '가장 이해할 수 없는' 희생자가 될 것이라는 말일세....시간이 할 수 있는 것은 지성도 할 수 있다네.

pp.400

나는 사람들이 경우에 따라 레닌처럼 글을 쓸 수 있다는 것을 부정하지는 않네. 나는 다만 사람들이 바로 그와는 정반대를 행하면서 그렇게 하고 있다고 믿는 허구를 공격하는 것이네.....통찰들의 도덕성이 이러한 삶에서는 영락할 수밖에 없기 때문에........이 도덕성이라는 가치는 삶에서 중요한 것....

- 접기

apunk 2007-10-23 공감(2) 댓글(0)