Schmoe, Floyd W. (1895-2001)

By Kit Oldham

Posted 2/25/2010

HistoryLink.org Essay 3876

Floyd Schmoe's life, which more than spanned the twentieth century, was shaped by his love of nature and by his equally passionate commitment to helping those afflicted by war and injustice. A child of the Kansas prairie, Schmoe fell in love with the high mountains and inland seas of the Pacific Northwest where he lived most of his long life. He studied forest and marine ecology, became the first park naturalist at Mount Rainier National Park, headed a science academy, and lectured and wrote on science and nature. A Quaker, Schmoe was a lifelong peace activist -- his FBI file labeled him a "rabid pacifist." He gave up teaching and research to work full time aiding Japanese Americans interned during World War II. As a conscientious objector in World War I he had built homes for war refugees in France and a generation later he built homes for survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his 90s, he traveled to Tashkent and poured concrete to help build a peace park there while leading the effort to create the Seattle Peace Park.

Prairie Home

Floyd Wilfred Schmoe was born in Johnson County, Kansas, on September 21, 1895, the second of Ernest and Minta Schmoe's five children. The family had a small farm about a mile from a rural crossroads in eastern Kansas called Prairie Center. They were members of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers, and the Quaker traditions of nonviolence, social justice, and service to others guided Schmoe throughout his long life. (Not all the family shared his pacifism: Floyd's younger brother Othel "didn't follow the family line, and he joined the Marines" [Elmer Good interview]; some of Floyd's nephews also served in the military.)

For Floyd, a commitment to nonviolence was deeply linked to his love of nature. Even as a child growing up on a farm where butchering livestock and hunting were commonplace, he abhorred the killing of animals. Floyd also preferred wandering the fields and creeks, collecting bugs, snakes, mushrooms, and rocks, to doing his farm chores, which led to tension with his father. Schmoe recalled that it was his mother who encouraged his interest in nature and with whom he shared a love of art and music.

As a young boy, Floyd was fascinated by the one tall tree nearby, a white pine planted in the farmyard by his pioneer grandfather a half century earlier. When he was 12 or so, a chance meeting with a Yale forestry student opened up the possibility of a career working with trees and forests as an alternative to life on the farm. The Yale student's description of Northwest forests, reinforced by his parents' account, a few years later, of the huge trees and high mountains they saw when they visited the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle, inspired Floyd with the idea of someday living and working in the region.

When Floyd was in his teens, his parents sold the farm and moved the family first to the town of Miami in northeast Oklahoma and then to the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas. Floyd attended two years of high school in Miami, staying in a rented room during the school year after the family moved on to Arkansas. He completed high school in Wichita, Kansas, living with an aunt and uncle there. In the high school library, he encountered the nature writing of John Burroughs (1837-1921), which reinforced his desire to pursue forestry as a career.

Seattle and World War

However, instead of doing so immediately, after graduating in 1916 he enrolled at Friends University, a Quaker college in Wichita. It did not offer courses in forestry, Schmoe wrote later in an unpublished biographical sketch (Schmoe Papers, 1/1), "but I stayed on there one year, taking a bit of art and science, in order to remain near a girl I had decided was of equal interest." That was Ruth Pickering. Like Floyd, she came from a Quaker farm family. Floyd and Ruth met in high school. By the end of his year at Friends they were engaged. In the fall of 1917, Floyd moved to Seattle to study forestry at the University of Washington, while Ruth, a talented pianist, remained at Friends University pursuing a degree in music.

Schmoe was captivated by his first glimpses of Puget Sound, from a Great Northern train on his way into Seattle, and of Mount Rainier, which loomed so large above downtown that he initially thought he could hike to it from Seattle in a day. But before he could explore the sound or mountain, America's entry into World War I intervened. Deeply committed to nonviolence, with his draft number coming up, Schmoe applied to work with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), which a group of Quakers had just organized to provide conscientious objectors an opportunity to do relief work in Europe as an alternative to military service.

In May 1918, Schmoe sailed to France with a large group of AFSC volunteers. Soon after arriving, he volunteered to assist a Red Cross ambulance unit and carried stretchers non-stop for 30 hours at the battle of Chateau de Thierry. Notwithstanding many accounts from later years (including an earlier version of this essay), Schmoe was not an ambulance driver and he spent only a few days with the ambulance unit. Most of his 14 months in Europe was devoted to work assisting war refugees. While the fighting continued, he traveled across France helping to build prefab homes and converting army barracks for refugee families to live in. After the Armistice he helped convoy a train carrying medical supplies and food to Poland.

With all the homeward-bound ships full of troops, there was no transportation for civilians and it was not until July 1919 that Schmoe was able to return home. Floyd and Ruth Schmoe were married the next month and immediately set out by train for Seattle and the University of Washington, where Floyd continued his forestry studies and Ruth, who had gotten her music degree, took liberal arts courses. Before the fall semester was over, they were out of money.

Living in Paradise

Schmoe remained fascinated by Mount Rainier, so when a fellow student reported making good money as a climbing guide on Rainier, he applied and was hired as a guide for the following summer. That interview also led to a more immediate, and unique, opportunity for both Floyd and Ruth: serving as winter caretakers for Paradise Inn high on the mountain. The job was not for everyone. The inn was buried under 30 feet of snow and the position was open because the previous two-man crew had abandoned the post after a drunken binge.

Nevertheless, after an arduous climb through the snow from Longmire, the couple spent six contented months alone together in the massive inn until the snow melted and the road reopened in July 1920. Floyd studied the natural surroundings, chopped wood, and made weekly trips to Longmire for supplies and mail, Ruth cooked and played the inn's piano, and together they explored the Paradise Valley on skis. In his memoir of their time on the mountain published 40 years later, Schmoe wrote, "Luckily Ruth and I found no difficulty in employing our time creatively, and the most creative thing we did that year, by all odds, was to start a family" (A Year in Paradise, 49). Their son Ken was born that September.

After working the summer of 1920 as a mountain guide, as he would the following summer, Schmoe continued his forestry classes at the University of Washington, but he was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with their focus on timber as a commodity rather than the wilderness conservation and recreation that he was interested in. Another chance encounter led him to the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse, which offered courses in ecology and recreational forestry. An automobile executive he guided at Mount Rainier told him about the program at Syracuse and helped pay his way there. Schmoe and his family spent a cold school year in Syracuse while he completed his degree. As soon as he graduated in 1922, they returned to Mount Rainier, where he was hired as a park ranger.

For the next six years the family lived in the park, at Paradise in the summer and at Longmire in the winter. Schmoe devoted a lot of his energies to the park naturalist program, preparing exhibits and giving natural history talks to park visitors. By 1924, he had been named Mount Rainier's first full time park naturalist. Even before that, in July 1923, he inaugurated Nature Notes, a newsletter describing the park's wildlife, trees and flowers, and current conditions, writing hundreds of articles over the next six years.

Natural History Educator

Before long, Schmoe expanded his natural history education work beyond the boundaries of the park. His alma mater invited him back to Syracuse to speak about the National Park Service and he was soon making regular cross country trips to lecture on wildlife and conservation. Over the years, he built up a regular series of lecture stops and his natural history writing appeared in a range of publications. In 1925 he published his first book, Our Greatest Mountain, an account of Mount Rainier that "served as an unofficial park handbook" (McIntyre).

Floyd loved the mountain and his job, but by 1928 he and Ruth decided that an isolated ranger's cabin was not the best place to raise their growing family, which now included Esther (born in 1924) and Bill (1927) in addition to Ken. (Their second child, Beth, died within days of her birth in January 1923 when deep snow prevented the doctor from reaching Longmire.) The opportunity to return permanently to Seattle, where they had already built a small house near Lake Washington and where they remained connected to the Quaker Meeting, came when Schmoe was asked to head the newly formed Puget Sound Academy of Science.

Henry Landes, Dean of the University of Washington College of Science, had long wanted to establish a scientific society on campus. In 1928 he asked Schmoe to serve as director of the new academy, which would offer a program of lectures and field trips and produce a monthly publication. The director's salary was not large, and even that minimal pay was dependent on Schmoe's success in signing up enough dues-paying members, which he achieved in large part through a popular children's program. To help make ends meet, Schmoe also worked part-time as an assistant in the forestry school. Despite then having only a bachelor's degree, he eventually became an Instructor of Forest Biology even as he pursued an advanced degree of his own in marine biology, studying at the university's Oceanographic Laboratories (later Friday Harbor Laboratories) in the San Juan Islands.

Island Ecology

While he did so, the family (which now numbered six with the birth of the Schmoes' youngest child, Ruthanna, in 1934) spent several idyllic summers living on a sailboat and a tiny islet. Soon after returning to Seattle, Schmoe had borrowed money to buy and restore an old cutter-rigged sloop, the Linda, that he found rotting in a Lake Union shipyard. He hoped to recoup the money by taking high school students on educational cruises to Alaska, but after one successful season the Depression ended the market for summer cruises. Instead, Schmoe's beloved boat became the family's summer home as he pursued his underwater research.

While cruising the archipelago, the family spotted and fell in love with tiny Flower Island, located just off Lopez Island's Spencer Spit and easily visible from passing ferries. They claimed "squatter's rights" on the island (which did not even appear on the tax rolls) and used it as a base for exploring the San Juan archipelago in the Linda. On the low reef extending from Flower Island Schmoe built an underwater observation post where he spent long hours observing, recording, and photographing the reef ecology. The observation post and his photographic methods became the subject of his 1937 master's thesis.

Not long after he completed his thesis, Schmoe's scientific endeavors took a back seat to his work opposing the outbreak of war and assisting those affected by it. Schmoe was one of several pacifists who gained some notoriety for organizing demonstrations on campus against American involvement in World War II and the lend lease program under which the U.S. provided military equipment to Britain, Russia, China and other countries. He, Ruth, and other area Quakers worked with the AFSC (as he had during the First World War) to collect food and clothing and help resettle Jewish refugees fleeing Europe through Asian ports.

Standing With Japanese Americans

Schmoe was particularly concerned that war with Japan would lead to harsh consequences for Japanese Americans who included, as he frequently pointed out, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and students. When the backlash against the Pearl Harbor attack confirmed his fears, he threw himself into efforts to oppose discriminatory measures and especially the calls to remove Japanese from the community. After Executive Order 9066 authorized the forced removal or internment of all Japanese, including American citizens, on the West Coast, he worked tirelessly to assist those affected by the order.

Schmoe was able to devote himself full time to that work because the Puget Sound Academy had folded and his teaching position in the College of Forestry ended. With enrollment dropping and Schmoe "getting considerable adverse publicity for protests and demonstrations etc. against the war," he told an interviewer years later, "I guess the Dean was quite willing to let me go" (Lewis, 37). By the spring of 1942, Schmoe was heading a new regional office of the AFSC that he and others helped organize in Seattle to assist Japanese facing removal.

One of Schmoe's first projects, working with several fellow Quakers on the faculty, was to help Japanese American students at the University of Washington transfer to schools where they could continue their education (those who moved outside the exclusion zone along the West Coast were not subject to internment). Until the exclusion order took effect in March 1942, several young Japanese Americans worked with Schmoe at the AFSC assisting Japanese families. Two of them, in addition to their own subsequent accomplishments, went on to play important roles in Schmoe's life. Aki Kato Kurose (1925-1998) became a revered Seattle public school teacher, a peace activist, and Schmoe's lifelong friend. Gordon K. Hirabayashi (1918-2012), who unsuccessfully fought the exclusion order all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and won legal redress four decades later, married Esther Schmoe.

As Japanese families from Western Washington were moved into what Schmoe and many others called concentration camps, he and his remaining staff worked with a handful of other local church leaders to assist those in the camps and help look after the property they had been forced to leave behind. For the remainder of the war, Schmoe divided his time between the Seattle AFSC office and internment camps, especially Minidoka in Idaho where most Washington residents had been confined, along with Heart Mountain in Wyoming and Tule Lake in northern California. Ruth accompanied him on trips to the camps and, in Seattle, on visits to Japanese patients at Firland Sanatorium and other medical institutions, whose families were prohibited from visiting them. Schmoe's efforts earned him government surveillance and an FBI investigation, which ultimately concluded that, although he was a "rabid pacifist," visiting and photographing internment camps was not illegal (Schmoe, "From Relocation...").

When the war ended, Schmoe continued working with the AFSC to assist internees as they came home from the camps, sometimes in the face of considerable hostility from former neighbors. He organized work parties to help returning Japanese residents repair homes damaged by neglect or vandalism, replant gardens and farm fields, and replace stolen tools and furnishings. Even as he continued helping Japanese Americans, Schmoe increasingly focused on doing something for the Japanese of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which had been devastated by American atomic bombs.

Houses for Hiroshima

Schmoe abhorred all war, but he considered the bombings, which killed many thousands of civilians, "an atrocity, even in warfare" (Elmer Good interview). Having built houses for those made homeless by World War I and more recently, along with his family, done most of the work on their new house overlooking Lake Washington, he came to the conclusion that building homes for bomb survivors would be more meaningful than merely apologizing. After trying unsuccessfully to convince the national AFSC office to sponsor a home-building project in Hiroshima, Schmoe set out to organize the Hiroshima project on his own.

Finding it difficult to gain permission to work in Japan, he began by moving part way there when a friend offered him a position teaching at the University of Hawaii for the 1946-1947 year. In Hawaii, Schmoe also headed an AFSC program sending food and clothing to Japan. He got his first opportunity to go to Japan himself in 1948, when he brought 250 milk goats to supply milk for orphanages and hospitals as part of the Heifers for Relief project. He visited Hiroshima, viewing the devastation and making contacts that helped him set up a volunteer home-building work camp the following year.

To fund the project that he dubbed "Houses for Hiroshima," Floyd and Ruth mailed an appeal to their Christmas card list, raising several thousand dollars. In the summer of 1949, Schmoe and three other Americans sailed to Japan with building materials and food and medical supplies for the Hiroshima hospital. With the assistance of many Japanese volunteers, and some skilled craftsmen whom they paid, the group built two duplexes to house four homeless families. Hiroshima Mayor Hamai and other city officials actively supported the project, and the four homes were turned over to the city housing authority, which selected the occupants from the 3,800 families who applied.

For the next four summers, Schmoe returned to Japan to build homes for families who had lost theirs in the bombings. Working largely with local volunteers, the project constructed a total of about 20 houses in Hiroshima and another 12 in Nagasaki. Many of the buildings were multi-unit and several were community houses, so altogether Houses for Hiroshima helped to house close to 100 families.

Korea and Sinai

While Schmoe was helping to rebuild Japan, the Korean War was devastating that country. After the Korean Armistice ended the fighting in 1953, the United Nations Korean Relief Agency invited Schmoe to help war refugees there. He set up Houses for Korea, funded by the U.N. and private donations, and selected the Yongin Valley, where fighting in 1950 had destroyed 75 percent of the homes, as the area that the project would assist. From 1953 through 1956, Houses for Korea built homes, dug wells, repaired roads and irrigation systems, and set up a free clinic to provide medical care.

In 1956, Schmoe's attention was drawn to the victims of yet another conflict. When Britain and France bombed Egypt in 1956 following the nationalization of the Suez Canal, 4,000 families in Port Said were displaced. Egyptian President Gamel Nasser planned to resettle them in the Sinai Desert (in part to assert Egyptian control over the area, which Israel had invaded during the fighting). At the urging of Gordon and Esther Hirabayashi, who were working at American University in Cairo, Schmoe formed Wells for Egypt in 1957 to help develop the oasis of El Arish where some of the refugees were settled. He raised money to purchase a pump for the oasis well and nursery plants to start an orchard, and spent several weeks helping plant the orchard.

Writing and Travel

After working in the Sinai, Schmoe flew to Nairobi and traveled by boat back down the Nile to Cairo where Esther and her family were living. The Sinai project marked the end of 17 years of full time, though rarely fully paid, aid work. Schmoe "retired" in 1958 to devote himself to writing. He had already followed Our Greatest Mountain with several more books, including Japan Journey in 1950, describing his 1949 house-building trip. A Year in Paradise, one of his most enduring works, appeared in 1959. It recounts the time Floyd and Ruth spent at Paradise on Mount Rainier in 1920 and their trip around the mountain's Wonderland Trail a few years later when son Ken was a toddler.

Schmoe turned to another of his favorite places in For Love of Some Islands, published in 1964. It centers on a family reunion in 1961 when Floyd, Ruth, and their four children, now accompanied by four spouses and 12 children of their own, returned to their beloved San Juan Islands, interspersing Schmoe's descriptions of and ruminations on the islands' natural history with family adventures, beginning with his construction of a glass-bottomed houseboat from which he and his grandchildren could observe underwater life.

Ruth Schmoe, who had had heart trouble for some years, died in 1969. Despite the loss of the person he called "the greatest thing that ever happened to me" (Lewis, 60), Floyd kept up an active and productive life. Later in 1969, he and his son Ken traveled in Asia. The following year he traveled again, surprising friends when he returned home remarried. He and Tomiko Yamizaki, who had worked for AFSC in Tokyo and years earlier was one of the first Houses for Hiroshima volunteers, met and married in Paris, then traveled through Europe and Africa.

Schmoe continued to travel, write, and undertake new projects well into his 90s. As he did so, his age and accomplishments brought him a degree of celebrity. Responding to a frequently asked question about his longevity, he told one interviewer:

"First, be very careful in the choice of your ancestors. That's one reason I reached 90. And always have something important to do tomorrow" (Angelos).

Peace Parks

In 1987, assisted by other members of Seattle's University Friends Meeting, Schmoe began clearing brambles and trash from a vacant lot near University Bridge across the street from the meeting house to create the Seattle Peace Park. The following summer he traveled with other volunteers from King County to Tashkent (one of Seattle's many sister cities, then part of the Soviet Union, later the capital of Uzbekistan) and at age 92 poured concrete in 100-plus degree heat to help build a peace park there. Later in 1988 Schmoe went to Japan, where he became the second recipient of the Hiroshima Peace Center's Peace Award.

Schmoe used the money from his Peace Award to help fund completion of the Seattle Peace Park, which was dedicated on August 6, 1990, the 45th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing. The small park contains a bronze statue of Sadako Sasaki (1943-1955) of Hiroshima, who died at age 12 of leukemia caused by the bomb, holding a paper crane. Before her death Sadako folded origami paper cranes, attempting to reach 1,000, which according to legend would grant her health. People have been folding cranes ever since as a sign of peace and the statue is often draped with them.

Schmoe's energy and health declined after his son Ken died in a freak accident in December 1996 when a snow-covered tree fell on him. But until the end of his life Schmoe retained his curiosity about the natural and human world and had "something important to do tomorrow" -- usually a long list. Even with all he had accomplished he felt he should do more, telling an interviewer a year before he died:

"Each day I pray ... and I beg forgiveness for my neglect of all those who I could not help" (Barber, "One of History's Voices…").

Floyd Schmoe was 105 when he died in Kenmore on April 20, 2001, leaving 54 living descendants (three surviving children, 15 grandchildren, 34 great-grandchildren, and two great-great-grandchildren) and a legacy of helping others that spanned four continents and more than eighty years.This essay made possible by:

4Culture King County Lodging Tax

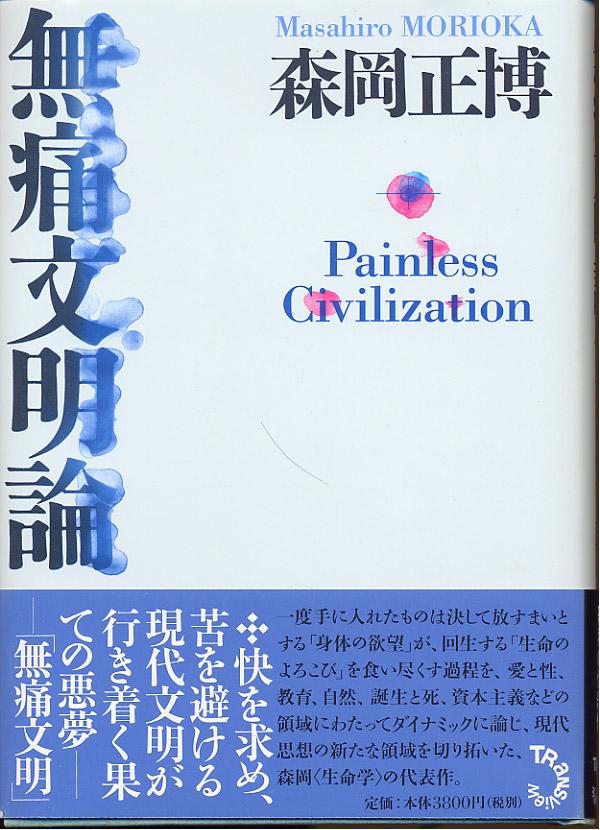

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001), building a house in Hiroshima, Japan, October 4, 1952

Courtesy Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Floyd Schmoe on Hiroshima, interviewed by Elmer Good, Seattle, 1998

Courtesy Densho Digital Archive

Floyd Schmoe on mortality, interviewed by Elmer Good, Seattle, 1998

Courtesy Densho Digital Archive

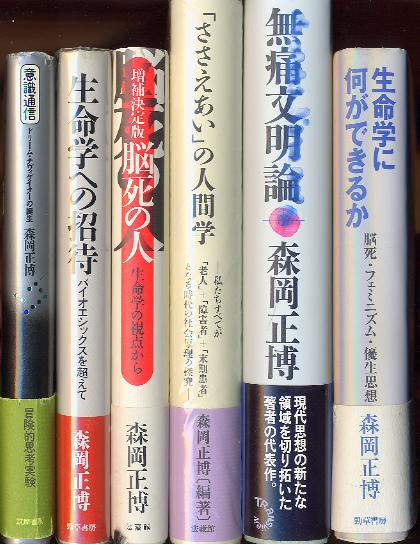

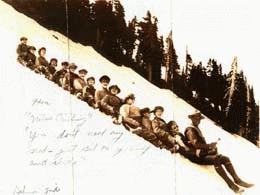

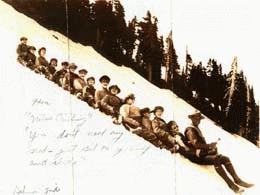

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001), Mount Rainier National Park naturalist, demonstrates "Nature Coasting," 1920s

Courtesy Mount Rainier National Park Archives

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001), first full-time naturalist at Mount Rainier National Park, 1920s

Courtesy Mount Rainier National Park Archives

Paradise, Mount Rainier National Park, July 23, 2005

Photo by Colleen E. O'Connor

Flower Island with Spencer Spit and Lopez Island in background, June 2, 2003

HistoryLink.org Photo by Kit Oldham

Ruins of waiting room entrance station at Minidoka Relocation Center, Minidoka National Monument, Hunt, Idaho, 2004

Photo by Paula Becker

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001)

Courtesy World Peace Project for Children

Sadako Sasaki Peace Child (Daryl Smith, 1990), Seattle Peace Park, February 28, 2010

HistoryLink.org Photo by Kit Oldham

Sources:

Floyd Schmoe, A Year In Paradise (Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1999); Schmoe, For Love of Some Islands (New York: Harper & Row, 1964); Schmoe, "Seattle's Peace Churches and Relocation" in Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress ed. by Roger Daniels et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, [1986], 1991), 117-22; Schmoe, "Construction of an Under-Seas Observation Post and a Method of Under-Water Photography" (master's thesis, University of Washington, 1937); Floyd Wilfred Schmoe Papers, Box 1, Folders 1-3, 33; Box 2, Folders 4-7; Box 8, Folders 23, 25; Box 12, Folders 1, 25-28; Box 13, Folders 9, 14, 17, Accession No. 496-8, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle; "Oral History Interview No. 21," American Friends Service Committee, transcript of Kitty Barragato interview of Floyd Schmoe on February 25, 1989, copy in possession of American Friends Service Committee, Philadelphia; "Floyd Schmoe Interview I & II," Densho Digital Archive, transcripts of Elmer Good interviews of Floyd Schmoe on June 10 and June 22, 1998, copies in possession of Densho Digital Archive, Seattle (www.densho.org); Rose Lewis, "Floyd and Ruth Schmoe: Idealism, Service, Adventure and Commitment in Two Quaker Lives" unpublished typescript dated May 1998, copies in possession of Rose Lewis, Salem, Oregon, and of University Friends Meeting, Seattle; Lewis, notes of interviews with Bill and Lillian Schmoe (July 21-22, 1998) and Inez Schmoe Voorhees (May 19, 1998), copies in possession of Rose Lewis, Salem, OR, and of University Friends Meeting, Seattle; Lynn Thompson, "Vet's Dream: Military Museum," The Seattle Times, June 30, 2004 (http://archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com/web/); Ray Rivera, "Floyd Schmoe's Lifetime of the Heart Remembered," Ibid., April 30, 2001; Marc Ramirez, "A Prime Activist: Creator of Seattle Peace Park is Dead at 105," Ibid., April 24, 2001; Paula Bock, "Floyd Schmoe -- 101 Years Of Peace And Action," Ibid., September 14, 1997; Alex Tizon, "Sharing Hope for Peace," Ibid., March 30, 1997; Constantine Angelos, "At 94, He's Busy Building A Peace Park -- Many Join His Effort," Ibid., July 12, 1990; Mike Barber, "In the Midst of Wars, He Sought Peace and Justice," Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 27, 2001 (http://www.seattlepi.com); Barber, "One of History's Voices for Peace and Justice," Ibid., January 1, 2000; Vanessa Ho, "He Lived in Peace, He Rests in Peace after Tree Falls," Ibid., December 31, 1996; Judi Hunt, "Floyd Schmoe Isn't Ready to Rest until There Is Peace," Ibid., March 18, 1995; Paul Swortz, "Park Emerges from Dump Site: Volunteers Plan Peace Tribute," Ibid., July 24, 1987; Bob McIntyre, Jr., "Floyd W. Schmoe," Mount Rainier National Park Nature Notes website accessed January 22, 2010 (www.nps.gov/archive/mora/notes/schmoe.htm); "Houses for Hiroshima," Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum website accessed January 22, 2010 (www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/exhibit_e/exh0708_e/exh070807_e.html); "About AFSC," American Friends Service Committee website accessed February 18, 2010 (http://www.afsc.org/ht/d/sp/i/267/pid/267); HistoryLink.org, The Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, "Hirabayashi, Gordon K. (b. 1918)" (by David Takami) and "Seattle Tashkent Peace Park in Uzbekistan is dedicated in Tashkent and at Seattle Center on September 12, 1988" (by Priscilla Long) http://www.historylink.org (accessed February 17, 2010).

Note: This essay was revised and substantially expanded on February 25, 2010.

Prairie Home

Floyd Wilfred Schmoe was born in Johnson County, Kansas, on September 21, 1895, the second of Ernest and Minta Schmoe's five children. The family had a small farm about a mile from a rural crossroads in eastern Kansas called Prairie Center. They were members of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers, and the Quaker traditions of nonviolence, social justice, and service to others guided Schmoe throughout his long life. (Not all the family shared his pacifism: Floyd's younger brother Othel "didn't follow the family line, and he joined the Marines" [Elmer Good interview]; some of Floyd's nephews also served in the military.)

For Floyd, a commitment to nonviolence was deeply linked to his love of nature. Even as a child growing up on a farm where butchering livestock and hunting were commonplace, he abhorred the killing of animals. Floyd also preferred wandering the fields and creeks, collecting bugs, snakes, mushrooms, and rocks, to doing his farm chores, which led to tension with his father. Schmoe recalled that it was his mother who encouraged his interest in nature and with whom he shared a love of art and music.

As a young boy, Floyd was fascinated by the one tall tree nearby, a white pine planted in the farmyard by his pioneer grandfather a half century earlier. When he was 12 or so, a chance meeting with a Yale forestry student opened up the possibility of a career working with trees and forests as an alternative to life on the farm. The Yale student's description of Northwest forests, reinforced by his parents' account, a few years later, of the huge trees and high mountains they saw when they visited the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle, inspired Floyd with the idea of someday living and working in the region.

When Floyd was in his teens, his parents sold the farm and moved the family first to the town of Miami in northeast Oklahoma and then to the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas. Floyd attended two years of high school in Miami, staying in a rented room during the school year after the family moved on to Arkansas. He completed high school in Wichita, Kansas, living with an aunt and uncle there. In the high school library, he encountered the nature writing of John Burroughs (1837-1921), which reinforced his desire to pursue forestry as a career.

Seattle and World War

However, instead of doing so immediately, after graduating in 1916 he enrolled at Friends University, a Quaker college in Wichita. It did not offer courses in forestry, Schmoe wrote later in an unpublished biographical sketch (Schmoe Papers, 1/1), "but I stayed on there one year, taking a bit of art and science, in order to remain near a girl I had decided was of equal interest." That was Ruth Pickering. Like Floyd, she came from a Quaker farm family. Floyd and Ruth met in high school. By the end of his year at Friends they were engaged. In the fall of 1917, Floyd moved to Seattle to study forestry at the University of Washington, while Ruth, a talented pianist, remained at Friends University pursuing a degree in music.

Schmoe was captivated by his first glimpses of Puget Sound, from a Great Northern train on his way into Seattle, and of Mount Rainier, which loomed so large above downtown that he initially thought he could hike to it from Seattle in a day. But before he could explore the sound or mountain, America's entry into World War I intervened. Deeply committed to nonviolence, with his draft number coming up, Schmoe applied to work with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), which a group of Quakers had just organized to provide conscientious objectors an opportunity to do relief work in Europe as an alternative to military service.

In May 1918, Schmoe sailed to France with a large group of AFSC volunteers. Soon after arriving, he volunteered to assist a Red Cross ambulance unit and carried stretchers non-stop for 30 hours at the battle of Chateau de Thierry. Notwithstanding many accounts from later years (including an earlier version of this essay), Schmoe was not an ambulance driver and he spent only a few days with the ambulance unit. Most of his 14 months in Europe was devoted to work assisting war refugees. While the fighting continued, he traveled across France helping to build prefab homes and converting army barracks for refugee families to live in. After the Armistice he helped convoy a train carrying medical supplies and food to Poland.

With all the homeward-bound ships full of troops, there was no transportation for civilians and it was not until July 1919 that Schmoe was able to return home. Floyd and Ruth Schmoe were married the next month and immediately set out by train for Seattle and the University of Washington, where Floyd continued his forestry studies and Ruth, who had gotten her music degree, took liberal arts courses. Before the fall semester was over, they were out of money.

Living in Paradise

Schmoe remained fascinated by Mount Rainier, so when a fellow student reported making good money as a climbing guide on Rainier, he applied and was hired as a guide for the following summer. That interview also led to a more immediate, and unique, opportunity for both Floyd and Ruth: serving as winter caretakers for Paradise Inn high on the mountain. The job was not for everyone. The inn was buried under 30 feet of snow and the position was open because the previous two-man crew had abandoned the post after a drunken binge.

Nevertheless, after an arduous climb through the snow from Longmire, the couple spent six contented months alone together in the massive inn until the snow melted and the road reopened in July 1920. Floyd studied the natural surroundings, chopped wood, and made weekly trips to Longmire for supplies and mail, Ruth cooked and played the inn's piano, and together they explored the Paradise Valley on skis. In his memoir of their time on the mountain published 40 years later, Schmoe wrote, "Luckily Ruth and I found no difficulty in employing our time creatively, and the most creative thing we did that year, by all odds, was to start a family" (A Year in Paradise, 49). Their son Ken was born that September.

After working the summer of 1920 as a mountain guide, as he would the following summer, Schmoe continued his forestry classes at the University of Washington, but he was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with their focus on timber as a commodity rather than the wilderness conservation and recreation that he was interested in. Another chance encounter led him to the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse, which offered courses in ecology and recreational forestry. An automobile executive he guided at Mount Rainier told him about the program at Syracuse and helped pay his way there. Schmoe and his family spent a cold school year in Syracuse while he completed his degree. As soon as he graduated in 1922, they returned to Mount Rainier, where he was hired as a park ranger.

For the next six years the family lived in the park, at Paradise in the summer and at Longmire in the winter. Schmoe devoted a lot of his energies to the park naturalist program, preparing exhibits and giving natural history talks to park visitors. By 1924, he had been named Mount Rainier's first full time park naturalist. Even before that, in July 1923, he inaugurated Nature Notes, a newsletter describing the park's wildlife, trees and flowers, and current conditions, writing hundreds of articles over the next six years.

Natural History Educator

Before long, Schmoe expanded his natural history education work beyond the boundaries of the park. His alma mater invited him back to Syracuse to speak about the National Park Service and he was soon making regular cross country trips to lecture on wildlife and conservation. Over the years, he built up a regular series of lecture stops and his natural history writing appeared in a range of publications. In 1925 he published his first book, Our Greatest Mountain, an account of Mount Rainier that "served as an unofficial park handbook" (McIntyre).

Floyd loved the mountain and his job, but by 1928 he and Ruth decided that an isolated ranger's cabin was not the best place to raise their growing family, which now included Esther (born in 1924) and Bill (1927) in addition to Ken. (Their second child, Beth, died within days of her birth in January 1923 when deep snow prevented the doctor from reaching Longmire.) The opportunity to return permanently to Seattle, where they had already built a small house near Lake Washington and where they remained connected to the Quaker Meeting, came when Schmoe was asked to head the newly formed Puget Sound Academy of Science.

Henry Landes, Dean of the University of Washington College of Science, had long wanted to establish a scientific society on campus. In 1928 he asked Schmoe to serve as director of the new academy, which would offer a program of lectures and field trips and produce a monthly publication. The director's salary was not large, and even that minimal pay was dependent on Schmoe's success in signing up enough dues-paying members, which he achieved in large part through a popular children's program. To help make ends meet, Schmoe also worked part-time as an assistant in the forestry school. Despite then having only a bachelor's degree, he eventually became an Instructor of Forest Biology even as he pursued an advanced degree of his own in marine biology, studying at the university's Oceanographic Laboratories (later Friday Harbor Laboratories) in the San Juan Islands.

Island Ecology

While he did so, the family (which now numbered six with the birth of the Schmoes' youngest child, Ruthanna, in 1934) spent several idyllic summers living on a sailboat and a tiny islet. Soon after returning to Seattle, Schmoe had borrowed money to buy and restore an old cutter-rigged sloop, the Linda, that he found rotting in a Lake Union shipyard. He hoped to recoup the money by taking high school students on educational cruises to Alaska, but after one successful season the Depression ended the market for summer cruises. Instead, Schmoe's beloved boat became the family's summer home as he pursued his underwater research.

While cruising the archipelago, the family spotted and fell in love with tiny Flower Island, located just off Lopez Island's Spencer Spit and easily visible from passing ferries. They claimed "squatter's rights" on the island (which did not even appear on the tax rolls) and used it as a base for exploring the San Juan archipelago in the Linda. On the low reef extending from Flower Island Schmoe built an underwater observation post where he spent long hours observing, recording, and photographing the reef ecology. The observation post and his photographic methods became the subject of his 1937 master's thesis.

Not long after he completed his thesis, Schmoe's scientific endeavors took a back seat to his work opposing the outbreak of war and assisting those affected by it. Schmoe was one of several pacifists who gained some notoriety for organizing demonstrations on campus against American involvement in World War II and the lend lease program under which the U.S. provided military equipment to Britain, Russia, China and other countries. He, Ruth, and other area Quakers worked with the AFSC (as he had during the First World War) to collect food and clothing and help resettle Jewish refugees fleeing Europe through Asian ports.

Standing With Japanese Americans

Schmoe was particularly concerned that war with Japan would lead to harsh consequences for Japanese Americans who included, as he frequently pointed out, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and students. When the backlash against the Pearl Harbor attack confirmed his fears, he threw himself into efforts to oppose discriminatory measures and especially the calls to remove Japanese from the community. After Executive Order 9066 authorized the forced removal or internment of all Japanese, including American citizens, on the West Coast, he worked tirelessly to assist those affected by the order.

Schmoe was able to devote himself full time to that work because the Puget Sound Academy had folded and his teaching position in the College of Forestry ended. With enrollment dropping and Schmoe "getting considerable adverse publicity for protests and demonstrations etc. against the war," he told an interviewer years later, "I guess the Dean was quite willing to let me go" (Lewis, 37). By the spring of 1942, Schmoe was heading a new regional office of the AFSC that he and others helped organize in Seattle to assist Japanese facing removal.

One of Schmoe's first projects, working with several fellow Quakers on the faculty, was to help Japanese American students at the University of Washington transfer to schools where they could continue their education (those who moved outside the exclusion zone along the West Coast were not subject to internment). Until the exclusion order took effect in March 1942, several young Japanese Americans worked with Schmoe at the AFSC assisting Japanese families. Two of them, in addition to their own subsequent accomplishments, went on to play important roles in Schmoe's life. Aki Kato Kurose (1925-1998) became a revered Seattle public school teacher, a peace activist, and Schmoe's lifelong friend. Gordon K. Hirabayashi (1918-2012), who unsuccessfully fought the exclusion order all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and won legal redress four decades later, married Esther Schmoe.

As Japanese families from Western Washington were moved into what Schmoe and many others called concentration camps, he and his remaining staff worked with a handful of other local church leaders to assist those in the camps and help look after the property they had been forced to leave behind. For the remainder of the war, Schmoe divided his time between the Seattle AFSC office and internment camps, especially Minidoka in Idaho where most Washington residents had been confined, along with Heart Mountain in Wyoming and Tule Lake in northern California. Ruth accompanied him on trips to the camps and, in Seattle, on visits to Japanese patients at Firland Sanatorium and other medical institutions, whose families were prohibited from visiting them. Schmoe's efforts earned him government surveillance and an FBI investigation, which ultimately concluded that, although he was a "rabid pacifist," visiting and photographing internment camps was not illegal (Schmoe, "From Relocation...").

When the war ended, Schmoe continued working with the AFSC to assist internees as they came home from the camps, sometimes in the face of considerable hostility from former neighbors. He organized work parties to help returning Japanese residents repair homes damaged by neglect or vandalism, replant gardens and farm fields, and replace stolen tools and furnishings. Even as he continued helping Japanese Americans, Schmoe increasingly focused on doing something for the Japanese of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which had been devastated by American atomic bombs.

Houses for Hiroshima

Schmoe abhorred all war, but he considered the bombings, which killed many thousands of civilians, "an atrocity, even in warfare" (Elmer Good interview). Having built houses for those made homeless by World War I and more recently, along with his family, done most of the work on their new house overlooking Lake Washington, he came to the conclusion that building homes for bomb survivors would be more meaningful than merely apologizing. After trying unsuccessfully to convince the national AFSC office to sponsor a home-building project in Hiroshima, Schmoe set out to organize the Hiroshima project on his own.

Finding it difficult to gain permission to work in Japan, he began by moving part way there when a friend offered him a position teaching at the University of Hawaii for the 1946-1947 year. In Hawaii, Schmoe also headed an AFSC program sending food and clothing to Japan. He got his first opportunity to go to Japan himself in 1948, when he brought 250 milk goats to supply milk for orphanages and hospitals as part of the Heifers for Relief project. He visited Hiroshima, viewing the devastation and making contacts that helped him set up a volunteer home-building work camp the following year.

To fund the project that he dubbed "Houses for Hiroshima," Floyd and Ruth mailed an appeal to their Christmas card list, raising several thousand dollars. In the summer of 1949, Schmoe and three other Americans sailed to Japan with building materials and food and medical supplies for the Hiroshima hospital. With the assistance of many Japanese volunteers, and some skilled craftsmen whom they paid, the group built two duplexes to house four homeless families. Hiroshima Mayor Hamai and other city officials actively supported the project, and the four homes were turned over to the city housing authority, which selected the occupants from the 3,800 families who applied.

For the next four summers, Schmoe returned to Japan to build homes for families who had lost theirs in the bombings. Working largely with local volunteers, the project constructed a total of about 20 houses in Hiroshima and another 12 in Nagasaki. Many of the buildings were multi-unit and several were community houses, so altogether Houses for Hiroshima helped to house close to 100 families.

Korea and Sinai

While Schmoe was helping to rebuild Japan, the Korean War was devastating that country. After the Korean Armistice ended the fighting in 1953, the United Nations Korean Relief Agency invited Schmoe to help war refugees there. He set up Houses for Korea, funded by the U.N. and private donations, and selected the Yongin Valley, where fighting in 1950 had destroyed 75 percent of the homes, as the area that the project would assist. From 1953 through 1956, Houses for Korea built homes, dug wells, repaired roads and irrigation systems, and set up a free clinic to provide medical care.

In 1956, Schmoe's attention was drawn to the victims of yet another conflict. When Britain and France bombed Egypt in 1956 following the nationalization of the Suez Canal, 4,000 families in Port Said were displaced. Egyptian President Gamel Nasser planned to resettle them in the Sinai Desert (in part to assert Egyptian control over the area, which Israel had invaded during the fighting). At the urging of Gordon and Esther Hirabayashi, who were working at American University in Cairo, Schmoe formed Wells for Egypt in 1957 to help develop the oasis of El Arish where some of the refugees were settled. He raised money to purchase a pump for the oasis well and nursery plants to start an orchard, and spent several weeks helping plant the orchard.

Writing and Travel

After working in the Sinai, Schmoe flew to Nairobi and traveled by boat back down the Nile to Cairo where Esther and her family were living. The Sinai project marked the end of 17 years of full time, though rarely fully paid, aid work. Schmoe "retired" in 1958 to devote himself to writing. He had already followed Our Greatest Mountain with several more books, including Japan Journey in 1950, describing his 1949 house-building trip. A Year in Paradise, one of his most enduring works, appeared in 1959. It recounts the time Floyd and Ruth spent at Paradise on Mount Rainier in 1920 and their trip around the mountain's Wonderland Trail a few years later when son Ken was a toddler.

Schmoe turned to another of his favorite places in For Love of Some Islands, published in 1964. It centers on a family reunion in 1961 when Floyd, Ruth, and their four children, now accompanied by four spouses and 12 children of their own, returned to their beloved San Juan Islands, interspersing Schmoe's descriptions of and ruminations on the islands' natural history with family adventures, beginning with his construction of a glass-bottomed houseboat from which he and his grandchildren could observe underwater life.

Ruth Schmoe, who had had heart trouble for some years, died in 1969. Despite the loss of the person he called "the greatest thing that ever happened to me" (Lewis, 60), Floyd kept up an active and productive life. Later in 1969, he and his son Ken traveled in Asia. The following year he traveled again, surprising friends when he returned home remarried. He and Tomiko Yamizaki, who had worked for AFSC in Tokyo and years earlier was one of the first Houses for Hiroshima volunteers, met and married in Paris, then traveled through Europe and Africa.

Schmoe continued to travel, write, and undertake new projects well into his 90s. As he did so, his age and accomplishments brought him a degree of celebrity. Responding to a frequently asked question about his longevity, he told one interviewer:

"First, be very careful in the choice of your ancestors. That's one reason I reached 90. And always have something important to do tomorrow" (Angelos).

Peace Parks

In 1987, assisted by other members of Seattle's University Friends Meeting, Schmoe began clearing brambles and trash from a vacant lot near University Bridge across the street from the meeting house to create the Seattle Peace Park. The following summer he traveled with other volunteers from King County to Tashkent (one of Seattle's many sister cities, then part of the Soviet Union, later the capital of Uzbekistan) and at age 92 poured concrete in 100-plus degree heat to help build a peace park there. Later in 1988 Schmoe went to Japan, where he became the second recipient of the Hiroshima Peace Center's Peace Award.

Schmoe used the money from his Peace Award to help fund completion of the Seattle Peace Park, which was dedicated on August 6, 1990, the 45th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing. The small park contains a bronze statue of Sadako Sasaki (1943-1955) of Hiroshima, who died at age 12 of leukemia caused by the bomb, holding a paper crane. Before her death Sadako folded origami paper cranes, attempting to reach 1,000, which according to legend would grant her health. People have been folding cranes ever since as a sign of peace and the statue is often draped with them.

Schmoe's energy and health declined after his son Ken died in a freak accident in December 1996 when a snow-covered tree fell on him. But until the end of his life Schmoe retained his curiosity about the natural and human world and had "something important to do tomorrow" -- usually a long list. Even with all he had accomplished he felt he should do more, telling an interviewer a year before he died:

"Each day I pray ... and I beg forgiveness for my neglect of all those who I could not help" (Barber, "One of History's Voices…").

Floyd Schmoe was 105 when he died in Kenmore on April 20, 2001, leaving 54 living descendants (three surviving children, 15 grandchildren, 34 great-grandchildren, and two great-great-grandchildren) and a legacy of helping others that spanned four continents and more than eighty years.This essay made possible by:

4Culture King County Lodging Tax

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001), building a house in Hiroshima, Japan, October 4, 1952

Courtesy Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Floyd Schmoe on Hiroshima, interviewed by Elmer Good, Seattle, 1998

Courtesy Densho Digital Archive

Floyd Schmoe on mortality, interviewed by Elmer Good, Seattle, 1998

Courtesy Densho Digital Archive

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001), Mount Rainier National Park naturalist, demonstrates "Nature Coasting," 1920s

Courtesy Mount Rainier National Park Archives

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001), first full-time naturalist at Mount Rainier National Park, 1920s

Courtesy Mount Rainier National Park Archives

Paradise, Mount Rainier National Park, July 23, 2005

Photo by Colleen E. O'Connor

Flower Island with Spencer Spit and Lopez Island in background, June 2, 2003

HistoryLink.org Photo by Kit Oldham

Ruins of waiting room entrance station at Minidoka Relocation Center, Minidoka National Monument, Hunt, Idaho, 2004

Photo by Paula Becker

Floyd Schmoe (1895-2001)

Courtesy World Peace Project for Children

Sadako Sasaki Peace Child (Daryl Smith, 1990), Seattle Peace Park, February 28, 2010

HistoryLink.org Photo by Kit Oldham

Sources:

Floyd Schmoe, A Year In Paradise (Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1999); Schmoe, For Love of Some Islands (New York: Harper & Row, 1964); Schmoe, "Seattle's Peace Churches and Relocation" in Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress ed. by Roger Daniels et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, [1986], 1991), 117-22; Schmoe, "Construction of an Under-Seas Observation Post and a Method of Under-Water Photography" (master's thesis, University of Washington, 1937); Floyd Wilfred Schmoe Papers, Box 1, Folders 1-3, 33; Box 2, Folders 4-7; Box 8, Folders 23, 25; Box 12, Folders 1, 25-28; Box 13, Folders 9, 14, 17, Accession No. 496-8, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle; "Oral History Interview No. 21," American Friends Service Committee, transcript of Kitty Barragato interview of Floyd Schmoe on February 25, 1989, copy in possession of American Friends Service Committee, Philadelphia; "Floyd Schmoe Interview I & II," Densho Digital Archive, transcripts of Elmer Good interviews of Floyd Schmoe on June 10 and June 22, 1998, copies in possession of Densho Digital Archive, Seattle (www.densho.org); Rose Lewis, "Floyd and Ruth Schmoe: Idealism, Service, Adventure and Commitment in Two Quaker Lives" unpublished typescript dated May 1998, copies in possession of Rose Lewis, Salem, Oregon, and of University Friends Meeting, Seattle; Lewis, notes of interviews with Bill and Lillian Schmoe (July 21-22, 1998) and Inez Schmoe Voorhees (May 19, 1998), copies in possession of Rose Lewis, Salem, OR, and of University Friends Meeting, Seattle; Lynn Thompson, "Vet's Dream: Military Museum," The Seattle Times, June 30, 2004 (http://archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com/web/); Ray Rivera, "Floyd Schmoe's Lifetime of the Heart Remembered," Ibid., April 30, 2001; Marc Ramirez, "A Prime Activist: Creator of Seattle Peace Park is Dead at 105," Ibid., April 24, 2001; Paula Bock, "Floyd Schmoe -- 101 Years Of Peace And Action," Ibid., September 14, 1997; Alex Tizon, "Sharing Hope for Peace," Ibid., March 30, 1997; Constantine Angelos, "At 94, He's Busy Building A Peace Park -- Many Join His Effort," Ibid., July 12, 1990; Mike Barber, "In the Midst of Wars, He Sought Peace and Justice," Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 27, 2001 (http://www.seattlepi.com); Barber, "One of History's Voices for Peace and Justice," Ibid., January 1, 2000; Vanessa Ho, "He Lived in Peace, He Rests in Peace after Tree Falls," Ibid., December 31, 1996; Judi Hunt, "Floyd Schmoe Isn't Ready to Rest until There Is Peace," Ibid., March 18, 1995; Paul Swortz, "Park Emerges from Dump Site: Volunteers Plan Peace Tribute," Ibid., July 24, 1987; Bob McIntyre, Jr., "Floyd W. Schmoe," Mount Rainier National Park Nature Notes website accessed January 22, 2010 (www.nps.gov/archive/mora/notes/schmoe.htm); "Houses for Hiroshima," Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum website accessed January 22, 2010 (www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/exhibit_e/exh0708_e/exh070807_e.html); "About AFSC," American Friends Service Committee website accessed February 18, 2010 (http://www.afsc.org/ht/d/sp/i/267/pid/267); HistoryLink.org, The Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, "Hirabayashi, Gordon K. (b. 1918)" (by David Takami) and "Seattle Tashkent Peace Park in Uzbekistan is dedicated in Tashkent and at Seattle Center on September 12, 1988" (by Priscilla Long) http://www.historylink.org (accessed February 17, 2010).

Note: This essay was revised and substantially expanded on February 25, 2010.