화엄철학 : 쉽게 풀어쓴 불교철학의 정수[양장]

저 : 까르마 C.C. 츠앙, 이찬수

출판사 : 경서원발행 : 1990년 08월 20일

쪽수 : 428

[중고] 화엄철학 중 9,000원

-----

목차

머리말

일러두기

들어가는 말

제1부 총체성의 세계

부처의 무한한 경계

총체성에 관한 대화

무애-총체성의 추축

거울로 둘러싸인 방

총체성의 근본원인

보살이 깨달음에 이르기 위한 열 단계

부사의한 불법

삼매, 신통력, 법계

제2부 화엄의 철학적 기초

머리글

제1장 공의 철학

공-불교의 핵심

반야심경의 요지

무아설과 자성공

절대공

쑤냐타와 논리학

쑤냐타의 의의

제2장 총체성의 철학

상즉과 상입-화엄철학의 두 기본 원리

상즉에 대한 검토

사법계 철학

제3장 유심론

마음과 외부의 세계

알라야식과 총체성

제3부 화엄 문헌 몇편과 조사들의 전기

[보현행원품]

[반야심경약소]

[법계관문]

[금사자장]

조사들의 전기

맺음말

옮긴이의 말

낱말풀이

찾아보기

펼쳐보기

--------------------------

저자소개

까르마 C.C. 츠앙 [저]

펜실바니아 주립대학 종교학과 불교전공 교수.

저서로 [선수행],[티벳 요가의 가르침] 등이 있다.

-------------------------------

이찬수 [저]

서강대학교 화학과를 졸업하고 같은 대학교 대학원 종교학과에서 불교학과 신학으로 각각 석사학위를, 칼 라너(Karl Rahner)와 니시타니 게이지(西谷啓治)를 비교하여 박사학위를 받았다. 강남대학교 교수, (일본)WCRP평화연구소 객원연구원, 대화문화아카데미 연구위원 등을 지냈고, 종교철학에 기반한 평화인문학의 심화와 확장을 연구 과제로 삼고 있다. 저서로 [평화와 평화들: 평화다원주의와 평화인문학], [다르지만 조화한다, 불교와 기독교의 내통], [사람이 사람을 심판할 수 있는가: 사형폐지론과 회복적 정의](공역), [아시아평화공동체]가 있고, 논문으로는펼쳐보기

저자의 다른책

--------------------------------------------

이 책의 기대평(한줄평)을 간단히 남겨주세요.

등록하기

기대평10.0최근순평점 높은순

kang***

화엄철학의 진수!!

2016/09/07

eunis***

저술이 탁월하여, 화엄경을 읽기 전에, 그리고 읽은 후에 각각 읽어본다면 가슴에 와닿을 것입니다!

2011/04/07

==============

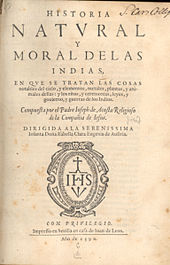

The Buddhist Teaching of Totality: The Philosophy of Hwa Yen Buddhism, 1971

by Garma C.C. Chang (Author)

4.3 out of 5 stars 9 ratings

---

The Hwa Yen school of Mahayana Buddhism bloomed in China in the 7th and 8th centuries A.D. Today many scholars regard its doctrines of Emptiness, Totality, and Mind-Only as the crown of Buddhist thought and as a useful and unique philosophical system and explanation of man, world, and life as intuitively experienced in Zen practice. For the first time in any Western language Garma Chang explains and exemplifies these doctrines with references to both oriental masters and Western philosophers. The Buddha's mystical experience of infinity and totality provides the framework for this objective revelation of the three pervasive and interlocking concepts upon which any study of Mahayana philosophy must depend. Following an introductory section describing the essential differences between Judeo-Christian and Buddhist philosophy, Professor Chang provides an extensive, expertly developed section on the philosophical foundations of Hwa Yen Buddhism dealing with the core concept of True Voidness, the philosophy of Totality, and the doctrine of Mind-Only. A concluding section includes selections of Hwa Yen readings and biographies of the patriarchs, as well as a glossary and list of Chinese terms.

300 pages

--------------------

4.7 out of 5 stars 11

Paperback

$24.00

---

Editorial Reviews

Review

“That The Buddhist Teaching of Totality is a unique and long-needed contribution to Buddhological literature in English cannot be denied. Not only is it one of the very few introductions to a school of Chinese Buddhism other than Ch’an, it is one of the few attempts in any language to present systematically the essential features of the Flower (Hwa Yen) Garland School, perhaps the most philosophical sophisticated example of Buddhist syncretism ever to be produced.”

—Journal of the American Oriental Society

“Chang’s style is easy and concise, enjoyable, and stimulating. . . . This would be a useful book for any college or university library. Highly recommended.”

—Choice

“[This] is indeed a most welcome addition to the literature on the most comprehensive and most profound branch of Chinese Buddhism, the Hwa Yen School. . . . [It is] a work of real and present value.”

—Main Currents in Modern Thought

“The Western student of Buddhism should be grateful for this first full-length treatment in English of an important and interesting school of Buddhist thought.”

—Philosophy East and West

“This book is highly recommended to advanced students of Buddhism and to Westerners whose interests in Buddhism incline toward the metaphysical and phenomenological.”

—Philosophy and Phenomenological Research

About the Author

Renowned for his English translation of The 100,000 Songs of Milarepa, Garma Chen-Chi Chang was also the author of The Practice of Zen and The Teachings of Tibetan Yoga, and the editor and translator of A Treasury of Mahāyāna Sūtras. At the time of his death in 1988, Dr. Chang was Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at The Pennsylvania State University.

Product details

Publisher : Pennsylvania State University Press; 1st edition (September 1, 1971)

Language : English

Paperback : 300 pages

-----------------------

Customer Reviews: 4.3 out of 5 stars 9 ratings

--------------

Top reviews from the United States

Tay Yong Meng

3.0 out of 5 stars The book is well written with very good and clear explanations and examples/parables to enhance the meanings

Reviewed in the United States on January 5, 2017

Verified Purchase

The book is well written with very good and clear explanations and examples/parables to enhance the meanings. However, the ereader version has many typo errors.

One person found this helpful

---------------------

richard hunn

5.0 out of 5 stars An authoritative study by an experienced Buddhist

Reviewed in the United States on April 3, 2002

For an easy ride, visit Disneyland. C.C. Chang's study of the Hua Yen is a demanding work, because it presuposes that the reader wishes to find such insight - through practice. The Hua Yen Ching is said to have been expounded immediately after the Buddha's own enlightenment. It is one of the few sutras that actually endeavour to hint about the enlightened state itself- positively, rather than obliquely, by referring to it in relation to what it is not (viz. asrava, klesa defilements, trsna, dualism) - the 'neither-nor' aspect. Hua Yen deals with the 'mutually inclusive' dimension(s) of totality. Beware! Too many Western writings on Hua Yen (Kegon) jump straight into shih-shih wu ai - the 'non-obstruction between thing-events.' But actually, without insight into li-shih wu ai, seeing 'form' as grounded in the kung or 'void' aspect, nobody knows anything about shih-shih wu ai. C.C. Chang had the best Chinese and Tibetan teachers. He writes with authority - because he writes with eperiential insight into what the Hua Yen teaches. I've savoured Chang's work for 25 years, yet it remnains as inspiring and stimulating, as the day I first saw it. A lifelong study this. Find the meaning in your own experience. Candy is for the kids!

31 people found this helpful

-----------------

Barnaby A Thieme

3.0 out of 5 stars Good Intro, though sectarian

Reviewed in the United States on May 29, 2002

The Hwa Yen school, which drew chiefly from the Avatamsaka Sutra (translated by Cleary), emphasizes Dharma from the perspective of realization, or enlightened mind. Like the Lotus Sutra, The Avatamsaka Sutra is equally an evocation of a state of mind as a presentation of information. The Hwa Yen thinkers of Sung China used this as their starting point to paint a dazzling portrait of our universe filled with mind-blowing images and rich ideas.

This is a pretty good introduction to Hwa Yen Buddhism, although the reader will have to wade through a fair amount of unapologetic sectarianism. Hwa Yen, we learn, is the "highest" and "most advanced" form of Buddhism, and Chang clearly considers himself to have full knowledge of what Buddha "really meant" in his teachings. Despite this sometimes tedious lack of modesty, the book is a good overview of the history and doctrine of this school. Given the unfortunate paucity of material on this intriguing movement, that is a welcome addition.

19 people found this helpful

--------------

accwai

5.0 out of 5 stars Don't skip this one...

Reviewed in the United States on August 1, 2002

The first reviewer says skip this and go to Thomas Cleary. I would assume that means "Entry into the Inconceivable". I have both actually, and I like "The Buddhist Teaching of Totality" better.

To me, the Cleary approach seems to be just to pick you up and dump you right into the middle of things. By page 24, you're already into the four dharmadatu's. These are very subtle concepts that require serious preparation to understand deeply. They may be interesting doctrines if you're into that kind of thing, but I personally like to see how all the pieces fit together. In that sense, I'm totally lost. The Garma Chang book covers a lot more basics before going into the heavy stuff. The pace may be slower, but in the end, I have a much clearer picture. And after that, the Cleary book becomes much more palatable.

Another reviewer mentioned that Garma Chang seems to think he knows everything. I don't know, but from the writing, it's clear that he has a great deal of personal experience on the subject at hand. His discussion on emptyness, for example, is particularly subtle and insightful. Thomas Cleary, on the other hand, doesn't seem to show much opinion of his own. Much of the "Entry into the Inconceivable" text is translated from Chinese works. Same goes for his translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra itself as well. Even the introduction is paraphrasing of Chinese text. Not that translation is not useful of course...

A bonus included in the Garma Chang book is an almost complete translation of "The Great Vows of Samantabhadra". It is important because it's supposed to give one a good feel for what the complete Avatamsaka is like. It is the last part of the Forty Hwa Yen and is often treated as a separate sutra on its own. (It's also classified as one of the Five Sutras of Pure Land) And it's not in Cleary's English translation of Avatamsaka Sutra, which is strictly a translation of Eighty Hwa Yen.

In any case, I'd probably get both books. They serve different purposes. Seems to me that the person who says to skip this one is treating the meaning of the books as self-existent and real and therefore their relative merit should be completely self-evident. We all know that is not true right?

Read less

43 people found this helpful

---

Frank J. Boccio

5.0 out of 5 stars A justifiably classic "Classic."

Reviewed in the United States on March 24, 2007

Chang has done something really important and necessary in writing this concise and comprehensible overview of Hwa-Yen philosophy. I'd recommend this to any student who wishes to cultivate a deeper understanding of the Avatamsaka Sutra and the elements of Mahayana thought that culminates in Hwa-Yen.

3 people found this helpful

------------

Write a review

Peter Kalnin

Apr 13, 2020Peter Kalnin rated it it was amazing

This was another writer whom Professor Francis Cook introduced to a very small class of students at the University of California, Riverside in 1971. I felt honored and privileged to have been a part of that group and very lucky to have Professor Cook as a guide to an esoteric but beautiful part of the Buddhist cannon.

----

Thank you Professor Cook.

flagLike · comment · see review

Greg

Mar 30, 2009Greg rated it really liked it

Shelves: buddhism

This is an excellent introduction to the doctrines of Hwa Yen Buddhism. The author does a good job of distinguishing that school from other schools of Chinese and Japanese Buddhism. One thing that the author stresses is that although there is a large doctrinal literature, really what the doctrine is meant to do is not build philosophical systems, but rather to explain the experiences that practitioners have while meditating - i.e., enlightenment.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to

Wikimedia Commons has media related to