Russian literature

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Literature |

| Sport |

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia and its émigrés and to Russian-language literature. The roots of Russian literature can be traced to the Middle Ages, when epics and chronicles in Old East Slavic were composed. By the Age of Enlightenment, literature had grown in importance, and from the early 1830s, Russian literature underwent an astounding golden age in poetry, prose and drama. Romanticism permitted a flowering of poetic talent: Vasily Zhukovsky and later his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore. Prose was flourishing as well. The first great Russian novelist was Nikolai Gogol. Then came Ivan Turgenev, who mastered both short stories and novels. Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy soon became internationally renowned. In the second half of the century Anton Chekhov excelled in short stories and became a leading dramatist. The beginning of the 20th century ranks as the Silver Age of Russian poetry. The poets most often associated with the "Silver Age" are Konstantin Balmont, Valery Bryusov, Alexander Blok, Anna Akhmatova, Nikolay Gumilyov, Osip Mandelstam, Sergei Yesenin, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Marina Tsvetaeva and Boris Pasternak. This era produced some first-rate novelists and short-story writers, such as Aleksandr Kuprin, Nobel Prize winner Ivan Bunin, Leonid Andreyev, Fyodor Sologub, Aleksey Remizov, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Andrei Bely and Maxim Gorky.

After the Revolution of 1917, Russian literature split into Soviet and white émigré parts. While the Soviet Union assured universal literacy and a highly developed book printing industry, it also enforced ideological censorship. In the 1930s Socialist realism became the predominant trend in Russia. Its leading figures were Nikolay Ostrovsky, Mikhail Sholokhov, Alexander Fadeyev and other writers, who laid the foundations of this style. Ostrovsky's novel How the Steel Was Tempered has been among the most successful works of Russian literature. Alexander Fadeyev achieved success in Russia. Various émigré writers, such as poets Vladislav Khodasevich, Georgy Ivanov and Vyacheslav Ivanov; novelists such as Mark Aldanov, Gaito Gazdanov and Vladimir Nabokov; and short story Nobel Prize-winning writer Ivan Bunin, continued to write in exile. Some writers dared to oppose Soviet ideology, like Nobel Prize-winning novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who wrote about life in the gulag camps. The Khrushchev Thaw brought some fresh wind to literature and poetry became a mass cultural phenomenon. This "thaw" did not last long; in the 1970s, some of the most prominent authors were banned from publishing and prosecuted for their anti-Soviet sentiments.

Other notable Soviet writers are Mikhail Bulgakov and Andrei Platonov.

The end of the 20th century was a difficult period for Russian literature, with few distinct voices. Among the most discussed authors of this period were Victor Pelevin, who gained popularity with short stories and novels, novelist and playwright Vladimir Sorokin, and the poet Dmitri Prigov. In the 21st century, a new generation of Russian authors appeared, differing greatly from the postmodernist Russian prose of the late 20th century, which lead critics to speak about "new realism".

Russian authors have significantly contributed to numerous literary genres. Russia has five Nobel Prize in literature laureates. As of 2011, Russia was the fourth largest book producer in the world in terms of published titles.[1] A popular folk saying claims Russians are "the world's most reading nation".[2][3]

Early history[edit source]

Old Russian literature consists of several masterpieces written in the Old East Slavic (i.e. the language of Kievan Rus', not to be confused with the contemporaneous Church Slavonic nor with modern Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian). The main type of Old Russian historical literature were chronicles, most of them anonymous.[4] Anonymous works also include The Tale of Igor's Campaign and Praying of Daniel the Immured. Hagiographies (Russian: жития святых, zhitiya svyatykh, "lives of the saints") formed a popular genre of the Old Russian literature. Life of Alexander Nevsky offers a well-known example. Other Russian literary monuments include Zadonschina, Physiologist, Synopsis and A Journey Beyond the Three Seas. Bylinas – oral folk epics – fused Christian and pagan traditions. Medieval Russian literature had an overwhelmingly religious character and used an adapted form of the Church Slavonic language with many South Slavic elements. The first work in colloquial Russian, the autobiography of the archpriest Avvakum, emerged only in the mid-17th century.

18th century[edit source]

After taking the throne at the end of the 17th century, Peter the Great's influence on the Russian culture would extend far into the 18th century. Peter's reign during the beginning of the 18th century initiated a series of modernizing changes in Russian literature. The reforms he implemented encouraged Russian artists and scientists to make innovations in their crafts and fields with the intention of creating an economy and culture comparable. Peter's example set a precedent for the remainder of the 18th century as Russian writers began to form clear ideas about the proper use and progression of the Russian language. Through their debates regarding versification of the Russian language and tone of Russian literature, the writers in the first half of the 18th century were able to lay foundation for the more poignant, topical work of the late 18th century.

Satirist Antiokh Dmitrievich Kantemir, 1708–1744, was one of the earliest Russian writers not only to praise the ideals of Peter I's reforms but the ideals of the growing Enlightenment movement in Europe. Kantemir's works regularly expressed his admiration for Peter, most notably in his epic dedicated to the emperor entitled Petrida. More often, however, Kantemir indirectly praised Peter's influence through his satiric criticism of Russia's “superficiality and obscurantism,” which he saw as manifestations of the backwardness Peter attempted to correct through his reforms.[5] Kantemir honored this tradition of reform not only through his support for Peter, but by initiating a decade-long debate on the proper syllabic versification using the Russian language.

Vasily Kirillovich Trediakovsky, a poet, playwright, essayist, translator and contemporary to Antiokh Kantemir, also found himself deeply entrenched in Enlightenment conventions in his work with the Russian Academy of Sciences and his groundbreaking translations of French and classical works to the Russian language. A turning point in the course of Russian literature, his translation of Paul Tallemant's work Voyage to the Isle of Love, was the first to use the Russian vernacular as opposed the formal and outdated Church-Slavonic.[6] This introduction set a precedent for secular works to be composed in the vernacular, while sacred texts would remain in Church-Slavonic. However, his work was often incredibly theoretical and scholarly, focused on promoting the versification of the language with which he spoke.

While Trediakovsky's approach to writing is often described as highly erudite, the young writer and scholarly rival to Trediakovsky, Alexander Petrovich Sumarokov, 1717–1777, was dedicated to the styles of French classicism. Sumarokov's interest in the form of French literature mirrored his devotion to the westernizing spirit of Peter the Great's age. Although he often disagreed with Trediakovsky, Sumarokov also advocated the use of simple, natural language in order to diversify the audience and make more efficient use of the Russian language. Like his colleagues and counterparts, Sumarokov extolled the legacy of Peter I, writing in his manifesto Epistle on Poetry, “The great Peter hurls his thunder from the Baltic shores, the Russian sword glitters in all corners of the universe”.[7] Peter the Great's policies of westernization and displays of military prowess naturally attracted Sumarokov and his contemporaries.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov, in particular, expressed his gratitude for and dedication to Peter's legacy in his unfinished Peter the Great, Lomonosov's works often focused on themes of the awe-inspiring, grandeur nature, and was therefore drawn to Peter because of the magnitude of his military, architectural and cultural feats. In contrast to Sumarokov's devotion to simplicity, Lomonosov favored a belief in a hierarchy of literary styles divided into high, middle and low. This style facilitated Lomonosov's grandiose, high minded writing and use of both vernacular and Church-Slavonic.[8]

The influence of Peter I and debates over the function and form of literature as it related to the Russian language in the first half of the 18th century set a stylistic precedent for the writers during the reign of Catherine the Great in the second half of the century. However, the themes and scopes of the works these writers produced were often more poignant, political and controversial. Alexander Nikolayevich Radishchev, for example, shocked the Russian public with his depictions of the socio-economic condition of the serfs. Empress Catherine II condemned this portrayal, forcing Radishchev into exile in Siberia.[9]

Others, however, picked topics less offensive to the autocrat. Nikolay Karamzin, 1766–1826, for example, is known for his advocacy of Russian writers adopting traits in the poetry and prose like a heightened sense of emotion and physical vanity, considered to be feminine at the time as well as supporting the cause of female Russian writers. Karamzin's call for male writers to write with femininity was not in accordance with the Enlightenment ideals of reason and theory, considered masculine attributes. His works were thus not universally well received; however, they did reflect in some areas of society a growing respect for, or at least ambivalence toward, a female ruler in Catherine the Great. This concept heralded an era of regarding female characteristics in writing as an abstract concept linked with attributes of frivolity, vanity and pathos.

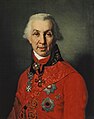

Some writers, on the other hand, were more direct in their praise for Catherine II. Gavrila Romanovich Derzhavin, famous for his odes, often dedicated his poems to Empress Catherine II. In contrast to most of his contemporaries, Derzhavin was highly devoted to his state; he served in the military, before rising to various roles in Catherine II's government, including secretary to the Empress and Minister of Justice. Unlike those who took after the grand style of Mikhail Lomonosov and Alexander Sumarokov, Derzhavin was concerned with the minute details of his subjects.

Denis Fonvizin, an author primarily of comedy, approached the subject of the Russian nobility with an angle of critique. Fonvizin felt the nobility should be held to the standards they were under the reign of Peter the Great, during which the quality of devotion to the state was rewarded. His works criticized the current system for rewarding the nobility without holding them responsible for the duties they once performed. Using satire and comedy, Fonvizin supported a system of nobility in which the elite were rewarded based upon personal merit rather than the hierarchal favoritism that was rampant during Catherine the Great's reign.[10]

Golden Age[edit source]

The 19th century is traditionally referred to as the "Golden Era" of Russian literature. Romanticism permitted a flowering of especially poetic talent: the names of Vasily Zhukovsky and later that of his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore. Pushkin is credited with both crystallizing the literary Russian language and introducing a new level of artistry to Russian literature. His best-known work is a novel in verse, Eugene Onegin. An entire new generation of poets including Mikhail Lermontov, Yevgeny Baratynsky, Konstantin Batyushkov, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, Fyodor Tyutchev and Afanasy Fet followed in Pushkin's steps.

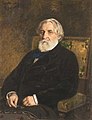

Prose was flourishing as well. The first great Russian novel was Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol. The realistic school of fiction can be said to have begun with Ivan Turgenev. Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Leo Tolstoy soon became internationally renowned to the point that many scholars such as F. R. Leavis have described one or the other as the greatest novelist ever. Ivan Goncharov is remembered mainly for his novel Oblomov. Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin is known for his novel The Golovlyov Family, while Nikolai Leskov is best remembered for his shorter fiction. Late in the century Anton Chekhov emerged as a master of the short story as well as a leading international dramatist.

Other important 19th-century developments included the fabulist Ivan Krylov; non-fiction writers such as the critic Vissarion Belinsky and the political reformer Alexander Herzen; playwrights such as Aleksandr Griboyedov, Aleksandr Ostrovsky and the satirist Kozma Prutkov (a collective pen name).

Silver Age[edit source]

The beginning of the 20th century ranks as the Silver Age of Russian poetry. Well-known poets of the period include: Alexander Blok, Sergei Yesenin, Valery Bryusov, Konstantin Balmont, Mikhail Kuzmin, Igor Severyanin, Sasha Chorny, Nikolay Gumilyov, Maximilian Voloshin, Innokenty Annensky, Zinaida Gippius. The poets most often associated with the "Silver Age" are Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam and Boris Pasternak.

While the Silver Age is considered to be the development of the 19th-century Russian literature tradition, some avant-garde poets tried to overturn it: Velimir Khlebnikov, David Burliuk, Aleksei Kruchenykh and Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Though the Silver Age is famous mostly for its poetry, it produced some first-rate novelists and short-story writers, such as Aleksandr Kuprin, Nobel Prize winner Ivan Bunin, Leonid Andreyev, Fedor Sologub, Aleksey Remizov, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Andrei Bely, though most of them wrote poetry as well as prose.

20th century[edit source]

Lenin era[edit source]

The first years of the Soviet regime after the October Revolution of 1917, featured a proliferation of avant-garde literature groups. One of the most important was the Oberiu movement (1928–1930s), which included the most famous Russian absurdist Daniil Kharms (1905–1942), Konstantin Vaginov (1899–1934), Alexander Vvedensky (1904–1941) and Nikolay Zabolotsky (1903–1958). Other famous authors experimenting with language included the novelists Yuri Olesha (1899–1960) and Andrei Platonov (1899–1951) and the short-story writers Isaak Babel (1894–1940) and Mikhail Zoshchenko (1894–1958). The OPOJAZ group of literary critics, also known as Russian formalism, was founded in 1916 in close connection with Russian Futurism. Two of its members also produced influential literary works, namely Viktor Shklovsky (1893–1984), whose numerous books (e.g., Zoo, or Letters Not About Love, 1923) defy genre in that they present a novel mix of narration, autobiography, and aesthetic as well as social commentary, and Yury Tynyanov (1893–1943), who used his knowledge of Russia's literary history to produce a set of historical novels mainly set in the Pushkin era (e.g., Young Pushkin: A Novel).

Following the establishment of Bolshevik rule, Mayakovsky worked on interpreting the facts of the new reality. His works, such as "Ode to the Revolution" and "Left March" (both 1918), brought innovations to poetry. In "Left March", Mayakovsky calls for a struggle against the enemies of the Russian Revolution. The poem "150,000,000" discusses the leading role played by the masses in the revolution. In the poem "Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1924), Mayakovsky looks at the life and work at the leader of Russia's revolution and depicts them against a broad historical background. In the poem "It's Good", Mayakovsky writes about socialist society as the "springtime of humanity". Mayakovsky was instrumental in producing a new type of poetry in which politics played a major part.[11]

Socialist Realism[edit source]

In the 1930s, Socialist Realism became the predominant trend in Russia. Writers like those of the Serapion Brothers group (1921–), who insisted on the right of an author to write independently of political ideology, were forced by authorities to reject their views and accept socialist realist principles. Some 1930s writers, such as Osip Mandelstam, Daniil Kharms, leader of Oberiu, Mikhail Bulgakov (1891–1940), author of The White Guard (1923) and The Master and Margarita (1928–1940), and Andrei Platonov, author of novels Chevengur (1928) and The Foundation Pit (1930) wrote with little or no hope of being published.

After his return to Russia Maxim Gorky was proclaimed by the Soviet authorities as "the founder of Socialist Realism". His novel Mother (1906), which Gorky himself considered one of his biggest failures, inspired proletarian writers to found the socrealist movement. Gorky defined socialist realism as the "realism of people who are rebuilding the world" and pointed out that it looks at the past "from the heights of the future's goals", although he defined it not as a strict style (which is studied in Andrei Sinyavsky's essay On Socialist Realism), but as a label for the "union of writers of styles", who write for one purpose, to help in the development of the new man in socialist society. Gorky became the initiator of creating the Writer's Union, a state organization, intented to unite the socrealist writers. Gorky's works became significant for the development of literature in Russia and influential in many parts of the world.[12] Despite the official reputation, Gorky's post-revolutionary works, such as the novel The Life of Klim Samgin (1925–1936) can't be defined as socrealist.

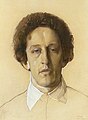

Andrei Bely (1880–1934), author of Petersburg (1913/1922), a well-known modernist writer, also was a member of Writer's Union and tried to become a "true" socrealist by writing a series of articles and making ideological revisions to his memoirs, and he also planned to begin a study of Socialist Realism. However, he continued writing with his unique techniques.[13] Although he was actively published during his lifetime, his major works would not be published until the end of 1970s.

Nikolay Ostrovsky's novel How the Steel Was Tempered (1932–1934) has been among the most successful works of Russian literature,[citation needed] with tens of millions of copies printed in many languages around the world. In China, various versions of the book have sold more than 10 million copies.[14] In Russia more than 35 million copies of the book are in circulation.[15] The book is a fictionalized autobiography of Ostrovsky's life: he had a difficult working-class childhood, became a Komsomol member in July 1919 and volunteered to join the Red Army. The novel's protagonist, Pavel Korchagin, represented the "young hero" of Russian literature: he is dedicated to his political causes, which help him to overcome his tragedies. The novel has served as an inspiration to youths around the world and played a mobilizing role in Russia's Great Patriotic War.[16][need quotation to verify]

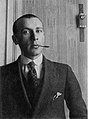

Alexander Fadeyev (1901–1956) achieved noteworthy success in Russia, with tens of millions of copies of his books in circulation in Russia and around the world.[15] Many of Fadeyev's works have been staged and filmed and translated into many languages of Russia and around the world. Fadeyev served as a secretary of the Soviet Writers' Union and as the general secretary of the union's administrative board from 1946 to 1954. The Soviet Union awarded him two Orders of Lenin and various medals. His novel The Rout (1927) deals with the partisan struggle in Russia's Far East during the Russian Revolution and Civil War of 1917–1922. Fadeyev described the theme of this novel as one of a revolution significantly transforming the masses. The novel's protagonist, Levinson is a Bolshevik revolutionary who has a high level of political consciousness. The novel The Young Guard (1946), which received the State Prize of the USSR in 1946, focuses on an underground Komsomol group in Krasnodon, Ukraine and their struggle against the fascist occupation.[17]

Émigré writers[edit source]

Meanwhile, émigré writers, such as poets Vladislav Khodasevich (1886–1939), Georgy Ivanov (1894–1958) and Vyacheslav Ivanov (1866–1949); novelists such as Mark Aldanov (1880s–1957), Gaito Gazdanov (1903–1971) and Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977); and short-story Nobel Prize-winning writer Ivan Bunin (1870–1953), continued to write in exile.

Later Soviet era[edit source]

After the end of World War II Nobel Prize-winning Boris Pasternak (1890–1960) wrote a novel Doctor Zhivago (1945–1955). Publication of the novel in Italy caused a scandal, as the Soviet authorities forced Pasternak to renounce his 1958 Nobel Prize and denounced as an internal White emigre and a Fascist fifth columnist. Pasternak was expelled from the Writer's Union.

The Khrushchev Thaw (c. 1954 – c. 1964) brought some fresh wind to literature. Poetry became a mass-cultural phenomenon: Bella Akhmadulina (1937–2010), Robert Rozhdestvensky (1932–1994), Andrei Voznesensky (1933–2010), and Yevgeny Yevtushenko (1933–2017), read their poems in stadiums and attracted huge crowds.

Some writers dared to oppose Soviet ideology, like short-story writer Varlam Shalamov (1907–1982) and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008), who wrote about life in the gulag camps, or Vasily Grossman (1905–1964), with his description of World War II events countering the Soviet official historiography (his epic novel Life and Fate (1959) was not published in the Soviet Union until the Perestroika). Such writers, dubbed "dissidents", could not publish their major works until the 1960s.

But the thaw did not last long. In the 1970s, some of the most prominent authors were not only banned from publishing but were also prosecuted for their anti-Soviet sentiments, or for parasitism. Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the country. Others, such as Nobel Prize–winning poet Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996); novelists Vasily Aksyonov (1932–2009), Eduard Limonov (1943–2020), Sasha Sokolov (1943–) and Vladimir Voinovich (1932–2018); and short-story writer Sergei Dovlatov (1941–1990), had to emigrate to the West, while Oleg Grigoriev (1943–1992) and Venedikt Yerofeyev (1938–1990) "emigrated" to alcoholism. Their books were not published officially until the perestroika period of the 1980s, although fans continued to reprint them manually in a manner called "samizdat" (self-publishing).

Popular Soviet genres[edit source]

Children's literature in the Soviet Union counted as a major genre because of its educational role. A large share of early-Soviet children's books were poems: Korney Chukovsky (1882–1969), Samuil Marshak (1887–1964) and Agnia Barto (1906–1981) were among the most read poets. "Adult" poets, such as Mayakovsky and Sergey Mikhalkov (1913–2009), contributed to the genre as well. Some of the early Soviet children's prose consisted of loose adaptations of foreign fairy-tales unknown in contemporary Russia. Alexey N. Tolstoy (1882–1945) wrote Buratino, a light-hearted and shortened adaptation of Carlo Collodi's Pinocchio. Alexander Volkov (1891–1977) introduced fantasy fiction to Soviet children with his loose translation of L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published as The Wizard of the Emerald City in 1939, and then wrote a series of five sequels, unrelated to Baum. Other notable authors include Nikolay Nosov (1908–1976), Lazar Lagin (1903–1979), Vitaly Bianki (1894–1959) and Vladimir Suteev (1903–1993).

While fairy tales were relatively free from ideological oppression, the realistic children's prose of the Stalin era was highly ideological and pursued the goal to raise children as patriots and communists. A notable writer in this vein was Arkady Gaydar (1904–1941), himself a Red Army commander (colonel) in Russian Civil War: his stories and plays about Timur describe a team of young pioneer volunteers who help the elderly and resist hooligans. There was a genre of hero-pioneer story that bore some similarities with Christian genre of hagiography. In the times of Khrushchov (First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964) and of Brezhnev (in power 1966–1982), however, the pressure lightened. Mid- and late-Soviet children's books by Eduard Uspensky, Yuri Entin, Viktor Dragunsky bear no signs of propaganda. In the 1970s many of these books, as well as stories by foreign children's writers, were adapted into animation.

Soviet Science fiction, inspired by scientistic revolution, industrialisation, and the country's space pioneering, was flourishing, albeit in the limits allowed by censors. Early science fiction authors, such as Alexander Belyayev, Grigory Adamov, Vladimir Obruchev, Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy, stuck to hard science fiction and regarded H. G. Wells and Jules Verne as examples to follow. Two notable exclusions from this trend were Yevgeny Zamyatin, author of dystopian novel We, and Mikhail Bulgakov, who, while using science fiction instrumentary in Heart of a Dog, The Fatal Eggs and Ivan Vasilyevich, was interested in social satire rather than scientistic progress. The two have had problems with publishing their books in Soviet Union.

Since the thaw in the 1950s Soviet science fiction began to form its own style. Philosophy, ethics, utopian and dystopian ideas became its core, and Social science fiction was the most popular subgenre.[18] Although the view of Earth's future as that of utopian communist society was the only welcome, the liberties of genre still offered a loophole for free expression. Books of brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, and Kir Bulychev, among others, are reminiscent of social problems and often include satire on contemporary Soviet society. Ivan Yefremov, on the contrary, arose to fame with his utopian views on future as well as on Ancient Greece in his historical novels. Strugatskies are also credited for the Soviet's first science fantasy, the Monday Begins on Saturday trilogy. Other notable science fiction writers included Vladimir Savchenko, Georgy Gurevich, Alexander Kazantsev, Georgy Martynov, Yeremey Parnov. Space opera was less developed, since both state censors and serious writers watched it unfavorably. Nevertheless, there were moderately successful attempts to adapt space westerns to Soviet soil. The first was Alexander Kolpakov with "Griada", after came Sergey Snegov with "Men Like Gods", among others.

A specific branch of both science fiction and children's books appeared in mid-Soviet era: the children's science fiction. It was meant to educate children while entertaining them. The star of the genre was Bulychov, who, along with his adult books, created children's space adventure series about Alisa Selezneva, a teenage girl from the future. Others include Nikolay Nosov with his books about dwarf Neznayka, Evgeny Veltistov, who wrote about robot boy Electronic, Vitaly Melentyev, Vladislav Krapivin, Vitaly Gubarev.

Mystery was another popular genre. Detectives by brothers Arkady and Georgy Vayner and spy novels by Yulian Semyonov were best-selling,[19] and many of them were adapted into film or TV in the 1970s and 1980s.

Village prose is a genre that conveys nostalgic descriptions of rural life. Valentin Rasputin’s 1976 novel, Proshchaniye s Matyoroy (Farewell to Matyora) depicted a village faced with destruction to make room for a hydroelectric plant.[20]

Historical fiction in the early Soviet era included a large share of memoirs, fictionalized or not. Valentin Katayev and Lev Kassil wrote semi-autobiographic books about children's life in Tsarist Russia. Vladimir Gilyarovsky wrote Moscow and Muscovites, about life in pre-revolutionary Moscow. The late Soviet historical fiction was dominated by World War II novels and short stories by authors such as Boris Vasilyev, Viktor Astafyev, Boris Polevoy, Vasil Bykaŭ, among many others, based on the authors' own war experience. Vasily Yan and Konstantin Badygin are best known for their novels on Medieval Rus, and Yury Tynyanov for writing on Russian Empire. Valentin Pikul wrote about many different epochs and countries in an Alexander Dumas-inspired style. In the 1970s there appeared a relatively independent Village Prose, whose most prominent representatives were Viktor Astafyev and Valentin Rasputin.

Any sort of fiction that dealt with the occult, either horror, adult-oriented fantasy or magic realism, was unwelcome in Soviet Russia. Until the 1980s very few books in these genres were written, and even fewer were published, although earlier books, such as by Gogol, were not banned. Of the rare exceptions, Bulgakov in Master and Margarita (not published in author's lifetime) and Strugatskies in Monday Begins on Saturday introduced magic and mystical creatures into contemporary Soviet reality to satirize it. Another exception was early Soviet writer Alexander Grin, who wrote romantic tales, both realistic and fantastic.

Post-Soviet era[edit source]

The end of the 20th century proved a difficult period for Russian literature, with relatively few distinct voices. Although the censorship was lifted and writers could now freely express their thoughts, the political and economic chaos of the 1990s affected the book market and literature heavily. The book printing industry descended into crisis, the number of printed book copies dropped several times in comparison to Soviet era, and it took about a decade to revive.

Among the most discussed authors of this period were Victor Pelevin, who gained popularity with first short stories and then novels, novelist and playwright Vladimir Sorokin, and the poet Dmitry Prigov. A relatively new trend in Russian literature is that female short story writers Tatyana Tolstaya or Lyudmila Petrushevskaya, and novelists Lyudmila Ulitskaya or Dina Rubina have come into prominence. The tradition of the classic Russian novel continues with such authors as Mikhail Shishkin and Vasily Aksyonov.

Detective stories and thrillers have proven a very successful genre of new Russian literature: in the 1990s serial detective novels by Alexandra Marinina, Polina Dashkova and Darya Dontsova were published in millions of copies. In the next decade Boris Akunin who wrote more sophisticated popular fiction, e.g. a series of novels about the 19th century sleuth Erast Fandorin, was eagerly read across the country.

Science fiction was always well selling, albeit second to fantasy, that was relatively new to Russian readers. These genres boomed in the late 1990s, with authors like Sergey Lukyanenko, Nick Perumov, Maria Semenova, Vera Kamsha, Alexey Pekhov, Anton Vilgotsky and Vadim Panov. A good share of modern Russian science fiction and fantasy is written in Ukraine, especially in Kharkiv,[21] home to H. L. Oldie, Alexander Zorich, Yuri Nikitin and Andrey Valentinov. Many others hail from Kyiv, including Marina and Sergey Dyachenko and Vladimir Arenev. Significant contribution to Russian horror literature has been done by Ukrainians Andrey Dashkov and Alexander Vargo.

Russian poetry of that period produced a number of avant-garde greats. The members of the Lianosovo group of poets, notably Genrikh Sapgir, Igor Kholin and Vsevolod Nekrasov, who previously chose to refrain from publication in Soviet periodicals, became very influential, especially in Moscow, and the same goes for another masterful experimental poet, Gennady Aigi. Also popular were poets following some other poetic trends, e.g. Vladimir Aristov and Ivan Zhdanov from Poetry Club and Konstantin Kedrov and Elena Katsuba from DOOS, who all used complex metaphors which they called meta-metaphors. In St. Petersburg, members of New Leningrad Poetry School that included not only the famous Joseph Brodsky but also Victor Krivulin, Sergey Stratanovsky and Elena Shvarts, were prominent first in the Soviet-times underground – and later in mainstream poetry.

Some other poets, e.g. Sergey Gandlevsky and Dmitry Vodennikov, gained popularity by writing in a retro style, which reflected the sliding of newly written Russian poetry into being consciously imitative of the patterns and forms developed as early as in the 19th century.

21st century[edit source]

In the 21st century, a new generation of Russian authors appeared differing greatly from the postmodernist Russian prose of the late 20th century, which lead critics to speak about “new realism”.[22] Having grown up after the fall of the Soviet Union, the "new realists" write about every day life, but without using the mystical and surrealist elements of their predecessors.

The "new realists" are writers who assume there is a place for preaching in journalism, social and political writing and the media, but that “direct action” is the responsibility of civil society.[citation needed]

Leading "new realists" include Ilja Stogoff, Zakhar Prilepin, Alexander Karasyov, Arkady Babchenko, Vladimir Lorchenkov and Alexander Snegiryov.[23]

External influences[edit source]

British romantic poetry[edit source]

Scottish poet Robert Burns became a ‘people's poet’ in Russia. In Imperial times the Russian aristocracy were so out of touch with the peasantry that Burns, translated into Russian, became a symbol for the ordinary Russian people. A new translation of Burns, begun in 1924 by Samuil Marshak, proved enormously popular selling over 600,000 copies.[24][25]

Lord Byron was a major influence on almost all Russian poets of the Golden Era, including Pushkin, Vyazemsky, Zhukovsky, Batyushkov, Baratynsky, Delvig and, especially, Lermontov.[26]

French literature[edit source]

Writers such as Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac were widely influential.[27] Also, Jules Verne inspired several generations of Russian science fiction writers.

Abroad[edit source]

Russian literature is not only written by Russians. In the Soviet times such popular writers as Belarusian Vasil Bykaŭ, Kyrgyz Chinghiz Aitmatov and Abkhaz Fazil Iskander wrote some of their books in Russian. Some renowned contemporary authors writing in Russian have been born and live in Ukraine (Andrey Kurkov, H. L. Oldie, Maryna and Serhiy Dyachenko) or Baltic States (Garros and Evdokimov, Max Frei). Most Ukrainian fantasy and science fiction authors write in Russian,[28] which gives them access to a much broader audience, and usually publish their books via Russian publishers such as Eksmo, Azbuka and AST.

A number of prominent Russian authors such as novelists Mikhail Shishkin, Rubén Gallego, Julia Kissina, Svetlana Martynchik and Dina Rubina, poets Alexei Tsvetkov and Bakhyt Kenjeev, though born in USSR, live and work in West Europe, North America or Israel.[29][page needed]

Themes in Russian books[edit source]

Suffering, often as a means of redemption, is a recurrent theme in Russian literature. Fyodor Dostoyevsky in particular is noted for exploring suffering in works such as Notes from Underground and Crime and Punishment. Christianity and Christian symbolism are also important themes, notably in the works of Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and Chekhov. In the 20th century, suffering as a mechanism of evil was explored by authors such as Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago. A leading Russian literary critic of the 20th century Viktor Shklovsky, in his book, Zoo, or Letters Not About Love, wrote, "Russian literature has a bad tradition. Russian literature is devoted to the description of unsuccessful love affairs."

Russian Nobel laureates in Literature[edit source]

- Ivan Bunin (1933)

- Boris Pasternak (1958)

- Mikhail Sholokhov (1965)

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1970)

- Joseph Brodsky (1987)

- Svetlana Alexievich (2015)

See also[edit source]

References[edit source]

- ^ Moscow International Book Fair. Academia-rossica.org. Retrieved on 2012-06-17.

- ^ The Moscow Times The most reading country in the world? Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rivkin-Fish, Michele R.; Trubina, Elena (2010). Dilemmas of Diversity After the Cold War: Analyses of "Cultural Difference" by U.S. and Russia-Based Scholars. Woodrow Wilson Center.

"When mass illiteracy was finally liquidated in the first half of the twentieth century, the proud self-image of Russians as “the most reading nation in the world” emerged – where reading meant, and still means for many, the reading of literature". - ^ Letopisi: Literature of Old Rus'. Biographical and Bibliographical Dictionary. ed. by Oleg Tvorogov. Moscow: Prosvescheniye ("Enlightenment"), 1996. (Russian: Летописи// Литература Древней Руси. Биобиблиографический словарь / под ред. О.В. Творогова. – М.: Просвещение, 1996.)

- ^ Terras, pp. 221–223

- ^ Terras, pp. 474–477

- ^ Lang, D.M. “Boileau and Sumarokov: The Manifesto of Russian Classicism.” The Modern Language Review, Vol. 43, No. 4, 1948, p. 502

- ^ Lang, D.M. “Boileau and Sumarokov: The Manifesto of Russian Classicism.” The Modern Language Review, Vol. 43, No. 4, 1948, p. 500

- ^ Terras, pp. 365–366

- ^ Offord, Derek (2005). "Denis Fonvizin and the Concept of Nobility: An Eighteenth-century Russian Echo of a Western Debate". European History Quarterly. 35 (1): 10. doi:10.1177/0265691405049200. S2CID 145305528.

- ^ Soviet literature: problems and people K. Zelinsky, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1970. p. 167

- ^ A. Ovcharenko. Socialist realism and the modern literary process. Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1978. p. 120

- ^ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrey-Bely

- ^ "Design Template". Jul 30, 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-07-30.

- ^ a b "Подводя итоги XX столетия: книгоиздание. Бестселлер – детище рекламы". compuart.ru.

- ^ Soviet literature: problems and people K. Zelinsky, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1970. p. 135

- ^ "Фадеев Александр Александрович". Hrono.info. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Science fiction – literature and performance". Britannica.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Sofya Khagi: Boris Akunin and Retro Mode in Contemporary Russian Culture, Toronto Slavic Quarterly

- ^ "Prose poem". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- ^ "Kharkov Ukraine". Ukrainetravel.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Аристов, Денис (Aristov, Denis) "О природе реализма в современной русской прозе о войне (2000-е годы)" (PDF). Journal Perm State Pedagogical University. 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Yevgeni Popov (21 April 2009). "Who can follow Gogol's footsteps" (PDF). Matec.ru. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Classical Music on CD, SACD, DVD and Blu-ray : Russian Settings of Robert Burns. Europadisc (2009-01-26). Retrieved on 2012-06-17.

- ^ Peter Henry. "Sure way of getting Burns all wrong". Archived from the originalon December 11, 2004. Retrieved 2009-06-10.. standrews.com

- ^ Розанов. Байронизм // Словарь литературных терминов. Т. 1. – 1925 (текст). Feb-web.ru. Retrieved on 2012-06-17.

- ^ Stone, Jonathan (2013). Historical Dictionary of Russian Literature. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 53. ISBN 9780810871823.

- ^ Oldie, H.L.; Dyachenko, Marina and Sergey; Valentinov, Andrey (2005). Пять авторов в поисках ответа (послесловие к роману "Пентакль") [Five authors in search for answers (an afterword to Pentacle)] (in Russian). Moscow: Eksmo. ISBN 5-699-09313-3.

Украиноязычная фантастика переживает сейчас не лучшие дни. ... Если же говорить о фантастике, написанной гражданами Украины в целом, независимо от языка (в основном, естественно, на русском), – то здесь картина куда более радужная. В Украине сейчас работают более тридцати активно издающихся писателей-фантастов, у кого регулярно выходят книги (в основном, в России), кто пользуется заслуженной любовью читателей; многие из них являются лауреатами ряда престижных литературных премий, в том числе и международных.

Speculative fiction in Ukrainian is living through a hard time today ... Speaking of fiction written by Ukrainian citizens, regardless of language (primarily Russian, of course), there's a brighter picture. More than 30 fantasy and science fiction writers are active here, their books are regularly published (in Russia, mostly), they enjoy the readers' love they deserve; many are recipients of prestigious literary awards, including international. - ^ Katsman, Roman (2016). Nostalgia for a Foreign Land: Studies in Russian-Language Literature in Israel. Boston: Academic Studies Press. ISBN 978-1618115287.

Bibliography[edit source]

- Terras, Victor (1985). Handbook of Russian Literature. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press ISBN 0300048688

- Gorlin, Mikhail (November 1946). "The interrelation of painting and literature in Russia". The Slavonic and East European Review. 25 (64).

External links[edit source]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Russian literature |

- Encyclopedia of Soviet Writers

- An Outline of Russian Literature by Maurice Baring at Project Gutenberg

- Maxim Moshkov's E-library of Russian literature (in Russian)

- Contemporary Russian Poets Database (in English)

- Contemporary Russian Poets in English translation

- A bilingual anthology of Russian verse

- La Nuova Europa: international cultural journal about Russia and East of Europe

- Information and Critique on Russian Literature

- History of Russian literature Brief summary

- Russian Literary Resources by the Slavic Reference Service

- Search Russian Books (in Russian)

- Philology in Runet. A special search through the sites devoted to the Old Russian literature.

- Russian literary magazine "Reflection of the Absurd"

- Публичная электронная библиотека Е.Пескина

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.