- 함재봉(오른쪽) 아산정책연구원장이 지난해 2월 미국 하버드대 케네디 스쿨 벨퍼 센터 초청 회의에 참석해 발언하고 있다. 함 원장은 이 자리에서 미중 사이의 한국의 전략적 딜레마에 대해 발표했다. 아산정책연구원 제공.

-----------

오늘 나는 한 이채로운 지식인을 살펴보려 한다. 정치학자 함재봉이 그다. 그가 왜 이채로운 지식인일까. 두 가지 점에서 그렇다. 첫째, 그는 미국에서 고교와 대학을 다녔고, 박사학위를 마친 다음 한국으로 돌아와 가르치고 연구했다. 둘째, 이런 지적 배경에서 그가 정작 내놓은 것은 유교사상과 민주주의를 결합한 유교민주주의론이다. 서구 교육에 오랫동안 세례 받았음에도 불구하고 전통사상인 유교를 앞세운 그의 연구들이 내겐 흥미롭고 이채로웠다.

지난 100년의 지성사를 돌아볼 때 우리 지식사회에선 학파 또는 그룹들이 존재했다. 보수적 경제학자들로 이뤄진 ‘서강학파’, 진보적 경제학자들이 주축이 된 ‘학현학파’, 진보적 문예이론을 내세운 ‘창비(창작과 비평) 그룹’, 자유주의 문예이론이 두드러진 ‘문지(문학과 지성) 그룹’은 대표적인 사례들이었다.- 진보적 사회학을 내건 ‘산사연’(산업사회연구회)이나 마르크스주의에 주력한 ‘서사연’(서울사회과학연구소)을 기억하는 이들도 있을 것이다.

이러한 학파들 가운데 1990년대 후반과 2000년대 초반 잡지 ‘전통과 현대’에서 활동한 그룹이 있었다. 이들은 전통사상인 유교가 갖는 의미를 재발견하고 현대화하려는 지적 기획을 펼쳐 보였다. ‘전통과 현대’는 사회학자 전병재가 편집인을, 정치학자 함재봉이 편집주간을 맡았고, 유교자본주의론과 유교민주주의론을 주창해 지식사회 안에서 상당한 화제를 불러 모았다. 이채로운 지식인 함재봉을 다루는 까닭은 여기에 있다.

◇전통과 탈근대 사이에서

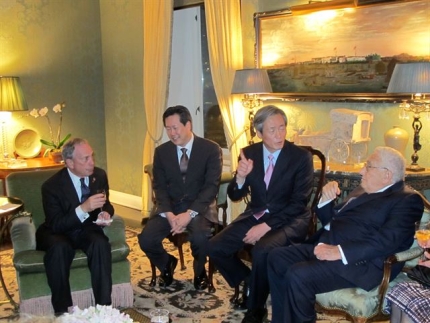

함재봉은 1958년 미국 보스턴에서 태어났다. 부친 함병춘의 유학과 외교관 생활로 어린 시절부터 미국과 한국을 오가며 성장했다. 칼튼 칼리지에서 경제학을 공부했고, 존스홉킨스대에서 정치학 박사를 받았다. 연세대에서 정치학을 가르치다 프랑스 파리 유네스코(UNESCO) 본부 사회과학 국장을 맡았다. 이후 미국 남캘리포니아대 교수와 랜드연구소 선임 정치학자를 거쳐 현재 아산정책연구원 이사장 및 원장으로 일하고 있다. 원본보기미국 유학파 출신인 함재봉 원장은 미국 주요 인사들과의 교류도 활발하다. 지난 2013년 헨리 키신저 전 미 국무장관의 뉴욕 자택에서 열린 만찬에 참석해 대화하고 있다. 왼쪽부터 마이클 블룸버그 전 뉴욕시장, 함 원장, 정몽준 아산정책연구원 명예이사장, 키신저 전 장관. 뉴욕=연합뉴스

원본보기미국 유학파 출신인 함재봉 원장은 미국 주요 인사들과의 교류도 활발하다. 지난 2013년 헨리 키신저 전 미 국무장관의 뉴욕 자택에서 열린 만찬에 참석해 대화하고 있다. 왼쪽부터 마이클 블룸버그 전 뉴욕시장, 함 원장, 정몽준 아산정책연구원 명예이사장, 키신저 전 장관. 뉴욕=연합뉴스

함재봉은 1997년 여름에 창간한 ‘전통과 현대’의 편집주간을 맡으면서 국내 지식사회에서 주목 받기 시작했다. 당시 ‘전통과 현대’의 등장은 앞서 말했듯 상당한 관심을 불러일으켰다. 포스트마르크스주의, 포스트모더니즘, 포스트콜로니얼리즘 등 다양한 ‘포스트주의’가 성행했던 상황에서 전통을 화두로 삼았기 때문이다.

철학자 이승환, 사회학자 유석춘, 정치학자 김병국 등이 참여한 ‘전통과 현대’는 전통주의 내지 보수주의와 가까웠다. 하지만 동시에 ‘전통과 현대’는 그 비판 대상의 하나를 오리엔탈리즘에 맞춤으로써 방어적 국수주의와도 거리를 뒀다. 주요 필자들이 이른바 ‘국내파’가 아닌 ‘유학파’였다는 점도 이채로웠다. ‘전통과 현대’는 한편으로 전통의 재발견과 창조적 계승을 강조하고, 다른 한편으론 보수와 진보에 큰 영향을 미쳐온 서구중심주의를 비판함으로써 서구 이론 및 사상의 일방적 수용에 회의하던 이들에게 공감을 불러 모았다.

‘탈근대와 유교’(1998)는 이즈음 발표한 함재봉의 첫 저작이다. ‘한국 정치담론의 모색’이라는 부제가 달린 이 책에서 그는 포스트모더니즘과 유교라는 사상적 프리즘을 통해 근대사회와 한국사회의 논리에 대한 심층적 분석을 시도했다.

함재봉은 스스로 보수주의자로서의 정체성을 갖고 있다. 그의 보수주의는 ‘철학적 보수주의’에 가깝다. 철학적 보수주의는 후기 루드비히 비트겐슈타인, 한스-게오르크 가다머, 마이클 오크숏으로 대표된다. 이들은 인간의 불완전성에 주목하고, 사회 문제들을 대화로 풀고자 한다. 전통을 중시한다는 점을 제외한다면, 이들의 사상은 미셸 푸코와 자크 데리다로 대표되는 포스트모더니즘 철학의 상대주의 인식론과 흡사하다.

주목할 것은 이런 철학적 보수주의와 유교사상이 갖는 친화성이다. 뿌리 깊은 전통주의, 가족·국가를 중시하는 공동체주의, 선차적 중요성이 부여되는 도덕주의, 배움을 바탕으로 한 엘리트주의와 같은 유교사상의 핵심은 철학적 보수주의로부터 먼 거리에 놓인 사유가 아니다. 탈근대와 유교라는 이질적으로 보이는 두 사유 방식 사이에서 함재봉은 한국정치의 생산 및 재생산의 문법을 탐구했다.

◇유교민주주의란 무엇인가

‘유교, 자본주의, 민주주의’는 함재봉이 2000년에 발표한 저작이다. ‘탈근대와 유교’에 이어 이 책에서 그는 유교사상을 자본주의, 민주주의와의 관계 속에서 탐구하고 해석한다. 그가 목표로 삼은 것은 보편사의 흐름 속에서 한국적 정체성에 대한 자각과 정립이다. 그는 말한다.

“유교를 자본주의와 민주주의에 비교해 보는 것은 자본주의와 민주주의를 유교적 토양 위에 정착시키는 작업이며, 자본주의와 민주주의를 유교화시키는 작업이기도 하면서 다른 한편으로는 유교를 보편화시키는 작업이기도 하다.”

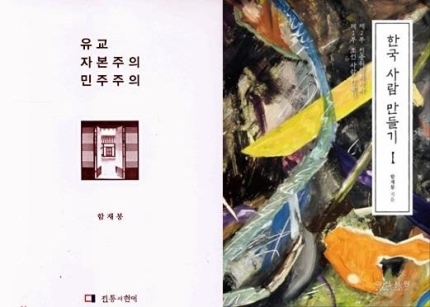

당시 유교에 대한 학문적 관심을 높인 것은 유교자본주의를 둘러싼 토론이었다. 유교자본주의는 국가와 교육의 역할에서 볼 수 있듯 동아시아 경제발전에서 유교적 가치관이 긍정적인 기여를 했다는 점을 부각시켰다. 하지만 이 담론은 1997년 외환위기가 발생하자 ‘정실자본주의’로 불리면서 작지 않은 비판을 받았다. 원본보기함재봉 원장은 유교 사상을 자본주의와 민주주의 이념과 접목시키는 데 노력해왔다. 2000년에 집필한 책 ‘유교, 자본주의, 민주주의’는 그의 대표 저작이다. 최근에는 한국사람의 정체성을 연구한 ‘한국사람 만들기’란 책을 시리즈로 출간하고 있다. 한국일보 자료사진.

원본보기함재봉 원장은 유교 사상을 자본주의와 민주주의 이념과 접목시키는 데 노력해왔다. 2000년에 집필한 책 ‘유교, 자본주의, 민주주의’는 그의 대표 저작이다. 최근에는 한국사람의 정체성을 연구한 ‘한국사람 만들기’란 책을 시리즈로 출간하고 있다. 한국일보 자료사진.

-----------------

유교민주주의란 무엇인가. 유교민주주의란 ‘아시아적 가치’의 하나인 유교를 바탕으로 한 ‘비자유주의적 민주주의’를 지칭한다. 함재봉은 말한다.

“유교민주주의란 다름 아니라 종교, 계급, 인종, 지역 간의 갈등을 긍정하거나 활용하지 않고 보다 공동체주의적인 민주주의를 모색하고자 하는 문제의식에서 출발한다. 한국사회의 도덕적 합의를 바탕으로 한 강력한 통합력을 유지시키면서 건설적인 방향으로 유도하기 위한 제도적 장치를 마련하는 것이 유교민주주의의 핵심이다.”

함재봉은 서구 자유주의가 가져온 사회적 병폐와 도덕적 해이를 우려한다. 그리하여 이 자유주의를 도덕·가족·국가를 중시하는 유교적 공동체주의로 대체하려는 정치담론으로서의 유교민주주의를 제시한다. 유교민주주의는 서구 자유민주주의와는 상이한, 동아시아에서 관찰할 수 있는 담론이자 현실이라는 게 그의 주장이다. 지성사적으로 유교민주주의는 아시아적 가치론의 정치학인 셈이다.

이러한 유교민주주의론에 대해선 당시 상반된 평가가 이뤄졌다. 한편에서 유교민주주의론은 동아시아 정치의 역사적 특징을 주목함으로써 서구 정치이론의 무분별한 적용에 경종을 울렸다. 근대화론이든 마르크스주의든 서구 이론이 서구중심주의로부터 자유롭지 못하다는 점에서 유교민주주의론의 문제제기는 음미할 만한 내용을 담고 있었다.

다른 한편에선 유교 사상이 자유주의를 대신할 수 있는 정치적 대안이 될 수 있는지에 대한 회의 또한 작지 않았다. 유교는 전통주의·도덕주의·공동체주의의 사상인 동시에 권위주의·국가주의·가부장주의의 사상이라는 게 그 비판의 핵심이었다. 개인적으로 나는 공감보다 비판에 더 동의했다. 하지만 한국정치의 특수성을 유교사상에서 찾으려는 함재봉의 노력은 평가할 만하다고 생각했다.

◇지식사회의 미래

최근 함재봉은 ‘한국 사람 만들기’라는 야심만만한 제목을 단 책의 저자로 돌아왔다. 그는 ‘조선 사람’이 지난 20세기를 거쳐 ‘한국 사람’으로 변화했다는 점을 주목한다. 이 ‘한국 사람’의 정체성은 ‘친중위정척사파’, ‘친일개화파’, ‘친미기독교파’, ‘친소공산주의파’, ‘인종적 민족주의파’의 다섯 가지로 나눠볼 수 있다는 게 그의 생각이다. 한국 사람의 계보학을 다룬 이 저작은 이제까지 두 권(‘친중위정척사파’와 ‘친일개화파’)으로 나왔고, 앞으로 계속 발표할 것이라고 한다. 원본보기함재봉 원장이 지난해 3월 서울 한남동 블루스퀘어에서 열린 네이버 주최 ‘열린연단’의 연사자로 초청돼 강의를 하고 있다. 아산정책연구원 제공.

원본보기함재봉 원장이 지난해 3월 서울 한남동 블루스퀘어에서 열린 네이버 주최 ‘열린연단’의 연사자로 초청돼 강의를 하고 있다. 아산정책연구원 제공.

완성된 저작이 아닌 만큼 여기서 ‘한국 사람 만들기’를 평가하기란 쉽지 않다. 분명한 것은 함재봉의 연구 태도가 주목 받아 마땅하다는 점이다. 우리 사회에서 인간과 사회 탐구를 직업으로 하는 이들에게 서양과 동양의 거리, 서구사회와 한국사회의 차이는 그 공통점 못지않게 중요한 인식 대상이다. 세계사적 보편성 속에서 우리 사회의 특수성을 주목하려는 함재봉의 학문적 태도는 바람직한 것으로 보인다.

비서구사회에서 살아가는 지식인들은 자기 삶과 사회를 이해하는 데 서구 이론 및 사상을 어디까지, 그리고 어떻게 수용해야 할까. 서양중심주의와 동양중심주의는 그 대안이 될 수 없다. 이 둘을 모두 넘어서서 보편성과 특수성을 아우르는 담론 및 분석을 천착하는 것은 우리 지식사회의 미래에 부여된 중대한 과제라고 나는 생각한다.

김호기 연세대 사회학과 교수

※ ‘김호기의 100년에서 100년으로’는 지난 한 세기 우리나라 대표 지성과 사상을 통해 한국사회의 미래를 생각하는 연재입니다. 다음주에는 한용운의 ‘님의 침묵’이 소개됩니다.

▶한국일보 [페이스북] [카카오 친구맺기]

▶네이버 채널에서 한국일보를 구독하세요!

이 기사는 언론사에서 생활 섹션으로 분류했습니다.

구독

메인에서 바로 보는 언론사 편집뉴스 지금 바로 구독해보세요!

좋아요4

훈훈해요0

슬퍼요0

화나요4

후속기사 원해요2

이 기사를 메인으로 추천 2

모두에게 보여주고 싶은 기사라면?beta이 기사를 메인으로 추천 버튼을 눌러주세요. 집계 기간 동안 추천을 많이 받은 기사는 네이버 메인 자동 기사배열 영역에 추천 요소로 활용됩니다.레이어 닫기

김호기의 100년에서 100년으로더보기

구독81명

뿌리 깊은 유교 사상서 한국 민주주의 특수성을 찾다4일전

치열했던 육사의 삶을 그대로 투영한 시, 깊은 울림을 주다2019.02.11

‘행동하는 양심’ 증명한 DJ... 한반도 평화의 길을 열다2019.01.28

이 기사의 댓글 정책은 한국일보가 결정합니다.안내

전체 댓글21새로고침

내 댓글

댓글 상세 현황

현재 댓글21

uber****

유교와 민주주의는 완전히 방향이 다르다. 섞이기 힘들다. 그냥 유교를 좋아하는 3류 학자의 현학적 구상일 뿐.

2019-02-18 08:55:15신고

답글2

공감/비공감공감13비공감2

anfa****

그놈의 유교사상 때문에 동양의 발전은 100년이나 느려졌지.

2019-02-18 13:52:31신고

답글0

공감/비공감공감5비공감0

forc****댓글모음

그놈의 우리식 민주주의 ㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋ

2019-02-18 10:24:43신고

답글0

공감/비공감공감3비공감0

kizk****댓글모음

나는 친미불교... 유교, 기독교, 사회,공산주의 다 포함 안됨. 카테고리란 게 댁 맘대로 선긋기가 아님.

2019-02-18 13:55:56신고

답글0

공감/비공감공감2비공감0

knte****댓글모음

유교는 왕조지배체제 이데올로기얼뿐이다 말도 안되는 논리전개를 하지마라

2019-02-18 09:53:02신고공감

Because we are Lazarus, and we live.

뿌리 깊은 유교 사상서 한국 민주주의 특수성을 찾다

기사입력2019.02.18

[김호기의 100년에서 100년으로] <50> 함재봉의 ‘유교, 자본주의, 민주주의’