"한국의 간디" - 오강남의 함석헌 이야기 : 네이버 카페

"한국의 간디" - 오강남의 함석헌 이야기 | 자유게시판

2018.12.16. 17:59

2018.12.16. 17:59soft103a(soft****)

나눔회원

https://cafe.naver.com/yooyoonjn/1597

==============

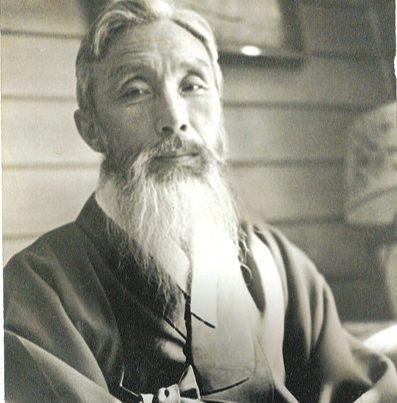

함석헌

-생명, 평화, 민주, 비폭력 등을 위해 힘쓴 ‘한국의 간디’

“하나님은 다른 데선 만날 데가 없고, 우리 마음속에, 생각하는 데서만 만날 수가 있다. 자기를 존경함은 자기 안에 하나님을 믿음이다……그것이 자기발견이다”

들어가며

다석 류영모 선생이 가장 아끼던 제자가 함석헌 선생이었고, 함석헌 선생이 가장 존경하던 스승이 류영모 선생이었다. 함석헌 선생은 다석의 1주기에 다석 선생의 제자들이 다석 선생의 집에 모였을 때 “내가 부족하지만 이만큼 된 것도 선생님이 계셨기 때문이라는 것을 잘 안다”고 했다.

두 분은 여러 면에서 비슷하면서도 대조적이었다. 우선 11살의 차이였지만 생몰 일자가 거의 같다. 똑같이 3월 13일에 출생하고 돌아가신 날도 류영모 선생님은 2월 3일 저녁, 함석헌 선생님은 2월 4일 새벽으로 몇 시간 차이일 뿐이다. 그야말로 ‘의미 있는 우연’이라고 할까? 두 분 모두 흰 두루마기를 즐겨 입으셨고, 수염을 기르셨다.

그러나 무엇보다 중요한 것은 두 분의 근본 사상이 여러 면에서 같았다는 사실이다. 두 분 모두 2008년 서울에서 열린 세계 철학자 대회에서 한국을 대표하는 사상가로 소개되었다. 필자로서는 류영모 선생을 뵙지 못한 것이 ‘천추의 한’이라면, 함석헌 선생은 여러 번 뵙고, 1979년 캐나다 에드먼튼에 살 때 필자의 집에 유하시면서 필자가 근무하던 알버타 대학교에서 교민을 대상으로 강연도 하시고 종교학과 교수들과 대담도 하실 수 있도록 주선한 것은 더 없는 영광이라 생각된다.

대조적인 점은 류영모 선생에 비해 함석헌 선생은 키도 크시고 외모도 출중하셨다. 그러나 무엇보다 중요한 것은 류영모 선생이 생의 후반에서 비교적 은둔적이고 금욕적인 면이 강했던 데 비해 함석헌 선생은 여러 사람과 함께 어울려 한국 민주화에 직접 참여하시는 등 사회 개혁에도 힘을 많이 쓰셨던 점이라고 볼 수 있다.신비주의 전통에서 즐겨 쓰는 용어를 빌리면 함석헌 선생은 ‘행동하는 신비주의자’라 할 수 있다.

마침 함석헌 선생이 “나는 왜 퀘이커교도가 되었는가”하는 제목의 자서전적인 글을 쓰셨는데, 그것을 토대로 그의 삶을 재구성해 본다.

그의 삶

신천 함석헌咸錫憲(1901~1989)은 (여기서부터 존칭 생략) 평안북도 황해 바닷가 용천에서 아버지 함형택과 어머니 김형도 사이의 3남2녀 중 누님 아래 둘째로 태어났다. 5세경 누님이 배우는 천자문을 옆에서 듣고 모두 외었다. 여섯 살에 기독교 계통의 사립 덕일 소학교에 입학하고 긴 댕기머리를 잘랐다. 함석헌에 의하면 전통 종교가 창조적인 생명력을 잃은 형식적 전통에 불과할 때 ‘바닷가 상놈’의 고장으로 알려진 자기 마을에 새로 들어온 기독교는 사람들에게 희망과 의욕을 넣어주었다고 한다. 그는 기독교 계통 사립 초등학교에서‘하느님과 민족’을 배울 수 있었던 것을 다행으로 여겼다.

“아홉 살 때 나라가 일본한테 아주 망하고 어른들이 예배당에서 통곡하는 것을 보았을 때 어린 마음에 크게 충격을 받았”으나 믿음으로 인해 아주 낙담하지는 않았다고 한다. 후일 함석헌은 자기가 “열세 살까지 지금 생각하기에도 순진한 기독 소년이었다”고 고백한다. 14세에 양시 공립 보통학교에 입학하고, 16세에 졸업한 다음, 평양고등보통학교에 입학했다. 이것은 나중 의사가 될 목적이었다. 공립학교에 다니면서 순진성이 많이 없어지고 과학을 배우면서 성경에 대한 의심이 생기기 시작했다고 한다.

평양고보 2학년 17세에 한 살 아래의 황득순과 결혼했다. 3학년 때인 1919년 3·1운동에 참가했다가 학업을 중단하고 수리조합 사무원, 소학교 선생으로 일하기도 했다. 그해 11월 장남 국용이 출생하고 2년 후 장녀 은수가 태어났다. 그는 모두 2남 3녀를 두었다. 그는 이때를 회고하며 “집에서 2년 동안을 있노라니 운동 이후 폭풍처럼 일어나는 자유의 물결과 교육열 속에서 젊은 놈의 가슴이 타올라 날마다 빈둥빈둥 놀면서 썩고만 있을 수가 없었다”고 했다.

1921년 21세에 다시 학업을 계속하려고 서울로 올라왔지만 4월이라 입학 시기가 지나 어디에도 받아주는 데가 없었다. 그러다가 우연히 길가에서 집안 형 되는 함석규 목사를 만나, 그가 써주는 편지를 가지고 정주 오산학교에 가서 3학년에 편입되었다. 그해 여름이 지나고 류영모가 교장으로 부임하고, 9월 개학식 때 함석헌은 처음으로 류영모를 만나게 되었다. 함석헌에 의하면 그는 류영모의 영향으로 의사가 되겠다는 꿈을 접고 처음으로 한국이 필요로 하는 뭔가를 찾기 시작하고, 또 류영모로부터 노자도 처음으로 알게 되었다. 그 결과 “남을 따라 마련된 종교를 믿기보다는 좀 더 참된 믿음을 요구하는 마음이” 생기기 시작했다. 그러나 그는 교회에서 이런 요구를 충족시키지 못한다는 것을 깨닫게 되었다. 더욱이 교회가 ‘점점 현실에서 먼 신조주의信條主義’, 교리중심주의로 굳어지게 되자 교회에 대해 비판적이 되기 시작했다. 오산학교와 류영모의 영향을 보여주는 대목이다.

함석헌은 1923년 일본 도쿄로 유학을 갔다. 그해 9월에 난 대지진으로 도쿄시의 3분 2가 타버렸다. 일본 정치가들은 민심수습책으로 한국인들이 폭동을 계획한다는 유언비어를 퍼트려 한국인 약 6천명이 학살되었다.이를 본 함석헌은 “기독교를 가지고 내 민족을 건질 수 있을까?” 번민하기 시작했다. 현실적으로는 사회주의 혁명밖에 다른 길이 없다고 생각되었지만 그렇다고 도덕을 무시하는 사회주의운동에 가담할 수도 없었다.오래 동안 기독교와 사회주의 사이에서 고민하게 되었다.

한국 형편으로는 교육이 무엇보다 시급하다는 생각에서 일본 유학을 결심한 그 본래의 의도대로 1924년 지금의 교육대학에 해당하는 도쿄 고등사범학교에 들어갔다. 새로 입학한 기쁨에 교회를 찾아가다가 동갑내기1년 선배인 김교신金敎臣을 만나고, 김교신이 우치무라의 성경연구회에 나간다는 것을 알게 되었다. 우치무라는 오산학교에서 류영모 선생에게서 이미 들어 알고 있던 인물이었다. 그 당시에는 우치무라가 생존인물인지도 몰랐는데, 김교신을 통해 그가 도쿄에 살면서 성경을 가르친다는 사실을 알고 ‘놀라움과 반가움’을 금할 수 없었다. 함석헌은 존경하는 스승 류영모가 언급한 인물이라는 사실 한 가지만으로 우치무라의 무교회 모임에 참석하기 시작했다.

그 모임에서는 별도의 예배형식이 없이 성경을 읽고 십자가에 의한 속죄를 강조하며 해석하는 것이 주된 일이었다고 한다. 여기서 함석헌은 “성경이란 이렇게 읽어 나갈 것이다” 하는 확신이 들었다. 그러면서 사회주의와 기독교 사이에서 머뭇거리던 번민에서 벗어나 ‘크리스챤으로 나갈 것’을 결심하게 되었다.

1928년 교육대학을 졸업하고 귀국, 오산학교로 돌아와 역사 선생으로 일했다. 그러나 역사 선생이 된 것을 후회하게 되었다. 역사란 것이 ‘온통 거짓말투성이’일 뿐 아니라 한국 역사가 ‘비참과 부끄럼의 연속’이어서,학생들에게 그대로 가르치자니 어린 마음에 ‘자멸감과 낙심만’ 심어줄 것 같고, 다른 사람들처럼 과장하고 꾸미려니 양심이 허락하지 않았기 때문이었다. 고민에 고민, 결국 자기에게는 세 가지 버릴 수 없는 것이 있음을 확인했다. 첫째 한민족으로서 민족적 전통을 버릴 수 없고, 둘째 하느님을 믿는 신앙을 버릴 수 없고, 셋째 영국 역사가 H. G. Wells의 The Outline of History를 읽고, 그 영향으로 받아들인 과학과 세계국가주의를 버릴 수 없었다. 이 셋을 어떻게 조화시킬 수 있을까? 이 셋을 다 살리면서 역사 교육을 할 수는 없을까?

그러던 어느 날 어떻게 된 것인지 문득 한 생각이 떠올랐다. ‘고난의 메시야가 영광의 메시야라면, 고난의 역사는 영광의 역사가 될 수 없느냐?’하는 것이었다. 생각이 여기에 미치자 다시 용기가 나 역사 교수를 계속할 수 있었다. 말하자면 한국 역사의 keynote를 ‘고난suffering’으로 보는 역사관이 확립되고 이런 역사관에 입각해서 한국 역사를 재해석하기로 한 것이다.

그때 앞에서 지적한 것처럼 우치무라의 성서연구모임에 참석했던 유학생들 여섯 명이 귀국하여 성서연구모임을 만들고 ��성서조선聖書朝鮮��이라는 동인지를 발간했는데, 함석헌은 ‘고난’의 견지에서 한국 역사를 새로 조명하는 글을 연재했다. 이것이 ��성서적 입장에서 본 조선 역사��라는 명작이 되어 나왔다. 이 책은 나중��뜻으로 본 한국 역사��라는 이름의 개정판으로 나왔고, 류영모의 맏아들이 번역하여 영문판으로도 나왔다.

오산학교에 10년간 있었는데, 그때는 스스로 ‘십자가 중심 신앙에 충실한 무교회 신자’였다고 했다. 그러나 본래 교파를 싫어하여 무교회라는 것이 생겼는데, 아이러니하게도 무교회도 하나의 교파로 굳어가는 것 같고, 또 우치무라에 대한 개인숭배 태도가 보이기도 하는 것 같아 반감을 느끼고, 더욱이 중요한 것은 자주적으로 생각을 깊이하면서 예수가 내 죄를 대신해서 죽었음을 강조하는 우치무라의 십자가 대속 신앙을 받아들일 수가 없게 되었다. 심정적으로는 무교회주의에서 떠났지만, 그것을 크게 공표하여 부산을 떨 필요를 느끼지 않아 그런대로 몇 년을 지났다.

오산에 있으면서 한국의 구원은 ‘믿음을 중심으로 하는 교육을 통해 농촌을 살려내는 것’이라 생각하고 자기가 오산에 온 것도 이를 실천하기 위함이라고 믿었다. 그러나 1936~1937년 한국인의 민족정신을 말살하려는 일본의 식민지 정책이 점점 가혹해지자 함석헌은 죽을 지언정 이에 맞서야 한다고 하였지만 오산학교 행정자 측은 어쩔 수 없이 타협하는 쪽으로 기울어짐에 따라 그는 평생을 바칠 마음으로 왔던 학교를 떠날 수밖에 없었다. 1938년 봄 “눈물로 교문을 나왔다.”

교문은 나왔지만 차마 학생들을 떠날 수는 없었다. 오산에 머물면서 일요일마다 학생들을 만났다. 그렇게 2년을 보내다가, 후배 김두혁이 평양 시외에서 경영하던 덴마크식 송산농사학교를 넘겨주겠다고 하여 1940년 그리로 갔다. 가자마자 설립자가 독립 운동에 가담했다는 혐의로 검거됨에 따라 함석헌도 덩달아 감옥에 들어가게 되었다. 억울하게 1년간 옥살이를 하고 나오니 아버지도 세상을 떠나고 집안이 말이 아니었다. 고향에서 농사를 짓고 있는데, 1942년 김교신이 ��성서조선��에 실린 「조와弔蛙」라는 우화 때문에 잡지에 관여했던 사람들이 모두 잡혀가는 사건이 터져, 다시 감옥에 들어가 1년의 옥고를 치르고 나왔다. 이 때문에 나중 독립유공자 자격으로 대전 국립묘지에 이장될 수 있게 된 것이다. 출옥 후 다시 농사를 짓고 있는데, 2년 후 해방이 되었다.

함석헌은 이때까지 감옥을 네 번, 그 후로도 세 번 더 들어갔는데, 감옥에 있을 때 얻은 것이 가장 많았다고 한다. 그는 감옥을 ‘인생대학’이라 부르고, 감옥 속에서 불교 경전도 보고, 노자, 장자도 더 읽을 수 있었을 뿐 아니라 ‘어느 정도의 신비적인 체험’도 얻었다고 한다. 이런 경험을 통해 ‘모든 종교는 궁극에 있어서는 하나라는 확신’에 이를 수도 있었다. 함석헌은 감옥에서 깨달은 바를 스스로 다음과 같이 정리했다.

“이것은 단순히 국경선의 변동에만 그치지 않을 것이다. 인간 사회의 구조가 근본적으로 달라지려는 세계혁명의 시작이다. 세계는 한 나라가 되어야 한다. 국가관이 달라져야 한다. 대국가주의시대大國家主義時代가 지나간다. 세계관이 달라지고 종교가 달라질 것이다. 아마 지금과는 딴판인 형태를 취할 것 아닐까? 종교의 근본 진리야 변할 리 없지만 모든 시대는 그 영원한 것의 새로운 표현을 요구한다. 각 시대는 제 말씀을 가진다. 장차 오는 시대의 말씀은 무엇이며, 누가 받을까? 새 종교개혁이 있기 위해 이번도 새 학문의 풍(風)이 일어나야 하지 않을까? 그러면 역시 과거의 새로운 해석이 있어야 할 것이다. 새로운 고전古典 연구가 필요하다.그 고전은 어떤 것일까? 서양 고전이 될 수는 없다. 그것은 이미 다 써먹었다. 그럼 동양 고전을 다시 음미하는 수밖에 없을 거다.막다른 골목에 든 서양문명을 건지는 길은 동양을 새로 맛보는 데서 나올 것이다.”

특히 종교 문제에 초점을 맞추었는데, 기성 종교는 국가주의와 너무 깊이 관련되었기에 낡은 문명과 함께 역사의 쓰레기통으로 들어갈 수밖에 없을 것이라고 했다. 마치 ‘종교 없는 그리스도교’를 말한 디트리히 본회퍼나 2000년 전 예수 탄생 때 동방에서 선물이 온 것처럼 지금도 ‘동방에서 새로운 정신적 선물이 와야 한다’고 한 토마스 머튼을 읽는 기분이다.

해방 후 사람들의 강권에 의해 임시자취원회 위원장이 되고, 이어서 평안북도 임시정부 교육부장의 책임을 맡기도 했다. 반공 시위인 신의주 학생시위의 배후로 지목되어 소련군 감옥에 두 번이나 투옥되었다. 밀정이 되기를 요구하는 소련군정에 더 이상 견딜 수가 없어 남한으로 넘어왔다. 1947년의 일이다.

월남하여서는 무교회 친구들의 협력으로 일요 종교 강좌를 열어 1960년까지 계속하면서 말로나 글로 자신의 생각을 펼쳤다. 젊은이들 사이에 그의 사상에 공명하는 사람들이 많이 생겼다. 필자도 「생각하는 백성이라야 산다」 등 그 당시 ��사상계思想界��에 실린 그의 글들을 읽었다. 그의 생각이 일반에게 알려지면서 한국 교회는 그를 이단으로 낙인찍고, 그의 무교회 친구들도 그를 멀리하기 시작했다. 세 가지 주된 이유는 그가 십자가를 부정하고, 기도하지 않고, 너무 동양적이라는 것이었다. 그러나 함석헌은 십자가를 부정하는 것이 아니라 ‘바라보는’ 십자가에서 ‘몸소 지는’ 십자가를 강조한 것이고, 기도도 ‘형식과 인간끼리의 아첨에 지나지 않는’ 공중기도를 삼갈 뿐이라고 하고, 동양 종교의 ‘깊은 뜻을 알지 못하고 그저 교파적인 좁은 생각’으로 동양적인 것을 배척하는 것에는 결코 동조할 수 없었다고 한다. 결국 표층 종교에 속한 사람들이 심층 종교로 들어가는 함석헌을 이해할 수 없었던 셈이다.

그러나 이런 일로 구태여 무교회와 결별할 생각은 없었다. 무교회를 떠난 결정적 계기는 ‘중대한 사건’ 때문이었다. 그가 오산 시절부터 간디를 알고 오래 동안 간디를 좋아해 간디 연구회를 만들 정도였는데, 동지들 사이에서 간디의 아슈람 비슷한 것을 만들자는 제안에 따라 1957년 천안에 ‘씨알농장’을 만들고 젊은 몇 사람과 같이 지내게 되었다. 이때 ‘도저히 변명할 수 없는 잘못’을 저질렀다. 형세는 돌변했다. 친구들이 모두 외면하고 떠나버린 것이다. 견딜 수 없이 외로웠다. 그러면서 관념적으로 믿고 있고 감정적으로 감격하던 십자가가 본인에게도 다른 사람에게도 아무 소용이 없음을 절감하게 되었다. 그는 그때의 심정을 다음과 같이 표현했다.

“십자가도 거짓말이러라

아미타불도 빈말이러라

“우리가 우리에게 죄지은 자를 사하여 준 것 같이 우리 죄를 사하여 주옵시고”도 공연한 말 뿐이러라

내가 쟝발장이되어 보자고 기를 바득바득 쓰건만 나타나는 건 미리엘이 아니고 쟈벨 뿐인 듯이 보이더라

무너진 내 탑은 이제 아까운 생각 없건만 저 언덕 높이 우뚝우뚝 서는 돌탑들이 저물어가는 햇빛을 가리워 무서운 생각만이 든다.”

이때를 예견한 것인가? 함석헌은 1947년 월남 이후 지은 그의 시 「그대 그런 사람을 가졌는가?」에서도 이와 비슷한 심정이 토로하고 있다.

“만리 길 나서는 길

처자를 내맡기며

맘놓고 갈만한 사람

그 사람을 그대는 가졌는가

온세상 다 나를 버려

마음이 외로울 때에도

‘저맘이야’하고 믿어지는

그 사람을 그대는 가졌는가

탔던 배 꺼지는 시간

救命袋 서로 사양하며

‘너만은 제발 살아다오’할

그 사람을 그대는 가졌는가

不義의 死刑場에서

‘다 죽여도 너희 세상 빛을 위해

저만은 살려 두거라’일러줄

그 사람을 그대는 가졌는가

잊지못 할 이 세상을 놓고 떠나려할 때

‘저 하나 있으니’하며

빙긋이 웃고 눈을 감을

그 사람을 그대는 가졌는가

온 세상의 찬성보다도

‘아니’하고 가만히 머리 흔들 그 한 얼굴 생각에

알뜰한 유혹을 물리치게 되는

그 사람을 그대는 가졌는가”

스승 류영모마저도 그를 공개적으로 질책하고 끝내 그를 내쳤다. 그러나 물론 그에 대한 사랑을 버린 것은 아니었다. ��다석일지��에 보면 “함은 이제 안 오려는가. 영 이별인가” 하며 탄식하는 등 7~8회에 걸쳐 제자 함석헌을 그리는 글이 나온다. 류영모는 “내게 두 벽이 있다. 동쪽 벽은 남강 이승훈 선생이고 서쪽 벽은 함석헌이다”고 할 정도였다.

심정적으로는 그럴지라도 겉으로는 스승으로부터도 버림받아 홀로 된 그에게 퀘이커가 나타났다. 퀘이커에 대해서는 오산 시절부터 들었지만 ‘좀 별난 사람들’이라는 정도로만 알고 있었는데, 한국 전쟁 후 구호사업으로 한국을 찾은 퀘이커들을 만나 처음으로 퀘이커 신도가 된 이윤구를 통해 퀘이커를 접하게 되었다. ‘갈 곳이 없는’ 상태에서 ‘물에 빠진 사람이 지푸라기라도 붙드는 심정으로’ 퀘이커 모임에 나갔다. 1961년 겨울이었다. 이렇게 되어 1962년 미국 펜실베이니아 주에 있는 퀘이커 훈련 센터인 펜들힐Pendle Hill에 가서 열 달 동안, 비슷한 성격의 영국 버밍엄에 있는 우드브루크Woodbrooke에 가서 석 달 동안 지내게 되었다. 이때까지만 해도 특별히 퀘이커가 될 생각은 없었다. ‘하룻밤 뽕나무 그늘 밑에서 자고 가려는 중의 심정’이었다. 그러다가 1967년 미국 북 캐롤라이나에서 열렸던 퀘이커 세계 대회에 퀘이커 친우들이 그를 대해 주는 데 어떤 책임감 같은 것을 느껴서 결국 퀘이커 정회원이 되었다. 그러면서도 그는 그의 심정을 다음과 같이 읊었다.

“그래도 나는 여전히 ‘수평선너머’를 내다봅니다.

내가 황햇가 모래밭에서 집을 지었다 헐면서 놀 때에 내다보던 수평선,

피난 때 낙동강 가에서 잔고기 한 쌍 기르다 죽이고 울면서 내다보던 수평선,

영원의 수평선너머를 나는 지금도 내다봅니다.”

함석헌은 류영모와 달리 현실참여에 적극적이었다. 1961년 장면 정권 때 국토 건설단에 초빙되어 5·16 군사 정권이 들어오기 전까지 정신교육 담당 강사로 활동하기도 했다. 1970년에는 잡지 ��씨의 소리��를 창간하여 그의 ‘씨 사상’을 널리 펼치고 동시에 군사정권에 반대하는 목소리를 대변하기도 했는데, 1980년 전두환 신군부 정권에 의해 폐간되었다가 1988년 8년 만에 복간되었다. 군사 정권에서는 군사 독재에 맞서서1974년 윤보선, 김대중 등과 함께 민주회복국민운동본부의 고문역을 맡아 시국선언에 동참하는 등 민주화 운동에 앞장서느라 여러 차례 옥고를 치렀다. 이런 민주화 운동을 인정받아 1979년과 1985년 두 차례에 걸쳐 미국 퀘이커 봉사회의 추천으로 노벨 평화상 후보자로 선정되기도 했다.

1989년 췌장암으로 서울대학교 병원에 입원, 2월 4일 새벽 5시 28분, 87년 11개월 가까이, 날짜로 33,105일을 사시고 세상을 떠났다. 함석헌을 따르며 그의 가르침을 받은 박재순 박사에 의하면, 돌아가시기 전 산소호흡기로 생명을 연장시키려 애쓰셨다는데, 그것이 스승 류영모가 돌아가신 날에 맞추려고 그런 것이 아니었던가 생각된다고 한다. 장례식은 조문객 2 명이 오산학교 강당에 모여 오산학교장으로 치르고 경기도 연천읍 간파리 마차산에 묻혔다가, 2002년 8월 15일 독립유공자자로 건국훈장이 추서되고, 이에 따라 대전 국립 현충원으로 이장되었다. 영원한 ‘들사람’에게는 약간 의외의 조치가 아닌가 여겨지는 면도 있다.

=====

그의 가르침

함석헌은 동서고금의 정신적 전통에서 낚아낸 깊은 사상을 바탕으로 일생을 통해 일관되게 생명, 평화, 민주,비폭력 등을 위해 힘쓴 ‘행동하는 신비주의자’, 세간에서 말하는 ‘한국의 간디’라 할 수 있다. 성경에 보면, “제자가 그 선생보다 높지 못하나 무릇 온전케 된 자는 그 선생과 같으리라”(누가복음6:40) 했다. ��도마복음��이나 ��장자��에도 비슷한 말이 있다. 류영모 선생님의 제자이지만, 어느 면에서 스승이 이루지 못한 부분을 보충했다는 의미에서 ‘청출어남이청어남靑出於藍而靑於藍’의 경우라 볼 수도 있지 않을까?

이제 함석헌의 사상이 어떻게 세계 종교의 심층, 곧 신비주의 전통과 통하는가, 그의 가르침이 어떻게 우리가 살펴본 인류의 정신적 스승들의 사상을 통섭하고 있는가, 몇 가지 예를 들어 간단히 살펴보기로 한다.

첫째는 경전을 ‘끊임없이 고쳐 해석해야’ 한다는 가르침이다

“경전의 생명은 그 정신에 있으므로 늘 끊임없이 고쳐 해석하여야 한다.…… 소위 정통주의라 하여 믿음의 살고 남은 껍질인 경전의 글귀를 그대로 지키려는 가엾은 것들은 사정없는 역사의 행진에 버림을 당할 것이다. 아니다, 역사가 버리는 것이 아니라 자기네가 스스로 역사를 버리는 것이다.”

종교적 진술을 문자적으로 이해하려는 ‘정통주의나 근본주의적’ 태도는 종교의 더욱 깊은 뜻을 이해하는 데 가장 큰 걸림돌이 된다. “성경을 문자적으로 읽으면 심각하게 받아들일 수 없고, 심각하게 받아들이려면 문자적으로 읽을 수 없다”고 한 신학자 폴 틸리히의 말이 생각나는 대목이다. 경전은 달을 가리키는 손가락과 같다. 그 자체로는 의미가 없는 것이다.

둘째는 ‘자라나는 신앙이 되게 하라’는 것이다.

“신앙은 생장기능生長機能을 가지고 있다. 이 생장은 육체적 생명에서도 그 특성의 하나이지만, 신앙에 있어서도 그러하다. 신앙에서 신앙으로 자라나 마침내 완전한 데 이르는 것이 산 신앙이다.”

“옛 전통을 자랑하는 교회는 낡아 빠진 종교다. 우리들만이 유일한 진리라고 말하는 종교는 낡아 빠진 종교이다. 신학적인 설명을 강요하기 휘해 과학을 원수처럼 생각하는 종교도 역시 낡아 빠진 종교다.”

자라지 않은 신앙은 죽은 신앙, 생명이 없는 신앙이다. 물로 세례를 받은 사람은 다시 바람(성령)으로 세례를 받고 결국에는 불로 세례를 받아야 한다는 『도마복음』의 주장과 일맥상통한다. 우리의 의식구조가 변화를 받아 점점 더 깊은 차원의 실재를 볼 수 있어야 한다는 뜻이다.

셋째는 ‘하나님은 내 마음 속에’라는 것이다.

“하나님은 다른 데선 만날 데가 없고, 우리 마음속에, 생각하는 데서만 만날 수가 있다.

자기를 존경함은 자기 안에 하나님을 믿음이다……그것이 자기발견이다.“

내 속에 있는 하나님이 바로 나의 가장 ‘본질적인 나’라는 뜻에서 내 속에 있는 하나님이 바로 나의 참 나라 할 수 있다. 내 속에 있는 하나님을 발견하는 것이 바로 나의 참 나를 발견하는 것이다. 이런 발견을 일반적으로 일컬어 ‘깨침’이라 한다. 심층 종교에서 말하는 가장 중요한 요소를 지적하고 있다.

넷째, ‘예수가 아니라 그리스도’이다.

“나는 역사적 예수를 믿는 것이 아니다. 믿는 것은 그리스도다. 그 그리스도는 영원한 그리스도가 아니면 안 된다. 그는 예수에게만 아니라 본질적으로는 내 속에도 있다. 그 그리스도를 통하여 예수와 나는 서로 다른 인격이 아니라 하나라는 체험에 들어갈 수 있다. 그때에 비로소 그의 죽음은 나의 육체의 죽음이요, 그의 부활은 내 영의 부활이 된다. 속죄는 이렇게 해서만 성립된다.”

놀라운 통찰이다.

예수는 자기 속에 있는 그리스도, 혹은 그리스도 의식Christ-consciousness임을 발견한 분이다.

우리도 우리 속에 있는 그리스도를 발견하면 예수와 같은 그리스도 의식에 동참하여 그와 일체감을 가질 수 있다.

1945년에 발견된 ��도마복음��을 비롯하여 심층 종교의 기본 가르침과 일치하는 것이다.

다섯째는 ‘사랑이 이긴다’는 가르침이다.

“평화주의가 이긴다.

인도주의가 이긴다.

사랑이 이긴다.

영원을 믿는 마음이 이긴다.”

지금까지 살펴본 것처럼, 세계 거의 모든 종교 신비주의 심층 전통에서는 나와 하느님이 하나임을 말함과 동시에 나와 다른 이들, 다른 사물들과도 결국 일체임을 깨닫는 것이 중요하다고 강조한다. 마이스터 에크하르트의 말이다. “어떤 경우가 천박한 이해인가? 나는 답하노라. ‘하나의 사물을 다른 것들과 분리된 것으로 볼 때’ 라고. 그리고 어떤 경우가 이런 천박한 이해를 넘어서는 것인가? 나는 말할 수 있노라. ‘모든 것이 모든 것 안에 있음을 깨닫고 천박한 이해를 넘어섰을 때’라고.”

여섯째는 ‘너와 나는 하나’라는 가르침이다.

“나는 나 혼자만 있는 것이 아니다. 남과 같이 있다. 그 남들과 관련 없이 나는 있을 수 없다. 그러므로 나와 남이 하나인 것을 믿어야 한다. 나·남이 떨어져 있는 한, 나는 어쩔 수 없는 상대적인 존재다. 그러므로 나·남이 없어져야 새로 난 ‘나’다. 그러므로 남이 없이, 그것이 곧 나다 하고 믿어야 한다.”

함석헌은 “내 속에 참 나가 있다”, “이 육체와 거기 붙은 모든 감각·감정은 내가 아니다”, “나의 참 나는 죽지도 않고, 늙지도 않고, 변하지도 않고 더러워지지도 않는다”고 하면서, 그러나 이것만으로는 부족하고 나와 만물이 하나임을 알아야 함을 강조하고 있다. 가히 사사무애事事無礙의 경지다.

일곱째는 ‘다름을 인정하라’는 것이다.

“우리의 생각이 좁아서는 안 되겠지요. 우주의 법칙, 생명의 법칙이 다원적이기 때문에 나와 달라도 하나로 되어야지요. 사람 얼굴도 똑같은 것은 없지 않아요? 생명이 본래 그런 건데, 종교와 사상에서만은 왜 나와 똑같아야 된다고 하느냐 말이야요. 생각이 좁아서 그렇지요. 다양한 생명이 자라나야겠는데……”

이사야나 아모스만이 하느님의 예언자가 아니라 동양의 공·맹, 노·장도 모두 다 하느님의 예언자다.

궁극적 실재가 인간의 이성으로 완전히 파악될 수 없다는 것을 알면 말이나 문자로 표현된 것의 절대적 타당성을 인정할 수 없다. 궁극 실재에 대한 우리 인간의 견해見解는 그 타당성이 결할 수밖에 없다. 모든 견해가 이럴 진데 나의 견해만 예외적으로 절대로 옳다고 주장할 수가 없다. 자연히 다원적 사고를 인정하게 된다.거의 모든 심층 종교, 신비주의 전통에서 한결같이 주장하는 바이다.

이런 몇 가지 예만으로도 함석헌의 사상이 류영모의 사상과 마찬가지로 세계 신비전통과 맥을 같이 한다는 것을 아는 데 충분하리라 생각한다. 특히 오늘 한국의 종교들이 거의 표층 종교 일색으로 변해 있는 상태에서 이들의 가르침이 얼마나 귀중한가 하는 것을 다시 마음에 새기게 된다. 들어가는 말에서 언급한 것처럼 독일 신학자 칼 라너Karl Rahner나 도로테 죌레Dorthee Soelle가 미래의 종교는 어쩔 수 없이 심층적인 종교, 신비주의적 종교일 수밖에 없다고 했을 때 류영모·함석헌의 사상에서 미래 종교의 광맥을 보는 듯하다 하면 과장일까?*

#함석헌 #오강남 #경계너머아하 #류영모

이제 함석헌의 사상이 어떻게 세계 종교의 심층, 곧 신비주의 전통과 통하는가, 그의 가르침이 어떻게 우리가 살펴본 인류의 정신적 스승들의 사상을 통섭하고 있는가, 몇 가지 예를 들어 간단히 살펴보기로 한다.

첫째는 경전을 ‘끊임없이 고쳐 해석해야’ 한다는 가르침이다

“경전의 생명은 그 정신에 있으므로 늘 끊임없이 고쳐 해석하여야 한다.…… 소위 정통주의라 하여 믿음의 살고 남은 껍질인 경전의 글귀를 그대로 지키려는 가엾은 것들은 사정없는 역사의 행진에 버림을 당할 것이다. 아니다, 역사가 버리는 것이 아니라 자기네가 스스로 역사를 버리는 것이다.”

종교적 진술을 문자적으로 이해하려는 ‘정통주의나 근본주의적’ 태도는 종교의 더욱 깊은 뜻을 이해하는 데 가장 큰 걸림돌이 된다. “성경을 문자적으로 읽으면 심각하게 받아들일 수 없고, 심각하게 받아들이려면 문자적으로 읽을 수 없다”고 한 신학자 폴 틸리히의 말이 생각나는 대목이다. 경전은 달을 가리키는 손가락과 같다. 그 자체로는 의미가 없는 것이다.

둘째는 ‘자라나는 신앙이 되게 하라’는 것이다.

“신앙은 생장기능生長機能을 가지고 있다. 이 생장은 육체적 생명에서도 그 특성의 하나이지만, 신앙에 있어서도 그러하다. 신앙에서 신앙으로 자라나 마침내 완전한 데 이르는 것이 산 신앙이다.”

“옛 전통을 자랑하는 교회는 낡아 빠진 종교다. 우리들만이 유일한 진리라고 말하는 종교는 낡아 빠진 종교이다. 신학적인 설명을 강요하기 휘해 과학을 원수처럼 생각하는 종교도 역시 낡아 빠진 종교다.”

자라지 않은 신앙은 죽은 신앙, 생명이 없는 신앙이다. 물로 세례를 받은 사람은 다시 바람(성령)으로 세례를 받고 결국에는 불로 세례를 받아야 한다는 『도마복음』의 주장과 일맥상통한다. 우리의 의식구조가 변화를 받아 점점 더 깊은 차원의 실재를 볼 수 있어야 한다는 뜻이다.

셋째는 ‘하나님은 내 마음 속에’라는 것이다.

“하나님은 다른 데선 만날 데가 없고, 우리 마음속에, 생각하는 데서만 만날 수가 있다.

자기를 존경함은 자기 안에 하나님을 믿음이다……그것이 자기발견이다.“

내 속에 있는 하나님이 바로 나의 가장 ‘본질적인 나’라는 뜻에서 내 속에 있는 하나님이 바로 나의 참 나라 할 수 있다. 내 속에 있는 하나님을 발견하는 것이 바로 나의 참 나를 발견하는 것이다. 이런 발견을 일반적으로 일컬어 ‘깨침’이라 한다. 심층 종교에서 말하는 가장 중요한 요소를 지적하고 있다.

넷째, ‘예수가 아니라 그리스도’이다.

“나는 역사적 예수를 믿는 것이 아니다. 믿는 것은 그리스도다. 그 그리스도는 영원한 그리스도가 아니면 안 된다. 그는 예수에게만 아니라 본질적으로는 내 속에도 있다. 그 그리스도를 통하여 예수와 나는 서로 다른 인격이 아니라 하나라는 체험에 들어갈 수 있다. 그때에 비로소 그의 죽음은 나의 육체의 죽음이요, 그의 부활은 내 영의 부활이 된다. 속죄는 이렇게 해서만 성립된다.”

놀라운 통찰이다.

예수는 자기 속에 있는 그리스도, 혹은 그리스도 의식Christ-consciousness임을 발견한 분이다.

우리도 우리 속에 있는 그리스도를 발견하면 예수와 같은 그리스도 의식에 동참하여 그와 일체감을 가질 수 있다.

1945년에 발견된 ��도마복음��을 비롯하여 심층 종교의 기본 가르침과 일치하는 것이다.

다섯째는 ‘사랑이 이긴다’는 가르침이다.

“평화주의가 이긴다.

인도주의가 이긴다.

사랑이 이긴다.

영원을 믿는 마음이 이긴다.”

지금까지 살펴본 것처럼, 세계 거의 모든 종교 신비주의 심층 전통에서는 나와 하느님이 하나임을 말함과 동시에 나와 다른 이들, 다른 사물들과도 결국 일체임을 깨닫는 것이 중요하다고 강조한다. 마이스터 에크하르트의 말이다. “어떤 경우가 천박한 이해인가? 나는 답하노라. ‘하나의 사물을 다른 것들과 분리된 것으로 볼 때’ 라고. 그리고 어떤 경우가 이런 천박한 이해를 넘어서는 것인가? 나는 말할 수 있노라. ‘모든 것이 모든 것 안에 있음을 깨닫고 천박한 이해를 넘어섰을 때’라고.”

여섯째는 ‘너와 나는 하나’라는 가르침이다.

“나는 나 혼자만 있는 것이 아니다. 남과 같이 있다. 그 남들과 관련 없이 나는 있을 수 없다. 그러므로 나와 남이 하나인 것을 믿어야 한다. 나·남이 떨어져 있는 한, 나는 어쩔 수 없는 상대적인 존재다. 그러므로 나·남이 없어져야 새로 난 ‘나’다. 그러므로 남이 없이, 그것이 곧 나다 하고 믿어야 한다.”

함석헌은 “내 속에 참 나가 있다”, “이 육체와 거기 붙은 모든 감각·감정은 내가 아니다”, “나의 참 나는 죽지도 않고, 늙지도 않고, 변하지도 않고 더러워지지도 않는다”고 하면서, 그러나 이것만으로는 부족하고 나와 만물이 하나임을 알아야 함을 강조하고 있다. 가히 사사무애事事無礙의 경지다.

일곱째는 ‘다름을 인정하라’는 것이다.

“우리의 생각이 좁아서는 안 되겠지요. 우주의 법칙, 생명의 법칙이 다원적이기 때문에 나와 달라도 하나로 되어야지요. 사람 얼굴도 똑같은 것은 없지 않아요? 생명이 본래 그런 건데, 종교와 사상에서만은 왜 나와 똑같아야 된다고 하느냐 말이야요. 생각이 좁아서 그렇지요. 다양한 생명이 자라나야겠는데……”

이사야나 아모스만이 하느님의 예언자가 아니라 동양의 공·맹, 노·장도 모두 다 하느님의 예언자다.

궁극적 실재가 인간의 이성으로 완전히 파악될 수 없다는 것을 알면 말이나 문자로 표현된 것의 절대적 타당성을 인정할 수 없다. 궁극 실재에 대한 우리 인간의 견해見解는 그 타당성이 결할 수밖에 없다. 모든 견해가 이럴 진데 나의 견해만 예외적으로 절대로 옳다고 주장할 수가 없다. 자연히 다원적 사고를 인정하게 된다.거의 모든 심층 종교, 신비주의 전통에서 한결같이 주장하는 바이다.

이런 몇 가지 예만으로도 함석헌의 사상이 류영모의 사상과 마찬가지로 세계 신비전통과 맥을 같이 한다는 것을 아는 데 충분하리라 생각한다. 특히 오늘 한국의 종교들이 거의 표층 종교 일색으로 변해 있는 상태에서 이들의 가르침이 얼마나 귀중한가 하는 것을 다시 마음에 새기게 된다. 들어가는 말에서 언급한 것처럼 독일 신학자 칼 라너Karl Rahner나 도로테 죌레Dorthee Soelle가 미래의 종교는 어쩔 수 없이 심층적인 종교, 신비주의적 종교일 수밖에 없다고 했을 때 류영모·함석헌의 사상에서 미래 종교의 광맥을 보는 듯하다 하면 과장일까?*

#함석헌 #오강남 #경계너머아하 #류영모