Quakers & Capitalism—The Book | Through the Flaming Sword

Quakers & Capitalism—The Book

This page features links to sections I’ve already written of my book on Quakers and Capitalism by that title. Note that since this is still a work in progress, there are notes here and there about content that still needs to be developed. In some of these areas, I have the research but haven’t done the writing yet. In others, I am hoping that some of my readers will be able to contribute. These notes appear in brackets.

Quakers and Capitalism

Introduction

The 1650s: The Lamb’s War and the Social Order

Transition (1661-1695): Persecution & Gospel Order

The Double-culture Period (1695-1895): The Double-Culture Period

Evangelicalism and Political Economy (the 1800s)

Second Transition (1895-1920): The Corporation, the Great War, Liberalism and the Social Order

Appendices

Quaker Contributions to Industrial Capitalism—A Summary

Foundations of a True Social Order

Seebohm Rowntree – A bibliography

Share this:

Press This

§ 12 Responses to Quakers & Capitalism—The Book

November 29, 2014 at 2:41 pm

Have you read Frederick Tolles “Meeting House and Counting House”? Another source is a book published decades ago by the Harvard Business School on Isaac Hicks, a NYC merchant who gave up a thriving business to travel as a companion to Elias Hicks.

Marge Abbott

Reply

November 30, 2014 at 10:30 am

Thank you, Marge. Yes I have read Meeting House and Counting House, but not the book about Hicks. Sounds interesting.

Reply

January 3, 2012 at 8:03 pm

Hi Stephen,

Happy New Year!

I’ve been fascinated by your blog and it has prompted me to do a whole bunch of self-challenging and self-education.

So, the obvious I”m wondering when you are going to publish your book?

I am very interested in working with others to develop practical guides and resources for businesses. Is this something you are interested in, or do you know of others who share this interest?

Regards

Stephen

Reply

January 6, 2012 at 1:54 pm

Hi, Stephen

Sorry it’s taken me a while to respond. I’m glad you find my blog useful. As for when I might publish, I don’t really know. I haven’t done much research on the history of Quaker economics in the 20th century and that could take a while. That is one of the reasons I started the blog, to get some of this material out there without having to wait until it was all ready. What I would really like is to find collaborators who have already done this research and include them as co-authors.

I am somewhat interested in practical business guides, though bigger picture macroeconomic issues interest me more. One little bit that I haven’t done with the research I’ve done so far is a more thorough treatment of Quaker innovations in business practice and labor relations during the 18th and 19th centuries. There’s quite a bit of material available, and I’ve even read most of it, but either didn’t take good notes or haven’t yet got to them. Also, George Fox wrote a rather detailed epistle to business people about their practice quite early on; I have the reference somewhere, but would have to did to find it.

There are some good and more contemporary pamphlets on business practice, which I’ve skimmed. And I’ve been communicating with a Friend who is very knowledgeable and personally active in labor relations. She is the person who could probably work with you most closely. Her name is Linda Lotz and her email address is llotz@hotmail.com. I think Linda is right that labor relations deserve more attention in our testimonies’ evolution and they would be a big part of a more enlightened testimony on business practice.

Well, I’ve hinted at a lot and not given you much that is substantive. Let’s keep corresponding and I’ll gather some resource references I think you might find useful.

And thanks again for reading and contacting me.

Steve

Reply

January 8, 2012 at 12:10 am

Hi Steven,

Thanks for your comments and your generosity with information! I will follow through and keep you posted.

I could possibly help as an ‘assistant researcher’ or ‘second head’ on Quaker economics in the 20th century if that is of help. I’m a member of Quakers and Business (http://qandb.org/) and perhaps people there would be of help too?

Don’t worry about Foxe’s comments – I’ve found the most succinct are in letter 200 (e.g. see http://www.hallvworthington.com/Letters/gfsection9.html). And thanks for the referral to Linda.

My thinking at this stage is to focus on a guide and to that extent avoid overlapping with your work. This points to a focus on recent developments among Quakers and also those aligned with Quaker practice.

In the first instance, I will take a leaf from your book and start using a blog to map out ideas etc.

So once again, thanks for your initiative and energy with such a major task – and my best wishes (and possible help if needed) for the future!

Stephen

November 4, 2012 at 9:11 pm

Stephen,

I’m a business professor at a small Appalachian university and might be interested in working a bit with you and exchanging ideas with you. Friends in the family for quite awhile, though we usually managed to get kicked out of meeting fairly regularly.

I would suggest looking to two early 20th century sources from the US.

First, Fredrick Taylor who was from a Quaker family – though I think adopted. Here you would have to go to the original sources as “Taylor ism” has less than a good name, but the thoughts and indications are clear…..Indeed, there is a direct line from this work to the sustainable economics writers such as Porter from Harvard who are developing value-chain and community models of business.

Another who you should not ignore is Hoover and his work in disaster relief, and policy changes. Again, a bad name so the orig. would serve you better than the historical revision.

For a general history of the NC Friends in the older days, Stephen Weeks = (also, adopted) is a reliable mid-century source for the period when Friends predominated in NC politics, and shortly thereafter. His work is probably available online. There is an excellent History professor at UT Chattanooga who probably has some interesting source material as well. I’m away from my research material so I can’t provide his name, but he did a quite readable history of Fox a few decades ago now.

Also, of course, the Chase family. There is an odd connection to duPont as well, but it is not direct and I’ve never run it down as to where their early management influences came from.

/ernie

Reply

November 6, 2012 at 4:56 pm

Hi, Ernie

I know you responded to Stephen (at least I think so; because we sort of have the same name, there’s room for confusion), but I am grateful for your comments. I had forgotten that Taylor was a Friend, and I imagine that both he and Hoover (they knew each other didn’t they?) come from the same technocratic emergence within Progressivism.

I would dearly like to add material about both to my book. My problem is time. I’ve already spent years on this book and I’m already 65. I don’t suppose you would be interested in contributing would you? My solution to the time problem is to invite others to collaborate on bringing the work up through the 20th century.

Steven Davison

November 14, 2012 at 11:55 pm

Hi Ernie and Steven,

Thanks for the referrals – I’m happy to scope stuff and pass it through to you, Steven, if this helps?

I’ll be a month or so as I’m completely snowed under at present – and will let you know when I’ve something to share.

And thanks again!

Stephen

August 24, 2011 at 9:17 pm

I really enjoyed what you wrote so far. However, I did kind of lose it when you wrote about the spirit of capitalism. I don’t know if you read the World is Flat by Thomas Friedman. I could swear that he credited Quakers with helping to open up the New World for trading based on the close connections that the Quakers had. But when I have gone back and tried to find the passage to quote it, I can’t find it. It does fit with what you have written.

Reply

August 25, 2011 at 8:28 am

Thanks for your comment, Karen. I’m glad you’re enjoying my work so far.

I did skimp on the development of Max Weber’s ideas in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism as they relate to Friends and their economic history. He wrote a whole book on the topic and referred often to Quakers to illustrate his argument, and I condensed the whole thing down to a few paragraphs. I feel the subject deserves more attention and maybe I’ll return to it with more effort in the future. In the meantime, I’ll review what I have written and see if I can make it clearer and more compelling. Thanks for the feedback.

As for Quakers and New World trade, this is another area that I’ve not studied yet in depth, but I would not be surprised if your memory of Friedman is correct. Penn’s colony was settled quite early in our history and once it was granted by the king in the 1680s—still quite early—the connections with the mother country quickly became the best in the colonies. And the Quaker transatlantic network was extremely valuable. Most other shipping ventures took a 30% loss for granted: theft, damage, graft, piracy, and of course, shipwreck, all took their toll. But, between Friends, many of these problems were minimized and the reliable profitability of trade helped make Friends rich while creating one of the earliest and biggest and most efficient pipelines for goods and money between England and America.

I think I touch on this in one of my posts, but like everything else, there’s a lot more to say.

Thanks again for your interest.

Reply

January 22, 2011 at 10:46 pm

Dear Stephen,

I happened to notice your blog on a Facebook posting and am thrilled to find it. Just read the introduction and first chapter of your proposed book, and I’m appreciating so much what you’re laying out. You’re addressing questions I’ve had since becoming a Quaker, as well as some of my inner longing as a Friend to be more connected with economic justice activists who challenge and critically analyze contemporary capitalism.

I don’t have the time to read a lot or to engage with others around all this much right now, but I’m so glad you’re writing this. Perhaps later this spring I will organize a short term study group at my meeting to read what you’ve written.

In Friendship,

Paulette Meier

Reply

January 23, 2011 at 9:06 am

Thanks, Paulette. Stay tuned. There’s more to come, albeit slowly.

Steven

Reply

David William McKay

David William McKay

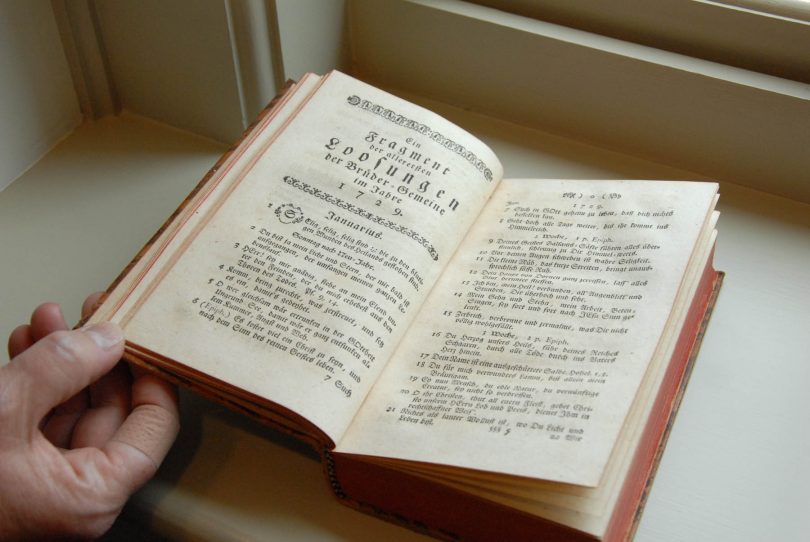

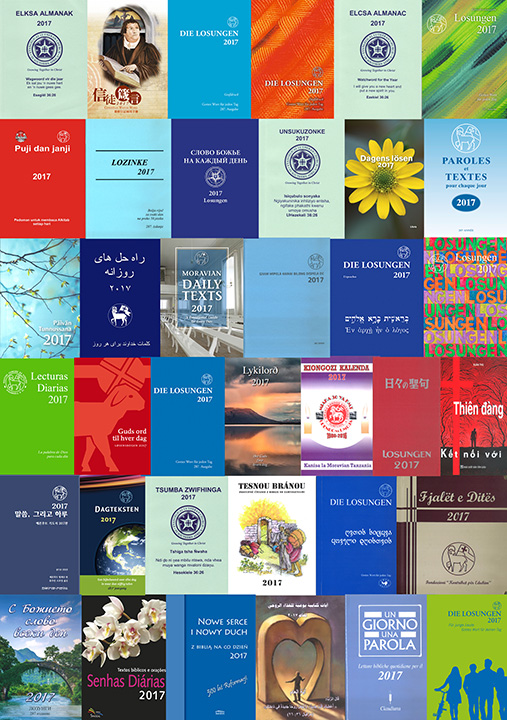

62 languages and countingToday, the Moravian Daily Texts appear in 62 languages worldwide. In 2017, three new languages were added to the large number of editions of the Moravian Daily Texts: Syriac Aramaic, Tok Pisin (a language spoken in Papua New Guinea) and Vietnamese.Local church groups, often working with partners in Germany, took the initiative to translate, publish and distribute their version of the Moravian Daily Texts. All three projects received a start-up grant from the Moravian Church in Germany. The Vietnamese Daily Text book is published in two biannual installments. The Daily Texts from Papua New Guinea are printed in a print-run of 500 copies under the title: “Givim Mipela Kaikai Bilong Dispela De” (Give Us Today Our Daily Bread). The Syriac Aramaic version is still in translation.

62 languages and countingToday, the Moravian Daily Texts appear in 62 languages worldwide. In 2017, three new languages were added to the large number of editions of the Moravian Daily Texts: Syriac Aramaic, Tok Pisin (a language spoken in Papua New Guinea) and Vietnamese.Local church groups, often working with partners in Germany, took the initiative to translate, publish and distribute their version of the Moravian Daily Texts. All three projects received a start-up grant from the Moravian Church in Germany. The Vietnamese Daily Text book is published in two biannual installments. The Daily Texts from Papua New Guinea are printed in a print-run of 500 copies under the title: “Givim Mipela Kaikai Bilong Dispela De” (Give Us Today Our Daily Bread). The Syriac Aramaic version is still in translation.