Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life.[1][2][3]

Background[edit source]

Pilgrimages frequently involve a journey or search of moral or spiritual significance. Typically, it is a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person's beliefs and faith, although sometimes it can be a metaphorical journey into someone's own beliefs.

Many religions attach spiritual importance to particular places: the place of birth or death of founders or saints, or to the place of their "calling" or spiritual awakening, or of their connection (visual or verbal) with the divine, to locations where miracles were performed or witnessed, or locations where a deity is said to live or be "housed", or any site that is seen to have special spiritual powers. Such sites may be commemorated with shrines or temples that devotees are encouraged to visit for their own spiritual benefit: to be healed or have questions answered or to achieve some other spiritual benefit.

A person who makes such a journey is called a pilgrim. As a common human experience, pilgrimage has been proposed as a Jungian archetype by Wallace Clift and Jean Dalby Clift.[4]

The Holy Land acts as a focal point for the pilgrimages of the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. According to a Stockholm University study in 2011, these pilgrims visit the Holy Land to touch and see physical manifestations of their faith, confirm their beliefs in the holy context with collective excitation, and connect personally to the Holy Land.[5]

The Christian priest Frank Fahey writes that a pilgrim is "always in danger of becoming a tourist", and vice versa since travel always in his view upsets the fixed order of life at home, and identifies eight differences between the two:[6]

| Element | Pilgrimage | Tourism |

|---|---|---|

| Faith | always contains "faith expectancy" | not required |

| Penance | search for wholeness | not required |

| Community | often solitary, but should be open to all | often with friends and family, or a chosen interest group |

| Sacred space | silence to create an internal sacred space | not present |

| Ritual | externalizes the change within | not present |

| Votive offering | leaving behind a part of oneself, letting go, in search of a better life | not present; the travel is the good life |

| Celebration | "victory over self", celebrating to remember | drinking to forget |

| Perseverance | commitment; "pilgrimage is never over" | holidays soon end |

Bahá'í Faith[edit source]

Bahá'u'lláh decreed pilgrimage to two places in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas: the House of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdad, Iraq, and the House of the Báb in Shiraz, Iran. Later, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá designated the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh at Bahji, Israel as a site of pilgrimage.[7] The designated sites for pilgrimage are currently not accessible to the majority of Bahá'ís, as they are in Iraq and Iran respectively, and thus when Bahá'ís currently refer to pilgrimage, it refers to a nine-day pilgrimage which consists of visiting the holy places at the Bahá'í World Centre in northwest Israel in Haifa, Acre, and Bahjí.[7]

Buddhism[edit source]

There are four places that Buddhists pilgrimage to:

- Lumbini: Buddha's birthplace (in Nepal)

- Bodh Gaya: place of Enlightenment (in the current Mahabodhi Temple, Bihar, India)

- Sarnath: (formally Isipathana, Uttar pradesh, India) where he delivered his first sermon (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta), and the Buddha taught about the Middle Way, the Four Noble Truths and Noble Eightfold Path.

- Kusinara: (now Kusinagar, India) where he attained mahaparinirvana (died).

Other pilgrimage places in India and Nepal connected to the life of Gautama Buddha are: Savatthi, Pataliputta, Nalanda, Gaya, Vesali, Sankasia, Kapilavastu, Kosambi, Rajagaha.

Other famous places for Buddhist pilgrimage include:

- India: Sanchi, Ellora Caves, Ajanta Caves, also see Buddhist pilgrimage sites in India

- Thailand: Wat Phra Kaew, Wat Pho, Wat Doi Suthep, Phra Pathom Chedi, Sukhothai, Ayutthaya

- Tibet: Lhasa (traditional home of the Dalai Lama), Mount Kailash, Lake Nam-tso

- Cambodia: Wat Botum, Wat Ounalom, Wat Botum, Silver Pagoda, Angkor Wat

- Sri Lanka: Temple of the Tooth, Polonnaruwa, (Kandy), Anuradhapura

- Laos: Luang Prabang

- Malaysia: Kek Lok Si, Buddhist Maha Vihara, Brickfields

- Myanmar: Shwedagon Pagoda, Mahamuni Buddha Temple, Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, Bagan, Sagaing Hill, Mandalay Hill,

- Nepal: Maya Devi Temple, Boudhanath, Swayambhunath

- Indonesia: Borobudur, Mendut, Sewu

- China: Yung-kang, Lung-men caves. The Four Sacred Mountains

- Japan:

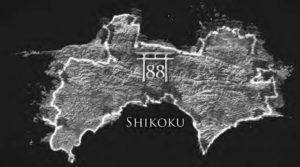

- Shikoku Pilgrimage, 88 Temple pilgrimage in the Shikoku island.

- Japan 100 Kannon Pilgrimage, pilgrimage composed of the Saigoku, Bandō and Chichibu pilgrimages.

- Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage, pilgrimage in the Kansai region.

- Bandō Sanjūsankasho, pilgrimage in the Kantō region.

- Chichibu 34 Kannon Sanctuary, pilgrimage in Saitama Prefecture.

- Chūgoku 33 Kannon Pilgrimage, pilgrimage in the Chūgoku region.

- Kumano Kodō

- Mount Kōya.

Christianity[edit source]

Christian pilgrimage was first made to sites connected with the birth, life, crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. Aside from the early example of Origen in the third century, surviving descriptions of Christian pilgrimages to the Holy Land date from the 4th century, when pilgrimage was encouraged by church fathers including Saint Jerome, and established by Saint Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great.[8]

The purpose of Christian pilgrimage was summarized by Pope Benedict XVI in this way:

Pilgrimages were, and are, also made to Rome and other sites associated with the apostles, saints and Christian martyrs, as well as to places where there have been apparitions of the Virgin Mary. A popular pilgrimage journey is along the Way of St. James to the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral, in Galicia, Spain, where the shrine of the apostle James is located. A combined pilgrimage was held every seven years in the three nearby towns of Maastricht, Aachen and Kornelimünster where many important relics could be seen (see: Pilgrimage of the Relics, Maastricht). Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales recounts tales told by Christian pilgrims on their way to Canterbury Cathedral and the shrine of Thomas Becket. Marian pilgrimages remain very popular in Latin America.

Hinduism[edit source]

According to Karel Werner's Popular Dictionary of Hinduism, "most Hindu places of pilgrimage are associated with legendary events from the lives of various gods.... Almost any place can become a focus for pilgrimage, but in most cases they are sacred cities, rivers, lakes, and mountains."[10] Hindus are encouraged to undertake pilgrimages during their lifetime, though this practice is not considered absolutely mandatory. Most Hindus visit sites within their region or locale.

- Kumbh Mela: Kumbh Mela is one of the largest gatherings of humans in the world where pilgrims gather to bathe in a sacred or holy river.[11][12][13] The location is rotated among Allahabad, Haridwar, Nashik, and Ujjain.

- Char Dham (Four Holy pilgrimage sites): The famous four holy sites Puri, Rameswaram, Dwarka, and Badrinath (or alternatively the Himalayan towns of Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, and Yamunotri) compose the Char Dham (four abodes) pilgrimage circuit.

- Kanwar Pilgrimage: The Kanwar is India's largest annual religious pilgrimage. As part of this phenomenon, millions of participants gather sacred water from the Ganga (usually in Haridwar, Gangotri, Gaumukh, or Sultanganj) and carry it across hundreds of miles to dispense as offerings in Śiva shrines.[14]

- Old Holy cities per Puranic Texts: Varanasi also known as Kashi (Shiva), Allahabad also known as Prayag, Haridwar-Rishikesh (Vishnu), Mathura-Vrindavan (Krishna), Pandharpur (Krishna), Paithan, Kanchipuram (Parvati), Dwarka (Krishna) and Ayodhya (Rama).

- Major Temple cities: Puri, which hosts a major Vaishnava Jagannath temple and Rath Yatra celebration; Katra, home to the Vaishno Devi Temple; Three comparatively recent temples of fame and huge pilgrimage are Shirdi, home to Sai Baba of Shirdi, Tirumala - Tirupati, home to the Tirumala Venkateswara Temple; and Sabarimala, where Swami Ayyappan is worshipped.

- Shakti Peethas: Another important set of pilgrimages are the Shakti Peethas, where the Mother Goddess is worshipped, the two principal ones being Kalighat and Kamakhya.

- Pancha Ishwarams - the five ancient Shiva temples of the island from classical antiquity.

- The Murugan pilgrimage route of Sri Lanka, an ancient Arunagirinathar-traversed Pada Yatra route of Tiruppadai temples includes the Maviddapuram Kandaswamy Temple in Kankesanturai, the Nallur Kandaswamy temple in Jaffna, the Pancha Ishwaram Koneswaram temple in Trincomalee, the Verugal Murugan Kovil on the banks of the river Verugal Aru, in Verugal, Trincomalee District, the Mandur Kandaswamy temple of Mandur (Sri Lanka), Thirukkovil Sithira Velayutha Swami Kovil, in Thirukkovil, Batticaloa, the Arugam Bay and Panamai in Amparai district, the Ukanthamalai Murugan Kovil, in Okanda, Kumana National Park and then through the park and Tissamaharama to the deity's holiest site, Kataragama temple, Katirkamam in the South.

Islam[edit source]

The Ḥajj (Arabic: حَـجّ, main pilgrimage to Mecca) is one of the five pillars of Islam and a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried out at least once in their lifetime by all adult Muslims who are physically and financially capable of undertaking the journey, and can support their family during their absence.[15][16][17] The gathering during the Hajj is considered the largest annual gathering of people in the world.[18][19][20] Since 2014, two or three million people have participated the Hajj annually.[21] The mosques in Mecca and Medina were closed in February 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the hajj was permitted for only a very limited number of Saudi nationals and foreigners living in Saudi Arabia starting on 29 July.[22]

Another important place for Muslims is the city of Medina, the second holiest site in Islam, in Saudi Arabia, the final resting place of Muhammad in Al-Masjid an-Nabawi (The Mosque of the Prophet).[23]

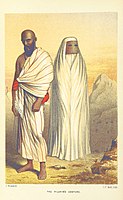

The Ihram (white robe of pilgrimage) is meant to show equality of all Muslim pilgrims in the eyes of Allah. 'A white has no superiority over a black, nor a black over a white. Nor does an Arab have superiority over a non-Arab, nor a non-Arab over an Arab - except through piety' - statement of the Prophet Muhammad.

About four million pilgrims participate in the Grand Magal of Touba, 200 kilometres (120 mi) east of Dakar, Senegal. The pilgrimage celebrates the life and teachings of Cheikh Amadou Bamba, who founded the Mouride brotherhood in 1883 and begins on the 18th of Safar.[24]

Shia[edit source]

Al-Arba‘īn (Arabic: ٱلْأَرْبَـعِـيْـن, "The Forty"), Chehelom (Persian: چهلم, Urdu: چہلم, "the fortieth [day]") or Qirkhī, Imāmīn Qirkhī (Azerbaijani: İmamın qırxı (Arabic: إمامین قیرخی), "the fortieth of Imam") is a Shia Muslim religious observance that occurs forty days after the Day of Ashura. It commemorates the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of Muhammad, which falls on the 20th or 21st day of the month of Safar. Imam Husayn ibn Ali and 72 companions were killed by Yazid I's army in the Battle of Karbala in 61 AH (680 CE). Arba'een or forty days is also the usual length of mourning after the death of a family member or loved one in many Muslim traditions. Arba'een is one of the largest pilgrimage gatherings on Earth, in which up to 31 million people go to the city of Karbala in Iraq.[25][26][27][28]

The second largest holy city in the world, Mashhad, Iran, attracts more than 20 million tourists and pilgrims every year, many of whom come to pay homage to Imam Reza (the eighth Shi'ite Imam). It has been a magnet for travelers since medieval times.[29] Due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran, worshippers were encouraged to stay at home rather than visit the cities of Najaf and Karbala. Smaller than usual crowds gathered for Ashura, but many did not wear facemasks or practice social distancing, and the number of cases of viral infections in Iran grew sharply.[21]

Judaism[edit source]

While Solomon's Temple stood, Jerusalem was the centre of the Jewish religious life and the site of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals of Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot, and all adult men who were able were required to visit and offer sacrifices (korbanot) at the Temple. After the destruction of the Temple, the obligation to visit Jerusalem and to make sacrifices no longer applied. The obligation was restored with the rebuilding of the Temple, but following its destruction in 70 CE, the obligation to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and offer sacrifices again went into abeyance.[30]

The western retaining wall of the Temple Mount, known as the Western Wall or "Wailing" Wall, is the remaining part of Second Jewish Temple in the Old City of Jerusalem is the most sacred and visited site for Jews. Pilgrimage to this area was off-limits to Jews from 1948 to 1967, when East Jerusalem was under Jordanian control.[31][32]

There are numerous lesser Jewish pilgrimage destinations, mainly tombs of tzadikim, throughout the Land of Israel and all over the world, including: Hebron; Bethlehem; Mount Meron; Netivot; Uman, Ukraine; Silistra, Bulgaria; Damanhur, Egypt; and many others.[33]

Sikhism[edit source]

Sikhism does not consider pilgrimage as an act of spiritual merit. Guru Nanak went to places of pilgrimage to reclaim the fallen people, who had turned ritualists. He told them of the need to visit that temple of God, deep in the inner being of themselves. According to him: "He performs a pilgrimage who controls the five vices."[34][35]

Eventually, however, Amritsar and Harmandir Sahib (the Golden Temple) became the spiritual and cultural centre of the Sikh faith, and if a Sikh goes on pilgrimage it is usually to this place.[36]

The Panj Takht (Punjabi: ਪੰਜ ਤਖ਼ਤ) are the five revered gurdwaras in India that are considered the thrones or seats of authority of Sikhism and are traditionally considered a pilgrimage.[37]

Taoism[edit source]

Mazu, also spelled as Matsu, is the most famous sea goddess in the Chinese southeastern sea area, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Mazu Pilgrimage is more likely as an event (or temple fair), pilgrims are called as "Xiang Deng Jiao" (pinyin: xiāng dēng jiǎo, it means "lantern feet" in Chinese), they would follow the Goddess's (Mazu) palanquin from her own temple to another Mazu temple. By tradition, when the village Mazu palanquin passes, the residents would offer free water and food to those pilgrims along the way.

There are 2 main Mazu pilgrimages in Taiwan, it usually hold between lunar January and April, depends on Mazu's will.

- Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage: this pilgrimage can be traced to 1863, from Baishantun (Miaoli County) to Beigang (Yunlin County) and return, not over a definite route.[38]

- Dajia Mazu Pilgrimage: from Dajia (Taichung City) to Xingang (Chiayi County) and return, it runs over a definite route.[39]

Zoroastrianism[edit source]

In Iran, there are pilgrimage destinations called pirs in several provinces, although the most familiar ones are in the province of Yazd.[40] In addition to the traditional Yazdi shrines, new sites may be in the process of becoming pilgrimage destinations. The ruins are the ruins of ancient fire temples. One such site is the ruin of the Sassanian era Azargoshnasp fire temple in Iran's Azarbaijan Province. Other sites are the ruins of fire temples at Rey, south of the capital Tehran, and the Firouzabad ruins sixty kilometres south of Shiraz in the province of Pars.

Atash Behram ("Fire of victory") is the highest grade of fire temple in Zoroastrianism. It has 16 different "kinds of fire", that is, fires gathered from 16 different sources.[41] Currently there are 9 Atash Behram, one in Yazd, Iran and the rest in Western India. They have become a pilgrimage destination.[42]

In India the cathedral fire temple that houses the Iranshah Atash Behram, located in the small town of Udvada in the west coast province of Gujarat, is a pilgrimage destination.[42]

Other[edit source]

Meher Baba[edit source]

The main pilgrimage sites associated with the spiritual teacher Meher Baba are Meherabad, India, where Baba completed the "major portion"[43] of his work and where his tomb is now located, and Meherazad, India, where Baba resided later in his life.

Ancient Greece[edit source]

The Eleusinian mysteries included a pilgrimage. The procession to Eleusis began at the Athenian cemetery Kerameikos and from there the participants walked to Eleusis, along the Sacred Way (Ἱερὰ Ὁδός, Hierá Hodós).[44]

See also[edit source]

- Burial places of founders of world religions

- HCPT – The Pilgrimage Trust

- Hiking

- Journey of self-discovery

- Junrei

- List of shrines

- List of significant religious sites

- Monastery

- New Age travellers

- Pardon (ceremony)

- Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia § Pilgrimages

- Romeria

- Sacred travel

- World Youth Day

References[edit source]

- ^ Reader, Ian; Walter, Tony, eds. (2014). Pilgrimage in popular culture. [Place of publication not identified]: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1349126392. OCLC 935188979.

- ^ Reframing pilgrimage : cultures in motion. Coleman, Simon, 1963-, Eade, John, 1946-, European Association of Social Anthropologists. London: Routledge. 2004. ISBN 9780203643693. OCLC 56559960.

- ^ Plate, S. Brent (September 2009). "The Varieties of Contemporary Pilgrimage". CrossCurrents. 59 (3): 260–267. doi:10.1111/j.1939-3881.2009.00078.x.

- ^ Cleft, Jean Darby; Cleft, Wallace (1996). The Archetype of Pilgrimage: Outer Action With Inner Meaning. The Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-3599-X.

- ^ Metti, Michael Sebastian (1 June 2011). "Jerusalem – the most powerful brand in history" (PDF). Stockholm University School of Business. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ a b Fahey, Frank (April 2002). "Pilgrims or Tourists?". The Furrow. 53 (4): 213–218. JSTOR 27664505.

- ^ a b Smith, Peter (2000). "Pilgrimage". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: eworld Publications. pp. 269. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ Cain, A. (2010). Jerome's epitaphium paulae: Hagiography, pilgrimage, and the cult of Saint Paula. Journal of Early Christian Studies, 18(1), 105-139. https://doi.org/10.1353/earl.0.0310

- ^ "Apostolic Journey to Santiago de Compostela and Barcelona: Visit to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (November 6, 2010) | BENEDICT XVI".

- ^ Werner, Karel (1994). A popular dictionary of Hinduism. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 0700702792. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ Thangham, Chris V. (3 January 2007). "Photo from Space of the Largest Human Gathering in India". Digital Journal. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Banerjee, Biswajeet (15 January 2007). "Millions of Hindus Wash Away Their Sins". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ "Millions bathe at Hindu festival". BBC News. 3 January 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Singh, Vikas (2017). Uprising of the Fools: Pilgrimage as Moral Protest in Contemporary India. Stanford University Press.

- ^ Long, Matthew (2011). Islamic Beliefs, Practices, and Cultures. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-7614-7926-0. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-253-21627-3.

- ^ "Islamic Practices". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ Mosher, Lucinda (2005). Praying: The Rituals of Faith. Church Publishing, Inc. p. 155. ISBN 9781596270169. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Ruiz, Enrique (2009). Discriminate Or Diversify. PositivePsyche.Biz Corp. p. 279. ISBN 9780578017341.

- ^ Katz, Andrew (16 October 2013). "As the Hajj Unfolds in Saudi Arabia, A Deep Look Inside the Battle Against MERS". Time. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ a b "The world's largest Muslim pilgrimage site? Not Mecca, but the Shiite shrine in Karbala". Religion News Service. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Hajj Begins in Saudi Arabia Under Historic COVID Imposed Restrictions | Voice of America - English". www.voanews.com. VOA. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Ariffin, Syed Ahmad Iskandar Syed (2005). Architectural conservation in Islam: case study of the Prophet's Mosque(1st ed.). Skudai, Johor Darul Ta'zim, Malaysia: Penerbit Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. ISBN 9835203733. Retrieved 30 October2016.

- ^ Holloway, Beetle. "Senegal's Grand Magal of Touba: A Pilgrimage of Celebration". Culture Trip. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ uberVU – social comments (5 February 2010). "Friday: 46 Iraqis, 1 Syrian Killed; 169 Iraqis Wounded - Antiwar.com". Original.antiwar.com. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ Aljazeera. "alJazeera Magazine – 41 Martyrs as More than Million People Mark 'Arbaeen' in Holy Karbala". Aljazeera.com. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Powerful Explosions Kill More Than 40 Shi'ite Pilgrims in Karbala". Voanews.com. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 30 June2010.

- ^ Hanun, Abdelamir (5 February 2010). "Blast in crowd kills 41 Shiite pilgrims in Iraq". News.smh.com.au. Retrieved 30 June2010.

- ^ "Sacred Sites: Mashhad, Iran". sacredsites.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 13 March2006.

- ^ Williams, Margaret, 1947- (2013). Jews in a Graeco-Roman environment. Tübingen, Germany. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-16-151901-7. OCLC 855531272.

- ^ "The Western Wall". mosaic.lk.net. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "The Western Wall: History & Overview". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ See David M. Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson, Pilgrimage and the Jews (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006) for history and data on several pilgrimages to both Ashkenazi and Sephardic holy sites.

- ^ Mansukhani, Gobind Singh (1968). Introduction to Sikhism: 100 Basic Questions and Answers on Sikh Religion and History. India Book House. p. 60.

- ^ Myrvold, Kristina (2012). Sikhs Across Borders: Transnational Practices of European Sikhs. A&C Black. p. 178. ISBN 9781441103581.

- ^ "Sikhism". Archived from the original on 23 November 2001.

- ^ "Special train to connect all five Takhats, first run on February 16". Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "沒固定路線、全憑神轎指引徒步400里...白沙屯媽祖進香有何秘密?他爆出這些「神蹟」超驚奇". The Storm Media (in Chinese). Central News Agency (published 19 April 2018). 21 May 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "~ 大甲媽祖遶境進香歷史沿革、陣頭、典禮、禁忌的介紹~". 淨 空 禪 林 (in Chinese). 21 May 2018.

- ^ Aspandyar Sohrab Gotla (2000). "Guide to Zarthoshtrian historical places in Iran." University of Michigan Press. LCCN 2005388611 pg. 164

- ^ Hartman, Sven S. (1980). Parsism: The Religions of Zoroaster. BRILL. p. 20. ISBN 9004062084.

- ^ a b Shelar, Jyoti (1 December 2017). "Pilgrimage or mela? Parsis split on Udvada festival". The Hindu. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Deshmukh, Indumati (1961). "Address in Marathi." The Awakener 7 (3): 29.

- ^ Nielsen, Inge (2017). "Collective mysteries and Greek pilgrimage: The cases of Eleusis, Thebes and Andania, in: Excavating Pilgrimage".

Further reading[edit source]

- al-Naqar, Umar. 1972. The Pilgrimage Tradition in West Africa. Khartoum: Khartoum University Press. [includes a map 'African Pilgrimage Routes to Mecca, ca. 1300–1900']

- Coleman, Simon and John Elsner (1995), Pilgrimage: Past and Present in the World Religions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Coleman, Simon & John Eade (eds) (2005), Reframing Pilgrimage. Cultures in Motion. London: Routledge.

- Davidson, Linda Kay and David M. Gitlitz (2002), Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Ca.: ABC-CLIO.

- Gitlitz, David M. and Linda Kay Davidson (2006). Pilgrimage and the Jews. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Jackowski, Antoni. 1998. Pielgrzymowanie [Pilgrimage]. Wroclaw: Wydawnictwo Dolnoslaskie.

- Kerschbaum & Gattinger, Via Francigena – DVD – Documentation, of a modern pilgrimage to Rome, ISBN 3-200-00500-9, Verlag EUROVIA, Vienna 2005

- Margry, Peter Jan (ed.) (2008), Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World. New Itineraries into the Sacred. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Okamoto, Ryosuke (2019). Pilgrimages in the Secular Age: From El Camino to Anime. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

- Sumption, Jonathan. 2002. Pilgrimage: An Image of Mediaeval Religion. London: Faber and Faber Ltd.

- Wolfe, Michael (ed.). 1997. One Thousands Roads to Mecca. New York: Grove Press.

- Zarnecki, George (1985), The Monastic World: The Contributions of The Orders. pp. 36–66, in Evans, Joan (ed.). 1985. The Flowering of the Middle Ages. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

- Zwissler, Laurel (2011). "Pagan Pilgrimage: New Religious Movements Research on Sacred Travel within Pagan and New Age Communities". Religion Compass. Wiley. 5 (7): 326–342. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2011.00282.x. ISSN 1749-8171.

External links[edit source]

| Library resources about Pilgrimage |

Media related to Pilgrimage at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pilgrimage at Wikimedia Commons

순례

| 이 문서의 내용은 출처가 분명하지 않습니다. (2010년 10월) |

순례(巡禮, 영어: pilgrimage)는 종교적 의무 또는 신앙 고취의 목적으로 하는 여행을 말한다.

기독교[편집]

기독교에서는 4세기 경 예수 그리스도가 태어나고 활동했던 이스라엘을 순례한 사람의 기록이 있으며, 로마나 초기 교회의 사도들이 활동했던 터키·그리스 등도 기독교 성지 순례의 대상이다. 한국에서는 로마 가톨릭교회에서 순교성지, 최초의 사제인 김대건 신부가 유년시절을 보낸 미리내성지등 천주교와 관련된 지역들을 성지로 본다.

이슬람교[편집]

이슬람교에서는 일생에 한 번 메카에 들르는 것을 하즈라 하여 이슬람의 다섯 기둥 가운데 하나이다.

같이 보기[편집]

외부 링크[편집]

위키미디어 공용에 순례 관련 미디어 분류가 있습니다.

위키미디어 공용에 순례 관련 미디어 분류가 있습니다.

| 이 글은 종교에 관한 토막글입니다. 여러분의 지식으로 알차게 문서를 완성해 갑시다. |

巡礼

巡礼(じゅんれい、英: pilgrimage)とは、 日常的な生活空間を一時的に離れて、宗教の聖地や聖域に参詣し、聖なるものにより接近しようとする宗教的行動のこと[1]。 巡礼は世界の多くの宗教で重要な宗教儀礼と見なされており、特にその宗教の信者が特定の地域や文化圏を超えて広域に分布している宗教においてはとりわけ大切なものと位置付けられている[1]。したがって巡礼は、未開宗教よりも歴史的な宗教や世界宗教において、より一層さかんに行われている[1]。

呼称、表現、基本概念[編集]

ヨーロッパ諸語での呼びかたは、例えばフランス語では「pèlerinage ペルリナージュ」、英語では「pilgrimage ピルグリミッジ」、ドイツ語では「Pilgerfahrt ピルゲルファールト」である[1] が、 これらは基本的にラテン語の「peregrinus ペレグリーヌス」を語源としており、その基本的な意味は「通過者」とか「異邦人」である[1]。このラテン語の基本的な意味でも明らかなように、巡礼の根本的なかたちというのは、遠方の聖地に赴く、というところにある[1]。各信者の居住地にも宗教施設(教会堂、仏閣、神社など)は存在するのだが、それらに赴く行為のことを「巡礼」と呼ぶことは無い[1]。したがって、巡礼というのは、我々の居住地、つまり日常空間あるいは俗空間から離脱して、非日常空間あるいは聖空間に入り、そこで聖なるものに接近・接触し、その後ふたたび もとの日常空間・俗空間に復帰する行為、と言うこともできる[1]。 [注 1]

分類、類型[編集]

世界には様々な巡礼があるが、その特色で様々に分類することも可能である[1]。

まずは集団型と個人型である[1]。あらかじめ集団を組んで巡礼に赴く型と、個々人がおのおのの発意によって個々に巡礼に赴く型があるのである[1]。聖地は多くが辺鄙(へんぴ)な場所にあるので、交通手段が未発達の時代においては個人で行うのは困難であった[1](つまりその時代、ほとんどが集団型であった)。また、巡礼は長日数におよび金銭的な準備も必要なので、(今日でも)世界中で集団型巡礼はきわめて盛んである[1]。(なお、大勢でにぎやかに行く巡礼と 独りで黙々と行く巡礼では、その巡礼体験(体験の質)が大きく異なっている[1]。)

他の分類として、巡礼の目的や巡拝者の資格に関して「限定型」と「開放型」がある[1]。たとえばイスラームのメッカ巡礼は聖典コーランに定められておりイスラム教徒以外の立ち入りは厳しく禁止されており[1]、またたとえば比叡山の回峰行は数十キロメートルの行程に散在する聖所を1日で参拝する荒行であるが、これは天台宗の僧侶の資格がある者にだけ許可されている巡礼である[1]。これに対して、信者であっても観光客であっても受け入れ、特に巡拝者を限定しない巡礼もあり、たとえば四国のお遍路がその一例である[1]。

「キリスト教やイスラム教に見られる一つの聖地を訪れる直線型と、インドや東洋で見られる複数の聖地を巡る回国型に分類されている」とも言われる。

ユダヤ教の巡礼[編集]

ソロモン神殿が存在していた時代(紀元前9世紀ころ~紀元前586年)では、ユダヤ教徒にとってエルサレムのソロモン神殿が最も重要な聖地であり、三大巡礼祭、すなわちペサハ(過越)、シャブオット(七週の祭り)、スコット(仮庵の祭り)の時、成人男性で巡礼可能な人は皆、その地の同神殿を訪れコルバン(供物の一種)をささげることが求められた。

その後、ソロモン神殿は破壊され、それでもその神殿は第二神殿、ヘロデ神殿と再建・拡張されたが、紀元70年に再度ローマ帝国軍やアグリッパ2世の軍によって破壊された後は(再建が熱心なユダヤ教徒の切なる願いではあるが)再建は果たされておらず、わずかに残されたかつてのヘロデ神殿周囲の(西側の)外壁の一部分(「嘆きの壁」と呼ばれるもの)が、現在のユダヤ教徒の最も重要な巡礼の場所となっている。

現在のユダヤ教では、嘆きの壁以外にも多くの巡礼の地はあり、たとえばマクペラの洞穴(アブラハムなどが埋葬されているとされる場所)、またツァッディークたちの墓(ベツレヘム、メロン山、ネティヴォ 等々にあるもの)などが巡礼の地となっている。

キリスト教の巡礼[編集]

キリスト教は、当初から殉教者を出したが、その墓所に詣でて敬意を表する信者がいた。これをmartyrium マルティリウムと言う。そうした場所は礼拝の場である教会堂と並び、教会(=キリスト教コミュニティ)にとって重要な場所となった。

4世紀にキリスト教が公認されると、キリスト教発祥の地であるパレスチナ、ことにイエス・キリストの生地であるベツレヘム、受難の地であるエルサレムの遺構に参拝するために信者が旅をするようになった。また各地の殉教者記念堂も巡礼の対象となった。

キリスト教における巡礼は聖地への礼拝だけでなく、巡礼旅の過程も重要視されている。すなわち聖地への旅の過程において、人々は「神との繋がり」を再認識し信仰を強化するのである。ルイス・ブニュエルの映画『銀河』は(en:The Milky Way (1969 film)/fr:La Voie lactée (film, 1969))、サンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラへの巡礼を、「時間と空間を越える神の存在への問いかけの物語」として描いている。

地中海沿岸からヨーロッパ各地に諸聖人の遺骨(聖遺物または不朽体)または十字架、ノアの箱舟の跡などの遺物を祭ったとされる教会、聖堂などが多数あり、そのような地への巡礼が行われた。巡礼は多くの旅人を集めた(『カンタベリー物語』など)。もっとも有名なものには、エレナが発見したとされる十字架の遺物、アルメニア王アブガルス3世enに贈られ、エデッサ(en:Edessa)からコンスタンティノポリスにもたらされた自印聖像(マンドリオン、手で描かれたのではない聖像)、コンスタンティノポリスの聖母マリアの衣、洗礼者ヨハネの首などがある。これらの宝物は中世後期に失われた。また、巡礼者を惹きつけるために他の教会から聖遺物を盗んできたり、偽造するということもあったとされる。また西方では、中世中期からミラノのキリストの聖骸布、聖杯(聖杯伝説や騎士道物語を生み出す元になった)などの伝承が生まれた。

古代後期から、殉教者の遺骨によって奇跡がおき、参拝した巡礼者の中に病気が治癒したり歩けなかった足が動くようになったなどの事例が報告されるようになった。こうした奇跡が起こったということから巡礼者が集まるようになったというものも多い。たとえばピレネー山中のルルドや、カトリックの三大巡礼地の1つサンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラなどである。麦角病(四肢が壊疽したり、精神錯乱を招く)は「巡礼に赴くことで癒える」とされた[注 2]

こうした巡礼の旅で病に倒れた人、宿を求める人を宿泊させた巡礼教会、その小さなものを「hospice ホスピス」と呼んだが、そこでのもてなしから「hospitality ホスピタリティ(歓待)」の語がうまれ、病人の看護などの仕事をする部門が教会の中に作られるようになって今日の英語でいう「hospital ホスピタル」が派生した。ゆえに「hospital ホスピタル」は、「病院」だけではなく、「老人ホーム」「孤児院」の意味も持つ。またhospiceは、現代では終末期の患者が残りの時を過ごす近代的な「ホスピス」の語源となっている。

- カトリック(西方教会)の三大巡礼地

カトリックの三大巡礼地は、ローマのサンピエトロ大聖堂(=聖ペトロが眠る場所)、サンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラ(=9世紀に羊飼いが聖ヤコブの墓を見つけとされる場所)、そしてエルサレムともされる。

正教会の巡礼地としては、アヤ・ソフィア大聖堂(=かつてのビザンティン帝国の首都コンスタンティノープル、つまり現在のイスタンブールにある大聖堂)、アトス山(=東方正教の一大中心地)、聖カタリナ修道院(=モーセが十戒を授けられたとされるシナイ山にある修道院)、エルサレムなどが挙げられる。またロシア内、ロシア正教会に限ると、至聖三者聖セルギイ大修道院(=ラドネジの聖セルギイの不朽体のある場所)なども挙げられる。

- プロテスタントの巡礼に対する態度

宗教改革後、プロテスタントは、巡礼に対して(も)冷淡な態度をとっている[1]。[注 3]

イスラム教の巡礼[編集]

メッカ(マッカ)にあるカアバ神殿へ歩いて向かうこと。アラビア語で「ハッジ」。イスラム教の五行のひとつ。行程に若干異なる点があるが、巡礼にはイスラム教各宗派の信徒が共に参加する。

ヒジュラ暦で12番目の月を「ハッジの月(巡礼月)」と呼び、この月にメッカのカアバへ巡礼することは、特に奨励されている。これを大巡礼と言う。対して、これ以外の月に巡礼することは小巡礼(ウムラ)と言う。例年、ハッジの月には数百万人の巡礼者がメッカに集まる。

巡礼は、体力的、経済的に可能な者に、一生に一度は行なうよう義務付けられている行為であるが、巡礼を果たしたムスリム(イスラム教徒)は、「ハーッジー」と呼ばれ、特に尊敬される。

現在ハッジの希望者数は受け入れ可能人数を超えており、ハッジに参加するにはメッカを管理するサウジアラビア政府の発給する特別ビザが必要。ビザ発給枠はムスリム人口を考慮し各国に割り当てられる。サウジアラビア政府は巡礼地での礼拝時の宗教的興奮において起こると危惧される政治的混乱を恐れている。

聖者の廟への参詣はズィヤーラ(アラビア語: زيارة)と呼ばれてハッジ(巡礼)とは厳格に区別されるが、ズィヤーラの方がむしろ日本でいう巡礼に近い[2]。ズィヤーラははじめシーア派によって体系化され、歴代のイマーム、とくにカルバラーのフサイン廟への参詣が奨励された(アルバイーンも参照)。後にイスラーム世界全体に広がり、各地の聖廟を巡歴する形式や、集団参詣も行われるようになったが、近代になって急激に衰退した[2]。

バハイ教の巡礼[編集]

バハイ教では本来バグダードのバハー・ウッラーの家とシーラーズのバーブの家が巡礼地とされていたが、現在ではこの巡礼は実行不可能である。現在バハイ教で巡礼といった場合、イスラエルのハイファ、アッコ、バフジーへの九日間の巡礼を指す。

ヒンドゥー教の巡礼[編集]

ヒンドゥー教で聖地をティールタ(तीर्थ tīrtha)と呼び、山や川、高名なリシの住居などが巡礼の対象となる。

ヴァーラーナシーのガートはもっとも有名であり、聖なるガンジス河で沐浴をする。ヴァーラーナシーはヒンドゥー教徒にとってもっとも重要な7つの聖都(サプタプリー)のひとつである。サプタプリーの他の6つはアヨーディヤー、マトゥラー、ハリドワール、カーンチープラム、ウッジャイン、ドワールカーである。

インドの東西南北4端にある巡礼地をチャールダームと呼んで重視する。伝説によると、8世紀のシャンカラがこの4つの巡礼地をまわって寺院を建設したと伝える。チャールダームは北のバドリーナート、南のラーメーシュワラム、東のプリー、西のドワールカーがある。4つの巡礼地は遠く離れているためにすべてを巡礼するのは困難だが、多くのヒンドゥー教徒は一生に一度はこの4か所を巡りたいと望んでいる[3]。より容易な巡礼地としてチョーターチャールダームがあり、ヒマラヤ地方のヤムノートリー(ヤムナー川の水源とされる)、ガンゴートリー(ガンジス川の水源とされる)、ケーダールナート、バドリーナートを巡る[3]。

クンブ・メーラを行うプラヤーグ(イラーハーバード)、ハリドワール、ナーシク、ウッジャインの4か所も重要な巡礼地である[3]。

ジャイナ教の巡礼[編集]

ジャイナ教ではヒンドゥー教のような沐浴を否定した。いっぽうジャイナ教の聖地は山の中にあり、24人のティールタンカラが滞在して重要な事績を残した地と伝えられる[4]。

主要な巡礼地にラージギル(ビハール州)、パーラスナート山脈(ジャールカンド州)のシカルジー、アーブー山(ラージャスターン州)、ギルナール山(グジャラート州)、パーリーターナー(グジャラート州)のシャトルンジャヤ山、シュラバナベラゴラ(カルナータカ州)などがある。

仏教の巡礼[編集]

インド(およびネパール)[編集]

釈迦の生誕の地であるカピラバストゥは釈迦晩年に毘瑠璃王により破壊され廃城となった状態であったが、釈迦の死後数百年後には、仏教の僧によって釈迦生誕の地とされるカピラヴァストゥやルンビニ地域への巡礼が行われるようになっていたことが知られている。有名な僧ではたとえば5世紀に法顕、7世紀に玄奘などもカピラバストゥに巡礼で訪れそれを文書に残した。だが,やがて同地域で仏教にかわってヒンドゥー教やイスラム教が信仰されるようになった結果、仏僧による巡礼も途絶えるようになり、14世紀ころにはカピラヴァストゥの場所が分からなくなってしまい、(UNESCOの調査によると)15世紀ころにはルンビニ地域への巡礼も途絶えてしまったようだ、という。

(1956年にビームラーオ・ラームジー・アンベードカルらが始めた仏教復興運動(新仏教運動)によってインドに数十万人の仏教徒が登場し、その結果 仏教の巡礼が再び行われるようになっていった。)

現在の仏僧や仏教徒の巡礼地として有名なところとしては、ルンビニ(生誕地)、ブッダガヤ(成道、つまり悟りに至った地)、サールナート(説法を開始した地)、クシナガラ(入滅した地)の「仏教四大聖地」がある。熱心な仏教徒が世界各地からやって来る。またそれにさらに4カ所を加えた「仏教八大聖地」へ巡礼する人もいる。

チベット[編集]

チベットでは、聖地とされるカイラス山への巡礼が行われる。 12年に一度、「神々が集う」とされる聖なる年、巡礼年を迎える[5]。カイラス山の周囲の巡礼路を、チベット仏教徒は右回りに巡礼する(右繞[6][7])。ボン教徒は左回りに巡礼する(左繞[8])。近年は歩いて巡礼する人が多いが、熱心な人は五体投地によって進む。1回の五体投地で身長分しか進まないので、一周するのに3万5千回ほど五体投地を行うことになる[5]。

メソアメリカの巡礼[編集]

メソアメリカ文明では、洞窟、山岳、湖、泉、川などが、古代から現代にいたるまで信仰の対象になった。人々は聖地を巡礼して、コパル(香)をたき、七面鳥や酒などの捧げ物をする[9]。

16世紀のスペイン人の記録によれば、ユカタン半島のマヤ人はチチェン・イッツァのようなかつての都市、コスメルのような島を巡礼した。また、ナフ・トゥニッチの洞窟は特に重要であり、カラコル、カラクムル、ドス・ピラスなどの遠くの都市から巡礼が訪れたことが洞窟の壁に記されている[10]。

日本における巡礼[編集]

日本の仏教の巡礼[編集]

日本の仏教における巡礼について説明する。

養老2年(718年)、長谷寺の徳道の病の床での夢に閻魔大王が現れ、「世の苦しむ人々のために三十三箇所の観音霊場を作って巡礼を勧めよ」と言い、起請文と三十三の宝印を授けた。夢から覚めた徳道は宝印に従い三十三箇所の霊場を設けるが、世の信仰を得ることが出来ず発展しなかったため、宝印を摂津中山寺で石棺に収めたと伝えられる。

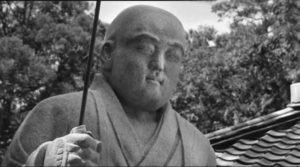

空海(774年-835年)の入定後、修行僧らが空海の足跡を辿って遍歴の旅を始めた。時代が経つにつれ、空海ゆかりの地に加え、修験道の修行地や足摺岬のような補陀洛渡海の出発点となった地などが加わり、四国全体を「修行の場」とみなすような修行を、修行僧や修験者が実行した。こうして密教の修行僧などによって「修行として巡礼」が行われていたわけだが、室町時代にこれが庶民にも広がったと云われている。

寛和2年(986年)、19歳で出家した花山法皇は比叡山で修行の後、三十三箇所観音霊場巡礼を発願し、書写山円教寺の性空と共に中山寺で石棺の宝印を捜し出して永延2年(988年)に紀州熊野から宝印の三十三箇所霊場を巡礼し再興を祈願した。これが現在の西国三十三所の起源といわれている。

源頼朝(1147年 - 1199年)が深い観音信仰を持っていたことから、西国に倣って坂東三十三箇所霊場を発願、実朝の代になって成立したものと考えられている。福島県の八槻都々古別神社観音像の墨書銘に、「僧成弁が三十三箇所巡礼中に八溝山観音堂での三百日参篭中別当の求めによって天福2年(1234年)に観音像を作った」とある。このことからこれ以前に坂東三十三箇所が成立していたとみられる。

平安時代末期には、日本では飢饉が頻繁に起きたり疫病が流行し非常に多くの人々が死に、社会は乱れに乱れ、おまけに日本の仏教も次第に変質し、宗派の僧侶の多くも堕落して戒律を守らなくなってしまったり、人々の心を救うことはなおざりにするようになってしまっていた。まさに仏教で古くから「末法」として予言されていた通りのことが日本で起きてしまっていた。かくして末法思想が人々に支持されるようになった。「末法」になってしまったこの世でどうしたらよいのか? 人々は悩み苦しんだ。末法という悲惨な状況を前にして日本の仏教では、大きく二つの潮流が生じた。

一方の浄土信仰をする人々は、(もうこの世では救われることは絶対に無い、と考えてしまい)遥か西方に「浄土」があると信じ、死後にそこに行けることで救われると信じ、極楽往生を願う巡礼が行われた(後白河法皇(1127年 - 1192年)の熊野詣でなど)。熊野を「極楽浄土の地」としてとらえ、熊野への巡礼がさかんになった。その理由として『日本書紀』の一書に「イザナミノミコトが紀伊国の熊野に葬られた」とされていること、熊野の語源説の一つに「クマ=こもる」で「死者が籠る地」があることで、熊野を「死者の国」とみる考え方がもともとあったため、ともされる。奈良時代より修験道の修行地となっていた熊野三山の本宮を阿弥陀如来の西方極楽浄土、新宮を薬師如来の東方浄瑠璃浄土そして那智大社を「千手観音の南方補陀落浄土」として「現世の浄土の地」と考えることでその信仰が深まったと考えられる。

他方、日蓮(1222年 - 1282年)は「『法華経』二十八品、「妙法蓮華経」こそ釈迦が衆生救済の為に説いた真実の教えであり、この末法の世を正すものである」と説き、この世を諦めてしまって死後の西方浄土を願ったり念仏を唱えたりしてしまうのではなく、法華経を根本にすることで自分の生命のありかたを変えて、この世で実際に幸福を築くべきだと説いた。日蓮は弟子のひとりの(そして役人の仕事をし、仕事上の悩みをかかえた)四条頼基に対して「御みやづかいを法華経とをぼしめせ」つまり「あなたの普段の仕事の場こそが、法華経の行者であるあなたにとっての修行の場だと思いなさい」といった意味の内容を手紙で書いて諭したとされ、日蓮の弟子やその後の信者たちは「普段の仕事の場や普段の生活の場や普段の人間関係の場こそが修行の場である」と考える。そして世界は決して"俗なる場所"と"聖なる場所"に分けられているわけではない、と基本的に考え、巡礼という"聖なる場所"へ行く行為で自分が変われるなどとは期待しておらず、(日蓮の信徒は、本当に大切なのは巡礼ではなくて、普段の自分自身、つまりたとえば普段から自分の根底にある想いをよく選び、普段から全ての人々の幸福を願う想いを持ち、普段から良い言葉を選び周囲の人々に幸福をもたらすような言葉をかけ、普段から 幸福を皆にもたらすような良い行動をすることだ、などと考えているので)、結果として日蓮の信徒はいわゆる「巡礼」に熱中するようなことはあまりない。ただそれでも日蓮宗の多くの宗派では、法華経には「末法の世を救う上行菩薩世が出現する」「末法にこそ本仏が出現する」と予証されていた(予言されていた)と考えはするので、その本仏である日蓮ゆかりの久遠寺、池上本門寺、清澄寺、誕生寺(「日蓮宗四霊場」とも)のほか、鎌倉の地にある日蓮ゆかりの諸寺(安国論寺、長勝寺など)などへ巡礼を行なう人も(若干は)いる。

かくして日本では観音信仰、密教信仰(大師信仰)、浄土信仰、法華経信仰、日蓮への信仰 等々 それぞれの立場で巡礼が行われていたわけであるが、近世に入ると平和な世の中を反映して、庶民が信仰上の巡礼を目的としつつも旅行としても楽しむようになり、巡礼は大衆化した。

富士講の巡礼[編集]

江戸時代にさかんになった富士講では、富士山への巡礼(富士登山)を行い、また富士五湖や白糸の滝などを巡った。富士山までなかなか行くことができない人々は、住まいの近くに富士塚をつくりそこを登った。

お伊勢参り(伊勢講、お蔭参り)[編集]

台湾や韓国での、仏教の日本風巡礼[編集]

寺院に「札所」を定めて行う巡礼は日本固有のもので中国や朝鮮では見られない習慣だが、日本の西国三十三所を写した霊場が20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて韓国や台湾で開創されている。

1984年には日本の楊谷寺の住職により韓国観音霊場が、1997年には同じく日本の永昌寺の住職により台湾三十三観音霊場 が開創されている。更に2008年には韓国の曹渓宗と韓国観光公社が協力して韓の国三十三観音聖地が開創されている。

なお、日本統治時代の朝鮮には寺院統制を目的に主要寺刹として朝鮮三十一本山を指定した他、独立後の韓国の曹渓宗が25教区を定めそれぞれ本寺を置いているが、これらを信仰の対象として巡礼が行われている(いた)かは確認出来ない。

主な霊場や巡礼地[編集]

- ベツレヘム

- エルサレム

- サンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラ

- メッカ(マッカ)…など多数

- セドナ (ネイティブアメリカンのハバスパイ族などの聖地で近年では米国のスピリチュアリストの聖地。)

- 日本

ギャラリー[編集]

脚注[編集]

注

- ^ 明治以降、日本語の「巡禮(巡礼)」も各宗教の聖地を訪ねること全般を指している。そもそも「巡禮」という言葉自体にもともと、「神社や寺院でなければならない」などという意味はまったく込められていない。。 なお日本語では類語に「巡拝(じゅんぱい)」もあるが、「巡礼」は宗教色が強く、「巡拝」はどちらかと言えば観光や娯楽の意味合いが強い[要出典]と言う人もいる。

- ^ 麦角病はライ麦につく麦角菌に起因する病気であるが、巡礼中の断食により、汚染したライ麦を食べなくなったため治ったとも言う。このように「奇跡」とされるものには、科学的に説明がつく例もある。

- ^ プロテスタントの立場としては、そもそも聖書に神ヤハウェやイエスの命令として「(カトリックやオルトドクスの聖地への)巡礼を行え」とは全然書いていないので、聖書に本当に書かれていること(だけ)を重視するプロテスタントの大半の教派としては、巡礼は(/も)人間が勝手に作りだした習慣だと判断され、(カトリックが熱心に巡礼を行っていた歴史を知っているが)それを行ってきたことも間違いなのだ、と判断しているわけである。カトリック教会(や正教会)の幹部の人間の都合で勝手に作りだした諸習慣(悪名高き免罪符や、その他の無数の、教会組織の幹部が(自分に都合よく)勝手に作りだした根拠の無い(奇妙な)習慣)による悪影響を取り除くために命がけで抗議し その間違いを命がけで正した、という起源を持つプロテスタントの立場としては、「巡礼」という習慣(聖書に照らすと、そもそもそれを行なわなければならない根拠が不明で、聖書的には かなり怪しい習慣)に対しても冷淡にならざるを得ないわけである。

出典

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s {スーパーニッポニカ「巡礼」星野英紀 執筆

- ^ a b 大稔哲也「イスラームの巡礼・参詣―エジプトの聖墓参詣を中心に―」『四国遍路と世界の巡礼』法藏館、2007年、169-183頁。ISBN 9784831856814。

- ^ a b c Paul Gwynne (2009). World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction. Blackwell. ISBN 9781405167024

- ^ 渡辺研二『ジャイナ教 非暴力・非所有・非殺生―その教義と実生活』論創社、2005年、293-297頁。ISBN 4846003132。

- ^ a b NHK BS「チベット カイラス巡礼」2015年1月4日放送。

- ^ 精選版 日本国語大辞典『右繞・右遶』 - コトバンク

- ^ 大辞林 第三版『右繞』 - コトバンク

- ^ 日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ)『ボン教』 - コトバンク

- ^ Pilgrimage to Broken Mountain: A Nahua Ritual for Abundant Crops, Aztec Page at Mexicolore

- ^ Witschey, Walter R. T. (2016). “Rites and Rituals”. In Walter R. T. Witschey. Encyclopedia of the Ancient Maya. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 295-296. ISBN 0759122865

参考資料[編集]

- 『坂東札所案内』(清水谷孝尚)

関連書籍[編集]

- 『遍路と巡礼の社会学』(佐藤久光、人文書院、ISBN 4-409-54067-X)

- 『遍路と巡礼の民俗』(佐藤久光、人文書院、ISBN 4-409-54072-6)

Illustration of Shikoku. The bright

Illustration of Shikoku. The bright Larger-than-life statue of Kūkai at

Larger-than-life statue of Kūkai at Pilgrims walk a steep mountian

Pilgrims walk a steep mountian Unpenji gate appearing in the rain. Source: Photo courtesy of the author.

Unpenji gate appearing in the rain. Source: Photo courtesy of the author. Looking down the 1,368 steps on

Looking down the 1,368 steps on Zentsū-ji Temple number seventy-

Zentsū-ji Temple number seventy-