![[지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 이것이 잃어버린 광주소리다 ...명창 박동실을 들어보라](https://image.ajunews.com//content/image/2021/06/23/20210623144535509904_518_323.jpg) [지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 이것이 잃어버린 '광주소리'다 ...명창 박동실을 들어보라박동실(朴東實 1897∽1968) 박동실(朴東實 1897~1968)은 판소리를 통해 항일운동을 한 행동하는 명창이자 이론가였다. 그가 1945년 광복 전후에 창작한 열사가(烈士歌) 중 ‘윤봉길 열사가’의 한 대목을 보자. 윤봉길(尹奉吉) 열사가 1932년 4월 29일 상하이(上海) 홍커우(虹口)공원에서 폭탄을 터트려 시라카와(白川) 대장을 비롯한 일본군 수뇌부를 폭사시킨 그 사건의 그 장면 말이다. “(휘모리) 군중 속에서 어떤 사람이 번개 같이 일어서서 백천 앞으로 우루루루루. 폭탄을 던져 후닥툭탁 와그르르르 불이 번뜻. 백천이 넘어지고 중광이 꺼꾸러지고 야촌이 쓰러지고 시종관이 자빠지다 혼비백산. 오합지졸이 도망하다 넘어지고 뛰어넘다 밟혀죽고…그 때여 윤봉길 씨 두 주먹을 불끈 쥐고…하하 그놈들 잘 죽는다.… 대한독립 만세를 불러노니…” 이 노래를 듣고 조선 사람이라면 누구나 통쾌했을 것이다. 마침 광복이 아닌가.(‘윤봉길 열사가’는 광복 이후 창작됐다는 게 정설이다) 판소리하면 우리는 신재효(申在孝 1812~1884)가 정리한 전승 5가(歌), 곧 수궁가, 심청가, 적벽가, 춘향가, 흥부가를 떠올린다. 박동실은 이 5가를 잘해서 명창이고, 덧붙여 판소리까지 만든 사람이다. 문외한도 술자리에서 한번쯤은 들었을 사철가(사절가)도 그의 작품이다. “이산저산 꽃이 피니 분명코 봄이로다/봄은 찾아왔건마는 세상사 쓸쓸허드라/나도 어제 청춘일러니 오날 백발 한심 허구나/…. “이산 저산 꽃이 피니, 분명코 봄…” 1945년 10월, 광주시 광주극장에선 이 지역 국악인들이 다 모여 해방 기념 공연을 가졌다. 마지막에 출연진 전원이 나와 ‘해방가’를 불렀고, 관객들도 일어나 노래에 맞춰 춤을 추었다. “반가워라 반가워/ 삼천리 강산이 반가워/모두들 나와서 손뼉을 치면서/활기를 내어서 춤을 추어라/이런 경사가 또 있느냐/…/반가워라 반가워라/새로운 아침을 맞이하세/…” 이 해방가도 박동실이 작사 작곡한 것이다(박선홍, 『광주 1백년 2』, 2014년). ‘사철가’와 ‘해방가’는 단가(短歌)여서 완창에 몇 시간씩 걸리는 전승 판소리와는 구별된다. 박동실은 전승 5가에 터를 잡은 양반‧특권층의 판소리를 시대와 함께 하는 판소리, 민족성이 깃든 판소리, 대중성이 살아 있는 판소리로 바꾸었다. 윤봉길 외에도 ’열사가‘의 대상 인물인 이준(李儁 1859~1907), 안중근(安重根 1879~1910), 유관순(柳寬順 1902~1920)의 항일 행적을 비장미 넘치는 판소리에 담음으로써 본격적인 창작 판소리의 시대를 열었다. 그만큼 판소리의 외연을 넓힌 것(정병헌, ‘명창 박동실의 선택과 판소리사적 의의’ 2002년). 물론 ‘열사가’는 광복 전후 문화‧예술계에 불어닥친 항일과 일제 잔재 청산의 분위기 속에서 만들어졌다. 따라서 어디까지가 박동실의 창작물이고, 어디까지가 구전(口傳)인지에 대해선 논란이 있다. 박동실은 1950년 9‧28 서울 수복 후 월북해버려 확인할 수도 없었다. 그럼에도 ‘열사가’는 판소리라는 전통음악의 그릇에 항일이라는 시대정신을 담았다는 것만으로도 민족적, 예술적 의의가 심대하다. 그를 빼고 예향(藝鄕), 광주의 정신을 논할 수 없는 이유다. 박동실은 담양 객사리 241번지에서 태어났지만 제적등본에 따르면 부모는 광주 본촌면 용두리현 북구 용두동 467번지에 살다가 도중에 담양으로 옮겼다고 한다. 1929년 어머니 배금순(裵今巡)이 사망한 곳도 광주 용두리였다고 한다(박선홍, 앞의 책). ‘하얀나비’를 부른 김정호의 외조부 박동실은 대대로 소리하는 집안 출신이다. 9살 때부터 아버지(박장원)에게서 판소리를 배웠는데 아버지와 외할아버지(배희근)도 명창으로 이름을 날렸다. 박동실은 명창 김소희와 같은 집안인 김이채와 결혼해 1남3녀를 뒀다. 이 중 둘째딸(숙자)의 아들, 곧 박동실의 외손자가 ‘이름 모를 소녀’ ‘하얀 나비’ 같은 히트곡을 남긴 송라이터 가수 김정호다. 그는 1985년 34세에 폐렴으로 요절할 때까지도 꽹과리와 북을 손에서 놓지 않았다고 한다. 박동실은 김채만에게 서편제를, 부친에겐 동편제를 배웠다. 제자 한애순(韓愛順1924~2014)은 “선생님은 동편과 서편을 섞어서 소리가 맛있었다.”고 회고했다(배성자, ‘박동실 판소리 연구’, 2008년). 박동실은 스승 김채만(金采萬 1865~1911)의 영향을 주로 받았다. 김채만은 담양의 전설적 명창 이날치(李捺治 1820~1892)를 잇는 서편제의 대가. 그에게서 뻗어나간 소리를 ‘광주소리’라고 하는데, 박동실이 이를 계승 발전시켰다(이경엽, ‘박동실과 담양 판소리의 전통’, 2019). 그의 ‘심청가’가 대표적인 서편제, 박동실제(制) 광주소리다. 서편제는 광주, 나주, 보성, 고창 등 호남의 서남부 평야지역에서 발달한 유파로, 세련된 기교와 섬세한 감성이 부각된다. 동편제는 구례, 남원, 순창, 곡성 등 호남 동부 내륙지방의 유파로 선이 굵고 꿋꿋한 소리제의 특성을 갖는다. 흔히 동편제는 담담하고 채소적(菜蔬的)이며, 천봉월출격(千峯月出格)이고, 서편제는 육미적(肉味的)이며, 만수화란격(萬樹花爛格)이라고들 한다(한국민속예술사전). 박동실은 1930년대 중반, 담양 창평 출신의 후원자 박석기(朴錫驥 1899~1953)를 만나면서부터 후학 양성에 전념하게 된다. 박석기가 담양군 남면 지실마을에 국악초당을 짓고 그를 선생으로 초빙했기 때문이다. 모두 30여명을 가르쳤는데 공부에 게으르면 나이 불문하고 체벌을 가할 만큼 엄격했다고 한다. 김소희, 한애순, 김녹주, 한승호, 박귀희, 장월중선, 김동준, 임춘행, 박후성, 임유앵 등 당대의 명창들이 다 그의 제자다. “어화 세상 벗님네들 이내 한말…” 박동실은 1950년 6‧25전쟁이 나자 월북한다. 친일파의 득세와 소리꾼에 대한 홀대 탓으로 추정된다. 광복 이후 국악계도 일제 청산 문제를 놓고 좌우 갈등을 겪었다. ‘열사가’를 창작한 박동실로서는 친일파가 다시 득세하는 꼴은 견디기 어려웠을 것이다(정병헌, ‘담양소리의 역사적 전개’, 2019년). 박동실의 조카 박종선은 “큰아버지가 북에 간 것은 소리꾼 신분보다 인간적인 대우를 받고 싶었기 때문일 것이다.”고 말했다(김기형, ‘박종선 명인 대담’, 2001년). 박동실은 북에서 인민의 전투적 투쟁심을 고무하는 단가와 장가(長歌) 수십 편을 창작한다. 창극 ‘춘향전’을 현대화하기도 했다. 전통적인 성악 유산을 수집 정리하고 여러 편의 논문도 발표했다. 1957년 9월 김일성이 차려준다는 환갑상과 함께 공훈배우의 칭호를 받았고, 1961년 7월 예술인 최고의 영예인 인민배우가 된다. 그러나 1964년 김일성이 판소리가 양반의 노래이고 듣기 싫은 탁성(濁聲)을 낸다며 불쾌감을 드러낸 이후 판소리는 사라진다. 대신 혁명가극이 등장하고, 박동실은 1968년 12월 4일 71세로 생을 마감한다. 박동실이 월북하면서 그에 관한 모든 게 금기(禁忌)가 됐다. 제자들은 1988년 박동실이 해금(解禁)될 때까지 그에게서 판소리를 배웠다는 사실조차 숨겨야 했다. 판소리의 한 맥(脈)이 끊긴 것이다. 그러나 끊어지면 이어지고, 이어지면 끊어지는 게 세상사. 소리는 梨大 출신 명창에게 이어지고 박동실이 죽기 하루 전날. 남쪽 그의 고향 담양에선 한 여자아이가 태어난다. 그 아이가 명창 권하경(權夏慶‧53). 그는 박동실의 제자 한애순에게 소리를 배워 지금 ‘박동실제 판소리보존회’ 회장을 맡고 있다. 전병헌에 따르면 “한애순은 박동실의 소리를 가장 완벽하게 보유한 명창으로, 그가 광주예술고에서 판소리 선생으로 있을 때 학생이었던 권하경을 만나 박동실제 ‘흥보가’와 ‘심청가’를 그대로 전승했다.”고 한다. 실로 절묘한 인연이다. 환생? 권하경은 ‘흥보가’ 이수자로 국가무형문화재 5호이자, ‘명인’이다. 전남대 예술대 국악과를 거쳐 이화여대 대학원에서 ‘심청가 진계면조에 관한 연구’로 박사학위까지 받았다. 담양창극예술단장, 담양소리전수관장도 맡고 있는 그는 요즘 전주와 서울을 오가며 아이들에게 판소리와 남도민요, 고법(鼓法)과 장구 등을 가르친다. 그에게 판소리의 미래에 대해 물었다. “유네스코(UNESCO)는 2003년 우리 판소리를 무형문화유산으로 지정했지만 박동실 등 주요 명창의 소리는 제대로 계승되지 못했습니다. 죄송함과 책임감을 동시에 느낍니다. 판소리는 한문, 역사. 음악 등 많은 분야를 알아야 할 수 있는 종합예술입니다. 삶의 희로애락을 잘 녹여서 관객에게 전달하려면 끊임없이 공부하고 연습해야 합니다. 흰 종이 위에 한 일(一)자만 그려도 인생이 보이는 판소리를 관객에게 들려주고 싶습니다.” 이경엽 교수는 “박동실제 판소리를 특화한 판소리 감상회를 열어 자연스럽게 관광 상품화해야 한다.”면서 ”음원자료가 특히 중요한데 지금껏 알려진 박동실의 녹음자료는 ‘오케이 레코드’ 12227번에 수록된 ‘흥보가’ 중 ‘흥보치부가’가 유일하다고 지적했다. 정병헌은 “박동실이 월북해 담양소리가 위축됐지만 결과적으로 담양소리는 북한으로 그 영역을 넓힌 셈”이라면서 “남북 사이에 장차 예술교류가 활발해질 때를 대비해 이제라도 담양소리를 복원하고 발전시켜야 한다.”고 했다. ‘사철가’ 끄트머리에서 박동실은 “…국곡투식(國穀偸食-나라의 곡식을 훔쳐 먹음) 허는 놈과 부모불효 허는 놈과 /형제화목 못허는 놈 차례로 잡어다가/저세상 먼저 보내버리고/나머지 벗님네들 서로 모아앉아서/한잔 더먹소 덜먹게 허면서/거드렁거리고 놀아보세”.라고 노래 한다. 남북이 그런 날이 올랑가 모르겠다. 명창 권하경(權夏慶‧53)2021-06-24 21:01:30

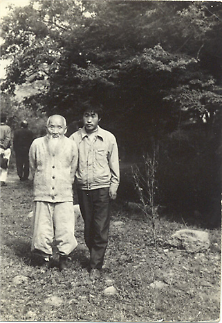

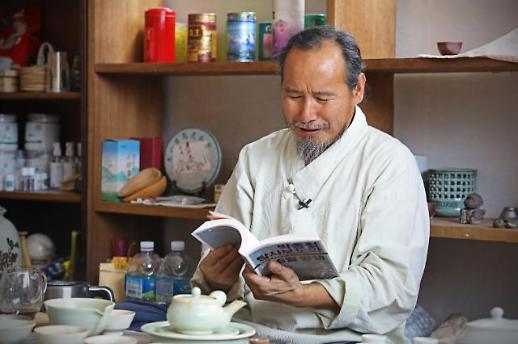

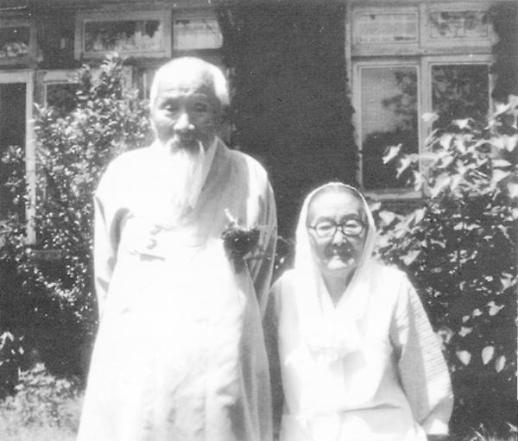

[지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 이것이 잃어버린 '광주소리'다 ...명창 박동실을 들어보라박동실(朴東實 1897∽1968) 박동실(朴東實 1897~1968)은 판소리를 통해 항일운동을 한 행동하는 명창이자 이론가였다. 그가 1945년 광복 전후에 창작한 열사가(烈士歌) 중 ‘윤봉길 열사가’의 한 대목을 보자. 윤봉길(尹奉吉) 열사가 1932년 4월 29일 상하이(上海) 홍커우(虹口)공원에서 폭탄을 터트려 시라카와(白川) 대장을 비롯한 일본군 수뇌부를 폭사시킨 그 사건의 그 장면 말이다. “(휘모리) 군중 속에서 어떤 사람이 번개 같이 일어서서 백천 앞으로 우루루루루. 폭탄을 던져 후닥툭탁 와그르르르 불이 번뜻. 백천이 넘어지고 중광이 꺼꾸러지고 야촌이 쓰러지고 시종관이 자빠지다 혼비백산. 오합지졸이 도망하다 넘어지고 뛰어넘다 밟혀죽고…그 때여 윤봉길 씨 두 주먹을 불끈 쥐고…하하 그놈들 잘 죽는다.… 대한독립 만세를 불러노니…” 이 노래를 듣고 조선 사람이라면 누구나 통쾌했을 것이다. 마침 광복이 아닌가.(‘윤봉길 열사가’는 광복 이후 창작됐다는 게 정설이다) 판소리하면 우리는 신재효(申在孝 1812~1884)가 정리한 전승 5가(歌), 곧 수궁가, 심청가, 적벽가, 춘향가, 흥부가를 떠올린다. 박동실은 이 5가를 잘해서 명창이고, 덧붙여 판소리까지 만든 사람이다. 문외한도 술자리에서 한번쯤은 들었을 사철가(사절가)도 그의 작품이다. “이산저산 꽃이 피니 분명코 봄이로다/봄은 찾아왔건마는 세상사 쓸쓸허드라/나도 어제 청춘일러니 오날 백발 한심 허구나/…. “이산 저산 꽃이 피니, 분명코 봄…” 1945년 10월, 광주시 광주극장에선 이 지역 국악인들이 다 모여 해방 기념 공연을 가졌다. 마지막에 출연진 전원이 나와 ‘해방가’를 불렀고, 관객들도 일어나 노래에 맞춰 춤을 추었다. “반가워라 반가워/ 삼천리 강산이 반가워/모두들 나와서 손뼉을 치면서/활기를 내어서 춤을 추어라/이런 경사가 또 있느냐/…/반가워라 반가워라/새로운 아침을 맞이하세/…” 이 해방가도 박동실이 작사 작곡한 것이다(박선홍, 『광주 1백년 2』, 2014년). ‘사철가’와 ‘해방가’는 단가(短歌)여서 완창에 몇 시간씩 걸리는 전승 판소리와는 구별된다. 박동실은 전승 5가에 터를 잡은 양반‧특권층의 판소리를 시대와 함께 하는 판소리, 민족성이 깃든 판소리, 대중성이 살아 있는 판소리로 바꾸었다. 윤봉길 외에도 ’열사가‘의 대상 인물인 이준(李儁 1859~1907), 안중근(安重根 1879~1910), 유관순(柳寬順 1902~1920)의 항일 행적을 비장미 넘치는 판소리에 담음으로써 본격적인 창작 판소리의 시대를 열었다. 그만큼 판소리의 외연을 넓힌 것(정병헌, ‘명창 박동실의 선택과 판소리사적 의의’ 2002년). 물론 ‘열사가’는 광복 전후 문화‧예술계에 불어닥친 항일과 일제 잔재 청산의 분위기 속에서 만들어졌다. 따라서 어디까지가 박동실의 창작물이고, 어디까지가 구전(口傳)인지에 대해선 논란이 있다. 박동실은 1950년 9‧28 서울 수복 후 월북해버려 확인할 수도 없었다. 그럼에도 ‘열사가’는 판소리라는 전통음악의 그릇에 항일이라는 시대정신을 담았다는 것만으로도 민족적, 예술적 의의가 심대하다. 그를 빼고 예향(藝鄕), 광주의 정신을 논할 수 없는 이유다. 박동실은 담양 객사리 241번지에서 태어났지만 제적등본에 따르면 부모는 광주 본촌면 용두리현 북구 용두동 467번지에 살다가 도중에 담양으로 옮겼다고 한다. 1929년 어머니 배금순(裵今巡)이 사망한 곳도 광주 용두리였다고 한다(박선홍, 앞의 책). ‘하얀나비’를 부른 김정호의 외조부 박동실은 대대로 소리하는 집안 출신이다. 9살 때부터 아버지(박장원)에게서 판소리를 배웠는데 아버지와 외할아버지(배희근)도 명창으로 이름을 날렸다. 박동실은 명창 김소희와 같은 집안인 김이채와 결혼해 1남3녀를 뒀다. 이 중 둘째딸(숙자)의 아들, 곧 박동실의 외손자가 ‘이름 모를 소녀’ ‘하얀 나비’ 같은 히트곡을 남긴 송라이터 가수 김정호다. 그는 1985년 34세에 폐렴으로 요절할 때까지도 꽹과리와 북을 손에서 놓지 않았다고 한다. 박동실은 김채만에게 서편제를, 부친에겐 동편제를 배웠다. 제자 한애순(韓愛順1924~2014)은 “선생님은 동편과 서편을 섞어서 소리가 맛있었다.”고 회고했다(배성자, ‘박동실 판소리 연구’, 2008년). 박동실은 스승 김채만(金采萬 1865~1911)의 영향을 주로 받았다. 김채만은 담양의 전설적 명창 이날치(李捺治 1820~1892)를 잇는 서편제의 대가. 그에게서 뻗어나간 소리를 ‘광주소리’라고 하는데, 박동실이 이를 계승 발전시켰다(이경엽, ‘박동실과 담양 판소리의 전통’, 2019). 그의 ‘심청가’가 대표적인 서편제, 박동실제(制) 광주소리다. 서편제는 광주, 나주, 보성, 고창 등 호남의 서남부 평야지역에서 발달한 유파로, 세련된 기교와 섬세한 감성이 부각된다. 동편제는 구례, 남원, 순창, 곡성 등 호남 동부 내륙지방의 유파로 선이 굵고 꿋꿋한 소리제의 특성을 갖는다. 흔히 동편제는 담담하고 채소적(菜蔬的)이며, 천봉월출격(千峯月出格)이고, 서편제는 육미적(肉味的)이며, 만수화란격(萬樹花爛格)이라고들 한다(한국민속예술사전). 박동실은 1930년대 중반, 담양 창평 출신의 후원자 박석기(朴錫驥 1899~1953)를 만나면서부터 후학 양성에 전념하게 된다. 박석기가 담양군 남면 지실마을에 국악초당을 짓고 그를 선생으로 초빙했기 때문이다. 모두 30여명을 가르쳤는데 공부에 게으르면 나이 불문하고 체벌을 가할 만큼 엄격했다고 한다. 김소희, 한애순, 김녹주, 한승호, 박귀희, 장월중선, 김동준, 임춘행, 박후성, 임유앵 등 당대의 명창들이 다 그의 제자다. “어화 세상 벗님네들 이내 한말…” 박동실은 1950년 6‧25전쟁이 나자 월북한다. 친일파의 득세와 소리꾼에 대한 홀대 탓으로 추정된다. 광복 이후 국악계도 일제 청산 문제를 놓고 좌우 갈등을 겪었다. ‘열사가’를 창작한 박동실로서는 친일파가 다시 득세하는 꼴은 견디기 어려웠을 것이다(정병헌, ‘담양소리의 역사적 전개’, 2019년). 박동실의 조카 박종선은 “큰아버지가 북에 간 것은 소리꾼 신분보다 인간적인 대우를 받고 싶었기 때문일 것이다.”고 말했다(김기형, ‘박종선 명인 대담’, 2001년). 박동실은 북에서 인민의 전투적 투쟁심을 고무하는 단가와 장가(長歌) 수십 편을 창작한다. 창극 ‘춘향전’을 현대화하기도 했다. 전통적인 성악 유산을 수집 정리하고 여러 편의 논문도 발표했다. 1957년 9월 김일성이 차려준다는 환갑상과 함께 공훈배우의 칭호를 받았고, 1961년 7월 예술인 최고의 영예인 인민배우가 된다. 그러나 1964년 김일성이 판소리가 양반의 노래이고 듣기 싫은 탁성(濁聲)을 낸다며 불쾌감을 드러낸 이후 판소리는 사라진다. 대신 혁명가극이 등장하고, 박동실은 1968년 12월 4일 71세로 생을 마감한다. 박동실이 월북하면서 그에 관한 모든 게 금기(禁忌)가 됐다. 제자들은 1988년 박동실이 해금(解禁)될 때까지 그에게서 판소리를 배웠다는 사실조차 숨겨야 했다. 판소리의 한 맥(脈)이 끊긴 것이다. 그러나 끊어지면 이어지고, 이어지면 끊어지는 게 세상사. 소리는 梨大 출신 명창에게 이어지고 박동실이 죽기 하루 전날. 남쪽 그의 고향 담양에선 한 여자아이가 태어난다. 그 아이가 명창 권하경(權夏慶‧53). 그는 박동실의 제자 한애순에게 소리를 배워 지금 ‘박동실제 판소리보존회’ 회장을 맡고 있다. 전병헌에 따르면 “한애순은 박동실의 소리를 가장 완벽하게 보유한 명창으로, 그가 광주예술고에서 판소리 선생으로 있을 때 학생이었던 권하경을 만나 박동실제 ‘흥보가’와 ‘심청가’를 그대로 전승했다.”고 한다. 실로 절묘한 인연이다. 환생? 권하경은 ‘흥보가’ 이수자로 국가무형문화재 5호이자, ‘명인’이다. 전남대 예술대 국악과를 거쳐 이화여대 대학원에서 ‘심청가 진계면조에 관한 연구’로 박사학위까지 받았다. 담양창극예술단장, 담양소리전수관장도 맡고 있는 그는 요즘 전주와 서울을 오가며 아이들에게 판소리와 남도민요, 고법(鼓法)과 장구 등을 가르친다. 그에게 판소리의 미래에 대해 물었다. “유네스코(UNESCO)는 2003년 우리 판소리를 무형문화유산으로 지정했지만 박동실 등 주요 명창의 소리는 제대로 계승되지 못했습니다. 죄송함과 책임감을 동시에 느낍니다. 판소리는 한문, 역사. 음악 등 많은 분야를 알아야 할 수 있는 종합예술입니다. 삶의 희로애락을 잘 녹여서 관객에게 전달하려면 끊임없이 공부하고 연습해야 합니다. 흰 종이 위에 한 일(一)자만 그려도 인생이 보이는 판소리를 관객에게 들려주고 싶습니다.” 이경엽 교수는 “박동실제 판소리를 특화한 판소리 감상회를 열어 자연스럽게 관광 상품화해야 한다.”면서 ”음원자료가 특히 중요한데 지금껏 알려진 박동실의 녹음자료는 ‘오케이 레코드’ 12227번에 수록된 ‘흥보가’ 중 ‘흥보치부가’가 유일하다고 지적했다. 정병헌은 “박동실이 월북해 담양소리가 위축됐지만 결과적으로 담양소리는 북한으로 그 영역을 넓힌 셈”이라면서 “남북 사이에 장차 예술교류가 활발해질 때를 대비해 이제라도 담양소리를 복원하고 발전시켜야 한다.”고 했다. ‘사철가’ 끄트머리에서 박동실은 “…국곡투식(國穀偸食-나라의 곡식을 훔쳐 먹음) 허는 놈과 부모불효 허는 놈과 /형제화목 못허는 놈 차례로 잡어다가/저세상 먼저 보내버리고/나머지 벗님네들 서로 모아앉아서/한잔 더먹소 덜먹게 허면서/거드렁거리고 놀아보세”.라고 노래 한다. 남북이 그런 날이 올랑가 모르겠다. 명창 권하경(權夏慶‧53)2021-06-24 21:01:30 다석 류영모의 생존 직제자 임락경 "그는 3%의 성자"다석이 1981년 91세로 숨을 거둔 지 어언 40년이 넘게 흘러갔다. 다석을 스승으로 모시고 직접 가르침을 받은 제자들은 거의 모두 세상을 떠났다. 다석의 문하에서 배운 제자는 박영호 임락경(1945~ ) 두 사람뿐이다. 임 목사는 열일곱 살에 광주 동광원에 들어가 1년에 두 차례씩 동광원에 와서 강연을 하던 다석을 만났다. 서울 구기동에 살던 다석은 계명산 자락에 있는 벽제 동광원에도 자주 와서 말씀을 전했다. 임 목사는 양주 장흥의 동광원 남자 수도원에 있을 때 계명산을 넘어가 다석의 동광원 강의를 들었다. 임 목사는 다석의 구기동 집에도 박영호 선생과 함께 거의 한 달에 한 번씩 찾아갔다. 순창은 행정구역으로는 전북에 속하지만 지리적으로는 광주에 가깝다. 임 목사가 순창에서 초등학교를 졸업하고 고향을 떠나 찾아간 곳이 동광원이었다. 그는 정확한 연도를 기억하지 못하고 화폐개혁(1962)을 한 해라고 말했다. 임락경 소년은 동광원에서 최흥종 목사(1880~1966)를 만났다. 최 목사는 광주 YMCA 초대 회장을 지냈고 평생을 나환자 돌봄과 빈민구제, 독립운동과 교육에 헌신한 광주의 별이다. 그는 최 목사와 이현필 선생 그리고 다석을 인생의 사표(師表)로 삼았다. 당시 한국은 6·25 전쟁을 겪고 나서 먹을 것이 모자라 대부분 가정에서 1일1식을 했고 좀 여유가 있는 집이라야 1일2식을 하던 때였다. 임 목사는 춘궁기에 2일1식을 한 적도 있었다고 한다. 다석을 알기 전부터 1일1식을 실천한 셈이다. 빈한한 가정에서 태어난 소년으로서 중학교 진학은 꿈도 꿀 수 없었다. 대신 가르침을 얻고자 찾아간 곳이 광주 동광원이다. “남원에 셋이서 공동경영하는 삼일 목공소가 있었습니다. 순창 고향교회의 오북환 장로, 서재선 배영진 집사, 세 분이 목공소를 했습니다. 이현필 선생이 남원을 찾아오면서 크게 감화를 받은 오국환 서지선 집사가 이 선생을 따라가는 바람에 목공소가 해체되다시피 했습니다. 서 집사는 젊은 나이에 돌아가셨습니다. 배영진 집사는 고향교회에서 장로로 있으면서 이현필 류영모 함석헌 선생과 현동완 YMCA 총무님 말씀을 자주 했습니다. 내가 이 이야기를 듣고 ‘조금만 더 크면 이분들을 찾아뵈어야겠다’는 생각을 했습니다. 이른 나이에 동광원에 들어갔는데, 군 생활을 마치고 갔더라면 이현필 최흥종 선생은 못 뵐 뻔했지요. 다석은 해방 이후부터 매년 광주 동광원에 강사로 왔습니다. 강의가 끝나면 선생님과 같은 방에서 잤지요. 새벽 2시에 함께 일어나 같이 요가를 했죠. 가난해서 강사 숙소가 없었던 게 어쩌면 행운이었어요.” 젊은 시절 다석을 댁으로 찾아뵌 임 목사. 다석은 전주 근교에 있던 절 용흥사를 매입해 동광원에 기증했다. 다석이 지은 ‘진달네’라는 시 제목에서 따 진달네 교회라는 이름을 지었다. 다석의 붓글씨를 새겨 현판을 걸었다. 무등산 결핵요양원에서 건강을 회복한 사람들이 전주 진달네 교회로 옮겨와 닭을 기르고 산양 젖을 짜 콜라병에 담아 팔며 자급자족했다. 임 목사도 1969년 군에서 제대한 후 진달네 교회에서 3년 동안 살았다. 다석이 광주 동광원에 강의를 오면 임 목사가 전주로 모시고 가서 진달네 교회에서 하룻밤 묵고 서울로 올라갔다. 다석은 30만원에 절을, 20만원에 인근 산 13 정보를 사서 결핵이 나은 수도자들이 밭을 일구고 살도록 했는데 다석이 세상을 뜬 후 동광원 운영자가 가톨릭 전주교구에 기증했다. 임 목사는 진달네 교회에서 나와 강원용 목사의 크리스챤 아카데미, 가톨릭 농민회 활동을 했다. 그 뒤 화천에서 ‘시골교회’를 개척했다. 군대생활을 할 때 일요일마다 예배 보러 갔던 교회가 있던 마을이었다. 화천과의 인연은 지금까지 55년 넘게 지속되고 있다. 전북 정읍 옥정호반에 있는 근사한 한옥 건물은 화천 시골교회의 부설 요양원 ‘사랑방’이다. 손자의 난치병 치유에 감사한 할머니가 헌금한 돈으로 지었다. 난치병 환자들이 임 목사로부터 민간요법을 배우고 실천하는 곳이다. 임 목사는 낮이면 일하느라 전화를 잘 받지 않았고 저녁에는 묵묵부답. 문자 메시지도 씹었다. 심중식 귀일연구소장과 유희영 군산 YMCA 사무총장의 도움을 받아 인터뷰 날짜를 힘들게 잡았다. 그날 인터뷰어가 서울에서 촬영 기자와 인턴 기자를 태우고 네 시간 운전을 해서 정읍 사랑방에 내려갔다. 그리고 두 시간 인터뷰하고 한 시간 식사하고 다시 다섯 시간 운전을 해서 돌아오는 당일치기 강행군이었다. 임 목사는 밭일을 하던 허름한 옷차림새로 서울서 찾아간 손님을 맞았다. -교회 이름이 하필 시골교회입니까? “내가 최흥종 목사를 알게 되면서 시골교회의 역사가 시작됐습니다. 최 목사는 결핵 환자들과 함께 살았죠. 1980년대 되니까 관절염, 뇌성마비, 전신마비 환자들이 생기더라고요. 그런 사람들이 하나둘 모여서 30명이 됐습니다. 그 당시만 해도 장애인들끼리 사는 건 시설 인가가 나지 않아서 불법이었어요. 교회 차원에서 하면 규제가 덜했죠. 그래서 교회 간판을 걸었습니다. 장로가 교회를 하고 있다간 목사가 바뀌면 끝나니까 ‘내가 목사가 되자’는 생각을 했죠. 늦게 신학을 배워서 목사가 되고 교회 이름을 ‘망할 교회’라고 지으려고 했지요. 수용할 장애인들이 없어져 교회가 망해버려야 좋은 세상이 되거든요. 그런데 신도들이 교회 이름이 마음에 들지 않는다고 화를 냈습니다. 지금 같으면 그냥 밀어붙였을 텐데 그땐 초년 목사라…고향 없는 사람들이 모여서 예배를 보니까 ‘시골 향’ 자를 따서 시골교회라고 했죠. 2010년도까지 30~40년 잘 지냈는데, 지금은 장애인들이 갈 곳이 정말 많아요. 그런데 암환자들이 갈 곳이 없어요. 그래서 이곳 사랑방은 시골교회의 암환자 교육관으로 지은 거예요. 암 환자들 교육을 내가 1년에 30회 이상 나갔습니다. 이 건물에서 암환자들이 모여 숙식까지 할 수 있죠. 여기는 교회라기보다는 사랑방으로 생각하면 좋겠습니다. -광주 YMCA 총무를 지낸 최흥종 목사는 어떤 분이었나요? “다석보다 10년 연상으로 광주 YMCA를 창립하셨죠. 최 목사는 조선이 망해가던 말기에 의병을 살려내기 위해 순검을 했다더군요. 체포된 의병 수십 명을 다음 날 처단해야 하는데 한밤에 최 순검이 ‘너희를 풀어줄 테니 나를 묶어 놓고 도망가라’ 했답니다. 아침에 의병이 다 달아나버린 것이 알려져 난리가 났는데 최 순검은 ‘나 혼자 지키라고 하면 어떡하냐’고 발뺌을 했습니다. 순검을 그만두고 나와서 독립운동을 했는데 3·1운동 때 광주 지역 책임자였어요(최 목사는 서울종로경찰서에서 체포돼 징역 3년을 받았다). 그땐 나병 환자들이 갈 곳이 없었어요. 최흥종 목사가 나병환자들을 위한 시설을 지으라고 선산을 내놓았습니다. 최 목사는 젊은 시절 주먹이 세다고 소문이 나서 나환자들을 지켜주는 데 도움이 됐다고 합니다. 광주에 가면 최 목사가 돌봐준다고 하니 나환자들이 광주로 우르르 몰려왔죠. 도지사한테 나환자를 수용할 집을 지어달라고 여러 차례 건의했는데, 답이 없자 총독부를 찾아가기로 했습니다. 광주에서 걸어서 서울을 향해 출발했습니다. 처음에는 150명이 출발했는데 중간에 숫자가 불어나 500명이 모이더래요. 그것을 ‘구나(救癩)행진’이라고 하는데요. 총독부에선 깜짝 놀랐죠. 그래서 만들어준 곳이 여수 요양원입니다. 여수 요양원 박물관에 가면 최흥종 목사 사진이 걸려 있습니다. 소록도 박물관에도 최 목사 사진이 있죠. 다석 선생이 광주에 올 때면 최흥종 선생과 무척 가깝게 지냈죠.” -다석의 말씀을 직접 들은 사람들이 세상을 뜨고 없어서 보물 같은 존재가 되셨는데요. 다석의 강연은 어땠습니까? “다석 기념 학회나 기념 발표할 때 후진들이 글로만 읽고 발표하니까 다석의 모습을 흉내도 못 내요. 촬영 기자가 왔으니 내가 그 모습을 한번 보여주고 싶습니다. ‘기니디리미비시이지치키티피히’ ‘아야 어여 오요 우유 으이 아오’” 임 목사는 손가락으로 하늘을 가리키며 노래를 하듯 목소리를 높였다. “이건 음성으로 설명하지 않고는 무슨 뜻인지 몰라요. 책에 그저 써놓아도 모르죠. 다석 선생이 하던 모습으로 표현할 수 있는 사람이 없어요. 다석 선생님은 주시경 선생이 큰 실수를 했다고 했죠. 지금의 한글 자모 24자에 옛글자 4자를 그대로 두었더라면 외국어를 표기하는 데도 거리낌이 없었을 것이라는 아쉬움이 있었죠.” 우리가 보통 하는 ‘가나다라마바사…’를 다석은 ‘기니디리’로 대신한 모양이다. 다석은 한글을 사랑했고 한글학자들과 가까워 사전 편찬 비용도 내주었다. 임락경 목사가 개척한 화천 시골교회. 여느 교회와 다르게 한옥으로 지었다. <광명시민신문 제공> -다석에 대해 ‘내가 삶의 큰 빚을 진 스승’이라고 말했던데요. “원래 큰 나무 밑에선 나무가 큰 줄 모르는 거예요. 최초에 최흥종 목사님 영향을 받았고, 이현필, 다석 선생님의 가르침을 받았는데. 세 분 다 나로선 빚쟁이죠.” 이현필의 일생을 알고 나면 보통 사람들이 도저히 따라가기 힘든 성자라는 생각을 하게 된다. 심중식 귀일연구소장 인터뷰 때 가보니 벽제 동광원에 웅장하게 이현필 기념관을 짓고 있었다. 완공 단계에 접어들었다. 이현필 선생은 생전에 그런 기와 집에서 하룻밤도 자보지 못했을 것이다. -심중식 소장이 임락경 목사가 한옥으로 크게 짓자고 해서 그렇게 됐다고 말하더군요. 이곳에 와서 보니 사랑방도 호수가에 한옥으로 멋지게 지었네요. “불교는 어느 나라에 들어가든지 그 나라 건축양식으로 사찰을 짓고 그 나라 옷을 입고 그 나라 악기를 쓰거든요. 기독교는 어느 나라에 가든지 뾰족집 짓고 그 나라 풍속을 안 따라요. 일본에 갔더니 사찰과 신사 건물이 구분 안 될 정도로 비슷해요. 스님들은 일본 정장을 입고 있습니다. 우리나라에서는 한복 잘 입으면 중 옷 같다고 하지요. 다석도 평소에 한복 입고 머리 깎고 다니니 중 같다고 했는데 그게 아니거든요. 건물을 이렇게 지어놓으니 교회가 아니라 절간 같다고 하는데…. 기독교는 여기서 진 거예요. 불교는 건물 하나를 지어놓고 예불도 드리고 교육도 하고 밥도 먹고 잠도 자고 다 하거든요. 그런데 기독교는 이렇게 하려면 건물을 5채 지어야 해요. 예배당 따로, 교육관 따로, 숙소, 식사 따로…. 1채로 해결하는 것이 우리 전통 한옥 방식이죠. 화천의 시골교회도 이렇게 한옥으로 지었어요.” -초등학교만 졸업했다고 하는데요. 책도 10여 권 쓰고 목회자로 활동하시고…. 독학으로 공부를 많이 했다는 인상을 받습니다. “나는 낮에는 한 번도 책을 본 적이 없어요. 지금도 그래요. 밤에 공부했죠. 낮에는 일해야 하죠. 오늘도 여러분들 오기 전까지 부지런히 일했어요. 그리고 아직까지 책 열 권을 안 사봤어요. 아직 삼국지도 안 읽어봤어요. 내 앞에 없으니까. 처음부터 끝까지 읽어본 책이 100권이 안 됩니다. 책 한 권 사고 싶어도 계속 지킨 전통이 깨질까 봐 안 사고 있어요. 대부분 남의 책을 빌려 읽었어요. 공책도 남이 쓰던 것을 썼죠. 밤에 조카나 동생들이 연필로 쓴 헌 공책에 나는 펜으로 덧입혀서 쓰면 되거든요. 학교 안 다니고 공부하는 게 쉬운 게 아니에요. 학교 다닌 사람보다 노력을 배로 해야 해요. 나중에 교수들 하고 회의를 해도 거침없이 말할 수 있어야 하니까.” -김성훈 상지대 총장이 국제환경유기농센터를 설립하면서 임 목사를 교수로 임명했는데 ‘초등학교 졸업자가 대학 교수가 된 것은 처음’이라고 소감을 말했더군요. “김성훈 농림부 장관 때 마침 내가 정농회 회장이었죠. 친하게 지냈어요. 상지대 총장 취임식 날 갔더니 친환경 농업과를 세운다고 하더라고요. 이후에 일부러 찾아갔어요. 친환경 농업과를 설립하는데 친환경 농업이 무언지도 모르는 교수랑 운영하시겠냐고 물었어요. 실제 친환경 농업을 실천한 사람이 교수가 되어야 한다고 했더니, 총장이 학장에게 각 도에 한 명씩 임명하라고 했어요. 강원도의 임락경 등에게 교수 임명장 수여식을 하고 나서 김 총장이 ‘가보로 보관하십시오’라고 해서 화천 집에 임명장을 보관하고 있죠. 미국에서 한 달간 강의 초청이 왔는데 농민과 목사 타이틀로는 비자가 안 나왔어요. 그런데 교수재직 증명서 내니까 금방 나오더라고요. 그래서 미국 가서 한 달간 강의했죠. 서부에서 동부까지 주파했습니다. 가자마자 미주한국일보와 기자 회견했죠. 이현주 목사와 제가 같이 갔어요. 강의는 주로 교민들을 상대로 했죠. 김동성이라는 사람이 중학교 때 나를 따랐는데 미국서 방송을 하고 있었죠. 한인 투표율이 15%였는데, 김동성이 한인 유권자 센터를 만들어서 65%로 끌어올렸어요. 미국 정치인 중에 김동성을 모르는 사람이 없어요. 버락 오바마가 상원의원 때 찾아왔대요. 김동성은 오바마 당선에도 도움을 주고 미국에서 훨훨 날았죠. 김동성을 뉴욕서 만났는데 ‘선생님 내일 방송하셔야 한다’ 하더라고요. 미국에서 방송한다는 것이 신났죠.” -초등학교 학력으로 목사는 어떻게 되셨습니까? “야간 신학대학을 정식으로 다녔습니다. 호헌총회 신학대학입니다. 대한예수교장로회 신학대학이지요.” 대한예수교장로회에도 교단이 많다. 호헌총회는 그중에서도 군소교단이다. 신학대학들은 고졸 학력을 기본으로 요구하지만 농어촌 목회자 특별전형은 학력을 따지지 않는다. 임 목사는 정농회 회장을 했고 상지대 초빙교수를 한 경력으로 특별전형을 통과했다. -기성 대형 교회의 문제점이 무엇이라고 생각하나요? “기독교 방송에서 추석특집이 나가는데, 목사님 교단이 무엇인지 제일 궁금하대요. ‘대한예수팔아 장사회’라고 적어두고 다신 물어보지 말라고 그랬어요. 다른 목사한테 항의가 오면 어떡하냐기에 ‘나한테 바꿔주라’고 했어요. 전화 바꿔주면 ‘당신은 예수 팔아서 장사 안 하냐?’고 물어보려고 했거든요. 상품이 같으면 싸워요. 가게가 나란히 있어도 상품이 다르면 싸우지 않죠. 예수 팔아 장사하는 사람은 나와 싸우겠지만 거룩하게 신앙생활하는 사람들이 나에게 시비를 걸겠느냐 하고 글을 썼더니 다시 한 통화도 안 와요. 그래서 나는 기독교 방송에서 인정해준 대한예수팔아장사회예요. 어디든지 97대 3이라고 하더라고요. 진리를 제대로 하는 것은 3%래요. 제대로 생활하는 사람, 교회, 절이 3%래요. 거기에 다석이 들어간다고 생각합니다. 불교에서 이판사판이 있는데, 이현필 스승님은 ‘이판’이죠. 이판은 청렴결백하게 고기 한 점도 안 먹고 기도만 하는 스님을 말하고, 절 크게 짓고 시주를 좋아하는 걸 사판이라고 하는데요. 나는 이때까지 이판이 훌륭하고 사판은 안 된다고 생각했어요. 불교를 지금까지 유지한 것은 이판이죠, 기독교도 마찬가지죠. 이판 같은 사람이 있으니까 유지됐고, 사판 같은 사람이 욕을 먹었습니다. 그랬더니 <영성가 이야기> 책 쓰기 며칠 전에 훌륭한 사판 스님을 만나서 깜짝 놀랐어요. 이판은 자기 밥벌이도 못 한대요. 포교는 누가 하고 절은 누가 지키냐는 것이죠. 그래서 ‘아 사판 중에서 훌륭한 사람이 있고 이판 중에서도 못된 사람이 있구나’하고 판단했어요. 내가 판단하기엔 사판 중에서도 이판 냄새가 나고 이판 중에서도 사판 냄새가 나야 해요. 이판 쪽으로만 가면 외골수가 되고, 사판 쪽으로만 가면 안 되죠. 둘 다 겸할 수 있는 것이 원칙입니다. 다석은 두 가지를 겸했죠.” 다석 묘소 앞에 선 임락경 목사. -다석은 수행에서 ‘몸성히’를 강조했는데요. 어려서 콜레라로 죽을 고비를 넘긴 뒤론 병을 앓은 적이 없지요. 비결이 궁금합니다. “다석은 체조와 요가를 했는데요. 그 시절에도 인도 요가가 있었다면 굉장히 잘했을 거예요. 다석은 스스로 창안한 요가를 했어요(임 목사는 유튜브 동영상용으로 시범을 보였다). 그 체조를 새벽 2시부터 4시까지 하세요. 두 시간 동안 그 체조만 하는데, 선생님이 허리가 좀 굽으셨거든요. 꼿꼿이 영감님이 왜 그런가 봤더니 앞으로 구부린 체조만 한 거죠. 지금 같으면 뒤로도 펴고 다양한 요가를 했을 텐데…. 그리고 바지 입을 때 손으로 벽 짚지 마라. 목욕탕에서 때 밀어 달라고 하지 마라. 이렇게 생활에서도 요가를 했죠. 내가 한번 선생님께 병원에 간 일이 있냐고 물어봤어요. 그랬더니 2층에서 떨어졌을 때 ‘내가 왜 낮잠을 자지?’ 하고 돌아보니 병원이라고 했어요. 그때 이후론 병원 신세를 진 적이 없었대요. 일제 강점기에 아들 며느리가 모두 홍콩 독감에 걸렸는데 다석은 안 걸렸답니다. 눈병도, 감기도 안 걸렸다고 해요.” -다석의 건강법인 1일1식에 대해서는 어떻게 생각하는지요? “다석 선생님의 1일1식을 따라 해봤어요. 1식도 해보고 2식도 해보고…. 정오가 되기 전에 밥 안 먹기로 결심한 적이 있는데, 아침 4시에 일어나서 타작을 하고, 5시에 밥 먹으러 가면서 산행하는데 배가 고파서 무거운 짐을 들 수가 없더라구요. 밥을 먹으니 둘러멜 수 있었어요. 그래서 일하는 사람이 1일1식은 못 할 일이라고 생각했습니다. 땀 흘리는 일을 안 하는 불한당(不汗黨) 이론에 휘말릴 필요는 없겠다 싶어서 다석 선생께 물어봤어요. 그랬더니 “일하는 사람은 제때 먹어!”라고 했어요. 무릎 꿇고 앉은 모습을 따라 하니까 “그렇게 앉지 마! 일하는 사람은 그러면 안 돼!”라고 했어요. 항상 예외는 있더라고요. 당시에는 다석 선생님을 따라 한다고 1식을 굉장히 오래 했죠. 그런데 일을 못 하겠더라고요. 다석 선생님은 항상 땀 한 번 안 흘리고 사신 것에 미안해해요. 돈을 안 벌어보고 사셨다고 내가 스승을 불한당이라고 하죠. 종로 집에서 태어나 살다가 한 번 이사 가서 십 여 년 살고, 이사 한 번 또 가서 20년 정도 살고, 환갑 지나서 아들이 먹여 살리니까 평생 돈을 안 벌어보셨지요.”<인터뷰어 황호택 논설고문·정리=이주영 인턴기자> <임락경 약력> -1945년생 -1958년 순창 유등국민학교 졸업 -1962년 동광원 입소 -1966~1969 화천에서 육군 복무 -1969~1971 전주 진달네 교회 생활 -1972년 벽제 동광원에서 생활하며 다석을 자주 찾아뵘 -1979년 3월 크리스챤 아카데미 사건으로 구속 수사받음 -2006~2012년 정농회 회장 -2005~2012년 상지대 국제친환경유기농센터 초빙교수 -1980년 화천에 시골교회 세움 -2018년 정읍 옥정호반에 사랑방 개소2021-06-16 17:24:04

다석 류영모의 생존 직제자 임락경 "그는 3%의 성자"다석이 1981년 91세로 숨을 거둔 지 어언 40년이 넘게 흘러갔다. 다석을 스승으로 모시고 직접 가르침을 받은 제자들은 거의 모두 세상을 떠났다. 다석의 문하에서 배운 제자는 박영호 임락경(1945~ ) 두 사람뿐이다. 임 목사는 열일곱 살에 광주 동광원에 들어가 1년에 두 차례씩 동광원에 와서 강연을 하던 다석을 만났다. 서울 구기동에 살던 다석은 계명산 자락에 있는 벽제 동광원에도 자주 와서 말씀을 전했다. 임 목사는 양주 장흥의 동광원 남자 수도원에 있을 때 계명산을 넘어가 다석의 동광원 강의를 들었다. 임 목사는 다석의 구기동 집에도 박영호 선생과 함께 거의 한 달에 한 번씩 찾아갔다. 순창은 행정구역으로는 전북에 속하지만 지리적으로는 광주에 가깝다. 임 목사가 순창에서 초등학교를 졸업하고 고향을 떠나 찾아간 곳이 동광원이었다. 그는 정확한 연도를 기억하지 못하고 화폐개혁(1962)을 한 해라고 말했다. 임락경 소년은 동광원에서 최흥종 목사(1880~1966)를 만났다. 최 목사는 광주 YMCA 초대 회장을 지냈고 평생을 나환자 돌봄과 빈민구제, 독립운동과 교육에 헌신한 광주의 별이다. 그는 최 목사와 이현필 선생 그리고 다석을 인생의 사표(師表)로 삼았다. 당시 한국은 6·25 전쟁을 겪고 나서 먹을 것이 모자라 대부분 가정에서 1일1식을 했고 좀 여유가 있는 집이라야 1일2식을 하던 때였다. 임 목사는 춘궁기에 2일1식을 한 적도 있었다고 한다. 다석을 알기 전부터 1일1식을 실천한 셈이다. 빈한한 가정에서 태어난 소년으로서 중학교 진학은 꿈도 꿀 수 없었다. 대신 가르침을 얻고자 찾아간 곳이 광주 동광원이다. “남원에 셋이서 공동경영하는 삼일 목공소가 있었습니다. 순창 고향교회의 오북환 장로, 서재선 배영진 집사, 세 분이 목공소를 했습니다. 이현필 선생이 남원을 찾아오면서 크게 감화를 받은 오국환 서지선 집사가 이 선생을 따라가는 바람에 목공소가 해체되다시피 했습니다. 서 집사는 젊은 나이에 돌아가셨습니다. 배영진 집사는 고향교회에서 장로로 있으면서 이현필 류영모 함석헌 선생과 현동완 YMCA 총무님 말씀을 자주 했습니다. 내가 이 이야기를 듣고 ‘조금만 더 크면 이분들을 찾아뵈어야겠다’는 생각을 했습니다. 이른 나이에 동광원에 들어갔는데, 군 생활을 마치고 갔더라면 이현필 최흥종 선생은 못 뵐 뻔했지요. 다석은 해방 이후부터 매년 광주 동광원에 강사로 왔습니다. 강의가 끝나면 선생님과 같은 방에서 잤지요. 새벽 2시에 함께 일어나 같이 요가를 했죠. 가난해서 강사 숙소가 없었던 게 어쩌면 행운이었어요.” 젊은 시절 다석을 댁으로 찾아뵌 임 목사. 다석은 전주 근교에 있던 절 용흥사를 매입해 동광원에 기증했다. 다석이 지은 ‘진달네’라는 시 제목에서 따 진달네 교회라는 이름을 지었다. 다석의 붓글씨를 새겨 현판을 걸었다. 무등산 결핵요양원에서 건강을 회복한 사람들이 전주 진달네 교회로 옮겨와 닭을 기르고 산양 젖을 짜 콜라병에 담아 팔며 자급자족했다. 임 목사도 1969년 군에서 제대한 후 진달네 교회에서 3년 동안 살았다. 다석이 광주 동광원에 강의를 오면 임 목사가 전주로 모시고 가서 진달네 교회에서 하룻밤 묵고 서울로 올라갔다. 다석은 30만원에 절을, 20만원에 인근 산 13 정보를 사서 결핵이 나은 수도자들이 밭을 일구고 살도록 했는데 다석이 세상을 뜬 후 동광원 운영자가 가톨릭 전주교구에 기증했다. 임 목사는 진달네 교회에서 나와 강원용 목사의 크리스챤 아카데미, 가톨릭 농민회 활동을 했다. 그 뒤 화천에서 ‘시골교회’를 개척했다. 군대생활을 할 때 일요일마다 예배 보러 갔던 교회가 있던 마을이었다. 화천과의 인연은 지금까지 55년 넘게 지속되고 있다. 전북 정읍 옥정호반에 있는 근사한 한옥 건물은 화천 시골교회의 부설 요양원 ‘사랑방’이다. 손자의 난치병 치유에 감사한 할머니가 헌금한 돈으로 지었다. 난치병 환자들이 임 목사로부터 민간요법을 배우고 실천하는 곳이다. 임 목사는 낮이면 일하느라 전화를 잘 받지 않았고 저녁에는 묵묵부답. 문자 메시지도 씹었다. 심중식 귀일연구소장과 유희영 군산 YMCA 사무총장의 도움을 받아 인터뷰 날짜를 힘들게 잡았다. 그날 인터뷰어가 서울에서 촬영 기자와 인턴 기자를 태우고 네 시간 운전을 해서 정읍 사랑방에 내려갔다. 그리고 두 시간 인터뷰하고 한 시간 식사하고 다시 다섯 시간 운전을 해서 돌아오는 당일치기 강행군이었다. 임 목사는 밭일을 하던 허름한 옷차림새로 서울서 찾아간 손님을 맞았다. -교회 이름이 하필 시골교회입니까? “내가 최흥종 목사를 알게 되면서 시골교회의 역사가 시작됐습니다. 최 목사는 결핵 환자들과 함께 살았죠. 1980년대 되니까 관절염, 뇌성마비, 전신마비 환자들이 생기더라고요. 그런 사람들이 하나둘 모여서 30명이 됐습니다. 그 당시만 해도 장애인들끼리 사는 건 시설 인가가 나지 않아서 불법이었어요. 교회 차원에서 하면 규제가 덜했죠. 그래서 교회 간판을 걸었습니다. 장로가 교회를 하고 있다간 목사가 바뀌면 끝나니까 ‘내가 목사가 되자’는 생각을 했죠. 늦게 신학을 배워서 목사가 되고 교회 이름을 ‘망할 교회’라고 지으려고 했지요. 수용할 장애인들이 없어져 교회가 망해버려야 좋은 세상이 되거든요. 그런데 신도들이 교회 이름이 마음에 들지 않는다고 화를 냈습니다. 지금 같으면 그냥 밀어붙였을 텐데 그땐 초년 목사라…고향 없는 사람들이 모여서 예배를 보니까 ‘시골 향’ 자를 따서 시골교회라고 했죠. 2010년도까지 30~40년 잘 지냈는데, 지금은 장애인들이 갈 곳이 정말 많아요. 그런데 암환자들이 갈 곳이 없어요. 그래서 이곳 사랑방은 시골교회의 암환자 교육관으로 지은 거예요. 암 환자들 교육을 내가 1년에 30회 이상 나갔습니다. 이 건물에서 암환자들이 모여 숙식까지 할 수 있죠. 여기는 교회라기보다는 사랑방으로 생각하면 좋겠습니다. -광주 YMCA 총무를 지낸 최흥종 목사는 어떤 분이었나요? “다석보다 10년 연상으로 광주 YMCA를 창립하셨죠. 최 목사는 조선이 망해가던 말기에 의병을 살려내기 위해 순검을 했다더군요. 체포된 의병 수십 명을 다음 날 처단해야 하는데 한밤에 최 순검이 ‘너희를 풀어줄 테니 나를 묶어 놓고 도망가라’ 했답니다. 아침에 의병이 다 달아나버린 것이 알려져 난리가 났는데 최 순검은 ‘나 혼자 지키라고 하면 어떡하냐’고 발뺌을 했습니다. 순검을 그만두고 나와서 독립운동을 했는데 3·1운동 때 광주 지역 책임자였어요(최 목사는 서울종로경찰서에서 체포돼 징역 3년을 받았다). 그땐 나병 환자들이 갈 곳이 없었어요. 최흥종 목사가 나병환자들을 위한 시설을 지으라고 선산을 내놓았습니다. 최 목사는 젊은 시절 주먹이 세다고 소문이 나서 나환자들을 지켜주는 데 도움이 됐다고 합니다. 광주에 가면 최 목사가 돌봐준다고 하니 나환자들이 광주로 우르르 몰려왔죠. 도지사한테 나환자를 수용할 집을 지어달라고 여러 차례 건의했는데, 답이 없자 총독부를 찾아가기로 했습니다. 광주에서 걸어서 서울을 향해 출발했습니다. 처음에는 150명이 출발했는데 중간에 숫자가 불어나 500명이 모이더래요. 그것을 ‘구나(救癩)행진’이라고 하는데요. 총독부에선 깜짝 놀랐죠. 그래서 만들어준 곳이 여수 요양원입니다. 여수 요양원 박물관에 가면 최흥종 목사 사진이 걸려 있습니다. 소록도 박물관에도 최 목사 사진이 있죠. 다석 선생이 광주에 올 때면 최흥종 선생과 무척 가깝게 지냈죠.” -다석의 말씀을 직접 들은 사람들이 세상을 뜨고 없어서 보물 같은 존재가 되셨는데요. 다석의 강연은 어땠습니까? “다석 기념 학회나 기념 발표할 때 후진들이 글로만 읽고 발표하니까 다석의 모습을 흉내도 못 내요. 촬영 기자가 왔으니 내가 그 모습을 한번 보여주고 싶습니다. ‘기니디리미비시이지치키티피히’ ‘아야 어여 오요 우유 으이 아오’” 임 목사는 손가락으로 하늘을 가리키며 노래를 하듯 목소리를 높였다. “이건 음성으로 설명하지 않고는 무슨 뜻인지 몰라요. 책에 그저 써놓아도 모르죠. 다석 선생이 하던 모습으로 표현할 수 있는 사람이 없어요. 다석 선생님은 주시경 선생이 큰 실수를 했다고 했죠. 지금의 한글 자모 24자에 옛글자 4자를 그대로 두었더라면 외국어를 표기하는 데도 거리낌이 없었을 것이라는 아쉬움이 있었죠.” 우리가 보통 하는 ‘가나다라마바사…’를 다석은 ‘기니디리’로 대신한 모양이다. 다석은 한글을 사랑했고 한글학자들과 가까워 사전 편찬 비용도 내주었다. 임락경 목사가 개척한 화천 시골교회. 여느 교회와 다르게 한옥으로 지었다. <광명시민신문 제공> -다석에 대해 ‘내가 삶의 큰 빚을 진 스승’이라고 말했던데요. “원래 큰 나무 밑에선 나무가 큰 줄 모르는 거예요. 최초에 최흥종 목사님 영향을 받았고, 이현필, 다석 선생님의 가르침을 받았는데. 세 분 다 나로선 빚쟁이죠.” 이현필의 일생을 알고 나면 보통 사람들이 도저히 따라가기 힘든 성자라는 생각을 하게 된다. 심중식 귀일연구소장 인터뷰 때 가보니 벽제 동광원에 웅장하게 이현필 기념관을 짓고 있었다. 완공 단계에 접어들었다. 이현필 선생은 생전에 그런 기와 집에서 하룻밤도 자보지 못했을 것이다. -심중식 소장이 임락경 목사가 한옥으로 크게 짓자고 해서 그렇게 됐다고 말하더군요. 이곳에 와서 보니 사랑방도 호수가에 한옥으로 멋지게 지었네요. “불교는 어느 나라에 들어가든지 그 나라 건축양식으로 사찰을 짓고 그 나라 옷을 입고 그 나라 악기를 쓰거든요. 기독교는 어느 나라에 가든지 뾰족집 짓고 그 나라 풍속을 안 따라요. 일본에 갔더니 사찰과 신사 건물이 구분 안 될 정도로 비슷해요. 스님들은 일본 정장을 입고 있습니다. 우리나라에서는 한복 잘 입으면 중 옷 같다고 하지요. 다석도 평소에 한복 입고 머리 깎고 다니니 중 같다고 했는데 그게 아니거든요. 건물을 이렇게 지어놓으니 교회가 아니라 절간 같다고 하는데…. 기독교는 여기서 진 거예요. 불교는 건물 하나를 지어놓고 예불도 드리고 교육도 하고 밥도 먹고 잠도 자고 다 하거든요. 그런데 기독교는 이렇게 하려면 건물을 5채 지어야 해요. 예배당 따로, 교육관 따로, 숙소, 식사 따로…. 1채로 해결하는 것이 우리 전통 한옥 방식이죠. 화천의 시골교회도 이렇게 한옥으로 지었어요.” -초등학교만 졸업했다고 하는데요. 책도 10여 권 쓰고 목회자로 활동하시고…. 독학으로 공부를 많이 했다는 인상을 받습니다. “나는 낮에는 한 번도 책을 본 적이 없어요. 지금도 그래요. 밤에 공부했죠. 낮에는 일해야 하죠. 오늘도 여러분들 오기 전까지 부지런히 일했어요. 그리고 아직까지 책 열 권을 안 사봤어요. 아직 삼국지도 안 읽어봤어요. 내 앞에 없으니까. 처음부터 끝까지 읽어본 책이 100권이 안 됩니다. 책 한 권 사고 싶어도 계속 지킨 전통이 깨질까 봐 안 사고 있어요. 대부분 남의 책을 빌려 읽었어요. 공책도 남이 쓰던 것을 썼죠. 밤에 조카나 동생들이 연필로 쓴 헌 공책에 나는 펜으로 덧입혀서 쓰면 되거든요. 학교 안 다니고 공부하는 게 쉬운 게 아니에요. 학교 다닌 사람보다 노력을 배로 해야 해요. 나중에 교수들 하고 회의를 해도 거침없이 말할 수 있어야 하니까.” -김성훈 상지대 총장이 국제환경유기농센터를 설립하면서 임 목사를 교수로 임명했는데 ‘초등학교 졸업자가 대학 교수가 된 것은 처음’이라고 소감을 말했더군요. “김성훈 농림부 장관 때 마침 내가 정농회 회장이었죠. 친하게 지냈어요. 상지대 총장 취임식 날 갔더니 친환경 농업과를 세운다고 하더라고요. 이후에 일부러 찾아갔어요. 친환경 농업과를 설립하는데 친환경 농업이 무언지도 모르는 교수랑 운영하시겠냐고 물었어요. 실제 친환경 농업을 실천한 사람이 교수가 되어야 한다고 했더니, 총장이 학장에게 각 도에 한 명씩 임명하라고 했어요. 강원도의 임락경 등에게 교수 임명장 수여식을 하고 나서 김 총장이 ‘가보로 보관하십시오’라고 해서 화천 집에 임명장을 보관하고 있죠. 미국에서 한 달간 강의 초청이 왔는데 농민과 목사 타이틀로는 비자가 안 나왔어요. 그런데 교수재직 증명서 내니까 금방 나오더라고요. 그래서 미국 가서 한 달간 강의했죠. 서부에서 동부까지 주파했습니다. 가자마자 미주한국일보와 기자 회견했죠. 이현주 목사와 제가 같이 갔어요. 강의는 주로 교민들을 상대로 했죠. 김동성이라는 사람이 중학교 때 나를 따랐는데 미국서 방송을 하고 있었죠. 한인 투표율이 15%였는데, 김동성이 한인 유권자 센터를 만들어서 65%로 끌어올렸어요. 미국 정치인 중에 김동성을 모르는 사람이 없어요. 버락 오바마가 상원의원 때 찾아왔대요. 김동성은 오바마 당선에도 도움을 주고 미국에서 훨훨 날았죠. 김동성을 뉴욕서 만났는데 ‘선생님 내일 방송하셔야 한다’ 하더라고요. 미국에서 방송한다는 것이 신났죠.” -초등학교 학력으로 목사는 어떻게 되셨습니까? “야간 신학대학을 정식으로 다녔습니다. 호헌총회 신학대학입니다. 대한예수교장로회 신학대학이지요.” 대한예수교장로회에도 교단이 많다. 호헌총회는 그중에서도 군소교단이다. 신학대학들은 고졸 학력을 기본으로 요구하지만 농어촌 목회자 특별전형은 학력을 따지지 않는다. 임 목사는 정농회 회장을 했고 상지대 초빙교수를 한 경력으로 특별전형을 통과했다. -기성 대형 교회의 문제점이 무엇이라고 생각하나요? “기독교 방송에서 추석특집이 나가는데, 목사님 교단이 무엇인지 제일 궁금하대요. ‘대한예수팔아 장사회’라고 적어두고 다신 물어보지 말라고 그랬어요. 다른 목사한테 항의가 오면 어떡하냐기에 ‘나한테 바꿔주라’고 했어요. 전화 바꿔주면 ‘당신은 예수 팔아서 장사 안 하냐?’고 물어보려고 했거든요. 상품이 같으면 싸워요. 가게가 나란히 있어도 상품이 다르면 싸우지 않죠. 예수 팔아 장사하는 사람은 나와 싸우겠지만 거룩하게 신앙생활하는 사람들이 나에게 시비를 걸겠느냐 하고 글을 썼더니 다시 한 통화도 안 와요. 그래서 나는 기독교 방송에서 인정해준 대한예수팔아장사회예요. 어디든지 97대 3이라고 하더라고요. 진리를 제대로 하는 것은 3%래요. 제대로 생활하는 사람, 교회, 절이 3%래요. 거기에 다석이 들어간다고 생각합니다. 불교에서 이판사판이 있는데, 이현필 스승님은 ‘이판’이죠. 이판은 청렴결백하게 고기 한 점도 안 먹고 기도만 하는 스님을 말하고, 절 크게 짓고 시주를 좋아하는 걸 사판이라고 하는데요. 나는 이때까지 이판이 훌륭하고 사판은 안 된다고 생각했어요. 불교를 지금까지 유지한 것은 이판이죠, 기독교도 마찬가지죠. 이판 같은 사람이 있으니까 유지됐고, 사판 같은 사람이 욕을 먹었습니다. 그랬더니 <영성가 이야기> 책 쓰기 며칠 전에 훌륭한 사판 스님을 만나서 깜짝 놀랐어요. 이판은 자기 밥벌이도 못 한대요. 포교는 누가 하고 절은 누가 지키냐는 것이죠. 그래서 ‘아 사판 중에서 훌륭한 사람이 있고 이판 중에서도 못된 사람이 있구나’하고 판단했어요. 내가 판단하기엔 사판 중에서도 이판 냄새가 나고 이판 중에서도 사판 냄새가 나야 해요. 이판 쪽으로만 가면 외골수가 되고, 사판 쪽으로만 가면 안 되죠. 둘 다 겸할 수 있는 것이 원칙입니다. 다석은 두 가지를 겸했죠.” 다석 묘소 앞에 선 임락경 목사. -다석은 수행에서 ‘몸성히’를 강조했는데요. 어려서 콜레라로 죽을 고비를 넘긴 뒤론 병을 앓은 적이 없지요. 비결이 궁금합니다. “다석은 체조와 요가를 했는데요. 그 시절에도 인도 요가가 있었다면 굉장히 잘했을 거예요. 다석은 스스로 창안한 요가를 했어요(임 목사는 유튜브 동영상용으로 시범을 보였다). 그 체조를 새벽 2시부터 4시까지 하세요. 두 시간 동안 그 체조만 하는데, 선생님이 허리가 좀 굽으셨거든요. 꼿꼿이 영감님이 왜 그런가 봤더니 앞으로 구부린 체조만 한 거죠. 지금 같으면 뒤로도 펴고 다양한 요가를 했을 텐데…. 그리고 바지 입을 때 손으로 벽 짚지 마라. 목욕탕에서 때 밀어 달라고 하지 마라. 이렇게 생활에서도 요가를 했죠. 내가 한번 선생님께 병원에 간 일이 있냐고 물어봤어요. 그랬더니 2층에서 떨어졌을 때 ‘내가 왜 낮잠을 자지?’ 하고 돌아보니 병원이라고 했어요. 그때 이후론 병원 신세를 진 적이 없었대요. 일제 강점기에 아들 며느리가 모두 홍콩 독감에 걸렸는데 다석은 안 걸렸답니다. 눈병도, 감기도 안 걸렸다고 해요.” -다석의 건강법인 1일1식에 대해서는 어떻게 생각하는지요? “다석 선생님의 1일1식을 따라 해봤어요. 1식도 해보고 2식도 해보고…. 정오가 되기 전에 밥 안 먹기로 결심한 적이 있는데, 아침 4시에 일어나서 타작을 하고, 5시에 밥 먹으러 가면서 산행하는데 배가 고파서 무거운 짐을 들 수가 없더라구요. 밥을 먹으니 둘러멜 수 있었어요. 그래서 일하는 사람이 1일1식은 못 할 일이라고 생각했습니다. 땀 흘리는 일을 안 하는 불한당(不汗黨) 이론에 휘말릴 필요는 없겠다 싶어서 다석 선생께 물어봤어요. 그랬더니 “일하는 사람은 제때 먹어!”라고 했어요. 무릎 꿇고 앉은 모습을 따라 하니까 “그렇게 앉지 마! 일하는 사람은 그러면 안 돼!”라고 했어요. 항상 예외는 있더라고요. 당시에는 다석 선생님을 따라 한다고 1식을 굉장히 오래 했죠. 그런데 일을 못 하겠더라고요. 다석 선생님은 항상 땀 한 번 안 흘리고 사신 것에 미안해해요. 돈을 안 벌어보고 사셨다고 내가 스승을 불한당이라고 하죠. 종로 집에서 태어나 살다가 한 번 이사 가서 십 여 년 살고, 이사 한 번 또 가서 20년 정도 살고, 환갑 지나서 아들이 먹여 살리니까 평생 돈을 안 벌어보셨지요.”<인터뷰어 황호택 논설고문·정리=이주영 인턴기자> <임락경 약력> -1945년생 -1958년 순창 유등국민학교 졸업 -1962년 동광원 입소 -1966~1969 화천에서 육군 복무 -1969~1971 전주 진달네 교회 생활 -1972년 벽제 동광원에서 생활하며 다석을 자주 찾아뵘 -1979년 3월 크리스챤 아카데미 사건으로 구속 수사받음 -2006~2012년 정농회 회장 -2005~2012년 상지대 국제친환경유기농센터 초빙교수 -1980년 화천에 시골교회 세움 -2018년 정읍 옥정호반에 사랑방 개소2021-06-16 17:24:04![[중국 심장에 우뚝선 한국로펌] ①광장 중국기업 韓 상장 60% 우리 손에](https://image.ajunews.com//content/image/2021/06/15/20210615172118861417_518_323.jpg) [중국 심장에 우뚝선 한국로펌] ①광장 "중국기업 韓 상장 60% 우리 손에"내년은 한·중수교 30주년이다. 중국은 우리나라 최대 교역국이자 전략적 협력 동반자 지위를 굳건히 하고 있다. 많은 우리 기업이 중국에 진출하는 것과 맞물려 국내 대형 법무법인(로펌)들도 2004년부터 현지에 사무실을 열었다. 한·중수교 30주년을 앞두고 국내 로펌 진출 성과와 계획을 현지 변호사에게 직접 들어본다. <편집자 주> 법무법인 광장 중국 북경사무소 한·중 변호사들. 왼쪽부터 시계 방향으로 이해실(중국)·권현희(중국)·강윤아(한국)·장봉학(중국)·최산운(중국) 변호사. 중국 기업을 상대로 한 성과도 늘고 있다. 세계 게임업계 매출 상위 10위권 기업인 릴리스게임즈와 창유, 선전거래소에 상장한 반도체기업 지앙수야커·배터리제조기업 닝더스다이(CATL), 상하이거래소에 상장한 배터리소재기업 화유구에 등이 한국에 법인을 세울 때 법률 자문을 맡았다. 특히 중국 기업의 한국 상장 부문에선 독보적인 성과를 거두고 있다. 10곳 중 6곳이 광장 북경사무소 도움 아래 성공적으로 상장을 마쳤다. 국내 상장 첫 해외기업인 화풍방직을 비롯해 중국식품포장·에스앤씨엔진그룹·글로벌SM테크·차이나하오란·완리인터내셔널·차이나크리스탈신소재 등이 대표적이다. 광장은 이런 성과를 바탕으로 현지 경쟁력을 높여가고 있다. 강 변호사는 "처음 진출했을 땐 우리 기업 자문 비중이 컸지만 지금은 중국 업체 의뢰가 전체의 절반 이상을 차지한다"며 "앞서 도움을 받았던 중국 회사가 다른 현지 기업을 소개하는 사례가 점점 늘고 있다"고 전했다. 해외 로펌 특성상 중국 내부에선 소송이나 대관 업무를 할 수 없다. 광장은 중국 로펌과 협업해 이런 한계를 극복하고 있다. 국제중재 부문도 강화 중이다. 한국과 중국 기업 간 싱가포르국제중재센터 분쟁이나 중국 업체가 우리 기업을 상대로 제기하는 대한상사중재원 분쟁 중재를 대리한다. 한국에서 민·형사소송이 제기되면 서울 본사에 있는 광장 중재팀·송무팀과 협업해 대응하기도 한다. 강 변호사는 "한국과 중국 모두 대륙법이지만 구체적인 내용은 아주 다르다"며 "북경사무소는 중국 경험이 풍부한 한국 변호사와 우리나라 법률 이해가 높은 중국 변호사가 한·중 양국 기업에 최고 수준의 법률서비스를 제공하고 있다"고 말했다. 그러면서 "수요가 있다면 상하이나 선전에도 사무실을 여는 걸 고려하고 있다"고 덧붙였다.2021-06-16 03:00:00

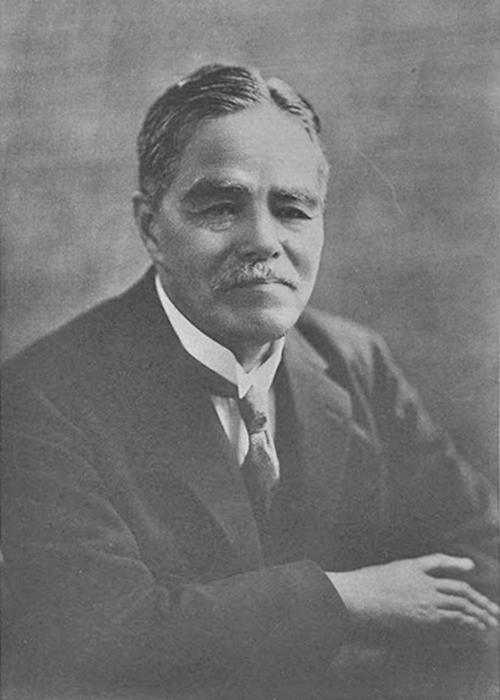

[중국 심장에 우뚝선 한국로펌] ①광장 "중국기업 韓 상장 60% 우리 손에"내년은 한·중수교 30주년이다. 중국은 우리나라 최대 교역국이자 전략적 협력 동반자 지위를 굳건히 하고 있다. 많은 우리 기업이 중국에 진출하는 것과 맞물려 국내 대형 법무법인(로펌)들도 2004년부터 현지에 사무실을 열었다. 한·중수교 30주년을 앞두고 국내 로펌 진출 성과와 계획을 현지 변호사에게 직접 들어본다. <편집자 주> 법무법인 광장 중국 북경사무소 한·중 변호사들. 왼쪽부터 시계 방향으로 이해실(중국)·권현희(중국)·강윤아(한국)·장봉학(중국)·최산운(중국) 변호사. 중국 기업을 상대로 한 성과도 늘고 있다. 세계 게임업계 매출 상위 10위권 기업인 릴리스게임즈와 창유, 선전거래소에 상장한 반도체기업 지앙수야커·배터리제조기업 닝더스다이(CATL), 상하이거래소에 상장한 배터리소재기업 화유구에 등이 한국에 법인을 세울 때 법률 자문을 맡았다. 특히 중국 기업의 한국 상장 부문에선 독보적인 성과를 거두고 있다. 10곳 중 6곳이 광장 북경사무소 도움 아래 성공적으로 상장을 마쳤다. 국내 상장 첫 해외기업인 화풍방직을 비롯해 중국식품포장·에스앤씨엔진그룹·글로벌SM테크·차이나하오란·완리인터내셔널·차이나크리스탈신소재 등이 대표적이다. 광장은 이런 성과를 바탕으로 현지 경쟁력을 높여가고 있다. 강 변호사는 "처음 진출했을 땐 우리 기업 자문 비중이 컸지만 지금은 중국 업체 의뢰가 전체의 절반 이상을 차지한다"며 "앞서 도움을 받았던 중국 회사가 다른 현지 기업을 소개하는 사례가 점점 늘고 있다"고 전했다. 해외 로펌 특성상 중국 내부에선 소송이나 대관 업무를 할 수 없다. 광장은 중국 로펌과 협업해 이런 한계를 극복하고 있다. 국제중재 부문도 강화 중이다. 한국과 중국 기업 간 싱가포르국제중재센터 분쟁이나 중국 업체가 우리 기업을 상대로 제기하는 대한상사중재원 분쟁 중재를 대리한다. 한국에서 민·형사소송이 제기되면 서울 본사에 있는 광장 중재팀·송무팀과 협업해 대응하기도 한다. 강 변호사는 "한국과 중국 모두 대륙법이지만 구체적인 내용은 아주 다르다"며 "북경사무소는 중국 경험이 풍부한 한국 변호사와 우리나라 법률 이해가 높은 중국 변호사가 한·중 양국 기업에 최고 수준의 법률서비스를 제공하고 있다"고 말했다. 그러면서 "수요가 있다면 상하이나 선전에도 사무실을 여는 걸 고려하고 있다"고 덧붙였다.2021-06-16 03:00:00 다석같은 큰 스승 다시보기 어렵습니다정 신부는 <나는 다석을 이렇게 본다> 책 머리에 고은 시인의 <만인보> 중 <유영모>를 옮겨 놓았다. 고은의 시는 다석의 삶을 시적으로 잘 표현했는데 마지막 연이 걸린다. 여기저기 도토리 나무 솎아 베는 나무꾼만 못함이여 무슨 큰 뜻이 있는 듯하나 그저 부질없음이여 -고은의 시가 다석이라는 큰 인물에 대해 불경스러운 표현을 쓴 것 아닌가요? “세계 위인들을 칭송하는 찬탄사도 많고 헐뜯는 말도 많아요. 서울대 법대생 제자가 하루는 다석 선생을 찾아가 물었어요. ‘부처님과 예수님을 비교하면 누가 더 훌륭합니까?’ 다석이 간단하게 대답했습니다. ‘비교 연구해야 하는 일이 참으로 많지만, 비교 연구해서는 안 되는 일도 있는 것이다. 지금 질문이 그러하다.’ 내가 그 책 앞에 고은 시인과 박영호 선생의 시를 함께 실었습니다. 박 선생은 다석을 칭송하는 시를 쓰죠. 그러니 다른 사람들의 눈에 안 들어오는 것이죠. 제자들은 다석이라면 껌뻑 죽습니다. 다석에 대해 조금이라도 비판적인 이야기를 하면 아주 언짢아 해요. 고은 시인은 다석을 주제로 다룬 시에서 무언가 있는 것 같은데 파고 들어가보면 잡히는 것이 없다고 했거든요. 다석을 균형 있게 보라는 소리겠죠. 고은 시인이 근자에 여류 시인 몇 사람에게 고발당했잖아요. 시 한 수 배우러 온 아가씨를 괴롭혔다는 말도 있지요. 나는 개인적으로 사람은 양면성을 지니고 있다고 생각합니다.” -성서신학자로서 다석의 예수 이해가 기독교 전통 안에서 수용 가능할 수 있다고 보는지요? 다석이 기독교 전통 밖으로 나갔다고 보는지요? “수용 가능하지 않습니다. 다석 스스로 정통이 아니라고 말했어요. 일제 강점기 말기에 김교신이 이끈 무교회주의자들이 있습니다. ‘우리는 교회에 모여서 북적거리는 것 싫다’ ‘우리끼리 모여서 목사 없이 설교 없이 성경공부 하겠다’는 무리였죠. 다석은 그 무리에도 끼지 못했어요. 그러니까 15살에 종로5가 연동교회에 다니다가 5년 후 20세에 평안북도 정주 오산학교 선생을 하면서 ‘목사한테 배운 것과 다른 길이 있구나’하고 전통적인 성경 버리고 성경의 진수를 뽑아서 ‘내 맘대로 톨스토이’ 기독교를 새로 세웠거든요, 오산에서 선생으로 있을 적에 동료 선생이 이광수입니다. 그분이 갖고 있던 톨스토이 전집을 빌려서 읽고 정통을 떠나서 이단 기독교인이 된 것이죠. 본인 스스로 ‘이단 기독교인’이라고 그랬습니다. ‘예수에게는 신성과 인성이 있다고 보는 것이 정통 기독교지만, 나는 예수를 무한히 존경해서 나한테는 진짜 스승은 예수 한 분이지만’ 예수님을 일컬어서 대덕사(大德師)라는 칭호를 드린다.’ 덕이 대자로 있는 분이라는 뜻이죠. 부처님이나 공자님에게는 그런 칭호를 안 드렸죠. ‘일생 동안 내가 예수 공부하면서 살지만 그렇다고 해서 예수가 신은 아닌 거다. 예수를 신으로 모시는 것은 과공(過恭)이다’고 보셨어요. 그러니까 전통 기독교를 벗어난 분이죠. ‘그런데 무교회주의자들이 성경을 열심히 공부하는 모임에 가서 내 속 이야기를 하게 되면 충격을 받을 것이다. 사람들이 신앙을 잊어버릴지도 모른다. 그러니까 난 거기에 안 간다’ 하셨죠. 딱 한 번 거기에 가서 설교를 한 적은 있지만 그 얘기까지 하면 너무 기니 생략하지요.” 정양모 교수 정년 퇴임식에서. 왼쪽 끝이 김성수 성공회 대주교, 한 사람 건너 유달영 성천문화재단 이사장, 바로 그 오른쪽이 정 신부. -다석에 대한 김흥호 식 이해와 박영호식 이해 중 어느 것이 다석 본래 사상과 더 가깝다고 평가하는지요? “제가 다석학회를 2005년에 조직하면서 다석의 직제자(直弟子) 두 분을 고문으로 모셨어요. 김흥호 박영호, 이 두 분은 다석이 정통 기독교인이냐, 정통 기독교에서 벗어났느냐를 두고 의견이 갈립니다. 김흥호 목사는 아버지도 목사, 본인도 목사였죠. 그는 이화여대 기독교 학과의 교수였고 교목이었습니다. 그러다 보니 정통 기독교를 옹호할 수밖에 없는 것이죠. 정통 기독교인 가운데서 진짜 기독교인이 우리 선생님 다석이라는 입장일 것이에요. 다석에 대해 비정통이라고 하면 용서 못하죠. 그에 비해 박영호 선생은 무교회주의자, 좋게 얘기하면 다석식 기독교인이죠. 박 선생은 다석이 ‘예수의 신성을 이야기 안했다. 기독교 관점에서 이단자’라고 얘기합니다. 다석 학회 고문으로 두 분을 모시고 있었는데 누구 편을 들어야 할지 10년은 고민했을 것입니다. 다석 강의를 총정리해서 현암사에서 초판을 펴냈습니다. 그리고 두 번째 다석의 저작물은 20년 동안 쓴 다석일지입니다. 절반은 우리말 시조이고, 나머지 절반은 한시입니다. 이분은 우리 말보다 한시가 더 자유로웠던 것 같아요. 한문도 어렵지만 우리말 표현도 옛 말투이고 신조어를 남발했습니다. 세종대왕이 만들어낸 28개의 글자가 부족하다며 더 만들어냈어요. 다석 시조를 읽다가 포기하는 사람도 봤어요. 우리말이지만 불통(不通)이라는 것이죠. 그래서 ‘안 되겠다. 내가 한문에 약하지만 공부해서 밝혀 내야겠다’고 생각했죠. 다석 시조 2500수를 2006년부터 작년까지 십 수년 동안 붙잡고 늘어졌습니다. 다석의 시조 원문, 윤문, 풀이, 이렇게 2500번을 반복해서 원고를 쓰다 보니까 만 페이지가 넘어요. 인쇄해서 800페이지짜리 1,2,3권으로 나옵니다. 그거를 십 수년 동안 매달리고 나서 ‘이게 내 한계다, 내가 아는 것은 이 정도다. 내가 미처 못 본 것은 후학이 알아서 해주길 바란다’고 썼습니다. 그런데 이건 안 팔리는 책이죠. 현암사에 돈을 들고 가서 책을 내달라고 했더니 그 돈으론 어림도 없다고 합니다. ‘몇 천만원 가지곤 안 됩니다. 적자가 너무 커요. 일억 이상 가져오세요’라고 해요. 내가 연금 받아서 겨우 먹고 사는데 그럴 돈이 없잖아요. 그보다 작은 출판사를 찾아갔어요. 길 출판사라고, 거의 알려지지 않은 곳인데 5000만원 줄 테니까 책을 좀 내달라 했더니 기꺼이 내주겠다고 했어요. 그래서 잘 하면, 금년 말에 1,2,3권으로 다석 시조풀이가 나올 것입니다.” 인터뷰어가 “크게 출판기념회도 해야겠어요. 좋은 일이니 사람들에게 알려야죠”라고 했더니 정 신부는 “출판사가 할 일이죠”라고 말했다. 신부도 돈이 들어가는 일에는 기가 죽는 모양이다. -정 신부가 고른 다석의 명언 4가지 중에 “사람을 숭배해서는 안 된다. 그 앞에 절을 할 분은 하나님뿐이다. 종교는 사람 숭배하는 것이 아니다”면서 예수를 하나님과 같은 자리에 올려놓은 것에 대해 비판적으로 얘기했던 데요. 가톨릭이 예수의 어머니인 마리아를 숭배하는 것은 합당하다고 보는지요? “기원후 430년, 제3차 에베소 공의회에서 ‘마리아는 하느님의 어머니’라는 교리를 만든 게 시초입니다. 지중해 사람들, 특히 이탈리아 사람들이 어머니에 대한 공경심이 지극해요. 그것이 예수의 어머니에 대한 공경으로 나타나는 것이 아닐까요. 어머니가 노년기에 접어들게 되면 어머니는 한 집안의 왕초입니다. ‘맘마미아!’ 내 어머니에 대한 존경심이 있죠. 가톨릭과 정교회는 예수님을 공경한다고 하지만 예수님은 두려운 면이 있지만, 성모님은 다 사랑하고 공경하지요. 예수 이외에는 별 볼 일 없다는, 예수 중심의 신심(信心)을 강조하는 교회가 개신교 아닌가요. 그런데 다석은 ‘어머니를 우리가 공경하듯이 성모님을 공경하는 건 당연하다’고 했죠. 다석 말씀에 따르면 한국 아버지는 아들이나 딸이 ‘학교 가는 길에 무언가를 사야 한다’고 말하면 꽥하고 소리를 지르지만, 어머니가 아버지에게 가서 돈을 얻어다 준다는 것이에요. 다석의 경험이에요. 어머니가 간청을 전해준다는 것이죠. 그걸 가톨릭에서는 전구(轉求)라고 합니다. 간청을 아버지 하느님께 전해준다. 우리 일상에서도 아버지를 대하기는 거북하니까 어머니에게 이야기하는 거지요. 그런 인간의 심정이 가톨릭과 정교회의 성모 마리아에도 고스란히 담겨있는 것이며, 비방할 필요가 없다는 것입니다. 다석이 정통 기독교인이라면 이런 말을 죽어도 안 하겠지요. 다석은 자신이 자라난 집안 환경을 생각할 적에 ‘아버지에게 바로 말했다간 혼이 날 수 있으니 어머니에게 말하는 것이 낫더라. 어머니에게 기도하는 것이 나는 이해가 된다’고 한 거죠. 다석이 서양 개신교를 뛰어 넘은 겁니다.” -다석어록 중 ‘사람을 숭배해서는 안 된다’는 말이 다석에게도 그대로 적용되는 가요? “그렇지요. 너무 높이는 것도 안 되죠. 다석 영감도 평생 새벽 3시에 일어나서 세수와 맨손체조 하고 난 뒤 4시부터는 명상에 들어가서 아침 점심 굶고 저녁 드실 때까지 명상을 하셨잖아요. 생각이 딱 떠오르면 시조 한 수를 짓고, 어떤 때에는 생각이 정리 안 되면 날짜만 적었어요. 생각이 용솟음치면 하루에 시조 7수까지 지은 적도 있습니다. 보통은 하루에 시조 1수 또는 한시 1수였죠. 제자들이 말하기를 ‘선생님은 암탉 같아요. 하루에 시를 한 수씩 낳아요’라고 했습니다. 동서고전이나 어떤 사건을 읽고 우리가 무엇을 깨우쳐야 하는지 골똘히 생각해서 탁 트이면 시 한 수가 나오는 것입니다. 참 대단한 어른입니다. 평생 그렇게 사셨거든요. 목사들이 광화문에 모여서 데모하고, 주일마다 목청 돋우어서 설교하고, 굉장히 많은 말을 쏟아 내는데, 언제 명상할 시간이 있겠어요. 다석 닮은 분을 우리 시중에서는 찾아볼 수가 없어요.” -데레사 수녀에게 성녀라는 칭호를 쓰는데. 다석에게도 성자라는 표현을 써도 되지 않을까요? “가톨릭이 공인한 성인은 따로 있죠. 마더 데레사는 공인된 성녀입니다. 한국에서 순교한 1만 천주교 신도들 가운데 로마 교황청에서 103명을 간추려 성인품(聖人品)에 몇 년 전에 올렸어요. 교황청에서 신심이 돈독한 사람이 있다더라 해서 조사를 시작하면 짧게 10년, 길게 몇 십 년, 아주 길게는 몇 백 년 걸립니다. 교황청은 어느 누구가 성인이라고 소문이 나면 진짜 성인인지 조사해서 3단계 칭호를 줍니다. ‘가경자(可敬者)’ ‘복자(福者)’ 그 위에 ‘성인’. 일반 대학에서의 학사, 석사, 박사처럼 나눈 것인데 부질없는 짓이죠. 내면의 됨됨이를 어떻게 조사해서 알겠어요. 이승에서 조사해본들 부질없는 일입니다. 사람의 인품을 등급 매기는 것은 할 짓이 아니라고 생각합니다. 위대한 스승으로 받들면 되지, 큰 칭호를 주려고 애쓸 필요가 없습니다. 다석 같은 분이 5000만 국민 가운데서 다시는 태어나지 않을 것 같아요. 아버지가 가죽을 취급하는 피혁방을 크게 했어요. 아버지는 다석을 위해 적선동에 솜공장을 차려주셨어요. 아버지 3년상을 치르고 나서 가게를 팔아 북한산 밑 구기동 농장으로 이사했습니다. 피혁방과 솜공장을 할 적에 ‘이렇게 수를 부리면 돈이 좀더 벌린다’라는 생각이 있었다고 합니다. 사람이 정직하게 사는 법은 농사밖에 없다고 했죠. 그때만 해도 대학을 나오면 자동적으로 좋은 자리를 차지했어요. 그리고 배운 사람들이 어리숙한 사람들을 등쳐 먹기 일쑤였죠. 그래서 상당히 경제적 여유가 있었음에도 아들 셋 다 고등학교까지 보내고 대학 공부를 안 시켰어요. 그리고 내 아들, 내 제자들은 ‘장가가지 말라’ ‘대학 가지 말라’ ‘오로지 농사를 지어라’하는 세 가지 유언을 남겼죠.” 정양모 신부(오른쪽)을 자택에서 인터뷰하는 황호택 고문. -다석은 종로 상인이던 아버지로부터 많은 재산을 상속받았는데요. 그런데 다석이 자식들에겐 왜 그렇게 했을까요? “부자인 선대에서 물려받은 토지가 상당 부분 있었어요. 소작인들이 찾아와서 생활이 어렵다고 하니 공짜로 땅을 다 넘겨주었어요. 다석은 ‘대학 나오지 말라’ ‘관공서에 취직할 생각하지 말라’ ‘농사지어라’라고 했죠. 그런데 첫째와 셋째는 아버지 말을 안 들었습니다. 첫째는 미국으로, 셋째는 일본으로 이민 갔죠. 90세가 넘을 때까지 거기서 살다가 몇 년 전에 다 죽었습니다. 첫째 셋째 아들은 아버지를 이해하지 못한 거죠. 아버지 장례식에 오지 않았습니다. 그렇지만 한국에서 오는 지인들을 만나면 ‘우리 아버지가 특이한 분인데 어떻게 생각하느냐’ ‘부귀영화를 멀리 했지만 대단히 생각이 고귀한 분’이라는 말을 했답니다. 둘째 아들이 가장 오래 살았습니다. 둘째 아들이 다석학회 연구 활동에 보태 쓰라고 돈을 보낸 적도 있습니다. 미국 아들과 일본 아들도 둘째 아들을 통해 아버지 연구를 위해 쓰라며 돈을 보내주었습니다. 큰돈은 아니지만 가족들의 돈으로 다석학회를 운영한다고 보면 맞습니다. 둘째 아들이 아버지의 뜻을 따라 농사를 짓겠다고 했지만 이미 소작인들에게 땅을 다 나눠주어서 농사 지을 땅이 없는 거예요. 그래서 강원도 화전민 땅에 가서 밭을 일구고 그 옆에 삼형제와 아버지, 어머니가 묻혀있습니다. 부인 목포댁이 다석의 괴팍한 뜻을 다 따랐지만, 두 가지에선 대들었다고 합니다. 아이들이 모두 서울에서 경기고 휘문고 나와서 출중한 데다가 대학 공부시킬 돈이 있는데도, 대학 가면 틀림없이 아랫사람을 짓밟을 가능성이 크다며 안 보냈거든요. 자녀교육을 놓고 목포댁이 다석과 대판 싸웠다고 해요. 다석이 천안 광덕에 있는 땅을 소작인에게 거저 주다시피 했지요. 목포댁은 ‘자식들 농사지으라고 해놓고 땅을 다 남 줘버리면 우리 아들은 어떻게 하느냐’고 불만을 토로한 거죠.” 인터뷰어가 “다석은 세속을 초월한 사람”이라고 거들자 정 신부는 “다석은 출세, 돈벌이, 공명심, 세 가지 욕심을 다 끊은 분”이라고 말했다. -다석과 함석헌 선생의 관계에 대해서도 많은 이야기가 있습니다. 함석헌 선생을 통해 다석을 알게 된 분들이 많지요. 그런가 하면 다석과 함석헌 이 두 분을 모두 따르는 사람도 있고, 그 중 한 분을 더 따르는 사람도 있습니다. 두 분에 대한 평가는 어떤지요? “두 분 다 위대하고. 두 분 다 기이한 면이 있죠. 다석이 오산학교 교장 그만두고 떠날 때 ‘내가 이곳에 온 것은 자네 하나를 만나려는 것인가 봐’라고 할 정도로 제자 함석헌을 애지중지했지요. 함 선생에 대해 우리는 듣기 좋게 ‘실덕(失德)’이라고 말합니다. 성천 유달영 선생한테 자세한 이야기를 들었습니다. 성천도 다석의 제자 중 한 분입니다. 함 선생이 민주화 운동을 하기 전에도 반반한 여자만 보면 가만히 두지 않았다는 겁니다. 다석 일지에 보면 아마 50번 정도 제자를 나무라는 이야기가 나와요. 독한 표현은 안 나와요. 함석헌이라고 이름도 잘 안 나옵니다. ‘함’이라고만 나오죠. 제자 이름을 최대한 노출 안 시키려고 하면서도 새벽 3시에 일어났을 적에 ‘그도 일어났을까’ ‘내가 저를 생각하듯이 저도 나를 생각할까’라고 생각하죠. 제자가 괘씸하지만 잊을 수 없었어요. 함석헌 선생이 등장하는 시조가 50편 이상 나오지 않을까 합니다. 아주 많습니다. 곰곰이 들여다보면 함석헌을 그리워하는 시조라는 것을 알 수 있어요. 그 사정을 잘 아는 성천(유달영)이 ‘함석헌이 자꾸만 여자를 탐하는 것은 병적이다. 정상적인 사람은 그렇지 않다’고 했어요. 정신과 의사에게 보내서 치료를 받게 해야 했는데 우리가 손가락질만 했다'고 후회하는 말을 했습니다. 안타까운 이야기죠. 나처럼 자세히 아는 사람이 많지 않을 것입니다. 나는 다석 일지를 통독했지요. 다석을 존경하는 사람, 제자 함석헌을 존경하는 사람, 둘 다 존경하는 사람이 있을 텐데요. 위대한 민주운동가 함석헌을 공개적으로 나무란 다석이 옳지 않다고 하는 사람도 있고요. 제각각입니다.” 조카뻘 되는 먼 친척이 1980년대 초에 함 선생의 여자관계를 폭로한 책을 안전기획부의 지원을 받아 발간한 적이 있다. 함 선생의 제자인 김용준 전 고려대 교수는 2005년 11월호 <신동아> ‘황호택이 만난 사람’ 인터뷰에서 그 책에 ‘따라다니는 여자는 모두 건드리는 것으로 묘사돼 있다’는 질문을 던지자 “함 선생님을 접해보면 알지, 어떻게 따라다니는 여자를 전부 건드려요”고 반론을 폈다. -함 선생의 여자관계에 대한 팩트는 어느 쪽이 맞는가요. “내가 성천 선생님에게 듣기로는 안기부에서 터뜨린 것이 사실이라고 합니다. 민주화 운동을 포기 안 하면 여성 행각 다 폭로하겠다고 했데요.” 인터뷰어가 “안기부가 협박을 한 거군요”라고 묻자 정 신부는 “네. 없던 사실이 아니라 실제로 여성편력이 화려한 것을 찾아낸 것이죠”라고 답했다. “함 선생에게 ‘민주화운동을 그만두지 않으면 여자관계를 폭로해 만천하의 웃음거리로 만들겠다’고 했답니다. 함 선생은 안기부의 협박을 받고 고민하다가 ‘폭로하라’고 했답니다. 내가 다석의 제자이고 함 선생과도 아주 가까운 성천 선생한테 직접 들었습니다.” 다석 연구와 대중화의 장애물은 그가 쓰는 단어의 난해성(難解性)이다. 훈민정음에도 없는 글자를 새로 만들고 소리글자인 한글을 뜻글자로 활용해 이해하기가 어렵다. -다석 낱말사전은 박영호 선생과 함께 편찬 작업을 하고 있다고 들었습니다. ”아니에요. 박영호 선생한테 완전히 맡겼습니다. 종로2가 YMCA 회관에서 한 강의 1년치를 속기사가 기록했습니다. 아주 악필(惡筆)이에요. 그것을 그냥 읽을 수가 없어서 다석학회에서 고쳐 쓰는데 꼬박 1년이 걸렸어요. 그러고 난 다음에 박영호 선생에게 부탁했습니다. '선생도 연세가 높고, 나도 나이가 지긋하니 우리가 아니면 앞으로 할 사람이 없을 것 같습니다.' 박영호 선생은 다석 낱말사전 하고, 나는 다석 시조 2500수를 맡았지요. 나는 일을 마쳐서 금년 말에 책이 나오기를 기다리고 있죠. 이 책이 나오면 석 박사 공부하는 사람들은 더 편해지겠죠. 이제 한시를 다루는 분이 나와야 하겠습니다. 대만문화대학에서 중국문학박사를 하신 분에게 한시를 맡아달라고 말해보았는데, 중국 사람들이 쓰는 한문과 뜻이 상당히 다르다는 것입니다. 문법도 다르고. 도저히 접근을 못 하겠다고 합니다.” 파티마의 성모 프란체스코 수녀원에서 수녀들과 함께 한 정양모 신부. -서강대 재직시절 예수회와 갈등으로 학교를 떠나셨다면서요? “서강대가 예수회 재단입니다. 예수회수도원 원장, 총장, 이사장, 세 우두머리가 다 예수회원이에요. 서강대학교에서 종교학과를 세우고 난 뒤에 강의계획표를 짜다 보니 박사 학위를 가진 교수가 부족했어요. 예수회원 교수 중 한 명을 제외하고는 박사학위가 없던 사람들입니다. 그래서 나와 서공석 신부, 장익 신부를 불렀어요. 나는 서강대에서 1998년부터 20여년간 근무했어요. 예수회는 그동안 젊은 예수회원들을 외국으로 보내서 박사를 많이 배출했죠. 그러니까 자기네 사람을 쓰고 싶었겠죠. 예수회 재단에서 나와 서공석 신부한테 나가주면 좋겠다고 했죠. 정교수에게 정년을 3년 앞두고 나가 달라는 것은 법적으로 절대 안 될 일이죠. 그쪽에서 나가주기를 간절히 원했지만 내가 법원으로 가져가면 승소하지요. 그러나 천주교 신부가 교수 자리를 두고 법원에서 다툰다는 것이 얼마나 꼴사나운 일이 되겠어요. 정나미가 떨어졌죠. 예수회에서 나를 배척하는 구나 하는 생각이 들었어요. 그래서 법원에 안 가고 사표를 쓰고 나왔어요. 나와서 집에서 1년 정도 쉬고 있는데 성공회대학 이재정 총장이 교파가 다른 데도 나를 교수로 불러줘서 정년퇴직까지 잘 지냈어요. 아마 한국종교 역사상 타교파 대학에 가서 교편을 잡은 사람은 나 혼자일 겁니다. 앞으로도 좀처럼 나오지 않을 거예요.” -이번에 나오는 다석 시조풀이 책에 붙인 다석 연보(年譜)를 만드는데 공을 들였다고 들었습니다. “다석이 잘 안 알려진 분이거든요. 전기로 쓰자면 너무 기니까 연보로 쓴 것이죠. 연보 가운데 가장 감동적인 것은 끝부분 ‘출가(出家)하고 임종’이지요. 그분이 87세가 되었을 적에 출가한 적이 있잖아요. 예수님과 톨스토이 두 분 다 객사(客死)했죠 .” 인터뷰어가 여기서 예수는 객사가 아니라 사형당한 거라고 끼어들자 정 신부는 “집안에서 안 죽으면 객사지요”라고 받았다. “두 분이 모두 객사를 했는데, 어떻게 내가 집에서 편하게 죽을 수가 있는가. 그래서 민증(신분증)을 주머니에 넣고 소나무 숲을 찾아간 거예요. 예수님과 톨스토이의 중생을 생각하며 객사 결심을 한 거라고 생각합니다. 91세로 돌아가셨잖아요. 둘째 아들에게서 딸만 넷이 태어났어요. 다석을 추모하는 모임이 성천문화재단에서 매년 있는데 둘째 아들의 둘째 딸 유희원이 꼭 대표로 참석합니다. 둘째 아들과 며느리가 다석의 임종을 지켜봤어요. 3년 동안 말이 없으셨는데 숨을 몰아쉬다 말고 “아들에게 내 몸을 일으켜 다오”라고 했습니다. 아들이 상반신을 일으켜 주니까 한마디 말도 없이 묵언하던 분이 전력을 다해 ‘아바디’라고 큰 소리를 지르며 돌아가시더라. 하느님에 대한 그리움이 사무쳤다고 해야 할까. 왜 아버지라고 하지 않고 ‘아바디’라고 평안도 말씀을 하셨을까. 김흥호 박영호 선생, 두 분의 풀이가 조금 달라요. 박영호 선생은 ‘아 밝으신 분이여 디디고 서시오’라는 뜻으로 아바디라고 했다는 것입니다. 기록에는 안 남아있어요. 저도 박영호의 뿌리죠. 다석은 ‘내가 죽으면 관을 사지 말아라. 화장터로 가져 가거라”고 했지만 후손들이 유언을 들어주지 않았죠. 화장 대신에 토장을 해서 세 번 옮겼어요. 화장하라는 유언을 안 들어준 게 잘 됐다고 제자들이 말합니다. 선생님 묻혀 있는 곳에 제자들이 참배를 가거든요. 화장해서 뿌렸으면 갈 데가 없었을 거예요. 제자들은 장례식 때 다석의 유언을 지켜야 한다고 했지만 둘째 아들이 안된다고 했습니다. 그렇게 해서 묘소가 남아있게 됐죠. 기일(忌日)에 제자들이 모여 참배할 수 있다는 것만 해도 조그만 뜻이 있겠다 싶어요." 정 신부에게 마지막으로 “다석을 어떤 분이라고 한 문장으로 정리할 수 있느냐”고 묻자 “동방의 큰 스승”이라는 말로 인터뷰를 마무리했다. “이분도 참 외로운 분이었잖아요. 스승이 전혀 없고. 하루 종일 성경 한 구절, 어느 한 단락 물어볼 곳이 없고 참고서가 없으니 혼자 명상을 할 수밖에 없었죠. 항상 명상에 빠져 있던 분이시죠.” 인터뷰를 끝내고 정 신부는 인근의 단골 추어탕 집으로 안내했다. 정 신부는 추어탕 대신에 미꾸라지 튀김을 주문했고 나도 따라갔다. 함께 간 여성 두명(인턴기자와 영상팀 AD)은 처음에는 다른 음식을 찾다가 추어탕으로 돌아왔다. 남의 이야기들 듣는 직업을 가진 사람은 뭐든지 맛있게 잘 먹어야 한다. <인터뷰어=황호택 논설고문·정리 이주영 인턴기자>2021-05-05 16:29:26

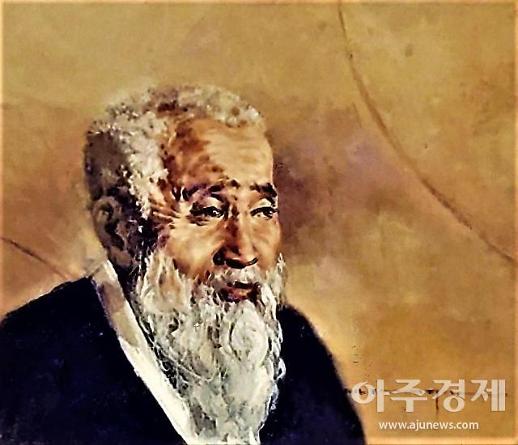

다석같은 큰 스승 다시보기 어렵습니다정 신부는 <나는 다석을 이렇게 본다> 책 머리에 고은 시인의 <만인보> 중 <유영모>를 옮겨 놓았다. 고은의 시는 다석의 삶을 시적으로 잘 표현했는데 마지막 연이 걸린다. 여기저기 도토리 나무 솎아 베는 나무꾼만 못함이여 무슨 큰 뜻이 있는 듯하나 그저 부질없음이여 -고은의 시가 다석이라는 큰 인물에 대해 불경스러운 표현을 쓴 것 아닌가요? “세계 위인들을 칭송하는 찬탄사도 많고 헐뜯는 말도 많아요. 서울대 법대생 제자가 하루는 다석 선생을 찾아가 물었어요. ‘부처님과 예수님을 비교하면 누가 더 훌륭합니까?’ 다석이 간단하게 대답했습니다. ‘비교 연구해야 하는 일이 참으로 많지만, 비교 연구해서는 안 되는 일도 있는 것이다. 지금 질문이 그러하다.’ 내가 그 책 앞에 고은 시인과 박영호 선생의 시를 함께 실었습니다. 박 선생은 다석을 칭송하는 시를 쓰죠. 그러니 다른 사람들의 눈에 안 들어오는 것이죠. 제자들은 다석이라면 껌뻑 죽습니다. 다석에 대해 조금이라도 비판적인 이야기를 하면 아주 언짢아 해요. 고은 시인은 다석을 주제로 다룬 시에서 무언가 있는 것 같은데 파고 들어가보면 잡히는 것이 없다고 했거든요. 다석을 균형 있게 보라는 소리겠죠. 고은 시인이 근자에 여류 시인 몇 사람에게 고발당했잖아요. 시 한 수 배우러 온 아가씨를 괴롭혔다는 말도 있지요. 나는 개인적으로 사람은 양면성을 지니고 있다고 생각합니다.” -성서신학자로서 다석의 예수 이해가 기독교 전통 안에서 수용 가능할 수 있다고 보는지요? 다석이 기독교 전통 밖으로 나갔다고 보는지요? “수용 가능하지 않습니다. 다석 스스로 정통이 아니라고 말했어요. 일제 강점기 말기에 김교신이 이끈 무교회주의자들이 있습니다. ‘우리는 교회에 모여서 북적거리는 것 싫다’ ‘우리끼리 모여서 목사 없이 설교 없이 성경공부 하겠다’는 무리였죠. 다석은 그 무리에도 끼지 못했어요. 그러니까 15살에 종로5가 연동교회에 다니다가 5년 후 20세에 평안북도 정주 오산학교 선생을 하면서 ‘목사한테 배운 것과 다른 길이 있구나’하고 전통적인 성경 버리고 성경의 진수를 뽑아서 ‘내 맘대로 톨스토이’ 기독교를 새로 세웠거든요, 오산에서 선생으로 있을 적에 동료 선생이 이광수입니다. 그분이 갖고 있던 톨스토이 전집을 빌려서 읽고 정통을 떠나서 이단 기독교인이 된 것이죠. 본인 스스로 ‘이단 기독교인’이라고 그랬습니다. ‘예수에게는 신성과 인성이 있다고 보는 것이 정통 기독교지만, 나는 예수를 무한히 존경해서 나한테는 진짜 스승은 예수 한 분이지만’ 예수님을 일컬어서 대덕사(大德師)라는 칭호를 드린다.’ 덕이 대자로 있는 분이라는 뜻이죠. 부처님이나 공자님에게는 그런 칭호를 안 드렸죠. ‘일생 동안 내가 예수 공부하면서 살지만 그렇다고 해서 예수가 신은 아닌 거다. 예수를 신으로 모시는 것은 과공(過恭)이다’고 보셨어요. 그러니까 전통 기독교를 벗어난 분이죠. ‘그런데 무교회주의자들이 성경을 열심히 공부하는 모임에 가서 내 속 이야기를 하게 되면 충격을 받을 것이다. 사람들이 신앙을 잊어버릴지도 모른다. 그러니까 난 거기에 안 간다’ 하셨죠. 딱 한 번 거기에 가서 설교를 한 적은 있지만 그 얘기까지 하면 너무 기니 생략하지요.” 정양모 교수 정년 퇴임식에서. 왼쪽 끝이 김성수 성공회 대주교, 한 사람 건너 유달영 성천문화재단 이사장, 바로 그 오른쪽이 정 신부. -다석에 대한 김흥호 식 이해와 박영호식 이해 중 어느 것이 다석 본래 사상과 더 가깝다고 평가하는지요? “제가 다석학회를 2005년에 조직하면서 다석의 직제자(直弟子) 두 분을 고문으로 모셨어요. 김흥호 박영호, 이 두 분은 다석이 정통 기독교인이냐, 정통 기독교에서 벗어났느냐를 두고 의견이 갈립니다. 김흥호 목사는 아버지도 목사, 본인도 목사였죠. 그는 이화여대 기독교 학과의 교수였고 교목이었습니다. 그러다 보니 정통 기독교를 옹호할 수밖에 없는 것이죠. 정통 기독교인 가운데서 진짜 기독교인이 우리 선생님 다석이라는 입장일 것이에요. 다석에 대해 비정통이라고 하면 용서 못하죠. 그에 비해 박영호 선생은 무교회주의자, 좋게 얘기하면 다석식 기독교인이죠. 박 선생은 다석이 ‘예수의 신성을 이야기 안했다. 기독교 관점에서 이단자’라고 얘기합니다. 다석 학회 고문으로 두 분을 모시고 있었는데 누구 편을 들어야 할지 10년은 고민했을 것입니다. 다석 강의를 총정리해서 현암사에서 초판을 펴냈습니다. 그리고 두 번째 다석의 저작물은 20년 동안 쓴 다석일지입니다. 절반은 우리말 시조이고, 나머지 절반은 한시입니다. 이분은 우리 말보다 한시가 더 자유로웠던 것 같아요. 한문도 어렵지만 우리말 표현도 옛 말투이고 신조어를 남발했습니다. 세종대왕이 만들어낸 28개의 글자가 부족하다며 더 만들어냈어요. 다석 시조를 읽다가 포기하는 사람도 봤어요. 우리말이지만 불통(不通)이라는 것이죠. 그래서 ‘안 되겠다. 내가 한문에 약하지만 공부해서 밝혀 내야겠다’고 생각했죠. 다석 시조 2500수를 2006년부터 작년까지 십 수년 동안 붙잡고 늘어졌습니다. 다석의 시조 원문, 윤문, 풀이, 이렇게 2500번을 반복해서 원고를 쓰다 보니까 만 페이지가 넘어요. 인쇄해서 800페이지짜리 1,2,3권으로 나옵니다. 그거를 십 수년 동안 매달리고 나서 ‘이게 내 한계다, 내가 아는 것은 이 정도다. 내가 미처 못 본 것은 후학이 알아서 해주길 바란다’고 썼습니다. 그런데 이건 안 팔리는 책이죠. 현암사에 돈을 들고 가서 책을 내달라고 했더니 그 돈으론 어림도 없다고 합니다. ‘몇 천만원 가지곤 안 됩니다. 적자가 너무 커요. 일억 이상 가져오세요’라고 해요. 내가 연금 받아서 겨우 먹고 사는데 그럴 돈이 없잖아요. 그보다 작은 출판사를 찾아갔어요. 길 출판사라고, 거의 알려지지 않은 곳인데 5000만원 줄 테니까 책을 좀 내달라 했더니 기꺼이 내주겠다고 했어요. 그래서 잘 하면, 금년 말에 1,2,3권으로 다석 시조풀이가 나올 것입니다.” 인터뷰어가 “크게 출판기념회도 해야겠어요. 좋은 일이니 사람들에게 알려야죠”라고 했더니 정 신부는 “출판사가 할 일이죠”라고 말했다. 신부도 돈이 들어가는 일에는 기가 죽는 모양이다. -정 신부가 고른 다석의 명언 4가지 중에 “사람을 숭배해서는 안 된다. 그 앞에 절을 할 분은 하나님뿐이다. 종교는 사람 숭배하는 것이 아니다”면서 예수를 하나님과 같은 자리에 올려놓은 것에 대해 비판적으로 얘기했던 데요. 가톨릭이 예수의 어머니인 마리아를 숭배하는 것은 합당하다고 보는지요? “기원후 430년, 제3차 에베소 공의회에서 ‘마리아는 하느님의 어머니’라는 교리를 만든 게 시초입니다. 지중해 사람들, 특히 이탈리아 사람들이 어머니에 대한 공경심이 지극해요. 그것이 예수의 어머니에 대한 공경으로 나타나는 것이 아닐까요. 어머니가 노년기에 접어들게 되면 어머니는 한 집안의 왕초입니다. ‘맘마미아!’ 내 어머니에 대한 존경심이 있죠. 가톨릭과 정교회는 예수님을 공경한다고 하지만 예수님은 두려운 면이 있지만, 성모님은 다 사랑하고 공경하지요. 예수 이외에는 별 볼 일 없다는, 예수 중심의 신심(信心)을 강조하는 교회가 개신교 아닌가요. 그런데 다석은 ‘어머니를 우리가 공경하듯이 성모님을 공경하는 건 당연하다’고 했죠. 다석 말씀에 따르면 한국 아버지는 아들이나 딸이 ‘학교 가는 길에 무언가를 사야 한다’고 말하면 꽥하고 소리를 지르지만, 어머니가 아버지에게 가서 돈을 얻어다 준다는 것이에요. 다석의 경험이에요. 어머니가 간청을 전해준다는 것이죠. 그걸 가톨릭에서는 전구(轉求)라고 합니다. 간청을 아버지 하느님께 전해준다. 우리 일상에서도 아버지를 대하기는 거북하니까 어머니에게 이야기하는 거지요. 그런 인간의 심정이 가톨릭과 정교회의 성모 마리아에도 고스란히 담겨있는 것이며, 비방할 필요가 없다는 것입니다. 다석이 정통 기독교인이라면 이런 말을 죽어도 안 하겠지요. 다석은 자신이 자라난 집안 환경을 생각할 적에 ‘아버지에게 바로 말했다간 혼이 날 수 있으니 어머니에게 말하는 것이 낫더라. 어머니에게 기도하는 것이 나는 이해가 된다’고 한 거죠. 다석이 서양 개신교를 뛰어 넘은 겁니다.” -다석어록 중 ‘사람을 숭배해서는 안 된다’는 말이 다석에게도 그대로 적용되는 가요? “그렇지요. 너무 높이는 것도 안 되죠. 다석 영감도 평생 새벽 3시에 일어나서 세수와 맨손체조 하고 난 뒤 4시부터는 명상에 들어가서 아침 점심 굶고 저녁 드실 때까지 명상을 하셨잖아요. 생각이 딱 떠오르면 시조 한 수를 짓고, 어떤 때에는 생각이 정리 안 되면 날짜만 적었어요. 생각이 용솟음치면 하루에 시조 7수까지 지은 적도 있습니다. 보통은 하루에 시조 1수 또는 한시 1수였죠. 제자들이 말하기를 ‘선생님은 암탉 같아요. 하루에 시를 한 수씩 낳아요’라고 했습니다. 동서고전이나 어떤 사건을 읽고 우리가 무엇을 깨우쳐야 하는지 골똘히 생각해서 탁 트이면 시 한 수가 나오는 것입니다. 참 대단한 어른입니다. 평생 그렇게 사셨거든요. 목사들이 광화문에 모여서 데모하고, 주일마다 목청 돋우어서 설교하고, 굉장히 많은 말을 쏟아 내는데, 언제 명상할 시간이 있겠어요. 다석 닮은 분을 우리 시중에서는 찾아볼 수가 없어요.” -데레사 수녀에게 성녀라는 칭호를 쓰는데. 다석에게도 성자라는 표현을 써도 되지 않을까요? “가톨릭이 공인한 성인은 따로 있죠. 마더 데레사는 공인된 성녀입니다. 한국에서 순교한 1만 천주교 신도들 가운데 로마 교황청에서 103명을 간추려 성인품(聖人品)에 몇 년 전에 올렸어요. 교황청에서 신심이 돈독한 사람이 있다더라 해서 조사를 시작하면 짧게 10년, 길게 몇 십 년, 아주 길게는 몇 백 년 걸립니다. 교황청은 어느 누구가 성인이라고 소문이 나면 진짜 성인인지 조사해서 3단계 칭호를 줍니다. ‘가경자(可敬者)’ ‘복자(福者)’ 그 위에 ‘성인’. 일반 대학에서의 학사, 석사, 박사처럼 나눈 것인데 부질없는 짓이죠. 내면의 됨됨이를 어떻게 조사해서 알겠어요. 이승에서 조사해본들 부질없는 일입니다. 사람의 인품을 등급 매기는 것은 할 짓이 아니라고 생각합니다. 위대한 스승으로 받들면 되지, 큰 칭호를 주려고 애쓸 필요가 없습니다. 다석 같은 분이 5000만 국민 가운데서 다시는 태어나지 않을 것 같아요. 아버지가 가죽을 취급하는 피혁방을 크게 했어요. 아버지는 다석을 위해 적선동에 솜공장을 차려주셨어요. 아버지 3년상을 치르고 나서 가게를 팔아 북한산 밑 구기동 농장으로 이사했습니다. 피혁방과 솜공장을 할 적에 ‘이렇게 수를 부리면 돈이 좀더 벌린다’라는 생각이 있었다고 합니다. 사람이 정직하게 사는 법은 농사밖에 없다고 했죠. 그때만 해도 대학을 나오면 자동적으로 좋은 자리를 차지했어요. 그리고 배운 사람들이 어리숙한 사람들을 등쳐 먹기 일쑤였죠. 그래서 상당히 경제적 여유가 있었음에도 아들 셋 다 고등학교까지 보내고 대학 공부를 안 시켰어요. 그리고 내 아들, 내 제자들은 ‘장가가지 말라’ ‘대학 가지 말라’ ‘오로지 농사를 지어라’하는 세 가지 유언을 남겼죠.” 정양모 신부(오른쪽)을 자택에서 인터뷰하는 황호택 고문. -다석은 종로 상인이던 아버지로부터 많은 재산을 상속받았는데요. 그런데 다석이 자식들에겐 왜 그렇게 했을까요? “부자인 선대에서 물려받은 토지가 상당 부분 있었어요. 소작인들이 찾아와서 생활이 어렵다고 하니 공짜로 땅을 다 넘겨주었어요. 다석은 ‘대학 나오지 말라’ ‘관공서에 취직할 생각하지 말라’ ‘농사지어라’라고 했죠. 그런데 첫째와 셋째는 아버지 말을 안 들었습니다. 첫째는 미국으로, 셋째는 일본으로 이민 갔죠. 90세가 넘을 때까지 거기서 살다가 몇 년 전에 다 죽었습니다. 첫째 셋째 아들은 아버지를 이해하지 못한 거죠. 아버지 장례식에 오지 않았습니다. 그렇지만 한국에서 오는 지인들을 만나면 ‘우리 아버지가 특이한 분인데 어떻게 생각하느냐’ ‘부귀영화를 멀리 했지만 대단히 생각이 고귀한 분’이라는 말을 했답니다. 둘째 아들이 가장 오래 살았습니다. 둘째 아들이 다석학회 연구 활동에 보태 쓰라고 돈을 보낸 적도 있습니다. 미국 아들과 일본 아들도 둘째 아들을 통해 아버지 연구를 위해 쓰라며 돈을 보내주었습니다. 큰돈은 아니지만 가족들의 돈으로 다석학회를 운영한다고 보면 맞습니다. 둘째 아들이 아버지의 뜻을 따라 농사를 짓겠다고 했지만 이미 소작인들에게 땅을 다 나눠주어서 농사 지을 땅이 없는 거예요. 그래서 강원도 화전민 땅에 가서 밭을 일구고 그 옆에 삼형제와 아버지, 어머니가 묻혀있습니다. 부인 목포댁이 다석의 괴팍한 뜻을 다 따랐지만, 두 가지에선 대들었다고 합니다. 아이들이 모두 서울에서 경기고 휘문고 나와서 출중한 데다가 대학 공부시킬 돈이 있는데도, 대학 가면 틀림없이 아랫사람을 짓밟을 가능성이 크다며 안 보냈거든요. 자녀교육을 놓고 목포댁이 다석과 대판 싸웠다고 해요. 다석이 천안 광덕에 있는 땅을 소작인에게 거저 주다시피 했지요. 목포댁은 ‘자식들 농사지으라고 해놓고 땅을 다 남 줘버리면 우리 아들은 어떻게 하느냐’고 불만을 토로한 거죠.” 인터뷰어가 “다석은 세속을 초월한 사람”이라고 거들자 정 신부는 “다석은 출세, 돈벌이, 공명심, 세 가지 욕심을 다 끊은 분”이라고 말했다. -다석과 함석헌 선생의 관계에 대해서도 많은 이야기가 있습니다. 함석헌 선생을 통해 다석을 알게 된 분들이 많지요. 그런가 하면 다석과 함석헌 이 두 분을 모두 따르는 사람도 있고, 그 중 한 분을 더 따르는 사람도 있습니다. 두 분에 대한 평가는 어떤지요? “두 분 다 위대하고. 두 분 다 기이한 면이 있죠. 다석이 오산학교 교장 그만두고 떠날 때 ‘내가 이곳에 온 것은 자네 하나를 만나려는 것인가 봐’라고 할 정도로 제자 함석헌을 애지중지했지요. 함 선생에 대해 우리는 듣기 좋게 ‘실덕(失德)’이라고 말합니다. 성천 유달영 선생한테 자세한 이야기를 들었습니다. 성천도 다석의 제자 중 한 분입니다. 함 선생이 민주화 운동을 하기 전에도 반반한 여자만 보면 가만히 두지 않았다는 겁니다. 다석 일지에 보면 아마 50번 정도 제자를 나무라는 이야기가 나와요. 독한 표현은 안 나와요. 함석헌이라고 이름도 잘 안 나옵니다. ‘함’이라고만 나오죠. 제자 이름을 최대한 노출 안 시키려고 하면서도 새벽 3시에 일어났을 적에 ‘그도 일어났을까’ ‘내가 저를 생각하듯이 저도 나를 생각할까’라고 생각하죠. 제자가 괘씸하지만 잊을 수 없었어요. 함석헌 선생이 등장하는 시조가 50편 이상 나오지 않을까 합니다. 아주 많습니다. 곰곰이 들여다보면 함석헌을 그리워하는 시조라는 것을 알 수 있어요. 그 사정을 잘 아는 성천(유달영)이 ‘함석헌이 자꾸만 여자를 탐하는 것은 병적이다. 정상적인 사람은 그렇지 않다’고 했어요. 정신과 의사에게 보내서 치료를 받게 해야 했는데 우리가 손가락질만 했다'고 후회하는 말을 했습니다. 안타까운 이야기죠. 나처럼 자세히 아는 사람이 많지 않을 것입니다. 나는 다석 일지를 통독했지요. 다석을 존경하는 사람, 제자 함석헌을 존경하는 사람, 둘 다 존경하는 사람이 있을 텐데요. 위대한 민주운동가 함석헌을 공개적으로 나무란 다석이 옳지 않다고 하는 사람도 있고요. 제각각입니다.” 조카뻘 되는 먼 친척이 1980년대 초에 함 선생의 여자관계를 폭로한 책을 안전기획부의 지원을 받아 발간한 적이 있다. 함 선생의 제자인 김용준 전 고려대 교수는 2005년 11월호 <신동아> ‘황호택이 만난 사람’ 인터뷰에서 그 책에 ‘따라다니는 여자는 모두 건드리는 것으로 묘사돼 있다’는 질문을 던지자 “함 선생님을 접해보면 알지, 어떻게 따라다니는 여자를 전부 건드려요”고 반론을 폈다. -함 선생의 여자관계에 대한 팩트는 어느 쪽이 맞는가요. “내가 성천 선생님에게 듣기로는 안기부에서 터뜨린 것이 사실이라고 합니다. 민주화 운동을 포기 안 하면 여성 행각 다 폭로하겠다고 했데요.” 인터뷰어가 “안기부가 협박을 한 거군요”라고 묻자 정 신부는 “네. 없던 사실이 아니라 실제로 여성편력이 화려한 것을 찾아낸 것이죠”라고 답했다. “함 선생에게 ‘민주화운동을 그만두지 않으면 여자관계를 폭로해 만천하의 웃음거리로 만들겠다’고 했답니다. 함 선생은 안기부의 협박을 받고 고민하다가 ‘폭로하라’고 했답니다. 내가 다석의 제자이고 함 선생과도 아주 가까운 성천 선생한테 직접 들었습니다.” 다석 연구와 대중화의 장애물은 그가 쓰는 단어의 난해성(難解性)이다. 훈민정음에도 없는 글자를 새로 만들고 소리글자인 한글을 뜻글자로 활용해 이해하기가 어렵다. -다석 낱말사전은 박영호 선생과 함께 편찬 작업을 하고 있다고 들었습니다. ”아니에요. 박영호 선생한테 완전히 맡겼습니다. 종로2가 YMCA 회관에서 한 강의 1년치를 속기사가 기록했습니다. 아주 악필(惡筆)이에요. 그것을 그냥 읽을 수가 없어서 다석학회에서 고쳐 쓰는데 꼬박 1년이 걸렸어요. 그러고 난 다음에 박영호 선생에게 부탁했습니다. '선생도 연세가 높고, 나도 나이가 지긋하니 우리가 아니면 앞으로 할 사람이 없을 것 같습니다.' 박영호 선생은 다석 낱말사전 하고, 나는 다석 시조 2500수를 맡았지요. 나는 일을 마쳐서 금년 말에 책이 나오기를 기다리고 있죠. 이 책이 나오면 석 박사 공부하는 사람들은 더 편해지겠죠. 이제 한시를 다루는 분이 나와야 하겠습니다. 대만문화대학에서 중국문학박사를 하신 분에게 한시를 맡아달라고 말해보았는데, 중국 사람들이 쓰는 한문과 뜻이 상당히 다르다는 것입니다. 문법도 다르고. 도저히 접근을 못 하겠다고 합니다.” 파티마의 성모 프란체스코 수녀원에서 수녀들과 함께 한 정양모 신부. -서강대 재직시절 예수회와 갈등으로 학교를 떠나셨다면서요? “서강대가 예수회 재단입니다. 예수회수도원 원장, 총장, 이사장, 세 우두머리가 다 예수회원이에요. 서강대학교에서 종교학과를 세우고 난 뒤에 강의계획표를 짜다 보니 박사 학위를 가진 교수가 부족했어요. 예수회원 교수 중 한 명을 제외하고는 박사학위가 없던 사람들입니다. 그래서 나와 서공석 신부, 장익 신부를 불렀어요. 나는 서강대에서 1998년부터 20여년간 근무했어요. 예수회는 그동안 젊은 예수회원들을 외국으로 보내서 박사를 많이 배출했죠. 그러니까 자기네 사람을 쓰고 싶었겠죠. 예수회 재단에서 나와 서공석 신부한테 나가주면 좋겠다고 했죠. 정교수에게 정년을 3년 앞두고 나가 달라는 것은 법적으로 절대 안 될 일이죠. 그쪽에서 나가주기를 간절히 원했지만 내가 법원으로 가져가면 승소하지요. 그러나 천주교 신부가 교수 자리를 두고 법원에서 다툰다는 것이 얼마나 꼴사나운 일이 되겠어요. 정나미가 떨어졌죠. 예수회에서 나를 배척하는 구나 하는 생각이 들었어요. 그래서 법원에 안 가고 사표를 쓰고 나왔어요. 나와서 집에서 1년 정도 쉬고 있는데 성공회대학 이재정 총장이 교파가 다른 데도 나를 교수로 불러줘서 정년퇴직까지 잘 지냈어요. 아마 한국종교 역사상 타교파 대학에 가서 교편을 잡은 사람은 나 혼자일 겁니다. 앞으로도 좀처럼 나오지 않을 거예요.” -이번에 나오는 다석 시조풀이 책에 붙인 다석 연보(年譜)를 만드는데 공을 들였다고 들었습니다. “다석이 잘 안 알려진 분이거든요. 전기로 쓰자면 너무 기니까 연보로 쓴 것이죠. 연보 가운데 가장 감동적인 것은 끝부분 ‘출가(出家)하고 임종’이지요. 그분이 87세가 되었을 적에 출가한 적이 있잖아요. 예수님과 톨스토이 두 분 다 객사(客死)했죠 .” 인터뷰어가 여기서 예수는 객사가 아니라 사형당한 거라고 끼어들자 정 신부는 “집안에서 안 죽으면 객사지요”라고 받았다. “두 분이 모두 객사를 했는데, 어떻게 내가 집에서 편하게 죽을 수가 있는가. 그래서 민증(신분증)을 주머니에 넣고 소나무 숲을 찾아간 거예요. 예수님과 톨스토이의 중생을 생각하며 객사 결심을 한 거라고 생각합니다. 91세로 돌아가셨잖아요. 둘째 아들에게서 딸만 넷이 태어났어요. 다석을 추모하는 모임이 성천문화재단에서 매년 있는데 둘째 아들의 둘째 딸 유희원이 꼭 대표로 참석합니다. 둘째 아들과 며느리가 다석의 임종을 지켜봤어요. 3년 동안 말이 없으셨는데 숨을 몰아쉬다 말고 “아들에게 내 몸을 일으켜 다오”라고 했습니다. 아들이 상반신을 일으켜 주니까 한마디 말도 없이 묵언하던 분이 전력을 다해 ‘아바디’라고 큰 소리를 지르며 돌아가시더라. 하느님에 대한 그리움이 사무쳤다고 해야 할까. 왜 아버지라고 하지 않고 ‘아바디’라고 평안도 말씀을 하셨을까. 김흥호 박영호 선생, 두 분의 풀이가 조금 달라요. 박영호 선생은 ‘아 밝으신 분이여 디디고 서시오’라는 뜻으로 아바디라고 했다는 것입니다. 기록에는 안 남아있어요. 저도 박영호의 뿌리죠. 다석은 ‘내가 죽으면 관을 사지 말아라. 화장터로 가져 가거라”고 했지만 후손들이 유언을 들어주지 않았죠. 화장 대신에 토장을 해서 세 번 옮겼어요. 화장하라는 유언을 안 들어준 게 잘 됐다고 제자들이 말합니다. 선생님 묻혀 있는 곳에 제자들이 참배를 가거든요. 화장해서 뿌렸으면 갈 데가 없었을 거예요. 제자들은 장례식 때 다석의 유언을 지켜야 한다고 했지만 둘째 아들이 안된다고 했습니다. 그렇게 해서 묘소가 남아있게 됐죠. 기일(忌日)에 제자들이 모여 참배할 수 있다는 것만 해도 조그만 뜻이 있겠다 싶어요." 정 신부에게 마지막으로 “다석을 어떤 분이라고 한 문장으로 정리할 수 있느냐”고 묻자 “동방의 큰 스승”이라는 말로 인터뷰를 마무리했다. “이분도 참 외로운 분이었잖아요. 스승이 전혀 없고. 하루 종일 성경 한 구절, 어느 한 단락 물어볼 곳이 없고 참고서가 없으니 혼자 명상을 할 수밖에 없었죠. 항상 명상에 빠져 있던 분이시죠.” 인터뷰를 끝내고 정 신부는 인근의 단골 추어탕 집으로 안내했다. 정 신부는 추어탕 대신에 미꾸라지 튀김을 주문했고 나도 따라갔다. 함께 간 여성 두명(인턴기자와 영상팀 AD)은 처음에는 다른 음식을 찾다가 추어탕으로 돌아왔다. 남의 이야기들 듣는 직업을 가진 사람은 뭐든지 맛있게 잘 먹어야 한다. <인터뷰어=황호택 논설고문·정리 이주영 인턴기자>2021-05-05 16:29:26 문재인 대통령이 맛본 인생의 쓴맛은문재인 대통령이 29일 오후 광주광역시 광산구 광주글로벌모터스에서 열린 준공 기념행사에서 근로자와 대화를 하고 있다. “저는 제가 살아오면서 인생에서 가장 힘들고 어려웠을 때 경험했던 쓴맛, 그게 제 성장에 큰 도움이 되었던 것 같습니다. 아마 그게 언제냐 이렇게 말씀드려야 될지 모르겠는데 제가 대학 다니다가 유신 반대 시위로 학교에서 제적당하고 구속이 되었었는데 그때 구치소라는 곳을 갔을 때 정말 참 막막했습니다. 그러니까 정상적인 삶에서 어느 날 갑자기 전혀 다른 세상으로 떨어지게 된 것이었는데, 그때 그 막막했던 그 시기의 쓴맛들, 그게 그 뒤에 제가 살아오면서 이제는 무슨 일인들 감당하지 못하겠느냐, 무슨 일이든 다 해낼 수 있다 이런 자신감도 주고 제 성장에 아주 큰 도움이 된 것 같습니다.” 문재인 대통령이 지난달 29일 광주 광산구 빛그린산단 내 광주글로벌모터스(GGM) 공장 준공식에 참석해 GGM 사원 6명과의 간담회 중에 나온 발언이다. 문 대통령은 경희대 재학 시절 박정희 전 대통령의 장기 집권 계획에 반대하는 시위를 하다 구속됐었다. 입사 당시 인공지능(AI) 역량 면접을 받으면서 “살아오면서 가장 성장에 도움이 됐던 경험이 무엇이냐”는 질문을 받았다는 한 직원이 문 대통령에게도 똑같은 질문을 하자 이같이 답변했다. GGM 공장은 현재까지 385명의 직원을 채용했는데, 이들은 인공지능(AI) 역량면접을 거쳐 입사했다. 예상치 못한 답변에 사회자가 “지금 답변은 AI도 미처 예상 못 했을 것”이라고 말했다. 문 대통령은 이에 “인생은 단맛이 아니라 쓴맛이라고 생각한다”면서 “여기 계신 분들은 입사 이전까지 쓴맛을 다 겪으셨을 테니까 앞으로는 이제 단맛만 보시기 바란다”고 격려했다. 문 대통령은 간담회에 앞서 기념 축사에서 더불어민주당 대표 시절을 떠올리며 “광주에서 열렸던 광주형 일자리 모델 토론회에 참석을 했었다”고 회상했다. 문 대통령은 대선 후보 시절부터 강조해 온 지역상생형 일자리를 강조했다. 지역상생형 일자리는 줄어든 임금을 정부·지자체가 주거·문화·복지·보육시설 등 후생 복지비용으로 지원하는 형태다. 문 대통령은 “지난 대선 때 ‘광주형 일자리 모델을 반드시 실현할 뿐 아니라 그것을 전국적으로 확산시키겠다’고 공약했다”면서 “정말 오랜 세월 동안 끈질기게 노력해서 기어코 성공시킨 우리 광주 시민들, 또 우리 광주시 정말 대단하다. 정말 존경하고 감사드린다”고 말했다. 광주형 일자리는 전국 1호 모델이다. 광주지역 노·사·민·정은 4년 반 동안의 노력 끝에 지난 2019년 1월 광주시와 현대자동차가 투자 협약을 맺었다. 문 대통령은 투자협약식에 참석한 이후, 2년 3개월 만에 광주형 일자리 현장인 GGM 공장을 다시 방문했다. 현재 상생협약은 경남 밀양, 대구, 경북 구미, 강원 횡성, 전북 군산, 부산, 전남 신안까지 총 8개 지역에서 체결됐다. 8개 지역을 합하면 직접고용 1만2000명(간접 포함 시 13만명)과 51조1000억원의 투자가 기대된다. GGM은 전국 첫 지역 상생형 일자리 모델이다. 이번에 1998년 삼성자동차 부산공장 준공식 이후 23년 만에 국내에 첫 완성차 공장을 지었다. 자동차 양산 시점은 오는 9월이 목표다. 문 대통령은 “오늘의 성공은 광주의 성공에 그치는 것이 아니다. 광주형 일자리 모델의 성공을 본받아서 방식은 조금씩 다르지만 전국 곳곳에 상생형 일자리가 생겨났고 그것이 우리나라의 새로운 노사관계, 새로운 노사문화를 제시하고 있다”면서 “광주는 대한민국 민주주의의 상징인데, 거기에 더해서 ‘상생’을 상징하는 도시까지 됐다”고 평가했다. 문 대통령은 상생형 일자리와 관련해 “지금 이 순간에도 새로운 상생형 지역일자리 모델을 찾으려는 노력이 전국 각지에서 계속되고 있고 몇 곳은 올해 안 협약체결 목표로 하고 있다”면서 “총 51조원 투자와 13만개 고용창출을 예정하고 있다”고 밝혔다. 또한 “광주형 일자리 정신은 지역균형 뉴딜로도 이어졌다”면서 “지역과 주민 이익 공유에서부터 행정구역의 경계를 뛰어넘는 초광역 협력까지, 다양한 시도가 모색되고 있다”고 설명했다. 문 대통령은 “이제 대한민국은 광주형 일자리 성공을 통해 얻은 자신감으로 함께 더 높이 도약하는 포용혁신국가를 위해 나아갈 것이고, 정부도 적극 뒷받침하겠다”면서 “다양한 지원을 통해 상생형 일자리를 우리 경제의 또 하나의 성공전략으로 키우겠다”고 약속했다.2021-05-01 06:00:00

문재인 대통령이 맛본 인생의 쓴맛은문재인 대통령이 29일 오후 광주광역시 광산구 광주글로벌모터스에서 열린 준공 기념행사에서 근로자와 대화를 하고 있다. “저는 제가 살아오면서 인생에서 가장 힘들고 어려웠을 때 경험했던 쓴맛, 그게 제 성장에 큰 도움이 되었던 것 같습니다. 아마 그게 언제냐 이렇게 말씀드려야 될지 모르겠는데 제가 대학 다니다가 유신 반대 시위로 학교에서 제적당하고 구속이 되었었는데 그때 구치소라는 곳을 갔을 때 정말 참 막막했습니다. 그러니까 정상적인 삶에서 어느 날 갑자기 전혀 다른 세상으로 떨어지게 된 것이었는데, 그때 그 막막했던 그 시기의 쓴맛들, 그게 그 뒤에 제가 살아오면서 이제는 무슨 일인들 감당하지 못하겠느냐, 무슨 일이든 다 해낼 수 있다 이런 자신감도 주고 제 성장에 아주 큰 도움이 된 것 같습니다.” 문재인 대통령이 지난달 29일 광주 광산구 빛그린산단 내 광주글로벌모터스(GGM) 공장 준공식에 참석해 GGM 사원 6명과의 간담회 중에 나온 발언이다. 문 대통령은 경희대 재학 시절 박정희 전 대통령의 장기 집권 계획에 반대하는 시위를 하다 구속됐었다. 입사 당시 인공지능(AI) 역량 면접을 받으면서 “살아오면서 가장 성장에 도움이 됐던 경험이 무엇이냐”는 질문을 받았다는 한 직원이 문 대통령에게도 똑같은 질문을 하자 이같이 답변했다. GGM 공장은 현재까지 385명의 직원을 채용했는데, 이들은 인공지능(AI) 역량면접을 거쳐 입사했다. 예상치 못한 답변에 사회자가 “지금 답변은 AI도 미처 예상 못 했을 것”이라고 말했다. 문 대통령은 이에 “인생은 단맛이 아니라 쓴맛이라고 생각한다”면서 “여기 계신 분들은 입사 이전까지 쓴맛을 다 겪으셨을 테니까 앞으로는 이제 단맛만 보시기 바란다”고 격려했다. 문 대통령은 간담회에 앞서 기념 축사에서 더불어민주당 대표 시절을 떠올리며 “광주에서 열렸던 광주형 일자리 모델 토론회에 참석을 했었다”고 회상했다. 문 대통령은 대선 후보 시절부터 강조해 온 지역상생형 일자리를 강조했다. 지역상생형 일자리는 줄어든 임금을 정부·지자체가 주거·문화·복지·보육시설 등 후생 복지비용으로 지원하는 형태다. 문 대통령은 “지난 대선 때 ‘광주형 일자리 모델을 반드시 실현할 뿐 아니라 그것을 전국적으로 확산시키겠다’고 공약했다”면서 “정말 오랜 세월 동안 끈질기게 노력해서 기어코 성공시킨 우리 광주 시민들, 또 우리 광주시 정말 대단하다. 정말 존경하고 감사드린다”고 말했다. 광주형 일자리는 전국 1호 모델이다. 광주지역 노·사·민·정은 4년 반 동안의 노력 끝에 지난 2019년 1월 광주시와 현대자동차가 투자 협약을 맺었다. 문 대통령은 투자협약식에 참석한 이후, 2년 3개월 만에 광주형 일자리 현장인 GGM 공장을 다시 방문했다. 현재 상생협약은 경남 밀양, 대구, 경북 구미, 강원 횡성, 전북 군산, 부산, 전남 신안까지 총 8개 지역에서 체결됐다. 8개 지역을 합하면 직접고용 1만2000명(간접 포함 시 13만명)과 51조1000억원의 투자가 기대된다. GGM은 전국 첫 지역 상생형 일자리 모델이다. 이번에 1998년 삼성자동차 부산공장 준공식 이후 23년 만에 국내에 첫 완성차 공장을 지었다. 자동차 양산 시점은 오는 9월이 목표다. 문 대통령은 “오늘의 성공은 광주의 성공에 그치는 것이 아니다. 광주형 일자리 모델의 성공을 본받아서 방식은 조금씩 다르지만 전국 곳곳에 상생형 일자리가 생겨났고 그것이 우리나라의 새로운 노사관계, 새로운 노사문화를 제시하고 있다”면서 “광주는 대한민국 민주주의의 상징인데, 거기에 더해서 ‘상생’을 상징하는 도시까지 됐다”고 평가했다. 문 대통령은 상생형 일자리와 관련해 “지금 이 순간에도 새로운 상생형 지역일자리 모델을 찾으려는 노력이 전국 각지에서 계속되고 있고 몇 곳은 올해 안 협약체결 목표로 하고 있다”면서 “총 51조원 투자와 13만개 고용창출을 예정하고 있다”고 밝혔다. 또한 “광주형 일자리 정신은 지역균형 뉴딜로도 이어졌다”면서 “지역과 주민 이익 공유에서부터 행정구역의 경계를 뛰어넘는 초광역 협력까지, 다양한 시도가 모색되고 있다”고 설명했다. 문 대통령은 “이제 대한민국은 광주형 일자리 성공을 통해 얻은 자신감으로 함께 더 높이 도약하는 포용혁신국가를 위해 나아갈 것이고, 정부도 적극 뒷받침하겠다”면서 “다양한 지원을 통해 상생형 일자리를 우리 경제의 또 하나의 성공전략으로 키우겠다”고 약속했다.2021-05-01 06:00:00

---

![[지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 빛고을의 진정한 魂 오방 최흥종(下)](https://image.ajunews.com//content/image/2021/04/21/20210421160011735254_518_323.jpg) [지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 빛고을의 진정한 魂 오방 최흥종(下)“함께 정치하자”는 金九의 청을 사양 우리는 오방을 어떻게 평가할 수 있을까. 오방이 생전에 아들처럼 아꼈다는 고 이영생 전 광주 YMCA 총무(1992년 타계)는 1986년 한 인터뷰에서 이렇게 말했다. “그분은 동해(東海) 물입니다. 지금 나는 그것을(오방을) 말로 표현하려는 어리석음을 저지르고 있는 거예요.…무어라 표현해도 그분을 다 얘기할 수는 없을 겁니다.” 그렇다. 우리 취재팀의 심정이 꼭 그랬다. 선생에 대해 우리가 대체 무슨 말을 할 수 있을까. 2000년 오방 기념사업회가 각계 인사들로부터 추모 기고를 받아 오방을 기리는 문집, 『화광동진의 삶』을 펴냈다. 거기에는 고 리영희 교수도 참여했다. 그는 오방의 일생을 이렇게 요약했다. “해방 이후, 많은 유혹에도 불구하고 속세의 영달, 출세를 거부한다. 노자의 도교에서 불교의 선까지 모든 것을 수렴해서 완전한 성숙한 삶, 노자의 무위의 삶, 예수의 삶, 부처님의 삶과 같았다. 대체로 성 프란치스코와 슈바이처와 간디와 톨스토이, 일본의 가가와 도요히코와 닮은 실천하는 삶이다.”(『화광동진의 삶』) 가가와 도요히코(かがわとよひこ‧1888∼1960년)는 ‘20세기의 성자’ ‘빈민들의 아버지’로 불리는 일본의 목사, 사회운동가다. 시인 신경림(동국대 석좌교수)은 이 문집에서 오방이 영적(靈的) 부가가치를 창출했으며, 우리들에게 그런 부가가치를 창출할 수 있는 영감과 에너지를 주었다고 말했다. 오방 기념관의 최영관 관장(전남대 명예교수)은 취재팀에게 이렇게 회고했다. “대학시절 함석헌 선생을 광주에 모셔서 특강을 듣곤 했는데 함석헌 선생님은 꼭 무등산으로 오방을 뵈러 갔다. 그때마다 ‘형님 저 왔습니다. 절 받으세요.’라며 오방에게 큰절을 올렸다.” 최 관장은 오방을 “참으로 광주가 낳은 위대한 기독교적 선지자였고, 조국을 위해 헌신하신, 민족의 큰 족적을 남기신 지도자”라고 했다. 그런 오방이지만 기독교 내부에선 반드시 긍정적인 시선만이 있었던 것은 아니다. 일각에선 그를 기인, 또는 이단으로 보기도 했다. 이런 인식은 오방이 그의 무게에 비해 한동안 제대로 평가받지 못했던 이유와 무관하지 않다. 차종순은 “일제 치하에서 현실과 타협했던 목사들, 예컨대 신사참배를 하고, 심지어는 일제에 무기까지 헌납했던 목사들이 해방이 되어서도 교권을 잡고 득세한 데 대해 오방은 참을 수 없었던 것이고, 이런 오방을 목사들은 경계하고, 경원시했다”는 것이다. 오방선생이 있어 福받은 광주시민 이 과정에서 초기에 호의적이었던 외국인 선교사들마저 일제의 정치 배제 논리에 순응해 오방과는 거리를 두었다고 한다. 차종순은 “오방이 지향했던 것은 결국 ‘사회적 복음주의’였다”면서 “선교사들이 서구식 예수님을 우리에게 전달했다면 오방은 이를 한국식 예수님, 즉 한국인이 이해할 수 있는 복음적 예수로 재해석해서 우리에게 전달했다”고 말했다. 신학자 김경재(한신대 명예교수)는 2016년 10월 오방 서거 50주년을 기념하는 세미나에서 오방의 일생을 관통한 하나의 사상(신념)을 ‘생명존중’으로 보았다. “생명존중의 핵심은 예수의 아가페적 사랑(love as agape)이다. 아가페적 사랑은 무조건적인 사랑이다. 불완전한 타자가 인격적으로 자기성취와 자기실현을 이루도록 돕는 사랑이다. 나병환자들과 오방 자신의 생명은 분리돼 있지 않다는 동체대비(同體大悲), 생명일체감의 사랑이다. 오방은 아가페적 사랑의 실재성(實在性)을 경험했고 믿었다.” 오방은 생전에 ‘애적 전융성’(愛的轉融性)이란 제목의 한시(漢詩)를 통해 사랑을 이렇게 노래했다. “자기의 손해를 돌보지 않는 사랑이요/남을 사랑하여 새로운 삶을 이루도록 하는 사랑이요/원수를 사랑하고 남을 용서하는 사랑이요/다함이 없이 새롭고 새롭게 사랑하는 사랑”이라고. 김 교수는 오방의 생명존중의 신앙과 삶이 현대인에게 주는 의미로, 다음 네 가지를 들었다. 모든 생명은 서로 의존하며 함께 존재함을 깨달아야하고, ‘신앙생활’이 중요한 게 아니라 ‘생활신앙’이 중요하며, 종교와 교육은 생명의 자기초월적 영원성에 눈을 뜨도록 본연의 사명에 충실해야 하며, 이를 통해 생명존중을 제1가치로 삼는 제4 인류문명의 시대를 열어가야 한다는 것이다. 오방이 우리에게 남기고 간 영원한 가르침이 아닐 수 없다. 광주에 살면서, 매일 무등산을 올려다보고 오방을 생각하고 그의 생명존중의 사랑에 대해 고뇌할 수 있다는 것은 참으로 복(福)이다. 이재호 논설고문 ‧ 박승호 전남취재본부장2021-04-23 06:00:00

[지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 빛고을의 진정한 魂 오방 최흥종(下)“함께 정치하자”는 金九의 청을 사양 우리는 오방을 어떻게 평가할 수 있을까. 오방이 생전에 아들처럼 아꼈다는 고 이영생 전 광주 YMCA 총무(1992년 타계)는 1986년 한 인터뷰에서 이렇게 말했다. “그분은 동해(東海) 물입니다. 지금 나는 그것을(오방을) 말로 표현하려는 어리석음을 저지르고 있는 거예요.…무어라 표현해도 그분을 다 얘기할 수는 없을 겁니다.” 그렇다. 우리 취재팀의 심정이 꼭 그랬다. 선생에 대해 우리가 대체 무슨 말을 할 수 있을까. 2000년 오방 기념사업회가 각계 인사들로부터 추모 기고를 받아 오방을 기리는 문집, 『화광동진의 삶』을 펴냈다. 거기에는 고 리영희 교수도 참여했다. 그는 오방의 일생을 이렇게 요약했다. “해방 이후, 많은 유혹에도 불구하고 속세의 영달, 출세를 거부한다. 노자의 도교에서 불교의 선까지 모든 것을 수렴해서 완전한 성숙한 삶, 노자의 무위의 삶, 예수의 삶, 부처님의 삶과 같았다. 대체로 성 프란치스코와 슈바이처와 간디와 톨스토이, 일본의 가가와 도요히코와 닮은 실천하는 삶이다.”(『화광동진의 삶』) 가가와 도요히코(かがわとよひこ‧1888∼1960년)는 ‘20세기의 성자’ ‘빈민들의 아버지’로 불리는 일본의 목사, 사회운동가다. 시인 신경림(동국대 석좌교수)은 이 문집에서 오방이 영적(靈的) 부가가치를 창출했으며, 우리들에게 그런 부가가치를 창출할 수 있는 영감과 에너지를 주었다고 말했다. 오방 기념관의 최영관 관장(전남대 명예교수)은 취재팀에게 이렇게 회고했다. “대학시절 함석헌 선생을 광주에 모셔서 특강을 듣곤 했는데 함석헌 선생님은 꼭 무등산으로 오방을 뵈러 갔다. 그때마다 ‘형님 저 왔습니다. 절 받으세요.’라며 오방에게 큰절을 올렸다.” 최 관장은 오방을 “참으로 광주가 낳은 위대한 기독교적 선지자였고, 조국을 위해 헌신하신, 민족의 큰 족적을 남기신 지도자”라고 했다. 그런 오방이지만 기독교 내부에선 반드시 긍정적인 시선만이 있었던 것은 아니다. 일각에선 그를 기인, 또는 이단으로 보기도 했다. 이런 인식은 오방이 그의 무게에 비해 한동안 제대로 평가받지 못했던 이유와 무관하지 않다. 차종순은 “일제 치하에서 현실과 타협했던 목사들, 예컨대 신사참배를 하고, 심지어는 일제에 무기까지 헌납했던 목사들이 해방이 되어서도 교권을 잡고 득세한 데 대해 오방은 참을 수 없었던 것이고, 이런 오방을 목사들은 경계하고, 경원시했다”는 것이다. 오방선생이 있어 福받은 광주시민 이 과정에서 초기에 호의적이었던 외국인 선교사들마저 일제의 정치 배제 논리에 순응해 오방과는 거리를 두었다고 한다. 차종순은 “오방이 지향했던 것은 결국 ‘사회적 복음주의’였다”면서 “선교사들이 서구식 예수님을 우리에게 전달했다면 오방은 이를 한국식 예수님, 즉 한국인이 이해할 수 있는 복음적 예수로 재해석해서 우리에게 전달했다”고 말했다. 신학자 김경재(한신대 명예교수)는 2016년 10월 오방 서거 50주년을 기념하는 세미나에서 오방의 일생을 관통한 하나의 사상(신념)을 ‘생명존중’으로 보았다. “생명존중의 핵심은 예수의 아가페적 사랑(love as agape)이다. 아가페적 사랑은 무조건적인 사랑이다. 불완전한 타자가 인격적으로 자기성취와 자기실현을 이루도록 돕는 사랑이다. 나병환자들과 오방 자신의 생명은 분리돼 있지 않다는 동체대비(同體大悲), 생명일체감의 사랑이다. 오방은 아가페적 사랑의 실재성(實在性)을 경험했고 믿었다.” 오방은 생전에 ‘애적 전융성’(愛的轉融性)이란 제목의 한시(漢詩)를 통해 사랑을 이렇게 노래했다. “자기의 손해를 돌보지 않는 사랑이요/남을 사랑하여 새로운 삶을 이루도록 하는 사랑이요/원수를 사랑하고 남을 용서하는 사랑이요/다함이 없이 새롭고 새롭게 사랑하는 사랑”이라고. 김 교수는 오방의 생명존중의 신앙과 삶이 현대인에게 주는 의미로, 다음 네 가지를 들었다. 모든 생명은 서로 의존하며 함께 존재함을 깨달아야하고, ‘신앙생활’이 중요한 게 아니라 ‘생활신앙’이 중요하며, 종교와 교육은 생명의 자기초월적 영원성에 눈을 뜨도록 본연의 사명에 충실해야 하며, 이를 통해 생명존중을 제1가치로 삼는 제4 인류문명의 시대를 열어가야 한다는 것이다. 오방이 우리에게 남기고 간 영원한 가르침이 아닐 수 없다. 광주에 살면서, 매일 무등산을 올려다보고 오방을 생각하고 그의 생명존중의 사랑에 대해 고뇌할 수 있다는 것은 참으로 복(福)이다. 이재호 논설고문 ‧ 박승호 전남취재본부장2021-04-23 06:00:00 자산운용업계 ESG 경영 가속화…조직 신설·글로벌 협의체 가입국내 자산운용사들이 ESG(환경·사회·지배구조) 경영 및 투자 강화에 나서고 있다. 20일 자산운용업계에 따르면 KB자산운용과 삼성자산운용, 삼성액티브자산운용 등은 최근 기후변화 관련 재무정보공개 협의체(TCFD)에 가입했다. TCFD(Task Force on Climate-reated Financial Disclosure)는 기후 변화 관련 정보 공개와 관련 투자 기준을 마련하기 위해 2015년 주요 20개국(G20) 재무장관 및 중앙은행 총재 협의체인 금융안정위원회(FSB) 주도로 창설된 조직이다. 현재 전 세계 1900여개 기업과 단체가 TCFD에 가입했고 국내에서는 34곳이 가입 중이다. KB자산운용은 TCFD 가입과 더불어 내부에 ESG운용위원회도 신설했다. 위원회는 이현승 KB자산운용 대표를 위원장으로 각 운용본부장들로 구성됐다. 위원회는 앞으로 통합 및 자산별 ESG 전략 수립을 비롯해 ESG 투자 성과 분석, 위험 관리 등 운용 프로세스에 대한 의사결정을 담당한다. 특히 상품위원회를 통한 신규 상품 심의에도 관련 요소를 반영해 상품 출시 단계에서부터 ESG 요소를 적극 반영한다는 계획이다. 삼성자산운용도 이달 중 이사회 내에 ESG위원회를 설치해 ESG 경영을 본격화한다는 전략이다. 한화자산운용의 경우, ESG위원회 설치를 위한 정관 변경을 완료하고 이사 3인으로 위원회를 구성했다. 한화자산운용 ESG위원회는 ESG 관련 경영 전략 및 정책 수립, 관련 규정 제·개정, 활동보고서 발간 등을 담당한다. 특히 한화자산운용은 ESG 활동 지원을 위해 지속가능전략실을 간사조직으로 활용하고 ESG 관여 활동 및 의결권 행사, 리서치 및 평가시스템 등 ESG 투자 기반 체계화 및 내재화에 집중한다는 계획이다. 한화자산운용 관계자는 "ESG위원회 설치는 운용업 본연의 투자활동을 넘어 ESG 요인까지 면밀히 살피고 반영해 우리 사회와 투자자의 신뢰 및 기대를 받는 운용사로 발전하기 위한 것"이라고 설명했다.2021-04-21 00:00:00

자산운용업계 ESG 경영 가속화…조직 신설·글로벌 협의체 가입국내 자산운용사들이 ESG(환경·사회·지배구조) 경영 및 투자 강화에 나서고 있다. 20일 자산운용업계에 따르면 KB자산운용과 삼성자산운용, 삼성액티브자산운용 등은 최근 기후변화 관련 재무정보공개 협의체(TCFD)에 가입했다. TCFD(Task Force on Climate-reated Financial Disclosure)는 기후 변화 관련 정보 공개와 관련 투자 기준을 마련하기 위해 2015년 주요 20개국(G20) 재무장관 및 중앙은행 총재 협의체인 금융안정위원회(FSB) 주도로 창설된 조직이다. 현재 전 세계 1900여개 기업과 단체가 TCFD에 가입했고 국내에서는 34곳이 가입 중이다. KB자산운용은 TCFD 가입과 더불어 내부에 ESG운용위원회도 신설했다. 위원회는 이현승 KB자산운용 대표를 위원장으로 각 운용본부장들로 구성됐다. 위원회는 앞으로 통합 및 자산별 ESG 전략 수립을 비롯해 ESG 투자 성과 분석, 위험 관리 등 운용 프로세스에 대한 의사결정을 담당한다. 특히 상품위원회를 통한 신규 상품 심의에도 관련 요소를 반영해 상품 출시 단계에서부터 ESG 요소를 적극 반영한다는 계획이다. 삼성자산운용도 이달 중 이사회 내에 ESG위원회를 설치해 ESG 경영을 본격화한다는 전략이다. 한화자산운용의 경우, ESG위원회 설치를 위한 정관 변경을 완료하고 이사 3인으로 위원회를 구성했다. 한화자산운용 ESG위원회는 ESG 관련 경영 전략 및 정책 수립, 관련 규정 제·개정, 활동보고서 발간 등을 담당한다. 특히 한화자산운용은 ESG 활동 지원을 위해 지속가능전략실을 간사조직으로 활용하고 ESG 관여 활동 및 의결권 행사, 리서치 및 평가시스템 등 ESG 투자 기반 체계화 및 내재화에 집중한다는 계획이다. 한화자산운용 관계자는 "ESG위원회 설치는 운용업 본연의 투자활동을 넘어 ESG 요인까지 면밀히 살피고 반영해 우리 사회와 투자자의 신뢰 및 기대를 받는 운용사로 발전하기 위한 것"이라고 설명했다.2021-04-21 00:00:00![[지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 다섯 가지 욕망을 다 버린 큰 사람 (上)](https://image.ajunews.com//content/image/2021/04/15/20210415101758285725_518_323.jpg) [지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 다섯 가지 욕망을 다 버린 큰 사람 (上)이재호 논설고문 ‧ 박승호 전남취재본부장2021-04-16 05:49:26

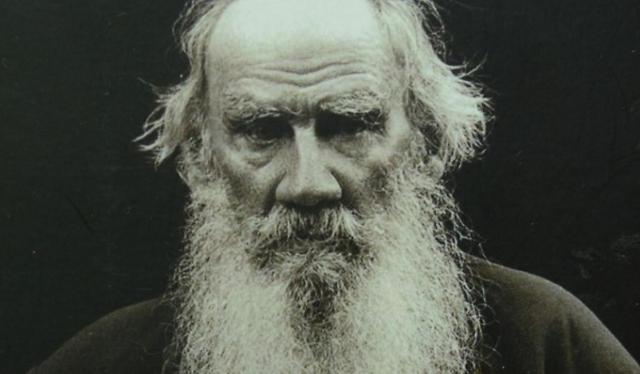

[지역혼의 재발견 - (1) 광주정신] 다섯 가지 욕망을 다 버린 큰 사람 (上)이재호 논설고문 ‧ 박승호 전남취재본부장2021-04-16 05:49:26 말기 암환자가 하루라도 더 살려는 건 다석 알리기 위해서죠독립운동가, 농민운동가이자 교육자였던 성천 유달영(1911~2004)은 함석헌과 함게 다석이 아끼던 제자다. 유달영은 농장이 경부고속도로에 편입되면서 받은 보상금으로 성천문화재단을 설립했다. 그의 좌우명이 호학위공(好學爲公)이다. 열심히 배워서 공익을 위해 봉사하자는 것이다. 다석사상연구회는 매주 화요일 서울 여의도 성천문화재단 사무실에서 공부 모임을 갖고 있다. “2015년 다석 공부를 하려고 한국에 왔거든요. 한국에 나온 동기가 다석 사상을 제대로 공부해 한국에 널리 보급해보겠다는 것이었어요. 20년 전에 처음 접했던 다석 사상의 고향을 찾아온 거죠. 호주에서 심장병으로 쓰러진 적은 있었지만 건강은 좋은 편이었어요. 그런데 한국에 온 지 1년 만에 암이 발생했죠. 내가 참여한 것은 박영호 선생이 성천문화재단에서 다석 강의를 시작한 지 20년 됐을 때였어요. 그런데 강의를 듣는 사람들이 서로 잘 모르고 지내더라고요. 강의를 듣고 각자 헤어지는 거예요. 서로가 인사는 하고 지내야 할 것 아니냐는 생각이 들어 내가 횡적인 조직을 만들었어요. 그게 다석사상연구회가 된 거죠. 박영호 선생의 승낙을 받아 내가 대표가 됐습니다. 지금은 20~30명 회원이 있습니다.” 성천문화재단은 ‘진리의 벗이 되어’라는 계간지(季刊誌)를 발행한다. 141호(2021년 봄호)까지 나왔다. 1년이 4계절이니까 지령(誌齡) 35년을 넘긴 잡지다. 유달영이 살아 있을 때는 매호 ‘성천 단상’이라는 글을 썼다. 촌철살인(寸鐵殺人)의 아포리즘(잠언)이 많다. 이 중에는 ‘훌륭한 신앙은 종교 냄새가 안 난다. 애국심은 반드시 인류애로 연결돼야 한다. 재산 약간 부족한 상태가 최선이다’라는 글도 있다. 최 목사가 좋아하는 글이다. “제자들 중에서도 유달영 선생이 다석 사상 전파를 위해 크게 공헌했습니다. 정신적으로, 물질적으로 양쪽 다요. 다석사상연구회 책임자로 있으면서 성천문화재단에 사용료를 내려고 했더니 유달영 선생이 일절 돈을 받지 말라는 유지(遺志)를 남겼다더군요.” 1961년 쿠데타를 일으켜 정권을 장악한 박정희 소장이 재건국민운동을 시작했다. 먼저 함석헌에게 본부장을 맡아달라고 제의했으나 거절당했다. 유진오를 세웠으나 만족스럽지 않자 유달영에게 요청했다. 유달영은 안 하려고 하다가 다석에게 자문하고 수락했다. 그리고 다석을 중앙위원으로 모셨다. 그러다 유달영이 본부장을 물러나자 다석도 곧바로 그만두었다(다석 전기). 다석은 그 정도로 유달영을 아끼고 신뢰했다. 오른쪽부터 류달영, 함석헌, 다석. “다석의 말씀은 살면서 필요한 것이 아니라 죽을 때 필요하고, 죽고 나서 필요한 것이라는 말을 많이 해요. 그 분은 평생 무릎 꿇고 살았습니다. 평생을 걸어 다녔지요. 평생 일일일식 했습니다. 이런 것은 육신을 영화(靈化)시키기 위한 삶이라고 봐야지 이것을 부수려는 삶이 아닙니다. 그런데 마치 육신을 저버리고 얼나, 참나를 위해 산 것처럼 말하는 것은 오해지요.” 유달영의 저서 <행복의 발견>에는 신문기자가 하늘나라에서 하느님을 인터뷰하면서 “왜 하늘나라에 목사들이 안보이냐”고 물었다는 이야기가 나온다. 하느님이 “그들은 세상에서 쓸데없는 말을 너무 많이 해서 하늘나라에서 못 온 것”이라고 대답했다. 유달영은 ‘가장 비참한 것은 거짓된 교리에 묶여 정신적 노예가 된 것이다. 모든 성자들이 말하는 진리의 말씀은 하늘에 이르는 길”이라고 이 글의 결론을 내린다. -최 목사는 17년간 목회를 했는데요. 일부 목사들이 거짓 교리의 노예가 돼 있다고 할 수 있는지요? “위선자가 많이 모인 집단이 목회 현장이라고 보면 돼요. 성경을 문자 그대로 믿으면 그렇게 될 수밖에 없어요. 구약은 이스라엘 역사 책이죠. 신약은 바울의 기독교 서적입니다. 지금은 다 그렇게 신학대학에서 강의를 합니다.” 한국에 나가 쓸 돈을 벌기 위해 3년 동안 목회를 하지 않고 열심히 노동을 했다. 그렇게 1억5000 만원가량 모았다. 인터뷰어가 “돈 버는 수완이 있는 것 같다”고 하자 최 목사는 “안 쓰고 모은 거죠”라고 답했다. “한국에서 1억5000 만원이면 전원주택을 살 수 있대요. 전원주택 살 돈을 모아 한국에 가자고 해서 왔는데 막상 쉽지 않더라고요. 그래서 인천에 거처를 정했지요. 목회에서 손 딱 떼고 일반인과 똑같이 땀 흘려 돈 벌어서 다석에 올인 하려고 나왔는데, 아시다시피 만만치 않네요. 복부암이 있어서 5일 간격으로 항암 치료를 받습니다. 인천에서 지하철 타고 여기까지 오는데 몇 번 쉬었다가 왔어요. 지하철 광화문역 계단 올라올 때 넘어질 뻔했습니다. 열정은 있는데 뜻대로 안 되네요.” -재미교포들은 이민 초기에 교회에 다니면 물 설고 낯선 땅에서 네트워크가 생겨 정착할 때 크게 도움을 받는다 지요. 호주는 어떻습니까? “내가 목회하던 교회도 교인의 95%가 불법 체류자였어요. 적발되면 바로 잡혀가는 거예요. 관광비자는 6개월 후에 비자가 소멸돼요. 비자가 없는 삶은 범죄자 아닌 범죄자입니다. 무비자로 불안에 떨다가 교회에 나오면 일자리도 생기고 비자 없는 사람들끼리 커뮤니티를 형성할 수 있죠. 40~50명 식구들이 거의 한 가족처럼 지냈지요. 아이들은 일정한 연령이 되면 영주권을 받을 수 있죠. 그럼 영주권을 가진 아들의 부모도 영주권을 받을 수 있죠. 그렇게 정착한 교민들 중에서 변호사 회계사도 나왔습니다. 이들이 한국에 들렀을 때 나를 찾아오면 인생의 보람을 느끼죠.” '이단목사' '해결사 목사' 소리 들으며 다석사상 전파 -호주하면 백호주의가 연상되고 알게 모르게 인종차별도 있다고 하는데요? “인종차별 당하게 행동하는 사람이 인종차별을 받는 것입니다. 호주 사람들은 청소할 때 장갑을 안 껴요. 그런데 한국 청소부들은 장갑을 끼죠. 저도 장갑을 안 끼고 청소했어요. 변기를 맨손으로 닦았죠. 오물이 지저분하다는 생각이 들면 청소하지 말아야죠. 자기들이 지저분하다고 생각하는 것을 맨손으로 거리낌 없이 닦아내면서 존경하는 마음이 생기게 하는 것이죠.” -호주에서 17년간 목회하면서 감동적인 이야기도 많았을 텐 데요? “아이들이 학교에 못 가면 부모가 일터에 간 사이에 방치되잖아요. 그래서 학교 보내는 것이 매우 중요해요. 비자가 없어 학교에 가지 못하는 아이 38명을 내가 학교에 넣어줘 소문이 났어요. 그 아이들이 내 손자, 자식처럼 느껴질 때가 있어요. 그런 아이들이 학교에 못 들어갈 때 학교에 가서 교장을 면담하는 거예요. 처음에 ‘노’ 했던 교장이 내 이야기를 듣고 나서 교감을 불러서 비자가 없는 아이를 ‘오늘부터 수업 받게 하라’고 해요. 이런 경험을 하면 신앙인으로서 보이지 않는 힘이 있구나 하는 생각이 들었어요. 지성이면 감천이라는 말을 체감하겠더라고요.” -호주에서 ‘해결사 목사’ ‘이단 목사’라는 별명이 붙었다면서요? “학교에 도저히 들어갈 수 없는 아이를 학교에 들여보내다 보니까 해결사 목사가 됐죠. 내가 교단에 목사 라이선스만 반납 안 했지 완전히 쫓겨났잖아요. 나를 보는 사람마다 피하는 거예요. 그래서 이단 목사로 소문 난 거죠. 무슨 일이든지 예수를 품고, 진짜 하나님의 전능함을 믿고 목회를 한다면 못할 게 뭐 있겠습니까. 그러나 정의로운 목사는 자기 일에 무능합니다. 자신의 일에는 무능하지만 다른 사람을 위한 일에는 전능해야 해요.” -목사들도 제 머리를 못 깎는 군요. “헌신적으로 목회하는 분들 보세요. 자신의 일은 아무 것도 못해요. 예수님도 마찬가지잖아요. 예수님이 자신을 위해 하신 일이 무엇이 있습니까. 잠자리 하나 정할 데가 없다고 그랬잖아요. 자기가 무능할 적에 능력이 나오는 것이거든요. 나는 지금도 암세포가 이곳저곳으로 옮겨 다녀서 남들이 보면 기적 같겠지만 항암치료를 5년째 받고 있어요.” -다석은 성경에도 해박했지만 노자 장자 공자 맹자 등 동양철학에도 밝았는데요. 다석이 동서양의 종교를 회통(會通)했다는 것은 어떤 의미가 있나요? “불경이나 성경이나 맥이 같아요. 쭉 연구하다 보면 극락이나 천국이나 같은 것이고. 다석은 궁극적으로 한 점에서 만난다고 했죠. 유교도 공자가 천생덕어여(天生德於予) 라고 해서 ’하늘의 덕이 나를 낳았다‘고 했죠. 하늘의 덕이 뭐냐, 성령입니다. 그래서 예수의 성령과 공자의 덕(德)과 석가의 불성(佛性)이나 이름만 다르지 다 똑같습니다. 서로를 보완해야지 싸울 것이 아닙니다. 다석은 동서양의 종교를 회통했습니다. 최제우의 동학사상도 어떤 의미에서는 다석 사상과 일맥상통하죠.” 다석사상연구회가 주최하고 성천문화재단이 후원한 다석 탄긴 기념강좌에서 강연하는 최성무 목사. -최 목사가 웹진 <새길 이야기>에 다석이 ‘51세에 삼각산에서 하늘과 땅과 몸이 하나로 꿰 뚫리는 깨달음의 체험을 하였다. 이때부터 하루 한 끼만 먹고 하루를 일생으로 여기며 살았다’고 썼던데요. 깨달음과 거듭남을 체험해보지 못한 사람들에게는 다석의 삼각산 체험을 어떻게 설명할 수 있습니까? “체험해보지 않은 사람은 몰라요. 나는 목회하기 전에 방탕 생활을 많이 했어요. 술도 많이 먹고…. 그 대가를 지금 받고 있지 않습니까. 그렇게 생활했지만, 신학 공부를 시작하고 서는 어느 순간부터 맥주 한잔도 안 넘어가요. 설명할 수가 없어요. 이건 내 힘, 내 의지대로 안 되는 거예요. 개인적인 이야기지만, 식색(食色)은 내 의지로 끊은 것이 아니라 하나님께서 끊어준 것이라 생각해요. 암 수술을 해서 먹는 밥통을 완전히 없애버렸잖아요. 식에서 완전히 해방됐죠. 내가 방광을 두 차례 수술받아 떼어 냈잖아요. 이후 식색을 내가 인위적으로 못하니까 하나님께서 통째로 없애버리지 않았나 스스로 생각하는데요. 하여간 느낀 사람만이 알 수 있지, 설명을 할 수 없어요. 다석의 삼각산 체험도 다른 사람은 느낄 수 없어요." -다석의 ‘하루살이’를 풀이하면…. “오늘은 어제의 내일이잖아요. 오지 않은 내일이 오늘에 와있는 것이에요. 그러니까 미래와 과거와 오늘이 같이 있는 것이죠. 그래서 영원이라는 것은 현재와 분리된 것이 아니라 일직선 상에 같이 있는 것이에요. 시간적으로 제한된 삶을 사는 것이 아닙니다. 시작이 있다면 끝이 있다는 것이죠. 그런데 시작을 발견한 적이 없잖아요. 그러니까 시작과 끝이라는 것은 인간이 만들어낸 가설이지, 실제로는 영원 속에 살다 영원 속에 가는 것입니다. 그래서 그 영원의 하루가 오늘입니다. 하루를 열심히 잘사는 것이 영원을 잘사는 것이죠.” 하루 하루 열심히 살면 영원을 잘 사는 것 -다석은 평생 무명 베옷 입고 고무신을 신었죠. 그 시대 서민의 전형적인 모습인데요. 그리고 어디든 걸어 다니고… 잣나무 널판에서 자고... 해혼했지요. 기독교인의 모습이라기보다는 고행(苦行)을 하는 불교의 구도자 같습니다. ”잘 지적했는데요. 그런 면을 일반인들이 받아들이기 어렵겠지요. 다석의 신앙과 행동은 우리가 따라하기에는 거리가 있다는 시각이 있어요. 노동자가 일일일식하면 일을 못 하잖아요. 자기 형편에 따라 하는 것이죠. 저도 호주에서 1식을 해봤어요. 청소를 하면서 1식을 했더니 영양실조로 쓰러졌어요. 그래서 멈췄죠. 미련하게 해봤더니, 2년 정도는 그렇게 하겠는데 나중에는 그냥 쓰러지더라고요. 그러나 그분 나름대로의 상황에서 신앙의 형태를 가졌는데, 거기에서 본받을 것은 본받고, 따라 하지 못하는 것에 대해서는 그대로 인정해야 하지 않나 생각합니다. 다석이 늘 무릎 꿇고 경건한 자세로 산 것에 대해서는 본받아야 하지 않을까 하고 생각합니다.” -마태복음 7장 13, 14절에 “좁은 문으로 들어가거라. 멸망에 이르는 문은 크고 또 그 길이 넓어서 그리로 가는 사람이 많지만 생명에 이르는 문은 좁고 또 그 길이 험해서 그리로 찾아 드는 사람이 적다”라고 했는데요. 다석이 말한 얼나를 찾기 위해서는 넓은 문 놓아두고 굳이 좁고 험한 문으로 들어가야 하는지요? “자기 얼나를 찾으려면 탐진치(貪瞋痴)로부터 벗어나야 하거든요. 예수도 석가도, 노자장자도 모두 탐진치에서 벗어나라고 말했는데, 세상 살면서 벗어나기 쉽지 않잖아요. 이런 것을 초월해서 우리가 얼나를 찾는다는 것은 나에게서 탐진치가 완전히 제거된 상태를 의미하는 것이거든요. 그러니까 그게 좁은 문이죠. 물질에서 벗어나는 것은 어느 정도 가능해요. 성적인 것에서 벗어나는 것이 물질보다 어려워요. 명예욕, 과시욕도 쉽게 벗어날 수 있는 게 아니거든요. 그러니까 탐진치에서 완전히 벗어났다고 말하는 건 다석이나 가능하다고 생각합니다. -교회에서 가장 두려워 해야 할 것이 영적 교만이라고 하셨던데, 구체적으로 무엇을 말하나요? “내 신앙이 존중 받으려면 우선 타인의 신앙도 존중해야 합니다. 교회에 나 홀로 충만한 분들이 많아요. 그래서 같은 교인 중에도 믿음이 있다, 없다 하는 분들이 있잖아요. 영적 교만이 지금 교회의 코로나 대응에서도 나타나고 있어요. 믿음은 서로가 다른 대로 나름대로 같다고 봐주고 인정해줘야지, 내 믿음만 옳다 하면 안 됩니다.” 5년째 암과 싸우는 최성무 목사는 다석 공부를 하면서 다석 사상을 알리는 일을 하고 있다. -다석은 공자 석가 노자 다 위대한 스승이라고 인정하면서도 진정한 스승은 예수라고 이야기 했는데요, 다석이 그렇게 말한 이유는 무엇일까요? “다석 사상은 어디까지나 기독교에 바탕을 두었어요. 누구든 제일 먼저 들어온 신앙이 자리매김하게 되어있습니다. 나도 신앙생활 할 적에 통일교에 상당히 매료된 적이 있어요. 고등학교 2,3학년 쯤이었죠. 거기서 탈출하는 게 무척 어려웠어요. 현재는 벗어났다고 생각하지만 가끔 거기에 대한 미련이 조금 있어요. 자리매김한 신앙을 완전히 떠나는 것이 쉽지는 않아요. 다석도 16세 때 입문한 기독교의 정신이 그를 완전히 사로잡고 있었습니다. 신채호 선생 여러 사람이 그에게 불경을 읽어보라고 권유했지요. 다석은 불경과 노장사상의 진리를 공부했지만 기독교 범주 안에 흡수하고 받아들여서 회통한 것입니다. 그렇기 때문에 다석사상의 중심은 어디까지나 기독교가 될 수밖에 없습니다. 예수라는 분과 석가나 노자나 장자를 견줄 수 없는 것은 영적인 문제에 들어가서 해결해야 해요. 예컨대 석가나 노자나 장자나 하나님의 아들로서 자리매김하기에는 왠지 뭔가 그렇잖아요? 다석은 그런 면에서 예수님을 심중에 두지 않았나 그렇게 생각합니다.” -지금 암 투병 중인데…죽음의 그림자가 겁나지 않나요? “처음에 위암이 생겼을 때 병원에서 말기(末期)래요. 다른 곳으로 전이 된 것을 말기라고 해요. 췌장으로 전이되어서 췌장까지 잘랐어요. 췌장을 자르면 물 한잔도 못 먹어요. 췌장액이 나와서 다른 장기를 녹이기 때문에. 그래서 41일간 금식했죠. 항암제를 1년 반 동안 안 맞고 멋대로 있다 보니 간으로 전이됐어요. 그런데 항암치료를 하고 3개월 만에 사라졌어요. 그렇지만 끝나지 않고 방광으로 암이 넘어갔어요. 지금 방광을 두 번 수술했어요. 그러다 보니 장기를 둘러싼 복막에까지 암이 번졌어요. 처음에는 진짜 다석처럼 초월한 마음으로 견뎠는데, 이제 그게 안 되더라고요. 항암주사를 일주일에 두 번 맞은 적도 있지요. 몸이 못 견뎌요. 5일 만에 맞았는데 완전히 내가 아니에요. 어떻게 할 수가 없어요. 죽는 것 외엔 방법이 없어요. 신앙인이 아니라면 자살한 사람들이 이해가 되겠더라고요. 오늘 일주일 만에 외출한 거예요. 이를 악물고 나왔습니다. 다석사상을 전파하기 위해서라도 더 살아야 할 텐데요.” 그는 “다석사상에 구원이 있다는 것을 확신한다. 다석사상연구회 회원들에게 우리가 불쏘시개가 되고 거름이 되자고 말하고 있다”며 인터뷰를 마무리했다. <인터뷰어=황호택 논설고문·정리=이주영 인턴기자>2021-04-07 17:03:15

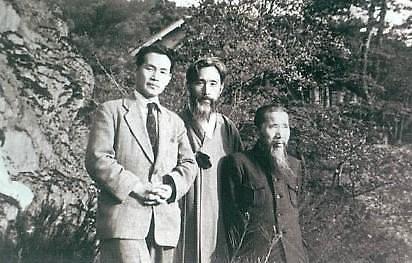

말기 암환자가 하루라도 더 살려는 건 다석 알리기 위해서죠독립운동가, 농민운동가이자 교육자였던 성천 유달영(1911~2004)은 함석헌과 함게 다석이 아끼던 제자다. 유달영은 농장이 경부고속도로에 편입되면서 받은 보상금으로 성천문화재단을 설립했다. 그의 좌우명이 호학위공(好學爲公)이다. 열심히 배워서 공익을 위해 봉사하자는 것이다. 다석사상연구회는 매주 화요일 서울 여의도 성천문화재단 사무실에서 공부 모임을 갖고 있다. “2015년 다석 공부를 하려고 한국에 왔거든요. 한국에 나온 동기가 다석 사상을 제대로 공부해 한국에 널리 보급해보겠다는 것이었어요. 20년 전에 처음 접했던 다석 사상의 고향을 찾아온 거죠. 호주에서 심장병으로 쓰러진 적은 있었지만 건강은 좋은 편이었어요. 그런데 한국에 온 지 1년 만에 암이 발생했죠. 내가 참여한 것은 박영호 선생이 성천문화재단에서 다석 강의를 시작한 지 20년 됐을 때였어요. 그런데 강의를 듣는 사람들이 서로 잘 모르고 지내더라고요. 강의를 듣고 각자 헤어지는 거예요. 서로가 인사는 하고 지내야 할 것 아니냐는 생각이 들어 내가 횡적인 조직을 만들었어요. 그게 다석사상연구회가 된 거죠. 박영호 선생의 승낙을 받아 내가 대표가 됐습니다. 지금은 20~30명 회원이 있습니다.” 성천문화재단은 ‘진리의 벗이 되어’라는 계간지(季刊誌)를 발행한다. 141호(2021년 봄호)까지 나왔다. 1년이 4계절이니까 지령(誌齡) 35년을 넘긴 잡지다. 유달영이 살아 있을 때는 매호 ‘성천 단상’이라는 글을 썼다. 촌철살인(寸鐵殺人)의 아포리즘(잠언)이 많다. 이 중에는 ‘훌륭한 신앙은 종교 냄새가 안 난다. 애국심은 반드시 인류애로 연결돼야 한다. 재산 약간 부족한 상태가 최선이다’라는 글도 있다. 최 목사가 좋아하는 글이다. “제자들 중에서도 유달영 선생이 다석 사상 전파를 위해 크게 공헌했습니다. 정신적으로, 물질적으로 양쪽 다요. 다석사상연구회 책임자로 있으면서 성천문화재단에 사용료를 내려고 했더니 유달영 선생이 일절 돈을 받지 말라는 유지(遺志)를 남겼다더군요.” 1961년 쿠데타를 일으켜 정권을 장악한 박정희 소장이 재건국민운동을 시작했다. 먼저 함석헌에게 본부장을 맡아달라고 제의했으나 거절당했다. 유진오를 세웠으나 만족스럽지 않자 유달영에게 요청했다. 유달영은 안 하려고 하다가 다석에게 자문하고 수락했다. 그리고 다석을 중앙위원으로 모셨다. 그러다 유달영이 본부장을 물러나자 다석도 곧바로 그만두었다(다석 전기). 다석은 그 정도로 유달영을 아끼고 신뢰했다. 오른쪽부터 류달영, 함석헌, 다석. “다석의 말씀은 살면서 필요한 것이 아니라 죽을 때 필요하고, 죽고 나서 필요한 것이라는 말을 많이 해요. 그 분은 평생 무릎 꿇고 살았습니다. 평생을 걸어 다녔지요. 평생 일일일식 했습니다. 이런 것은 육신을 영화(靈化)시키기 위한 삶이라고 봐야지 이것을 부수려는 삶이 아닙니다. 그런데 마치 육신을 저버리고 얼나, 참나를 위해 산 것처럼 말하는 것은 오해지요.” 유달영의 저서 <행복의 발견>에는 신문기자가 하늘나라에서 하느님을 인터뷰하면서 “왜 하늘나라에 목사들이 안보이냐”고 물었다는 이야기가 나온다. 하느님이 “그들은 세상에서 쓸데없는 말을 너무 많이 해서 하늘나라에서 못 온 것”이라고 대답했다. 유달영은 ‘가장 비참한 것은 거짓된 교리에 묶여 정신적 노예가 된 것이다. 모든 성자들이 말하는 진리의 말씀은 하늘에 이르는 길”이라고 이 글의 결론을 내린다. -최 목사는 17년간 목회를 했는데요. 일부 목사들이 거짓 교리의 노예가 돼 있다고 할 수 있는지요? “위선자가 많이 모인 집단이 목회 현장이라고 보면 돼요. 성경을 문자 그대로 믿으면 그렇게 될 수밖에 없어요. 구약은 이스라엘 역사 책이죠. 신약은 바울의 기독교 서적입니다. 지금은 다 그렇게 신학대학에서 강의를 합니다.” 한국에 나가 쓸 돈을 벌기 위해 3년 동안 목회를 하지 않고 열심히 노동을 했다. 그렇게 1억5000 만원가량 모았다. 인터뷰어가 “돈 버는 수완이 있는 것 같다”고 하자 최 목사는 “안 쓰고 모은 거죠”라고 답했다. “한국에서 1억5000 만원이면 전원주택을 살 수 있대요. 전원주택 살 돈을 모아 한국에 가자고 해서 왔는데 막상 쉽지 않더라고요. 그래서 인천에 거처를 정했지요. 목회에서 손 딱 떼고 일반인과 똑같이 땀 흘려 돈 벌어서 다석에 올인 하려고 나왔는데, 아시다시피 만만치 않네요. 복부암이 있어서 5일 간격으로 항암 치료를 받습니다. 인천에서 지하철 타고 여기까지 오는데 몇 번 쉬었다가 왔어요. 지하철 광화문역 계단 올라올 때 넘어질 뻔했습니다. 열정은 있는데 뜻대로 안 되네요.” -재미교포들은 이민 초기에 교회에 다니면 물 설고 낯선 땅에서 네트워크가 생겨 정착할 때 크게 도움을 받는다 지요. 호주는 어떻습니까? “내가 목회하던 교회도 교인의 95%가 불법 체류자였어요. 적발되면 바로 잡혀가는 거예요. 관광비자는 6개월 후에 비자가 소멸돼요. 비자가 없는 삶은 범죄자 아닌 범죄자입니다. 무비자로 불안에 떨다가 교회에 나오면 일자리도 생기고 비자 없는 사람들끼리 커뮤니티를 형성할 수 있죠. 40~50명 식구들이 거의 한 가족처럼 지냈지요. 아이들은 일정한 연령이 되면 영주권을 받을 수 있죠. 그럼 영주권을 가진 아들의 부모도 영주권을 받을 수 있죠. 그렇게 정착한 교민들 중에서 변호사 회계사도 나왔습니다. 이들이 한국에 들렀을 때 나를 찾아오면 인생의 보람을 느끼죠.” '이단목사' '해결사 목사' 소리 들으며 다석사상 전파 -호주하면 백호주의가 연상되고 알게 모르게 인종차별도 있다고 하는데요? “인종차별 당하게 행동하는 사람이 인종차별을 받는 것입니다. 호주 사람들은 청소할 때 장갑을 안 껴요. 그런데 한국 청소부들은 장갑을 끼죠. 저도 장갑을 안 끼고 청소했어요. 변기를 맨손으로 닦았죠. 오물이 지저분하다는 생각이 들면 청소하지 말아야죠. 자기들이 지저분하다고 생각하는 것을 맨손으로 거리낌 없이 닦아내면서 존경하는 마음이 생기게 하는 것이죠.” -호주에서 17년간 목회하면서 감동적인 이야기도 많았을 텐 데요? “아이들이 학교에 못 가면 부모가 일터에 간 사이에 방치되잖아요. 그래서 학교 보내는 것이 매우 중요해요. 비자가 없어 학교에 가지 못하는 아이 38명을 내가 학교에 넣어줘 소문이 났어요. 그 아이들이 내 손자, 자식처럼 느껴질 때가 있어요. 그런 아이들이 학교에 못 들어갈 때 학교에 가서 교장을 면담하는 거예요. 처음에 ‘노’ 했던 교장이 내 이야기를 듣고 나서 교감을 불러서 비자가 없는 아이를 ‘오늘부터 수업 받게 하라’고 해요. 이런 경험을 하면 신앙인으로서 보이지 않는 힘이 있구나 하는 생각이 들었어요. 지성이면 감천이라는 말을 체감하겠더라고요.” -호주에서 ‘해결사 목사’ ‘이단 목사’라는 별명이 붙었다면서요? “학교에 도저히 들어갈 수 없는 아이를 학교에 들여보내다 보니까 해결사 목사가 됐죠. 내가 교단에 목사 라이선스만 반납 안 했지 완전히 쫓겨났잖아요. 나를 보는 사람마다 피하는 거예요. 그래서 이단 목사로 소문 난 거죠. 무슨 일이든지 예수를 품고, 진짜 하나님의 전능함을 믿고 목회를 한다면 못할 게 뭐 있겠습니까. 그러나 정의로운 목사는 자기 일에 무능합니다. 자신의 일에는 무능하지만 다른 사람을 위한 일에는 전능해야 해요.” -목사들도 제 머리를 못 깎는 군요. “헌신적으로 목회하는 분들 보세요. 자신의 일은 아무 것도 못해요. 예수님도 마찬가지잖아요. 예수님이 자신을 위해 하신 일이 무엇이 있습니까. 잠자리 하나 정할 데가 없다고 그랬잖아요. 자기가 무능할 적에 능력이 나오는 것이거든요. 나는 지금도 암세포가 이곳저곳으로 옮겨 다녀서 남들이 보면 기적 같겠지만 항암치료를 5년째 받고 있어요.” -다석은 성경에도 해박했지만 노자 장자 공자 맹자 등 동양철학에도 밝았는데요. 다석이 동서양의 종교를 회통(會通)했다는 것은 어떤 의미가 있나요? “불경이나 성경이나 맥이 같아요. 쭉 연구하다 보면 극락이나 천국이나 같은 것이고. 다석은 궁극적으로 한 점에서 만난다고 했죠. 유교도 공자가 천생덕어여(天生德於予) 라고 해서 ’하늘의 덕이 나를 낳았다‘고 했죠. 하늘의 덕이 뭐냐, 성령입니다. 그래서 예수의 성령과 공자의 덕(德)과 석가의 불성(佛性)이나 이름만 다르지 다 똑같습니다. 서로를 보완해야지 싸울 것이 아닙니다. 다석은 동서양의 종교를 회통했습니다. 최제우의 동학사상도 어떤 의미에서는 다석 사상과 일맥상통하죠.” 다석사상연구회가 주최하고 성천문화재단이 후원한 다석 탄긴 기념강좌에서 강연하는 최성무 목사. -최 목사가 웹진 <새길 이야기>에 다석이 ‘51세에 삼각산에서 하늘과 땅과 몸이 하나로 꿰 뚫리는 깨달음의 체험을 하였다. 이때부터 하루 한 끼만 먹고 하루를 일생으로 여기며 살았다’고 썼던데요. 깨달음과 거듭남을 체험해보지 못한 사람들에게는 다석의 삼각산 체험을 어떻게 설명할 수 있습니까? “체험해보지 않은 사람은 몰라요. 나는 목회하기 전에 방탕 생활을 많이 했어요. 술도 많이 먹고…. 그 대가를 지금 받고 있지 않습니까. 그렇게 생활했지만, 신학 공부를 시작하고 서는 어느 순간부터 맥주 한잔도 안 넘어가요. 설명할 수가 없어요. 이건 내 힘, 내 의지대로 안 되는 거예요. 개인적인 이야기지만, 식색(食色)은 내 의지로 끊은 것이 아니라 하나님께서 끊어준 것이라 생각해요. 암 수술을 해서 먹는 밥통을 완전히 없애버렸잖아요. 식에서 완전히 해방됐죠. 내가 방광을 두 차례 수술받아 떼어 냈잖아요. 이후 식색을 내가 인위적으로 못하니까 하나님께서 통째로 없애버리지 않았나 스스로 생각하는데요. 하여간 느낀 사람만이 알 수 있지, 설명을 할 수 없어요. 다석의 삼각산 체험도 다른 사람은 느낄 수 없어요." -다석의 ‘하루살이’를 풀이하면…. “오늘은 어제의 내일이잖아요. 오지 않은 내일이 오늘에 와있는 것이에요. 그러니까 미래와 과거와 오늘이 같이 있는 것이죠. 그래서 영원이라는 것은 현재와 분리된 것이 아니라 일직선 상에 같이 있는 것이에요. 시간적으로 제한된 삶을 사는 것이 아닙니다. 시작이 있다면 끝이 있다는 것이죠. 그런데 시작을 발견한 적이 없잖아요. 그러니까 시작과 끝이라는 것은 인간이 만들어낸 가설이지, 실제로는 영원 속에 살다 영원 속에 가는 것입니다. 그래서 그 영원의 하루가 오늘입니다. 하루를 열심히 잘사는 것이 영원을 잘사는 것이죠.” 하루 하루 열심히 살면 영원을 잘 사는 것 -다석은 평생 무명 베옷 입고 고무신을 신었죠. 그 시대 서민의 전형적인 모습인데요. 그리고 어디든 걸어 다니고… 잣나무 널판에서 자고... 해혼했지요. 기독교인의 모습이라기보다는 고행(苦行)을 하는 불교의 구도자 같습니다. ”잘 지적했는데요. 그런 면을 일반인들이 받아들이기 어렵겠지요. 다석의 신앙과 행동은 우리가 따라하기에는 거리가 있다는 시각이 있어요. 노동자가 일일일식하면 일을 못 하잖아요. 자기 형편에 따라 하는 것이죠. 저도 호주에서 1식을 해봤어요. 청소를 하면서 1식을 했더니 영양실조로 쓰러졌어요. 그래서 멈췄죠. 미련하게 해봤더니, 2년 정도는 그렇게 하겠는데 나중에는 그냥 쓰러지더라고요. 그러나 그분 나름대로의 상황에서 신앙의 형태를 가졌는데, 거기에서 본받을 것은 본받고, 따라 하지 못하는 것에 대해서는 그대로 인정해야 하지 않나 생각합니다. 다석이 늘 무릎 꿇고 경건한 자세로 산 것에 대해서는 본받아야 하지 않을까 하고 생각합니다.” -마태복음 7장 13, 14절에 “좁은 문으로 들어가거라. 멸망에 이르는 문은 크고 또 그 길이 넓어서 그리로 가는 사람이 많지만 생명에 이르는 문은 좁고 또 그 길이 험해서 그리로 찾아 드는 사람이 적다”라고 했는데요. 다석이 말한 얼나를 찾기 위해서는 넓은 문 놓아두고 굳이 좁고 험한 문으로 들어가야 하는지요? “자기 얼나를 찾으려면 탐진치(貪瞋痴)로부터 벗어나야 하거든요. 예수도 석가도, 노자장자도 모두 탐진치에서 벗어나라고 말했는데, 세상 살면서 벗어나기 쉽지 않잖아요. 이런 것을 초월해서 우리가 얼나를 찾는다는 것은 나에게서 탐진치가 완전히 제거된 상태를 의미하는 것이거든요. 그러니까 그게 좁은 문이죠. 물질에서 벗어나는 것은 어느 정도 가능해요. 성적인 것에서 벗어나는 것이 물질보다 어려워요. 명예욕, 과시욕도 쉽게 벗어날 수 있는 게 아니거든요. 그러니까 탐진치에서 완전히 벗어났다고 말하는 건 다석이나 가능하다고 생각합니다. -교회에서 가장 두려워 해야 할 것이 영적 교만이라고 하셨던데, 구체적으로 무엇을 말하나요? “내 신앙이 존중 받으려면 우선 타인의 신앙도 존중해야 합니다. 교회에 나 홀로 충만한 분들이 많아요. 그래서 같은 교인 중에도 믿음이 있다, 없다 하는 분들이 있잖아요. 영적 교만이 지금 교회의 코로나 대응에서도 나타나고 있어요. 믿음은 서로가 다른 대로 나름대로 같다고 봐주고 인정해줘야지, 내 믿음만 옳다 하면 안 됩니다.” 5년째 암과 싸우는 최성무 목사는 다석 공부를 하면서 다석 사상을 알리는 일을 하고 있다. -다석은 공자 석가 노자 다 위대한 스승이라고 인정하면서도 진정한 스승은 예수라고 이야기 했는데요, 다석이 그렇게 말한 이유는 무엇일까요? “다석 사상은 어디까지나 기독교에 바탕을 두었어요. 누구든 제일 먼저 들어온 신앙이 자리매김하게 되어있습니다. 나도 신앙생활 할 적에 통일교에 상당히 매료된 적이 있어요. 고등학교 2,3학년 쯤이었죠. 거기서 탈출하는 게 무척 어려웠어요. 현재는 벗어났다고 생각하지만 가끔 거기에 대한 미련이 조금 있어요. 자리매김한 신앙을 완전히 떠나는 것이 쉽지는 않아요. 다석도 16세 때 입문한 기독교의 정신이 그를 완전히 사로잡고 있었습니다. 신채호 선생 여러 사람이 그에게 불경을 읽어보라고 권유했지요. 다석은 불경과 노장사상의 진리를 공부했지만 기독교 범주 안에 흡수하고 받아들여서 회통한 것입니다. 그렇기 때문에 다석사상의 중심은 어디까지나 기독교가 될 수밖에 없습니다. 예수라는 분과 석가나 노자나 장자를 견줄 수 없는 것은 영적인 문제에 들어가서 해결해야 해요. 예컨대 석가나 노자나 장자나 하나님의 아들로서 자리매김하기에는 왠지 뭔가 그렇잖아요? 다석은 그런 면에서 예수님을 심중에 두지 않았나 그렇게 생각합니다.” -지금 암 투병 중인데…죽음의 그림자가 겁나지 않나요? “처음에 위암이 생겼을 때 병원에서 말기(末期)래요. 다른 곳으로 전이 된 것을 말기라고 해요. 췌장으로 전이되어서 췌장까지 잘랐어요. 췌장을 자르면 물 한잔도 못 먹어요. 췌장액이 나와서 다른 장기를 녹이기 때문에. 그래서 41일간 금식했죠. 항암제를 1년 반 동안 안 맞고 멋대로 있다 보니 간으로 전이됐어요. 그런데 항암치료를 하고 3개월 만에 사라졌어요. 그렇지만 끝나지 않고 방광으로 암이 넘어갔어요. 지금 방광을 두 번 수술했어요. 그러다 보니 장기를 둘러싼 복막에까지 암이 번졌어요. 처음에는 진짜 다석처럼 초월한 마음으로 견뎠는데, 이제 그게 안 되더라고요. 항암주사를 일주일에 두 번 맞은 적도 있지요. 몸이 못 견뎌요. 5일 만에 맞았는데 완전히 내가 아니에요. 어떻게 할 수가 없어요. 죽는 것 외엔 방법이 없어요. 신앙인이 아니라면 자살한 사람들이 이해가 되겠더라고요. 오늘 일주일 만에 외출한 거예요. 이를 악물고 나왔습니다. 다석사상을 전파하기 위해서라도 더 살아야 할 텐데요.” 그는 “다석사상에 구원이 있다는 것을 확신한다. 다석사상연구회 회원들에게 우리가 불쏘시개가 되고 거름이 되자고 말하고 있다”며 인터뷰를 마무리했다. <인터뷰어=황호택 논설고문·정리=이주영 인턴기자>2021-04-07 17:03:15 美 올해 7% 성장하나?…나날이 높아지는 회복 기대감미국 경제 성장률 전망치가 다시 속속 상향조정되고 있다. 유럽과 남미 등에서 코로나19 3차 확산 우려가 커지고 있지만, 미국의 경우 백신 접종이 속도를 내면서, 집단면역을 다른 지역보다 빨리 이뤄낼 수 있을 것이라는 기대감이 높아지고 있다. 무엇보다 조 바이든 대통령이 밀고 있는 대규모 부양정책은 경제의 회복 속도를 더욱 빠르게 할 것이라는 기대가 높다. 1조 9000억 달러에 달하는 부양책에 더해 3조달러 규모의 인프라 패키지가 논의되면서 기대는 더 커지고 있다. 일단 중앙은행인 연방준비제도(Fed·연준)가 지난 16~17일 연방공개시장위원회(FOMC) 정례회의 뒤 미국의 올해 경제성자률 전망치는 4.2%에서 6.5%로 크게 올렸다. 골드만삭스와 뱅크오브아메리카(BoA)는 올해 미국의 국내총생산(GDP) 기준 성장률을 이전보다 상향 조정한 7.0%로 전망하고 있다. UBS는 올해 성장률을 6.6% 정도로 보고 있다. 미국의 경제성장률이 이들 은행의 예상대로 된다면, 미국의 성장률 중국을 뛰어넘을 수도 있다는 전망이 나온다.2021-03-28 09:35:00