Christian humanism

Christian humanism regards humanist principles like universal human dignity, individual freedom, and the importance of happiness

as essential and principal or even exclusive components of the teachings of Jesus.

Proponents of the term trace the concept to the Renaissance or patristic period,

linking their beliefs to the scholarly movement also called 'humanism'.

Theologians such as Jens Zimmerman make a case for the concept of Christian humanism as a cogent force in the history of Christianity. In Zimmerman's account, Christian humanism as a tradition

emerges from the Christian doctrine that God, in the person of Jesus, became human in order to redeem humanity, and from the further injunction for the participating human collective (the church) to act out the life of Christ.[1]

The term has been criticised, with some noting that it is used to argue for the "exceptionalism" of Christianity, or other understandings of humanism are inauthentic. Some go so far as to say that ideas "common humanity, universal reason, freedom, personhood, human rights, human emancipation and progress, and indeed the very notion of secularity (describing the present saeculum preserved by God until Christ's return) are literally unthinkable without their Christian humanistic roots."[2][3][4]

Definitions[edit]

The initial distinguishing factor between Christian humanism and other varieties of humanism is that Christian humanists not only discussed religious or theological issues in some or all of their works (as did all Renaissance humanists) but according to Charles Nauert,

Christian humanists

기독교 인본주의자는 한편으로는 고전 언어와 문학에 대한 그들의 인본주의적 가르침과 학문, 그리고 다른 한편으로는 성경과 교부들을 포함한 고대 기독교에 대한 연구 사이를 연결했습니다. 기독교 사회의 영적 쇄신과 제도적 개혁을 가져오겠다는 결의로 그들의 학문적 작업(고전적, 성서적, 교부적). 그들의 학문적 노력과 영적, 제도적 쇄신에 대한 갈망 사이의 연결은 "기독교 인본주의자"를 우연히 종교적이게 된 다른 인본주의자들과 구별하는 특정한 특징입니다.

History[edit]

Renaissance[edit]

Origins[edit]

Christian humanism originated towards the end of the 15th century with the early work of figures such as Jakob Wimpfeling, John Colet, and Thomas More and would go on to dominate much of the thought in the first half of the 16th century with the emergence of widely influential Renaissance and humanistic intellectual figures like Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples and especially Erasmus, who would become the greatest scholar of the northern Renaissance.[5] These scholars committed much of their intellectual work to reforming the church and reviving spiritual life through humanist education, and were highly critical of the corruption they saw in the Church and ecclesiastical life. They would combine the greatest morals in the pre-Christian moral philosophers, such as Cicero and Seneca with Christian interpretations deriving from study of the Bible and Church Fathers. The Waldensians have been viewed as a humanistic synthesis of Christianity.[6]

Jakob Wimpfeling[edit]

Although the first humanists did little to orient their intellectual work towards reforming the church and reviving spiritual life through humanist education, the first pioneering signs and practices of this idea emerged with Jakob Wimpfeling (1450–1528), a Renaissance humanist and theologian. Wimpfeling was very critical of ecclesiastical patronage and criticized the moral corruption of many clergymen, however, his timidity stopped him from converting his work from speech to action for fear of controversy. Though he loved reading many of the classics of the writings of classical antiquity, he feared introducing them to mainstream Christianity and sought to use the works of the Latin Church Fathers and a few Christian poets from the Late Roman Empire towards creating a new form of education that would provide church leaders educated in Christian religion, prominent Church authors and a few important classical writings and hence improve Christendom's condition.[7]

John Colet[edit]

John Colet (1467–1519) was another major figure in early Christian humanism, exerting more cultural influence than his older contemporary, Jakob Wimpfeling. Being attracted to Neoplatonic philosophers like Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola and gaining an appreciation for humanistic methods of analyzing texts and developing detailed ideas and principles regarding them, he applied this humanistic method to the epistles of Paul the Apostle. In 1505, he completed his doctorate in theology, and then became a dean at St. Paul's Cathedral. From there, he used his fortune to found near the cathedral St Paul's School for boys. The school was humanistic, both in its teaching of Latin and moral preparation of its students, as well as its recruitment of prominent humanists to recommend and compose new textbooks for it. The best Christian authors were taught, as well as a handful of pagan texts (predominantly Cicero and Virgil), however, Colet's restrictions on the teaching of other classical texts was seen as anti-humanistic and quickly reverted by the school's headmasters. After his death, the school at St. Paul's become an influential humanistic institution. He was very critical of many church leaders.[8] Colet failed to recognize the importance of mastering Greek when it came to the application of humanistic methods to biblical texts, which would be the greatest strength of the work of Erasmus.[9]

Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples[edit]

Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (1453–1536) was, alongside Erasmus, the first of the great Christian humanists to see the importance of integrating Christian learning, in both the patristics and biblical writings, with many of the best intellectual achievements of ancient civilizations and classical thought. He was educated in the University of Paris and began studying Greek under George Hermonymus due to his interest in contemporary cultural changes in Italy. He taught humanities as Paris and, among his earliest scholarly works, was writing an introduction to Aristotle's Metaphysics. He would write many other works on Aristotle and promote the use of direct translations of Aristotle's work from the original Greek rather than the medieval Latin translations that currently existed. His focus then began to shift to the Greek Church Fathers whom he personally considered abler sources for the pedagogy of spiritual life than medieval scholasticism, and his goal became to help revive spiritual life in Europe, retiring in 1508 to focus on precisely this. He began publishing various Latin texts of biblical books such as the Psalms and Pauline epistles and was keen to study textual variations between surviving manuscripts. According to Nauert, these "biblical publications constitute the first major manifestation of the Christian humanism that dominated not only French but also German, Netherlandish, and English humanistic thought through the first half of the sixteenth century."[10][11]

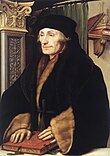

Erasmus[edit]

Erasmus (1466–1536) was the greatest scholar of the northern Renaissance and the most widely influential Christian humanist scholar in history, becoming the most famous scholar in Europe in his day. One of the defining components of his intellectual success was his mastery of Greek. As early as December 1500 while in England, he had written in a letter that his primary motivation for returning to the continent was to pursue studying Greek,[12] and quickly mastered it without a tutor and access to only a small number of Greek texts. In 1505, he translated Euripides's Hecuba, and in 1506, he translated Euripides's Iphigenia in Aulis, both being published in 1506. Erasmus wrote that his motivation in creating these translations was to restore the "science of theology", which had lost its great status because of the medieval scholastics. Two years earlier, he had written that he was going to invest his entire life into the study of scripture through his Greek work;

He had published his Handbook of a Christian Knight (Enchiridion militis christiani) in 1503, writing about his new intellectual direction towards Christ's philosophy, though this text did not gain much popularity. However, when it was published on its own in 1515, it became incredibly popular with 29 Latin editions between 1519–1523 and receiving translations into English, Dutch, German, French, and Spanish. "The secret of its spectacular popular success was its combination of three elements: emphasis on personal spiritual experience rather than external ceremonies, frank criticism of many clergymen for moral corruption ... and insistence that true religion must be expressed in a morally upright life rather than in punctilious observance of the external trappings of religion."[14] The title, Enchiridion, could mean both "dagger" and "handbook", and hence had a double meaning implying its use as a weapon in spiritual warfare.[15] The popularity of Erasmus and his work was further amplified by the success of his literary works like The Praise of Folly, published in 1511, and Colloquies, published in 1518. He also gained incredible success as a textual scholar, interpreting, translating and editing numerous texts of Greek and Roman classics, Church Fathers and the Bible. This textual success began when he discovered and published Lorenzo Valla's Annotations on the New Testament in 1504–1505, and in a single year, in 1516, Erasmus published the first Greek edition of the New Testament, an edition of the works of the Roman philosopher Seneca, and a four-volume edition of St. Jerome's letters. His criticisms of many clergymen and injustices were widely popular and renowned for decades to come, and he succeeded in having truly and fully founded Christian humanism.[14]

Contemporary[edit]

Incarnational humanism is a type of Christian humanism which places central importance on the Incarnation, the belief that Jesus Christ was truly and fully human. In this context, divine revelation from God is seen as untrustworthy precisely because it is exempt from the vagaries of human discourse.

Jens Zimmermann (philosopher) argues that "God's descent into human nature allows the humans ascent to the divine".[16] "If God speaks to us in the language of humanity, then we must interpret Gods speech as we interpret the language of humanity."[17] Incarnational humanism asserts a unification of the secular and the sacred with the goal of a common humanity. This unification is fully realized in the participatory nature of Christian sacraments, particularly the Eucharist. The recognition of this goal requires a necessary difference between the church and the world, where both "spheres are unified in their service of humanity." Critics suggest it is quite wrong to establish a separate theology of the incarnation, and that proponents tend to abstract Jesus from his life and message.

Criticism[edit]

Andrew Copson refers to Christian humanism as a "hybrid term... which some from a Christian background have been attempting to put into currency." Copson argues that attempts to append religious adjectives like Christian to the life stance of humanism are incoherent, saying these have "led to a raft of claims from those identifying with other religious traditions – whether culturally or in convictions – that they too can claim a 'humanism'. The suggestion that has followed – that 'humanism' is something of which there are two types, 'religious humanism' and 'secular humanism', has begun to seriously muddy the conceptual water."[18]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Zimmerman, Jens. "Introduction," in Zimmermann, Jens, ed. Re-Envisioning Christian Humanism. Oxford University Press, 2017, 5.

- ^ Zimmermann, 6-7.

- ^ Croce, Benedetto Croce. My Philosophy and Other Essays on the Moral and Political Problems of Our Time (London: Allen & Unwin, 1949)

- ^ Zimmermann, Jens. Humanism and Religion: A Call for the Renewal of Western Culture. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ^ a b Nauert, Charles, "Rethinking “Christian Humanism” in Mazzocco, Angelo, ed. Interpretations of Renaissance humanism. Brill, 2006, 155-180.

- ^ Bernholz, P.; Streit, M.E.; Vaubel, R. (2012). Political Competition, Innovation and Growth: A Historical Analysis. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 167. ISBN 978-3-642-60324-2. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ Nauert, 170-171.

- ^ Nauert, 171-172.

- ^ Gleason, John B. John Colet. Univ of California Press, 1989, 58-59.

- ^ Rice Jr, Eugene F. "The Humanist Idea of Christian Antiquity: Lefèvre d'Etaples and his Circle." Studies in the Renaissance 9 (1962): 126-160.

- ^ Nauert, 173-174.

- ^ Erasmus to Batt, Orléans, 11 December 1500, Ep. 138 (CWE 1:294–300; Allen 1:320–24)

- ^ Erasmus to Colet, [December?] 1504, Ep. 181 (CWE 2:86–87; Allen 1:404–5)

- ^ a b Nauert, 176-180.

- ^ Anne M. O’Donnell, ‘Rhetoric and Style in Erasmus’ Enchiridion militis Christiani’, Studies in Philology 77/1 (1980), 26.

- ^ "Incarnational Humanism: A Philosophy of Culture for the Church in the World". University of Waterloo. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "The doctrine of the Incarnation By David Gibson". Commonweal. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Copson, Andrew, and Anthony Clifford Grayling, eds. The Wiley Blackwell handbook of humanism. John Wiley & Sons, 2015, 2-3. Chapter: What is Humanism?

Further reading[edit]

- Bequette, John P. Christian Humanism: Creation, Redemption, and Reintegration. University Press of America, 2007.

- Erasmus, Desiderius, and Beatus Rhenanus. Christian Humanism and the Reformation: Selected Writings of Erasmus, with His Life by Beatus Rhenanus and a Biographical Sketch by the Editor. Fordham Univ Press, 1987.

- Jacobs, Alan. The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Oser, Lee. "Christian Humanism and the Radical Middle." Law & Liberty. November 5, 2021. https://lawliberty.org/christian-humanism-and-the-radical-middle/

- Oser, Lee. Christian Humanism in Shakespeare: A Study in Religion and Literature. Catholic University of America Press, 2022.

- Oser, Lee. The Return of Christian Humanism: Chesterton, Eliot, Tolkien, and the Romance of History. University of Missouri Press, 2007.

- Shaw, Joseph et al. Readings in Christian humanism. Fortress Press, 1982.

- Zimmermann, Jens. Humanism and Religion: A Call for the Renewal of Western Culture. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Zimmermann, Jens. Re-Envisioning Christian Humanism. Oxford University Press, 2017.

External links[edit]

- No Christian humanism? Big mistake. Archived 2019-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, Online Catholics, by Peter Fleming. (Accessed 6 May 2012)