Buddhist Christianity

A wide-ranging, searching and partly autobiographical argument that it is reasonable and beneficial to combine definitely Christian and Buddhist commitments.

Synopsis | Reviews (7)

Paperback £14.99 || $24.95

Aug 27, 2010

e-book £6.99 || $9.99

978-1-78099-085-9

Buy e-book

Ross Thompson

Synopsis

It is possible to be a Christian Buddhist in the context of a universal belief that sits fairly lightly on both traditions. Ross Thompson takes especially seriously the aspects of each faith that seem incompatible with the other, no God and no soul in Buddhism, for example, and the need for grace and the historical atonement on the cross in Christianity. Buddhist Christianity can be no bland blend of the tamer aspects of both faiths, but must result from a wrestling of the seeming incompatibles, allowing each faith to shake the other to its very foundations. The author traces his personal journey through which his need for both faiths became painfully apparent. He explores the Buddha and Jesus through their teachings and the varied communities that flow from them, investigating their different understandings of suffering and wrong, self and liberation, meditation and prayer, cosmology and God or not? He concludes with a bold commitment to both faiths.

Double belonging: Buddhism and Christian faith

Paul F. Knitter, author of Without Buddha I Could Not Be a Christian, is Paul Tillich Professor of Theology, World Religions and Culture at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He is a leading advocate of globally responsible interreligious dialogue and author of more than 10 books on the subject. In this, his newest book, he writes very personally, sharing his struggles with his Christian faith while relating how his study of Buddhism -- and his own Zen practice -- has helped him through this struggle.

NCR readers familiar with Buddhism or other Eastern practices and religions will find this book both refreshing and rewarding. It is unusual for a Catholic theologian to write as personally as Knitter has done in this book. I spoke with him recently about his Catholic faith and the Buddhist thought and practice that have entered into his thinking and life as he has worked in the field of interreligious dialogue.

Fox: Do you consider yourself to be a Christian?

Knitter: Oh, I definitely do. I was born a Catholic in Chicago, grew up and entered the seminary. I consider myself to be a Christian, especially in its Roman Catholic form.

Knitter: Oh, I definitely do. I was born a Catholic in Chicago, grew up and entered the seminary. I consider myself to be a Christian, especially in its Roman Catholic form.

Would you say that you’re a Buddhist Catholic or a Catholic Buddhist?

Definitely the noun is Catholic or Christian; the adjective is Buddhist. My primary identity is Christian.

As a Catholic theologian, what is your relationship officially with the church?

I think I’m a pretty reputable member of the Catholic Theological Society of America. I’m a practicing Catholic. My relationship with the church is, as far as I can judge, good.

To be straightforward and honest, I have received some general admonitions from Pope Benedict when he was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. In a book on dealing with other religions, he mentioned me as one of the people who represent a tendency that could easily slip into relativism. I’m working in an area that is quite controversial, namely how Christianity can understand itself in the light of other religions.

In your book you speak of “double belonging.” Just what does that mean?

Double belonging is being talked about more and more now, both in the theological academy and in the area of Christian spirituality. I think it’s the term that is used when more and more people are finding that they can be genuinely nourished by more than one religious tradition, by more than their home tradition or their native tradition.

How widespread is double belonging?

I wouldn’t say it is for general consumption, but in areas of Europe and North America, I think that the number of people who are serious about practicing their faith are finding that some degree of double belonging is becoming more and more a part of their lives.

Why such a broad interest today in Buddhism among Christians?

There’s no one answer. In the book, I quote a friend of mine, Fr. Michael O’Halloran, who is formerly a Carthusian monk and now a priest here in the New York archdiocese. He is also a Zen teacher. Michael once told me that Christianity is long on content but short on method and technique. So I think Buddhism is providing Christians with practices, with techniques, by which they can enter more experientially into the content of what they believe.

What are the needs among Christian believers that you think Buddhism is addressing?

I hope I’m not generalizing here too much, but I think a lot of it has to do with the dissatisfaction that many of us Christians feel with a God who is all out there, a God who is totally other than I, the God who stands outside of me and confronts me. I think we’re searching for ways of realizing the mystery of the divine of God in a way in which it is more a part of our very selves.

I think Christians are searching more for a way of experiencing and understanding God in a unitive way, or what I say in the book is a “non-dual way,” where God becomes a reality that is certainly different than I am, but is part of my very being.

Buddhism does not affirm the existence of God. It has been described as an “atheistic” religion. How can it have significance for a theistic religion like Christianity?

We’ve got to be really careful with how we use the term “atheistic.” Clearly Buddhism does not affirm the existence of a personal God, but I think the better term would be “non-theistic” rather than “atheistic.” It’s not denying God, but if I may put it this way, the Buddha and so much of Buddhism is much more concerned with experiencing ultimate reality rather than defining and naming it.

When you ask a Buddha, “What is it that you are part of when you are enlightened, or when you experience nirvana?” one of the terms or images that are used is sunyata, which means emptiness. That’s not a very good translation but it’s the word they use to identify that ultimate reality is not an entity, a being, but rather it is what they call the interconnectedness of everything. Or as the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh uses the term for ultimate reality, “interbeing.”

Buddhism has helped me to rediscover, to deepen what it means when, in the New Testament -- maybe it’s the only definition of God that we find in the New Testament -- when it says that “God is love.”

I think what Buddhism means by “interbeing” helps me appropriate what in our Christian terminology we mean when we say divine reality is love, and then that sets the stage for me -- and I think for many Christians -- for reappropriating one of our central symbols for God, spirit.

So for me now when I say the word God, what I image, what I feel, thanks to Buddhism, is the interconnecting spirit -- this ever-present spirit, this ever-present, interconnecting energy that is not a person, but is very personal, that this is the mystery that surrounds me, that contains me, and which I am in contact with in the Eucharist, in liturgies, and especially in meditation.

Buddha was enlightened; Jesus was divine. That’s a big difference, isn’t it?

Yes. It’s a big difference. When one looks at, first of all, the language that we Christians use to talk about the mystery of Jesus the Christ, perhaps the two primary words that we use -- or doctrines that we attest to -- are Jesus is Son of God and Jesus is Savior. Now those two terms, Son of God, Savior, are beliefs. These expressions are our attempt to put into words what is the mystery of God.

All of our words are our efforts to try to say in words what can never be fully said in words. In other words, we’re using symbols, we’re using metaphors, we’re using analogies. This goes straight back to St. Thomas Aquinas and to my teacher, Karl Rahner. All of our language is symbolic.

So when the Catholics say that Jesus came to save us, we are not saying just that?

We’re saying something that is very true, something that tries to express what we have experienced, but we can never capture the full reality of it in those words. Again, to use the Buddhist image that is often used, our words are like fingers pointing to the moon -- not the moon itself. Words can never be fully identified with the reality that they are indicating.

You write that Catholics need an eighth sacrament. Explain that.

This has been perhaps one of the key elements that I and many others have learned from Buddhism: the importance of silence. It is in some form of meditation we recognize that the mystery of God is something that cannot be appropriated simply by thought.

This fits into our Catholic sacramental theology. We say that every sacrament contains matter and form. So the matter in the sacrament of silence is our breath, being aware of our breath, being one with our breath, doing nothing else but breathing.

A number of times in the book, you quote Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese monk. You write, echoing Nhat Hanh, that in order to make peace, we have to be peace. Reversing Pope Paul VI’s statement, you state that if we want justice, we have to seek peace. Is that right?

My wife and I spent much of the ’80s and the ’90s working in El Salvador for peace during the war. So we have been activists throughout our lives -- peace activists, social activists. But when I look back at that activism I am aware of how so often our actions were filled with a certain verbal violence.

We had to resist, we had to confront the evil structures. And there are evil structures, but something was missing for me. What was missing was captured in an experience I had back in 1986 or ’87 when I did a Zen retreat with Roshi Bernie Glassman.

I said to him during this retreat that we were going down to El Salvador to try to do something to stop the terrible death squads. He said: “Right, you have to stop the death squads, but you also have to meditate because you will never stop the death squads until you realize your oneness with them.”

That is the experience that Buddhism calls us to, this deep, personal experience of our interconnectedness with all beings, even those whom we have to oppose as oppressors, as perpetrators of evil. We are one with them. This is what Thich Nhat Hanh means when he says that we have to be peace within ourselves. We have to overcome our egos and realize our connectedness with all beings.

You’ve written, “For Buddhists, selfishness is not so much sinful as it is stupid.” Explain.

This is an aspect, I think, that is especially appreciated, or needed, by many Christians. For Buddhism, and I would want to say for Catholicism as well, our fundamental nature is good. Our fundamental nature is the Buddha nature, namely we are part of the interconnected whole, called to be aware of it, and to act out of compassion.

But our problem is that we are not aware of this. Because we’re not aware of this, because we think we are separate individuals rather than part of the interconnected whole, we think we have to protect ourselves. We think we have to gain things in order to establish our identity and, therefore, we act selfishly. We’re acting selfishly, not because we are fallen, not because we are evil in our natures, but because we are ignorant.

You’ve written that in the future, Christians will be mystics or they will not be anything at all. What do you mean?

That is a loose quotation from my teacher, Karl Rahner. What he was getting at is this: There are so many challenges and so many difficulties that we face that unless our identities are based on our own personal experience of God, as part of them, of Christ, as their very being, they are not going to be able to find the strength and the stamina and the wisdom to hang in there.

You’ve written that Buddhism has helped you peer into the mystery beyond death. What about death and life afterwards?

That was perhaps, for me, the most helpful, but maybe the most controversial part of my book. Buddhism tells us that here in this life our true identity, our true happiness, is to move beyond our individuality. I think that resonates with the word, “Unless a grain of wheat genuinely falls into the ground and dies, it will not bear fruit.” Buddhism has led me to look more deeply into what that passage means or what Jesus means when he said, “You will not find yourself unless you lose yourself.”

This has brought me to recognize something that for me seems to be more satisfying, namely that the life that awaits me after I die is going to be an existence that is going to be beyond my individual existence as Paul Knitter. I will live on, but I will not live on probably as Paul Knitter. In other words, our life in the future life after death is a form of existence that is beyond individuality. That doesn’t mean we’re annihilated; that doesn’t mean we don’t exist, but we will exist in a totally transformed, trans-individual existence.

[Thomas C. Fox is NCR editor and can be reached at tfox@ncronline.org.]

===

How the Buddha became a Christian saintJuly 13, 2020 5.58am AEST

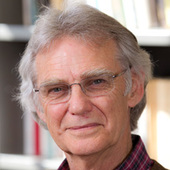

Author

Philip C. Almond

Philip C. Almond

Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Philip C. Almond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.Republish this article

Email

Twitter66

Facebook3.8k

LinkedIn

Print

From the 11th century onwards, the Legend of Barlaam and Josaphat enjoyed a popularity in the medieval West attained perhaps by no other legend. It was available in over 60 versions in the main languages of Europe, the Christian East and Africa. It was most familiar to English leaders from its inclusion in William Caxton’s 1483 translation of the Golden Legend.

Little did European readers know that the story they loved of the life of Saint Josaphat was in fact that of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism.

The ascetic life

According to the legend, there reigned in India a king called Abenner, immersed in the pleasures of the world. When the king had a son, Josaphat, an astrologer predicted he would forsake the world. To forestall this outcome, the king ordered a city to be built for his son from which were excluded poverty, disease, old age and death.

But Josaphat made journeys outside of the city where he encountered, on one occasion, a blind man and a horribly deformed one and, on another occasion, an old man weighed down by illness. He realised the impermanence of all things:

Join 160,000 people who subscribe to free evidence-based news.Get newsletter

No longer is there any sweetness in this transitory life now that I have seen these things […] Gradual and sudden death are in league together.

While experiencing this spiritual crisis, the sage Barlaam from Sri Lanka reached Josaphat and told him of the rejection of worldly pursuits and the acceptance of the Christian ideal of the ascetic life. Prince Josaphat was converted to Christianity and began to practise the ideal of the spiritual life of poverty, simplicity and devotion to God.

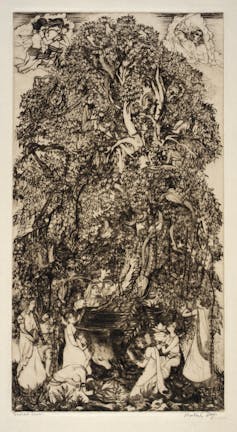

Scenes from the Story of Jehosophat from the Bible. Augsburg, G. Zainer, c.1475. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Paul J. Sachs

To forestall his quest, his father surrounded him with seductive maidens who “tantalised him with every kind of temptation with which they sought to arouse his appetites”.

Josaphat resisted them all.

After the death of his father, Josaphat remained determined to continue his ascetic life and abdicated the throne. He journeyed to Sri Lanka in search of Barlaam. After a quest lasting two years, Josaphat found Barlaam living in the mountains and joined him there in a life of asceticism until his death.

A great saint

Barlaam and Josaphat were included in the calendars of saints in both the Western and Eastern churches. By the 10th century, they were included in the calendars of the Eastern churches, and by the end of the 13th century in those of the Catholic church.

Saints Barlaam and Josaphat, Jacques Callot’s Calendar of Saints, c.17th century. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of William Gray from the collection of Francis Calley Gray, by exchange

In the book we know as The Travels of Marco Polo, published around the year 1300, Marco gave the West its first account of the life of the Buddha. He declared that — were the Buddha a Christian — “he would have been a great saint […] for the good life and pure which he led”.

Read more: Netflix ‘Chinese Game of Thrones’ charts the life of Marco Polo – so who was he?

In 1446, an astute editor of the Travels noticed the similarity. “This is like the life of Saint Iosaphat”, he declared.

It was, however, only in the 19th century the West became aware of Buddhism as a religion in its own right. As a result of editing and translating of the Buddhist scriptures (dating from the first century BCE) from the 1830s onwards, reliable information about the life of the founder of Buddhism began to grow in the West. The Sacred Bodhi Tree. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Chicago Society of Etchers

The Sacred Bodhi Tree. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Chicago Society of Etchers

Then the West came to know the story of the young Indian prince, Gautama, whose father – fearful his son would forsake the world – kept him secluded in his palace. Like Josaphat, Gautama eventually encountered old age, disease and death. And, like Josaphat, he left the palace to live an ascetic life in quest of the meaning of suffering.

After many trials, Gautama sat beneath the Bodhi tree and finally attained enlightenment, thereby becoming a Buddha.

Only in 1869 did this new-found knowledge in the West about the life of the Buddha lead inescapably to the realisation that, in his guise as Saint Josaphat, the Buddha had been a saint in Christendom for some 900 years.

Intimate connections

How did the story of the Buddha become that of Josaphat? The process was long and complicated. Essentially, the story of the Buddha that began in India in the Sanskrit language travelled east to China, then west along the Silk Road where it was influenced by the asceticism of the religion of the Manichees.

It was then transposed into Arabic, Greek and Latin. From these Latin versions it would be translated into various European languages.

Years before the West knew anything about the Buddha, his life and the ascetic ideal which it symbolised were a positive force in the spiritual life of Christians.

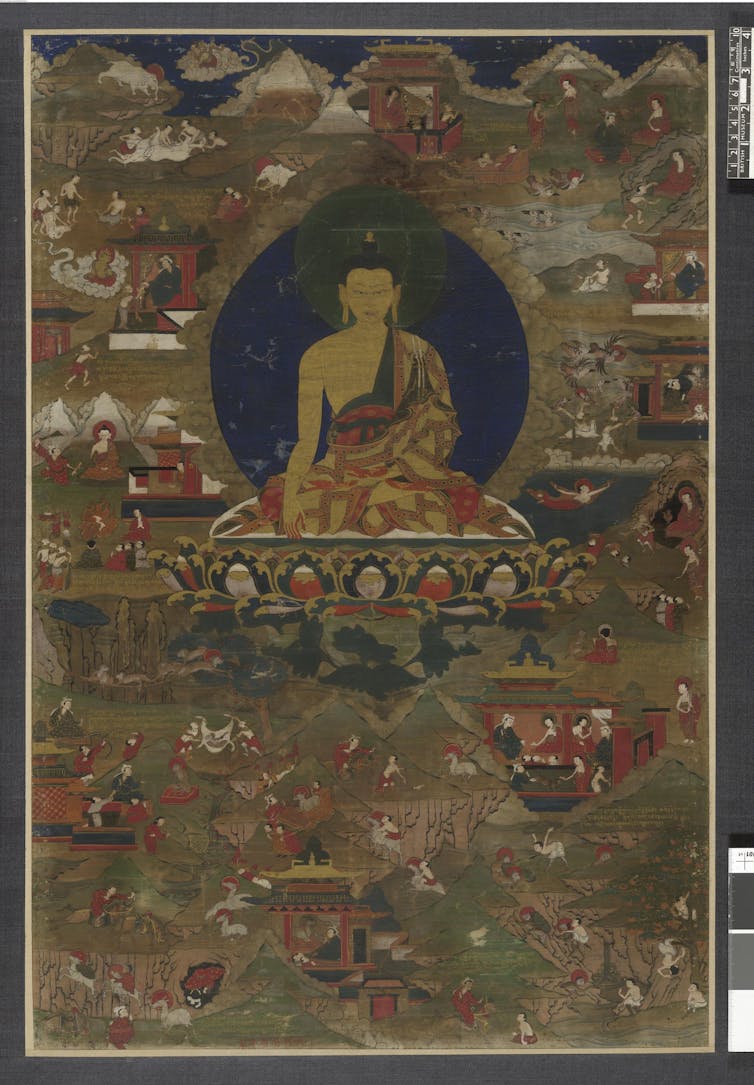

Gautama Buddha seated on a lotus throne, c.1573-1612. © The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

The Legend of Barlaam and Josaphat demonstrates powerfully the intimate connections between Buddhism and Christianity in their commitment to the ascetic, meditative and mystical religious life.

Few Christian saints have a better claim to that title than the Buddha.

In an era where the Buddhist spirituality of “mindfulness” is very much on the Western agenda, we need to be mindful of the long and positive history of the influence of Buddhism on the West. Through the story of Barlaam and Josaphat, Buddhist spirituality has played a significant role in our Western heritage for the last one thousand years.

History

Religion

Christianity

Silk Road

Saints

Buddha

Sainthood

Before you go...

Producing evidence-based journalism comes at a cost. At a time when Australian media is in crisis, The Conversation produces trusted news coverage written by experts and we rely on donors to keep our lights on. If you value us, please show us by becoming a monthly donor.

Give today

Misha Ketchell

Editor

===

CAN A CHRISTIAN BELIEVE IN NO-SELF?

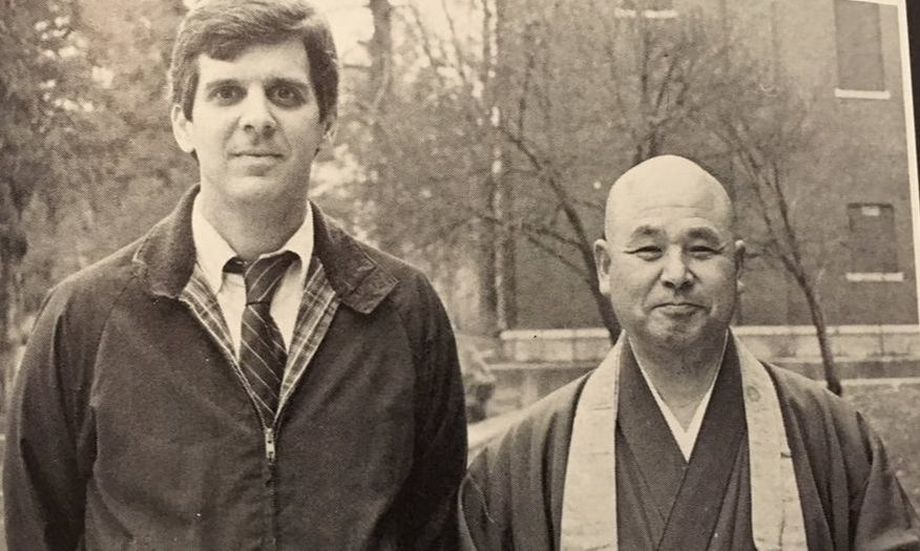

ON BEING ENGLISH TEACHER FOR A ZEN MASTER

Can a Christian be a Buddhist, Too?

Jay McDaniel

In the mornings I would take classes on Christianity under the guidance of gifted seminary professors, all of whom were preparing me to become a minister. And then, in the afternoons, I would serve as the English teacher for a Zen Buddhist monk from Japan, who had recently completed his monastic training in Kyoto, having had the satori (enlightenment) experience with help from his Zen master.

For a young seminarian fresh out of college, my year as an English teacher for this Zen monk – now my good friend - was a very intense year. I would leave morning classes thinking about the self's relation to God as understood in the Gospel of John, deeply steeped in the richness of a Christian path. Then I would visit with a Zen monk in the afternoon, talking about Zen, and wondering if the self and God even existed. He is pictured below.

One day in seminary illustrates the whole year. I remember going to chapel in the morning, before class, and singing Amazing Grace along with my fellow seminarians. I felt enveloped in God’s love. That afternoon I then discussed with my Zen friend the meaning of the well-known koan "What is the sound of one hand clapping?" He explained that there is no rational or formulaic answer, but that there is an "answer" and that it has to do with not having a self separated from the world. He and I were always talking about the Buddhist idea of no-separate-self, or anatman.

I left our discussion wondering if Jesus had a self in the first place, and if God had one as well. Maybe they, too, exemplifiedanatman. Maybe they could hear the sound of one hand clapping because their selves, like that of a good Zen Buddhist, were empty of substance and completed by the world. It seemed to me that the whole year was like this: trying to link the amazing grace of God’s love with the sound of one hand clapping.

Of course this year did not emerge in a vacuum. For me, it emerged as the outcome of a rather deep search, not simply for Christian identity, but for a living Christian faith. I was myself surprised to find that Buddhism might help me find that faith.

I had first become interested in Buddhism during my senior year in college. I was looking for an alternative to a form of fundamentalist Christianity into which I had briefly fallen; and I found that alternative in the writings of the late Catholic writer, Thomas Merton. You will see photos of him on the right. He was a monk living in a monastery in Gethsemane, Kentucky, who wrote voluminously on many topics, including war and peace, social justice, contemplative prayer, mysticism, and Buddhism. Merton’s interest in Buddhism struck a chord in me because I, like he, was drawn to forms of spirituality that emphasize "letting go of words" and "being aware in the present moment." Protestant Christianity often seemed too wordy to me. Buddhism pointed to a world beyond words.

One reason I especially liked Merton was that he was sensitive to the fact that Christianity, too, points to a world beyond words. It points to the world of other living beings who are to be loved on their own terms and for their own sakes, who cannot be reduced to the names we attach to them; and it also points to the world of divine silence as experienced in the depths of contemplative prayer. Merton turned to Buddhism as a way of deepening his own understanding of the wordless, trans-theological dimensions of Christianity, and with his help I did the same.

Under the influence of Merton's writings, then, I began to take courses in world religions during my first year in seminary, even as I also took course in biblical studies, the history of Christianity, and Christian theology. At this stage, my interest in Buddhism was satisfied primarily through books and lectures in these courses. Growing up in a middle-class Protestant setting in Texas, I had not really known a Buddhist, much less a Zen Buddhist, in a personal way. I had known cowboys.

All this changed when I was asked by one of my professors to be the English teacher for the monk from Japan. My professor was a professor of world religions named Margaret Dornish, and I was taking a course on Buddhism under her. Her request, and my acceptance of it, changed my life. The monk’s name was Keido Fukushima, and he was being sent to the United States by his master in Japan to learn English and to learn about America. My assignment was to meet with him every day for one full year, teach him English, and also take him to numerous sites throughout southern California, from malls to monasteries. Indeed, I myself was to be part of the experience for him. In meeting me and getting to know how young people think, he would be meeting an "American." I tried my best to be an “American” for him, but I am sure that I was, at best, a middle-class Texan. I worried, along with Dr. Dornish, that I would be teaching Keido Fukushima to speak English with a Texas accent.

I quickly learned that my student, whom I was told to call Gensho, had already had seven years of English as a student in Japan. I later learned that Gensho means young monk and that I was calling him "young monk" the whole time. This was odd, because he was ten years my senior, but it never seemed to bother him. In any case, he was being sent to the United States, not to learn English, but rather to brush up on English, so that he could return to Japan and field questions from Americans about Zen. Given his facility with the language, our agreement was that I would teach him English by having him explain Zen to me. Thus, we spent hours upon hours talking about Zen and Buddhism.

As soon as we began talking about Zen, he explained to me that the best way to understand Zen is to undertake a daily practice of Zen meditation, or zazen. Under his guidance I did take up that practice, and I have been doing it ever sense. It introduced me to that world beyond words -- the world of pure listening -- that had led me to be interested in Zen in the first place. Twenty years of Zen meditation is at least part of the experience that I bring to this website. The other part is twenty years of teaching Buddhism and Asian religions to college undergraduates.

But Gensho's explanations of Zen did not stop with discussions or with zazen. The wisest teachings he gave me in those days were the gleam in his eye, his ever-present sense of humor, and his kindness. These activities were for me then, and are for me now, living Zen. Dead Zen is what you get in books, and perhaps even books like this. Living Zen is what you get when you are face to face with a Zen person or, still more deeply, with life itself. As Gensho would often say, the ultimate koan is not the question: "What is the sound of one hand clapping?" It is life itself. It is how you respond to what presents itself: the birth of children, the death of loved ones, the caress of your beloved, the beauty of sunsets, the murder of innocents, the laughter of friends, the hunger of the child. When you respond with wisdom and compassion in the immediacy of the moment, you have become living Zen. Your life is your sermon. You are like the dog and cat in the photo: present in the present moment, true to your Buddha-nature in all its particularity.

With his help, then, I came to realize that Zen is not about arriving at another place called nirvana, but rather about arriving at the place where we start -- namely the present moment -- and living freely in the here-and-now of daily life. Zen is among the most down to earth and concrete religions I know. It is very bodily and practical. For this reason I think Zen can enrich the incarnational emphasis of Christianity, which likewise finds the infinite in the finite, the sacred in the ordinary, the word in the enfleshedness of daily life. Living Zen can help Christians enter more deeply into that form of living to which we aspire: life in Christ.

As I was spending my afternoons and many an evening with Gensho, my more conservative friends in seminary worried a little about me. They knew that Zen Buddhists do not often speak of God and that faith in God is not part of the Zen world. And they worried that I myself was falling into a dual religious identity. One of them called it "double religious belonging."

I was not comfortable with this phrase. Even as I felt like I was experiencing two different worlds each day, I did not feel that I belonged to two countries and had two passports. Rather I felt like one person who was receiving nourishment from two intravenous tubes: one the dharma of Buddhism and the other the wisdom of Christ. I borrow this metaphor from a wonderful Zen teacher in the United States, Susan Jion Postal. Intuitively I knew the two medicines were compatible, but I was trying to figure out how they were compatible with my mind. Moreover, I knew that if I had to choose one medicine over another, I would choose Christ. I was not all Buddhist and all Christian, or half Buddhist and half Christian, but rather a Christian influenced by Buddhism. Fortunately, the two fluids did indeed feel compatible and mutually enriching, so I wasn't forced to choose. Each had a healing quality that could add to the other.

What, then, was the healing quality of Christianity? Of course it has a lot to do with God and with the healing power of faith in God. Part of this healing quality can be described if I go into greater detail about the chapel service in seminary, when we sangAmazing Grace. When I sang along with the others, I felt that there was indeed a grace at hand, both in the lyrics and the melody and in the people singing it. We were somehow together in a communion of love, even as we were different persons. I sensed that there is a mysterious and encircling presence -- a sky-like mind -- in which we live and breathe and have our being, and that this mind is amazingly graceful. We can live from this grace and even add to it.

For my part, I felt this grace most vividly, not in ideas learned from books, but in the gifts of personal relationships, in the beauty of the natural world, in the depths of dreams, in hopes for peace, in the silence of the soul, in the eyes of animals, in the mysteries of music, and in acts of lovingkindness. There is something beautiful in our world, even amid its tragedies. For me, this beauty is God. God is the lure toward beauty in the universe, plus more. And God is in the beauty, too. The beauty of the world is God's body.

Admittedly, even in seminary, I did not always envision God as a male deity residing off the planet. Neither did my professors, especially those who were process theologians. With their help I arrived at a way of thinking about God that has made sense to me ever since. They helped me see that the universe is not outside God, like a servant seated far beneath a throne on which sits a king; but rather inside God, like developing embryos are inside a womb, or schools of fish are inside an ocean, or clouds are inside the sky.

My professors called this perspective pan-en-theism: a phrase which was coined in the nineteenth century, and which literally means that everything-is-in-God even as God is more than everything. It seemed to me then and seems to me now that pan-en-theism is closer to the truth of amazing grace. Grace is not something we approach from afar, like a throne on which sits a king, but rather something that is "always already here" as pure gift. Just as the ocean is "always already here" for a fish swimming in it, so grace is "always already here" for human beings. Our task, as humans, is to awaken to what is always already here.

I have said that from a pan-en-theistic perspective God is more than everything added together. This is certainly the case for process theologians. Just as an ocean is more than all the fish swimming in it, so God is more than our experience of God. Imagine a fish swimming off the coast of the Gulf of Mexico in North America, and imagining that he knew everything about the ocean, including what it is like off the coast of New Zealand and South Africa and the Arctic. This fish would be equating its own experience of God with the whole of God.

Unfortunately, this is what I did during my senior year in college when I was a fundamentalist. I was pretty sure that I knew the whole of God and that others who disagreed with me were wrong. And this is why I am so glad to have discovered Thomas Merton, who helped me realize that the divine ocean is always more than our experience of it and we can lie back gently into its waters. From Merton I learned about God the more-ness, and about how silent listening was profound way to be connected with this God.

Oftentimes in seminary before I went to sleep at night, I would pray to the divine more-ness. Not only the contemplative prayer that Thomas Merton describe, but also the more traditional prayer of address that is at the heart of so much lived religion. I would open my heart to the divine ocean and say “Please be with them O Lord” or "I am so sorry, God" or "Thank you, it is so beautiful" or "May all beings be happy." Indeed, in times of sadness, I would also pray the harder prayers, the lamentations and protests, such as "Why did you let this happen?" and "Where are you, anyway?" and "Why have you forsaken me?" These were for me a kind of primal speech of the heart, more like poetry than prose. They were reaching out into the vastness of a mystery beyond my imagination, yet present even in its absence.

At first I felt a little guilty about these harder prayers. I knew that you find this kind of praying in the Bible quite often, in the Psalms for example, but for some reason I thought I was supposed to be nicer to God than the biblical authors. Thankfully, my professors explained that all these ways of praying are authentic if they come from the heart, because the divine ocean is big enough and powerful enough to receive and absorb all doubts, pains, sufferings and even all sins.

How did they know this? Most of them appealed to experience and also to Jesus. In the minds of most of my teachers, Jesus was not a supernatural figure who descended to the earth from above, but rather a man among men whose opened heart revealed a special aspect of God: namely God's open-hearted reception of the world into the divine life, with a tender care that nothing be lost. If we imagine God as an ocean, they said, then let us imagine Jesus as a fish among fish, whose opened heart reveals the Empathy and Eros of ocean itself. Jesus was, as it were, a window to the divine. I liked to think of Jesus as one of those fish with especially shining eyes. You would look into his eyes and see the ocean. Its name was not power or control or fear. Its name was compassion. You could feel this ocean every time you listened to other fish and cared for them. You could feel it when you had compassion for yourself, too. It was a very wide ocean, without boundaries, and somehow people saw it in the eyes of Jesus. Not his alone, of course, but also in the eyes of others.

Of course not all eyes reveal compassion. Some are all about power and control. People with power-hungry eyes have somehow lost sight of their capacities for vulnerable love. Their victims need our special love and care, and our hope that somehow the journey of live continues afterwards, so that their hearts find peace. And those with power-hungry eyes need our love, too. This is a teaching of Buddha and Jesus. We must not draw boundaries around love.

I think that the ocean of compassion is also an ocean of listening. It is affected by everything that happens all the time: omni-vulnerable, like a man on a cross. I had a few friends in seminary, and I have many friends now, who do not believe in prayer. Some of my friends in the college where I teach don't believe there is a divine ocean in the first place. They believe that the great receptacle in which the universe unfolds is an empty space rather than an amazing grace, more like a vacuum than an opened heart. And, of course, they may be right. When it comes to the mystery within which we all swim like fish in the sea, we all see through a glass darkly. No one can grasp the ocean, not even Christians.

Additionally, I have more religious friends who do indeed believe in a divine mystery of sorts, but who do not believe it receives prayers. They see the mystery more like an energy or force which can act upon things, but which cannot be acted upon. It has the power to give, but not to receive. Our task, they say, is to do the will of God, they say, cognizant that God does not need us in any way. For these friends, God is more like the male deity residing off the planet than an ocean of compassion. He stands above the earth, watching from time to time, and intervening from time to time, but he would do just fine if the earth and the whole universe ceased to exist.

For my part, I have no objection to other people imagining God as a male deity residing off the planet. I think we need many different images of God in our imaginations, and that this image is one among many that can help us. I have met people whose lives have been empowered to deal with great suffering, with great courage, through this image of God. But I do indeed have a problem with people who imagine this male deity as having the power to give but not to receive; the power to issue commands but not to empathize; the power to act in the world, but not to be acted upon by the world. When God is imagined in this way, we have, as the philosopher Whitehead once put it, rendered unto God that which belongs to Caesar.

I'm with Whitehead. A God who lacks the power to receive, who doesn't need the world in any way, is too monarchical. He is a lot like Caesar but not much like Christ. When I say "God" in this column I mean the Christ-like God as opposed to the Caesar-like God. I mean the God who is present to each living being on our planet and throughout the universe with a tender care that nothing be lost. I mean the God who is filled by the universe, just as an embryo fills a womb, or stars fill a dark and starlit sky, or fish fill the sea. I mean the God whose face is compassion not power, whose body is the world itself. I mean the God who is an ocean. The God whom Christians see revealed, but not exhausted, in the healing ministry of Jesus.

Faith in God is trust in the availability of fresh possibilities. And life in God lies in being present to each situation in a kindly way, open to surprise, honest about suffering, and seeking wisdom for daily life. I saw this kind of faith in "Gensho." He did not have an image of God in whom he placed that faith. When God becomes an ocean, we must sit loose with images, too, lest we make idols of them. Still we can have faith in something more, maybe even someone more: someone who listens and seeks our well-being. This is a faith to which I am drawn, moment by moment, as I try to walk with Christ, with help from Zen.