Peace Testimony - Wikipedia

Peace Testimony

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

The Peaceable Kingdom (c. 1834) by Edward Hicks

Peace testimony, or testimony against war, is a shorthand description of the action generally taken by members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) for peace and against participation in war. Like other Quaker testimonies, it is not a "belief", but a description of committed actions, in this case to promote peace, and refrain from and actively oppose participation in war. Quakers' original refusal to bear arms has been broadened to embrace protests and demonstrations in opposition to government policies of war and confrontations with others who bear arms, whatever the reason, in the support of peace and active nonviolence.

Because of this core testimony, the Religious Society of Friends is considered one of the traditional peace churches.

Contents

1General explanation

2Development of Quaker beliefs about peace

3Friends' testimony to peace

4See also

5References

6External links

General explanation[edit]

Quakers in Pennsylvania meeting with Native Americans

Friends' peace testimony is largely derived from beliefs arising from the teachings of Jesus to love one's enemies and Friends' belief in the inner light. Quakers believe that nonviolent confrontation of evil and peaceful reconciliation are always superior to violent measures. Peace testimony does not mean that Quakers engage only in passive resignation; in fact, they often practice passionate activism.

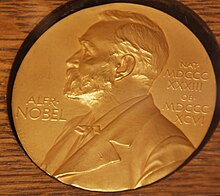

The Peace Testimony is probably the best known testimony of Friends. The belief that violence is wrong has persisted to this day, and many conscientious objectors, advocates of non-violence and anti-war activists are Friends. Because of their peace testimony, Friends are considered as one of the historic peace churches. In 1947 Friends as a worldwide religious group were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, which was accepted by the American Friends Service Committee and the then London Yearly Meeting's Friends Service Committee, now called Britain Yearly Meeting Peace & Social Witness on behalf of all Friends. The Peace Testimony has not always been well received in the world; on many occasions Friends have been imprisoned for refusing to serve in military activities.[citation needed]

Some Friends today regard the Peace Testimony in even a broader sense, refusing to pay the portion of the income tax that goes to fund the military. Yearly Meetings in the United States, Britain and other parts of the world endorse and support these Friends' actions.[1]The Quaker Council for European Affairs campaigns in the European Parliament for the right of conscientious objectors in Europe not to be made to pay for the military. Some do pay the money into peace charities and still get goods seized by bailiffs or money taken from their bank accounts.[citation needed]

In the United States, others pay into an escrow account in the name of the Internal Revenue Service, which the IRS can only access if they give an assurance that the money will only be used for peaceful purposes.[2] Some Yearly meetings in the US run escrow accounts for conscientious objectors, both within and outside the Society.

Many Friends engage in various non-governmental organizations such as Christian Peacemaker Teams serving in some of the most violent areas of the world. Quaker author Howard Brinton, for example, served in the American Friends Service Committee during World War I.

Contents

1General explanation

2Development of Quaker beliefs about peace

3Friends' testimony to peace

4See also

5References

6External links

General explanation[edit]

Quakers in Pennsylvania meeting with Native Americans

Friends' peace testimony is largely derived from beliefs arising from the teachings of Jesus to love one's enemies and Friends' belief in the inner light. Quakers believe that nonviolent confrontation of evil and peaceful reconciliation are always superior to violent measures. Peace testimony does not mean that Quakers engage only in passive resignation; in fact, they often practice passionate activism.

The Peace Testimony is probably the best known testimony of Friends. The belief that violence is wrong has persisted to this day, and many conscientious objectors, advocates of non-violence and anti-war activists are Friends. Because of their peace testimony, Friends are considered as one of the historic peace churches. In 1947 Friends as a worldwide religious group were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, which was accepted by the American Friends Service Committee and the then London Yearly Meeting's Friends Service Committee, now called Britain Yearly Meeting Peace & Social Witness on behalf of all Friends. The Peace Testimony has not always been well received in the world; on many occasions Friends have been imprisoned for refusing to serve in military activities.[citation needed]

Some Friends today regard the Peace Testimony in even a broader sense, refusing to pay the portion of the income tax that goes to fund the military. Yearly Meetings in the United States, Britain and other parts of the world endorse and support these Friends' actions.[1]The Quaker Council for European Affairs campaigns in the European Parliament for the right of conscientious objectors in Europe not to be made to pay for the military. Some do pay the money into peace charities and still get goods seized by bailiffs or money taken from their bank accounts.[citation needed]

In the United States, others pay into an escrow account in the name of the Internal Revenue Service, which the IRS can only access if they give an assurance that the money will only be used for peaceful purposes.[2] Some Yearly meetings in the US run escrow accounts for conscientious objectors, both within and outside the Society.

Many Friends engage in various non-governmental organizations such as Christian Peacemaker Teams serving in some of the most violent areas of the world. Quaker author Howard Brinton, for example, served in the American Friends Service Committee during World War I.

Development of Quaker beliefs about peace[edit]

See also: Christian pacifism

George Fox, perhaps the most influential early Quaker, made a declaration in 1651 that many see as the first declaration of Friends' beliefs on peace: [3]

Following the 1660 Restoration of King Charles II and a clamp-down on religious radical groups such as the Fifth Monarchists,I told [the Commonwealth Commissioners] I lived in the virtue of that life and power that took away the occasion of all wars and I knew from whence all wars did rise, from the lust, according to James's doctrine... I told them I was come into the covenant of peace which was before wars and strifes were.

A number of letters and statements were written this year, as much to remove any suspicion that Friends might have been involved in violent political activity as a desire to make their position clear. Margaret Fell wrote a letter to King Charles II that was co-signed "in unity" by a number of prominent Friends, including Fox:We are a people that follow after those things that make for peace, love, and unity; it is our desire that others' feet may walk in the same, and do deny and bear our testimony against all strife, and wars, and contentions that come from the lusts that war in the members, that war against the soul, which we wait for and watch for in all people, and love and desire the good of all.[4]

The most well-known statement of this belief [5] was stated later that year in a declaration to King Charles II of England in 1660 by George Fox and 11 others. This excerpt is commonly cited:All bloody principles and practices we do utterly deny, with all outward wars, and strife, and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatsoever, and this is our testimony to the whole world. That spirit of Christ by which we are guided is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move unto it; and we do certainly know, and so testify to the world, that the spirit of Christ, which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of this world.[6]

Some Quakers initially opposed this statement because it did not deny use of the sword to the magistrate or ruler of the state.[citation needed] It also contained no prohibition against paying taxes for purposes of war, something that would trouble Friends to the present.

Friends' testimony to peace[edit]

In 1947, the Religious Society of Friends was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The peace testimony of Friends is their best known.[7]

Quakers have engaged in peace testimony by protesting against wars, refusing to serve in armed forces if drafted, seeking conscientious objector status when available, and even to participating in acts of civil disobedience. Not all Quakers embrace this testimony as an absolute; for example, there were Friends that fought in World War I and World War II. Some others were firm Christian pacifists. During extreme circumstances it has been difficult for some Quakers to engage in and uphold this testimony, yet Friends have almost universally been committed to the ideal of peace, even those who have felt the need to compromise on their testimony. Apart from the specific question of war, other ways in which Friends have testified to peace have included vegetarianism and a commitment to restorative justice.

The Religious Society of Friends was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1947. The Nobel Prize was awarded to Friends for Friends' work to relieve suffering and feed many millions of starving people during and after both world wars. The Nobel prize was accepted by the American Friends Service Committee, along with the UK's Friends Service Council on behalf of all Quakers.

The first paragraph of the Presentation Speech reads: "The Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament has awarded this year's Peace Prize to the Quakers, represented by their two great relief organizations, the Friends Service Council in London and the American Friends Service Committee in Philadelphia."[8]

See also[edit]

List of peace activists

References[edit]

- ^ Quaker Faith & Practice. Britain Yearly Meeting. 1999. pp. 1.02.31. ISBN 0-85245-306-X.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Fox 1651". quaker.org.

- ^ A declaration from the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers, London: 1660, as quoted in: Britain Yearly Meeting [Ed] Margaret Fell's Letter to the King on Persecution, 1660

- ^ from George Fox's Journal

- ^ A declaration from the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers, London: 1660, as quoted in: Britain Yearly Meeting [Ed] Quaker Faith and Practice: the book of Christian discipline of the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends in BritainLondon: 1994, 24:04. The extract quoted is considerably abridged from the original declaration - full text of the original declaration is available: A Declaration from the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers

- ^ The Nobel Peace Prize 1947 - Presentation Speech

- ^ [2][dead link]

External links[edit]

Some Early Statements Concerning the Quaker Peace Testimony

'Think Peace' - a series of six articles from Quaker Peace & Social Witness of Britain Yearly Meeting

show

v

t

e

Peace movement/Anti-war movement

hide

v

t

e

Quakers

Individuals

Susan B. Anthony

Robert Barclay

Anthony Benezet

Kenneth E. Boulding

Howard Brinton

John Cadbury

Levi Coffin

Judi Dench

Margaret Fell

George Fox

Elizabeth Fry

Edward Hicks

Elias Hicks

Herbert Hoover

Rufus Jones

Thomas R. Kelly

Benjamin Lay

Dave Matthews

Lucretia Mott

James Nayler

Richard Nixon

Parker Palmer

Alice Paul

William Penn

Robert Pleasants

Bayard Rustin

Jessamyn West

John Greenleaf Whittier

John Woolman

Groups

Yearly Meeting

Monthly Meeting

American Friends Service Committee

A Quaker Action Group

Britain Yearly Meeting

Central Yearly Meeting of Friends

Conservative Friends

Evangelical Friends Church International

Friends Committee on National Legislation

Friends General Conference

Friends United Meeting

Friends World Committee for Consultation

Nontheist Quakers

Quaker Council for European Affairs

Quaker Peace and Social Witness

Quaker United Nations Office

World Gathering of Young Friends

Testimonies

Peace

Equality

Integrity ("Truth")

Simplicity

By region

North America

Latin America

Europe

Africa

Other

Businesses, organizations and charities

Science

Clerk

Faith and Practice or Book of Discipline

History

Homosexuality

Inward light

Meeting houses

Perfectionism

Query

Schools

Tapestry

Wedding

Women

Wikimedia Commons has media related to

Wikimedia Commons has media related to