Showing posts with label Engaged Buddhism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Engaged Buddhism. Show all posts

2022/02/10

2022/01/26

Kang-nam Oh 틱낫한 스님의 기본 가르침

Facebook

틱낫한 스님의 기본 가르침

오늘 원불교 원음방송 <둥근 소리 둥근 이야기> 프로그램에서 틱낫한 스님에 대해 인터뷰하자고 해서 인터뷰 끝냈습니다. 거기서 한 이야기를 다 옮길 수는 없고 틱낫한 스님의 기본 가르침 네 가지를 간단히 소개하고자 합니다.

첫째, 평화운동입니다. 베트남 전쟁이 한창일 때 옆에서 폭탄이 터지고 사람들이 죽어가고 있는데 혼자 앉아서 참선하고 염불하고만 있는 것이 의미없다고 생각하고 평화운동에 뛰어들었습니다. 불교도 현실에 참여하여 전쟁을 끝내고 평화를 이루어 내야 한다는 의미에서 “Engaged Buddhism”(참여불교)라는 말을 만들고, 1960년대 중엽 미국으로 건너가 베트남 전쟁 종식을 위해 애쓰면서 많은 사람들에게 평화의 귀중함을 일깨워주었다. 그가 펼치는 평화운동이 베트남 정권의 비위를 거슬려 베트남으로 돌아가지 못하고 망명생활을 하다가 결국 프랑스 서남쪽에 Plum Vellage라는 수행처를 마련했지요. 플럼이란 자두 혹은 오얏이라는 뜻인데, 저는 이를 ‘오얏골’이라 번역했습니다. 일단 거기를 거점으로 하고 세계 여러 곳을 다니며 평화의 가르침을 주었습니다. 한국에 왔을 때도 남과 북이 형제임을 인식하고 평화롭게 살 것을 희망한다고 했습니다.

둘째, 그리스도교와 불교의 협력입니다. 그는 프랑스 식민지였던 베트남을 그리스도교화하려는 시도 때문에 그리스도교를 좋지 않게 보았는데, 미국으로 건너가 프린스턴 신학대학원에서 그리스도교를 공부하고, 그 유명한 토마스 머튼이나 그를 노벨 평화상 후보자로 추천한 마틴 루터 킹 목사 등을 만나면서 그리스도교를 깊이 이해하게 되어 부처님과 예수님은 인류 역사에서 피어난 두송이 아름다운 꽃이라고 하고 이 두 분의 신상을 그의 제단에 함께 모실 정도였습니다.

셋째, 영어로 “interbeing”이라고 하는 말을 만들었습니다. 화엄의 상입(相入) 상즉(相卽), 법계연기인 셈입니다. 세상 만물과 만사가 서로 연관되고 서로 의존된다는 생각입니다. 예를 들어 “I am a boy.”라고 말하면 내가 소년인 것은 나 혼자 그렇게 된 것이 아니라 내가 소년이 되기 위해서는 소녀라는 말이 있어야 하고, 나아가 나의 부모, 내가 먹은 밥, 공기, 햇빛 등 모두가 내가 소년이란 말에 다 들어가 있다는 것입니다. 영어로 I am a boy이는 결국 I interam a boy이라는 뜻이라는 것입니다. 영어로 interdependence, interrelatedness, interpenetration, mutual identification 등의 말보다 훨씬 알아듣기 쉬운 말이라 할 수 있습니다.

(여담: 얼마전 정청래 의원이 어느 연설에서 “여러분이 신고 있는 구두를 만드는데 몇 사람이 필요했겠는가”하는 질문을 했습니다. 어느 분은 세 사람, 열 사람, 백 사람 등등 대답했습니다. 정청래 의원은 구두 만든 사람은 물론 가죽을 만드는 사람, 가죽을 실어다 주는 사람, 트럭 운전사, 트럭 만드는 사람, 길을 만드는 사람, 구두 밑 고무는 고무 나무에서 고무를 체집하는 사람, 배로 실어오는 사람, 배 만든 사람 등등 무한한 사람들이 필요하다는 이야기를 했습니다. 사실 사람들만 필요한 것이 아니라 소도 필요하고 소가 먹는 풀도 필요하고 풀이 자라도록 하는 비나 흙이나 공기나 햇빛 등등 다 필요한 것입니다. 정 의원이 의식했는지 모르지만 사실 이것은 화엄사상의 골자인 셈입니다. 구두 하나에 온 우주가 들어있는데, 불교에서는 이를 一微塵中含十方이라 하지요. 이렇게 화엄불교를 쉽게 풀이하여 준 정 의원을 지금 불교 일부에서 비난을 한다니 아이러니네요.)

넷째, 그의 가르침 중 가장 중요한 것은 “마음 챙김”입니다. 영어로 mindfulness라고 합니다. 사제팔정도 중 정념(正念)을 그렇게 번역했습니다. 우리가 지금 여기서 하는 행동 하나하나에 온 정신을 집중하라는 뜻입니다. 그렇게 되면 매 순간이 평화요 극락이요 천국이 되는 것이라 봅니다.

틱낫한 스님의 가장 큰 공헌은 불교를 대중화했다는 것입니다. 불교의 기본 가르침을 종교의 경계를 넘어 어느 종교에 속했든 누구나 이해하고 실천하기 쉽도록 제시했다는 것입니다. 그를 따르던 사람들은 불자 뿐 아니라 이웃 종교인들, 일반인들이 많았습니다.

이제 95세로 입멸하셨지만 영어로 된 100여권의 책으로 그의 가르침은 계속되고 그 영향력은 오래 갈 것이라 믿습니다.

청취권 : 서울 경기지역 FM 89.7 | 부산 영남지역 FM 104.9

대구 경북지역 FM 98.3 | 광주 전남지역 FM 107.9

전북 충남지역 FM 97.9 MHz

2022/01/23

Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Zen Master, Dies at 95 - Tricycle

Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Zen Master, Dies at 95 - Tricycle

Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Zen Master, Dies at 95

The beloved teacher and civil rights activist was a pioneer of engaged Buddhism who popularized mindfulness around the world.By Joan Duncan OliverJAN 21, 2022

Thich Nhat Hanh at the Plum Village monastery in southern France | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Thich Nhat Hanh at the Plum Village monastery in southern France | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Vietnamese Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh—a world-renowned spiritual leader, author, poet, and peace activist—died on January 22, 2022 at midnight (ICT) at his root temple, Tu Hien Temple, in Hue, Vietnam. He was 95.

“Our beloved teacher Thich Nhat Hanh has passed away peacefully,” his sangha, the Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, said in a statement. “We invite our global spiritual family to take a few moments to be still, to come back to our mindful breathing, as we together hold Thay in our hearts in peace and loving gratitude for all he has offered the world.”

Thich Nhat Hanh had been in declining health since suffering a severe brain hemorrhage in November 2014, and shortly after his 93rd birthday on October 10, 2019, he had left Tu Hien Temple to visit a hospital in Bangkok and stayed for a few weeks at Thai Plum Village in Pak Chong, near Khao Yai National Park before returning to Hue on January 4, 2020. He had returned to Vietnam in late 2018, expressing a wish to spend his remaining days at his root temple.

Known to his thousands of followers worldwide as Thây—Vietnamese for teacher—Nhat Hanh was widely considered among Buddhists as second only to His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama in the scope of his global influence. The author of some 100 books—75 in English—he founded nine monasteries and dozens of affiliated practice centers, and inspired the creation of thousands of local mindfulness communities. Nhat Hanh is credited with popularizing mindfulness and “engaged Buddhism” (he coined the term), teachings that not only are central to contemporary Buddhist practice but also have penetrated the mainstream. For many years, Thich Nhat Hanh has been a familiar sight the world over, leading long lines of people in silent “mindful” walking meditation.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Thich Nhat Hanh’s role in the development of Buddhism in the West, particularly in the United States. He was arguably the most significant catalyst for the Buddhist community’s engagement with social, political, and environmental concerns. Today, this aspect of Western Buddhism is widely accepted, but when Nhat Hanh began teaching regularly in North America, activism was highly controversial in Buddhist circles, frowned upon by most Buddhist leaders, who considered it a distraction from the focus on awakening. At a time when Western Buddhism was notably parochial, Nhat Hanh’s nonsectarian view motivated many teachers to reach out and build bonds with other dharma communities and traditions. It would not be an exaggeration to say that his inclusive vision laid the groundwork for the flourishing of Buddhist publications, including Tricycle, over the past 35 years.

At the heart of Thich Nhat Hanh’s approach to Buddhism was his emphasis on dependent origination, or what he called “interbeing.” Although this is a core teaching shared by all schools of Buddhism, prior to Nhat Hanh, it received little attention among Western Buddhists outside of academia. Today, it is central to dharma practice. Nhat Hanh viewed dependent origination as the thread that tied together all Buddhist traditions, linking the teachings of the Pali canon, the Mahayana teachings on emptiness, and the Huayen school’s vision of radical interdependence.

While Thich Nhat Hanh was a singular and innovative teacher and leader, he was also steeped in the Buddhist tradition of his native Vietnam. More than any other Zen master, he brought the essential character of Vietnamese Buddhism—ecumenical, cosmopolitan, politically engaged, artistically oriented—to the mix of cultural influences that have nourished the development of Buddhism in the West. Thich Nhat Hanh | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Thich Nhat Hanh | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Born Nguyen Xuan Bao in central Vietnam in 1926, Nhat Hanh was 16 when he joined Tu Hieu Temple in Hue as a novice monk in the Linchi (Rinzai in Japanese) school of Vietnamese Zen. He studied at the Bao Quoc Buddhist Academy but became dissatisfied with the conservatism of the teachings and sought to make Buddhist practice more relevant to everyday life. (Tellingly, he was the first monk in Vietnam to ride a bicycle.) Seeking exposure to modern ideas, he studied science at Saigon University, later returning to the Buddhist Academy, which incorporated some of the reforms he had proposed. Nhat Hanh took full ordination in 1949 at Tu Hieu, where his primary teacher was Zen master Thanh Quý Chân Thậ.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Nhat Hanh assumed leadership roles that were harbingers of the prolific writing and unrelenting activism that his future held in store. In the early 50s, he started a magazine, The First Lotus Flowers of the Season, for visionaries promoting reforms, and later edited Vietnamese Buddhism, a periodical of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV), a group that united various Buddhist sects in response to government persecution at the time. In 1961, Vietnamese Buddhism was closed down by conservative Buddhist leaders, but Nhat Hanh continued to write in opposition to government repression and to the war that was escalating in Vietnam.

Nhat Hanh first traveled to the United States in 1961, to study comparative religion at Princeton University. The following year, he was invited to teach Buddhism at Columbia University. In 1963, as the Diem regime increased pressure on Vietnamese Buddhists, Nhat Hanh traveled around the US to garner support for peace efforts at home. After the fall of Diem, he returned to Vietnam, and in 1964 devoted himself to peace activism alongside fellow monks. Nhat Hanh became a widely visible opponent of the war, and established the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS), a training program for Buddhist peace workers who brought schooling, health care, and basic infrastructure to villages throughout Vietnam. In February 1966, with six SYSS leaders, he established the Order of Interbeing, an international sangha devoted to inner peace and social justice, guided by his deep ethical commitment to interdependence among all beings.

On May 1, 1966, at Tu Hieu Temple, Nhat Hanh received dharma transmission from Master Chan That, becoming a teacher of the Lieu Quan dharma line in the forty-second generation of the Lam Te Dhyana school. Shortly thereafter, he toured North America, calling for an end to hostilities in his country. He urged US Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara to stop bombing Vietnam and, at a press conference, outlined a five-point peace proposal. On that trip he also met with the Trappist monk, social activist, and author Thomas Merton at Merton’s abbey in Kentucky. Recognizing a kindred spirit, Merton later published an essay, “Nhat Hanh Is My Brother.” Thich Nhat Hanh with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at a joint press conference on May, 31 1966 Chicago Sheraton Hotel | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Thich Nhat Hanh with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at a joint press conference on May, 31 1966 Chicago Sheraton Hotel | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

While in the US, Nhat Hanh urged the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to publicly condemn the war in Vietnam. In April 1967, King spoke out against the war in a famous speech at New York City’s Riverside Church. A Nobel Laureate, King nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize in a letter to the Nobel Committee that called the Vietnamese monk “an apostle of peace and nonviolence, cruelly separated from his own people while they are oppressed by a vicious war.” Nhat Hanh did not receive the Nobel Peace Prize: in publicly announcing the nomination, King had violated a strict prohibition of the Nobel Committee.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s anti-war activism and refusal to take sides angered both North and South Vietnam, and following his tour of the US and Europe, he was barred from returning to his native land. He was granted asylum in France, where he was named to lead the Buddhist peace delegation to the Paris Peace Accords. In 1975, Nhat Hanh founded Les Patates Douce, or the “Sweet Potato” community near Paris. In 1982, it moved to the Dordogne in southwestern France and was renamed Plum Village. What began as a small rural sangha has since grown into a home for over 200 monastics and some 8,000 yearly visitors. Always a strong supporter of children, Nhat Hanh also founded Wake Up, an international network of sanghas for young people.

After 39 years in exile, Nhat Hanh returned to Vietnam for the first time in 2005 and again in 2007. During these visits, he gave teachings to crowds numbering in the thousands and also met with the sitting Vietnamese president, Nguyen Minh Triet. Though greeted with considerable fanfare, the trips also prompted criticism from Nhat Hanh’s former peers at UBCV, who thought the visits granted credibility to an oppressive regime. But consistent with his stand of many years, Nhat Hanh made both private and public proposals urging the Vietnamese government to ease its restrictions on religious practice.

Fluent in English, French, and Chinese, as well as Vietnamese, Nhat Hanh continued to travel the world teaching and leading retreats until his stroke in 2014, which left him unable to speak. But Nhat Hanh’s legacy carries on in his vast catalogue of written work, which includes accessible teachings, rigorous scholarship, scriptural commentary, political thought, and poetry. Beloved for his warm, evocative verse, Nhat Hanh published a collection of poetry entitled Call Me By My True Names in 1996. His instructive and explicatory work includes Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire, published in 1967, and such best-sellers as Peace is Every Step (1992), The Miracle of Mindfulness (1975, reissued 1999), and Living Buddha, Living Christ (1995).

In addition to his followers worldwide, Nhat Hanh leaves behind many close brothers and sisters in the dharma, most notably Sister Chan Khong. A longtime friend and activist in her own right, she has assumed a more pronounced leadership role in the sangha in recent years.

♦

ARTICLES BY THICH NHAT HANH

Interbeing with Thich Nhat Hanh: An Interview

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh was born in central Vietnam in October 1926 and became a monk at the age of sixteen.

The Fertile Soil of Sangha

Thich Nhat Hanh on the importance of community.

The Heart of the Matter

Thich Nhat Hanh answers three questions about our emotions

Walk Like a Buddha

Arrive in the here and the now.

Free from Fear

When we are not fully present, we are not really living

Cultivating Compassion

How to love yourself and others

Thich Nhat Hanh’s Little Peugeot

The Zen master reflects on our culture of empty consumption and his community’s connection to an old French car.

Why We Shouldn’t Be Afraid of Suffering

Instead, we should fear not knowing how to handle our suffering, according to Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh.

Fear of Silence

While we can connect to others more readily than ever before, are we losing our connection to body and mind? A Zen master thinks so, and offers a nourishing conscious breathing practice as a remedy.

Get Daily Dharma in your email

Start your day with a fresh perspective

Joan Duncan Oliver is a Tricycle contributing editor. The author of five books, she edited Commit to Sit, an anthology of articles from Tricycle.

Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Zen Master, Dies at 95

The beloved teacher and civil rights activist was a pioneer of engaged Buddhism who popularized mindfulness around the world.By Joan Duncan OliverJAN 21, 2022

Thich Nhat Hanh at the Plum Village monastery in southern France | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Thich Nhat Hanh at the Plum Village monastery in southern France | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged BuddhismVietnamese Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh—a world-renowned spiritual leader, author, poet, and peace activist—died on January 22, 2022 at midnight (ICT) at his root temple, Tu Hien Temple, in Hue, Vietnam. He was 95.

“Our beloved teacher Thich Nhat Hanh has passed away peacefully,” his sangha, the Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, said in a statement. “We invite our global spiritual family to take a few moments to be still, to come back to our mindful breathing, as we together hold Thay in our hearts in peace and loving gratitude for all he has offered the world.”

Thich Nhat Hanh had been in declining health since suffering a severe brain hemorrhage in November 2014, and shortly after his 93rd birthday on October 10, 2019, he had left Tu Hien Temple to visit a hospital in Bangkok and stayed for a few weeks at Thai Plum Village in Pak Chong, near Khao Yai National Park before returning to Hue on January 4, 2020. He had returned to Vietnam in late 2018, expressing a wish to spend his remaining days at his root temple.

Known to his thousands of followers worldwide as Thây—Vietnamese for teacher—Nhat Hanh was widely considered among Buddhists as second only to His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama in the scope of his global influence. The author of some 100 books—75 in English—he founded nine monasteries and dozens of affiliated practice centers, and inspired the creation of thousands of local mindfulness communities. Nhat Hanh is credited with popularizing mindfulness and “engaged Buddhism” (he coined the term), teachings that not only are central to contemporary Buddhist practice but also have penetrated the mainstream. For many years, Thich Nhat Hanh has been a familiar sight the world over, leading long lines of people in silent “mindful” walking meditation.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Thich Nhat Hanh’s role in the development of Buddhism in the West, particularly in the United States. He was arguably the most significant catalyst for the Buddhist community’s engagement with social, political, and environmental concerns. Today, this aspect of Western Buddhism is widely accepted, but when Nhat Hanh began teaching regularly in North America, activism was highly controversial in Buddhist circles, frowned upon by most Buddhist leaders, who considered it a distraction from the focus on awakening. At a time when Western Buddhism was notably parochial, Nhat Hanh’s nonsectarian view motivated many teachers to reach out and build bonds with other dharma communities and traditions. It would not be an exaggeration to say that his inclusive vision laid the groundwork for the flourishing of Buddhist publications, including Tricycle, over the past 35 years.

At the heart of Thich Nhat Hanh’s approach to Buddhism was his emphasis on dependent origination, or what he called “interbeing.” Although this is a core teaching shared by all schools of Buddhism, prior to Nhat Hanh, it received little attention among Western Buddhists outside of academia. Today, it is central to dharma practice. Nhat Hanh viewed dependent origination as the thread that tied together all Buddhist traditions, linking the teachings of the Pali canon, the Mahayana teachings on emptiness, and the Huayen school’s vision of radical interdependence.

While Thich Nhat Hanh was a singular and innovative teacher and leader, he was also steeped in the Buddhist tradition of his native Vietnam. More than any other Zen master, he brought the essential character of Vietnamese Buddhism—ecumenical, cosmopolitan, politically engaged, artistically oriented—to the mix of cultural influences that have nourished the development of Buddhism in the West.

Thich Nhat Hanh | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Thich Nhat Hanh | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged BuddhismBorn Nguyen Xuan Bao in central Vietnam in 1926, Nhat Hanh was 16 when he joined Tu Hieu Temple in Hue as a novice monk in the Linchi (Rinzai in Japanese) school of Vietnamese Zen. He studied at the Bao Quoc Buddhist Academy but became dissatisfied with the conservatism of the teachings and sought to make Buddhist practice more relevant to everyday life. (Tellingly, he was the first monk in Vietnam to ride a bicycle.) Seeking exposure to modern ideas, he studied science at Saigon University, later returning to the Buddhist Academy, which incorporated some of the reforms he had proposed. Nhat Hanh took full ordination in 1949 at Tu Hieu, where his primary teacher was Zen master Thanh Quý Chân Thậ.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Nhat Hanh assumed leadership roles that were harbingers of the prolific writing and unrelenting activism that his future held in store. In the early 50s, he started a magazine, The First Lotus Flowers of the Season, for visionaries promoting reforms, and later edited Vietnamese Buddhism, a periodical of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV), a group that united various Buddhist sects in response to government persecution at the time. In 1961, Vietnamese Buddhism was closed down by conservative Buddhist leaders, but Nhat Hanh continued to write in opposition to government repression and to the war that was escalating in Vietnam.

Nhat Hanh first traveled to the United States in 1961, to study comparative religion at Princeton University. The following year, he was invited to teach Buddhism at Columbia University. In 1963, as the Diem regime increased pressure on Vietnamese Buddhists, Nhat Hanh traveled around the US to garner support for peace efforts at home. After the fall of Diem, he returned to Vietnam, and in 1964 devoted himself to peace activism alongside fellow monks. Nhat Hanh became a widely visible opponent of the war, and established the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS), a training program for Buddhist peace workers who brought schooling, health care, and basic infrastructure to villages throughout Vietnam. In February 1966, with six SYSS leaders, he established the Order of Interbeing, an international sangha devoted to inner peace and social justice, guided by his deep ethical commitment to interdependence among all beings.

On May 1, 1966, at Tu Hieu Temple, Nhat Hanh received dharma transmission from Master Chan That, becoming a teacher of the Lieu Quan dharma line in the forty-second generation of the Lam Te Dhyana school. Shortly thereafter, he toured North America, calling for an end to hostilities in his country. He urged US Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara to stop bombing Vietnam and, at a press conference, outlined a five-point peace proposal. On that trip he also met with the Trappist monk, social activist, and author Thomas Merton at Merton’s abbey in Kentucky. Recognizing a kindred spirit, Merton later published an essay, “Nhat Hanh Is My Brother.”

Thich Nhat Hanh with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at a joint press conference on May, 31 1966 Chicago Sheraton Hotel | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism

Thich Nhat Hanh with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at a joint press conference on May, 31 1966 Chicago Sheraton Hotel | Courtesy Plum Village Community of Engaged BuddhismWhile in the US, Nhat Hanh urged the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to publicly condemn the war in Vietnam. In April 1967, King spoke out against the war in a famous speech at New York City’s Riverside Church. A Nobel Laureate, King nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize in a letter to the Nobel Committee that called the Vietnamese monk “an apostle of peace and nonviolence, cruelly separated from his own people while they are oppressed by a vicious war.” Nhat Hanh did not receive the Nobel Peace Prize: in publicly announcing the nomination, King had violated a strict prohibition of the Nobel Committee.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s anti-war activism and refusal to take sides angered both North and South Vietnam, and following his tour of the US and Europe, he was barred from returning to his native land. He was granted asylum in France, where he was named to lead the Buddhist peace delegation to the Paris Peace Accords. In 1975, Nhat Hanh founded Les Patates Douce, or the “Sweet Potato” community near Paris. In 1982, it moved to the Dordogne in southwestern France and was renamed Plum Village. What began as a small rural sangha has since grown into a home for over 200 monastics and some 8,000 yearly visitors. Always a strong supporter of children, Nhat Hanh also founded Wake Up, an international network of sanghas for young people.

After 39 years in exile, Nhat Hanh returned to Vietnam for the first time in 2005 and again in 2007. During these visits, he gave teachings to crowds numbering in the thousands and also met with the sitting Vietnamese president, Nguyen Minh Triet. Though greeted with considerable fanfare, the trips also prompted criticism from Nhat Hanh’s former peers at UBCV, who thought the visits granted credibility to an oppressive regime. But consistent with his stand of many years, Nhat Hanh made both private and public proposals urging the Vietnamese government to ease its restrictions on religious practice.

Fluent in English, French, and Chinese, as well as Vietnamese, Nhat Hanh continued to travel the world teaching and leading retreats until his stroke in 2014, which left him unable to speak. But Nhat Hanh’s legacy carries on in his vast catalogue of written work, which includes accessible teachings, rigorous scholarship, scriptural commentary, political thought, and poetry. Beloved for his warm, evocative verse, Nhat Hanh published a collection of poetry entitled Call Me By My True Names in 1996. His instructive and explicatory work includes Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire, published in 1967, and such best-sellers as Peace is Every Step (1992), The Miracle of Mindfulness (1975, reissued 1999), and Living Buddha, Living Christ (1995).

In addition to his followers worldwide, Nhat Hanh leaves behind many close brothers and sisters in the dharma, most notably Sister Chan Khong. A longtime friend and activist in her own right, she has assumed a more pronounced leadership role in the sangha in recent years.

♦

ARTICLES BY THICH NHAT HANH

Interbeing with Thich Nhat Hanh: An Interview

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh was born in central Vietnam in October 1926 and became a monk at the age of sixteen.

The Fertile Soil of Sangha

Thich Nhat Hanh on the importance of community.

The Heart of the Matter

Thich Nhat Hanh answers three questions about our emotions

Walk Like a Buddha

Arrive in the here and the now.

Free from Fear

When we are not fully present, we are not really living

Cultivating Compassion

How to love yourself and others

Thich Nhat Hanh’s Little Peugeot

The Zen master reflects on our culture of empty consumption and his community’s connection to an old French car.

Why We Shouldn’t Be Afraid of Suffering

Instead, we should fear not knowing how to handle our suffering, according to Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh.

Fear of Silence

While we can connect to others more readily than ever before, are we losing our connection to body and mind? A Zen master thinks so, and offers a nourishing conscious breathing practice as a remedy.

Get Daily Dharma in your email

Start your day with a fresh perspective

Joan Duncan Oliver is a Tricycle contributing editor. The author of five books, she edited Commit to Sit, an anthology of articles from Tricycle.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s final mindfulness lesson: how to die peacefully | Plum Village

Thich Nhat Hanh’s final mindfulness lesson: how to die peacefully | Plum Village

March 11, 2019

Thich Nhat Hanh’s final mindfulness lesson: how to die peacefully

A new interview with Brother Phap Dung on Vox about how Thay is living his days.

By Eliza Barclay | 11th March, 2019

“Letting go is also the practice of letting in, letting your teacher be alive in you,” says a senior disciple of the celebrity Buddhist monk and author.

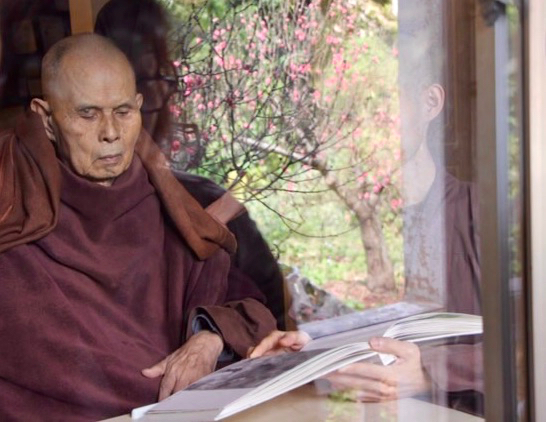

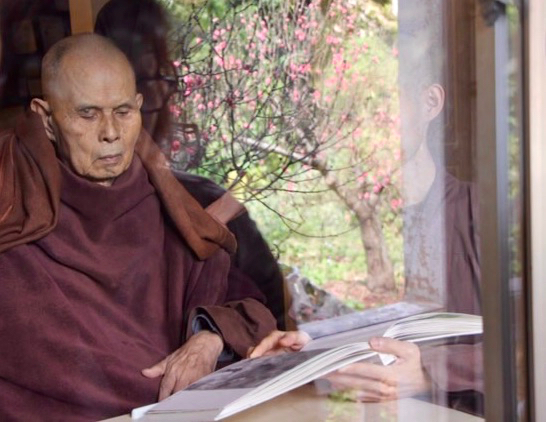

Thich Naht Hanh, 92, reads a book in January 2019 at the Tu Hieu temple. “For him to return to Vietnam is to point out that we are a stream,” says his senior disciple Brother Phap Dung.

Thich Naht Hanh, 92, reads a book in January 2019 at the Tu Hieu temple. “For him to return to Vietnam is to point out that we are a stream,” says his senior disciple Brother Phap Dung.

Thich Nhat Hanh has done more than perhaps any Buddhist alive today to articulate and disseminate the core Buddhist teachings of mindfulness, kindness, and compassion to a broad global audience. The Vietnamese monk, who has written more than 100 books, is second only to the Dalai Lama in fame and influence.

Nhat Hanh made his name doing human rights and reconciliation work during the Vietnam War, which led Martin Luther King Jr. to nominate him for a Nobel Prize.

He’s considered the father of “engaged Buddhism,” a movement linking mindfulness practice with social action. He’s also built a network of monasteries and retreat centers in six countries around the world, including the United States.

In 2014, Nhat Hanh, who is now 92 years old, had a stroke at Plum Village, the monastery and retreat center in southwest France he founded in 1982 that was also his home base. Though he was unable to speak after the stroke, he continued to lead the community, using his left arm and facial expressions to communicate.

In October 2018, Nhat Hanh stunned his disciples by informing them that he would like to return home to Vietnam to pass his final days at the Tu Hieu root temple in Hue, where he became a monk in 1942 at age 16.

As Time’s Liam Fitzpatrick wrote, Nhat Hanh was exiled from Vietnam for his antiwar activism from 1966 until he was finally invited back in 2005. But his return to his homeland is less about political reconciliation than something much deeper. And it contains lessons for all of us about how to die peacefully and how to let go of the people we love.

When I heard that Nhat Hanh had returned to Vietnam, I wanted to learn more about the decision. So I called up Brother Phap Dung, a senior disciple and monk who is helping to run Plum Village in Nhat Hanh’s absence. (I spoke to Br. Phap Dung in 2016 right after Donald Trump won the presidential election, about how we can use mindfulness in times of conflict.)

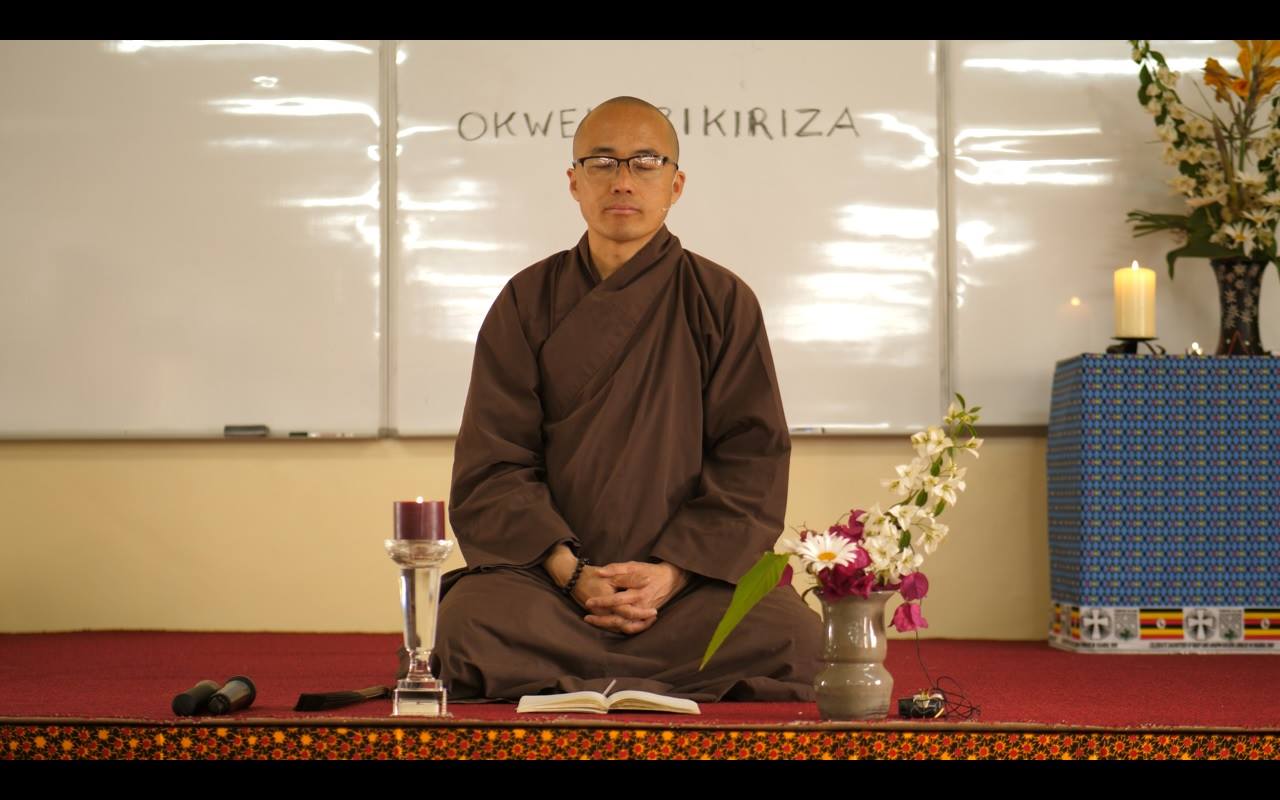

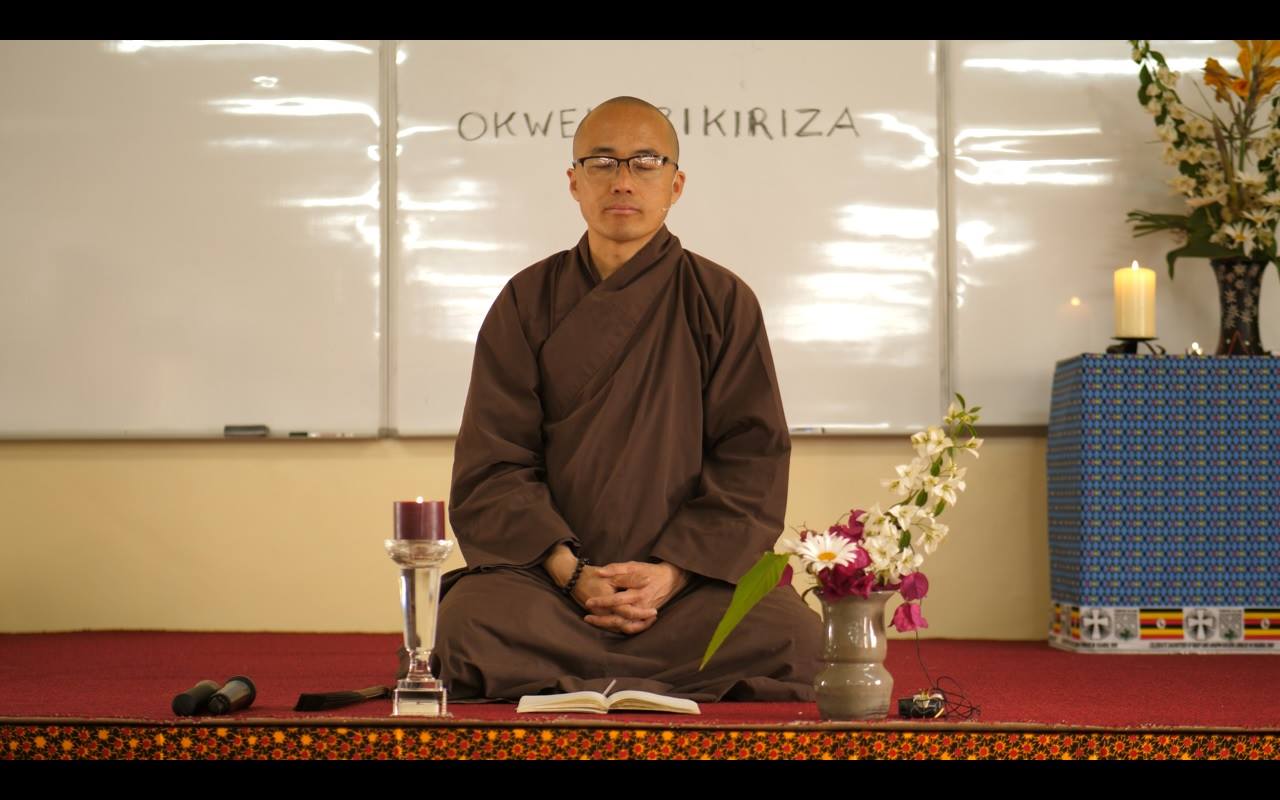

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity. Brother Phap Dung, a senior disciple of Thich Nhat Hanh, leading a meditation on a trip to Uganda in early 2019.

Brother Phap Dung, a senior disciple of Thich Nhat Hanh, leading a meditation on a trip to Uganda in early 2019.

Eliza Barclay

Tell me about your teacher’s decision to go to Vietnam and how you interpret the meaning of it.

Phap Dung

He’s definitely coming back to his roots.

He has come back to the place where he grew up as a monk. The message is to remember we don’t come from nowhere. We have roots. We have ancestors. We are part of a lineage or stream.

It’s a beautiful message, to see ourselves as a stream, as a lineage, and it is the deepest teaching in Buddhism: non-self. We are empty of a separate self, and yet at the same time, we are full of our ancestors.

He has emphasized this Vietnamese tradition of ancestral worship as a practice in our community. Worship here means to remember. For him to return to Vietnam is to point out that we are a stream that runs way back to the time of the Buddha in India, beyond even Vietnam and China.

Eliza Barclay

So he is reconnecting to the stream that came before him. And that suggests the larger community he has built is connected to that stream too. The stream will continue flowing after him.

Phap Dung

It’s like the circle that he often draws with the calligraphy brush. He’s returned to Vietnam after 50 years of being in the West. When he first left to call for peace during the Vietnam War was the start of the circle; slowly, he traveled to other countries to do the teaching, making the rounds. And then slowly he returned to Asia, to Indonesia, Hong Kong, China. Eventually, Vietnam opened up to allow him to return three other times. This return now is kind of like a closing of the circle.

It’s also like the light of the candle being transferred, to the next candle, to many other candles, for us to continue to live and practice and to continue his work. For me, it feels like that, like the light is lit in each one of us.

Eliza Barclay

And as one of his senior monks, do you feel like you are passing the candle too?

Phap Dung

Before I met Thay in 1992, I was not aware, I was running busy and doing my architectural, ambitious things in the US. But he taught me to really enjoy living in the present moment, that it is something that we can train in.

Now as I practice, I am keeping the candlelight illuminated, and I can also share the practice with others. Now I’m teaching and caring for the monks, nuns, and lay friends who come to our community just as our teacher did.

Eliza Barclay

So he is 92 and his health is fragile, but he is not bedridden. What is he up to in Vietnam?

Phap Dung

The first thing he did when he got there was to go to the stupa [shrine], light a candle, and touch the earth. Paying respect like that — it’s like plugging in. You can get so much energy when you can remember your teacher.

He’s not sitting around waiting. He is doing his best to enjoy the rest of his life. He is eating regularly. He even can now drink tea and invite his students to enjoy a cup with him. And his actions are very deliberate.

Once, the attendants took him out to visit before the lunar new year to enjoy the flower market. On their way back, he directed the entourage to change course and to go to a few particular temples. At first, everyone was confused, until they found out that these temples had an affiliation to our community. He remembered the exact location of these temples and the direction to get there. The attendants realized that he wanted to visit the temple of a monk who had lived a long time in Plum Village, France; and another one where he studied as a young monk. It’s very clear that although he’s physically limited, and in a wheelchair, he is still living his life, doing what his body and health allows.

Anytime he’s healthy enough, he shows up for sangha gatherings and community gatherings. Even though he doesn’t have to do anything. For him, there is no such thing as retirement.

Eliza Barclay

But you are also in this process of letting him go, right?

Phap Dung

Of course, letting go is one of our main practices. It goes along with recognizing the impermanent nature of things, of the world, and of our loved ones.

This transition period is his last and deepest teaching to our community. He is showing us how to make the transition gracefully, even after the stroke and being limited physically. He still enjoys his day every chance he gets.

My practice is not to wait for the moment when he takes his last breath. Each day I practice to let him go, by letting him be with me, within me, and with each of my conscious breaths. He is alive in my breath, in my awareness.

Breathing in, I breathe with my teacher within me; breathing out, I see him smiling with me. When we make a step with gentleness, we let him walk with us, and we allow him to continue within our steps. Letting go is also the practice of letting in, letting your teacher be alive in you, and to see that he is more than just a physical body now in Vietnam.

Eliza Barclay

What have you learned about dying from your teacher?

Phap Dung

There is dying in the sense of letting this body go, letting go of feelings, emotions, these things we call our identity, and practicing to let those go.

The trouble is, we don’t let ourselves die day by day. Instead, we carry ideas about each other and ourselves. Sometimes it’s good, but sometimes it’s detrimental to our growth. We brand ourselves and imprison ourselves to an idea.

Letting go is a practice not only when you reach 90. It’s one of the highest practices. This can move you toward equanimity, a state of freedom, a form of peace. Waking up each day as a rebirth, now that is a practice.

In the historical dimension, we practice to accept that we will get to a point where the body will be limited and we will be sick. There is birth, old age, sickness, and death. How will we deal with it?

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15947235/Plum_Village_Practice_Center___Thich_Nhat_Hanh_leading_walking_meditation_in_Plum_Village__France__2014_.jpg)

March 11, 2019

Thich Nhat Hanh’s final mindfulness lesson: how to die peacefully

A new interview with Brother Phap Dung on Vox about how Thay is living his days.

By Eliza Barclay | 11th March, 2019

“Letting go is also the practice of letting in, letting your teacher be alive in you,” says a senior disciple of the celebrity Buddhist monk and author.

Thich Naht Hanh, 92, reads a book in January 2019 at the Tu Hieu temple. “For him to return to Vietnam is to point out that we are a stream,” says his senior disciple Brother Phap Dung.

Thich Naht Hanh, 92, reads a book in January 2019 at the Tu Hieu temple. “For him to return to Vietnam is to point out that we are a stream,” says his senior disciple Brother Phap Dung.Thich Nhat Hanh has done more than perhaps any Buddhist alive today to articulate and disseminate the core Buddhist teachings of mindfulness, kindness, and compassion to a broad global audience. The Vietnamese monk, who has written more than 100 books, is second only to the Dalai Lama in fame and influence.

Nhat Hanh made his name doing human rights and reconciliation work during the Vietnam War, which led Martin Luther King Jr. to nominate him for a Nobel Prize.

He’s considered the father of “engaged Buddhism,” a movement linking mindfulness practice with social action. He’s also built a network of monasteries and retreat centers in six countries around the world, including the United States.

In 2014, Nhat Hanh, who is now 92 years old, had a stroke at Plum Village, the monastery and retreat center in southwest France he founded in 1982 that was also his home base. Though he was unable to speak after the stroke, he continued to lead the community, using his left arm and facial expressions to communicate.

In October 2018, Nhat Hanh stunned his disciples by informing them that he would like to return home to Vietnam to pass his final days at the Tu Hieu root temple in Hue, where he became a monk in 1942 at age 16.

As Time’s Liam Fitzpatrick wrote, Nhat Hanh was exiled from Vietnam for his antiwar activism from 1966 until he was finally invited back in 2005. But his return to his homeland is less about political reconciliation than something much deeper. And it contains lessons for all of us about how to die peacefully and how to let go of the people we love.

When I heard that Nhat Hanh had returned to Vietnam, I wanted to learn more about the decision. So I called up Brother Phap Dung, a senior disciple and monk who is helping to run Plum Village in Nhat Hanh’s absence. (I spoke to Br. Phap Dung in 2016 right after Donald Trump won the presidential election, about how we can use mindfulness in times of conflict.)

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Brother Phap Dung, a senior disciple of Thich Nhat Hanh, leading a meditation on a trip to Uganda in early 2019.

Brother Phap Dung, a senior disciple of Thich Nhat Hanh, leading a meditation on a trip to Uganda in early 2019.Eliza Barclay

Tell me about your teacher’s decision to go to Vietnam and how you interpret the meaning of it.

Phap Dung

He’s definitely coming back to his roots.

He has come back to the place where he grew up as a monk. The message is to remember we don’t come from nowhere. We have roots. We have ancestors. We are part of a lineage or stream.

It’s a beautiful message, to see ourselves as a stream, as a lineage, and it is the deepest teaching in Buddhism: non-self. We are empty of a separate self, and yet at the same time, we are full of our ancestors.

He has emphasized this Vietnamese tradition of ancestral worship as a practice in our community. Worship here means to remember. For him to return to Vietnam is to point out that we are a stream that runs way back to the time of the Buddha in India, beyond even Vietnam and China.

Eliza Barclay

So he is reconnecting to the stream that came before him. And that suggests the larger community he has built is connected to that stream too. The stream will continue flowing after him.

Phap Dung

It’s like the circle that he often draws with the calligraphy brush. He’s returned to Vietnam after 50 years of being in the West. When he first left to call for peace during the Vietnam War was the start of the circle; slowly, he traveled to other countries to do the teaching, making the rounds. And then slowly he returned to Asia, to Indonesia, Hong Kong, China. Eventually, Vietnam opened up to allow him to return three other times. This return now is kind of like a closing of the circle.

It’s also like the light of the candle being transferred, to the next candle, to many other candles, for us to continue to live and practice and to continue his work. For me, it feels like that, like the light is lit in each one of us.

Eliza Barclay

And as one of his senior monks, do you feel like you are passing the candle too?

Phap Dung

Before I met Thay in 1992, I was not aware, I was running busy and doing my architectural, ambitious things in the US. But he taught me to really enjoy living in the present moment, that it is something that we can train in.

Now as I practice, I am keeping the candlelight illuminated, and I can also share the practice with others. Now I’m teaching and caring for the monks, nuns, and lay friends who come to our community just as our teacher did.

Eliza Barclay

So he is 92 and his health is fragile, but he is not bedridden. What is he up to in Vietnam?

Phap Dung

The first thing he did when he got there was to go to the stupa [shrine], light a candle, and touch the earth. Paying respect like that — it’s like plugging in. You can get so much energy when you can remember your teacher.

He’s not sitting around waiting. He is doing his best to enjoy the rest of his life. He is eating regularly. He even can now drink tea and invite his students to enjoy a cup with him. And his actions are very deliberate.

Once, the attendants took him out to visit before the lunar new year to enjoy the flower market. On their way back, he directed the entourage to change course and to go to a few particular temples. At first, everyone was confused, until they found out that these temples had an affiliation to our community. He remembered the exact location of these temples and the direction to get there. The attendants realized that he wanted to visit the temple of a monk who had lived a long time in Plum Village, France; and another one where he studied as a young monk. It’s very clear that although he’s physically limited, and in a wheelchair, he is still living his life, doing what his body and health allows.

Anytime he’s healthy enough, he shows up for sangha gatherings and community gatherings. Even though he doesn’t have to do anything. For him, there is no such thing as retirement.

Eliza Barclay

But you are also in this process of letting him go, right?

Phap Dung

Of course, letting go is one of our main practices. It goes along with recognizing the impermanent nature of things, of the world, and of our loved ones.

This transition period is his last and deepest teaching to our community. He is showing us how to make the transition gracefully, even after the stroke and being limited physically. He still enjoys his day every chance he gets.

My practice is not to wait for the moment when he takes his last breath. Each day I practice to let him go, by letting him be with me, within me, and with each of my conscious breaths. He is alive in my breath, in my awareness.

Breathing in, I breathe with my teacher within me; breathing out, I see him smiling with me. When we make a step with gentleness, we let him walk with us, and we allow him to continue within our steps. Letting go is also the practice of letting in, letting your teacher be alive in you, and to see that he is more than just a physical body now in Vietnam.

Eliza Barclay

What have you learned about dying from your teacher?

Phap Dung

There is dying in the sense of letting this body go, letting go of feelings, emotions, these things we call our identity, and practicing to let those go.

The trouble is, we don’t let ourselves die day by day. Instead, we carry ideas about each other and ourselves. Sometimes it’s good, but sometimes it’s detrimental to our growth. We brand ourselves and imprison ourselves to an idea.

Letting go is a practice not only when you reach 90. It’s one of the highest practices. This can move you toward equanimity, a state of freedom, a form of peace. Waking up each day as a rebirth, now that is a practice.

In the historical dimension, we practice to accept that we will get to a point where the body will be limited and we will be sick. There is birth, old age, sickness, and death. How will we deal with it?

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15947235/Plum_Village_Practice_Center___Thich_Nhat_Hanh_leading_walking_meditation_in_Plum_Village__France__2014_.jpg)

Thich Nhat Hanh leading a walking meditation at the Plum Village practice center in France in 2014.

Eliza Barclay

What are some of the most important teachings from Buddhism about dying?

Phap Dung

We are aware that one day we are all going to deteriorate and die — our neurons, our arms, our flesh and bones. But if our practice and our awareness is strong enough, we can see beyond the dying body and pay attention also to the spiritual body. We continue through the spirit of our speech, our thinking, and our actions. These three aspects of body, speech, and mind continues.

In Buddhism, we call this the nature of no birth and no death. It is the other dimension of the ultimate. It’s not something idealized, or clean. The body has to do what it does, and the mind as well.

But in the ultimate dimension, there is continuation. We can cultivate this awareness of this nature of no birth and no death, this way of living in the ultimate dimension; then slowly our fear of death will lessen.

This awareness also helps us be more mindful in our daily life, to cherish every moment and everyone in our life.

One of the most powerful teachings that he shared with us before he got sick was about not building a stupa [shrine for his remains] for him and putting his ashes in an urn for us to pray to. He strongly commanded us not to do this.

Eliza Barclay

What are some of the most important teachings from Buddhism about dying?

Phap Dung

We are aware that one day we are all going to deteriorate and die — our neurons, our arms, our flesh and bones. But if our practice and our awareness is strong enough, we can see beyond the dying body and pay attention also to the spiritual body. We continue through the spirit of our speech, our thinking, and our actions. These three aspects of body, speech, and mind continues.

In Buddhism, we call this the nature of no birth and no death. It is the other dimension of the ultimate. It’s not something idealized, or clean. The body has to do what it does, and the mind as well.

But in the ultimate dimension, there is continuation. We can cultivate this awareness of this nature of no birth and no death, this way of living in the ultimate dimension; then slowly our fear of death will lessen.

This awareness also helps us be more mindful in our daily life, to cherish every moment and everyone in our life.

One of the most powerful teachings that he shared with us before he got sick was about not building a stupa [shrine for his remains] for him and putting his ashes in an urn for us to pray to. He strongly commanded us not to do this.

I will paraphrase his message:

“Please do not build a stupa for me. Please do not put my ashes in a vase, lock me inside and limit who I am. I know this will be difficult for some of you. If you must build a stupa though, please make sure that you put a sign on it that says, ‘I am not in here.’ In addition, you can also put another sign that says, ‘I am not out there either,’ and a third sign that says, ‘If I am anywhere, it is in your mindful breathing and in your peaceful steps.’”

“Please do not build a stupa for me. Please do not put my ashes in a vase, lock me inside and limit who I am. I know this will be difficult for some of you. If you must build a stupa though, please make sure that you put a sign on it that says, ‘I am not in here.’ In addition, you can also put another sign that says, ‘I am not out there either,’ and a third sign that says, ‘If I am anywhere, it is in your mindful breathing and in your peaceful steps.’”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)