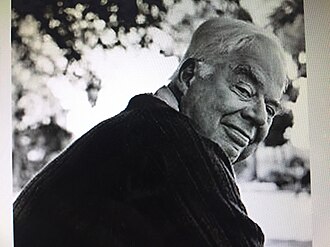

리처드 로티

Richard McKay Rorty | |

|---|---|

| |

신상정보 | |

| 출생 | 1931년 10월 4일 뉴욕 |

| 사망 | 2007년 6월 8일(75세) 캘리포니아주 팰러앨토 |

| 학력 | 시카고 대학교 (학사/석사) 예일 대학교 (박사) |

| 시대 | 20세기 철학 |

| 지역 | 서양 철학 |

| 학파 | 실용주의, 후기 분석철학 |

리처드 매케이 로티(Richard McKay Rorty: 1931년 10월 4일 – 2007년 6월 8일)는 미국의 철학자이다. 그는 길고 다양한 학자로서의 경력을 지녔다. 프린스턴 대학교에서 철학을 가르쳤고, 버지니아 대학교에서 인문학을 가르쳤으며, 스탠포드 대학교의 비교 문학 교수였다. 그는 이러한 복잡한 지적 배경을 지닌 덕분에 그가 나중에 자신에게 그 이름으로 딱지 붙이는 것을 거부했던 그 실용주의 철학에서 분석 철학의 전통을 좀 더 포괄적으로 이해할 수 있었다.

시카고 대학교와 예일 대학교에서 수학하였으며, 철학사와 현대 분석 철학에 관심을 갖고 공부하였다. 후자는 1960년대 프린스턴 대학교에서 그의 연구의 주된 관심을 차지하였다.[1] 로티는 지식이 표상으로부터 완전히 독립되어 있는 세계의 올바른 표상 즉, 자연의 거울을 포함한다는 철학적 전통을 거부하였다. 로티는 지식을 자연의 거울로 보는 생각이 서양 철학 전반에 만연해 있다고 보았다. 이러한 접근에 반하여 로티는 때로는 신실용주의 또는 네오프래그머티즘이라고 불리는 실용주의의 새로운 형태를 지지하였다. 이러한 과학적, 철학적 방법은 사회적 유용성에 의하여 사람들이 폐기하거나 적용하는 우연의 어휘들을 형성한다. 로티는 표상주의자의 설명을 거부하는 것이 그가 아이러니즘이라고 부르는 마음의 상태로 이끈다고 믿었다. 아이러니즘으로 사람들은 역사 속에서의 위치 또는 철학적 어휘의 우연성에 대해서 인식하게 된다.

영향

로티는 가장 폭넓게 논의되는 현대 철학자이자, 가장 논쟁적인 철학자 중의 한 명으로, 그의 저작은 존경받는 철학자 다수의 사상적 대응을 촉발시켰다. 예를 들어, 로버트 브랜덤의 선집, 《로티 앤드 히스 크리틱스》(Rorty and His Critics)에서 로티의 철학은 도널드 데이빗슨, 위르겐 하버마스, 힐러리 퍼트넘, 존 맥도웰, 데니얼 데닛에 의해 논의된다.

존 맥도웰은 로티, 특히 로티의 《철학 그리고 자연의 거울》로부터 강한 영향을 받았다. 대륙 철학에서는 위르겐 하버마스, 자크 데리다 등이 또 다른 방식으로 로티의 영향을 받았다. 미국의 소설가 데이비드 포스터 월리스는 자신의 선집에 실린 단편 하나에 〈철학 그리고 자연의 거울〉이라는 제목을 붙였으며, 비평가들은 월리스의 아이러니에 대한 몇 개의 저술이 로티의 영향이라고 평가한다.

주요 저서

- 《펄라서피 앤드 더 미러 오브 네이처》(Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature), 프린스턴 대학교 출판부, 1979년.

- 박지수 역, 《철학 그리고 자연의 거울》, 까치, 1998년

- 《칸서퀀시스 오브 프래그머티즘》(Consequences of Pragmatism), 미네소타 대학교 출판부, 1982년

- 김동식 역, 《실용주의의 결과》, 민음사, 1996년

- 《컨틴전시, 아이러니, 앤드 살리대러티》(Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity), 캠브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989년.

- 김동식 역, 《우연성 아이러니 연대성》, 민음사, 1996년.

- 《어치빙 아우어 컨트리》(Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth Century America), 하버드 대학교 출판부, 1998년.

- 임옥희 역, 《미국 만들기 - 20세기 미국에서의 좌파 사상》, 동문선, 2003년

관련 문헌

- 이유선, 《리처드 로티》 (누구나 철학 총서 1), 이룸, 2003년

- 이유선, 《아이러니스트의 사적인 진리》, 라티오, 2008년

- 이유선, 《듀이&로티》 (지식인마을 시리즈 9), 김영사, 2006년

- 이유선 외, 《로티의 철학과 아이러니》 (대우학술총서 610), 아카넷, 2014년

- 로티 『철학과 자연의 거울』 / 김희정 보관됨 2020-09-26 - 웨이백 머신 pdf

같이 보기

Richard Rorty | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Richard McKay Rorty October 4, 1931 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 8, 2007 (aged 75) Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Education | |

| Doctoral advisor | Paul Weiss |

| Other advisors | Rudolf Carnap Richard McKeon Charles Hartshorne |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Postanalytic philosophy[1] Neopragmatism[2] |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students | Robert Brandom Michael Williams |

| Main interests | |

| Notable ideas |

|

Richard McKay Rorty (October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher, historian of ideas, and public intellectual. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, Rorty's academic career included appointments as the Stuart Professor of Philosophy at Princeton University, the Kenan Professor of Humanities at the University of Virginia, and a professor of comparative literature at Stanford University. Among his most influential books are Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979), Consequences of Pragmatism (1982), and Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989).

Rorty rejected the long-held idea that correct internal representations of objects in the outside world are a necessary prerequisite for knowledge. Rorty argued instead that knowledge is an internal and linguistic affair; knowledge relates only to our own language.[4][5] Rorty argues that language is made up of vocabularies that are temporary and historical,[6] and concludes that "since vocabularies are made by human beings, so are truths".[7] The acceptance of the preceding arguments leads to what Rorty calls "ironism"; a state of mind where people are completely aware that their knowledge is dependent on their time and place in history, and are therefore somewhat detached from their own beliefs.[8] However, Rorty also argues that "a belief can still regulate action, can still be thought worth dying for, among people who are quite aware that this belief is caused by nothing deeper than contingent historical circumstance".[9]

Biography

Richard Rorty was born on October 4, 1931, in New York City.[10] His parents, James and Winifred Rorty, were activists, writers and social democrats. His maternal grandfather, Walter Rauschenbusch, was a central figure in the Social Gospel movement of the early 20th century.[11]

His father experienced two nervous breakdowns in his later life. The second breakdown, which he had in the early 1960s, was more serious and "included claims to divine prescience."[12] Consequently, Richard Rorty fell into depression as a teenager and in 1962 began a six-year psychiatric analysis for obsessional neurosis.[12] Rorty wrote about the beauty of rural New Jersey orchids in his short autobiography, "Trotsky and the Wild Orchids," and his desire to combine aesthetic beauty and social justice.[13] His colleague Jürgen Habermas's obituary for Rorty points out that Rorty's childhood experiences led him to a vision of philosophy as the reconciliation of "the celestial beauty of orchids with Trotsky's dream of justice on earth."[14] Habermas describes Rorty as an ironist:

Rorty enrolled at the University of Chicago shortly before turning 15, where he received a bachelor's and a master's degree in philosophy (studying under Richard McKeon),[15][16] continuing at Yale University for a PhD in philosophy (1952–1956).[17] He married another academic, Amélie Oksenberg (Harvard University professor), with whom he had a son, Jay Rorty, in 1954. After two years in the U.S. Army, he taught at Wellesley College for three years until 1961.[18] Rorty divorced his wife and then married Stanford University bioethicist Mary Varney in 1972. They had two children, Kevin and Patricia, now Max. While Richard Rorty was a "strict atheist" (Habermas),[14] Mary Varney Rorty was a practicing Mormon.[12]

Rorty was a professor of philosophy at Princeton University for 21 years.[18] In 1981, he was a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, commonly known as the "Genius Grant", in its first year of awarding, and in 1982 he became Kenan Professor of the Humanities at the University of Virginia, working closely with colleagues and students in multiple departments, especially in English.[19] In 1998 Rorty became professor of comparative literature (and philosophy, by courtesy), at Stanford University, where he spent the remainder of his academic career.[19] During this period he was especially popular, and once quipped that he had been assigned to the position of "transitory professor of trendy studies."[20]

Rorty's doctoral dissertation, The Concept of Potentiality was a historical study of the concept, completed under the supervision of Paul Weiss, but his first book (as editor), The Linguistic Turn (1967), was firmly in the prevailing analytic mode, collecting classic essays on the linguistic turn in analytic philosophy. However, he gradually became acquainted with the American philosophical movement known as pragmatism, particularly the writings of John Dewey. The noteworthy work being done by analytic philosophers such as Willard Van Orman Quine and Wilfrid Sellars caused significant shifts in his thinking, which were reflected in his next book, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979).

Pragmatists generally hold that the meaning of a proposition is determined by its use in linguistic practice. Rorty combined pragmatism about truth and other matters with a later Wittgensteinian philosophy of language, which declares that meaning is a social-linguistic product, and sentences do not "link up" with the world in a correspondence relation. Rorty wrote in Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989):

Views like this led Rorty to question many of philosophy's most basic assumptions—and also led to his being apprehended as a postmodern/deconstructionist philosopher. Indeed, from the late 1980s through the 1990s, Rorty focused on the continental philosophical tradition, examining the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard and Jacques Derrida. His work from this period includes Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989), Essays on Heidegger and Others: Philosophical Papers II (1991), and Truth and Progress: Philosophical Papers III (1998). The latter two works attempt to bridge the dichotomy between analytic and continental philosophy by claiming that the two traditions complement rather than oppose each other.

According to Rorty, analytic philosophy may not have lived up to its pretensions and may not have solved the puzzles it thought it had. Yet such philosophy, in the process of finding reasons for putting those pretensions and puzzles aside, helped earn itself an important place in the history of ideas. By giving up on the quest for apodicticity and finality that Edmund Husserl shared with Rudolf Carnap and Bertrand Russell, and by finding new reasons for thinking that such quest will never succeed, analytic philosophy cleared a path that leads past scientism, just as the German idealists cleared a path that led around empiricism.

In the last fifteen years of his life, Rorty continued to publish his writings, including Philosophy as Cultural Politics (Philosophical Papers IV), and Achieving Our Country (1998), a political manifesto partly based on readings of Dewey and Walt Whitman in which he defended the idea of a progressive, pragmatic left against what he felt were defeatist, anti-liberal, anti-humanist positions espoused by the critical left and continental school. Rorty felt these anti-humanist positions were personified by figures like Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Foucault. Such theorists were also guilty of an "inverted Platonism" in which they attempted to craft overarching, metaphysical, "sublime" philosophies—which in fact contradicted their core claims to be ironist and contingent.

According to Eduardo Mendieta "Rorty described himself as a 'postmodern bourgeois liberal', even if he also attacked the academic left, though not for being anti-truth, but for being unpatriotic. Rorty’s Zen attitude about truth could easily be confused for a form of political relativism—a Machiavellian type of politics."[21]

Rorty's last works, after his move to Stanford University concerned the place of religion in contemporary life, liberal communities, comparative literature and philosophy as "cultural politics."

Shortly before his death, he wrote a piece called "The Fire of Life" (published in the November 2007 issue of Poetry magazine)[22] in which he meditates on his diagnosis and the comfort of poetry. He concludes:

On June 8, 2007, Rorty died in his home from pancreatic cancer.[17][19][23]

Major works

Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

In Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979), Rorty argues that the history of philosophy is the history of the quest to make sense of the claim that the mind has knowledge of an objective reality, and thus to give philosophy the ability to judge other aspects of culture as being in or out of touch with this reality. He dubs this idea "representationalism" and refers to it using the metaphor of the "mirror of nature", hence the title of the book.

In the introduction, Rorty claims that Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and John Dewey are the three most important philosophers of the 20th century; Wittgenstein for his diagnosis of philosophy as a set of linguistic confusions, Heidegger for his historical deconstruction of such confusions, and Dewey for his hopeful prognosis of a post-metaphysical culture. In continuing this quietist and historicist tradition, the book is therapeutic rather than constructive in nature. However, Rorty aims to carry out his therapy by using the arguments of such systematic philosophers as W. V. O. Quine, Wilfrid Sellars, Thomas Kuhn, and Donald Davidson in order to undermine our philosophical intuitions about the mind (mirror), knowledge (mirroring), and philosophy itself (the study of mirroring), and thus to undermine the representationalist picture of the "mirror of nature".

Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity

In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989), Rorty argues that there is no worthwhile theory of truth, aside from the non-epistemic semantic theory Davidson developed (based on the work of Alfred Tarski).[24] Rorty also suggests that there are two kinds of philosophers: those occupied with private matters and those occupied with public matters. Private philosophers, who provide one with greater abilities to (re)create oneself (a view adapted from Nietzsche,[25] and which Rorty identifies with the novels of Marcel Proust and Vladimir Nabokov), should not be expected to help with public problems. For a public philosophy, one might instead turn to philosophers like Rawls or Habermas,[26] even though, according to Rorty, the latter is a "liberal who doesn't want to be an ironist".[27] While Habermas believes that his theory of communicative rationality constitutes an update of rationalism, Rorty thinks that the latter and any "universal" pretensions should be totally abandoned.[28]

This book also marks his first attempt to specifically articulate a political vision consistent with his philosophy, the vision of a diverse community bound together by opposition to cruelty, and not by abstract ideas such as "justice" or "common humanity." Consistent with his anti-foundationalism, Rorty states that there is "no noncircular theoretical backup for the belief that cruelty is horrible."[29]

Rorty also introduces the terminology of ironism, which he uses to describe his mindset and his philosophy. Rorty describes the ironist as a person who "worries that the process of socialization which turned her into a human being by giving her a language may have given her the wrong language, and so turned her into the wrong kind of human being. But she cannot give a criterion of wrongness."[30]

Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth

Rorty describes the project of this essay collection as trying to "offer an antirepresentationalist account of the relation between natural science and the rest of culture."[31] Amongst the essays in Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth: Philosophical Papers, Volume 1 (1990), is "The Priority of Democracy to Philosophy," in which Rorty defends Rawls against communitarian critics. Rorty argues that liberalism can "get along without philosophical presuppositions," while at the same time conceding to communitarians that "a conception of the self that makes the community constitutive of the self does comport well with liberal democracy."[32] Moreover, for Rorty Rawls could be compared to Habermas, a sort of United States' Habermas, with E. Mendieta's words: "An Enlightenment figure who thought that all we have is communicative reason and the use of public reason, two different names for the same thing—the use of reason by a public for the purpose of deciding how to live collectively and what aims should be the goal of the public good".[21] For Rorty, social institutions ought to be thought of as "experiments in cooperation rather than as attempts to embody a universal and ahistorical order."[33]

Essays on Heidegger and Others

In this text, Rorty focuses primarily on the continental philosophers Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida. He argues that these European "post-Nietzscheans" share much with American pragmatists, in that they critique metaphysics and reject the correspondence theory of truth.[34] Taking up and developing what he had argued in previous works,[35] Rorty claims that Derrida is most useful when viewed as a funny writer who attempted to circumvent the Western philosophical tradition, rather than the inventor of a philosophical (or literary) "method". In this vein, Rorty criticizes Derrida's followers like Paul de Man for taking deconstructive literary theory too seriously.

Achieving Our Country

In Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America (1998), Rorty differentiates between what he sees as the two sides of the Left, a cultural Left and a progressive Left. He criticizes the cultural Left, which is exemplified by post-structuralists such as Foucault and postmodernists such as Lyotard, for offering critiques of society, but no alternatives (or alternatives that are so vague and general as to be abdications). Although these intellectuals make insightful claims about the ills of society, Rorty suggests that they provide no alternatives and even occasionally deny the possibility of progress. On the other hand, the progressive Left, exemplified for Rorty by the pragmatist John Dewey, Whitman and James Baldwin, makes hope for a better future its priority. Without hope, Rorty argues, change is spiritually inconceivable and the cultural Left has begun to breed cynicism. Rorty sees the progressive Left as acting in the philosophical spirit of pragmatism. The book's passage about of the rise of an authoritarian "strongman" who will ensure that the "smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots" has been described as prophetic of Donald Trump's rise to political power.[36][37][38]

On human rights

Rorty's notion of human rights is grounded on the notion of sentimentality. He contended that throughout history humans have devised various means of construing certain groups of individuals as inhuman or subhuman. Thinking in rationalist (foundationalist) terms will not solve this problem, he claimed. Rorty advocated the creation of a culture of global human rights in order to stop violations from happening through a sentimental education. He argued that we should create a sense of empathy or teach empathy to others so as to understand others' suffering.[39]

On hope

Rorty advocates for what philosopher Nick Gall characterizes as a "boundless hope" or type of "melancholic meliorism." According to this view, Rorty replaces foundationalist hopes for certainty with those of perpetual growth and constant change, which he believes enables us to send conversation and hopes in new directions we currently can't imagine.[40]

Rorty articulates this boundless hope in his 1982 book Consequences of Pragmatism,[41] where he applies his framework of wholesale hope versus retail hope. Herein he says, "Let me sum up by offering a third and final characterization of pragmatism: It is the doctrine that there are no constraints on inquiry save conversational ones—no wholesale constraints derived from the nature of the objects, or of the mind, or of language, but only those retail constraints provided by the remarks of our fellow inquirers."

Reception and criticism

Rorty is among the most widely discussed and controversial contemporary philosophers,[18] and his works have provoked thoughtful responses from many other well-respected figures in the field. In Robert Brandom's anthology Rorty and His Critics, for example, Rorty's philosophy is discussed by Donald Davidson, Jürgen Habermas, Hilary Putnam, John McDowell, Jacques Bouveresse, and Daniel Dennett, among others.[42] In 2007, Roger Scruton wrote, "Rorty was paramount among those thinkers who advance their own opinion as immune to criticism, by pretending that it is not truth but consensus that counts, while defining the consensus in terms of people like themselves."[43] Ralph Marvin Tumaob concludes that Rorty was influenced by Jean-François Lyotard's metanarratives, and added that "postmodernism was influenced further by the works of Rorty".[44]

McDowell is strongly influenced by Rorty, particularly Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979).[45] In continental philosophy, authors such as Jürgen Habermas, Gianni Vattimo, Jacques Derrida, Albrecht Wellmer, Hans Joas, Chantal Mouffe, Simon Critchley, Esa Saarinen, and Mike Sandbothe are influenced in different ways by Rorty's thinking. American novelist David Foster Wallace titled a short story in his collection Oblivion: Stories "Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature," and critics have identified Rorty's influence in some of Wallace's writings on irony.[46]

Susan Haack has been a fierce critic of Rorty's neopragmatism. Haack criticises Rorty's claim to be a pragmatist at all and wrote a short play called We Pragmatists, where Rorty and Charles Sanders Peirce have a fictional conversation using only accurate quotes from their own writing. For Haack, the only link between Rorty's neopragmatism and Peirce's pragmatism is the name. Haack believes Rorty's neopragmatism is anti-philosophical and anti-intellectual, and exposes people further to rhetorical manipulation.[18][47][48]

Although Rorty was an avowed liberal, his political and moral philosophies have been attacked by commentators from the Left, some of whom believe them to be insufficient frameworks for social justice.[49] Rorty was also criticized for his rejection of the idea that science can depict the world.[50] One criticism, especially of Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, is that Rorty's philosophical hero, the ironist, is an elitist figure.[51] Rorty argues that most people would be "commonsensically nominalist and historicist" but not ironist. They would combine an ongoing attention to the particular as opposed to the transcendent (nominalism) with an awareness of their place in a continuum of contingent lived experience alongside other individuals (historicist), without necessarily having continual doubts about the resulting worldview as the ironist does. An ironist is someone who "has radical and continuing doubts about their final vocabulary", that is "a set of words which they [humans] employ to justify their actions, their beliefs, and their lives"; "realizes that argument phrased in their vocabulary can neither underwrite nor dissolve these doubts"; and "does not think their vocabulary is closer to reality than others".[52] On the other hand, the Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo and the Spanish philosopher Santiago Zabala in their 2011 book Hermeneutic Communism: from Heidegger to Marx affirm that

Rorty often draws on a broad range of other philosophers to support his views, and his interpretation of their work has been contested.[18] Since he is working from a tradition of reinterpretation, he is not interested in "accurately" portraying other thinkers, but rather in using it in the same way a literary critic might use a novel. His essay "The Historiography of Philosophy: Four Genres" is a thorough description of how he treats the greats in the history of philosophy. In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Rorty attempts to disarm those who criticize his writings by arguing that their philosophical criticisms are made using axioms that are explicitly rejected within Rorty's own philosophy.[54] For instance, he defines allegations of irrationality as affirmations of vernacular "otherness", and so—Rorty argues—accusations of irrationality can be expected during any argument and must simply be brushed aside.[55]

Awards and honors

- 1973: Guggenheim Fellowship[56]

- 1981: MacArthur Fellowship[19]

- 1983: Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[57]

- 2005: Elected to the American Philosophical Society[58]

- 2007: The Thomas Jefferson Medal, awarded by the American Philosophical Society[59]

Select bibliography

- As author

- Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Consequences of Pragmatism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0816610631

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0521353816

- Philosophical Papers vols. I–IV:

- Objectivity, Relativism and Truth: Philosophical Papers I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521353694

- Essays on Heidegger and Others: Philosophical Papers II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Truth and Progress: Philosophical Papers III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Philosophy as Cultural Politics: Philosophical Papers IV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Mind, Language, and Metaphilosophy: Early Philosophical Papers Eds. S. Leach and J. Tartaglia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1107612297.

- Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth Century America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0674003118

- Philosophy and Social Hope. New York: Penguin, 2000.

- Against Bosses, Against Oligarchies: A Conversation with Richard Rorty. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2002.

- The Future of Religion with Gianni Vattimo Ed. Santiago Zabala. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0231134941

- An Ethics for Today: Finding Common Ground Between Philosophy and Religion. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0231150569

- What's the Use of Truth? with Pascal Engel, transl. by William McCuaig, New York: Columbia University Press, 2007 ISBN 9780231140140

- On Philosophy and Philosophers: Unpublished papers 1960-2000, Ed. by W. P. Małecki and Chris Voparil, Cambridge University Press 2020 ISBN 9781108488457

- Pragmatism as Anti-Authoritarianism, Ed. E. Mendieta, foreword by Robert B. Brandom, Harvard UP 2021, ISBN 9780674248915

- What Can We Hope For? Essays on Politics, Ed. by W. P. Małecki and Chris Voparil, Princeton University Press 2022 ISBN 9780691217529

- As editor

- The Linguistic Turn, Essays in Philosophical Method, (1967), edited by Richard M. Rorty, University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0226725697 (an introduction and two retrospective essays)

- Philosophy in History. edited by Richard M. Rorty, J. B. Schneewind, and Quentin Skinner, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985 (an essay by Richard M. Rorty, "Historiography of Philosophy", pp. 29–76)

See also

- Instrumentalism

- List of American philosophers

- List of liberal theorists

- List of thinkers influenced by deconstruction

Notes

- Metaphilosophy – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Pragmatism – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Richard Rorty (1931—2007) – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Robert Brandom summarizes Rorty's anti-representationalism: "In a nutshell, this is how I think Rorty's critique of semantic representationalism goes: Normative relations are exclusively intravocabulary. Extravocabulary relations are exclusively causal. Representation purports to be both a normative relation, supporting assessments of correctness and incorrectness, and a relation between representings within a vocabulary and representeds outside of that vocabulary. Therefore, the representational model of the relation of vocabularies to their environment should be rejected." Brandom, Robert (October 11, 2000). Vocabularies of Pragmatism: Synthesizing Naturalism and Historicism. (In: Rorty and His Critics). Malden, Mass. p. 160. ISBN 0-631-20981-6. OCLC 43109795.

- Rorty distinguished between knowledge-that and knowledge-how; only language users can have knowledge-that (epistemically valid knowledge) while all life forms, including bacteria and virus, can have "knowledge-how" (know-how). Rorty, Richard (October 11, 2000). Response to Barry Allen. (In: Rorty and His Critics). Malden, Mass. pp. 238–239. ISBN 0-631-20981-6. OCLC 43109795.

- Rorty, Richard (1982). Consequences of Pragmatism: Essays, 1972-1980. Minneapolis. p. 158. ISBN 0-8166-1064-9. OCLC 8222790.

- Rorty, Richard (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge. pp. 6, 21. ISBN 0-521-35381-5. OCLC 18290785.

The world can, once we have programmed ourselves with a language, cause us to hold beliefs. But it cannot propose a language for us to speak. Only other human beings can do that. [...] [S]ince truth is a property of sentences, since sentences are dependent for their existence upon vocabularies, and since vocabularies are made by human beings, so are truths.

- "The ironist spends her time worrying about the possibility that she has been initiated into the wrong tribe, taught to play the wrong language game. She worries that the process of socialization which turned her into a human being by giving her a language may have given her the wrong language, and so turned her into the wrong kind of human being. But she cannot give a criterion of wrongness. So, the more she is driven to articulate her situation in philosophical terms, the more she reminds herself of her rootlessness by constantly using terms like Weltanschauung, 'perspective', dialectic, conceptual framework, 'historical epoch', language game, 'redescription', 'vocabulary' and 'irony'." Rorty, Richard (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge. p. 75. ISBN 0-521-35381-5. OCLC 18290785.

- Rorty, Richard (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge. p. 189. ISBN 0-521-35381-5. OCLC 18290785.

- "Richard Rorty: The Making of an American Philosopher". press.uchicago.edu. October 4, 1931. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- Bernstein, Adam (June 11, 2007). "Richard Rorty, 75; Leading U.S. Pragmatist Philosopher". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- Bruce Kuklick. "Neil Gross, Richard Rorty: The Making of an American Philosopher." Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 47.1 (2011):36.

- Casey Nelson Blake, "Private Life and Public Commitment: From Walter Rauschenbusch to Richard Rorty," in A Pragmatist's Progress?: Richard Rorty and American Intellectual History, ed. John Pettegrew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), 85. ISBN 9780847690626

- "Jürgen Habermas: Philosopher, poet and friend (12/06/2007)". signandsight. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- Marchetti, Giancarlo. "Interview with Richard Rorty." Philosophy Now Volume 43, Oct.–Nov. 2003.

- Ryerson, James. "The Quest for Uncertainty: Richard Rorty's Pragmatic Pilgrimage" Linguafranca Vol. 10, No. 9. December 2000/January 2001.

- "Richard Rorty, distinguished public intellectual and controversial philosopher, dead at 75" (Stanford's announcement), June 10, 2007

- Ramberg, Bjørn (August 1, 2009). "Richard Rorty". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Richard Rorty, Philosopher, Dies at 75" (NY Times Obituary), June 11, 2007

- Ryerson, James. "Essay: Thinking Cheerfully." The New York Times Book Review. July 22, 2007: p. 27.

- Mendieta, Eduardo (July 22, 2017). "Rorty and Post-Post Truth". lareviewofbooks. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- Rorty, Richard (November 2007). "The Fire of Life". Poetry Magazine.

- "Richard Rorty," (short obituary), June 9, 2007.

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. pp. 11-22. ISBN 978-0521353816

- Rorty argues that Nietzsche was the first philosopher to propose to totally abandon the concept of objective truth. For Nietzsche human beings should draw consolation not simply by trying to rise from the condition of pure animality, but by the awareness of having "self-created". Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. pp. 23-43. ISBN 978-0521353816

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. pp. 56-70. ISBN 978-0521353816

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 61. ISBN 978-0521353816

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 68. ISBN 978-0521353816

- Rorty, R.; Rorty, P.C.L.R.; Cambridge University Press; Richard, R. (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Clark lectures. Cambridge University Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-521-36781-3. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- Rorty, R.; Rorty, P.C.L.R.; Cambridge University Press; Richard, R. (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Clark lectures. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-521-36781-3. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth: Philosophical Papers, Volume 1 (1990), p. I

- Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth: Philosophical Papers, Volume 1 (1990), p. 179

- Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth: Philosophical Papers, Volume 1 (1990), p. 196

- Essays on Heidegger and Others: Philosophical Papers II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. pp. 122-135. ISBN 978-0521353816

- Mathis-Lilley, Ben (November 11, 2016). "The Philosopher Who Predicted Trump in 1998 Also Predicted His First Act as President-Elect". Slate. Retrieved April 23, 2025.

- Senior, Jennifer (November 21, 2016). "Richard Rorty's 1998 Book Suggested Election 2016 Was Coming". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2025.

- Helmore, Edward (November 19, 2016). "'Something will crack': supposed prophecy of Donald Trump goes viral". The Guardian. Retrieved April 23, 2025.

- See Barreto, José-Manuel. "Rorty and Human Rights: Contingency, Emotions and How to Defend Human Rights Telling Stories." Utrecht Law Review, Volume 7 Issue 2 April 2011

- Gall, Nick. "Dewey and Rorty: Sending Pragmatist Hopes in New Directions." November, 2022, Erraticus[1].

- Rorty, Richard (1982). Consequences of Hope. University of Minnesota Press.,

- Brandom, Robert B. (October 3, 2000). Rorty and His Critics. Wiley. ISBN 0631209824.

- Scruton, Roger (June 12, 2007). "Richard Rorty's legacy". openDemocracy. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- "Rorty's Philosophy & the Mirror of Nature (pdf)". October 18, 2016.

- In the preface to Mind and World (pp. ix–x) McDowell writes, "it will be obvious that Rorty's work is ... central for the way I define my stance here".

- Howard, Jennifer. "The Afterlife of David Foster Wallace". Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Susan Haack (November 1997). "Vulgar Rortyism". New Criterion.

- Haack, Susan (1993). "Ch. 9: Vulgar Pragmatism: an Unedifying Prospect". Evidence and Inquiry. Oxford UK: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631118510. OL 1398949M.

- "Objectivity and Action: Wal-Mart and the Legacy of Marx and Nietzsche", A discussion of Terry Eagleton's attacks on Rorty's philosophy as insufficient in the fight against corporations such as Wal-Mart

- "The failure to recognize science's particular powers to depict reality, Daniel Dennett wrote, shows 'flatfooted ignorance of the proven methods of scientific truth-seeking and their power.'"[2]

- "Rob Reich – The Paradoxes of Education in Rorty's Liberal Utopia". Archived from the original on June 15, 2006.

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 73 ISBN 978-0521353816

- Gianni Vattimo and Santiago Zabala. Hermeneutic Communism: From Heidegger to Marx Columbia University Press. 2011. Pp. 2–3

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 44 ISBN 978-0521353816

- Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 48 ISBN 978-0521353816

- "Richard M. Rorty". www.gf.org. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "Richard McKay Rorty". www.amacad.org. American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- "2007 Thomas Jefferson Medal". American Philosophical Society. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

Further reading

- Chris Voparil, Reconstructing Pragmatism: Richard Rorty and the Classical Pragmatists, 2022

- David Rondel, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Rorty, 2021

- Randall Auxier, Eli Kramer, Krzysztof Piotr Skowroński, eds., Rorty and Beyond, 2019

- Ulf Schulenberg, Romanticism and Pragmatism: Richard Rorty and the Idea of a Poeticized Culture, 2015

- Krzysztof Piotr Skowroński, Values, Valuations, and Axiological Norms in Richard Rorty's Neopragmatism, 2015

- Marianne Janack, What We Mean By Experience, 2012

- Marianne Janack, editor, Feminist Interpretations of Richard Rorty, 2010

- James Tartaglia, Richard Rorty: Critical Assessments, 4 vols., 2009

- Neil Gross, Richard Rorty: The Making of an American Philosopher, 2008

- Gross, Neil. 2019. Richard Rorty: the Making of an American Philosopher. University of Chicago Press.

- Rorty's Politics of Redescription / Gideon Calder, 2007

- Rorty and the Mirror of Nature / James Tartaglia, 2007

- Richard Rorty: Pragmatism and Political Liberalism / Michael Bacon, 2007

- Richard Rorty: politics and vision / Christopher Voparil, 2006

- Richard Rorty: his philosophy under discussion / Andreas Vieth, 2005

- Richard Rorty / Charles B Guignon., 2003

- Rorty / Gideon Calder, 2003

- Richard Rorty's American faith / Taub, Gad Shmuel, 2003

- The ethical ironist: Kierkegaard, Rorty, and the educational quest / Rohrer, Patricia Jean, 2003

- Doing philosophy as a way to individuation: Reading Rorty and Cavell / Kwak, Duck-Joo, 2003

- Richard Rorty / Alan R Malachowski, 2002

- Richard Rorty: critical dialogues / Matthew Festenstein, 2001

- Richard Rorty: education, philosophy, and politics / Michael Peters, 2001

- Rorty and his critics / Robert Brandom, 2000

- On Rorty / Richard Rumana, 2000

- Philosophy and freedom: Derrida, Rorty, Habermas, Foucault / John McCumber, 2000

- A pragmatist's progress?: Richard Rorty and American intellectual history / John Pettegrew, 2000

- Problems of the modern self: Reflections on Rorty, Taylor, Nietzsche, and Foucault / Dudrick, David Francis, 2000

- The last conceptual revolution: a critique of Richard Rorty's political philosophy / Eric Gander, 1999

- Richard Rorty's politics: liberalism at the end of the American century / Markar Melkonian, 1999

- The work of friendship: Rorty, his critics, and the project of solidarity / Dianne Rothleder, 1999

- For the love of perfection: Richard Rorty and liberal education / René Vincente Arcilla, 1995

- Rorty & pragmatism: the philosopher responds to his critics / Herman J Saatkamp, 1995

- Richard Rorty: prophet and poet of the new pragmatism / David L Hall, 1994

- Reading Rorty: critical responses to Philosophy and the mirror of nature (and beyond) / Alan R Malachowski, 1990

- Rorty's humanistic pragmatism: philosophy democratized / Konstantin Kolenda, 1990

External links

Quotations related to Richard Rorty at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Richard Rorty at Wikiquote Media related to Richard Rorty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Richard Rorty at Wikimedia Commons- UCIspace @ the Libraries digital collection: Richard Rorty born digital files, 1988–2003

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Rorty audio, "Dewey and Posner on Pragmatism and Moral Progress," University of Chicago Law School, April 14, 2006.

- PhilWeb's entry for Richard Rorty An exhaustive compilation of on-line links and off-line sources.

- Rorty essays published in Dissent (magazine)

- Rorty audio, informative interview by Prof. Robert P. Harrison, Nov. 22, 2005.

- Rorty interview, "Against Bosses, Against Oligarchies," conducted by Derek Nystrom & Kent Puckett, Prickly Paradigm Press, Sept. 1998.

- Rorty interview, The Atlantic Monthly, April 23, 1998.

- Rorty Memorial Lecture by Jürgen Habermas, Stanford University, Nov. 2, 2007.

- Rorty eulogized by Richard Posner, Brian Eno, Mark Edmundson, Jürgen Habermas, Daniel Dennett, Stanley Fish, David Bromwich, Simon Blackburn, Morris Dickstein & others, Slate Magazine, June 18, 2007.

- "The Inspiring Power of the Shy Thinker: Richard Rorty" by Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Telos, June 13, 2007.

- Richard Rorty at Princeton: Personal Recollections by Raymond Geuss in Arion, Winter 2008

- Rereading Rorty by Albrecht Wellmer in Krisis, 2008.

- Richard Rorty at IMDb

리차드 로티

| |

| 탄생 | 1931년 10월 4 일 미국 뉴욕 |

|---|---|

| 사망 | 2007년 6월 8일 (75세몰) 미국 팔로 알토 ( 캘리포니아 주) |

| 연대 | 20세기 철학 |

| 지역 | 서양 철학 |

| 학교 | 플러그 마티즘 , 포스트 분석 철학 |

| 연구분야 | 인식론 , 언어 철학 , 마음의 철학 , 윤리학 , 메타 철학 , 형이상학 , 자유주의 , 포스트 모더니즘 |

| 주요 개념 | 포스트 철학, 아이러니 , 종극의 어휘, 인식론적 행동주의, 반표상 주의 |

리처드 맥케이 로티 ( 영 : Richard McKay Rorty , 1931년 10월 4일 - 2007년 6월 8일 )는 미국 의 철학자이자 사상사가 이다. 시카고대학 과 대학 에서 교육을 받았으며, 로티의 학술경력에는 프린스턴대학 의 스튜어트 철학교수, 버지니아대학 의 , 스탠포드대학 의 비교문학 교수로 임명이 포함 된다. 그의 가장 영향력 있는 저서에는 ' 철학과 자연의 거울 '(1979년), '플러그마티즘의 귀결'(1982년), ' 우연성·아이로니·연대 '(1989년)가 있다.

로티는 외계 대상의 올바른 내적 표상이 지식의 필요조건이라는 오랜 세월 유지되어 온 생각을 부정했다. 대신 로티는 지식은 "내적"이고 "언어적"일 것이며 지식은 우리 자신의 언어에만 관련된다고 주장했다 [ 1 ] [ 2 ] . 로티는 언어는 일시적이고 역사적인 어휘 로 구성되어 있다고 논하고 [ 3 ] , “어휘는 인간에 의해 만들어지기 때문에 진리 도 인간에 의해 만들어진다”고 결론지었다 [ 4 ] . 이러한 논의의 수용은 로티가 「아이 로니즘 」이라고 부르는 것으로 이어진다. 이것은 사람들이 자신의 지식이 역사적인 시간과 장소에 의존한다는 것을 완전히 인식하고, 그러므로 자신의 신념에서 다소 초연한 심적 상태이다 [ 5 ] . 그러나 로티는 또한 "신념은 그 신념이 우연한 역사적 상황 이외의 어떤 것에도 기인하지 않는다는 것을 충분히 인식하고 있는 사람들 사이에서도 행동을 규제하고 죽을 가치가 있다고 생각할 수 있다"고도 논하고 있다 [ 6 ] .

경력

리처드 로티는 1931년 10월 4일 뉴욕시에서 태어났다 [ 7 ] . 부모의 제임스 와 위니프레드 로티는 활동가, 작가, 사회민주주의자였다. 어머니의 할아버지 인 월터 라우셴 부시 는 20세기 초의 사회적 복음 운동의 중심적 인물이었다 [ 8 ] .

그의 아버지는 나중에 두 번의 영적 붕괴를 경험했습니다. 1960 년대 초반의 두 번째 붕괴는 더 심각했고 "신적 예지의 주장을 포함했다" [ 9 ] . 그 결과, 리처드 로티는 10대에 우울증에 빠졌고, 1962년에 강박신경증을 위해 6년간의 정신분석을 개시했다 [ 9 ] . 로티는 짧은 자전 ' 트로츠키 와 야생의 런'으로 뉴저지 주 시골의 런의 아름다움과 미적인 아름다움과 사회 정의를 결합시키고 싶다는 그의 욕망에 대해 썼다 [ 10 ] . 그의 동료인 유르겐 하버머스 의 로티에 대한 추모문은 로티의 어린 시절의 경험이 '런의 천상의 아름다움과 트로츠키의 지상의 정의의 꿈의 조화'라는 철학의 비전으로 이끌어졌다는 것을 지적하고 있다 [ 11 ] . 하버머스는 로티를 아이로니스트로 묘사한다: “아이로니스트인 로티에게는 신성한 것은 없다 . 사람들 은 젊은 헤겔을 연상케 하는 말로 대답했다. “내 거룩한 것의 감각은 언젠가 나의 먼 후손들이 사랑이 거의 유일한 법인 지구 규모의 문명 속에서 살 것이다는 희망과 연결되어 있다” [ 11 ] ".

로티는 15세가 되기 직전에 시카고 대학 에 입학하고, 거기서( 리처드 맥키 온 하에서 배운다) 철학 의 학사 학위와 석사 학위 를 취득하고 [ 12 ] [ 13 ] , 예일 대학 에서 철학의 박사 학위(1952 년 -1956년 ) 그는 같은 학자 아멜리 옥센버그 ( 하버드 대학교 교수)와 결혼하고 1954년 아들의 제이 로티를 벌었다. 미국 육군 에서 2년간 근무한 후, 1961년까지 3년간 웰즐리 대학 에서 교편을 취했다 [ 15 ] . 로티는 아내와 이혼하고 1972년 스탠포드 대학 의 생명윤리학자인 메리 버니와 재혼했다. 그들에게는 케빈과 패트리샤(현재 맥스)라는 두 아이가 있었다. 리처드 로티가 '엄격한 무신론자'(하버머스) [ 11 ] 인 반면, 메리 버니 로티는 실천적인 몰몬교 도 였다 [ 9 ] .

로티는 21년간 프린스턴 대학 의 철학 교수를 맡았다 [ 15 ] . 1981년, 그는 첫 시상년에 '천재 조성금'으로 알려진 맥아더 휄로우십을 수상 하고, 1982년에 버지니아 대학 의 키난 인문학 교수가 되어, 특히 영어 학부의 동료나 학생과 밀접하게 협력했다 [ 16 ] . 1998 년 로티는 스탠포드 대학 의 비교 문학 교수 (및 철학의 객원 교수)가되어 거기서 나머지 학술 생활을 보냈다 [ 16 ] . 이 기간 동안 그는 특히 인기가 있으며 자신을 "유행 연구의 일시적 교수"로 임명되었다고 농담을 말한 적도있다 [ 17 ] .

로티의 박사논문 ' 가능성 의 개념'은 폴 와이스 의 지도 아래 완성된 개념의 역사적 연구였지만, 그의 첫 저서(편자로서)인 '언어론적 전회'(1967년)는 분석철학 에서 언어론적 전회 에 관한 고전적인 논문을 모은 당시 지식이다. 그러나 그는 서서히 플러그 마티즘으로 알려진 미국의 철학 운동, 특히 존 듀이 의 저작에 친숙하게 되었다. 윌라드 반 오만 콰인과 윌프리드 셀러스 와 같은 분석 철학자들에 의해 만들어진 주목할 만한 연구는 그의 생각에 중요한 변화를 가져왔으며, 그것은 다음 저서 ' 철학과 자연의 거울 '(1979년)에 반영되었다.

플러그 마티스트 들은 일반적으로 명제의 의미가 그 언어적 실천에서의 사용에 의해 결정된다고 생각한다. 로티는 진리 및 기타 사항에 대한 플러그 매티즘을 위트겐슈타인 의 후기 언어 철학과 결합했다. 이 철학은 의미 는 사회언어적 산물이며, 문장은 대응관계에서 세계와 '연결'하지 않는다고 선언한다. 로티는 “우연성·아이로니·연대”(1989년)에서 다음과 같이 썼다.

진리는 외부에 있을 수 없다—인간의 마음으로부터 독립적으로 존재할 수 없다—왜냐하면 문장은 그렇게 존재하거나 외부에 있을 수 없기 때문이다. 세계는 외부에 있지만 세계의 설명은 외부에는 없다. 세계의 설명만이 참 또는 거짓이 될 수 있다. 인간의 기술활동에 도움이 되지 않는 세계 그 자체에는 그런 일이 불가능하다. (5페이지)

이러한 견해는 로티가 철학의 가장 기본적인 전제 중 많은 부분을 의문시 하게 되었다 . 실제로 1980년대 후반부터 1990년대에 걸쳐 로티는 대륙철학 의 전통에 초점을 맞추고 프리드리히 니체 , 마르틴 하이데거 , 미셸 푸코, 장 프란소와 리오타르 , 잭 데리다 의 작품 을 검토했다. 이 시기의 저작에는 '우연성·아이로니·연대'(1989년), '하이데거와 기타 사람들에 대한 논문:철학 논문 II'(1991년), '진리와 진보: 철학 논문 III'(1998년)이 있다. 후자의 두 작품은 두 전통이 대립하는 것이 아니라 보완한다고 주장함으로써 분석 철학과 대륙 철학의 이분법을 가교하려고 시도하고 있다.

로티에 따르면 분석 철학은 그 자부심에 맞지 않고 자신이 해결했다고 생각했던 퍼즐을 해결하지 못했을지도 모른다. 그러나 이러한 자부심과 퍼즐을 옆으로 두는 이유를 찾는 과정에서이 철학은 사상사에서 중요한 위치를 얻는 데 도움이되었습니다. 에트문트 후사르 가 루돌프 칼냅 과 버틀랜드 러셀 과 공유했던 필증 적 확실성과 최종성 탐구를 포기하고, 그러한 탐구가 결코 성공하지 못한다고 생각하는 새로운 이유를 발견함으로써 분석철학은 과학주의 를 넘어선 길을 열었다. 그것은 독일 관념론이 경험론 을 우회하는 길을 열었던 것과 유사하다.

인생의 마지막 15년간 로티는 ' 문화정치로서의 철학 (철학논문 IV)'과 ' 우리 나라를 달성한다 '(1998년) 등 저작의 출판을 계속했다. 후자는 듀이와 월트 휘트먼 의 독해에 부분적으로 근거한 정치적 선언으로 비판적 좌파와 대륙학파가 주장하는 패배주의적이고 반리버럴한 반 인간 주의 적 입장에 대해 진보적이고 플러그매틱한 좌파의 이념을 옹호했다. 로티는 이 반인간주의적 입장이 니체, 하이데거, 푸코와 같은 인물에 의해 구현되고 있다고 느꼈다. 그러한 이론가들은 '도착한 플라톤주의'에도 빠졌고, 거기에서 포괄적이고 형이상학적인 '숭고한' 철학을 만들어내려고 했다.

에두아르도 멘디에타에 따르면 "로티는 자신을 '포스트 모던의 부르주아 리버럴'이라고 칭했지만, 학술적 좌파를 비판하기도 했다. 그러나 그것은 진리에 반대한다. 는 아니고, 비애국적이기 때문이었다. 진리에 대한 로티의 선적 태도는 정치적 상대주의의 한 형태- 마카벨리 적인 정치의 타입-과 쉽게 혼동될 수 있는 것이었다” [ 18 ] .

스탠포드 대학으로 이적한 후 로티의 마지막 저작은 현대 생활에서의 종교의 자리매김, 리버럴 커뮤니티, 비교문학, '문화정치'로서의 철학에 관한 것이었다.

죽음 직전에 그는 '생명의 불'이라는 제목의 작품을 썼다(2007년 11월호의 ' 포에트리 '지에 게재) [ 19 ] . 그래서 그는 자신의 진단과 시의 위로에 대해 명상하고 다음과 같이 결론 지었다.

현재 나는 삶에서 조금 더 많은 시간을 시와 함께 보내고 싶었다. 이것은 산문에서는 표현할 수 없는 진리를 놓친 것을 두려워하기 때문이 아니다. 그런 진리는 존재하지 않았고, 죽음에 대해 스윈번과 랜더가 알고 있어 에피크로스와 하이데거가 이해할 수 없었던 것은 아무것도 없다. 오히려, 더 많은 친밀한 친구를 만들고 있으면 좋았던 것처럼, 보다 많은 옛부터의 명구를 암창할 수 있었다면, 보다 충실한 인생을 보낼 수 있었을 것이다. 더 풍부한 어휘를 가진 문화는 더 가난한 어휘 문화보다 더 완전하게 인간적이며 짐승에서 멀리 떨어져 있습니다. 개별 남녀도 그 기억이 시구로 풍부하게 채워질 때 더욱 완전하게 인간적이 된다.

2007년 6월 8일, 로티는 췌장암 에 의해 집에서 사망했다 [ 14 ] [ 16 ] [ 20 ] .

주요 작품

『철학과 자연의 거울』

'철학과 자연의 거울'(1979년)에서 로티는 현대 인식론 의 중심적 문제가 마음이 진심과 독립적인 외부적 현실을 충실하게 표상(또는 '경영')하려는 시도로서 마음의 도식에 의존하고 있다고 논한다. 이 은유를 포기하면 기초주의적 인식론의 전체 계획이 단순히 용해된다.

인식론적 기초주의자는 모든 신념이 다른 신념에 의해 정당화된다는 주장에 내재된 무한한 후퇴를 피하기 위해 일부 신념은 자기정당화적이어야 하고 모든 지식의 기초를 형성해야 한다고 생각한다. 그러나 로티는 (언어 내에서) 자명한 전제에 기초한 논의가 가능하다는 생각과 (언어 외) 비추론적인 감각에 기초한 논의가 가능하다는 생각을 비판했다.

첫 번째 비판은 분석적 으로 참 이라고 생각되는 문장, 즉 사실과는 독립적으로, 그 의미만으로 참이라고 생각되는 문장에 관한 쿠와인의 연구에 근거하고 있다 [ 21 ] . 콰인은 분석적으로 참인 문장의 문제는 '미혼 남성은 결혼하지 않았다'와 같은 동일성에 근거하지만 공허한 분석적 진리를 '독신자는 결혼하지 않는다'와 같은 동의성에 근거한 분석적 진리로 '변환'하려는 시도에 있다고 논한다 [ 22 ] . 그렇게 하려고 할 때에는 먼저 '미혼의 남성'과 '독신자'가 정확히 같은 것을 의미한다는 것을 증명해야 하지만, 사실을 고려하지 않고는 즉 종합적 진리 의 영역을 보는 것 없이는 불가능하다. 그러면 두 개념은 실제로 다르다는 것을 알 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, "bachelor"는 때때로 "학사"를 의미합니다 [ 23 ] . 따라서 콰인은 "분석적 문장과 종합적 문장 사이의 경계는 단순히 당겨지지 않는다"고 논하고, 이 경계 또는 구별은 "[...]경험론자의 비경험적인 교리, 형이상학적 신앙개조이다"라고 결론짓는다 [ 24 ] .

두 번째 비판은 감각 지각에서 비언어적이지만 인식 론적으로 관련된 '소여'가 이용 가능하다는 경험론의 생각에 대한 셀러스의 연구에 기초한다. 셀러스는 언어만이 논의의 기초로서 기능할 수 있다고 논한다. 비언어적인 감각 지각은 언어와 양립하지 않으므로 무관하다. 셀러스의 견해에서, 감각 지각에 인식론적으로 관련이 있는 「주어」가 존재한다고 하는 주장은 신화이다. 사실은 우리에게 “주어지는” 것이 아니라 언어 사용자인 우리가 적극적으로 “취하는” 것이다. 우리가 언어를 배운 후에 만, 우리는 관찰 할 수있게 된 개별 및 그 배열을 "경험적 데이터"로 해석 할 수 있습니다 [ 25 ] .

각각의 비판은 단독으로는 철학이 어떻게 진행되어야 하는가 하는 구상에 문제를 제기하지만, 전통의 충분한 부분을 이전의 포부와 함께 진행하기 위해 남겨두고 있다. 로티는 두 가지 비판을 결합하면 치명적이라고 주장했다. 우리의 논쟁의 자명한 기초로서 기능할 수 있는 특권적인 진리나 의미의 영역이 없기 때문에, 대신 우리는 그 길을 여는 신념으로 정의된 진리, 즉 어떤 형태로 우리에게 유용한 신념밖에 없다. 탐구의 실제 과정에 대한 유일한 가치의 설명은 로티에 따르면, 정상 기와 이상기간, 일상적인 문제 해결과 지적 위기 사이를 진동하는 분야의 진보의 표준 단계에 대한 쿤적 설명이었다.

기초주의를 부정한 후, 로티는 철학자에게 남겨진 몇 가지 역할 중 하나는 이전 실천과의 혁명적인 단절을 일으키려는 지적인 압(虻)으로 행동하는 것이며, 로티 자신이 기꺼이 맡은 역할이라고 논한다. 로티는 각 세대가 모든 분야를 그 시대에서 가장 성공적인 분야의 모델을 따르려고 한다고 제안한다. 로티의 관점에서 현대 과학의 성공으로 인해 철학과 인문 과학 학자들은 실수로 과학적 방법을 모방하게되었습니다.

“우연성·아이로니·연대”

'우연성·아이로니·연대'(1989년)에서 로티는 도널드 데이비드슨이 ( 알프레 토 타르스키 의 연구에 근거하여) 발전시킨 비인식론적인 의미론적 이론을 제외하고 가치 있는 진리의 이론은 존재하지 않는다고 논한다 [ 26 ] . 로티는 또한 철학자에게는 두 종류가 있다고 제안한다. 「사적」인 것 또는 「공적」인 것에 종사하는 철학자이다. (니체로부터 적응한 견해로 [ 27 ] , 로티는 마르셀프루스트 나 블라디미르 나보코프 의 소설에도 찾아낸다) 자기를(재)창조하는 보다 큰 능력을 주는 사적 철학자에게는, 공적인 문제의 해결은 기대되어서는 안 된다. 공공 철학 을 위해서는 대신 롤스 나 하버머스 와 같은 철학자에게 눈을 돌릴 수 있다 [ 28 ] . 그러나 로티에 따르면 후자는 "아이로니스트가되고 싶지 않은 리버럴"이다 [ 29 ] . 하버머스는 자신의 ' 커뮤니케이션적 이성의 이론 '이 합리주의의 갱신을 구성한다고 믿고 있지만, 로티는 후자와 모든 '보편적인' 주장은 완전히 포기되어야 한다고 생각한다 [ 30 ] .

이 저작은 또한 그의 철학과 일관된 정치적 비전을 구체적으로 표현하는 최초의 시도이기도 하며, 잔학성에 대한 반대로 묶인 다양한 커뮤니티의 비전이며, '정의'나 '공통의 인간성'과 같은 추상적인 관념으로 묶인 것은 아니다. 반기초주의와 일관되게 로티는 “잔학성이 무섭다는 신념에는 순환적이지 않은 이론적 뒷받침은 존재하지 않는다”고 말한다 [ 31 ] .

로티는 또한 자신의 심적 상태와 철학을 표현하는 데 사용되는 아이러니즘 이라는 용어를 도입합니다. 로티는 아이로니스트를 "언어를 줘서 그녀를 인간으로 한 사회화의 과정이 잘못된 언어를 주어 버려, 그 때문에 잘못된 종류의 인간으로 해 버린 것이 아닐까 걱정하는 사람"이라고 묘사한다. "그러나 그녀는 실수 기준을 나타낼 수 없다" [ 32 ] .

『객관성・상대주의・진리』

로티는 이 에세이집의 프로젝트를, 「자연과학과 문화의 나머지 부분과의 관계에 대한 반표상주의적 설명을 제공하려고 한다」 시도로서 묘사한다 [ 33 ] . '객관성·상대주의·진리: 철학논문집 제1권'(1990년)에 담긴 에세이 중에는 '철학에 대한 민주주의의 우선성'이 있으며, 거기서 로티는 공동체주의 비판자들에게 롤스를 옹호한다. 로티는 리버럴리즘은 "철학적 전제 없이 할 수 있다"고 논하는 한편, 공동체주의자들에게 "공동체를 자기의 구성요소로 하는 자기 개념은 리버럴 데모클래시와 잘 적합하다"고 양보한다 [ 34 ] . 게다가 로티에게 롤스는 하버머스 와 비교할 수 있으며, E.멘디에타의 말을 빌리면 미국판의 하버머스, 즉 사용만으로 생각한 계몽 의 인물이며, 이들은 같은 것의 두가지 다른 이름―공중이 집단적으로 어떻게 사는지를 결정하고, 무엇이 공공선의 목표인지를 결정하기 위해 이성을 사용하는 것―이다」라고 한다 [ 18 ] . 로티에 있어서 사회제도는 "보편적이고 비역사적인 질서를 구현화하려는 시도보다는 협력의 실험으로 생각되어야 한다" [ 35 ] .

"하이데거와 다른 사람들에 대한 논문"

이 문장에서 로티는 주로 대륙의 철학자 마르틴 하이데거 와 잭 데리다 에 초점을 맞춘다. 그는 이러한 유럽의 '포스트 니체주의자들'이 형이상학을 비판하고 진리의 대응설을 거절한다는 점에서 미국의 플러그 마티스트들과 많은 것을 공유하고 있다고 논한다 [ 36 ] . 이전의 저작으로 논의한 것을 다루고 발전시키고 [ 37 ] , 로티는 데리다는 철학적(또는 문학적) "방법"의 발명자로서가 아니라 서양철학의 전통을 우회하려고 하는 재미있는 작가로서 볼 때 가장 유용하다고 주장한다. 이 맥락에서 로티는 폴 드 맨과 같은 데리다 의 추종자들이 탈구축적 문학 이론을 너무 심각하게 받아들이고 있다고 비판한다.

『미국 미완의 프로젝트』

『미국 미완의 프로젝트――20세기 미국에 있어서의 좌익사상』(1998년)에서, 로티는, 좌파의 2개의 측면으로서 간주하는 것을 구별한다. 문화적 좌파와 진보적 좌파이다. 그는 푸코와 같은 포스트구조주의자나 리오탈과 같은 포스트모더니스트에게 예시되는 문화적 좌파를 사회의 비판은 제공하지만 대안을 제공하지 않는다(혹은 막연하고 너무 포기하고 같은 대안만을 제공한다)고 비판한다. 이 지식인들은 사회의 병에 대한 통찰력을 갖고 있다고 주장하지만, 로티는 그들이 대안을 제공하지 못하고 때로는 진보의 가능성을 부인한다고 시사한다. 한편, 로티에게 플러그 마티스트 의 존 듀이 , 휘트먼 , 제임스 볼드윈 으로 예시되는 진보적 좌파는 더 나은 미래에 대한 희망을 우선한다. 로티는 희망 없이는 변화가 정신적으로 생각되지 않고 문화적 좌파가 냉소주의를 창출하기 시작했다고 논한다. 로티는 진보적 좌파를 플러그 마티즘의 철학적 정신에서 행동하고 있다고 본다.

인권에 대하여

로티의 인권의 개념은 감정 의 개념에 기초를 두고 있다 . 그는 역사를 통해 인간이 특정 집단을 비인간적 또는 아인간적으로 간주하는 다양한 수단을 고안해 왔다고 주장했다. 합리주의적(기초적 주의적) 용어로 생각하는 것은 이 문제를 해결하지 않는다고 그는 주장했다. 로티는 감정교육을 통해 인권침해의 발생을 막기 위해 글로벌 인권문화 창조를 제창했다. 그는 다른 사람의 고통을 이해하기 위해 공감 의 감각을 창조하거나 다른 사람에게 공감을 가르쳐야한다고 논했다 [ 38 ] .

희망에 대해

로티는 철학자 닉 골이 '무한한 희망' 또는 일종의 '우울한 개량주의 '로 특징짓는 것을 제창한다. 이 견해에 따르면 로티는 확실성에 대한 기초주의적 희망을 지속적인 성장과 끊임없는 변화에 대한 희망으로 대체한다. 그는 이것으로 현재는 상상할 수 없는 새로운 방향으로 대화와 희망을 향하게 할 수 있다고 믿고 있다 [ 39 ] .

로티는 1982년 저서 '플러그마티즘의 귀결' [ 40 ] 에서 이 무한한 희망을 명확하게 표현하고, 거기서 도매적 희망 대 소매적 희망이라는 틀을 적용한다. 여기서 그는 다음과 같이 말한다 : "플러그마티즘의 세 번째, 그리고 마지막 특성화를 제공함으로써 요약하겠습니다. 말하는 교설이다-대상의 성질이나, 마음의 성질이나, 언어의 성질로부터 도출되는 도매적 제약은 존재하지 않고, 단지 우리 동료의 탐구자들의 발언에 의해 제공되는 소매적 제약만이 존재한다.”

수용과 비판

로티는 가장 널리 논의되고 논쟁을 부르는 현대 철학자 중 하나이며 [ 15 ] 그의 저서는 분야의 다른 많은 존경받는 인물들로부터 사려 깊은 반응을 이끌어내고 있다. 예를 들어 로버트 브랜덤 의 선집 '로티와 그 비판자들'에서 로티의 철학은 도널드 데이비드슨 , 유르겐 하버머스 , 힐러리 패트남 , 존 맥다웰 , 잭 부브레스 , 다니엘 데넷 등에 의해 논의되고 있다 [ 41 ] . 2007년 로저 스크루톤 은 다음 과 같이 썼다 . 랄프 마빈 투마오브는 로티 가 장-프랑소와 리오타르 의 메타나라티브 의 영향을 받고 있으며, “포스트 모더니즘은 로티의 저작에 의해 더욱 영향을 받았다”고 덧붙였다 [ 43 ] .

맥다웰은 특히 '철학과 자연의 거울'(1979년)로부터 로티의 강한 영향을 받고 있다 [ 44 ] . 대륙 철학에서는 유르겐 하버머스, 장니 바티모, 잭 데리다 , 브레 흐트 베르마 , 한스 요아스 , 샹탈 무프 , 사이먼 클리치리 , 먹이 사리넨 , 마이크 샌드보테 등이 다양한 형태로 로티의 사상의 영향을 받고 있다. 미국 소설가 데이비드 포스터 월리스 는 단편집 『망각: 이야기집 』 속 단편에 '철학과 자연의 거울'이라는 타이틀을 붙여 비평가들은 월레스의 아이러니에 관한 저작의 일부에 로티의 영향을 발견하고 있다 [ 45 ] .

수잔 하크 는 로티의 네오플러그마티즘의 격렬한 비판자이다. 하크는 로티가 플러그 마티스트라는 주장 자체를 비판하고 '우리 플러그 마티스트들'이라는 짧은 극을 썼다. 거기에서는 로티와 찰스 샌더스 퍼스가 자신의 저작으로부터의 정확한 인용만을 사용하여 가상의 대화를 한다. 하크에게 로티의 네오플러그마티즘과 퍼스의 플러그마티즘을 연결하는 것은 이름뿐이다. 하크는 로티의 네오플러그마티즘은 반철학적이고 반지성적이며, 사람들을 더욱 수사적 조작에 노출시키는 것으로 생각하고 있다 [ 15 ] [ 46 ] [ 47 ] .

로티는 공언된 리버럴이었지만 그의 정치철학과 도덕철학은 좌파의 논자들로부터 공격을 받고 있으며, 그 일부 사람들은 그들이 사회 정의를 위한 불충분한 틀이라고 생각하고 있다 [ 48 ] . 로티는 또한 과학이 세계를 묘사할 수 있다는 생각을 거절한 것으로도 비판되었다 [ 49 ] . '우연성·아이로니·연대'에 대한 하나의 비판은 로티의 철학적 영웅인 아이러니스트 ( 엘리트주의적인 인물이라는 것이다 [ 50 ] . 로티는 대부분의 사람들은 '상식적으로 유명론자이자 역사주의자'이지만 아이러니스트가 아니라고 논한다. 그들은 초월적인 것에 대한 개별적인 것에 대한 지속적인 주의( 유명론 )와 다른 개인과 나란히 우연한 살아있는 경험의 연속에서의 자신의 위치에 대한 인식( 역사주의 )을 결합하지만, 아이로니스트처럼 결과적인 세계관에 대한 지속적인 의심을 가질 필요는 없다. 아이로니스트란, 「자신의 종국의 어휘에 대해 근본적이고 계속적인 의혹을 가진다」, 즉 「인간이 자신들의 행동, 신념, 생활을 정당화하기 위해서 사용하는 일련의 말」에 대해 의혹을 가지고, "그들의 어휘로 표현된 논의가 이러한 의혹을 뒷받침하거나 해소할 수 없다는 것을 인식"하고, "자신의 어휘가 다른 어휘보다 현실에 가깝다고는 생각하지 않는다"인물이다 [ 51 ] . 한편 이탈리아 철학자 쟈니 바티모와 스페인 철학자 산티아고 사바라 는 2011년 저서 ' 해석학적 공산주의: 하이데거에서 마르크스로 ``리처드 로티와 함께 우리도 ``현대의 학술적 마르크스주의자들이 마르크스와 엥겔스로부터 계승하고 있는 주요한 것은, 협동적 공동체의 탐구는 과학적이어야 하고, 유토피아적이어서는 안 되고, 인식적이어야 한다고 확실해야 한다. 우리가 보여주는 것처럼 해석학은 과학의 지식과는 대조적으로 현대의 보편성이 아닌 포스트 모던의 개별주의를 주장하기 때문에 로티가 언급하는 모든 유토피아적이고 로망주의적인 특징을 포함 한다 [ 52 ]

로티는 자신의 견해를 뒷받침하기 위해 종종 광범위한 다른 철학자들을 인용하지만, 그들의 저작에 대한 그의 해석은 분쟁되었다 [ 15 ] . 그는 재해석의 전통에서 연구하고 있기 때문에 다른 사상가들을 '정확하게' 묘사하는 것에 관심이 없고 오히려 문학 비평가들이 소설을 사용하는 것처럼 사용하고 있다. 그의 에세이 "철학의 역사 기술법 : 네 장르"는 그가 철학 역사상 위대한 사상가들을 어떻게 다루는지에 대한 철저한 설명이다. '우연성·아이로니·연대'에서 로티는 자신의 저작을 비판하는 사람들을 그들의 철학적 비판이 로티 자신의 철학 속에서 명시적으로 거절된 공리를 이용하여 행해지고 있다고 논함으로써 무장 해제하려고 한다 [ 53 ] . 예를 들어, 그는 비합리성의 주장을 일상적인 '타인성'의 긍정으로 정의하고, 따라서 로티 는 논한다 .

수상 경력과 영예

- 1973년: 구겐하임 휄로우 십 [ 55 ]

- 1981년: 맥아더 휄로우십 [ 16 ]

- 1983년: 미국 예술 과학 아카데미 회원으로 선출 [ 56 ]

- 2005년: 미국 철학 협회 회원으로 선출 [ 57 ]

- 2007년: 토마스 제퍼슨 메달 , 미국 철학 협회에서 수여 [ 58 ]

책

- 단저·공저

- 철학과 자연의 거울 . 프린스턴: 프린스턴 대학교 출판부, 1979년.

- 야가 케이이치 감역, 『철학과 자연의 거울』, 산업 도서 , 1993년.

- 실용주의의 결과 . 미니애폴리스: 미네소타 대학교 출판부, 1982. ISBN 978-0816610631

- 무로이 나오 · 요시오카 요 · 카토 테츠히로 · 하마 히데오 · 청 무역, "철학의 탈 구축 - 플러그 마티즘의 귀결", 오차 의 물 서 방판 , 1985 년.

- 문고판『플러그마티즘의 귀결』, 쓰 쿠마 서방, 2014년.

- 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. ISBN 978-0521353816

- 철학 논문 1-4권:

- 객관성, 상대주의, 그리고 진리: 철학 논문 I. 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1991. ISBN 978-0521353694

- 하이데거와 다른 이들에 대한 에세이: 철학 논문 II . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1991.

- 진실과 진보: 철학 논문 III . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1998.

- 문화 정치로서의 철학: 철학 논문 IV . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 2007.

- 토미타 쿄히코·도다 고분 역 , 「문화 정치로서의 철학」, 이와나미 서점, 2011년.

- 정신, 언어, 그리고 형이상학: 초기 철학 논문들 (편집자: S. 리치, J. 타르탈리아). 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 2014. ISBN 978-1107612297 .

- 『 우리 나라를 이루다 : 20세기 미국의 좌파 사상』 . 매사추세츠주 케임브리지: 하버드 대학교 출판부, 1998. ISBN 978-0674003118

- 오자와 테루히코역 , 「미국 미완의 프로젝트――20 세기 미국에 있어서의 좌익 사상」, 도요 서방, 2000년.

- 철학과 사회적 희망 . 뉴욕: 펭귄, 2000.

- 스도 훈임 와타나베 케이 진역 , '리버럴 유토피아라는 희망', 이와나미 서점 , 2002년.

- 상사에 맞서, 과두정치에 맞서: 리처드 로티와의 대화 . 시카고: 프리클리 패러다임 프레스, 2002.

- Gianni Vattimo Ed 와 함께하는 종교의 미래 . 제임스 자발라. 뉴욕: 컬럼비아 대학 출판부, 2005. ISBN 978-0231134941

- 오늘날의 윤리: 철학과 종교의 공통점 찾기 . 뉴욕: 컬럼비아 대학교 출판부, 2005. ISBN 978-0231150569

- 파스칼 엥겔 과 함께하는 진실의 용도 , 윌리엄 맥콰이그 번역, 뉴욕: 컬럼비아 대학교 출판부, 2007. ISBN 9780231140140

- 우리는 무엇을 바랄 수 있을까?: 정치 에세이 , C. 보파릴, WP 말레츠키 편. 프린스턴: 프린스턴 대학교 출판부, 2022. ISBN 9780691217529

- 편저서

- 언어학적 전환, 철학적 방법에 관한 에세이 , (1967), Richard M. Rorty 편집, 시카고 대학교 출판부, 1992, ISBN 978-0226725697 (서론 및 두 개의 회고적 에세이)

- 역사 속의 철학(Philosophy in History ). R. Rorty, JB Schneewind , Quentin Skinner 편집 , 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1985(R. Rorty의 에세이, "철학사", 29-76쪽)

- 일본 오리지널 번역 논문집

- 토미타 쿄히코 역, 「연대와 자유의 철학――2원론의 환상을 넘어」, 이와나미 서점 , 1988년.

- 토미타 쿄히코역, 『로티 논집――「보라의 말들」/지금 묻는 미국의 지성』, 2018년.

각주

- ^ 로버트 브랜덤은 로티의 반표상주의를 다음과 같이 요약합니다. "간단히 말해서, 로티의 의미론적 표상주의 비판은 다음과 같습니다. 규범적 관계는 오로지 어휘 내적인 것입니다. 어휘 외적인 관계는 오로지 인과적인 것입니다. 표상은 옳고 그름을 평가하는 규범적 관계이자, 어휘 내의 표상과 그 어휘 외부의 표상 사이의 관계라고 주장합니다. 따라서 어휘와 그 환경의 관계에 대한 표상적 모델은 거부되어야 합니다." 로버트 브랜덤(2000년 10월 11일). 실용주의의 어휘: 자연주의와 역사주의의 종합. (로티와 그의 비평가들) . 매사추세츠주 몰든. 160쪽. ISBN 0-631-20981-6 . OCLC 43109795

- ^ 로티는 지식-그것(knowledge-that)과 지식-어떻게(knowledge-how)를 구분했습니다. 언어 사용자만이 지식-그것(knowledge-that)(인식적으로 타당한 지식)을 가질 수 있는 반면, 박테리아와 바이러스를 포함한 모든 생명체는 "지식-어떻게"(knowledge-how)를 가질 수 있습니다. 로티, 리처드(Richard Rorty, 2000년 10월 11일). 배리 앨런에게 보낸 답신. (Rorty and His Critics에서 발췌) . 매사추세츠주 몰든. 238-239쪽. ISBN 0-631-20981-6 . OCLC 43109795

- ^ Rorty, Richard (1982). 실용주의의 결과: 에세이, 1972-1980 . 미니애폴리스. 158쪽. ISBN 0-8166-1064-9 . OCLC 8222790

- ^ Rorty, Richard (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity . Cambridge. pp. 6, 21. ISBN 0-521-35381-5 . OCLC 18290785. "세상은 일단 우리가 언어로 프로그래밍되면 우리로 하여금 어떤 신념을 갖게 할 수 있습니다. 하지만 세상은 우리가 말할 언어를 제안할 수는 없습니다. 오직 다른 인간만이 그렇게 할 수 있습니다. [...] 진실은 문장의 속성이고, 문장은 어휘에 의존하여 존재하며, 어휘는 인간에 의해 만들어지므로 진실 또한 마찬가지입니다."

- ^ "아이러니스트는 자신이 잘못된 부족에 입문당했거나 잘못된 언어 게임을 배우게 되었을 가능성을 걱정하며 시간을 보낸다 . 그녀는 언어를 부여함으로써 자신을 인간으로 만들어준 사회화 과정이 잘못된 언어를 부여했고, 결국 잘못된 인간으로 만들어버렸을지도 모른다고 걱정한다. 하지만 그녀는 그 잘못됨의 기준을 제시할 수 없다. 따라서 그녀가 자신의 상황을 철학적 용어로 표현하려고 할수록, 세계관(Weltanschauung) , '관점', 변증법, ' 영어판 , '역사적 시대', 언어 게임 , ' 재기술', '어휘', '아이러니'와 같은 용어를 끊임없이 사용하며 자신이 뿌리가 없다는 사실을 더욱 상기시킨다." Rorty, Richard (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity . Cambridge. p. 75. ISBN 0-521-35381-5 . OCLC 18290785

- ^ Rorty, Richard (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity . Cambridge. p. 189. ISBN 0-521-35381-5 . OCLC 18290785

- ^ “ 리처드 로티: 미국 철학자의 탄생 ”. press.uchicago.edu (1931년 10월 4일). 2012년 9월 26일 접속.

- ↑ Bernstein, Adam (2007년 6월 11일). “Richard Rorty, 75; Leading US Pragmatist Philosopher” . washingtonpost.com 2012년 9월 26일에 확인함.

- ^ a b c 브루스 쿠클리크. "닐 그로스, 리처드 로티: 미국 철학자의 탄생." 찰스 S. 피어스 학회지 47.1(2011):36.

- , "Private Life and Public Commitment: From Walter Rauschenbusch to Richard Rorty," in Pragmatist's Progress?: Richard Rorty and American Intellectual History , ed. John Pettegrew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2500 9780847690626

- ↑ a b c “ Jürgen Habermas: Philosopher, poet and friend (12/06/2007) ”. signandsight. 2012년 9월 26일에 확인함.

- ^ 마르케티, 잔카를로. "리처드 로티와의 인터뷰." Philosophy Now 43권, 2003년 10월-11월.

- ↑ Ryerson, James. "The Quest for Uncertainty: Richard Rorty's Pragmatic Pilgrimage" 링가 프랑카 Vol. 10, No. 9. December 2000/January 2001.

- ^ a b "저명한 대중 지식인이자 논쟁적인 철학자인 리처드 로티가 75세의 나이로 사망했습니다" (스탠포드 대학 발표), 2007년 6월 10일

- ^ a b c d e Ramberg, Bjørn (2009년 8월 1일). "Richard Rorty" . Zalta, Edward N.. 스탠퍼드 철학 백과사전 . 스탠퍼드 대학교 형이상학 연구소

- ^ a b c d "철학자 리처드 로티, 75세로 사망" (뉴욕 타임스 부고), 2007년 6월 11일

- ^ 라이어슨, 제임스. "에세이: 쾌활하게 생각하기." 뉴욕 타임스 북 리뷰 . 2007년 7월 22일: 27쪽.

- ↑ a b Mendieta, Eduardo (2017년 7월 22일). “ Rorty and Post-Post Truth ”. lareviewofbooks . 2023년 4월 13일에 확인함.

- ^ 로티, 리처드 (2007년 11월). "삶의 불꽃" . Poetry Magazine .

- ^ "리처드 로티," (짧은 부고), 2007년 6월 9일.

- ^ Quine, WV (1961). 『논리적 관점에서: 아홉 편의 논리철학 에세이』, 2차 개정판 . Harper torchbooks. 하버드 대학교 출판부. 21쪽. ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3 , 2021년 4월 2일 출판.

- ^ Quine, WV (1961). 『논리적 관점에서: 아홉 편의 논리철학 에세이』, 2차 개정판 . Harper torchbooks. 하버드 대학교 출판부. 100-1, 21-22쪽. ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3, 2021년 4월 2일 출판.

- ^ Quine, WV (1961). 『논리적 관점에서: 아홉 편의 논리철학 에세이』, 2차 개정판 . Harper torchbooks. 하버드 대학교 출판부. 28쪽. ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3 , 2021년 4월 2일 출판.

- ^ Quine, WV (1961). 『논리적 관점에서: 아홉 편의 논리철학 에세이, 2차 개정판』 . Harper torchbooks. 하버드 대학교 출판부. 37쪽. ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3. 2021년 4월 2일 출판.

- ↑ Sellars, W.; Brandom, WSR; Rorty , PCLR; Rorty, R.; Brandom, R. (1997). Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind . Minnesota studies in the philosophy of science. Harvard University Press. pp . 2021년 4월 2일에 확인함.

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 11-22쪽. ISBN 978-0521353816

- ↑ 로티는 니체가 객관적 진리의 개념을 완전히 포기할 것을 제안한 최초의 철학자라고 논한다. 니체에게 인간은 순수한 동물성 상태에서 단순히 상승하려고 하는 것이 아니라 '자기 창조'했다는 인식에 의해 위안을 끌어내야 한다. Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. pp. 23-43. ISBN 978-0521353816

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 56-70쪽. ISBN 978-0521353816

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 61쪽. ISBN 978-0521353816

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 68쪽. ISBN 978-0521353816

- ↑ Rorty, R.; Rorty, PCLR; Cambridge University Press; Richard, R. (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity . Clark lectures. Cambridge University Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-521-36781-3 2021년 4월.

- ↑ Rorty, R.; Rorty, PCLR; Cambridge University Press; Richard, R. (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity . Clark lectures. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-521-36781-3 2021년

- ^ 객관성, 상대주의 및 진실: 철학 논문, 제1권 (1990), p. I

- ^ 객관성, 상대주의 및 진리: 철학 논문, 제1권 (1990), 179쪽

- ^ 객관성, 상대주의 및 진리: 철학 논문, 제1권 (1990), 196쪽

- ^ 하이데거와 다른 이들에 대한 에세이: 철학 논문 II . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1991.

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 122-135쪽. ISBN 978-0521353816

- ^ Barreto, José-Manuel 참조. "Rorty와 인권: 우연성, 감정, 그리고 이야기를 통해 인권을 옹호하는 방법." Utrecht Law Review, 제7권 2호, 2011년 4월

- ^ Gall, Nick. "Dewey와 Rorty: 실용주의적 희망을 새로운 방향으로 보내기." 2022년 11월, Erraticus [1] .

- ^ 로티, 리처드 (1982). 희망의 결과. 미네소타 대학교 출판부.

- ^ 브랜덤, 로버트 B. (2000년 10월 3일). 로티와 그의 비평가들 . 와일리. ISBN 0631209824

- ↑ Scruton, Roger (2007년 6월 12일). “ Richard Rorty's legacy ”. openDemocracy. 2012년 9월 26일에 확인함.

- ^ “ 로티의 철학과 자연의 거울(pdf) ” (2016년 10월 18일). 2025년 2월 13일 접속.

- ^ 맥도웰은 《마음과 세계》 (9~10쪽) 서문에서 "로티의 작업이 내가 여기서 입장을 정의하는 방식의 중심이라는 것은 분명할 것이다"라고 썼다.

- ↑ Howard, Jennifer. “The Afterlife of David Foster Wallace” . Chronicle of Higher Education 2013년 12월 30일에 확인함.

- ^ Susan Haack (1997년 11월). “ Vulgar Rortyism ”. New Criterion . 2025년 2월 13일 접속.

- ^ Haack, Susan (1993). “9장: 저속한 실용주의: 비교육적인 전망”. Evidence and Inquiry . Oxford UK: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631118510 . OL 1398949M

- ^ "객관성과 행동: 월마트와 마르크스와 니체의 유산" , 월마트와 같은 기업에 맞서 싸우는 데 있어 로티의 철학이 부족하다는 테리 이글턴 의 공격에 대한 논의

- ^ "과학이 현실을 묘사하는 특별한 힘을 인식하지 못하는 것은 '과학적 진실 추구의 입증된 방법과 그 힘에 대한 무지함'을 보여준다고 다니엘 데닛은 썼습니다." [2]

- ^ “ Rob Reich – The Paradoxes of Education in Rorty's Liberal Utopia ”. 2006년 6월 15일 시점의 오리지널보다 아카이브 . 2025년 2월 13일에 확인함.

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 73쪽, ISBN 978-0521353816

- ^ 지아니 바티모 , 산티아고 자발라. 『공산주의 : 하이데거에서 마르크스까지 』 컬럼비아대학교 출판부. 2011.

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 44쪽, ISBN 978-0521353816

- ^ 우연성, 아이러니, 그리고 연대 . 케임브리지: 케임브리지 대학교 출판부, 1989. 48쪽, ISBN 978-0521353816

- ↑ “ Richard M. Rorty ”. www.gf.org . John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. 2020년 9월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ “ Richard McKay Rorty ”. www.amacad.org . American Academy of Arts & Sciences. 2020년 9월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ “ APS Member History ”. search.amphilsoc.org . 2021년 6월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ “ 2007 Thomas Jefferson Medal ”. American Philosophical Society. 2020년 9월 2일에 확인함.

참고문헌

- David Rondel, ed., Rorty의 Cambridge Companion, 2021

- Randall Auxier , Eli Kramer, Krzysztof Piotr Skowroski, 편집, Rorty and Beyond

- 울프 슐렌버그, 낭만주의와 실용주의: 리처드 로티와 시화된 문화의 개념 , 2015

- 크르지스토프 피오트르 스코브론스키, 리처드 로티의 신실용주의에서의 가치, 평가, 그리고 가치론적 규범 , 2015

- Janack , What We Mean By 2012

- Janack , editor,of Richard Rorty , 2010

- James Tartaglia , Richard Rorty: Critical Assessments .,

- Gross , Richard Rorty: The Making of an American 2008

- 그로스, 닐. 2019. 리처드 로티: 미국 철학자의 탄생. 시카고 대학교 출판부.

- 로티의 재기술의 정치학 / 기드온 칼더, 2007

- 로티와 자연의 거울 / 제임스 타르탈리아, 2007

- 리처드 로티: 실용주의와 정치적 자유주의 / 마이클 베이컨, 2007

- 리처드 로티: 정치와 비전 / 크리스토퍼 보파릴, 2006

- 리처드 로티: 그의 철학에 대한 논의 / 안드레아스 비스, 2005

- 리처드 로티 / 찰스 B 기뇽, 2003

- 로티 / 기드온 칼더, 2003

- 리처드 로티의 미국 신앙 / 타웁, 가드 슈무엘, 2003

- 윤리적 아이러니: 키에르케고르, 로티, 그리고 교육적 탐구 / 로러, 파트리샤 진, 2003

- 개인화를 위한 방법으로서의 철학: 로티와 캐벨의 저서 읽기 / 곽덕주, 2003

- 리처드 로티 / 앨런 R 말라초프스키, 2002

- 리처드 로티: 비판적 대화 / 매튜 페스텐슈타인, 2001

- 리처드 로티: 교육, 철학, 그리고 정치 / 마이클 피터스, 2001

- 로티와 그의 비평가들 / 로버트 브랜덤, 2000

- 로티에 대하여 / 리차드 루마나, 2000

- 철학과 자유: 데리다, 로티, 하버마스, 푸코 / 존 맥컴버, 2000

- 실용주의자의 진보?: 리처드 로티와 미국 지성사 / 존 페테그루, 2000

- 현대적 자아의 문제: 로티, 테일러, 니체, 푸코에 대한 성찰 / 두드릭, 데이비드 프랜시스, 2000

- 마지막 개념 혁명: 리처드 로티의 정치 철학에 대한 비판 / 에릭 갠더, 1999

- 리처드 로티의 정치: 미국 세기말의 자유주의 / 마르카르 멜코니안, 1999

- 우정의 작업: 로티, 그의 비평가들, 그리고 연대의 프로젝트 / 다이앤 로스레더, 1999

- 완벽함에 대한 사랑을 위하여: 리처드 로티와 자유교육 / 르네 빈센트 아르실라, 1995

- 로티와 실용주의: 철학자가 비판자들에게 응답하다 / Herman J Saatkamp, 1995

- 리처드 로티: 새로운 실용주의의 예언자이자 시인 / 데이비드 L 홀, 1994

- 로티 읽기: 철학과 자연의 거울(그리고 그 너머)에 대한 비판적 반응 / 앨런 R. 말라코프스키, 1990

- 로티의 인본주의적 실용주의: 민주화된 철학 / 콘스탄틴 콜렌다, 1990

박영민 카이스트 부설 한국과학영재

박영민 카이스트 부설 한국과학영재