Thích Nhất Hạnh

Thích Nhất Hạnh | |

|---|---|

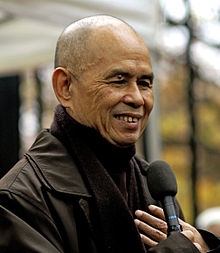

Thích Nhất Hạnh in Paris in 2006 | |

| Title | Thiền Sư (Zen master) |

| Other names | Thầy (teacher) |

| Personal | |

| Born | Nguyễn Xuân Bảo 11 October 1926 |

| Religion | Thiền Buddhism |

| School | Linji school (Lâm Tế)[1] Order of Interbeing Plum Village Tradition |

| Lineage | 42nd generation (Lâm Tế)[1] 8th generation (Liễu Quán)[1] |

| Other names | Thầy (teacher) |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Thích Chân Thật |

| Based in | Plum Village Monastery (currently in Từ Hiếu Temple near Huế, Vietnam) |

Thích Nhất Hạnh (/ˈtɪk ˈnjʌt ˈhʌn/; Vietnamese: [tʰǐk̟ ɲə̌t hâjŋ̟ˀ] ( listen); born as Nguyễn Xuân Bảo[2] on 11 October 1926[3]) is a Vietnamese Thiền Buddhist monk, peace activist, and founder of the Plum Village Tradition.

listen); born as Nguyễn Xuân Bảo[2] on 11 October 1926[3]) is a Vietnamese Thiền Buddhist monk, peace activist, and founder of the Plum Village Tradition.

Thích Nhất Hạnh spent most of his later life residing at the Plum Village Monastery in southwest France,[4] travelling internationally to give retreats and talks. He coined the term "Engaged Buddhism" in his book Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire.[5]

After a long exile, he was permitted to visit Vietnam in 2005.[6] In November 2018, he returned to Vietnam to spend his remaining days at his "root temple", Từ Hiếu Temple, near Huế.[7]

He is active in the peace movement, promoting nonviolent solutions to conflict.[10] He also refrains from consuming animal products, as a means of nonviolence toward animals.[11][12]

Biography[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

Nhất Hạnh was born as Nguyễn Xuân Bảo, in the city of Huế in Central Vietnam in 1926. At the age of 16 he entered the monastery at nearby Từ Hiếu Temple, where his primary teacher was Zen Master Thanh Quý Chân Thật.[13][14][15] A graduate of Báo Quốc Buddhist Academy in Central Vietnam, Thích Nhất Hạnh received training in Vietnamese traditions of Mahayana Buddhism, as well as Vietnamese Thiền, and received full ordination as a Bhikkhu in 1951.[16]

In the following years he founded Lá Bối Press, the Vạn Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon, and the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS), a neutral corps of Buddhist peaceworkers who went into rural areas to establish schools, build healthcare clinics, and help rebuild villages.[4]

On 1 May 1966, at Từ Hiếu Temple, he received the "lamp transmission" from Zen Master Chân Thật, making him a dharmacharya (teacher).[13] Nhất Hạnh is now the spiritual head of the Từ Hiếu Pagoda and associated monasteries.[13][17]

During the Vietnam War[edit]

In 1961 Nhất Hạnh went to the US to teach comparative religion at Princeton University,[18] and was subsequently appointed lecturer in Buddhism at Columbia University.[18] By then he had gained fluency in French, Chinese, Sanskrit, Pali, Japanese and English, in addition to his native Vietnamese. In 1963, he returned to Vietnam to aid his fellow monks in their nonviolent peace efforts.[18]

Nhất Hạnh taught Buddhist psychology and prajnaparamita literature at Vạn Hanh Buddhist University, a private institution that taught Buddhist studies, Vietnamese culture, and languages.[18]

At a meeting in April 1965, Vạn Hanh Union students issued a Call for Peace statement. It declared: "It is time for North and South Vietnam to find a way to stop the war and help all Vietnamese people live peacefully and with mutual respect." Nhất Hạnh left for the U.S. shortly afterwards, leaving Sister Chân Không in charge of the SYSS. Vạn Hạnh University was taken over by one of the chancellors, who wished to sever ties with Nhất Hạnh and the SYSS, accusing Chân Không of being a communist. Thereafter the SYSS struggled to raise funds and faced attacks on its members. It persisted in its relief efforts without taking sides in the conflict.[5]

Nhất Hạnh returned to the US in 1966 to lead a symposium in Vietnamese Buddhism at Cornell University and continue his work for peace. While in the US, he visited Gethsemani Abbey to speak with Thomas Merton.[19] When Vietnam threatened to block Nhất Hạnh's reentry to the country, Merton wrote an essay of solidarity, "Nhat Hanh is my Brother".[19][20] In 1965 he had written Martin Luther King, Jr. a letter titled "In Search of the Enemy of Man". During his 1966 stay in the US Nhất Hạnh met King and urged him to publicly denounce the Vietnam War.[21] In 1967, King gave the speech Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence at the Riverside Church in New York City, his first to publicly question U.S. involvement in Vietnam.[22] Later that year, King nominated Nhất Hạnh for the 1967 Nobel Peace Prize. In his nomination, King said, "I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of [this prize] than this gentle monk from Vietnam. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity".[23] That King had revealed the candidate he had chosen to nominate and had made a "strong request" to the prize committee was in sharp violation of Nobel traditions and protocol.[24][25] The committee did not make an award that year.

Nhất Hạnh moved to France and became the chair of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation.[18] When the Northern Vietnamese army took control of the south in 1975, he was denied permission to return to Vietnam.[18] In 1976–77 he led efforts to help rescue Vietnamese boat people in the Gulf of Siam,[26] eventually stopping under pressure from the governments of Thailand and Singapore.[27]

A CIA document from the Vietnam War has called Thích Nhất Hạnh a "brain truster" of Thích Trí Quang, the leader of a dissident group.[28]

Establishing the Order of Interbeing[edit]

Nhất Hạnh created the Order of Interbeing (Vietnamese: Tiếp Hiện) in 1966. He heads this monastic and lay group, teaching Five Mindfulness Trainings[29] and the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings.[30] In 1969 he established the Unified Buddhist Church (Église Bouddhique Unifiée) in France (not a part of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam). In 1975 he formed the Sweet Potato Meditation Centre. The centre grew and in 1982 he and Chân Không founded Plum Village Monastery, a vihara[A] in the Dordogne in the south of France.[4] The Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism[31] (formerly the Unified Buddhist Church) and its sister organization in France the Congregation Bouddhique Zen Village des Pruniers are the legally recognised governing bodies of Plum Village in France, Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush, New York, the Community of Mindful Living, Parallax Press, Deer Park Monastery in California, Magnolia Grove Monastery in Batesville, Mississippi, and the European Institute of Applied Buddhism in Waldbröl, Germany.[32][33] According to the Thích Nhất Hạnh Foundation, the charitable organization that serves as the Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism's fundraising arm, the monastic order Nhất Hạnh established comprises 589 monastics in 9 monasteries worldwide. [34]

Nhất Hạnh established two monasteries in Vietnam, at the original Từ Hiếu Temple near Huế and at Prajna Temple in the central highlands. He and the Order of Interbeing have established monasteries and Dharma centres in the United States at Deer Park Monastery (Tu Viện Lộc Uyển) in Escondido, California, Maple Forest Monastery (Tu Viện Rừng Phong) and Green Mountain Dharma Center (Ðạo Tràng Thanh Sơn) in Vermont and Magnolia Grove Monastery (Đạo Tràng Mộc Lan) in Mississippi, the second of which closed in 2007 and moved to the Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush, New York. These monasteries are open to the public during much of the year and provide ongoing retreats for laypeople. The Order of Interbeing also holds retreats for specific groups of laypeople, such as families, teenagers, military veterans, the entertainment industry, members of Congress, law enforcement officers and people of colour.[35][35][36][37][38] Nhất Hạnh conducted peace walks in Los Angeles in 2005 and 2007.[39]

Notable members of the order of interbeing and disciples of Nhất Hạnh include Skip Ewing, founder of the Nashville Mindfulness Center; Natalie Goldberg, author and teacher; Chân Không, dharma teacher; Caitriona Reed, dharma teacher and co-founder of Manzanita Village Retreat Center; Larry Rosenberg, dharma teacher; Cheri Maples, police officer and dharma teacher; and Pritam Singh, real estate developer and editor of several of Nhất Hạnh's books.

Other notable students of Nhất Hạnh include

- Joan Halifax, founder of the Upaya Institute; Albert Low, Zen teacher and author;

- Joanna Macy, environmentalist and author;

- Jon Kabat-Zinn, creator of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR);

- Jack Kornfield, dharma teacher and author;

- Christiana Figueres, former Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change;

- Garry Shandling, comedian and actor;

- Marc Benioff, founder of Salesforce.com;

- Jim Yong Kim, former president of the World Bank;

- John Croft, co-creator of Dragon Dreaming;

- Leila Seth, author and Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court; and

- Stephanie Kaza, environmentalist.

Return to Vietnam[edit]

In 2005, after lengthy negotiations, the Vietnamese government allowed Nhất Hạnh to return for a visit. He was also allowed to teach there, publish four of his books in Vietnamese, and travel the country with monastic and lay members of his Order, including a return to his root temple, Tu Hieu Temple in Huế.[6][40]

The trip was not without controversy. Thich Vien Dinh, writing on behalf of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (considered illegal by the Vietnamese government), called for Nhất Hạnh to make a statement against the Vietnam government's poor record on religious freedom. Vien Dinh feared that the Vietnamese government would use the trip as propaganda, suggesting that religious freedom is improving there, while abuses continue.[41][42][43]

Despite the controversy, Nhất Hạnh returned to Vietnam in 2007, while two senior officials of the banned Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV) remained under house arrest. The UBCV called his visit a betrayal, symbolizing his willingness to work with his co-religionists' oppressors.

Võ Văn Ái, a UBCV spokesman, said, "I believe Thích Nhất Hạnh's trip is manipulated by the Hanoi government to hide its repression of the Unified Buddhist Church and create a false impression of religious freedom in Vietnam."[44]

The Plum Village Website states that the three goals of his 2007 trip to Vietnam were to support new monastics in his Order; to organize and conduct "Great Chanting Ceremonies" intended to help heal remaining wounds from the Vietnam War; and to lead retreats for monastics and laypeople. The chanting ceremonies were originally called "Grand Requiem for Praying Equally for All to Untie the Knots of Unjust Suffering", but Vietnamese officials objected, calling it unacceptable for the government to "equally" pray for soldiers in the South Vietnamese army or U.S. soldiers. Nhất Hạnh agreed to change the name to "Grand Requiem For Praying".[44]

Other[edit]

In 2014, major Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Anglican, Catholic and Orthodox Christian leaders met to sign a shared commitment against modern-day slavery; the declaration they signed calls for the elimination of slavery and human trafficking by 2020. Nhất Hạnh was represented by Chân Không.[45]

Health[edit]

In November 2014, Nhất Hạnh experienced a severe brain hemorrhage and was hospitalized.[46][47] After months of rehabilitation, he was released from the stroke rehabilitation clinic at Bordeaux Segalen University, in France. On July 11, 2015, he flew to San Francisco to speed his recovery with an aggressive rehabilitation program at UCSF Medical Center.[48] He returned to France on January 8, 2016.[49]

After spending 2016 in France, Nhất Hạnh travelled to Thai Plum Village.[50] He has continued to see both Eastern and Western specialists while in Thailand,[50] but is unable to speak.[50]

On 2 November 2018, a press release from the Plum Village community confirmed that Nhất Hạnh, then aged 92, had returned to Vietnam a final time and will live at Từ Hiếu Temple for "his remaining days". In a meeting with senior disciples, he had "clearly communicated his wish to return to Vietnam using gestures, nodding and shaking his head in response to questions."[7] A representative for Plum Village, Sister True Dedication, has described his life in Vietnam (referring to him as "Thay" which is Vietnamese for "Teacher"):

Approach[edit]

Thích Nhất Hạnh's approach has been to combine a variety of teachings of Early Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhist traditions of Yogācāra and Zen, and ideas from Western psychology to teach mindfulness of breathing and the four foundations of mindfulness, offering a modern light on meditation practice. His presentation of the Prajnaparamita in terms of "interbeing" has doctrinal antecedents in the Huayan school of thought,[52] which "is often said to provide a philosophical foundation" for Zen.[53]

In September 2014, shortly before his stroke, Nhất Hạnh completed new English and Vietnamese translations of the Heart Sutra, one of the most important sutras in Mahayana Buddhism.[54] In a letter to his students,[54] he said he wrote these new translations because he thought that poor word choices in the original text had resulted in significant misunderstandings of these teachings for almost 2,000 years.

Nhất Hạnh has also been a leader in the Engaged Buddhism movement[1] (he is credited with coining the term[55]), promoting the individual's active role in creating change. He credits the 13th-century Vietnamese king Trần Nhân Tông with originating the concept. Trần abdicated his throne to become a monk and founded the Vietnamese Buddhist school of the Bamboo Forest tradition.[56]

Names applied to him[edit]

The Vietnamese name Thích (釋) is from "Thích Ca" or "Thích Già" (釋迦, "of the Shakya clan").[13] All Buddhist monastics in East Asian Buddhism adopt this name as their surname, implying that their first family is the Buddhist community. In many Buddhist traditions, there is a progression of names a person can receive. The first, the lineage name, is given when a person takes refuge in the Three Jewels. Nhất Hạnh's lineage name is Trừng Quang (澄光, "Clear, Reflective Light"). The next is a dharma name, given when a person takes additional vows or is ordained as a monastic. Nhất Hạnh's dharma name is Phùng Xuân (逢春, "Meeting Spring"). Dharma titles are also sometimes given; Nhất Hạnh's dharma title is Nhất Hạnh.[13]

Neither Nhất (一) nor Hạnh (行)—which approximate the roles of middle name or intercalary name and given name, respectively, when referring to him in English—was part of his name at birth. Nhất (一) means "one", implying "first-class", or "of best quality"; Hạnh (行) means "action", implying "right conduct" or "good nature." Nhất Hạnh has translated his Dharma names as Nhất = One, and Hạnh = Action. Vietnamese names follow this naming convention, placing the family or surname first, then the middle or intercalary name, which often refers to the person's position in the family or generation, followed by the given name.[57]

Nhất Hạnh's followers often call him Thầy ("master; teacher"), or Thầy Nhất Hạnh. Any Vietnamese monk or nun in the Mahayana tradition can be addressed as "thầy". Vietnamese Buddhist monks are addressed thầy tu ("monk") and nuns are addressed as sư cô ("sister") or sư bà ("elder sister"). On the Vietnamese version of the Plum Village website, he is also called Thiền Sư Nhất Hạnh ("Zen Master Nhất Hạnh").[58]

Relations with Vietnamese governments[edit]

Nhất Hạnh's relationship with the government of Vietnam has varied over the years. He stayed away from politics, but did not support the South Vietnamese government's policies of Catholicization. He questioned American involvement, which put him at odds with the Saigon leadership.[59][60] In 1975, he fled the country, not to return till 2005.

His relations with the communist government ruling Vietnam is also edgy, due to its atheism and hostility to religious freedom, though he has little interest in politics. The communist government is therefore skeptical of him, distrusts his work with the overseas Vietnamese population, and has several times restricted his praying requiem.[44] Nonetheless, his popularity has often affected the government's policies, and it has decided not to arrest him.

Awards and honors[edit]

Nobel laureate Martin Luther King, Jr. nominated Nhất Hạnh for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967.[23] The prize was not awarded that year.[61] Nhất Hạnh was awarded the Courage of Conscience award in 1991.[62]

Nhất Hạnh received 2015's Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award.[63][64]

In November 2017, the Education University of Hong Kong conferred an honorary doctorate upon Nhất Hạnh for his "life-long contributions to the promotion of mindfulness, peace and happiness across the world". As he was unable to attend the ceremony in Hong Kong, a simple ceremony was held on 29 August 2017 in Thailand, where John Lee Chi-kin, vice-president (academic) of EdUHK, presented the honorary degree certificate and academic gown to Nhất Hạnh on the university's behalf.[65][66]

Film[edit]

Nhất Hạnh has been featured in many films, including The Power of Forgiveness, shown at the Dawn Breakers International Film Festival[67].

He also appears in the 2017 documentary Walk with Me directed by Marc J Francis and Max Pugh, and supported by Oscar-winner Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu.[68] Filmed over three years, Walk With Me focuses on the Plum Village monastics' daily life and rituals, with Benedict Cumberbatch narrating passages from "Fragrant Palm Leaves" in voiceover.[69] The film was released in 2017, premiering at SXSW Festival.[68]

Graphic Novel[edit]

Along with Alfred Hassler and Chân Không, Nhất Hạnh is the subject of the 2013 graphic novel The Secret of the 5 Powers.[70]

Writings[edit]

- Vietnam: Lotus in a sea of fire. New York, Hill and Wang. 1967.

- Being Peace, Parallax Press, 1987, ISBN 0-938077-00-7

- The Sun My Heart', Parallax Press, 1988, ISBN 0-938077-12-0

- Our Appointment with Life: Sutra on Knowing the Better Way to Live Alone, Parallax Press, 1990, ISBN 1-935209-79-5

- The Miracle of Mindfulness, Rider Books, 1991, ISBN 978-0-7126-4787-8

- Old Path White Clouds: Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha, Parallax Press, 1991, ISBN 81-216-0675-6

- Peace Is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life, Bantam reissue, 1992, ISBN 9780553351392

- The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion, Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Diamond Sutra, Parallax Press, 1992, ISBN 0-938077-51-1

- Hermitage Among the Clouds, Parallax Press, 1993, ISBN 0-938077-56-2

- Zen Keys: A Guide to Zen Practice, Harmony, 1994, ISBN 978-0-385-47561-7

- Cultivating The Mind Of Love, Full Circle, 1996, ISBN 81-216-0676-4

- The Heart Of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra, Full Circle, 1997, ISBN 81-216-0703-5, ISBN 9781888375923 (2005 Edition)

- Transformation and Healing: Sutra on the Four Establishments of Mindfulness, Full Circle, 1997, ISBN 81-216-0696-9

- Living Buddha, Living Christ, Riverhead Trade, 1997, ISBN 1-57322-568-1

- True Love: A Practice for Awakening the Heart, Shambhala Publications, 1997, ISBN 1-59030-404-7

- Fragrant Palm Leaves: Journals, 1962–1966, Riverhead Trade, 1999, ISBN 1-57322-796-X

- Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers, Riverhead Books, 1999, ISBN 1-57322-145-7

- The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching, Broadway Books, 1999, ISBN 0-7679-0369-2

- The Miracle of Mindfulness: A Manual on Meditation, Beacon Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8070-1239-4 (Vietnamese: Phép lạ c̉ua sư t̉inh thưc).

- The Raft Is Not the Shore: Conversations Toward a Buddhist/Christian Awareness, Daniel Berrigan (Co-author), Orbis Books, 2000, ISBN 1-57075-344-X

- The Path of Emancipation: Talks from a 21-Day Mindfulness Retreat, Unified Buddhist Church, 2000, ISBN 81-7621-189-3

- A Pebble in Your Pocket, Full Circle Publishing, 2001, ISBN 81-7621-188-5

- Thich Nhat Hanh: Essential Writings, Robert Ellsberg (Editor), Orbis Books, 2001, ISBN 1-57075-370-9

- Anger: Wisdom for Cooling the Flames, Riverhead Trade, 2002, ISBN 1-57322-937-7

- Be Free Where You Are, Parallax Press, 2002, ISBN 1-888375-23-X

- No Death, No Fear, Riverhead Trade reissue, 2003, ISBN 1-57322-333-6

- Touching the Earth: Intimate Conversations with the Buddha, Parallax Press, 2004, ISBN 1-888375-41-8

- Teachings on Love, Full Circle Publishing, 2005, ISBN 81-7621-167-2

- Understanding Our Mind, HarperCollins, 2006, ISBN 978-81-7223-796-7

- Buddha Mind, Buddha Body: Walking Toward Enlightenment, Parallax Press, 2007, ISBN 1-888375-75-2

- The Art of Power, HarperOne, 2007, ISBN 0-06-124234-9

- Under the Banyan Tree, Full Circle Publishing, 2008, ISBN 81-7621-175-3

- Mindful Movements: Ten Exercises for Well-Being, Parallax Press 2008, ISBN 978-1-888375-79-4

- The Blooming of a Lotus, Beacon Press, 2009, ISBN 9780807012383

- Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life. HarperOne. 2010. ISBN 978-0-06-169769-2.

- Reconciliation: Healing the Inner Child, Parallax Press, 2010, ISBN 1-935209-64-7

- You Are Here: Discovering the Magic of the Present Moment, Shambhala Publications, 2010, ISBN 978-1590308387

- The Novice: A Story of True Love, HarperCollins, 2011, ISBN 978-0-06-200583-0

- Works by or about Thích Nhất Hạnh in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Your True Home: The Everyday Wisdom of Thich Nhat Hanh, Shambhala Publications, 2011, ISBN 978-1-59030-926-1

- Fear: Essential Wisdom for Getting Through the Storm, HarperOne, 2012, ISBN 978-1846043185

- The Pocket Thich Nhat Hanh, Shambhala Pocket Classics, 2012, ISBN 978-1-59030-936-0

- Love Letter to the Earth, Parallax Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1937006389

- The Art of Communicating, HarperOne, 2013, ISBN 978-0-06-222467-5

- How to Sit, Parallax Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1937006587

- How to Eat, Parallax Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1937006723

- No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming Suffering, Parallax Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1937006853

- How to Love, Parallax Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1937006884

- Is nothing something? : kids' questions and zen answers about life, death, family, friendship, and everything in between, Parallax Press 2014, ISBN 978-1-937006-65-5

- Silence: The Power of Quiet in a World Full of Noise, HarperOne (1705), 2015, ASIN: B014TAC7GQ

- How to Relax, Parallax Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1941529089

- Old Path, White Clouds: Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha Blackstone Audio, Inc.; 2016, ISBN 978-1504615983

- At Home in the World: Stories and Essential Teachings from a Monk's Life, with Jason Deantonis (Illustrator), Parallax Press, 2016, ISBN 1941529429

- The Other Shore: A New Translation of the Heart Sutra with Commentaries, Palm Leaves Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1-941529-14-0

- How to Fight, Parallax Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1941529867

- The Art of Living: Peace and Freedom in the Here and Now, HarperOne, 2017, ISBN 978-0062434661

See also[edit]

- Buddhism in France

- Buddhism in the United States

- Buddhism in Vietnam

- List of peace activists

- Religion and peacebuilding

- Timeline of Zen Buddhism in the United States

- Walk With Me film

References[edit]

- ^ Buddhist monastery and Zen center; a secluded retreat originally intended for wandering monks

- ^ a b c d Carolan, Trevor (January 1, 1996). "Mindfulness Bell: A Profile of Thich Nhat Hanh". Lion's Roar. Retrieved August 14,2018.

- ^ Ford, James Ishmael (2006). Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen. Wisdom Publications. p. 90. ISBN 0-86171-509-8.

- ^ Taylor, Philip (2007). Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post-revolutionary Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 299. ISBN 9789812304407. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Religion & Ethics – Thich Nhat Hanh". BBC. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Nhu, Quan (2002). "Nhat Hanh's Peace Activities" in "Vietnamese Engaged Buddhism: The Struggle Movement of 1963–66"". Reprinted on the Giao Diem si. Retrieved September 13,2010. (2002)

- ^ a b Johnson, Kay (January 16, 2005). "A Long Journey Home". Time Asia Magazine (online version). Retrieved September 13,2010.

- ^ a b "Thich Nhat Hanh Returns Home". Plum Village. November 2, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ "The Father of Mindfulness Awaits the End of This Life". Time.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh". Plum Village. January 11, 2019.

- ^ Samar Farah (April 4, 2002). "An advocate for peace starts with listening". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Joan Halifax, Thích Nhất Hạnh (2004). "The Fruitful Darkness: A Journey Through Buddhist Practice and Tribal Wisdom". Grove Press. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

Being vegetarian here also means that we do not consume dairy and egg products, because they are products of the meat industry. If we stop consuming, they will stop producing.

- ^ ""Oprah Talks to Thich Nhat Hanh" from "O, The Oprah Magazine"". March 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Dung, Thay Phap (2006). "A Letter to Friends about our Lineage" (PDF). PDF file on the Order of Interbeing website. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ Cordova, Nathaniel (2005). "The Tu Hieu Lineage of Thien (Zen) Buddhism". Blog entry on the Woodmore Village website. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh". Published on the Community of Interbeing, UK website. Archived from the original on January 2, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Bổn, Thích Đồng (December 23, 2010). "Tiểu Sử Hòa Thượng Thích Đôn Hậu". Thư Viện Hoa Sen (in Vietnamese). Retrieved November 20, 2018.

...in 1951 when he was transmission master at An Quang temple, in that transmission ceremony Ven. Nhật Liên, Ven. Nhất Hạnh…. were ordinees.

- ^ Mau, Thich Chi (1999) "Application for the publication of books and sutras", letter to the Vietnamese Governmental Committee of Religious Affairs, reprinted on the Plum Village website. He is the Elder of the Từ Hiếu branch of the 8th generation of the Liễu Quán lineage in the 42nd generation of the Linji school (臨 濟 禪, Vietnamese: Lâm Tế)

- ^ a b c d e f Miller, Andrea (September 30, 2016). "Peace in Every Step". Lion's Roar. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Zahn, Max (September 30, 2015). "Talking Buddha, Talking Christ". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved October 1,2015.

- ^ "Nhat Hanh is my Brother". Buddhist Door. May 1, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ^ "Searching for the Enemy of Man" in Nhat Nanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien". Dialogue. Saigon: La Boi. 1965. pp. 11–20. Retrieved September 13, 2010., Archived on the African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War website

- ^ Speech made by Martin Luther King, Jr. at the Riverside Church, NYC (April 4, 1967). "Beyond Vietnam". Archived on the African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War website. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ a b King, Martin Luther, Jr. (letter) (January 25, 1967). "Nomination of Thich Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize". Archived on the Hartford Web Publishing website. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Nobel Prize Official website "Facts on the Nobel Peace Prize."The names of the nominees cannot be revealed until 50 years later, but the Nobel Peace Prize committee does reveal the number of nominees each year."

- ^ Nobel Prize website – Nomination Process "The statutes of the Nobel Foundation restrict disclosure of information about the nominations, whether publicly or privately, for 50 years. The restriction concerns the nominees and nominators, as well as investigations and opinions related to the award of a prize."

- ^ Steinfels, Peter (September 19, 1993). "At a Retreat, a Zen Monk Plants the Seeds of Peace". The New York Times. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh". Integrative Spirituality. Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ [1] The Vietnam Center and Archive: "Situation Appraisal of Buddhism as a Political Force During Current Election Period Extending through September 1967"

- ^ "The Five Mindfulness Trainings". December 28, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ "The Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings of the Order of Interbeing". December 28, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ "Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism Inc. Web Site". Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "Information about Practice Centers from the official Community of Mindful Living site". Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ webteam. "About the European Institute of Applied Buddhism". Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "2016-2017 Annual Highlights from the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation". Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ a b "A Practice Center in the Tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh". deerparkmonastery.org.

- ^ "Colors of Compassion is a documentary film". Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "Article: ''Thich Nhat Hahn Leads Retreat for Members of Congress'' (2004) Faith and Politics Institute website". Faithandpolitics.org. May 14, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ Frank Bures. "Bures, Frank (2003) ''Zen and the Art of Law Enforcement'' – ''Christian Science Monitor''". Csmonitor.com. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ ""Thich Nhat Hanh on Burma", Buddhist Channel, accessed 11/5/2007". Buddhistchannel.tv. October 20, 2007. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ Warth, Gary (2005). "Local Buddhist Monks Return to Vietnam as Part of Historic Trip". North County Times (re-published on the Buddhist Channel news website). Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "Buddhist monk requests Thich Nhat Hanh to see true situation in Vietnam". Letter from Thich Vien Dinh as reported by the Buddhist Channel news website. Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, 2005. 2005. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "Vietnam: International Religious Freedom Report". U.S. State Department. 2005. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Kenneth Roth; executive director (1995). "Vietnam: The Suppression of the Unified Buddhist Church". Vol.7, No.4. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Kay (March 2, 2007). "The Fighting Monks of Vietnam". Time Magazine. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "Pope Francis And Other Religious Leaders Sign Declaration Against Modern Slavery". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "Our Beloved Teacher in Hospital". Retrieved November 12,2014.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh Hospitalized for Severe Brain Hemorrhage". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. November 13, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ "An Update on Thay's Health: 14th July 2015". Plum Village Monastery. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ "An Update on Thay's Health: 8th January 2016". Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c "On his 92nd birthday, a Thich Nhat Hanh post-stroke update". Lion's Roar. October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11,2018.

- ^ Littlefair, Sam (January 25, 2019). "Thich Nhat Hanh's health "remarkably stable," despite report in TIME". Lion's Roar. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ McMahan, David L. The Making of Buddhist Modernism. Oxford University Press: 2008 ISBN 978-0-19-518327-6 pg 158

- ^ Williams, Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations2nd ed.Taylor & Francis, 1989, page 144

- ^ a b "New Heart Sutra translation by Thich Nhat Hanh". Plum Village Web Site. September 13, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- ^ Duerr, Maia (March 26, 2010). "An Introduction to Engaged Buddhism". PBS. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Hunt-Perry, Patricia; Fine, Lyn. "All Buddhism is Engaged: Thich Nhat Hanh and the Order of Interbeing". In Queen, Christopher S. (ed.). Engaged Buddhism in the West. Wisdom Publications. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0861711598.

- ^ Geotravel Research Center, Kissimmee, Florida (1995). "Vietnamese Names". Excerpted from "Culture Briefing: Vietnam". Things Asian website. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "Title attributed to TNH on the Vietnamese Plum Village site" (in Vietnamese). Langmai.org. December 31, 2011. Retrieved June 16,2013.

- ^ "Searching for the Enemy of Man" in Nhat Nanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien". Dialogue. Saigon: La Boi. 1965. pp. 11–20. Retrieved September 13, 2010., Archived on the African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War website

- ^ Speech made by Martin Luther King, Jr. at the Riverside Church, NYC (April 4, 1967). "Beyond Vietnam". Archived on the African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War website. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "Facts on the Nobel Peace Prize". Nobel Media. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ "The Peace Abbey – Courage of Conscience Recipients List". Archived from the original on February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Thich Nhat Hanh to receive Catholic "Peace on Earth" award". Lion's Roar. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Diocese of Davenport (October 23, 2015). "Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award recipient announced". Archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- ^ "The Education University of Hong Kong (EduHK) Press Release".

- ^ "The Education University of Hong Kong (EdUHK) Facebook".

- ^ "First line up". Dawn Breakers International Film Festival (DBIFF). December 5, 2009. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Barraclough, Leo; Barraclough, Leo (March 9, 2017). "Alejandro G. Inarritu on Mindfulness Documentary 'Walk With Me' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Catsoulis, Jeannette (August 17, 2017). "Review: 'Walk With Me,' an Invitation From Thich Nhat Hanh". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Sperry, Rod Meade (May 2013), "3 Heroes, 5 Powers", Lion's Roar, 21 (5): 68–73

External links[edit]

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (May 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Parallax Press – publishing house founded by Thich Nhat Hanh

- Sangha Directory – List of communities (Mindfulness Practice Groups) practicing in Thich Nhat Hanh's tradition

- Plum Village – Thich Nhat Hanh's main monastery and practice center, located about 85 km east of Bordeaux, France

- Vietnamese website of Plum Village

- French website of Plum Village

- Deer Park Monastery – located in Escondido, California

- Magnolia Grove Monastery – practice center, located near Memphis, TN

- Order of Interbeing

- I Am Home – Community of Mindful Living; home of the "Mindfulness Bell" magazine with news, articles, and talks by Thich Nhat Hanh and other Order of Interbeing members

- Thích Nhất Hạnh's Five Mindfulness Trainings & the Fourteen Precepts

대여

대여