One of the things that scares me about the Quakers is the bureaucratic approach. It has always scared me because bureaucracies lead to all kinds of crazy decisions and nobody has to take responsibility.

Well this new new Guardian article may conform my fears as "The Quakers consider dropping God from their meetings guidance as it makes some feel uncomfortable. This is the new religiosity".

More comfortable? Wouldn't you think visitors to a meeting house would be tolerant enough to accept sparing mention of God and other things important to the Quakers faith?

The Quakers risk falling into a trap of relativism (and I believe post-modernism) that will be the end of its relevance.

If this is the position that Australian Quakers eventually take, I would rather side with the African Quakers and put up with their evangelism. Because policing the use of the word "God" in what is basically a church would be absurd.

Please speak up, don't just allow bureaucratic cogs to turn. Christ was not a bureaucrat, he spoke truth to power.

Best wishes to everyone

Mike

==================

The Quakers are right. We don’t need God | Simon Jenkins

----------

The Quakers are right. We don’t need God

Simon Jenkins

Simon Jenkins

The group is considering dropping God from its meetings guidance as it makes some feel uncomfortable. This is the new religiosity

Fri 4 May 2018 16.00 AESTLast modified on Sat 5 May 2018 01.24 AEST

Shares

4,840

Comments1,441

----------

The Quakers are right. We don’t need God

Simon Jenkins

Simon JenkinsThe group is considering dropping God from its meetings guidance as it makes some feel uncomfortable. This is the new religiosity

Fri 4 May 2018 16.00 AESTLast modified on Sat 5 May 2018 01.24 AEST

Shares

4,840

Comments1,441

The Quaker meeting house at Carperby in Wensleydale. Photograph: Alamy

----------

The Quakers are clearly on to something. At their annual get-together this weekend they are reportedly thinking of dropping God from their “guidance to meetings”. The reason, said one of them, is because the term “makes some Quakers feel uncomfortable”. Atheists, according to a Birmingham University academic, comprise a rising 14% of professed Quakers, while a full 43% felt “unable to profess a belief in God”. They come to meetings for fellowship, rather than for higher guidance. The meeting will also consider transgenderism, same-sex marriage, climate change and social media. Religion is a tiring business.

I am not a Quaker or religious, but I have been to Quaker meetings, usually marriages or funerals, and found them deeply moving. The absence of ritual, the emphasis on silence and thought and the witness of “friends” seemed starkly modernist. Meeting houses can be beautiful spaces. The loveliest I know dates from 1700 and is lost in deep woods near Meifod, Powys. It is a place of the purest serenity, miles from any road and with only birdsong to blend with inner reflection.

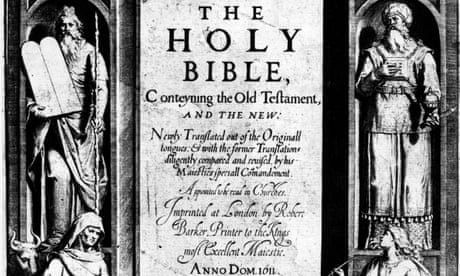

King James Bible's classic English text revealed to include work by French scholar

The Quakers’ lack of ceremony and liturgical clutter gives them a point from which to view the no man’s land between faith and non-faith that is the “new religiosity”. A dwindling 40% of Britons claim to believe in some form of God, while a third say they are atheists. But that leaves over a quarter in a state of vaguely agnostic “spirituality”. Likewise, while well over half of Americans believe in the biblical God, nearly all believe in “a higher power or spiritual force”.

What these words mean is now the subject of intense debate. What are these spirits in which these people profess to believe, and how might they be appeased? It is clear that most people no longer see them as residing in a church. Yet many still turn to churches in emergencies or times of trouble, when the world seems otherwise inexplicable. This was noted after the high-profile deaths of Princess Diana and Jade Goody. As the sociologist Grace Davie put it in her book Religion in Britain, the church is a sort of public utility, a fire station or pop-up A&E unit.

To Davie, many of these people are declaring a “vicarious religion”, or what she calls “believing not belonging”. They do not like a church’s faux collegiality, the hand-shaking, happy-clapping and sense of entrapment. They do not really seek God, rather a mental and physical space to sort out their thoughts, somewhere to find “anonymity, the option to come and go without explanation or greeting … to move from one stage of commitment to another”.

This is taken to explain the continuing success of cathedrals, where attendances have risen while those in churches has fallen. It seems cathedrals meet a quasi-secular searching for solitude and inner peace, stimulated by great architecture and music. Above all, they offer anonymity. A character in last week’s The Archers sought solace in fictional “Felpersham” cathedral, to find “somewhere she could be anonymous”. A latest British Journal of General Practice survey suggests doctors are increasingly being used as “new clergy” by people who are not ill but seeking something to “give meaning and purpose to life”. It would take a brave GP to prescribe a dose of matins once a day. But something “spiritual” is needed.

The boom in psychotherapy is no secret. As religion declines, so emerges a craving for therapy. The 12-step movement of alcoholics and narcotics “anonymous” has much in common with Quakerism, notably the emphasis on non-authoritarian fellowship. Beyond lie the wilder shores of mindfulness, meditation, happiness courses and “holistic spirituality”. All this suggests that the purely physical aspects of our being do not always meet the needs of a fully rounded person.

The Quakers have always been remarkable. They were a disruptive force in 17th-century religion. They thrived through being persecuted for denying allegiance to the Church of England. Their exclusion bred Britain’s first industrialists, bankers and confectioners, not to mention the famous Quaker Oats. Quakerism has declined of late, perhaps because there is no fortune in rebelling against any church. You can find “friends” on the web and introspection on the NHS.

If Quakers now find God “uncomfortable” I can hear cries from pulpits that discomfort is the point of Christianity. Comfort is in the afterlife, and marketing it has been the church’s unique selling proposition since Luther and papal indulgences. To Luther it was a con. What is not a con is humanity’s quest for comfort in the here and now, for therapy in the widest sense of the word.

The sublimity of Dolobran meeting house and the exhilaration of Ely cathedral offer more than an emotional A&E unit. They offer places so uplifting that anyone can find it in themselves to sit, think, clear their heads and order their thoughts. There is no need for gods or religion to rest and be refreshed.

To that, Quakerism has added the experience of standing up and expressing doubts, fears and joys amid a company of “friends”, who respond only with their private silence. The therapy is that of shared experience. Clear God from the room, and the Quakers are indeed on to something.

• Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist

----------

The Quakers are clearly on to something. At their annual get-together this weekend they are reportedly thinking of dropping God from their “guidance to meetings”. The reason, said one of them, is because the term “makes some Quakers feel uncomfortable”. Atheists, according to a Birmingham University academic, comprise a rising 14% of professed Quakers, while a full 43% felt “unable to profess a belief in God”. They come to meetings for fellowship, rather than for higher guidance. The meeting will also consider transgenderism, same-sex marriage, climate change and social media. Religion is a tiring business.

I am not a Quaker or religious, but I have been to Quaker meetings, usually marriages or funerals, and found them deeply moving. The absence of ritual, the emphasis on silence and thought and the witness of “friends” seemed starkly modernist. Meeting houses can be beautiful spaces. The loveliest I know dates from 1700 and is lost in deep woods near Meifod, Powys. It is a place of the purest serenity, miles from any road and with only birdsong to blend with inner reflection.

King James Bible's classic English text revealed to include work by French scholar

The Quakers’ lack of ceremony and liturgical clutter gives them a point from which to view the no man’s land between faith and non-faith that is the “new religiosity”. A dwindling 40% of Britons claim to believe in some form of God, while a third say they are atheists. But that leaves over a quarter in a state of vaguely agnostic “spirituality”. Likewise, while well over half of Americans believe in the biblical God, nearly all believe in “a higher power or spiritual force”.

What these words mean is now the subject of intense debate. What are these spirits in which these people profess to believe, and how might they be appeased? It is clear that most people no longer see them as residing in a church. Yet many still turn to churches in emergencies or times of trouble, when the world seems otherwise inexplicable. This was noted after the high-profile deaths of Princess Diana and Jade Goody. As the sociologist Grace Davie put it in her book Religion in Britain, the church is a sort of public utility, a fire station or pop-up A&E unit.

To Davie, many of these people are declaring a “vicarious religion”, or what she calls “believing not belonging”. They do not like a church’s faux collegiality, the hand-shaking, happy-clapping and sense of entrapment. They do not really seek God, rather a mental and physical space to sort out their thoughts, somewhere to find “anonymity, the option to come and go without explanation or greeting … to move from one stage of commitment to another”.

This is taken to explain the continuing success of cathedrals, where attendances have risen while those in churches has fallen. It seems cathedrals meet a quasi-secular searching for solitude and inner peace, stimulated by great architecture and music. Above all, they offer anonymity. A character in last week’s The Archers sought solace in fictional “Felpersham” cathedral, to find “somewhere she could be anonymous”. A latest British Journal of General Practice survey suggests doctors are increasingly being used as “new clergy” by people who are not ill but seeking something to “give meaning and purpose to life”. It would take a brave GP to prescribe a dose of matins once a day. But something “spiritual” is needed.

The boom in psychotherapy is no secret. As religion declines, so emerges a craving for therapy. The 12-step movement of alcoholics and narcotics “anonymous” has much in common with Quakerism, notably the emphasis on non-authoritarian fellowship. Beyond lie the wilder shores of mindfulness, meditation, happiness courses and “holistic spirituality”. All this suggests that the purely physical aspects of our being do not always meet the needs of a fully rounded person.

The Quakers have always been remarkable. They were a disruptive force in 17th-century religion. They thrived through being persecuted for denying allegiance to the Church of England. Their exclusion bred Britain’s first industrialists, bankers and confectioners, not to mention the famous Quaker Oats. Quakerism has declined of late, perhaps because there is no fortune in rebelling against any church. You can find “friends” on the web and introspection on the NHS.

If Quakers now find God “uncomfortable” I can hear cries from pulpits that discomfort is the point of Christianity. Comfort is in the afterlife, and marketing it has been the church’s unique selling proposition since Luther and papal indulgences. To Luther it was a con. What is not a con is humanity’s quest for comfort in the here and now, for therapy in the widest sense of the word.

The sublimity of Dolobran meeting house and the exhilaration of Ely cathedral offer more than an emotional A&E unit. They offer places so uplifting that anyone can find it in themselves to sit, think, clear their heads and order their thoughts. There is no need for gods or religion to rest and be refreshed.

To that, Quakerism has added the experience of standing up and expressing doubts, fears and joys amid a company of “friends”, who respond only with their private silence. The therapy is that of shared experience. Clear God from the room, and the Quakers are indeed on to something.

• Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist

-------------