Basic income - Wikipedia

Basic income

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a system of unconditional income to every citizen. For the specific form financed on the profits of publicly owned enterprises, see social dividend. For social welfare based on means tests, see Guaranteed minimum income.

Not to be confused with living wage or minimum wage.

On 4 October 2013, Swiss activists from Generation Grundeinkommen organized a performance in Bern in which roughly 8 million coins, one coin representing one person out of Switzerland's population, were dumped on a public square. This was done in celebration of the successful collection of more than 125,000 signatures, forcing the government to hold a referendum on whether or not to incorporate the concept of basic income in the Federal constitution. The measure did not pass, with 76.9% voting against basic income.[1]

A basic income (also called basic income guarantee, citizen's income, unconditional basic income, universal basic income (UBI), basic living stipend (BLS) or universal demogrant) is typically described as a new kind of welfare program in which all citizens (or permanent residents) of a country receive a regular, livable and unconditional sum of money, from the government. From that follows, among other things, that there is no state requirement to work or to look for work in such a society. The payment is also, in such a pure basic income, totally independent of any other income.[2][3][4]An unconditional income that is sufficient to meet a person's basic needs (at or above the poverty line), is called full basic income, while if it is less than that amount, it is called partial. Basic income can be implemented nationally, regionally or locally. Some welfare systems are related to basic income but have certain conditions. For example, Bolsa Família in Brasil is restricted to poor families and the children are obligated to attend school.[5] A related welfare system is negative income tax. Like basic income, it guarantees everyone (where everyone can mean, for example, all adult citizens of a country) a certain amount of regular income. But unlike a basic income with the same amount for all negative tax means that the amount is gradually reduced with higher labor income.

Contents [hide]

1History

2Perspectives in the basic income debate

2.1Transparency and administrative efficiency

2.2Poverty reduction

2.3Freedom

2.4Gender equality

2.5Arguments from different ideologies

2.6Employment

2.7Bad behavior

2.8Wage slavery and alienation

2.9Economic growth

2.10Automation

2.11Economic critique

2.12Basic income as a part of a post-capitalistic economic system

3National debates

3.1Germany

3.2India

4General ideas about the funding

4.1Reducing or removing of the current welfare systems

4.2Income tax

4.3Tax on consumption (VAT)

4.4Other taxes

4.5Monetary reform

4.6Reduction of medical costs

4.7Taxing the data giants

5More specific funding proposals

5.1United States

5.2Scott Santens, basic income activist

6Existing basic income and related systems

7Prominent advocates

8Petitions, polls and referendums

9See also

10References

11Further reading

12External links

History[edit]

See also: Basic income around the world

The idea of a state-run basic income dates back to the late 18th century when English radical Thomas Spence and American revolutionary Thomas Paine both declared their support for a welfare system in which all citizens were guaranteed a certain income. In the 19th century and until the 1960s the debate on basic income was limited, but in the 1960s and 1970s the United States and Canada conducted several experiments with negative income taxation, a related welfare system. From the 1980s and onwards the debate in Europe took off more broadly and since then it has expanded to many countries around the world. A few countries have implemented large-scale welfare systems that are related to basic income, such as the Permanent Fund in Alaska and Bolsa Família in Brasil. From 2008 and onwards there has also been several experiments with basic income and related systems. Especially in countries with an existing welfare state a part of the funding assumably comes from replacing the current welfare arrangements, or a part of it, such as different grants for unemployed people. Apart from that there are several ideas and proposals regarding the rest of the financing, as well as different ideas about the level and other aspects.

The idea of an unconditional basic income, given to all citizens in a state (or all adult citizens), was first presented near the middle of the 19th century. But long before that there were ideas of a so-called minimum income, the idea of a one-off grant and the idea of a social insurance (which still is a key feature of all modern welfare states, with insurances for and against unemployment, sickness, parenthood, accidents, old age and so forth).[citation needed]

The minimum income, the idea to eradicate poverty by targeting the poor, is in contradiction with basic income given "to all", but nevertheless share some underlying ideas about the state's or the city's welfare responsibilities towards its citizens. Johannes Ludovicus Vives (1492–1540), for example, proposed that the municipal government should be responsible for securing a subsistence minimum to all its residents, "not on grounds of justice but for the sake of a more effective exercise of morally required charity". However, to be entitled to poor relief the person’s poverty must not, he argued, be undeserved, but he or she must "deserve the help he or she gets by proving his or her willingness to work."[6]

The first to develop the idea of a social insurance was Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794). After playing a prominent role in the French Revolution, he was imprisoned and sentenced to death. While in prison, he wrote the Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain (published posthumously by his widow in 1795), whose last chapter described his vision of a social insurance and how it could reduce inequality, insecurity and poverty. Condorcet mentioned, very briefly, the idea of a benefit to all children old enough to start working by themselves and to start up a family of their own. He is not known to have said or written anything else on this proposal, but his close friend and fellow member of the Convention Thomas Paine (1737–1809) developed the idea much further, a couple of years after Condorcet’s death.

The first social movement for basic income developed around 1920 in the United Kingdom. Its proponents included Bertrand Russell, Dennis Milner (with wife) and Clifford H. Douglas.

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) argued for a new social model that combined the advantages of socialism and anarchism, and that basic income should be a vital component in that new society.

Dennis Milner, a Quaker and a Labour Party member, published jointly with his wife Mabel, a short pamphlet entitled “Scheme for a State Bonus” (1918). There they argued for the "introduction of an income paid unconditionally on a weekly basis to all citizens of the United Kingdom". They considered it a moral right for everyone to have the means to subsistence, and thus it should not be conditional on work or willingness to work.

Clifford H. Douglas was an engineer who became concerned that most British citizens could not afford to buy the goods that were produced, despite the rising productivity in British industry. His solution to this paradox was a new social system called "social credit", a combination of monetary reform and basic income.

In 1944 and 1945, the Beveridge Committee, led by the British economist William Beveridge, developed a proposal for a comprehensive new welfare system of social insurance and selective grants. Committee member Lady Rhys-Williams argued for basic income. She was also the first to develop the negative income tax model.[7][8]

In the 1960s and 1970s, there were welfare debates in United States and Canada which included basic income. Six pilot projects were also conducted with negative income tax. Then US president Richard Nixon once even proposed a negative income tax in a bill to the US Congress. But the Congress eventually only approved a guaranteed income for the elderly and the disabled, not for all citizens.[9]

In the late 1970s and the 1980s, basic income was more or less forgotten in the United States, but on the other hand it started to gain some attraction in Europe. Basic Income European Network, later renamed to Basic Income Earth Network, was founded in 1986 and started to arrange international conferences every two years. From the 1980s, some people outside party politics and universities took interest. In West Germany, groups of unemployed people took a stance for the reform.[10]

From 2005–2010 and onwards, basic income again became a hot topic in many countries. Basic income is nowaday discussed from a variety of perspectives. But not least in the context of ongoing automation and robotisation, often with the argument that these trends will mean less paid work in the future, which in turn would create a need for a new welfare model. Several countries are planning for local or regional experiments with basic income and/or related welfare systems. The experiments in India, Finland and Canada, for example, have received international media attention. There have also been several polls about basic income, investigating the public support for the idea in different countries, and in 2016 a basic income proposal was rejected in Switzerland by 76.9% of the voters in a national referendum.

Perspectives in the basic income debate[edit]

Transparency and administrative efficiency[edit]

Basic income is potentially a much simpler and more transparent welfare system than existing in the welfare states today.[11] Instead of separate welfare programs (including unemployment insurance, child support, pensions, disability, housing support) it could be one income, or it could be a basic payment that welfare programs could add to.[12] This could require less paperwork and bureaucracy to check eligibility. The lack of means test or similar bureaucracy would allow for saving on social welfare, which could be put towards the grant. The Basic Income Earth Network(BIEN) claims that basic income costs less than current means-tested social welfare benefits, and has proposed an implementation that it claims to be financially viable.[13][14]

However, other proponents argue for adding basic income to existing welfare grants, rather than replacing them.

Poverty reduction[edit]

Advocates of basic income often argue that it has a potential to reduce or even eradicate poverty.[15]

Freedom[edit]

Philippe Van Parijs

Philippe Van Parijs has argued that basic income at the highest sustainable level is needed to support real freedom, or the freedom to do whatever one "might want to do".[16] By this, Van Parijs means that all people should be free to use the resources of the Earth and the "external assets" people make out of them to do whatever they want. Money is like an access ticket to use those resources, and so to make people equally free to do what they want with world assets, the government should give each individual as many such access tickets as possible—that is, the highest sustainable basic income.

Karl Widerquist and others have proposed a theory of freedom in which basic income is needed to protect the power to refuse work.[17] The theory goes like this:

If some other group of people controls resources necessary to an individual's survival, that individual has no reasonable choice other than to do whatever the resource-controlling group demands. Before the establishment of governments and landlords, individuals had direct access to the resources they needed to survive. But today, resources necessary to the production of food, shelter, and clothing have been privatized in such a way that some have gotten a share and others have not. Therefore, this argument goes, the owners of those resources owe compensation back to non-owners, sufficient at least for them to purchase the resources or goods necessary to sustain their basic needs. This redistribution must be unconditional because people can consider themselves free only if they are not forced to spend all their time doing the bidding of others simply to provide basic necessities to themselves and their families.[18] Under this argument, personal, political, and religious freedom are worth little without the power to say no. In this view, basic income provides an economic freedom, which—combined with political freedom, freedom of belief, and personal freedom—establish each individual's status as a free person.

Gender equality[edit]

The Scottish economist Ailsa McKay argued that basic income is a way to promote gender equality.[19][20] She noted in 2001 that "social policy reform should take account of all gender inequalities and not just those relating to the traditional labor market" and that "the citizens' basic income model can be a tool for promoting gender-neutral social citizenship rights."[19]

Arguments from different ideologies[edit]

Georgist views: Geolibertarians seek to synthesize propertarian libertarianism and a geoist (or Georgist) philosophy of land as unowned commons or equally owned by all people, citing the classical economic distinction between unimproved land and private property. The rental value of land is produced by the labors of the community and, as such, rightly belongs to the community at large and not solely to the landholder. A land value tax (LVT) is levied as an annual fee for exclusive access to a section of earth, which is collected and redistributed to the community either through public goods, such as public security or a court system, or in the form of a basic guaranteed income called a citizen's dividend. Geolibertarians view the LVT as a single tax to replace all other methods of taxation, which are deemed unjust violations of the non-aggression principle.

Right-wing views: Support for basic income has been expressed by several people associated with right-wing political views. While adherents of such views generally favor minimization or abolition of the public provision of welfare services, some have cited basic income as a viable strategy to reduce the amount of bureaucratic administration that is prevalent in many contemporary welfare systems. Others have contended that it could also act as a form of compensation for fiat currencyinflation.[21][22][23]

Feminist views: Feminists' views on the basic income can be loosely divided into two opposing views: one view which supports basic income, seeing it as a way of guaranteeing a minimum financial independence for women, and recognizing women's unpaid work in the home; and another view which opposes basic income, seeing it as having the potential to discourage women from participating in the workforce, and to reinforce traditional gender roles of women belonging in the private area and men in the public area.[24][25]

Employment[edit]

One argument against basic income is that if people have free and unconditional money, they will "get lazy" and not work as much as before.[26][27][28] Less work means less tax revenue, argue critics, and hence less money for the state and cities to fund public projects. If there is a disincentive to employment because of basic income, it is however expected that the magnitude of such a disincentive would depend on how generous the basic income were to be.

There have been some studies around the employment levels during the experiments with basic income and negative income tax, and similar systems. In the negative income tax-experiments in United States in the 1970s, for example, there were a five percent decline in the hours worked. The work reduction was largest for second earners in two-earner households and weakest for the main earner. It was also a higher reduction in hours working when the benefit was higher. The participants in these experiments, however, knew that the experiment was limited in time.[27] In the Mincome experiment in rural Dauphin, Manitoba, also in the 1970s, there were also a slight reduction in hours worked during the experiment. However, the only two groups who worked significantly less were new mothers and teenagers working to support their families. New mothers spent this time with their infant children, and working teenagers put significant additional time into their schooling.[29] Under Mincome, "the reduction of work effort was modest: about one per cent for men, three per cent for wives, and five per cent for unmarried women."[30]

Another study that contradicted such decline in work incentive was a pilot project implemented in 2008 and 2009 in the Namibian village of Omitara; the assessment of the project after its conclusion found that economic activity actually increased, particularly through the launch of small businesses, and reinforcement of the local market by increasing households' buying power.[31] However, the residents of Omitara were described as suffering "dehumanising levels of poverty" before the introduction of the pilot, and as such the project's relevance to potential implementations in developed economies is unknown.[32]

James Meade states that a return to full employment can only be achieved if, among other things, workers offer their services at a low enough price that the required wage for unskilled labor would be too low to generate a socially desirable distribution of income. He therefore concludes that a "citizen's income" is necessary to achieve full employment without suffering stagnant or negative growth in wages.[33]

If there is a disincentive to employment because of basic income, it is however expected that the magnitude of such a disincentive would depend on how generous the basic income were to be. Some campaigners in Switzerland have suggested a level that would only just be liveable, arguing that people would want to supplement it.[34]

Tim Worstall, a writer, blogger and Senior Fellow of the Adam Smith Institute,[35] has argued that traditional welfare schemes create a disincentive to work, because such schemes typically cause people to lose benefits at around the same rate that their income rises (a form of welfare trap where the marginal tax rate is 100 percent). He has asserted that this particular disincentive is not a property shared by basic income, as the rate of increase is positive at all incomes.[36]

Bad behavior[edit]

There are concerns that some people will spend their basic income on alcohol and drugs.[18][37] However, studies of the impact of direct cash transfer programs provide evidence to the contrary. A 2014 World Bank review of 30 scientific studies concludes that "concerns about the use of cash transfers for alcohol and tobacco consumption are unfounded".[38]

Wage slavery and alienation[edit]

Fox Piven argues that an income guarantee would benefit all workers by liberating them from the anxiety that results from the "tyranny of wage slavery" and provide opportunities for people to pursue different occupations and develop untapped potentials for creativity.[39] Gorz saw basic income as a necessary adaptation to the increasing automation of work, but also a way to overcome the alienation in work and life and to increase the amount of leisure time.[40]

Economic growth[edit]

Some proponents have argued that basic income can increase economic growthbecause it would sustain people while they invest in education to get interesting and well-paid jobs.[41][18] However, there is also a discussion of basic income within the degrowth movement, which argues against economic growth.[42]

Automation[edit]

The debates about basic income and automation are closely linked. For example, Mark Zuckerberg argues that automation will take away many jobs in coming years, and that basic income is especially needed because of that. Concerns about automation have prompted many in the high-technology industry to argue for basic income as an implication of their business models.

Many technologists believe that automation (among other things) is creating technological unemployment. Journalist Nathan Schneider first highlighted the turn of the "tech elite" to these ideas with an article in Vice magazine, which cited Marc Andreessen, Sam Altman, Peter Diamandis, and others.[43][44][45] Some studies about automation and jobs validate these concerns. The US White House, in a report to the US Congress, estimated that a worker earning less than $20 an hour in 2010 will eventually lose their job to a machine with 83% probability. Even workers earning as much as $40 an hour faced a probability of 31%.[44] With a rising unemployment rate, poor communities will become more impoverished worldwide. Proponents of universal basic income argue that it could solve many world problems like high work stress, and provide more opportunities and efficient and effective work. This claim is supported by some studies. In a study in Dauphin, Manitoba, only 13% of labor decreased from a much higher expected number.[46] In a study in several Indian villages, basic income in the region raised the education rate of young people by 25%.[47]

Besides technological unemployment, some tech-industry experts worry that automation will destabilize the labor market or increase economic inequality. One is example, Chris Hughes, co-founder of both Facebook and Economic Security Project. Automation has been happening for hundreds of years; it has not permanently reduced the employment rate but has constantly caused employment instability. It displaces workers who spend their lives learning skills that become outmoded and forces them into unskilled labor. Paul Vallée, a Canadian tech-entrepreneur and CEO of Pythian, argues that automation is at least as likely to increase poverty and reduce social mobility than it is to create ever-increasing unemployment rate. At the 2016 North American Basic Income Guarantee Congress in Winnipeg, Vallée examined slavery as a historical example of a period in which capital (African slaves) could do the same things that human labor (poor whites) could do. He found that slavery did not cause massive unemployment among poor whites, but instead increased economic inequality and lowered social mobility.[48]

Economic critique[edit]

Daron Acemoglu, Professor in economics at MIT, has expressed doubts about basic income with the following statement: "Current US status quo is horrible. A more efficient and generous social safety net is needed. But UBI is expensive and not generous enough."[49] Eric Maskin has stated that "a minimum income makes sense, but not at the cost of eliminating Social Security and Medicare".[50]

Basic income as a part of a post-capitalistic economic system[edit]

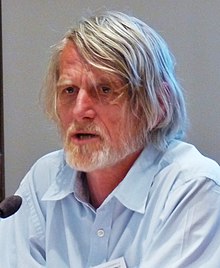

Erik Olin Wright, 2013.

Harry Shutt proposed basic income and other measures to make all or most enterprises collective rather than private. These measures would create a post-capitalist economic system.[51]

Erik Olin Wright characterizes basic income as a project for reforming capitalism into an economic system by empowering labor in relation to capital, granting labor greater bargaining power with employers in labor markets, which can gradually de-commodify labor by decoupling work from income. This would allow for an expansion in scope of the "social economy", by granting citizens greater means to pursue activities (such as the pursuit of art) that do not yield strong financial returns.[52]

James Meade advocated for a social dividend scheme to be funded by publicly owned productive assets.[53]Russell argued for a basic income alongside public ownership as a means to shorten the average working day and achieve full employment.[54]

Economists and sociologists have advocated for a form of basic income as a way to distribute economic profits of publicly owned enterprises to benefit the entire population (also referred to as a social dividend), where the basic income payment represents the return to each citizen on the capital owned by society. These systems would be directly financed from returns on publicly owned assets and are featured as major components of many models of market socialism.[55]

Guy Standing has proposed financing a social dividend from a democratically-accountable sovereign wealth fund built up primarily from the proceeds of a levy on rentier income derived from ownership or control of assets - physical, financial and intellectual.[56][57]

Herman Daly, considered as one of the founders of ecologism, argued primarily for a zero growth economy within the ecological limits of the planet. But to have such a green and sustainable economy, including basic economic welfare and security to all people, he wrote a lot about the need for structural reforms of the capitalistic system, including basic income, monetary reform, land value tax, trade reforms and higher eco-taxes (taxes on pollution and CO2). For him, basic income was thus part of a larger structural change of the economic system, towards a more green and sustainable system.

National debates[edit]

Germany[edit]

A commission of the German parliament discussed basic income in 2013 and concluded that it is "unrealizable" because:

it would cause a significant decrease in the motivation to work among citizens, with unpredictable consequences for the national economy

it would require a complete restructuring of the taxation, social insurance and pension systems, which will cost a significant amount of money

the current system of social help in Germany is regarded as more effective because it is more personalized: the amount of help provided depends on the financial situation of the recipient; for some socially vulnerable groups, the basic income could be insufficient

it would cause a vast increase in immigration

it would cause a rise in the shadow economy

the corresponding rise of taxes would cause more inequality: higher taxes would cause higher prices of everyday products, harming the finances of poor people

no viable way to finance basic income in Germany was found[58][59]

India[edit]

India has been considering basic income in India. On January 31, 2017, the Economic Survey of India included a 40-page chapter on UBI that outlined the 3 components of the proposed program: 1) universality, 2) unconditionality, 3) agency. The UBI proposal in India is framed with the intent of providing every citizen "a basic income to cover their needs," which is encompassed by the "universality" component. "Unconditionality" points to the accessibility of all to the basic income, without any means tests. The third component, "agency," refers to the lens through which the Indian government views the poor. According to the Survey, by treating the poor as agents rather than subjects, UBI "liberates citizens from paternalistic and clientelistic relationships with the state."

General ideas about the funding[edit]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: it just neeeds cleanup... Please help improve this section if you can. (December 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

The affordability of a basic income proposal relies on many factors, such as the costs of any public services it replaces, required tax increases, and less tangible auxiliary effects on government revenue or spending (for example a successful basic income scheme may reduce crime, thereby reducing required expenditure on policing and justice).[citation needed]

Reducing or removing of the current welfare systems[edit]

Basic income would substitute to a wide range of existing social welfare programmes, tax rebates, state subsidies and work activation spendings. All or a lot of those budgets (including administrative costs) could, at least in theory, be reallocated to finance basic income.[citation needed]

Income tax[edit]

Although basic income is paid to everyone universally, people whose earnings are above the mean income are net contributors to the basic income scheme, mainly through an income tax. In practice this means that the net cost of basic income is much lower than the raw cost calculated as a sum of monthly payments to the whole population.[citation needed] A 2012 affordability study in the Republic of Ireland by Social Justice Ireland found that basic income would be affordable with a 45% income tax rate. This would lead to an improvement in income for the majority of the population.[60] Charles M. A. Clark estimates that the United States could support a basic income large enough to eliminate poverty and continue to fund all current government spending (except that which would be made redundant by the basic income) with a flat income tax of 39%.[61]

Tax on consumption (VAT)[edit]

Other taxes[edit]

Other taxes that have been mentioned to finance basic income include tax on capital, carbon tax and financial transaction tax.

Monetary reform[edit]

C.H. Douglas, an early British proponent of basic income and monetary reform.

Major C.H. Douglas argued in the 1920s and 1930s for a political philosophy called Social Credit. Central in this philosophy was a combination of basic income and monetary reform. In the 1990s and onwards, his ideas has been reintroduced by some authors. Among them Michael Rowbotham in The Grip of Death: A Study of Modern Money, Debt Slavery and Destructive Economics (1998)[62] and Richard C. Cook in We Hold These Truths: the Hope of Monetary Reform (2008).

There are also economists and political scientists who have argued for the combination of basic income and monetary reform with inspiration from the original Chicago plan and the 100% money proposals from the 1930s. Among them Joseph Huber and James Robertson.

In the 2010s there have also been proposals about a different kind of "quantitative easing". British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, for example, has talked about a “People’s QE”, in which the Bank of England would channel money directly to the government, which then would use it to stimulate the economy through different projects. Another model was suggested by a group of economists in an article in Financial Times. They proposed that quantitative easing money from ECB should be given directly to citizens of the eurozone countries, instead of to the banks but also instead of giving it to the government. Economist Milton Friedman once called that kind of payments “helicopter money”.[63]

The monetary reformist Ellen Brown thinks the same. In an article named "How to Fund a Universal Basic Income Without Increasing Taxes or Inflation" she notes that if the entire welfare budget were split among the country’s 50 million adults, each of them would get £5,160 a year. That, however, is not enough to cover for basic survival in a modern economy - she says. To pay for the rest one could either increase other taxes and/or reduce other programs, or one could go for "quantitative easing". The main objection to "any form of quantitative easing in which new money gets into the real economy", she explains, is that it would cause hyperinflation. But the quantitative easing in the form of money from central banks to the British economy via the banks, $3.7 trillion according to Brown, has not increased inflation so far. She also thinks that the velocity of money would change with quantitative easing directly to the people, and that this would reduce any tendences to inflation.[64]

Contemporary political parties that include both basic income and monetary reform in their political platform include: New Economics Party (New Zealand)[65] and Enhet(Sweden).

Reduction of medical costs[edit]

The Canadian Medical Association passed a motion in 2015 which clearly signed the organisations support for basic income, and for basic income trials in Canada.[66]

Paul Mason, a British journalist, has stated that universal basic income would probably reduce the high medical costs associated with diseases of poverty. The stress, diseases like high blood pressure, type II diabetes etc. would according to Mason probably become less common.[67]

Taxing the data giants[edit]

The Guardian has speculated and vaguely suggested, in an Editorial published in September 2017, that basic income could be financed by taxing data giants like Google and Facebook. The editorial writes: "Mrs Clinton tried, and failed, to make the numbers work by looking at spectrum levies. But if data is the new oil, why not tax the Googles of this world for the use of customers’ data? These could capitalise a fund that makes annual payouts. Citizens could then see they had collectively traded their privacy for something more tangible than tweets. Tech firms might squeal. But one of the fund’s biggest contributors would be Facebook – its founder, Mark Zuckerberg, backs UBI as an idea. He, and others, could now do so with their cash."[68]

More specific funding proposals[edit]

United States[edit]

Scott Santens, basic income activist[edit]

Scott Santens, an American basic income activist has suggested a yearly basic income of $13,266 ($1,105/mo) per adult citizen and $4,598 ($383/mo) per citizen under 18 in the United States. He proposes among other things the following reforms to achieve this:[69]

Food and nutrition assistance programs ($108 billion) and temporary assistance for needy families ($17 billion) is removed.

Likewise the following are also replaced with basic income: The earned income credit ($73 billion), the child tax credit ($56 billion), home ownership tax expenditures ($340 billion), married filing jointly preferential tax treatment ($70 billion), the tax break on pensions ($160 billion), fossil fuel subsidies ($33 billion), and treating capital gains differently than ordinary income ($160 billion).

A carbon tax starting at $50/ton with annual increases of $15/ton. That would, according to his calculations, add $150 billion to the basic income fund the first year, and thereafter grow annually. In five years it could grow enough to provide everyone with a basic income at about $100 per month.

A financial transaction tax starting at 0.34% (based on a microsimulation by Urban-Brookings). It would raise an estimated $75 billion.

Seigniorage reform, or monetary reform, by which he means public money creation instead of money creation through bank loans. Such a reform could according to Santens annually contribute with about $2.22 trillion to basic income.

Land-value tax (LVT)

Existing basic income and related systems[edit]

Main article: Basic income pilots

See also: Basic income around the world

Omitara, one of the two poor villages in Namibia where a local basic income was tested in 2008–2009.

The Permanent Fund of Alaska in the United States provides a kind of basic income, based on the oil and gas revenues of the state, to (nearly) all state residents. During her 2016 presidential campaign, former U.S. Secretary of StateHillary Clinton, along with her husband, considered including a policy similar to the Alaska Permanent Fund called "Alaska for America" as part of their platform after reading Peter Barnes book on the subject With Liberty and Dividends for All. Ultimately, the Clintons decided not to, with Hillary stating in her 2016 election memoir What Happened, "Unfortunately, we couldn't make the numbers work."[70] However, in retrospect Clinton also said, "I wonder now whether we should have thrown caution to the wind and embraced 'Alaska for America' as a long-term goal and figured out the details later", considering that former Republican U.S. Treasury Secretaries James Baker and Henry Paulson have also proposed a similar nationwide policy.[71][72]

Bolsa Família is a big social welfare program in Brazil that provides money to many poor families in the country. The system is related to basic income, but also has some differences.

There are also several smaller experiments, which have been labeled as "basic income pilots". The best known are:

Experiments with negative income tax in United States and Canada in the 1960s and 1970s.

A town in Manitoba, Canada, experimented with Mincome, a basic guaranteed income in the 1970s.[73]

The Basic Income Grant (BIG) in Namibia, launched in 2008 and ended in 2009.[74]

An independent pilot implemented in São Paulo, Brazil.[75]

Several villages in India participated in basic income trial,[76] while the government has proposed a guaranteed basic income for all citizens.[77]

The GiveDirectly experiment in Nairobi, Kenya, which is the biggest and longest basic income pilot as of 2017.[78]

The city of Utrecht in the Netherlands launched an experiment in early 2017 that is testing different rates of aid.[77]

In Canada, the Ontario provincial government launched a three-year basic income pilot in the cities of Hamilton, Thunder Bay, and Lindsay in July 2017.[79][80] Initial reports indicated difficulties in finding and receiving applications from eligible individuals and households,[81] and as of November 2017, the Ontarian government was still seeking more applicants.[82]

The Finnish government implemented a two-year pilot in January 2017 involving 2,000 subjects.[83]

Eight, a nonprofit organisation, launched a project in a village in Fort Portal, Uganda, in January 2017, providing income for 56 adults and 88 children through mobile money.[84]

Prominent advocates[edit]

Main article: List of advocates of basic income

Petitions, polls and referendums[edit]

2008: an official petition for basic income was started in Germany by Susanne Wiest.[85] The petition was accepted and Susanne Wiest was invited for a hearing at the German parliament's Commission of Petitions. After the hearing, the petition was closed as "unrealizable".[58]

2015: a citizen's initiative in Spain received 185,000 signatures, short of the required amount for the proposal to be discussed in parliament.[86]

2016: The world's first universal basic income referendum in Switzerland on 5 June 2016 was rejected with a 76.9 percent majority.[1][87] Also in 2016 a poll showed that 58 percent of the European people are aware of basic income and 65 percent would vote in favor of the idea.[88]

2017: POLITICO/Morning Consult asked 1994 Americans about their opinions on several political issues. One of the questions were about the respondants attitudes towards a national basic income in the United States. 43 percent either ‘strongly supported’ or ‘somewhat supported’ the idea.[89]

See also[edit]

Automation and the Future of Jobs

Basic income around the world

Basic income pilots

Cash transfers

Citizen's dividend

Economic, social and cultural rights

Equality of outcome

FairTax: Monthly tax rebate

Geolibertarianism

GiveDirectly

Global basic income

Guaranteed minimum income

Involuntary unemployment

Left-libertarianism

List of basic income models

Living wage

Mincome

Minimum wage

Negative income tax

New Cuban Economy

Old Age Security

Quatinga Velho

Post-scarcity economy

Redistribution of income and wealth

Refusal of work

Right to adequate standard of living

Social dividend

Social safety net

Speenhamland system

The Triple Revolution

Unemployment benefits

Universal Credit

Welfare capitalism

Working time

Work–life balance

References[edit]

^ Jump up to:a b "Vorlage Nr. 601 – Vorläufige amtliche Endergebnisse". admin.ch. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

Jump up^ "Improving Social Security in Canada Guaranteed Annual Income: A Supplementary Paper". Government of Canada. 1994. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

Jump up^ "History of Basic Income". Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN). Archived from the original on 21 June 2008.

Jump up^ Universal Basic Income: A Review Social Science Research Network (SSRN). Accessed 6 August 2017.

Jump up^ Mattei, Lauro; Sánchez-Ancochea, Diego (2011). "Bolsa Família, poverty and inequality: Political and economic effects in the short and long run". Global Social Policy: 1. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

Jump up^ History of Basic Income Basic Income Earth Network

Jump up^ Sloman, Peter (2015). Beveridge's rival: Juliet Rhys-Williams and the campaign for basic income, 1942-55 (PDF) (Report). New College, Oxford. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

Jump up^ Fitzpatrick, Tony (1999). Freedom and Security: an introduction to the basic income debate (1. publ. ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-312-22313-7.

Jump up^ "American President: Richard Milhous Nixon: Domestic Affairs". MillerCenter.org. Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

Jump up^ Ronald Blaschke The basic income debate in Germany and some basic reflections(läst 13 December 2012)

Jump up^ Standing, Guy. "How Cash Transfers Promote the Case for Basic Income". Basic Income Studies. 3 (1). doi:10.2202/1932-0183.1106. ISSN 1932-0183.

Jump up^ G Standing, Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen (2017) ch 7. E McGaughey, 'Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy' (2018) SSRN, part 4(2)

Jump up^ "BIEN: frequently asked questions". Basic Income Earth Network. Retrieved 24 July2013.

Jump up^ "Research". Basic Income Earth Network. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

Jump up^ Bregman, Rutger (6 March 2017). "Utopian thinking: the easy way to eradicate poverty – Rutger Bregman" – via www.theguardian.com.

Jump up^ "A Basic Income for All". bostonreview.net. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

Jump up^ "Independence, Propertylessness, and Basic Income - A Theory of Freedom as the Power to Say No - K. Widerquist - Palgrave Macmillan". Retrieved 24 April 2018.

^ Jump up to:a b c Sheahen, Allan. Basic Income Guarantee: Your Right to Economic Security. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. Book. 29 March 2016.

^ Jump up to:a b McKay, Ailsa (2001). "Rethinking Work and Income Maintenance Policy: Promoting Gender Equality Through a Citizens' Basic Income". Feminist Economics. 7 (1): 97–118. doi:10.1080/13545700010022721.

Jump up^ McKay, Ailsa (2005). The Future of Social Security Policy: Women, Work and a Citizens Basic Income. Routledge. ISBN 9781134287185.

Jump up^ Dolan, Ed (27 January 2014). "A Universal Basic Income: Conservative, Progressive, and Libertarian Perspectives". EconoMonitor. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

Jump up^ Weisenthal, Joe (13 May 2013). "There's A Way To Give Everyone In America An Income That Conservatives And Liberals Can Both Love". Business Insider. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

Jump up^ Gordon, Noah (6 August 2014). "The Conservative Case for a Guaranteed Basic Income". The Atlantic. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

Jump up^ Kaori Katada. "Basic Income and Feminism: in terms of "the gender division of labor"" (PDF).

Jump up^ Caitlin McLean (September 2015). "Beyond Care: Expanding the Feminist Debate on Universal Basic Income" (PDF). WiSE.

Jump up^ "urn:nbn:se:su:diva-7385: Just Distribution : Rawlsian Liberalism and the Politics of Basic Income". Diva-portal.org. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

^ Jump up to:a b Gilles Séguin. "Improving Social Security in Canada – Guaranteed Annual Income: A Supplementary Paper, Government of Canada, 1994". Canadiansocialresearch.net. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

Jump up^ The Need for Basic Income: An Interview with Philippe Van Parijs, Imprints, Vol. 1, No. 3 (March 1997). The interview was conducted by Christopher Bertram.

Jump up^ Belik, Vivian (5 September 2011). "A Town Without Poverty? Canada's only experiment in guaranteed income finally gets reckoning". Dominionpaper.ca. Retrieved 16 August2013.

Jump up^ A guaranteed annual income: From Mincome to the millennium (PDF) Derek Hum and Wayne Simpson

Jump up^ "Basic Income Grant Coalition: Pilot Project". BIG Coalition Namibia. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

Jump up^ "Otjivero residents to get bridging allowance as BIG pilot ends". Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

Jump up^ Meade, James Edward. Full Employment Regained?, Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-55697-X

Jump up^ Wolf Chiappella. "Tim Harford — Article — A universal income is not such a silly idea". Tim Harford. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

Jump up^ "Fellows". Adam Smith Institute. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

Jump up^ Worstall, Tim (12 July 2013). "Forbes article". Forbes.

Jump up^ Koga, Kenya. "Pennies From Heaven." Economist 409.8859 (2013): 67–68. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 April 2016.

Jump up^ David K. Evans, Anna Popova (1 May 2014). "Cash Transfers and Temptation Goods: A Review of Global Evidence. Policy Research Working Paper 6886" (PDF). The World Bank. Office of the Chief Economist.: 36. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

Jump up^ Frances Goldin, Debby Smith, Michael Smith (2014). Imagine: Living in a Socialist USA.Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-230557-3 p. 132.

Jump up^ André Gorz, Pour un revenu inconditionnel suffisant, published in Transversales/Science-Culture (n° 3, 3e trimestre 2002) (in French)

Jump up^ Tanner, Michael. "The Pros and Cons of a Guaranteed National Income." Policy Analysis. CATO institute, 12 May 2015, Web. 2, 7 March 2016.

Jump up^ "Basic Income, sustainable consumption and the 'DeGrowth' movement | BIEN". BIEN. 2016-08-13. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

Jump up^ Schneider, Nathan (6 January 2015). "Why the Tech Elite Is Getting Behind Universal Basic Income". Vice.

^ Jump up to:a bhttps://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/ERP_2016_Book_Complete%20JA.pdf whitehouse

Jump up^ Schneider, Nathan (6 January 2015). "Why the Tech Elite Is Getting Behind Universal Basic Income". Vice.

Jump up^ Forget, Evelyn L. (2011). "The Town With No Poverty: The Health Effects of a Canadian Guaranteed Annual Income Field Experiment". Canadian Public Policy. 37 (3): 283–305. doi:10.3138/cpp.37.3.283.

Jump up^ Roy, Abhishek. "Part 2 of SPI's Universal Basic Income Series". Sevenpillarsinstitute.org. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

Jump up^ "Paul Vallee, Basic Income, for publication". Google Docs. Retrieved 2017-05-28.

Jump up^ "Majority of Economists Surveyed Are against the Universal Basic Income". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

Jump up^ "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

Jump up^ Shutt, Harry (15 March 2010). Beyond the Profits System: Possibilities for the Post-Capitalist Era. Zed Books. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-84813-417-1. a flat rate payment as of right to all resident citizens over the school leaving age, irrespective of means of employment status...it would in principle replace all existing social-security entitlements with the exception of child benefits.

Jump up^ Wright, Erik Olin. "Basic Income as a Socialist Project," paper presented at the annual US-BIG Congress, 4 – 6 March 2005 (University of Wisconsin, March 2005).

Jump up^ "Basic Income". Media Hell. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

Jump up^ Russell, Bertrand. Roads to Freedom. Socialism, Anarchism and Syndicalism, London: Unwin Books (1918), pp. 80–81 and 127

Jump up^ Marangos, John (2003). "Social Dividend versus Basic Income Guarantee in Market Socialism". International Journal of Political Economy. 34 (3). JSTOR 40470892.

Jump up^ Standing, Guy. "Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen, London: Penguin (2017) https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/304706/basic-income/. Retrieved 1 April2018. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up^ Standing, Guy. "The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay", London: Bitback (2016) https://www.bitebackpublishing.com/books/the-corruption-of-capitalism. Retrieved 1 April 2018. Missing or empty |title= (help)

^ Jump up to:a b "Deutscher Bundestag – Problematische Auswirkungen auf Arbeitsanreize" (in German). Bundestag.de. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

Jump up^ "Petitionen: Verwendung von Cookies nicht aktiviert" (PDF).

Jump up^ "Basic Income – Why and how in difficult economic times : Financing a BI in Ireland"(PDF). Social Justice Ireland. 14 September 2012.

Jump up^ Clarck, Charles M.A. "PROMOTING ECONOMIC EQUITY IN A 21 st CENTURY ECONOMY: THE BASIC INCOME SOLUTION" (PDF). USBIG.net. USBIG Discussion Paper. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

Jump up^ Matters of life and debt (Review of The Wealth of the World and the Poverty of Nationsby Daniel Cohen and The Grip of Death by Michael Rowbotham). Coates, Barry. The Times Literary Supplement (London, England), Friday, 21 April 2000; pg. 31; Issue 5064. (1495 words)

Jump up^ "Can the ECB create money for a universal basic income?". 15 February 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

Jump up^ Brown, Ellen Ellen Brown: “How to Fund a Universal Basic Income Without Increasing Taxes or Inflation” CommonDreams.org. 2017

Jump up^ Deidre, Kent Combining resource (including land) taxes, monetary reform and basic income is the political challenge of our time

Jump up^ "Opinion - Basic income: just what the doctor ordered". Retrieved 24 April 2018.

Jump up^ Talks at Google (3 March 2016). "Paul Mason: 'PostCapitalism' – Talks at Google". Retrieved 28 July 2016 – via YouTube.

Jump up^ Editorial The Guardian view on universal basic income: tax data giants to pay for itThe Guardian. 15 September 2017.

Jump up^ How Traditional Welfare and Taxes Can Be Reformed to Support Universal Basic Income Futurism.com

Jump up^ Matthews, Dylan (September 12, 2017). "Hillary Clinton almost ran for president on a universal basic income". Vox. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

Jump up^ Clinton, Hillary (September 12, 2017). What Happened. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-1-50117-556-5.

Jump up^ Baker III, James A.; Feldstein, Martin S.; Halstead, Ted; Mankiw, N. Gregory; Paulson Jr., Henry M.; Shultz, George P.; Stephenson, Thomas; Walton, Rob (February 2017). The Conservative Case for Carbon Dividends (PDF) (Report). Climate Leadership Council. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

Jump up^ "Innovation series: Does the gig economy mean 'endless possibilities' or the death of jobs?". 8 October 2016.

Jump up^ Krahe, Dialika. "How a Basic Income Program Saved a Namibian Village". www.spiegel.de/. Spiegel Online. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

Jump up^ "BRAZIL: Basic Income in Quatinga Velho celebrates 3-years of operation | BIEN". Basicincome.org. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

Jump up^ "INDIA: Basic Income Pilot Project Finds Positive Results," Archived 9 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Basic Income News, BIEN (22 September 2012)

^ Jump up to:a b Tognini, Giacomo. "Universal Basic Income, 5 Experiments From Around The World". www.worldcrunch.com. WorldCrunch. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

Jump up^ Mathews, Dylan. "This Kenyan village is a laboratory for the biggest basic income experiment ever". Vox.com. Vox. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

Jump up^ "Ontario Basic Income Pilot". www.ontario.ca.

Jump up^ Monsebraaten, Laurie (April 24, 2017). "Ontario launches basic income pilot for 4,000 in Hamilton, Thunder Bay, Lindsay". Toronto Star. Star Media Group. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

Jump up^ Monsebraaten, Laurie (September 17, 2017). "Handing out money for free harder than it looks". Toronto Star. Star Media Group. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

Jump up^ "Ontario seeks more applicants for basic income pilot". CBC.ca. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. November 25, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

Jump up^ Sodha, Sonia. "Is Finland's basic universal income a solution to automation, fewer jobs and lower wages?". www.theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

Jump up^ eight.world

Jump up^ "Bundestag will Petition zum bedingungslosen Grundeinkommen ohne Diskussion abschließen › Piratenpartei Deutschland". Piratenpartei.de. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

Jump up^ "Spanish Popular initiative for basic income collects 185.000 signatures". Basicincome.org. 10 October 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

Jump up^ Ben Schiller 02.05.16 7:00 AM (5 February 2016). "Switzerland Will Hold The World's First Universal Basic Income Referendum | Co.Exist | ideas + impact". Fastcoexist.com. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

Jump up^ "EU Survey: 64% of Europeans in Favour of Basic Income". Basicincome.org. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

Jump up^ "US: New POLITICO/Morning Consult poll finds that 43% of Americans are in favour of a UBI - Basic Income News". 5 October 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

Further reading[edit]

Colombino, U. (2015). "Five Crossroads on the Way to Basic Income: An Italian Tour". Italian Economic Journal. 1 (3): 353–389. doi:10.1007/s40797-015-0018-3.

Benjamin M. Friedman, "Born to Be Free" (review of Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght, Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy, Harvard University Press, 2017), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIV, no. 15 (12 October 2017), pp. 39–41.

Marinescu, Ioana (February 2018). "No Strings Attached: The Behavioral Effects of U.S. Unconditional Cash Transfer Programs". NBER Working Paper No. 24337. doi:10.3386/w24337.

E McGaughey, 'Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy' (2018) SSRN, part 4(2)

Karl Widerquist, Jose Noguera, Yannick Vanderborght, and Jurgen De Wispelaere (editors). Basic Income: An Anthology of Contemporary Research, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013

Widerquist, Karl (ed.). Exploring the Basic Income Guarantee, (book series). Palgrave Macmillan.

Karl Widerquist. Independence, Propertylessness, and Basic Income: A Theory of Freedom as the Power to Say No, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, March 2013. Early drafts of each chapter are available online for free at this link.

Ailsa McKay. The Future of Social Security Policy: Women, Work and a Citizens Basic Income, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 9781134287185.