Wake therapy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Sleep Deprivation Therapy is in the process of being merged into this article. If possible, please edit only this article, as the article mentioned above may be turned into a redirect. Relevant discussion may be found here. (April 2023) |

Wake therapy is a specific application of intentional sleep deprivation. It encompasses many sleep-restricting paradigms that aim to address mood disorders with a form of non-pharmacological therapy.[1]

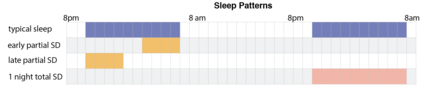

Wake therapy was first popularized in 1966 and 1971 following articles by Schulte and by Pflug and Tölle describing striking symptom relief in depressed individuals after 1 night of total sleep deprivation. Wake therapy can involve partial sleep deprivation, which usually consists of restricting sleep to 4–6 hours, or total sleep deprivation, in which an individual stays up for more than 24 consecutive hours. During total sleep deprivation, an individual typically stays up about 36 hours, spanning a normal awakening time until the evening after the deprivation. It can also involve shifting the sleep schedule to be later or earlier than a typical schedule (eg. going to bed at 5 am), which is called Sleep Phase Advancement. Older studies involved the repetition of sleep deprivation in the treatment of depression, either until the person showed a response to the treatment or until the person had reached a threshold for the possible number of sleep deprivation treatments.

Chronic sleep deprivation is dangerous and in modern research studies it is no longer common to repeat sleep deprivation treatments close together in time.[2]

Recent closed-loop paradigms have been developed to selectively deprive individuals of some stages—but not others—of sleep. During slow-wave sleep deprivation, researchers monitor the electrical activity on an individual's scalp with electroencephalography (EEG) in real-time, and use sensory stimulation (eg. playing a noise such as a burst of pink noise) to disrupt that stage of sleep (eg. to interfere with slow waves during non-rapid eye movement sleep) The goal of these paradigms is to investigate how the deprivation of one type of sleep stage, or sleep microarchitecture, affects outcome measures, rather than the deprivation of all sleep stages. One drawback of closed loop sleep deprivation paradigms is that they must be carefully calibrated for each individual. If researchers use auditory stimuli to inhibit slow waves, they must calibrate the volume of the stimulus so that it is loud enough to evoke a sensory response, but quiet enough that it does not wake the patient from sleep. There is some evidence that depriving individuals of slow wave sleep can induce a rapid antidepressant effect in a dose-dependent manner, meaning a greater reduction in slow wave activity relative to baseline is expected to induce greater symptom relief.[1]

Response rate[edit]

The response rate to sleep deprivation is generally agreed to be approximately 50%. A 2017 meta-analysis of 66 sleep studies with partial or total sleep deprivation in the treatment of depression found that the overall response rate (immediate relief of symptoms) to total sleep deprivation was 50.4% of individuals, and the response rate to partial sleep deprivation was 53.1%[3] In 2009, a separate review on sleep deprivation found that 1700 patients with depression across 75 separate studies showed a response rate that ranged from 40 - 60%.[4] For reference, the non-response rate for conventional antidepressant pharmacotherapy is estimated to be ~30%, but symptom relief may be delayed by several weeks after the onset of treatment (compared to the immediate, transient relief induced by sleep deprivation).[5] Metrics of mood change vary highly across studies, including surveys of daily mood, or clinician administered interviews that assess the severity of depression symptoms. One benefit to sleep deprivation is that it can provide relief from symptoms within 6–12 hours after sleep deprivation, a rapid effect compared to the 4–6 weeks that it may take conventional treatments to have an effect.[6]

One downside of sleep deprivation therapy is that the beneficial effects are transient, and disappear after even short periods of sleep.[7][6] Even ultra-short periods of sleep lasting seconds, termed microsleeps, have been shown to cause a relapse in symptoms.[8]

Relapse after recovery sleep[edit]

One meta-analysis of over 1700 unmedicated depressed patients who had undergone sleep deprivation found that 83% relapsed in their symptoms after one night of recovery sleep.[9] Only 5-10 % of patients who initially respond to sleep deprivation show sustained remission.[4] However, when sleep deprivation is combined with pharmacological treatments, the number of patients who show sustained remission is much higher, with rates as high as half of patients experiencing sustained remission.[4] Compared to a relapse rate of 83% for unmedicated patients, patients who simultaneously took antidepressants only experienced a relapse rate of 59% after a night of recovery sleep.[9]

Effect of sleep deprivation depends on psychiatric status[edit]

The effect of sleep deprivation on mood is dependent on an individual's psychiatric status. Healthy individuals with no history of mood disorders who undergo sleep deprivation often show no change or a worsening of mood after the sleep deprivation.[4] In addition to constant or worsening mood, they also show an increase in tiredness, agitation, and restlessness.[8] Similarly, individuals with psychiatric disorders such as obsessive compulsive disorder or those who suffer from panic attacks do not show reliable improvements in mood disorder.[4]

| Type | Average Response Rate* | Average Response Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Partial sleep deprivation (~ 4–6 hours of sleep in either the first or last half of the night) | ~ 53.1%[3] | ~ 1 Day [10] |

| Total sleep deprivation (no sleep 24–46 hours) | ~40-60 %[4] | ~ 1 Day[10] |

| Scale Name | Date Published | Summary | Inter-rater reliability | Time to complete | Typical reduction rate required for "remission" |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale[11] | 1960 | 21 items | 0.46 to 0.97[12] | 15–20 minutes | 30 - 40% reduction in baseline score, or a score <7 |

| Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale[13] | 1978 | 10 items: 9 based on patient report, 1 rater's observation | 0.89-0.97[14] | 15–20 minutes | score < 5 |

Side effects[edit]

The only known contraindication to sleep deprivation therapy for individuals with unipolar depression is a risk of seizures. Some studies have shown that the stress associated with a night of sleep deprivation can precipitate unexpected medical conditions, such as a heart attack.[15] Other known side effects of sleep deprivation include general fatigue, and headaches.[8] For individuals with bipolar depression, sleep deprivation can sometimes cause a switch into a manic state.[16]

Combination of antidepressant pharmacological intervention and total sleep deprivation[edit]

Unipolar depression[edit]

Although individual studies have shown a positive effect of combined antidepressant-sleep deprivation therapy, there is currently no widely-accepted consensus about whether combined treatment is superior to pharmacological intervention alone for individuals with unipolar depression.[17] A meta analysis (2020) of more than 368 patients found that sleep deprivation combined with standard treatment did not reduce depressive symptoms compared to standard treatment alone.[17]

Bipolar depression[edit]

In contrast with unipolar depression, there is a wide body of evidence that sleep deprivation may be useful in the treatment of bipolar depression. A meta analysis of 90 articles found that combining total sleep deprivation and pharmacological intervention significantly increased the antidepressant effects in patient with bipolar depression when compared to pharmacological intervention alone.[18] The metric that the studies used to assess success of the interventions was a depression symptom scale called the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale[13] or the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,[11] which both are used to measure someone's mood. Multiple studies have shown that adding a mood stabilizing medication (lithium, amineptine, or pindolol) to total sleep deprivation can induce a significant decrease in depression symptoms that is sustained at least 10 days after the treatment.[18] When considering the long-term effects of the combined total sleep deprivation-pharmacological intervention, it appears that combination therapy can also improve the maintenance of the antidepressant effect for individuals with bipolar mood disorders. These results suggest that adding total sleep deprivation to bipolar depression pharmacological treatment may result in an augmented treatment response.[18]

Total sleep deprivation may not be necessary to achieve the beneficial effect of combined sleep deprivation-antidepressant therapy- partial sleep deprivation may be sufficient. Compliance in these studies is typically measured with actigraphy in order to track movements and time in bed.

Mechanism[edit]

The mechanism by which sleep deprivation enhances the effect of antidepressant pharmacological intervention is still under investigation. One hypothesis is that sleep deprivation could enhance the effects of the antidepressant drugs, or it could shorten the delay of the drugs effects, which can take up to several months depending on the drug.[19]

BDNF hypothesis[edit]

One hypothesis for the mechanism of sleep deprivation is that it induces a rapid increase in the level of a neutrophic protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which mimics the long term effects of some antidepressant drugs.[20] Drug-naive patients with depression typically show lower levels of BDNF than age and sex-matched controls.[21] An increase in BDNF in patients with depression who take a class of drugs called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors has been reported in several studies to increase after 8 weeks.[21] Similarly, an increase in serum BDNF level is also observed in patients who undergo a single night of total or REM sleep deprivation, however the effect is observed immediately rather than after a long period of time.[20] This increase is hypothesized to be the result of a compensatory mechanism in the brain that produces BDNF to preserve cognitive functions like working memory and attention.[20]

Serotonin hypothesis[edit]

Another hypothesis for the mechanism of sleep deprivation is that it may affect the serotoninergic (5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT]) system, including a receptor called the 5-HT1A receptor.[8] Animals models of sleep deprivation suggest that sleep deprivation increases serotonin neurotransmission in several ways, including 1) increasing extracellular serotonin, 2) increasing serotonin turnover, 3) reducing the sensitivity of serotonin inhibitory autoreceptors and 4) increasing behavioral responsiveness to serotonin precursors.[22] Studies in humans that measure pre-sleep deprivation levels of serotonin with single photon emission computer tomography have provided evidence that responders to sleep deprivation may have a specific deficit in serotoninergic systems.[23]

Barriers to sleep deprivation-antidepressant combination therapy research[edit]

One barrier to understanding the effects of sleep deprivation is the lack of a consistent metric of "response". Although there are standard mood surveys and clinician-rated scales, different investigators use different criterion as evidence of response to the treatment. For example, some investigators have required a 30% decrease in the Hamilton Rating Scale, while others required a 50% decrease.[19]

Other barriers include the fact that researchers are not blind to patient condition when they rate the patient's mood, and that many previous studies have not included control groups, but rather only published findings on patient groups without any control reference.

Skeptics of sleep deprivation therapy argue that it is not the sleep deprivation itself, but rather the prolonged contact with other humans and unusual circumstances of the sleep deprivation that lead to improvements in mood symptoms.[4]

Another major barrier is that depression is a highly heterogenous disorder, spanning both unipolar and bipolar types.[24]

Predictors of antidepressant response to sleep deprivation therapy[edit]

Diurnal Mood[edit]

Mood fluctuations are currently thought to be dependent on circadian processes. A typical healthy individual without a mood disorder shows circadian-locked fluctuations in mood, with positive mood beginning right after the morning awakening, and decaying as the day goes on during prolonged wakefulness. A typical individual with depression will show the opposite mood fluctuation cycle, with a low mood right after morning awakening, which gradually becomes more positive with prolonged wakefulness. These circadian-locked changes across the day are referred to as "diurnal" variations in mood. Evidence across many sleep deprivation studies suggests that an individual's diurnal mood fluctuations can be used to predict whether they will respond to sleep deprivation therapy.[25] Individuals with depression who show the typical low morning mood that increases throughout the day are more likely to respond positively to sleep deprivation than individuals who show mood fluctuations that deviate from the typical pattern.[25] One caveat to these findings is that a single individual may show diurnal fluctuations that vary day-to-day, showing typical diurnal changes on one day while not showing any changes (constant mood) on the next. This complexity was addressed in studies that followed single individuals and administered repeated sleep deprivation on days when the individual showed different mood fluctuations. The studies showed that an individual's ability to show the typical mood fluctuations was a better predictor of whether they would respond to sleep deprivation treatment than the individual's mood state on the particular day that they underwent sleep deprivation.[25]

Short REM latency[edit]

Responsiveness to sleep deprivation is also currently believed to be dependent on observable pattern in a person's regular sleep cycle, such as how quickly a person enters into a sleep cycle called rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.[26] Individuals with depression typically show abnormally short REM sleep onsets, meaning they enter into the REM sleep stage earlier in the course of the night than matched healthy controls. Individuals with depression who have short-latency REM sleep typically respond to sleep deprivation therapy more often than individuals with depression who do not show the typical short latency REM sleep pattern.[26]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Minkel, Jared D.; Krystal, Andrew D.; Benca, Ruth M. (2017-01-01), Kryger, Meir; Roth, Thomas; Dement, William C. (eds.), "Chapter 137 – Unipolar Major Depression", Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine (Sixth Edition), Elsevier, pp. 1352–1362.e5, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-24288-2.00137-9, ISBN 978-0-323-24288-2, retrieved 2020-12-11

- ^ McEwen, Bruce S. (2006). "Sleep deprivation as a neurobiologic and physiologic stressor: allostasis and allostatic load". Metabolism. 55 (10 Suppl 2): S20–S23. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2006.07.008. PMID 16979422.

- ^ a b Boland, Elaine M.; Rao, Hengyi; Dinges, David F.; Smith, Rachel V.; Goel, Namni; Detre, John A.; Basner, Mathias; Sheline, Yvette I.; Thase, Michael E.; Gehrman, Philip R. (2017). "Meta-Analysis of the Antidepressant Effects of Acute Sleep Deprivation". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 78 (8): e1020–e1034. doi:10.4088/JCP.16r11332. ISSN 1555-2101. PMID 28937707.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smeraldi, Francesco Benedetti and Enrico (2009-07-31). "Neuroimaging and Genetics of Antidepressant Response to Sleep Deprivation: Implications for Drug Development". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 15 (22): 2637–2649. doi:10.2174/138161209788957447. PMID 19689334. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ Baghai, Thomas C.; Rupprecht, Hans-Jurgen Moller and Rainer (2006-01-31). "Recent Progress in Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Treatment Options of Major Depression". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 12 (4): 503–515. doi:10.2174/138161206775474422. PMID 16472142. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ a b Oliwenstein, Lori (2006-04-01). "Lifting Moods by Losing Sleep: An Adjunct Therapy for Treating Depression". Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 12 (2): 66–70. doi:10.1089/act.2006.12.66. ISSN 1076-2809.

- ^ Wu, J. C.; Bunney, W. E. (1990-01-01). "The biological basis of an antidepressant response to sleep deprivation and relapse: review and hypothesis". American Journal of Psychiatry. 147 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1176/ajp.147.1.14. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 2403471.

- ^ a b c d Hemmeter, Ulrich-Michael; Hemmeter-Spernal, Julia; Krieg, Jürgen-Christian (2010). "Sleep deprivation in depression". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 10 (7): 1101–1115. doi:10.1586/ern.10.83. ISSN 1473-7175. PMID 20586691. S2CID 18064870.

- ^ a b Wu, J. C.; Bunney, W. E. (1990-01-01). "The biological basis of an antidepressant response to sleep deprivation and relapse: review and hypothesis". American Journal of Psychiatry. 147 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1176/ajp.147.1.14. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 2403471.

- ^ a b Wirz-Justice, Anna; Benedetti, Francesco; Berger, Mathias; Lam, Raymond W.; Martiny, Klaus; Terman, Michael; Wu, Joseph C. (2005). "Chronotherapeutics (light and wake therapy) in affective disorders". Psychological Medicine. 35 (7): 939–944. doi:10.1017/S003329170500437X. ISSN 1469-8978. PMID 16045060.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Max (1960-02-01). "A Rating Scale for Depression". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 23 (1): 56–62. doi:10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 495331. PMID 14399272.

- ^ Bagby, R. Michael; Ryder, Andrew G.; Schuller, Deborah R.; Marshall, Margarita B. (2004-12-01). "The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the Gold Standard Become a Lead Weight?". American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (12): 2163–2177. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2163. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 15569884.

- ^ a b Williams, Janet B. W.; Kobak, Kenneth A. (2008). "Development and reliability of a structured interview guide for the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (SIGMA)". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 192 (1): 52–58. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032532. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 18174510.

- ^ Sajatovic, Martha; Chen, Peijun; Young, Robert C. (2015-01-01), Tohen, Mauricio; Bowden, Charles L.; Nierenberg, Andrew A.; Geddes, John R. (eds.), "Chapter Nine - Rating Scales in Bipolar Disorder", Clinical Trial Design Challenges in Mood Disorders, San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 105–136, ISBN 978-0-12-405170-6, retrieved 2020-11-30

- ^ Delva NJ, Woo M, Southmayd SE, Hawken ER. Myocardial infarction during sleep deprivation in a patient with dextrocardia - a case report. Anglology 52, 83-86 (2001).

- ^ Gold, Alexandra K.; Sylvia, Louisa G. (2016-06-29). "The role of sleep in bipolar disorder". Nature and Science of Sleep. 8: 207–214. doi:10.2147/nss.s85754. PMC 4935164. PMID 27418862.

- ^ a b Ioannou, Michael; Wartenberg, Constanze; Greenbrook, Josephine T.V.; Larson, Tomas; Magnusson, Kajsa; Schmitz, Linnea; Sjögren, Petteri; Stadig, Ida; Szabó, Zoltán; Steingrimsson, Steinn (2020-11-03). "Sleep deprivation as treatment for depression: systematic review and meta‐analysis". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 143 (1): 22–35. doi:10.1111/acps.13253. ISSN 0001-690X. PMC 7839702. PMID 33145770.

- ^ a b c Ramirez-Mahaluf, Juan P.; Rozas-Serri, Enzo; Ivanovic-Zuvic, Fernando; Risco, Luis; Vöhringer, Paul A. (2020). "Effectiveness of Sleep Deprivation in Treating Acute Bipolar Depression as Augmentation Strategy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 70. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00070. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 7052359. PMID 32161557.

- ^ a b Leibenluft, E.; Wehr, T. A. (1992-02-01). "Is sleep deprivation useful in the treatment of depression?". American Journal of Psychiatry. 149 (2): 159–168. doi:10.1176/ajp.149.2.159. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 1734735.

- ^ a b c Rahmani, Maryam; Rahmani, Farzaneh; Rezaei, Nima (2020-02-01). "The Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: Missing Link Between Sleep Deprivation, Insomnia, and Depression". Neurochemical Research. 45 (2): 221–231. doi:10.1007/s11064-019-02914-1. ISSN 1573-6903. PMID 31782101. S2CID 208330722.

- ^ a b Lee, Bun-Hee; Kim, Yong-Ku (2010). "The Roles of BDNF in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression and in Antidepressant Treatment". Psychiatry Investigation. 7 (4): 231–235. doi:10.4306/pi.2010.7.4.231. ISSN 1738-3684. PMC 3022308. PMID 21253405.

- ^ Benedetti, Francesco (2012). "Antidepressant chronotherapeutics for bipolar depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 14 (4): 401–411. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.4/fbenedetti. PMC 3553570. PMID 23393416.

- ^ Peterson, Michael J.; Benca, Ruth M. (2011-01-01), Kryger, Meir H.; Roth, Thomas; Dement, William C. (eds.), "Chapter 130 - Mood Disorders", Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine (Fifth Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 1488–1500, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-6645-3.00130-4, ISBN 978-1-4160-6645-3, retrieved 2020-12-12

- ^ Flint, Jonathan; Kendler, Kenneth S. (2014). "The Genetics of Major Depression". Neuron. 81 (3): 484–503. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.027. PMC 3919201. PMID 24507187.

- ^ a b c Wirz-Justice, Anna (2008). "Diurnal variation of depressive symptoms". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 10 (3): 337–343. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.3/awjustice. ISSN 1294-8322. PMC 3181887. PMID 18979947.

- ^ a b Berger, M.; Calker, D. Van; Riemann, D. (2003). "Sleep and manipulations of the sleep–wake rhythm in depression". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 108 (s418): 83–91. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.17.x. ISSN 1600-0447. PMID 12956821. S2CID 23918249.

Sources[edit]

- Kragh, M.; Martiny, K.; Videbech, P.; Møller, D. N.; Wihlborg, C. S.; Lindhardt, T.; Larsen, E. R. (December 2017). "Wake and light therapy for moderate-to-severe depression - a randomized controlled trial". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 136 (6): 559–570. doi:10.1111/acps.12741. PMID 28422269. S2CID 46869059.

- Boland et al 2019, "Meta-Analysis of the Antidepressant Effects of Acute Sleep Deprivation"

출처 : 프리 백과사전 『위키피디아(Wikipedia)』

단면요법이란 우울증 환자가 야간에 잠들지 않음으로써 우울증세가 급속히 개선된다는 치료법이다.

역사

1971년 독일의 Pflug과 Tolle이 우울증 환자를 하룻밤 잠들게 함으로써 밤샘 직후부터 우울증세가 극적으로 개선됨을 보고하였다[1].그 이후 구미를 중심으로 단면요법이 폭넓게 이루어져 그 높은 유효성이 확인되고 있다.단면요법에 대한 연구는 독일 이탈리아 스위스 등 유럽 국가에서 특히 이뤄져 왔다.

단면 요법의 종류

첫 보고 이후 야간에 전혀 잠들지 않는다는 '전단면'이 기본이었다.이후 정상적인 시간에 입면해 새벽 2시께 각성시켜 깨어있다는 '야간 후반 부분 단면'이 이뤄지는 일도 잦아졌다.야간 중간부터 잠을 자는 '야간 전반 부분 단면'도 이뤄질 수 있다.'전단면'과 '야간 후반 부분단면'은 효과가 동등하다는 보고도 있지만 '야간 후반 부분단면'이 다소 떨어진다는 보고가 많다.야간 전반 부분 단면은 그보다 효과가 떨어지는 것으로 여겨진다.

단면 요법의 적응

「우울증」과「조울증의 우울상」에 대한 효과가 실증되었다[2]. 특히 약물 치료에 대한 효과가 부족하고 우울 상태가 오래 지속되고 있는 경우에 시행된다.신경증으로 인한 우울증 상태에서는 효과를 크게 기대하기 어렵다.공황장애나 간질을 합병하고 있다면 단면으로 공황발작이나 간질발작이 유발될 위험이 있으므로 시행하지 말아야 한다.

단면 요법의 특징

항우울제에 의한 약물치료는 효과가 나타나기까지 2주 이상 걸리는 반면 단면요법은 단면 직후부터 항우울 효과가 나타난다.심한 우울증에서 극적으로 개선되는 경우도 많다.다만 효과가 오래 지속되지 않는 경우가 많아 단면요법 후 수면을 취하면 우울증세가 재연될 수 있다.

병용 요법

단면요법의 효과를 오래 지속시키기 위해 항우울제 등을 통한 약물요법, 조도광요법, 수면시간대를 늦추는 방법 등을 병용하면 좋다.

관련 항목

철야

우울증

조울증(양극성 장애)

광요법(고조도광요법)

각주

^ ^ Pflug B and Tolle R : Disturbance of the 24-hour rhythm in endogenous depression and the treatment of endogenous depression by sleep deprivation. Int Pharmacopsychiatry 1971 ; 6 : 187-196.

^ 수면의료 제2권 제1호 2007 특집 우울과 수면을 둘러싸고 '8. 우울증의 시간생물학적 치료' (주)라이프사이언스

참고 문헌

정신과 치료학 Vol.17 증간호 기분장애 가이드라인 「제5장 치료법의 해설 단면요법」2002년 10월 세이와 서점

수면의료 제2권 제1호 2007 특집 우울과 수면을 둘러싸고 '8. 우울증의 시간생물학적 치료' (주)라이프사이언스

외부 링크

단면요법을 통한 우울증 치료

카테고리: 정신과 치료 기분 장애 수면

최종 갱신 2020년 10월 26일 (월) 01:04 (일시는 개인 설정으로 미설정이면 UTC).

텍스트는 크리에이티브 커먼즈 표시 - 상속 라이센스 하에서 이용 가능합니다.추가 조건이 적용될 수 있습니다.자세한 내용은 이용 약관을 참조하십시오.