2021/12/19

손민석 장신기 선생의[성공한 대통령 김대중과 현대사]를 읽는데

Kang-nam 코로나 이후의 한국 종교

2021/12/17

Gertrude More - Wikipedia 영원읯 철학

Gertrude More

Dame Gertrude More (born as Helen More; 25 March 1606 - 17 August 1633) was a nun of the English Benedictine Congregation, a writer and chief founder of the abbey at Cambrai which became Stanbrook Abbey.

Life[edit]

More was born in Low Leyton in Essex. Her father, Cresacre More, was great-grandson of Thomas More;[1] her mother, Elizabeth Gage, was sister of Sir John Gage, 1st Baronet of Firle, Sussex, Lord Chamberlain to Queen Mary.[2] Her mother died in 1611 and Helen's father, who had trained to be a monk,[3] became responsible for her care and education. Dom Benet Jones, a Benedictine monk, encouraged her to join his projected religious foundation, Our Lady of Comfort, in Cambrai. She was the first of nine postulants admitted to the order on 31 December 1623. Helen More came under the prescriptive influence of the Dominican Augustine Baker and took the religious name of Gertrude.[1] Catherine Gascoigne, one of her peers, was chosen ahead of her by the authorities in Rome as abbess in 1629 because she was older.[2] Gascoigne was more welcoming of Baker's advice. Sister More opposed Baker's approach but eventually gave into his ways - which included writing good books.[1]

Her writing was heavily influenced by the christian mystics such as Julian of Norwich and Teresa of Avila and other spiritual writers[4] and she contributed to the effort to publish their work.[5][6]

The row at Cumbrai continued and Baker was recalled to Douai. Before the row was settled Gertrude died at Cambrai, from smallpox, aged 27.[1]

Posthumous[edit]

Some papers found after her death and arranged by Father Baker, were afterwards published in two separate works: one entitled The Holy Practices of a Divine Lover, or the Sainctly Ideot's Devotions (Paris, 1657); the other, Confessiones Amantis, or Spiritual Exercises, or Ideot's Devotions, to which was prefixed her Apology, for herself and for her spiritual guide (Paris, 1658).

The Perennial Philosophy: Review — The Contemplative Life. - Mortification, Non-Attachment, Right Livelihood

The Perennial Tradition and Comparative Mysticism

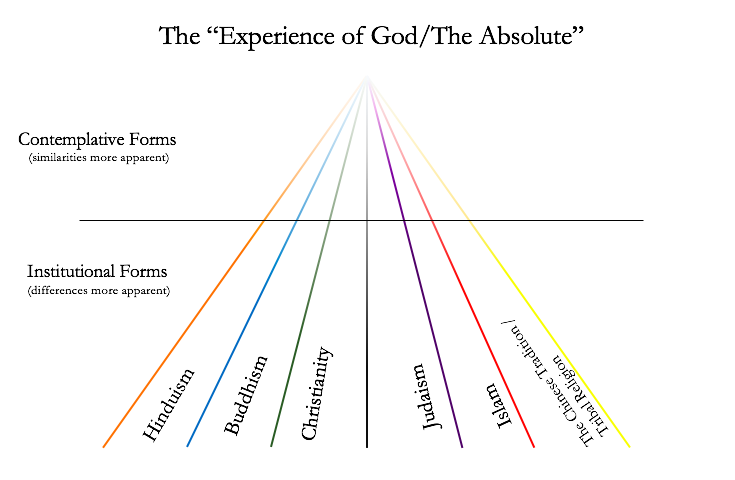

Mystic or contemplative strands of the world's religious traditions are sometimes grouped together and categorized in what has been called "The Perennial Tradition." The term perennial refers to the fact that the ideas associated with these contemplative versions of faith continue to arise, and show themselves throughout history, independent of religious tradition. On this theory, the perennial contemplative tradition is embedded within each individual religion – it is the "common denominator" among the diversity of religious thought.

The most famous treatment of the Perennial Tradition comes from Aldous Huxley. In his The Perennial Philosophy he defines the concept as follows:

"Philosophia Perennis: the phrase was coined by Leibniz; but the thing — the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man's final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being — the thing is immemorial and universal."

Or, put in more simplified terms:

One of the primary debates surrounding the Perennial Tradition is just how unified world mysticism actually is.

[영어 속어] (사람 종류로서의) Asshole 애스홀 - 10 Characteristics Of An Asshole

====

10 Defining Characteristics of an asshole that never go wrong

Namgok Lee 논어 첫 장에 대한 단상 하나 더하기.

2021/12/16

Misinformation Has Already Made Its Way to Facebook's Metaverse - Bloomberg

Misinformation Has Already Made Its Way to the Metaverse

Virtual worlds will be even harder to police than social mediaBy

Jillian Deutsch,

Naomi Nix, and

Sarah Kopit

December 16, 2021, 12:30 AM GMT+10:30

Sensorium’s AI bot David Source: Sensorium Corp.

Sensorium’s AI bot David Source: Sensorium Corp. ===

In their version of the metaverse, creators of the startup Sensorium Corp. envision a fun-filled environment where your likeness can take a virtual tour of an abandoned undersea world, watch a livestreamed concert with French DJ Jean-Michel Jarre or chat with bots, such as leather-jacket-clad Kate, who enjoys white wine with her friends.

But at a demo of this virtual world at a tech conference in Lisbon earlier this year, things got weird. While attendees chatted with these virtual personas, some were introduced to a bald-headed bot named David who, when simply asked what he thought of vaccines, began spewing health misinformation. Vaccines, he claimed in one demo, are sometimes more dangerous than the diseases they try to prevent.

After their creation’s embarrassing display, David’s developers at Sensorium said they plan to add filters to limit what he can say about sensitive topics. But the moment illustrated how easy it might be for people to encounter offensive or misleading content in the metaverse—and how difficult it will be to control it.

Companies including Apple Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Facebook parent Meta Platforms Inc. are racing to build out the metaverse, an immersive digital world that evangelists say will eventually replace some in-person interactions. The technology is in its infancy, but industry watchers are raising alarms about whether the nightmarish content moderation challenges already plaguing social media could be even worse in these new virtual- and augmented reality-powered worlds.

Tech companies’ mostly dismal track record on policing offensive content has come under renewed scrutiny in recent months following the release of a cache of thousands of Meta’s internal documents to U.S. regulators by former Facebook product manager Frances Haugen. The documents, which were provided to Congress and obtained by news organizations in redacted form, surfaced new details about how Meta’s algorithms spread harmful information such as conspiracy theories, hateful language and violence, and led to dozens of critical stories by the Wall Street Journal and a consortium of news organizations. The reports naturally prompted questions about how Meta and others intend to patrol the burgeoning virtual world for offensive behavior and misleading material.

“Despite the name change, Meta still allows purveyors of dangerous misinformation to thrive on its existing apps,” said Alex Cadier, managing director of NewsGuard in the U.K. “If the company hasn’t been able to effectively tackle misinformation on more simple platforms like Facebook and Instagram, it seems unlikely they’ll be able to do so in the much more complex metaverse.”

Read more: The Facebook Papers provide rare insight into the ways the company created a social media behemoth

Meta executives haven’t been ignorant of the criticism. As they build up hype about the metaverse, they’ve pledged to take into account the privacy and well-being of their users as they develop the platform. The company also argues that these next-generation virtual worlds won’t be owned exclusively by Meta, but will come from a collection of engineers, creators and tech companies whose environments and products work together.

Those innovators, and regulators around the world, can start now to debate policies that would maintain the safety of the metaverse even before the underlying technology has been fully developed, executives say.

“In the past, the speed at which new technologies arrived sometimes left policy makers and regulators playing catch-up,” said Nick Clegg, vice president of global affairs, in October at Meta’s annual Connect conference. “It doesn’t have to be the case this time around because we have years before the metaverse we envision is fully realized.”

Meta also says it plans to work with human rights groups and government experts to responsibly develop the virtual world, and it’s investing $50 million to that end.

Sci-Fi Becomes Real

To its evangelists, virtual and augmented reality will unlock the ability to experience the world in ways that previously existed only in the dreams of sci-fi novelists. Companies will be able to hold meetings in digital boardrooms, where employees in disparate locations can feel as if they are really together in one place. Friends will choose their own avatars and teleport together into concerts, exercise classes and 3D video games. Artists will be able to host creative experiences tailored to geographic locations in augmented reality, for any device holder to enjoy. Entrepreneurs will create virtual stores where digital and physical goods could be purchased.

But digital watchdogs say the same qualities that make the metaverse a tantalizing innovation may also open the door even wider to harmful content. The realistic feeling of virtual reality-powered experiences could be a dangerous weapon in the hands of bad actors seeking to stoke hate, violence and terrorism.

“The Facebook Papers showed that the platform can function almost like a turn-key system for extremist recruiters and the metaverse would make it even easier to perpetrate that violence,” said Karen Kornbluh, director of the German Marshall Fund’s Digital Innovation and Democracy Initiative and former U.S. ambassador to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Read More: It’s awkward being a woman in the metaverse

Though the far-reaching, interconnected metaverse is still theoretical, existing virtual reality and gaming platforms offer a window into what kinds of problematic content could flourish there.

The Facebook Papers revealed that the company already has evidence that offensive content is likely to make the jump from social to virtual. In one example, a Facebook employee describes experiencing a brush of racism while playing the virtual reality game Rec Room on an Oculus Quest headset.

After entering one of the most popular virtual worlds in the game, the staffer was greeted with “continuous chants of: ‘N***** N***** N*****.’” According to the documents, the employee wrote in an internal discussion forum that he or she tried to figure out who was yelling and how to report them, but couldn’t. Rec Room said it provides several controls to identify speakers even when that person isn’t visible, and in this case it banned the offending user's account.

“I eventually gave up and left the world feeling defeated,” wrote the employee, whose name was redacted in the documents.

Bad VR Behavior

The abuse has also already reached other VR products. People on VRChat, a platform where users can explore worlds dressed as different avatars, describe an almost transformative experience where they’ve built a virtual community unparalleled in the real world. On a Reddit thread about VRChat, they also describe nearly unbearable amounts of racism, homophobia, transphobia—and “don’t forget the dumb Nazis,” as one VRChat user wrote. It’s not uncommon for players to walk around repeating the N-word, while some virtual worlds get raided by Hitler and KKK avatars.

VRChat wrote in 2018 that it was working to address the “percentage of users that choose to engage in disrespectful or harmful behavior” with a moderation team that “monitors VRChat constantly.” But, years later, players are still reporting harmful users, and say that “nothing is seemingly ever done.” Others try muting or blocking problematic users’ voices or avatars, but the frequency of abuse can be overwhelming.

People also describe racism on popular video games like Second Life and Fortnite; some women have described being sexually harassed or assaulted on virtual reality platforms; and parents have raised concerns that their children were being groomed on the seemingly innocuous Roblox gaming platform for kids.

Social media companies like Meta, Twitter Inc. and Google’s YouTube have detailed policies that prohibit users from spreading offensive or dangerous content. To moderate their networks, most lean heavily on artificial intelligence systems to scan for images, text and videos that look like they could violate rules against hate speech or inciting violence. Sometimes those systems automatically remove the offensive posts. Other times the platforms apply special labels to the content or limit its visibility.

The degree to which the metaverse remains a safe space will depend partially on how companies train their AI systems to moderate the platforms, said Andrea-Emilio Rizzoli, the director of Switzerland’s Dalle Molle Institute for Artificial Intelligence. AI can be trained to detect and take down hate speech and misinformation, and systems can also inadvertently amplify it.

The level of problematic content in the metaverse will also depend on whether tech companies design digital environments to function like small invitation-only private groups or wide-open public squares. Whistle-blower Haugen has been openly critical of Facebook’s metaverse plans, but recently told European lawmakers that hate speech and misinformation in virtual worlds might not travel as far or as quickly as it does on social media, because most people would be interacting in small numbers.

But it’s also just as likely that Meta would integrate its current networks, including Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, into the metaverse, said Brent Mittelstadt, a data ethics research fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute.

“If they keep the same tools that have contributed to the spread of misinformation on their current platforms, it’s hard to say the metaverse is going to help,” said Mittelstadt, who is also a member of the Data Ethics Group at the Alan Turing Institute.

Considering a great deal of the misinformation and hate speech could also arise during private interactions in the metaverse, Rizzoli added, platforms will face the same debates over free speech and censorship when deciding whether to take down harmful content. Do platforms want to have virtual beings approach people and tell them their conversation is not fact-based, or prevent them from having the conversation at all? “This is a debatable issue,” Rizzoli said, “the type of control that you will be subjected to in this new metaverse.”

Defining and determining authenticity in the metaverse could also become more complicated. Tech companies could face tricky questions about the freedom people should enjoy to portray themselves as a member of a different race or gender, said Erick Ramirez, an associate professor at Santa Clara University. Deep fakes—videos or audio that use artificial intelligence to make someone appear to do or say something they didn’t—could evolve to become even more realistic and interactive in a metaverse world.

“There’s more room for deception,” said Ramirez, who recently participated in a roundtable discussion with Clegg about the policy implications of the metaverse. That kind of deceit “takes advantage of a lot of in-built psychology about how we interact with people and how we identify people.”

Virtual Privacy

The metaverse could also compromise user privacy, advocates and researchers said. For instance, people who wear the augmented reality-powered glasses that are currently being developed by Snap Inc. and Meta could end up recording information about other people around them without their knowledge or consent. Users exploring purely virtual worlds could also face digital harassment or stalking from bad actors.

“In the physical world, often you have to do some extra work in order to track somebody, for example, but the online world makes it much easier,” said Neil Chilson, a senior research fellow for technology and innovation at the right-leaning Charles Koch Institute, who also participated in Meta’s roundtable.

Bill Stillwell, Meta product manager for VR privacy and integrity, said in a statement that developers have tools to moderate the experiences they create on Oculus, but the tools can always improve. “We want everyone to feel like they’re in control of their VR experience and to feel safe on our platform.”

Even metaverse supporters such as Chilson and Jarre, the French DJ who will soon hold virtual reality concerts, say regulators around the world will have to draft new rules around privacy, content moderation and other issues to make these digital spaces safe. That might be a tall order for governments that have been struggling for years to pass regulations to govern social media.

“Every technology has a dark side,” said Jarre. “So we need urgently to create regulations.”

Jonathan Victor, a product manager at the open-source developer Protocol Labs, also sees a potential bright side. In his vision of the metaverse, anyone will be able to own a digital 3D version of themselves, exchange cryptocurrency or make a career selling virtual goods they created.

“There’s incredible upside,” Victor said. “The question is, what’s the right way to build it?”