Cuba_Case_Study.pdf

A Beacon of Progress: Cuba's Transition to Sustainable Agriculture

Mattea Kline

3/11/12

Civic Intelligence and Collective Action: Winter Quarter

Introduction:

The transformation of Cuba's food and agricultural system after the collapse of the socialist bloc in 1989, and

the strengthening of the US trade embargo, is a remarkable story in the struggle for food sovereignty that has

been growing throughout the world. Cuba is a nation of unique structure and is rare in the sense that it's people

look upon their government with trust, in the wake of a long history of dependence on powerful nations.

Prior to 1959 and the start of Fidel Castro's reign, Cuba was heavily dependent on the United States for

imports, and before this the island nation was colonized by Spain. From the 1960s to the 1980s Cuba received

heavily subsidized goods from the Soviet Bloc in Europe, such as oil, pesticides, fertilizers and farm equipment

replacements. These inputs made it possible for the nation to develop a high-tech industrial agriculture system.

The Soviet Bloc also purchased sugar from Cuba at subsidized prices allowing Cuba to become a major player in

the world sugar market (Office of Global Analysis, FAS, USDA, 2008).

After the soviet collapse, Cuba fell into an economic crisis and faced a widespread food shortage with

limited resources to recover with. They called it “The Special Period in Time of Peace” which placed the

economy under a wartime austerity program (Funes, García, Bourque, Pérez, and Rosset, 2002). Cuba had to

turn inward for it's survival, not an easy task in a globalizing economy dominated by the US. Cuba, however,

was in a relatively good position to do this, due to the long-held philosophy of social equity and investment in

human resources by the Cuban state. (Funes et al. 2002) To give an example of this preparation, Cuba makes up

2% of the Latin American population, and yet it is the home of 11% of it's scientists (Funes et al. 2002), one can

only imagine that this came about from the Cuban people's access to free, high-quality education and healthcare.

Cuba boasted a 95% literacy rate in 2008, placing it closer in profile to a developed nation than a developing one

(USDA et al, 2008). According to Rosset and Bourque (2002), “...the well-educated and energetic populace put

their dynamism and ingenuity to the task, and the government its commitment to food for all and its support for

domestic science and technology.” (Funes et al, 2002)

I would make the case that this somewhat anomalous transition undertaken by the Cuban people is an

excellent example of civic intelligence working at high efficiency. The nation has not only pioneered alternative

agroecological methods, but it has done so by utilizing every individual willing to get their hands in the dirt.

Cuba has shown that with the proper investment in human capital, and a healthy sense of struggle, an alternative

and sustainable agricultural model can indeed feed a nation. (Funes et al, 2002)

The remainder of this paper will attempt to break down the social process used to transform the Cuban food

system, utilizing the civic intelligence analysis framework of orientation, organization, engagement, intelligence,

products and projects, and resources. My underlying goal is to use this story to demonstrate that with enough

freedom and the right amount of state support, human beings are capable of doing just about anything they

collectively set their minds to, and that the degradation of the environment to accomplish human goals is an

unnecessary evil.

Orientation:

As mentioned in the introduction, Cuba descends from a long history of dependence on powerful countries

such as Spain, the United States, and the former Soviet Union. Prior to the revolution headed by Castro in 1959,

the Cuban landscape hosted a heavy presence of US capital. This agricultural paradigm created a marginalized

peasantry, as the agricultural sector was focused almost exclusively on sugar for export. (Rosset, Machín Sosa,

Roque Jaime, and Ávila Lozano, 2011) Although the government attempted to rectify this marginalization in the

early years after the revolution by initializing widespread agrarian reform, according to Rosset et al (2011) this

process came up against some blockades:

While initial policy was directed at diversifying away from sugar and export dependency, extreme

hostility by the US and the opportunity to join the international socialist division of labor (COMECON)

on favorable terms of trade ended up strengthening the export monocrop emphasis as well as

dependency on imported food, agricultural inputs and implements. (Rosset et al. 2011, 165)

The Agrarian Reform Laws of 1959 and 1963 placed 70% of all farm land in the state's hands, while the rest

was passed to 200,000 peasant families. These families maintained many traditional agroecological practices

passed down through the generations, and went on to form the National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP)

that would go on to work diligently to preserve these old methods (Funes et al. 2002). Integral to the make-up

of this association was the formation of Agricultural Production Cooperatives (CPAs) and Credit and Service

Cooperatives (CCSs).

In the 1970s the Cuban government began recognizing the inefficiency and dependency of the

monocropping system and began investing resources into the study of sustainable agricultural practices. The

Ministry of Agriculture (MINAG), the Ministry of Higher Education (MES), and the Ministry of Education

(MINED) all were adjusted to carry out agroecological research and had integral roles to play in the

development of new practices that built upon the already known traditional methods to envision a system of

self-sufficiency (Funes et al. 2002).

Despite this emphasis on self-sufficiency, in 1989, right before the onslaught of the crisis, Cuba's people

were receiving 57% of their caloric intake and 82% of their pesticides from abroad, while 75% of all export

revenues came from sugarcane, monopolizing 30% of all arable land. While this model might have provided

temporary food security for Cuba, it was foreseeably unsustainable from an ecological standpoint and

dependent solely on positive relations with the Socialist Bloc. (Rosset et al. 2011)

Cuba was about to be shocked out of it's dependence, and it would turn out to be as much of a blessing as it

would be a curse. As we move forward to discuss the organization of the agricultural sector in Cuba, we can see

that the orientation of Cuba is rooted in a long struggle for food sovereignty which has been marked by many

challenges and setbacks along the road. But although Cuba has struggled to define itself as an independent

nation, the common values that run deep throughout its people and state have created a breeding ground for

positive innovation and an autonomous environment for social change.

Organization:

The Cuban agricultural sector has three main components: the state sector, the non-state sector, and the

mixed sector. They all carry out their own roles and interact with each other in different ways. In this section I

will address each in turn.

The State Sector:

Before the Special Period the state sector farms were the largest and most important component of the

nation's agricultural system. In the wake of the Soviet collapse, however, the state farms struggled to produce,

due to a lack of imported agricultural inputs. The state farms were set up for high-tech conventional agriculture,

and were not compatible with the much more low-input technology they were forced to return to during the

crisis (Funes et al. 2002). In a conventional system the tasks of managing a farm are broken up amongst many

workers. This method decreases the knowledge of a particular piece of land that is vital to the ability to gain high

levels of production with low inputs.

In 1993 the Cuban state officially recognized that conventional techniques were not successful within the

new model, and issued a decree that ended the existence of a majority of state farms, reorganizing them into

Basic Units of Cooperative Production (UBPCs). Essentially this fractured the state lands and released it into the

hands of the people, giving it over to them on usufruct terms (free of rent). This action created farmers out of

state workers, enabling greater decision-making autonomy for those who would successfully develop

knowledge and a sense of belonging to the land (Funes et al. 2002). UBPCs are now considered to be part of the

non-state sector. The motivation for breaking up these state farms came from evidence that non-state sector

farms were outstripping state farms in production levels in the years of the Special Period. Private farmers

possessed a more intimate knowledge of their land than did the state workers, and had the ability to make speedy

decisions in order to adapt to the changing economic landscape. Many farmers had preserved traditional

practices that had low input requirements. This was done most notably through the formation of the ANAP

which has worked to preserve traditional practices since 1961 (Rosset et al. 2011).

Remaining lands not given over to UBPCs were formed into New Type State Farms, or GENTS, which were

created to facilitate the process of becoming a full-fledged farmer for former state employees:

The GENTS are completely owned by the state, but worker cooperatives are built upon them, and over

time they take on more financial and management responsibilities. At a minimum, they enter into profitsharing schemes with the underlying state structure. Rather than being state employees, the cooperative

members enter into a contract with the state and the cooperatives profits are shared among the workers

according to their own internal agreements. In the GENTS, both profit and risk are shared between the

state farm and the worker cooperative, but minimum salaries are guaranteed, while ultimate

responsibility for the farm and key management decisions are taken at the state enterprise level. There is

a great deal of flexibility in these experimental arrangements, allowing each division and even particular

enterprises and farms to work out their own arrangements within certain parameters. The final destiny of

a given GENT might be the creation of a UBPC, or it might not. (Funes et al. 2002)

Almost all farms either state or non-state, hold quota requirements with the government, much of which goes

though a food-rationing system which provides a basic subsidized diet, or is used for trade purposes. However,

even with growth in production since the crisis, in 1994, many Cubans were still having difficulty accessing

food. To help remedy this, the state starting allowing the opening of free agricultural markets, where farmers

could sell surplus products at supply and demand prices. This created a strong incentive to bring production

levels even higher, and in 2000 these markets handled 25 to 30% of all produce consumed by Cubans (USDA et

al. 2008)

The state sector is now much smaller and less significant than before these reforms, indicating that the Cuban

people are the innovators and leaders in this agricultural transformation, and that freeing people to find local

solutions is a powerful social mechanism.

The Non-State Sector:

This Campesino or non-state sector consists of CPAs, CCSs, individual farmers (both private and usufruct

tenure) and UBPCs. The two areas of production in this sector are collective, populated by the CPAs and the

UBPCs, and individual, populated by the CCSs and individual family farms. Most individual farmers are

members of CCSs, although some remain completely independent, and most CCS and CPA are members of

ANAP. The UBPCs are organized by the National Farm and Forestry Workers Union (SNTAF) (Rosset et al.

2011). The ANAP has been integral in expanding upon the Campesino-to-Campesino or farmer-to-farmer

training methodolgy which utilizes the knowledge that already exists amongst farmers, bringing it to light for

others to make use of. Below I describe the major production units in Cuban agriculture.

Agricultural Production Cooperatives (CPA): The CPA is the oldest form of collective agriculture in Cuba,

the first formation was in 1977 by farmers volunteering to combine their resources to achieve greater production

levels, increased marketing, and efficiency (Funes et al.2002). Members are compensated according to their

contributions. They make collective decisions in General Assemblies which are insured under the Agricultural

Cooperative Law. They have been leaders in the cooperative agricultural model and have rapidly grown since the

1990s, having attracting many new members from diverse backgrounds who have collectively reshaped the

profile of the peasant farmer.

Basic Units of Agricultural Production (UBPC): As discussed above, UBPCs are former state farms that

have been broken up and given over to the people on permanent usufruct terms. Means of production are sold to

the cooperatives by the state at reduced prices, and is thus private property. The UBPCs continue to sell to the

original distribution chain of the state farm they emerged from, and work under a quota system. Surplus goods

are sold in the free market at supply and demand prices (Funes et al. 2002).

Credit and Service Cooperatives (CCS): At this level of production farmers are in sole, complete, ownership

over their farm and operate it as such. This model simply allows farmers to voluntarily pool resources in order to

receive credit and services from the state. They also might share farming equipment and others resources that

boost production. The CCS, like the CPA is run by General Assembly (Funes et al. 2002).

Individual Farmers: During the fracturing of the state farms in 1993, the state began giving out up to 27

hectares of land in permanent usufruct to families who would cultivate certain crops like coffee, tobacco, and

cocoa. By 1996 their were 43, 015 usufruct farmers. Also given over were small plots in urban environments for

neighborhood gardens, which has been an important aspect of urban dwellers diets, the ANAP works to

incorporate both these types of farmers into their network (Funes et al. 2002).

The Mixed Sector:

The mixed sector consists of joint ventures between the state and foreign companies. This sector is heavily

regulated by the state and only state enterprises can accept foreign capital. Some early crops that received

foreign investment were: citrus, rice, cotton, and tomatoes. (Funes et al.2002) In 2008, an Israeli-Cuban venture

produced more than one-third of all citrus production in Cuba (USDA et al. 2008).

Engagement:

There are multiple ways in which the new agricultural paradigm in Cuba has worked to engage its citizens in

civicly intelligent ways. The state itself has been intelligent in the way that it involves its people and takes cues

from their successes. It has created a participatory process by which the people can be active forces for change in

their country.

Cuba's original agrarian reform laws made the requirement that property rights would not just include the

land itself, but the means to make it productive for themselves and their families, as well as ownership of the

harvest. All legislation after this must be in accordance with it.

The main vehicle for participation in the governmental process for private farmers is the grassroots

organization ANAP, which works to represent the farmer's voice to the government, and represents the majority

of CPA and CCS members. One tool they use to do this is the annual Technical and Financial Plan which they

use to request state assistance. The plan details the real and potential assets, both human and material of every

cooperative member. (Funes et al. 2002)

Another way the people create a voice for themselves is by taking part in the creation of the National

Economic and Social Development Plan, which gives food producers in-depth knowledge of the collective goals

of their region and can thus make decisions based upon a desire to improve the lives of their fellow citizens

(Funes et al. 2002).

One of the most important activities undertaken by ANAP is the furthering of the Campesino-to-Campesino

or farmer-to-farmer teaching and training methodology in the late 1990s. ANAP learned of this methodology

called CAC (Campesino-to-Campesino) from the successful experience of Nicaragua in the mid-1990s. In 1996

ANAP hosted a meeting with CAC delegates from around Latin America, and in 1997 they launched a trial

program (Rosset et al. 2011). Their support for this process has uncovered a goldmine of valuable ecological

knowledge within the Cuban peasantry.

This methodology is based on the idea that rural farmers are more likely to accept new knowledge and new

practices when they are taught by their peers and have concrete evidence that the practice is sound and workable

within their local reality. This grassroots movement's central activity is to coordinate and facilitate the transfer of

agroecological information from those who have successfully innovated a technique, or have remembered a

traditional one, to those who are struggling with a similar problem on their farm. The experienced farmer's land

can thus act as a classroom for those who would benefit from utilizing a given practice. This methodology, one

that has become popular throughout the world, has been especially successful in Cuba because of the friendly

nature of the Cuban state to this type of socially equitable process, and has become an international example for

other nations working to achieve similar goals.

ANAP has been active in reaching out to, and engaging with other nations in agroecological efforts. They are

a member of La Via Campesina (LVC), an international agrarian movement that ANAP has partnered with in

order to research and understand Cuban successes so that they might be shared around the world. This project

was undertaken by members of the International Working Group on Sustainable Peasant Agriculture that LVC

formed for the purpose of such agroecological exchange:

Among other tasks, this Working Group (with a male and female representative from each of the nine

regions in which LVC divides the globe), under the leadership of the National Small Farmers

Association of Cuba (ANAP) and the National Union of Peasant Associations of Mozambique (UNAC),

is charged with strengthening and thickening internal social networks for the exchange of experiences

and support for the agroecology work of member organizations. This includes identifying the most

advanced positive experiences of agroecology, and studying, analyzing and documenting them

(sistematización in Spanish) so that lessons drawn can be shared with organizations in other countries.

(Rosset et al. 2011)

The 2011 study undertaken by Rosset, Machín Sosa, Roque Jaime, and Ávila Lozano was one of the first

tasks that the group was charged with, and was a self-analysis of Cuban progress and the CAC methodology

used to date. As we can see, Cuba has been progressive in engaging it's own people in social development and

agricultural transformation, and has not been shy about sharing their story with those outside the country who

share their passion and drive for change.

Intelligence:

From my perspective, the most important action by the Cuban state in this process, has been recognizing the

voice of the Cuban people. The state has taken important cues from the innovation of private farmers, and has

built upon that innovation, working to support and institutionalize their efforts. This can be seen quite clearly in

the state's response to the spontaneous growth of neighborhood gardens in urban areas. Hugh Warwick wrote in

the “Forum for Applied Research and Public Policy”:

Prior to 1989...urban agriculture was practically unheard of in Havana. Thanks to state provision, there

was adequate food for all and little need to grow any privately. The post-Soviet crisis incited a massive

popular response, initially in the form of gardening in and around the home by Havana's people. This was

soon given a boost by the Cuban Ministry of Agriculture, which created an Urban Agriculture

Department, with the aim of putting all the city's open land into production. By 1998, as a direct result of

this policy, there were over 8,000 officially recognized gardens in Havana, cultivated by 30,000 people

and covering some 30 percent of the available land. And urban agriculture continues to expand, with

many urban areas providing up to 50 percent of their caloric needs. The goal is to grow all of the

horticultural products consumed within the city in urban gardens. (Warwick, 2001)

The urban garden movement in Havana has done much to cultivate community in neighborhoods, increase

self-reliance, and enhance the pride and self-value of its people. It promotes conscious consumerism and social

equity. (Warwick, 2001)

We can see that there is a trend in Cuba of people individually and collectively finding solutions to common

problems. We can also see that there is an equal trend of the state picking up on these innovations and finding a

way to institutionalize them. We saw this at work in the fracturing of the state farms. Smaller farms were

adapting more quickly and had more human resources in their model, and the state responded by adapting their

own practices so that their sector could evolve to be more similar to the non-state model.

Another sign of intelligence, is that Cuban organizers practice regular meta-cognition. This can be seen very

clearly in the Campesino-to-Campesino teaching and training methodology movement, which has built into it

regular debriefing sessions that allow participants to assess progress, successes, and failures so as to modify and

adapt plans for the future. There is a direct feedback loop between the experimentation of farmers on their land,

and the types of agroecological research that is conducted with these farmers in mind. Any practice researched

must be workable within a local reality in Cuba. The methodology itself is also being regularly modified by the

exchange of information between participants (Rosset et al. 2011). This collective process is one that assumes

progress, it cannot become static in nature. The recognition of the evolving, mutable nature of human society is

one of the reasons that Cuba's story is so unique.

Products &Projects:

The authors of Rosset et al (2011) put forth that the concept of agroecology is markedly different from how

most in the North understand organic agriculture. They assert that the conventional understanding of organic

farming simply replaces harmful chemical inputs for less harmful organic-certified ones:

The emphasis is on the adaptation of and application of the principles in accordance with local realities.

For example, in one location soil fertility may be enhanced through worm composting while in another

location it might be through planting green manures; the choice of practices would depend on various

factors including local resources, labor, family conditions, farm size and soil type. This is quite different

from the type of organic farming, common especially in Northern countries, that is based on recipe-like

substitution of toxic inputs with less noxious ones from approved lists, which are also largely purchased

off farm. This kind of input substitution leaves intact dependency on the external input market and the

ecological, social and economic vulnerabilities of moncultures. (Rosset et al. 2011)

Since self-sufficiency is of such vital concern for Cuba considering the United States trade embargo, input

substitution farming would not be a viable model, nor would it provide the numerous benefits that the Cuban

people have reaped from the agroecological model. Some of the practices include: ecological pest management,

inter-cropping, green manures, worm composting, animal traction, and soil management among many others.

(Funes et al. 2002) One of the most prominent outcomes of using highly ecologically integrated methods has

been a high increase in resistance to weather events. During a research visit to Cuba in 2008, the Rosset et al

team observed that 40 days after Hurricane Ike hit, farms that had integrated agroecological practices into their

farms had taken a much less severe hit than industrial farms:

We observed large areas of of industrial monoculture where not five percent of the plants were left

standing. We visited numerous agroecological peasant farms with multi-storied agroforestry farming

systems where Ike had only knocked down the taller 50 percent of the crop plants (tall plantain varieties

and fruit trees), while lower story annual and perennial crops were already noticeably compensating for

those losses with exuberant growth, taking advantage of the added sunlight when upper stories were

tumbled or lost leaves and branches. (Rosset et al.2011)

These observations hold massive implications for the destabilizing nature of industrial moncultures, as well

as the feasibility of alternative methods. If taken seriously, evidence like this can inspire major grassroots strides

to disrupt the prevailing modern agricultural paradigm, as we have seen in the LVC movement. One of the most

important facets of these positive agroecological outcomes is independence from global input markets. In Cuba

the incentive to make these changes came from a lack of access to external inputs due to shaky relations with the

United States.

In 2012, as we see the implosion of the global economy becoming more and more critical, I would predict

that the challenges facing Cuba after the Soviet collapse will become increasingly familiar for the the rest of the

world. This includes highly developed nations such as the US. Cuba has set a standard of sustainable

development that the rest of the world would be wise to emulate (when taking local realities into account). Cuba

has been active in mobilizing this message, hosting a World Forum on Food Sovereignty in Havana in 2001 with

400 delegates from around the world. This forum, convened by the ANAP, brought together people from all

around the world who committed themselves to protecting people's right to feed themselves. The forum also

served to give recognition for Cuba's profound struggle to feed a nation in the shadow of an inhumane blockade

by the United States (Final Declaration of the World Forum on Food Sovereignty, 2001).

Resources:

One of the most intriguing and exciting aspects of Cuba's transformation is the scale of change they

achieved with so few external resources. Through my lens, this is where the power lies. In fact, it could be said

that the extreme actions taken by the United States in limiting Cuba's external resources, although clearly

inhumane, could be viewed much as a cloud with a thick silver lining. It was the necessity of independence

which ultimately drove Cuba to innovate so profoundly and holistically. They were faced with the stark reality

of evolution: adapt or perish. Their success is a beacon for all who believe in and work for social equality and

food sovereignty.

What I take from Cuba's story in considering the resources needed to accomplish these types of goals, is that

social equality and the decision-making autonomy of a nation are both key factors in making this type of

progress. In order to visualize what I mean, imagine for a moment what the Cuban landscape might look like

without the existence of the US trade embargo. In light of the Soviet collapse, Cuba may have been forced to

allow the entrance of large amounts of US capital to make it through the transition, once again marginalizing the

valuable peasantry and pushing agroecological methods deeper into history. We cannot know if this would have

happened, but it seems clear that to a major degree, one of Cuba's most important resources has been a lack of

involvement from the United States.

Conclusion:

To conclude, Cuba has shown that it's people are notably resilient in the face of extremely hostile situations.

I believe that their ability to be so comes from the presence of a strong, yet flexible national identity. The nation

unites at it's heart, not around economic goals or plans, but around a common value system and philosophy that

holds at it's center a deep care for human life. Cuba acts as an example to the world, showing that a welleducated, healthy populace, when shown respect by its state, will help to evolve it's nation and, even, it's

species.

Cuba has shown civic intelligence in such a variety of ways that it has been difficult choosing what to

include here. I have attempted to show what I see as the key ingredients of Cuba's transformation. The most

critical ingredient is that the state and the people share a common goal. Without state support, the

transformation undertaken by Cuba would have been an even steeper, potentially violent climb. Because of

Cuba's struggle, other nations throughout the world who struggle for food sovereignty, now have a wellorganized social process blueprint from which to work.

Of course Cuba's own journey towards self-sufficiency is far from complete, the island nation has simply

jumped several paces ahead of the rest of the world. As the global situation continues to destabilize, I will have

my eyes on Cuba to watch how their story continues to unfold. Several challenges will certainly face them,

especially considering that the US has a growing interest in Cuban markets, and has loosened its embargo

considerably since the beginning of the 21st century. Cuba has been forced to increase its US imports because of

frequent hurricanes hitting the island. (USDA et al. 2008) As we know though, Cuba's agroecological system is

highly adaptable to extreme weather conditions, so it is not even close to being counted out. The Campesino-toCampesino has been strengthening in Cuba, and is being shared around the world thanks to LVC. The food

sovereignty movement won't be ending soon.

References:

Office of Global Analysis, FAS, USDA, March, 2008 “Cuba's Food and Agriculture Situation Report”

Funes, Fernando, García, Luis, Bourque, Martin, Pérez, Nilda, Rosset, Peter, 2002 “Sustainable Agriculture and

Resistance: Transforming Food Production In Cuba” Oakland: Food First Books

Rosset, Peter Micheal, MachÍn Sosa, Braulio, Roque Jaime, Adilén María and Ávila Lozano, Dana Rocío 2011

“The Campesino-to-Campesino agroecology movement of ANAP in Cuba: social process methodology in the

construction of sustainable peasant agriculture and food sovereignty”, Journal of Peasant Studies, 38: 1, 161-191

Warwick, Hugh 2001 “Cuba's Organic Revolution” Forum for Applied Research and Public Policy, Vol. 16

2001 “Final Declaration of the World Forum on Food Sovereignty” Havana, Cuba

2019/01/20

12 The Paradox of Cuban Agriculture

Monthly Review | The Paradox of Cuban Agriculture

The Paradox of Cuban Agriculture

(Jan 01, 2012)

Topics: Ecology

Places: Latin America

Miguel A. Altieri (agroeco3 [at] berkeley.edu) is Profesor of Agroecology at the University of California, Berkeley and President of the Latin American Scientific Society of Agroecology (SOCLA). He is the author of more than 250 journal articles and twelve books. Fernando R. Funes-Monzote (mgahonam [at] enet.cu) is currently a researcher at the Experimental Station Indio Hatuey, University of Matanzas, Cuba. He is one of the founding members of the Cuban Association of Organic Agriculture.

When Cuba faced the shock of lost trade relations with the Soviet Bloc in the early 1990s, food production initially collapsed due to the loss of imported fertilizers, pesticides, tractors, parts, and petroleum. The situation was so bad that Cuba posted the worst growth in per capita food production in all of Latin America and the Caribbean. But the island rapidly re-oriented its agriculture to depend less on imported synthetic chemical inputs, and became a world-class case of ecological agriculture.1 This was such a successful turnaround that Cuba rebounded to show the best food production performance in Latin America and the Caribbean over the following period, a remarkable annual growth rate of 4.2 percent per capita from 1996 through 2005, a period in which the regional average was 0 percent.2

Much of the production rebound was due to the adoption since the early 1990s of a range of agrarian decentralization policies that encouraged forms of production, both individual as well as cooperative—Basic Units of Cooperative Production (UBPC) and Credit and Service Cooperatives (CCS). Moreover, recently the Ministry of Agriculture announced the dismantling of all “inefficient State companies” as well as support for creating 2,600 new small urban and suburban farms, and the distribution of the use rights (in usufruct) to the majority of estimated 3 million hectares of unused State lands. Under these regulations, decisions on resource use and strategies for food production and commercialization will be made at the municipal level, while the central government and state companies will support farmers by distributing necessary inputs and services.3 Through the mid-1990s some 78,000 farms were given in usufruct to individuals and legal entities. More than 100,000 farms have now been distributed, covering more than 1 million hectares in total. These new farmers are associated with the CCS following the campesinoproduction model. The government is busy figuring out how to accelerate the processing of an unprecedented number of land requests.4

The land redistribution program has been supported by solid research- extension systems that have played key roles in the expansion of organic and urban agriculture and the massive artisanal production and deployment of biological inputs for soil and pest management. The opening of local agricultural markets and the existence of strong grassroots organisations supporting farmers—for example, the National Association of Small Scale Farmers (ANAP, Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños), the Cuban Association of Animal Production (ACPA, Asociación Cubana de Producción Animal), and the Cuban Association of Agricultural and Forestry Technicians (ACTAF, Asociación Cubana de Técnicos Agrícolas y Forestales)—also contributed to this achievement.

But perhaps the most important changes that led to the recovery of food sovereignty in Cuba occurred in the peasant sector which in 2006, controlling only 25 percent of the agricultural land, produced over 65 percent of the country’s food.5 Most peasants belong to the ANAP and almost all of them belong to cooperatives. The production of vegetables typically produced by peasants fell drastically between 1988 to 1994, but by 2007 had rebounded to well over 1988 levels (see Table 1). This production increase came despite using 72 percent fewer agricultural chemicals in 2007 than in 1988. Similar patterns can be seen for other peasant crops like beans, roots, and tubers.

Cuba’s achievements in urban agriculture are truly remarkable—there are 383,000 urban farms, covering 50,000 hectares of otherwise unused land and producing more than 1.5 million tons of vegetables with top urban farms reaching a yield of 20 kg/m2 per year of edible plant material using no synthetic chemicals—equivalent to a hundred tons per hectare. Urban farms supply 70 percent or more of all the fresh vegetables consumed in cities such as Havana and Villa Clara.

Table 1. Changes in Crop Production and Agrochemical Use

Crop | Percent production change | Percent change in agrochemical use | |

1988 to 1994 | 1988 to 2007 | 1988 to 2007 | |

General vegetables | -65 | +145 | -72 |

Beans | -77 | +351 | -55 |

Roots and tubers | -42 | +145 | -85 |

Source: Peter Rosset, Braulio Machín-Sosa, Adilén M. Roque-Jaime, and Dana R. Avila-Lozano, “The Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement of ANAP in Cuba,” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (2011): 161-91.

All over the world, and especially in Latin America, the island’s agroecological production levels and the associated research efforts along with innovative farmer organizational schemes have been observed with great interest. No other country in the world has achieved this level of success with a form of agriculture that uses the ecological services of biodiversity and reduces food miles, energy use, and effectively closes local production and consumption cycles. However, some people talk about the “Cuban agriculture paradox”: if agroecological advances in the country are so great, why does Cuba still import substantial amounts of food? If effective biological control methods are widely available and used, why is the government releasing transgenic plants such as Bt crops that produce their own pesticide using genes derived from bacteria?

An article written by Dennis Avery from the Center for Global Food Issues at the Hudson Institute, “Cubans Starve on Diet of Lies,” helped fuel the debate around the paradox. He stated:

The Cubans told the world they had heroically learned to feed themselves without fuel or farm chemicals after their Soviet subsidies collapsed in the early 1990s. They bragged about their “peasant cooperatives,” their biopesticides and organic fertilizers. They heralded their earthworm culture and the predator wasps they unleashed on destructive caterpillars. They boasted about the heroic ox teams they had trained to replace tractors. Organic activists all over the world swooned. Now, a senior Ministry of Agriculture official has admitted in the Cuban press that 84 percent of Cuba’s current food consumption is imported, according to our agricultural attaché in Havana. The organic success was all a lie.6

Avery has used this misinformation to promote a campaign discrediting authors who studied and informed about the heroic achievements of Cuban people in the agricultural field: he has accused these scientists of being communist liars.

The Truth About Food Imports in Cuba

Avery referred to statements of Magalys Calvo, then Vice Minister of the Economy and Planning Ministry, who said in February 2007 that 84 percent of items “in the basic food basket” at that time were imported. However, these percentages represent only the food that is distributed through regulated government channels by means of a ration card. Overall data show that Cuba’s food import dependency has been dropping for decades, despite brief upturns due to natural and human-made disasters. The best time series available on Cuban food import dependency (see Chart 1) shows that it actually declined between 1980 and 1997, aside from a spike in the early 1990s, when trade relations with the former Socialist Bloc collapsed.7

Chart 1. Cuba Food Import Dependency, 1980–1997

Source: José Alvarez, The Issue of Food Security in Cuba, University of Florida Extension Report FE483, downloaded July 20, 2011 from http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FE/FE48300.pdf.

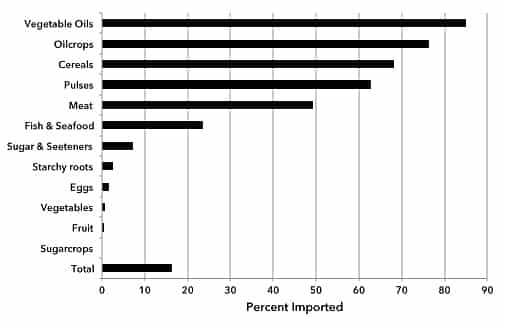

However, Chart 2 indicates a much more nuanced view of Cuba’s agricultural strengths and weaknesses after more than a decade of technological bias toward ecological farming techniques. Great successes have clearly been achieved in root crops (a staple of the Cuban diet), sugar and other sweeteners, vegetables, fruits, eggs, and seafood. Meat is an intermediate case, while large amounts of cooking oil, cereals, and legumes (principally rice and wheat for human consumption, and corn and soybeans for livestock) continue to be imported. The same is true for powdered milk, which does not appear on the graph. Total import dependency, however, is a mere 16 percent—ironically the exact inverse of the 84 percent figure cited by Avery. It is also important to mention that twenty-three other countries in the Latin American-Caribbean region are also net food importers.8

Chart 2. Import Dependence For Selected Foods, 2003

Source: Calculated from FAO Commodity Balances, Cuba, 2003, http://faostat.fao.org.

There is considerable debate concerning current food dependency in Cuba. Dependency rose in the 2000s as imports from the United States grew and hurricanes devastated its agriculture. After being hit by three especially destructive hurricanes in 2008, Cuba satisfied national needs by importing 55 percent of its total food, equivalent to approximately $2.8 billion. However, as the world food price crisis drives prices higher, the government has reemphasized food self-sufficiency. Regardless of whether food has been imported or produced within the country, it is important to recognize that Cuba has been generally able to adequately feed its people. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Cuba’s average daily per capita dietary energy supply in 2007 (the last year available) was over 3,200 kcal, the highest of all Latin American and Caribbean nations.9

Different Models: Agroecology versus Industrial Agriculture

Under this new scenario the importance of contributions of ANAP peasants to reducing food imports should become strategic, but is it? Despite the indisputable advances of sustainable agriculture in Cuba and evidence of the effectiveness of alternatives to the monoculture model, interest persists among some leaders in high external input systems with sophisticated and expensive technological packages. With the pretext of “guaranteeing food security and reducing food imports,” these specific programs pursue “maximization” of crop and livestock production and insist on going back to monoculture methods—and therefore dependent on synthetic chemical inputs, large scale machinery, and irrigation—despite proven energy inefficiency and technological fragility. In fact, many resources are provided by international cooperation (i.e., from Venezuela) dedicated to “protect or boost agricultural areas” where a more intensive agriculture is practiced for crops like potatoes, rice, soybean, and vegetables. These “protected” areas for large-scale, industrial-style agricultural production represent less than 10 percent of the cultivated land. Millions of dollars are invested in pivot irrigation systems, machinery, and other industrial agricultural technologies: a seductive model which increases short-term production but generates high long-term environmental and socioeconomic costs, while replicating a model that failed even before 1990.

Last year it was announced that the pesticide enterprise “Juan Rodríguez Gómez” in the municipality of Artemisa, Havana, will produce some 100,000 liters of the herbicide glyphosate in 2011.10 In early 2011 a Cuban TV News program informed the population about the Cubasoy project. The program, “Bienvenida la Soya,” reported that “it is possible to transform lands that over years were covered by marabú [a thorny invasive leguminous tree] with soybean monoculture in the south of the Ciego de Ávila province.” Supported by Brazilian credits and technology, the project covers more than 15,000 hectares of soybean grown in rotation with maize and aims at reaching 40,500 hectares in 2013, with a total of 544 center pivot irrigation systems installed by 2014. Soybean yields rank between 1.2 tons per hectare (1,100 lbs per acre) under rainfed conditions and up to 1.97 tons per hectare (1,700 lbs per acre) under irrigation. It is not clear if the soybean varieties used are transgenic, but the maize variety is the Cuban transgenic FR-Bt1. Ninety percent of machinery is imported from Brazil—“large tractors, direct seeding machines, and equipment for crop protection”—and considerable infrastructure investments have been made for irrigation, roads, technical support, processing, and transport.

The Debate Over Transgenic Crops

Cuba has invested millions in biotechnological research and development for agriculture through its Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB) and a network of institutions across the country. Cuban biotechnology is free from corporate control and intellectual property-right regimes that exist in other countries. Cuban biotechnologists affirm that their biosafety system sets strict biological and environmental security norms. Given this autonomy and advantages biotechnological innovations could efficiently be applied to solve problems such as viral crop diseases or drought tolerance for which agroecological solutions are not yet available. In 2009 the CIGB planted in Yagüajay, Sancti Spiritus, three hectares of genetically modified corn (transgenic corn FR-Bt1) on an experimental basis. This variety is supposed to suppress populations of the damaging larval stage of the “palomilla del maíz” moth (Spodoptera frugiperda, also known as the fall armyworm). By 2009 a total of 6,000 hectares were planted with the transgenic (also referred to as genetically modified, or GM) variety across several provinces. From an agroecological perspective it is perplexing that the first transgenic variety to be tested in Cuba is Bt corn, given that in the island there are so many biological control alternatives to regulate lepidopteran pests. The diversity of local maize varieties include some that exhibit moderate-to-high levels of pest resistance, offering significant opportunities to increase yields with conventional plant breeding and known agroecological management strategies. Many centers for multiplication of insect parasites and pathogens (CREEs, Centros de Reproducción de Entomófagos y Entomopatógenos) produce Bacillus thuringiensis (a microbial insecticide) and Trichogramma (small wasps), both highly effective against moths such as the palomilla. In addition, mixing corn with other crops such as beans or sweet potatoes in polycultures produces significantly less pest attack than maize grown in monocultures. This also increases the land equivalent ratio (growing more total crops in a given area of land) and protects the soil.

When transgenic Bt maize was planted in 2008 as a test crop, researchers and farmers from the agroecological movement expressed concern. Several people warned that the release of transgenic crops endangered agrobiodiversity and contradicted the government’s own agricultural production plans by diverting the focus from agroecological farming that had been strategically adopted as a policy in Cuba. Others felt that biotechnology was geared towards the interests of the multinational corporations and the market. Taking into account its potential environmental and public health risks, it would be better for Cuba to continue emphasizing agroecological alternatives that have proven to be safe and have allowed the country to produce food under difficult economic and climatic circumstances.

The main demonstrated advantage of GM crops has been to simplify the farming process, allowing farmers to work more land. GM crops that resist herbicides (such as “Roundup Ready” corn and soybeans) and that produce their own insecticide (such as Bt corn) generally do not yield any more than comparable non-GM crops. However, using these GM crops along with higher levels of mechanization (especially larger tractors) have now made it possible for the size of a family corn and soybean farm in the U.S. Midwest to increase from around 240 hectares (600 acres) to around 800 hectares (2,000 acres).

In September 2010 a meeting of experts concerned about transgenic crops was convened with board and staff members from the National Center for Biological Security and the Office for Environmental Regulation and Nuclear Security (Centro Nacional de Seguridad Biológica and the Oficina de Regulación Ambiental y Seguridad Nuclear), institutions entrusted with licensing GM crops. The experts issued a statement calling for a moratorium on GM crops until more information was available and society has a chance to debate the environmental and health effects of the technology. However, until now there has been no response to this request. One positive outcome of the year-long debate on the inconsistency of planting FR-Bt1 transgenic corn in Cuba was the open recognition by the authorities of the potential devastating consequences of GM crops for the small farmer sector. Although it appears that the use of transgenic corn will be limited exclusively to the areas of Cubasoy and other conventional areas under strict supervision, this effort is highly questionable.11

The Paradox’s Outcome—What Does the Future Hold?

The instability in international markets and the increase in food prices in a country somewhat dependent on food imports threatens national sovereignty. This reality has prompted high officials to make declarations emphasizing the need to prioritize food production based on locally available resources.12 It is in fact paradoxical that, to achieve food security in a period of economic growth, most of the resources are dedicated to importing foods or promoting industrial agriculture schemes instead of stimulating local production by peasants. There is a cyclical return to support conventional agriculture by policy makers when the financial situation improves, while sustainable approaches and agroecology, considered as “alternatives,” are only supported under scenarios of economic scarcity. This cyclical mindset strongly undermines the advances achieved with agroecology and organic farming since the economic collapse in 1990.

Cuban agriculture currently experiences two extreme food-production models: an intensive model with high inputs, and another, beginning at the onset of the special period, oriented towards agroecology and based on low inputs. The experience accumulated from agroecological initiatives in thousands of small-and-medium scale farms constitutes a valuable starting point in the definition of national policies to support sustainable agriculture, thus rupturing with a monoculture model prevalent for almost four hundred years. In addition to Cuba being the only country in the world that was able to recover its food production by adopting agroecological approaches under extreme economic difficulties, the island exhibits several characteristics that serve as fundamental pillars to scale up agroecology to unprecedented levels:

Cuba represents 2 percent of the Latin American population but has 11 percent of the scientists in the region. There are about 140,000 high-level professionals and medium-level technicians, dozens of research centres, agrarian universities and their networks, government institutions such as the Ministry of Agriculture, scientific organizations supporting farmers (i.e. ACTAF), and farmers organizations such as ANAP.

Cuba has sufficient land to produce enough food with agroecological methods to satisfy the nutritional needs of its eleven million inhabitants.13 Despite soil erosion, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity during the past fifty years—as well as during the previous four centuries of extractive agriculture—the country’s conditions remain exceptionally favorable for agriculture. Cuba has six million hectares of fairly level land and another million gently sloping hectares that can be used for cropping. More than half of this land remains uncultivated, and the productivity of both land and labor, as well as the efficiency of resource use, in the rest of this farm area are still low. If all the peasant farms (controlling 25 percent of land) and all the UBPC (controlling 42 percent of land) adopted diversified agroecological designs, Cuba would be able to produce enough to feed its population, supply food to the tourist industry, and even export some food to help generate foreign currency. All this production would be supplemented with urban agriculture, which is already reaching significant levels of production.

About one third of all peasant families, some 110,000 families, have joined ANAP within its Farmer to Farmer Agroecological Movement (MACAC, Movimiento Agroecológico Campesino a Campesino). It uses participatory methods based on local peasant needs and allows for the socialization of the rich pool of family and community agricultural knowledge that is linked to their specific historical conditions and identities. By exchanging innovations among themselves, peasants have been able to make dramatic strides in food production relative to the conventional sector, while preserving agrobiodiversity and using much lower amounts of agrochemicals.

Observations of agricultural performance after extreme climatic events in the last two decades have revealed the resiliency of peasant farms to climate disasters. Forty days after Hurricane Ike hit Cuba in 2008, researchers conducted a farm survey in the provinces of Holguin and Las Tunas and found that diversified farms exhibited losses of 50 percent compared to 90 to 100 percent in neighboring farms growing monocultures. Likewise agroecologically managed farms showed a faster productive recovery (80 to 90 percent forty days after the hurricane) than monoculture farms.14 These evaluations emphasize the importance of enhancing plant diversity and complexity in farming systems to reduce vulnerability to extreme climatic events, a strategy entrenched among Cuban peasants.

Most of the production efforts have been oriented towards reaching food sovereignty, defined as the right of everyone to have access to safe, nutritious, and culturally appropriate food in sufficient quantity and quality to sustain a healthy life with full human dignity. However, given the expected increase in the cost of fuel and inputs, the Cuban agroecological strategy also aims at enhancing two other types of sovereignties. Energy sovereignty is the right for all people to have access to sufficient energy within ecological limits from appropriate sustainable sources for a dignified life. Technological sovereignty refers to the capacity to achieve food and energy sovereignty by nurturing the environmental services derived from existing agrobiodiversity and using locally available resources.

Elements of the three sovereignties—food, energy, and technology—can be found in hundreds of small farms, where farmers are producing 70–100 percent of the necessary food for their family consumption while producing surpluses sold to the market, allowing them to obtain income (for example, Finca del Medio, CCS Reinerio Reina in Sancti Spiritus; Plácido farm, CCS José Machado; Cayo Piedra, in Matanzas, belonging to CCS José Martí; and San José farm, CCS Dionisio San Román in Cienfuegos). These levels of productivity are obtained using local technologies such as worm composting and reproduction of beneficial native microorganisms together with diversified production systems such as polycultures, rotations, animal integration into crop farms, and agroforestry. Many farmers are also using integrated food/energy systems and generate their own sources of energy using human and animal labor, biogas, and windmills, in addition to producing biofuel crops such as jatrophaintercropped with cassava.15

Conclusions

A rich knowledge of agroecology science and practice exists in Cuba, the result of accumulated experiences promoted by researchers, professors, technicians, and farmers supported by ACTAF, ACPA, and ANAP. This legacy is based on the experiences within rural communities that contain successful “agroecological lighthouses” from which principles have radiated out to help build the basis of an agricultural strategy that promotes efficiency, diversity, synergy, and resiliency. By capitalizing on the potential of agroecology, Cuba has been able to reach high levels of production using low amounts of energy and external inputs, with returns to investment on research several times higher than those derived from industrial and biotechnological approaches that require major equipment, fuel, and sophisticated laboratories.

The political will expressed in the writings and discourses of high officials about the need to prioritize agricultural self-sufficiency must translate into concrete support for the promotion of productive and energy-efficient initiatives in order to reach the three sovereignties at the local (municipal) level, a fundamental requirement to sustain a planet in crisis.

By creating more opportunities for strategic alliances between ANAP, ACPA, ACTAF, and research centers, many pilot projects could be launched in key municipalities, testing different agroecological technologies that promote the three sovereignties, as adapted to each region’s special environmental and socioeconomic conditions. These initiatives should adopt the farmer-to-farmer methodology that transcends top-down research and extension paradigms, allowing farmers and researchers to learn and innovate collectively. The integration of university professors and students in such experimentation and evaluation processes would enhance scientific knowledge for the conversion to an ecologically based agriculture. It would also help improve agroecological theory, which would in turn benefit the training of future generations of professionals, technicians, and farmers.

The agroecological movement constantly urges those Cuban policy makers with a conventional, Green Revolution, industrial farming mindset to consider the reality of a small island nation facing an embargo and potentially devastating hurricanes. Given these realities, embracing agroecological approaches and methods throughout the country’s agriculture can help Cuba achieve food sovereignty while maintaining its political autonomy.

Notes

- ↩ Peter Rosset and Medea Benjamin, eds., The Greening of the Revolution (Ocean Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1994); Fernando Funes, et. al., eds., Sustainable Agriculture and Resistance (Oakland: Food First Books, 2002); Braulio Machín-Sosa, et. al., Revolución Agroecológica (ANAP: La Habana, 2010).

- ↩ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), The State of Food and Agriculture 2006(Rome: FAO, 2006), http://fao.org.

- ↩ MINAG (Ministerio de la Agricultura), Informe del Ministerio de la Agricultura a la Comisión Agroalimentaria de la Asamblea Nacional, May 14, 2008 (MINAG: Havana, Cuba, 2008).

- ↩ Ana Margarita González, “Tenemos que dar saltos cualitativos,” Interview with Orlando Lugo Fonte, Trabajadores, June 22, 2009, 6.

- ↩ Raisa Pagés, “Necesarios cambios en relaciones con el sector cooperativo-campesino,” Granma, December 18, 2006, 3.

- ↩ Dennis T. Avery, “Cubans Starve on Diet of Lies,” April 2, 2009, http://cgfi.org.

- ↩ Fernando Funes, Miguel A. Altieri, and Peter Rosset, “The Avery Diet: The Hudson’s Institute Misinformation Campaign Against Cuban Agriculture,” May 2009, http://globalalternatives.org.

- ↩ FAO, Ibid.

- ↩ FAOSTAT Food Supply Database, http://faostat.fao.org, accessed July 28, 2011.

- ↩ René Montalván, “Plaguicidas de factura nacional,” El Habanero, November 23, 2010, 4.

- ↩ Fernando Funes-Monzote and Eduardo F. Freyre Roach, eds., Transgénicos ¿Qué se gana? ¿Qué se pierde? Textos para un debate en Cuba (Havana: Publicaciones Acuario, 2009), http://landaction.org.

- ↩ Raúl Castro, “Mientras mayores sean las dificultades, más exigencia, disciplina y unidad se requieren,” Granma, February 25, 2008, 4–6.

- ↩ Fernando Funes-Monzote, Farming Like We’re Here to Stay, PhD dissertation, Wageningen University, Netherlands, 2008.

- ↩ Braulio Machin-Sosa, et. al., Revolución Agroecológica: el Movimiento de Campesino a Campesino de la ANAP en Cuba (ANAP: La Habana, 2010).

- ↩ Fernando Funes-Monzote, et. al., “Evaluación inicial de sistemas integrados para la producción de alimentos y energía en Cuba,” Pastos y Forrajes (forthcoming, 2011).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)