Hakuin Ekaku

Hakuin Ekaku | |

|---|---|

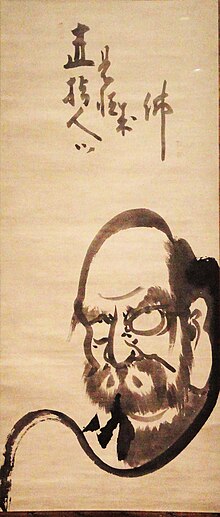

Hakuin Ekaku, self-portrait (1767) | |

| Title | Rōshi |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 1686 |

| Died | c. 1769 |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Rinzai |

| Education | い |

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

Hakuin Ekaku (白隠 慧鶴, January 19, 1686 – January 18, 1769) was one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism. He is regarded as the reviver of the Rinzai school from a moribund period of stagnation, refocusing it on its traditionally rigorous training methods integrating meditation and koan practice.

Biography[edit]

Early years[edit]

Hakuin was born in 1686 in the small village of Hara,[web 1] at the foot of Mount Fuji. His mother was a devout Nichiren Buddhist, and it is likely that her piety was a major influence on his decision to become a Buddhist monk. As a child, Hakuin attended a lecture by a Nichiren monk on the topic of the Eight Hot Hells. This deeply impressed the young Hakuin, and he developed a pressing fear of hell, seeking a way to escape it. He eventually came to the conclusion that it would be necessary to become a monk.

Shōin-ji and Daishō-ji[edit]

At the age of fifteen, he obtained consent from his parents to join the monastic life, and was ordained at the local Zen temple, Shōin-ji. When the head monk at Shōin-ji took ill, Hakuin was sent to a neighboring temple, Daishō-ji, where he served as a novice for three or four years, studying Buddhist texts. While at Daisho-ji, he read the Lotus Sutra, considered by the Nichiren sect to be the king of all Buddhist sutras, and found it disappointing, saying "it consisted of nothing more than simple tales about cause and effect".

Zensō-ji[edit]

At age eighteen, he left Daishō-ji for Zensō-ji, a temple close to Hara.[1] At the age of nineteen, he came across in his studies the story of the Chinese Ch'an master Yantou Quanhuo, who had been brutally murdered by bandits. Hakuin despaired over this story, as it showed that even a great monk could not be saved from a bloody death in this life. How then could he, just a simple monk, hope to be saved from the tortures of hell in the next life? He gave up his goal of becoming an enlightened monk, and not wanting to return home in shame, traveled around studying literature and poetry.[2]

Zuiun-ji[edit]

Travelling with twelve other monks, Hakuin made his way to Zuiun-ji, the residence of Baō Rōjin, a respected scholar but also a tough-minded teacher.[3] While studying with the poet-monk Bao, he had an experience that put him back along the path of monasticism. He saw a number of books piled out in the temple courtyard, books from every school of Buddhism. Struck by the sight of all these volumes of literature, Hakuin prayed to the gods of the Dharma to help him choose a path. He then reached out and took a book; it was a collection of Zen stories from the Ming Dynasty. Inspired by this, he repented and dedicated himself to the practice of Zen.[4]

First awakening[edit]

Eigen-ji[edit]

He again went traveling for two years, settling down at the Eigen-ji temple when he was twenty-three. It was here that Hakuin had his first entrance into enlightenment when he was twenty-four.[5] He locked himself away in a shrine in the temple for seven days, and eventually reached an intense awakening upon hearing the ringing of the temple bell. However, his master refused to acknowledge this enlightenment, and Hakuin left the temple.

Shōju Rōjin[edit]

Hakuin left again, to study for a mere eight months with Shōju Rōjin (Dokyu Etan, 1642–1721).[6] Shoju was an intensely demanding teacher, who hurled insults and blows at Hakuin, in an attempt to free him from his limited understanding and self-centeredness. When asked why he had become a monk, Hakuin said that it was out of terror to fall into hell, to which Shōju replied "You're a self-centered rascal, aren't you!"[7] Shōju assigned him a series of "hard-to-pass" koans. These led to three isolated moments of satori, but it was only eighteen years later that Hakuin really understood what Shōju meant with this.[7]

Hakuin left Shoju after eight months of study,[8] without receiving formal dharma transmission from Shoju Rojin,[9] nor from any other teacher,[web 2] but Hakuin considered himself to be an heir of Shoju Rojin. Today Hakuin is considered to have received dharma transmission from Shoju.[web 3]

Taigi – great doubt[edit]

Hakuin realized that his attainment was incomplete.[10] He was unable to sustain the tranquility of mind of the Zen hall in the midst of daily life.[10] When he was twenty-six he read that "all wise men and eminent priests who lack the Bodhi-mind fall into Hell".[11] This raised a "great doubt" (taigi) in him, since he thought that the formal entrance into monkhood and the daily enactment of rituals was the bodhi-mind.[11] Only with his final awakening, at age 42, did he fully realize what "bodhi-mind" means, namely working for the good of others.[11]

Zen sickness[edit]

Hakuin's early extreme exertions affected his health, and at one point in his young life he fell ill for almost two years, experiencing what would now probably be classified as a nervous breakdown by Western medicine. He called it Zen sickness, and sought the advice of a Taoist cave dwelling hermit named Hakuyu, who prescribed a visualization and breathing practice which eventually relieved his symptoms. From this point on, Hakuin put a great deal of importance on physical strength and health in his Zen practice, and studying Hakuin-style Zen required a great deal of stamina. Hakuin often spoke of strengthening the body by concentrating the spirit, and followed this advice himself. Well into his seventies, he claimed to have more physical strength than he had at age thirty, being able to sit in zazen meditation or chant sutras for an entire day without fatigue. The practices Hakuin learned from Hakuyu are still passed down within the Rinzai school.

Head priest at Shōin-ji[edit]

After another several years of travel, at age 31 Hakuin returned to Shoin-ji, the temple where he had been ordained. He was soon installed as head priest, a capacity in which he would serve for the next half-century. When he was installed as head priest of Shōin-ji in 1718, he had the title of Dai-ichiza, "First Monk":[12]

It was around this time that he adopted the name "Hakuin", which means "concealed in white", referring to the state of being hidden in the clouds and snow of mount Fuji.[13]

Final awakening[edit]

Although Hakuin had several "satori experiences", he did not feel free, and was unable to integrate his realization into his ordinary life.[14] At age 41, he experienced a final and total awakening, while reading the Lotus Sutra, the sutra that he had disregarded as a young student. He realized that the Bodhi-mind means working for the good of every sentient being:[15]

He wrote of this experience, saying "suddenly I penetrated to the perfect, true, ultimate meaning of the Lotus". This event marked a turning point in Hakuin's life. He dedicated the rest of his life to helping others achieve liberation.[14][15]

Practicing the bodhi-mind[edit]

He would spend the next forty years teaching at Shoin-ji, writing, and giving lectures. At first there were only a few monks there, but soon word spread, and Zen students began to come from all over the country to study with Hakuin. Eventually, an entire community of monks had built up in Hara and the surrounding areas, and Hakuin's students numbered in the hundreds. He eventually would certify over eighty disciples as successors.

Is that so?[edit]

A well-known anecdote took place in this period:

Death[edit]

At the age of 83, Hakuin died in Hara, the same village in which he was born and which he had transformed into a center of Zen teaching.

Teachings[edit]

Post-satori practice[edit]

Hakuin saw "deep compassion and commitment to help all sentient beings everywhere"[18] as an indispensable part of the Buddhist path to awakening. Hakuin emphasized the need for "post-satori training",[19][20] purifying the mind of karmic tendencies and

The insight in the need of arousing bodhicitta formed Hakuin's final awakening:

Koan practice[edit]

Hakuin deeply believed that the most effective way for a student to achieve insight was through extensive meditation on a koan. Only with incessant investigation of his koan will a student be able to become one with the koan, and attain enlightenment. The psychological pressure and doubt that comes when one struggles with a koan is meant to create tension that leads to awakening. Hakuin called this the "great doubt", writing, "At the bottom of great doubt lies great awakening. If you doubt fully, you will awaken fully".[21]

Hakuin used a fivefold classification system:[22]

1. Hosshin, dharma-body koans, are used to awaken the first insight into sunyata.[22] They reveal the dharmakaya, or Fundamental.[23] They introduce "the undifferentiated and the unconditional".[24]

2. Kikan, dynamic action koans, help to understand the phenomenal world as seen from the awakened point of view;[25] Where hosshin koans represent tai, substance, kikan koans represent yu, function.[26]

3. Gonsen, explication of word koans, aid to the understanding of the recorded sayings of the old masters.[27] They show how the Fundamental, though not depending on words, is nevertheless expressed in words, without getting stuck to words.[clarification needed][28]

4. Hachi Nanto, eight "difficult to pass" koans.[29] There are various explanations for this category, one being that these koans cut off clinging to the previous attainment. They create another Great Doubt, which shatters the self attained through satori. [30] It is uncertain which are exactly those eight koans.[31] Hori gives various sources, which altogether give ten hachi nanto koans.[32]

5. Goi jujukin koans, the Five Ranks of Tozan and the Ten Grave Precepts.[33][29]

Hakuin's emphasis on koan practice had a strong influence in the Japanese Rinzai-school. In the system developed by his followers, students are assigned koans by their teacher and then meditate on them. Once they have broken through, they must demonstrate their insight in private interview with the teacher. If the teacher feels the student has indeed attained a satisfactory insight into the koan, then another is assigned. Hakuin's main role in the development of this koan system was most likely the selection and creation of koans to be used. In this he didn't limit himself to the classic koan collections inherited from China; he himself originated one of the best-known koans, "You know the sound of two hands clapping; tell me, what is the sound of one hand?". Hakuin preferred this new koan to the most commonly assigned first koan from the Chinese tradition, the Mu koan. He believed his "Sound of One Hand" to be more effective in generating the great doubt, and remarked that "its superiority to the former methods is like the difference between cloud and mud".

Four ways of knowing[edit]

Asanga, one of the main proponents of Yogacara, introduced the idea of four ways of knowing: the perfection of action, observing knowing, universal knowing, and great mirror knowing. He relates these to the Eight Consciousnesses:

- The five senses are connected to the perfection of action,

- Samjna (cognition) is connected to observing knowing,

- Manas (mind) is related to universal knowing,

- Alaya-vijnana is connected to great mirror knowing.[34]

In time, these ways of knowing were also connected to the doctrine of the three bodies of the Buddha (Dharmakāya, Sambhogakāya and Nirmanakaya), together forming the "Yuishiki doctrine".[34]

Hakuin related these four ways of knowing to four gates on the Buddhist path: the Gate of Inspiration, the Gate of Practice, the Gate of Awakening, and the Gate of Nirvana.[35]

- The Gate of Inspiration is initial awakening, kensho, seeing into one's true nature.

- The Gate of Practice is the purification of oneself by continuous practice.

- The Gate of Awakening is the study of the ancient masters and the Buddhist sutras, to deepen the insight into the Buddhist teachings, and acquire the skills needed to help other sentient beings on the Buddhist path to awakening.

- The Gate of Nirvana is the "ultimate liberation", "knowing without any kind of defilement".[35]

Opposition to "Do-nothing Zen"[edit]

One of Hakuin's major concerns was the danger of what he called "Do-nothing Zen" teachers, who upon reaching some small experience of enlightenment devoted the rest of their life to, as he puts it, "passing day after day in a state of seated sleep".[36] Quietist practices seeking simply to empty the mind, or teachers who taught that a tranquil "emptiness" was enlightenment, were Hakuin's constant targets. In this regard he was especially critical of followers of the maverick Zen master Bankei.[37] He stressed a never-ending and severe training to deepen the insight of enlightenment and forge one's ability to manifest it in all activities.[19][20] He urged his students to never be satisfied with shallow attainments, and truly believed that enlightenment was possible for anyone if they exerted themselves and approached their practice with real energy.[20]

Lay teachings[edit]

An extremely well known and popular Zen master during his later life, Hakuin was a firm believer in bringing the wisdom of Zen to all people. Thanks to his upbringing as a commoner and his many travels around the country, he was able to relate to the rural population, and served as a sort of spiritual father to the people in the areas surrounding Shoin-ji. In fact, he turned down offers to serve in the great monasteries in Kyoto, preferring to stay at Shoin-ji. Most of his instruction to the common people focused on living a morally virtuous life. Showing a surprising broad-mindedness, his ethical teachings drew on elements from Confucianism, ancient Japanese traditions, and traditional Buddhist teachings. He also never sought to stop the rural population from observing non-Zen traditions, despite the seeming intolerance for other schools' practices in his writings.

In addition to this, Hakuin was also a popular Zen lecturer, traveling all over the country, often to Kyoto, to teach and speak on Zen. He wrote frequently in the last fifteen years of his life, trying to record his lessons and experiences for posterity. Much of his writing was in the vernacular, and in popular forms of poetry that commoners would read.

Calligraphy[edit]

An important part of Hakuin's practice of Zen was his painting and calligraphy. He seriously took up painting only late in his life, at almost age sixty, but is recognized as one of the greatest Japanese Zen painters. His paintings were meant to capture Zen values, serving as sorts of "visual sermons" that were extremely popular among the laypeople of the time, many of whom were illiterate. Today, paintings of Bodhi Dharma by Hakuin Ekaku are sought after and displayed in a handful of the world's leading museums.

思想

彼は初めて悟りの後の修行(悟後の修行)の重要性を説き、生涯に三六回の悟りを開いたと自称した。その飽くなき求道精神は「大悟十八度、小悟数知らず」という言葉に表象され、現代に伝わっている。また、これまでの語録を再編して公案を洗練させ、体系化した。中でも自ら考案した「隻手音声」と最初の見性体験をした「趙州無字」の問いを、公案の最初の入り口に置き、以後の修行者に必ず参究するようにさせた。

また、菩提心(四弘誓願)の大切さを説いた。菩提心の無き修行者は「魔道に落ちる」と、自身の著作に綴っている。彼は生涯において、この四弘誓願を貫き通し、民衆の教化および弟子を育てた。

禅画と墨蹟

白隠はまた、広く民衆への布教に務め、その過程で禅の教えを表した絵を数多く描いている。その総数は定かではないが、1万点かそれ以上とも言われる[4]。絵の製作年がわかる最も早い作は享保4年(1719年)の「達磨図」(個人蔵)で、縦220cm以上の大作「達磨図」は寛延4年(1751年)の作である(豊橋市正宗寺)。代表作の一つ「大燈国師像」(永青文庫蔵)では、紙面には下書きや描き直しの跡が残り、このような拙によって巧を超えていった技法は、「後の曾我蕭白などに強い感銘を与えた」と想像されている[5]。書家の石川九楊は、白隠の墨蹟について「書法の失調」を捉え、「『書でなくなることによって書である』という逆説によって成り立っている書ならざる書」と評している[6]。白隠の書画の代表的コレクターに、細川護立と山本発次郎がおり、前者のコレクションは永青文庫に収められ、後者は大阪市立近代美術館建設準備室に寄贈されている。

Influence[edit]

Through Hakuin, all contemporary Japanese Rinzai-lineages are part of the Ōtōkan lineage, brought to Japan in 1267 by Nanpo Jomyo, who received dharma transmission in China in 1265.[web 4]

All contemporary Rinzai-lineages stem from Inzan Ien (1751–1814) and Takuju Kosen (1760–1833),[38][39] both students of Gasan Jito (1727–1797). Gasan is considered to be a dharma heir of Hakuin, though "he did not belong to the close circle of disciples and was probably not even one of Hakuin's dharma heirs".[40]

| Linji lineage Linji school | ||||

| Eisai | Linji lineage Linji school | |||

| Myozen | Xutang Zhiyu 虚堂智愚 (Japanese Kido Chigu, 1185–1269) [web 5] [web 6] [web 7] | |||

| Nanpo Shōmyō (南浦紹明?) (1235–1308) | ||||

| Shuho Myocho | ||||

| Kanzan Egen 關山慧玄 (1277–1360) founder of Myōshin-ji |

| |||

| Juō Sōhitsu (1296–1380) | ||||

| Muin Sōin (1326–1410) | ||||

| Tozen Soshin (Sekko Soshin) (1408–1486) | ||||

| Toyo Eicho (1429–1504) | ||||

| Taiga Tankyo (?–1518) | ||||

| Koho Genkun (?–1524) | ||||

| Sensho Zuisho (?–?) | ||||

| Ian Chisatsu (1514–1587) | ||||

| Tozen Soshin (1532–1602) | ||||

| Yozan Keiyō (?–?) | ||||

| Gudō Toshoku (1577–1661) | ||||

| Shidō Bu'nan (1603–1676) | ||||

| Shoju Rojin (Shoju Ronin, Dokyu Etan, 1642–1721) | ||||

| Hakuin (1686–1768) | ||||

| # Gasan Jitō 峨山慈棹 (1727–1797) | ||||

| Inzan Ien 隱山惟琰 (1751–1814) | Takujū Kosen 卓洲胡僊 (1760–1833) | |||

| Inzan lineage | Takujū lineage | |||

| Rinzai school | Rinzai school | |||

Writings[edit]

Hakuin left a voluminous body of works, divided in Dharma Works (14 vols.) and Kanbun Works (4 vols.).[41] The following are the best known and edited in English.

- Orategama (遠羅天釜), The Embossed Tea Kettle, a letter collection. Hakuin, Zenji (1963), The Embossed Tea Kettle. Orate Gama and other works, London: Allen & Unwin

- Yasen kanna (夜船閑話), Idle Talk on a Night Boat, a work on health-improving meditation techniques (qigong).

In modern anthologies[edit]

- Hakuin (2005), The Five Ranks. In: Classics of Buddhism and Zen. The Collected Translations of Thomas Cleary, 3, Boston, MA: Shambhala, pp. 297–305

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Norman Waddell, translator, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 9781570627705

See also[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hakuin Ekaku |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hakuin. |

- Buddhism in Japan

- List of Rinzai Buddhists

- List of Buddhist topics

- Religions of Japan

Notes[edit]

- ^ Takuhatsu (托鉢) is a traditional form of dāna or alms given to Buddhist monks in Japan.[16]

References[edit]

Book references[edit]

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xv.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xvi.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xvii.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xviii–xix.

- ^ Waddell 2010b, p. xvii.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xxi–xxii.

- ^ a b Waddell 2010a, p. xxii.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xxii–xxiii.

- ^ Mohr 2003, p. 311-312.

- ^ a b Waddell 2010a, p. xxv.

- ^ a b c Yoshizawa 2009, p. 44.

- ^ a b Waddell 2010a, p. xxix.

- ^ Stevens 1999, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Waddell 2010b, p. xviii.

- ^ a b Yoshizawa 2009, p. 41.

- ^ A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 9780198605607.

- ^ Reps & Senzaki 2008, p. 22; Kimihiko 1975.

- ^ Low 2006, p. 35.

- ^ a b Waddell 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Hakuin 2010.

- ^ 1939–2013, McEvilley, Thomas (August 1999). Sculpture in the age of doubt. New York. ISBN 9781581150230. OCLC 40980460.

- ^ a b Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 148.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 136.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 136-137.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 148-149.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 137.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 149.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 138.

- ^ a b Hori 2005b, p. 135.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 139.

- ^ Hori 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Hori 2003, p. 23-24.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 151.

- ^ a b Low 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b Low 2006, p. 32-39.

- ^ Hakuin 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Hakuin 2010, p. 125, 126.

- ^ Dumoulin 2005, p. 392.

- ^ Stevens 1999, p. 90.

- ^ Dumoulin 2005, p. 391.

- ^ The Hakuin Study Group has been researching the written works of Hakuin.

Sources[edit]

Published sources[edit]

- Besserman, Perle; Steger, Manfred (2011), Zen Radicals, Rebels, and Reformers, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 9780861716913

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 9780941532907

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Norman Waddell, translator, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 9781570627705

- Hakuin; Waddell, Norman (2010b), The Essential teachings of Zen Master Hakuin, Shambhala Classics

- Hori, Victor Sogen (2005b), The Steps of Koan Practice. In: John Daido Loori,Thomas Yuho Kirchner (eds), Sitting With Koans: Essential Writings on Zen Koan Introspection, Wisdom Publications

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, boston & london: Shambhala

- Mohr, Michel. "Emerging from Non-duality: Kōan Practice in the Rinzai Tradition since Hakuin." In The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, edited by S. Heine and D. S. Wright. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Mohr, Michel (2003), Hakuin. In: Buddhist Spirituality. Later China, Korea, Japan and the Modern World; edited by Takeuchi Yoshinori, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Trevor Leggett, The Tiger's Cave, ISBN 0-8048-2021-X, contains the story of Hakuin's illness.

- Stevens, John (1999), Zen Masters. A Maverick, a Master of Masters, and a Wandering Poet. Ikkyu, Hakuin, Ryokan, Kodansha International

- Waddell, Norman, trans. "Hakuin's Yasenkanna." In The Eastern Buddhist (New Series) 34 (1):79–119, 2002.

- Waddell, Norman (2010a), Foreword to "Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin", Shambhala Publications

- Waddell, Norman (2010b), Translator's Introduction to "The Essential teachings of Zen Master Hakuin", Shambhala Classics

- Yampolsky, Philip B. The Zen Master Hakuin: Selected Writings. Edited by W. T. de Bary. Vol. LXXXVI, Translations from the Oriental Classics, Records or Civilization: Sources and Studies. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971, ISBN 0-231-03463-6

- Yampolsky, Philip. "Hakuin Ekaku." The Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Mircea Eliade. Vol. 6. New York: MacMillan, 1987.

- Reps, Paul; Senzaki, Nyogen (2008), Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings, ISBN 978-0-8048-3186-4

- Yoshizawa, Katsuhiro (1 May 2009), The Religious Art of Zen Master Hakuin, Catapult, ISBN 978-1-58243-986-0

- Kimihiko, Naoki (1975), Hakuin zenji : KenkoÌ"hoÌ" to itsuwa (Japanese), Nippon Kyobunsha co.,ltd., ISBN 978-4531060566

Web-sources[edit]

- ^ Shoinji Temple

- ^ James Ford (2009), Teaching Credentials in Zen

- ^ Zen Buddhism: from perspective of Japanese Soto & Rinzai Zen Schools Archived 2012-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rinzai-Obaku Zen – What is Zen? – History

- ^ Korinji – Lineage

- ^ Origins of the Ōtōkan Rinzai Lineage in Japan

- ^ Rinzai (Lin-chi) Lineage of Joshu Sasaki Roshi

Further reading[edit]

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Norman Waddell, translator, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 9781570627705

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, boston & london: Shambhala

- Yoshizawa, Katsuhiro (2010), The Religious Art of Zen Master Hakuin, Counterpoint Press

- Spence, Alan (2014), Night Boat: A Zen Novel, Canongate UK, ISBN 978-0857868541