Boston martyrs

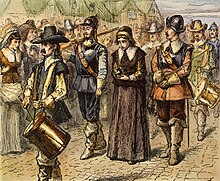

The Boston martyrs is the name given in Quaker tradition[1] to the three English members of the Society of Friends, Marmaduke Stephenson, William Robinson and Mary Dyer, and to the Barbadian Friend William Leddra, who were condemned to death and executed by public hanging for their religious beliefs under the legislature of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1659, 1660 and 1661. Several other Friends lay under sentence of death at Boston in the same period, but had their punishments commuted to that of being whipped out of the colony from town to town.

"The hanging of Mary Dyer on the Boston gallows in 1660 marked the beginning of the end of the Puritan theocracy and New England independence from English rule. In 1661 King Charles II explicitly forbade Massachusetts from executing anyone for professing Quakerism. In 1684 England revoked the Massachusetts charter, sent over a royal governor to enforce English laws in 1686, and in 1689 passed a broad Toleration act."[2][3]

Boston origins[edit]

The settlement of Boston was founded by Puritan chartered colonists of the Massachusetts Bay Colony under John Winthrop, and acquired the name of Boston soon after the arrival of the Winthrop Fleet in 1630. It was named after Boston, Lincolnshire, in England. During the 1640s, as the English Civil War reached its climax, the founder of English Quakerism, George Fox (1624–1691), discovered his religious vocation. Under the Puritan English Commonwealth led by Oliver Cromwell, Quakers in England were persecuted, and during the 1650s various groups of Quakers left England as 'Publishers of Truth'.[citation needed]

Mary Dyer's early work[edit]

Mary Dyer was an English Puritan living in Boston, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1637 she supported Anne Hutchinson, who believed that God 'spoke directly to individuals' and not only through the clergy. They began organizing Bible study groups in violation of Massachusetts Colony laws, and for this 'Antinomian heresy' Mary Dyer, her husband William Dyer, Anne Hutchinson, and others were banished from the colony in January 1637/8. They relocated at Portsmouth in the Rhode Island colony, joined by the religious group they had founded.

Voyages of the Speedwell (1656) and the Woodhouse (1657)[edit]

Leaving England on 30 May, the Speedwell under captain Robert Locke arrived at Boston on 27 July 1656, having on board eight Quakers including Christopher Holder, John Copeland and William Brend.[4][5] As required by Boston law, the authorities were notified of their arrival, and all eight were immediately brought before the court. They were imprisoned on orders of Governor John Endecott, under a sentence of banishment. Shortly after this, Mary Dyer and Anne Burden arrived in Boston from Rhode Island and also were imprisoned. Eleven weeks later, Holder, Copeland and the six other Quakers from the Speedwell were deported to England; however, they immediately took steps to return.[6]

In July 1657 an additional party of Quakers for Massachusetts (including six of those from the Speedwell), set out on the Woodhouse, undertaken by her owner Robert Fowler of Bridlington Quay, Yorkshire, England. The Woodhouse made land at Long Island. Five were set ashore at the Dutch plantation of New Amsterdam (New York): Robert Hodgson, Richard Doudney, Sarah Gibbons, Mary Weatherhead, and Dorothy Waugh.[7]

Confrontations with Governor Endecott[edit]

Mary Dyer, who had returned to England with Roger Williams and John Clarke in 1652, heard the ministry of George Fox and became a Friend. She and her husband returned to Rhode Island in 1657. In time, Holder and Copeland returned to Massachusetts and met with other Friends in Sandwich and other towns. However, they were arrested at Salem by Endecott's order and were imprisoned for several months. They were released, but in April 1658 were rearrested at Sandwich and whipped. In June they went to Boston and were again arrested, and Copeland's right ear was cut off as a judicial penalty. Katherine Scott, Anne Hutchinson's sister, spoke up for them and was imprisoned and whipped.[8]

Boston law against Quakers[edit]

At the end of 1658, the Massachusetts legislature, by a bare majority, enacted a law that every member of the sect of Quakers who was not an inhabitant of the colony but was found within its jurisdiction should be apprehended without warrant by any constable and imprisoned, and on conviction as a Quaker, should be banished upon pain of death, and that every inhabitant of the colony convicted of being a Quaker should be imprisoned for a month, and if obstinate in opinion should be banished on pain of death. Some Friends were arrested and expelled under this law.[9] At that time various punishments of Friends were vigorously and cruelly acted upon, as a letter of James Cudworth written from Scituate in 1658 reveals.[10]

Stephenson and Robinson[edit]

Marmaduke Stephenson had been a ploughman in Yorkshire in England in 1655, when (as he wrote), "as I walked after the plough, I was filled with the love and presence of the living God, which did ravish my heart". Leaving his family to the Lord's care, he followed the divine prompting to Barbados in June 1658, and after some time there he heard of the new Massachusetts law and passed over to Rhode Island. There he met William Robinson (a merchant of London), another Friend from the company of the Woodhouse, and in June 1659 with two others they went into the Massachusetts colony to protest at their laws. Mary Dyer went for the same purpose. The three were arrested and banished, but Robinson and Stephenson returned and were again imprisoned.[11] During their imprisonment and trial, the ministers Zechariah Symmes and John Norton were instructed to attend them "with religious conversation fitted for their condition".[12] Mary Dyer went back to protest at their treatment, and was also imprisoned. In October 1659, Endecott, according to the instruction of the law previously passed, pronounced sentence of death upon the three.

Executions at Boston Neck[edit]

The execution day was Thursday 27 October (the usual weekly meeting day for the Church in Boston) 1659, and the gallows stood on Boston Neck, the narrow isthmus of land that connected Boston to the mainland.[13] They spoke as they were led there, but their words were drowned out by the sound of drums. After they had taken leave of one another, William Robinson ascended the ladder. He told the people it was their day of visitation, and desired them to mind the light within them, the light of Christ, his testimony for which he was going to seal with his blood. At this the Puritan minister (John Wilson) shouted, "Hold thy tongue, thou art going to die with a lie in thy mouth." The rope was adjusted, and as the executioner turned the condemned man off, he said with his dying breath, "I suffer for Christ, in whom I live and for whom I die." Marmaduke Stephenson next climbed the ladder and said, "Be it known unto all this day that we suffer not as evil-doers, but for conscience sake." As the ladder was pushed away, he said, "This day shall we be at rest with the Lord."[14]

In memory of this, October 27 is now International Religious Freedom Day to recognize the importance of Freedom of religion.[15]

Mary Dyer's and William Leddra's executions[edit]

Mary Dyer also stepped up the ladder, her face was covered and the halter put round her neck, when the cry was raised, "Stop! for she is reprieved." She was again banished, but returned in May 1660. Since her reprieve, others, both colonists and visiting Friends, had brought themselves within the capital penalty, but the authorities had not ventured to enforce it. After ten days Endecott, at the bidding of the courts, sent for her, and asked her if she were the same Mary Dyer who had been there before. On her avowing this, the death sentence was passed and executed.[16] Another Friend, William Leddra of Barbados, was hanged on 14 March 1661.[17][18]

The King's Missive, and Wenlock Christison's words[edit]

Others lay in prison awaiting sentence but were set at liberty, and a new law was passed substituting whipping out of the colony from town to town. Shortly after, the 'King's Missive' reached Boston and showed the royal disapproval of the policy of persecution.[19] When the last Friend to be condemned to death (Wenlock Christison, afterwards released) had received his sentence, he had said:

References[edit]

- ^ The term martyr is problematic in Quakerism, which does not thereby uphold any theological distinction of sanctity, but records the sufferings, witness and constancy of Friends who were persecuted for the sake of the Spirit.

- ^ Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: a comprehensive encyclopedia

- ^ Johan Winsser Mary Dyer: Quaker Martyr and Enigma

- ^ Charles Frederick Holder, LL.D, The Holders of Holderness. A History and Genealogy of the Holder Family with especial reference to Christopher Holder (Author, California (1902)), pp. 22-26 (Internet Archive). The text includes a full transcript of the original 1656 shipping list in the Massachusetts Colonial Records: the eight were Christopher Holder (25), William Brend (40), John Copeland (28), Thomas Thurston (34), Mary Prince (21), Sarah Gibbons (21), Mary Weatherhead (26), Dorothy Waugh (20).

- ^ The Speedwell carried the same name as the ship which set out for the Americas with the Mayflower in 1620 but was forced to return to Plymouth having transferred her party of Pilgrims to the Mayflower.

- ^ James Bowden, History of the Society of Friends in America (Charles Gilpin, London 1850), Vol. I, pp. 42-51.

- ^ 'A true relation of the voyage undertaken by me, Robert Fowler (etc)' in James Bowden, History of the Society of Friends in America (Charles Gilpin, London 1850), Vol. I, pp. 63-67. Read here.

- ^ See J. Besse, A Collection of the Sufferings of the People called Quakers (Luke Hinde, London 1753), Vol. 2, Chapter 5 at pp. 177 ff. Read here

- ^ Christian Life, Faith and Thought in the Society of Friends. Book of Discipline Part 1 (Friends Book Centre, London 1921), p. 31.

- ^ 'James Cudworth's Letter, written in the tenth month, 1658', in Appendix to Richard P. Hallowell, The Quaker Invasion of Massachusetts (Houghton, Mifflin & Co, Boston/Riverside Press, Cambridge 1883), pp. 162-72. Read here

- ^ Trial and Testament of Marmaduke Stephenson, in J. Besse, A Collection of the Sufferings of the People called Quakers, from 1650 to 1689 (Luke Hinde, London 1753), Vol. 2, pp. 198-202. Read here.

- ^ J.B. Felt, The Ecclesiastical History of New England, 2 vols., (Congregational Library Association, Boston 1862), II, p. 212 (Hathi Trust).

- ^ Canavan, Michael J. (1911). "Where Were the Quakers Hanged?". Proceedings of the Bostonian Society: 37–49 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ J. Besse, A Collection of the Sufferings of the People called Quakers, 1753, Vol. 2, pp. 203-05.

- ^ Margery Post Abbott (2011). Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers). Scarecrow Press. pp. 102. ISBN 978-0-8108-7088-8.

- ^ Rogers, Horatio, 2009. Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston pp.1-2. BiblioBazaar, LLC

- ^ ODNB article by John C. Shields, ‘Leddra, William (d. 1661)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, May 2007 [1], accessed 16 August 2009]

- ^ G. Bishop, New England Judged, Part 1 (London 1661). Reprint of the 1703 edition, pp.189-218.

- ^ Text: New-England Judged, pp. 214-15. See also John Greenleaf Whittier, The King's Missive, and other poems (Houghton, Mifflin & Co., Boston 1881), 'The King's Missive. 1661' at pp. 9-17. Read here.

- ^ Christian Life, Faith and Thought (1921), pp. 31-32.

Further reading[edit]

- Christian Life, Faith and Thought in the Society of Friends of Great Britain. Book of Discipline Part 1 (Friends Book Centre, London 1921), 28-34.

- Joseph Besse, A Collection of the Sufferings of the People called Quakers, from 1650 to 1689 (Luke Hinde, London 1753), Volume 2, Chapter 5.

- George Bishop, New England Judged, Not by Man's, but by the Spirit of the Lord: And The Summe sealed up of New-England's Persecutions (Robert Wilson, 1661). An Appendix to the Book, Entituled, New-England Judged, The Second Part. (London, 1667). Reprint of the abbreviated 1703 edition, (T. Sowle, London 1703), (Hathi Trust).

- Winsser, Johan (2017). Mary and William Dyer: Quaker Light and Puritan Ambition in Early New England. North Charleston, South Carolina: CreateSpace (Amazon). ISBN 1539351947.