Walter Wink and Greg Boyd on the Problem of Evil

MARCH 22, 2011 BY ROGER E. OLSON

28 COMMENTS

I admit that I’m very late coming to read Walter Wink (professor emeritus of Auburn Theological Seminary, New York City). People have recommended his books to me for years and I’ve managed to avoid reading even one of them! From what I knew about his central thesis it seemed to me very similar to the thesis of Walter Rauschenbusch in A Theology for the Social Gospel–that there is a “kingdom of evil” that causes much, if not all, of the evil in the social world. Also, his books seemed exceptionally long! So I read reviews and articles and thought I got the point that way.

Recently I’ve been re-reading my former colleague and friend Greg Boyd’s book Satan and the Problem of Evil. (It’s also a very big book! Why can’t people keep their books briefer? 🙂 I was privileged to work alongside Greg for several years and I remember our many talks about the subjects he deals with in that book. (In fact, I take some credit for helping launch Greg’s career as a theologian; it was I who choose his application out of a stack of applications for an open position in theology and insisted that we interview him. I remember how he absolutely hit the ball out of the ballpark in his interviews. Needless to say, he was hired and became one of the college’s most popular teachers and an influential evangelical scholar.)

During some recent travels I happened to see one of Wink’s smaller books–The Powers that Be (Doubleday, 1999)–at a used bookstore. I bought it and read it with real benefit. It is a sort of summary of Wink’s “Powers” trilogy. I see amazing parallels between Boyd’s arguments about evil and Winks’. There are also very significant differences. And I find myself somewhat caught between them with regard to those differences.

The central point of agreement and disagreement has to do with the “powers and principalities” against which Paul says we wrestle (as opposed to “flesh and blood”) in Ephesians 6:12. Who are the “rulers of the darkness of this world” against which we should fight? In other words, both books–Satan and the Problem of Evil and The Powers that Be (and Wink’s earlier Powers trilogy)–are about spiritual warfare.

In contrast to many Christian thinkers past and present Greg believes the Bible commands us to fight against real demons that create havoc and calamity in the world. This is, he says, the clear biblical worldview–a “spiritual warfare worldview.” He attributes much horror in the world–from child abuse to genocide–to the influence of these demonic beings and their captain Satan. Of course, he doesn’t say with Flip Wilson “the devil made me do it” when talking about human responsibility for sin and evil. As an Arminian, Greg believes sin and evil are our doing, but our doing them is instigated and empowered by Satan and his minions. Greg takes this into the social realm and argues that the powers and principalities are behind social oppression and exploitation.

One reason I always had some problems with Greg’s view is my own experiences. I grew up Pentecostal and many of my relatives and acquaintances seemed to see “demons on doorknobs.” Then, my first full time teaching position was at a charismatic university where, in chapel, I heard too much talk about Satan. The founder and his son talked to the devil more than to God! (E.g., “Satan, get your hands off God’s people,” etc.) Once, while I was teaching there, the founder decided to try to exorcise a demon from a student and humiliated her horribly. During a chapel service he asked students (and others) who felt oppressed to stand. He singled out a young female student and, from the pulpit, tried to tell her he “discerned” she was demon possessed. Of course, she denied it and back and forth it went. He wouldn’t give up. I felt so sorry for her. One time the founder preached in chapel–just days after his newborn grandson died in the hospital. He declared that he felt Satan come into the room where the child lay in its crib and take it away. His point? That if the hospital he (the founder) was building were finished (and he needed millions to finish it!) his grandson would have been born there and not subject to Satan’s wiles.

I came away from those experiences very eager to avoid any more talk of a real, live, active devil or demons (while holding onto belief in the supernatural world). Oddly, however, I noticed that the more mainstream evangelicals I associated with after that talked a lot about demons being real and active “on the mission field.” But they tended to shy away from any talk of Satan or demons here in the good old U.S.A. Something seemed wrong with that. And yet I didn’t really want to go down that road either (because of my bad experiences).

Then I met and got to know Greg–a man with a stellar education in philosophy and theology and with a brilliant mind–who knows a lot about the power of demons. During his ministry he has had many “power encounters” with them and exorcised more than a few from people who sought his help. His stories about all that fit perfectly what I read in the New Testament. But, of course, the academic world absolutely shuns such talk. Except as it is packaged by Walter Wink!

Wink also believes in a demonic realm that is real and active in the world–but from a different perspective than Greg’s. Wink, a mainstream (if that’s a meaningful concept in our postmodern world!) Protestant with a decidedly liberal bent theologically, recovered a sense of the demonic from within that theological perspective. Like Greg, Wink believes demons are real and not just “the evil that we do.” They are not just personification of human evil deeds. There are, Wink argues, very real and powerful demonic forces in the world that influence it towards evil.

The difference is that while Greg believes these powers and principalities are personal beings, Wink believes they are social realities–systems that oppress and exploit people. They are “violence-prone systems of power and domination.” Unlike other liberal Protestants who talk about “the demonic” such as Tillich, however, Wink believes these systems are not just negative forces built into the universe by non-being. He invests them with almost personal reality while stopping short of viewing them as personal entities such as the Bible depicts and Greg Boyd believes in.

Both Wink and Greg criticize the “myth of redemptive violence” that is actively promoted by these powers and principalities. Christians are to wage spiritual warfare against them and against their influence. But for Greg, spiritual warfare includes power encounters and intercessory prayer and even exorcism. For Wink, spiritual warfare is social action that unmasks the powers and exposes them for what they are–destructive to human and non-human life. For Wink, liberation movements in Latin America, for example, are engaged in spiritual warfare (insofar as they are fighting against systems that dominate and exploit people).

What’s odd is that for Wink these powers are NOT merely the products of human decisions and actions. They have a different kind of ontological reality not reducible to humanity and its thoughts and deeds. They are malevalent systems with semi-autonomous reality although they do not fly around in the air and get into people. At least in The Powers that Be Wink leaves their origin and exact nature unexplained and perhaps inexplicable. The main point, however, is that they can be defeated. For some reason, God, Wink says, does not defeat them by himself. He allows them to carry on their anarchic work in the world and expects us to fight against them in the power of his might.

What I find very interesting are the parallels between Greg’s worldview and Wink’s. The main difference, it appears, lies in their different views of what these powers and principalities are. Greg clearly sees them, as he believes the New Testament implies, as fallen angelic beings. Wink sees them as having ontological being and power beyond nature but not supernatural in the sense of invisible entities with human-like personal qualities.

As I finished reading The Powers that Be I had the distinct impression that bringing these two theologians together in the same room to talk about their similarities and differences would be an amazing experience. I’m sure that Greg would push Wink on the exact nature of the powers. Wink seems to leave them in a kind of ontological grey area–neither personal nor impersonal. Clearly he is uncomfortable with personalizing them in the way Greg does. He calls that “over belief.” But he calls his fellow liberals’ views of the spiritual world “under belief.” He leaves unclear exactly where he stands with regard to the powers’ origins and ontological status. I fully undestand that because of my bad experiences with people who invest too much human-like personal reality in demons. However, I’m uncomfortable with leaving the principalities and powers in this kind of unstable middle area–between naturalism and supernaturalism. Wink SEEMS to want to believe in them as Greg does, but he is clearly held back by a modern worldview based on naturalism–which he criticizes!

What I think both Greg and Wink have right is the powerful influences of suprahuman powers and principalities in the world that are NOT merely instruments of God or creations of our own evil decisions and actions. I personally cannot bring myself to regard the genocidal horrors of the 20th century as merely the results of misguided human decisions and actions. Something demonic that the New Testament calls “the rulers of the darkness” must have been at work for Hitler and others like him to accomplish what they did. And Christians ought to be involved in some kind of spiritual warfare beyond praying “if it be thy will” (when interceding on behalf of suffering people). Both Greg and Wink remind us, in somewhat different ways, that evil cannot be reduced to human decisions and actions and that our struggle against evil must include some kind of power encounters–whether with personal demons or suprapersonal systems.

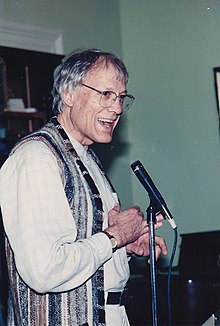

Walter WinkCredit...Fellowship of Reconciliation/forusa.org

Walter WinkCredit...Fellowship of Reconciliation/forusa.org