Jakob Böhme

Jakob Böhme | |

|---|---|

Jakob Böhme (anonymous portrait) | |

| Born | 24 April 1575 Alt Seidenberg (now Stary Zawidów, Poland) near Görlitz, Upper Lusatia, Lands of the Bohemian Crown, Holy Roman Empire (now split between Görlitz, Germany and Zgorzelec, Poland) |

| Died | 17 November 1624 Görlitz, Upper Lusatia, Lands of the Bohemian Crown, Holy Roman Empire (now split between Görlitz, Germany and Zgorzelec, Poland) |

| Other names | Jacob Boehme, Jacob Behmen (English spellings) |

| Era | Early modern philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Christian mysticism |

Notable ideas | Boehmian theosophy The mystical being of the deity as the Ungrund ("unground", the ground without a ground)[1] |

show Influences | |

show Influenced | |

Part of a series onHermeticism Mythology MythologyHermes Trismegistus Hermetic arts Astrology Alchemy MagicHermetic writings Liber Hermetis (astrological) Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus Corpus Hermeticum Asclepius Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth Korē kosmou Cyranides The Book of the Secrets of the Stars The Secret of Creation Emerald Tablet Kitāb al-Isṭamākhīs Liber Hermetis de alchemiaRelated historical figures (ancient and medieval) Zosimos of Panopolis Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (may be legendary) Abū Maʿshar Ibn Umayl Maslama al-Qurṭubī Aḥmad al-BūnīRelated historical figures (early modern) Marsilio Ficino Lodovico Lazzarelli Giovanni da Correggio Pico della Mirandola Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa Paracelsus John Dee Giordano Bruno Jakob Böhme Robert Fludd Christian Rosenkreuz (legendary, see Rosicrucianism)Modern offshoots As above, so below Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn Kybalion |

Jakob Böhme (/ˈbeɪmə, ˈboʊ-/;[2] German: [ˈbøːmə]; 24 April 1575 – 17 November 1624) was a German philosopher, Christian mystic, and Lutheran Protestant theologian. He was considered an original thinker by many of his contemporaries[3] within the Lutheran tradition, and his first book, commonly known as Aurora, caused a great scandal. In contemporary English, his name may be spelled Jacob Boehme; in seventeenth-century England it was also spelled Behmen, approximating the contemporary English pronunciation of the German Böhme.

Böhme had a profound influence on later philosophical movements such as German idealism and German Romanticism.[4] Hegel described Böhme as "the first German philosopher".

Biography[edit source]

Böhme was born on 24 April 1575[5][6] at Alt Seidenberg (now Stary Zawidów, Poland), a village near Görlitz in Upper Lusatia, a territory of the Kingdom of Bohemia. His father, George Wissen, was Lutheran, reasonably wealthy, but a peasant nonetheless. Böhme was the fourth of five children. Böhme's first job was that of a herd boy. He was, however, deemed to be not strong enough for husbandry. When he was 14 years old, he was sent to Seidenberg, as an apprentice to become a shoemaker.[7] His apprenticeship for shoemaking was hard; he lived with a family who were not Christians, which exposed him to the controversies of the time. He regularly prayed and read the Bible as well as works by visionaries such as Paracelsus, Weigel and Schwenckfeld, although he received no formal education.[8] After three years as an apprentice, Böhme left to travel. Although it is unknown just how far he went, he at least made it to Görlitz.[7] In 1592 Böhme returned from his journeyman years. By 1599, Böhme was master of his craft with his own premises in Görlitz. That same year he married Katharina, daughter of Hans Kuntzschmann, a butcher in Görlitz, and together he and Katharina had four sons and two daughters.[8][9]

Böhme's mentor was Abraham Behem who corresponded with Valentin Weigel. Böhme joined the "Conventicle of God's Real Servants" - a parochial study group organized by Martin Möller. Böhme had a number of mystical experiences throughout his youth, culminating in a vision in 1600 as one day he focused his attention onto the exquisite beauty of a beam of sunlight reflected in a pewter dish. He believed this vision revealed to him the spiritual structure of the world, as well as the relationship between God and man, and good and evil. At the time he chose not to speak of this experience openly, preferring instead to continue his work and raise a family.[citation needed]

In 1610 Böhme experienced another inner vision in which he further understood the unity of the cosmos and that he had received a special vocation from God.[citation needed]

The shop in Görlitz, which was sold in 1613, had allowed Böhme to buy a house in 1610 and to finish paying for it in 1618. Having given up shoemaking in 1613, Böhme sold woollen gloves for a while, which caused him to regularly visit Prague to sell his wares.[7]

Aurora and writings[edit source]

| There are as many blasphemies in this shoemaker's book as there are lines; it smells of shoemaker's pitch and filthy blacking. May this insufferable stench be far from us. The Arian poison was not so deadly as this shoemaker's poison. |

| — Gregorius Richter following the publication of Aurora.[10] |

Twelve years after the vision in 1600, Böhme began to write his first book, Die Morgenroete im Aufgang (The rising of Dawn). The book was given the name Aurora by a friend; however, Böhme originally wrote the book for himself and it was never completed.[11] A manuscript copy of the unfinished work was lent to Karl von Ender, a nobleman, who had copies made and began to circulate them. A copy fell into the hands of Gregorius Richter, the chief pastor of Görlitz, who considered it heretical and threatened Böhme with exile if he continued working on it. As a result, Böhme did not write anything for several years; however, at the insistence of friends who had read Aurora, he started writing again in 1618. In 1619 Böhme wrote "De Tribus Principiis" or "On the Three Principles of Divine Being". It took him two years to finish his second book, which was followed by many other treatises, all of which were copied by hand and circulated only among friends.[12] In 1620 Böhme wrote "The Threefold Life of Man", "Forty Questions on the Soul", "The Incarnation of Jesus Christ", "The Six Theosophical Points", "The Six Mystical Points". In 1621 Böhme wrote "De Signatura Rerum". In 1623 Böhme wrote "On Election to Grace", "On Christ's Testaments", "Mysterium Magnum", "Clavis" ("Key"). The year 1622 saw Böhme write some short works all of which were subsequently included in his first published book on New Year's Day 1624, under the title Weg zu Christo (The Way to Christ).[9][13]

The publication caused another scandal and following complaints by the clergy, Böhme was summoned to the Town Council on 26 March 1624. The report of the meeting was that:

| I must tell you, sir, that yesterday the pharisaical devil was let loose, cursed me and my little book, and condemned the book to the fire. He charged me with shocking vices; with being a scorner of both Church and Sacraments, and with getting drunk daily on brandy, wine, and beer; all of which is untrue; while he himself is a drunken man." |

| — Jacob Böhme writing about Gregorius Richter on 2 April 1624.[15] |

Böhme left for Dresden on 8 or 9 May 1624, where he stayed with the court physician for two months. In Dresden he was accepted by the nobility and high clergy. His intellect was also recognized by the professors of Dresden, who in a hearing in May 1624, encouraged Böhme to go home to his family in Görlitz.[8] During Böhme's absence his family had suffered during the Thirty Years' War.[8]

Once home, Böhme accepted an invitation to stay with Herr von Schweinitz, who had a country-seat. While there Böhme began to write his last book, the 177 Theosophic Questions. However, he fell terminally ill with a bowel complaint forcing him to travel home on 7 November. Gregorius Richter, Böhme's adversary from Görlitz, had died in August 1624, while Böhme was away. The new clergy, still wary of Böhme, forced him to answer a long list of questions when he wanted to receive the sacrament. He died on 17 November 1624.[16]

In this short period, Böhme produced an enormous amount of writing, including his major works De Signatura Rerum (The Signature of All Things) and Mysterium Magnum. He also developed a following throughout Europe, where his followers were known as Behmenists.

The son of Böhme's chief antagonist, the pastor primarius of Görlitz Gregorius Richter, edited a collection of extracts from his writings, which were afterwards published complete at Amsterdam with the help of Coenraad van Beuningen in the year 1682. Böhme's full works were first printed in 1730.

Theology[edit source]

The chief concern of Böhme's writing was the nature of sin, evil and redemption. Consistent with Lutheran theology, Böhme preached that humanity had fallen from a state of divine grace to a state of sin and suffering, that the forces of evil included fallen angels who had rebelled against God, and that God's goal was to restore the world to a state of grace.[citation needed]

There are some serious departures from accepted Lutheran theology, however, such as his rejection of sola fide, as in this passage from The Way to Christ:

Another place where Böhme may depart from accepted theology (though this was open to question due to his somewhat obscure, oracular style) was in his description of the Fall as a necessary stage in the evolution of the Universe.[18] A difficulty with his theology is the fact that he had a mystical vision, which he reinterpreted and reformulated.[18] According to F. von Ingen, to Böhme, in order to reach God, man has to go through hell first. God exists without time or space, he regenerates himself through eternity. Böhme restates the trinity as truly existing but with a novel interpretation. God, the Father is fire, who gives birth to his son, whom Böhme calls light. The Holy Spirit is the living principle, or the divine life.[19]

However, it is clear that Böhme never claimed that God sees evil as desirable, necessary or as part of divine will to bring forth good. In his Threefold Life, Böhme states: "[I]n the order of nature, an evil thing cannot produce a good thing out of itself, but one evil thing generates another." Böhme did not believe that there is any "divine mandate or metaphysically inherent necessity for evil and its effects in the scheme of things."[20] Dr. John Pordage, a commentator on Böhme, wrote that Böhme "whensoever he attributes evil to eternal nature considers it in its fallen state, as it became infected by the fall of Lucifer... ."[20] Evil is seen as "the disorder, rebellion, perversion of making spirit nature's servant",[21] which is to say a perversion of initial Divine order.

Böhme's correspondences in "Aurora" of the seven qualities, planets and humoral-elemental associations:

- 1. Dry - Saturn - melancholy, power of death;

- 2. Sweet - Jupiter - sanguine, gentle source of life;

- 3. Bitter - Mars - choleric, destructive source of life;

- 4. Fire - Sun/Moon - night/day; evil/good; sin/virtue; Moon, later = phlegmatic, watery;

- 5. Love - Venus - love of life, spiritual rebirth;

- 6. Sound - Mercury - keen spirit, illumination, expression;

- 7. Corpus - Earth - totality of forces awaiting rebirth.

In "De Tribus Principiis" or "On the Three Principles of Divine Being" Böhme subsumed the seven principles into the Trinity:

- 1. The "dark world" of the Father (Qualities 1-2-3);

- 2. The "light world" of the Holy Spirit (Qualities 5-6-7);

- 3. "This world" of Satan and Christ (Quality 4).

Cosmology[edit source]

In one interpretation of Böhme's cosmology, it was necessary for humanity to return to God, and for all original unities to undergo differentiation, desire and conflict—as in the rebellion of Satan, the separation of Eve from Adam and their acquisition of the knowledge of good and evil—in order for creation to evolve to a new state of redeemed harmony that would be more perfect than the original state of innocence, allowing God to achieve a new self-awareness by interacting with a creation that was both part of, and distinct from, Himself. Free will becomes the most important gift God gives to humanity, allowing us to seek divine grace as a deliberate choice while still allowing us to remain individuals.[citation needed]

Marian views[edit source]

Böhme believed that the Son of God became human through the Virgin Mary. Before the birth of Christ, God recognized himself as a virgin. This virgin is therefore a mirror of God's wisdom and knowledge.[19] Böhme follows Luther in that he views Mary within the context of Christ. Unlike Luther, he does not address himself to dogmatic issues very much, but to the human side of Mary. Like all other women, she was human and therefore subject to sin. Only after God elected her with his grace to become the mother of his son, did she inherit the status of sinlessness.[19] Mary did not move the Word, the Word moved Mary, so Böhme, explaining that all her grace came from Christ. Mary is "blessed among women" but not because of her qualifications, but because of her humility. Mary is an instrument of God; an example of what God can do: It shall not be forgotten in all eternity, that God became human in her.[22]

Böhme, unlike Luther, did not believe that Mary was the Ever Virgin. Her virginity after the birth of Jesus is unrealistic to Böhme. The true salvation is Christ, not Mary. The importance of Mary, a human like every one of us, is that she gave birth to Jesus Christ as a human being. If Mary had not been human, according to Böhme, Christ would be a stranger and not our brother. Christ must grow in us as he did in Mary. She became blessed by accepting Christ. In a reborn Christian, as in Mary, all that is temporal disappears and only the heavenly part remains for all eternity. Böhme's peculiar theological language, involving fire, light and spirit, which permeates his theology and Marian views, does not distract much from the fact that his basic positions are Lutheran.[22]

Influences[edit source]

Böhme's writing shows the influence of Neoplatonist and alchemical[23] writers such as Paracelsus, while remaining firmly within a Christian tradition. He has in turn greatly influenced many anti-authoritarian and mystical movements, such as Radical Pietism[24][25][26][27][28][29] (including the Ephrata Cloister[30] and Society of the Woman in the Wilderness), the Religious Society of Friends, the Philadelphians, the Gichtelians, the Harmony Society, the Zoarite Separatists, Rosicrucianism, Martinism and Christian theosophy. Böhme's disciple and mentor, the Liegnitz physician Balthasar Walther, who had travelled to the Holy Land in search of magical, kabbalistic and alchemical wisdom, also introduced kabbalistic ideas into Böhme's thought.[31] Böhme was also an important source of German Romantic philosophy, influencing Schelling in particular.[32] In Richard Bucke's 1901 treatise Cosmic Consciousness, special attention was given to the profundity of Böhme's spiritual enlightenment, which seemed to reveal to Böhme an ultimate nondifference, or nonduality, between human beings and God. Jakob Böhme's writings also had some influence on the modern theosophical movement of the Theosophical Society. Blavatsky and W.Q. Judge wrote about Jakob Böhme's philosophy.[33][34] Böhme was also an important influence on the ideas of Franz Hartmann, the founder in 1886 of the German branch of the Theosophical Society. Hartmann described the writings of Böhme as “the most valuable and useful treasure in spiritual literature.”[35]

Behmenism[edit source]

— Jacob Boehme[36]

Behmenism, also Behemenism or Boehmenism, is the English-language designation for a 17th-century European Christian movement based on the teachings of German mystic and theosopher Jakob Böhme (1575-1624). The term was not usually applied by followers of Böhme's theosophy to themselves, but rather was used by some opponents of Böhme's thought as a polemical term. The origins of the term date back to the German literature of the 1620s, when opponents of Böhme's thought, such as the Thuringian antinomian Esajas Stiefel, the Lutheran theologian Peter Widmann and others denounced the writings of Böhme and the Böhmisten. When his writings began to appear in England in the 1640s, Böhme's surname was irretrievably corrupted to the form "Behmen" or "Behemen", whence the term "Behmenism" developed.[37] A follower of Böhme's theosophy is a "Behmenist".

Behmenism does not describe the beliefs of any single formal religious sect, but instead designates a more general description of Böhme's interpretation of Christianity, when used as a source of devotional inspiration by a variety of groups. Böhme's views greatly influenced many anti-authoritarian and Christian mystical movements, such as the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), the Philadelphians,[38] the Gichtelians, the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness (led by Johannes Kelpius), the Ephrata Cloister, the Harmony Society, Martinism, and Christian theosophy. Böhme was also an important source of German Romantic philosophy, influencing Schelling and Franz von Baader in particular.[32] In Richard Bucke's 1901 treatise Cosmic Consciousness, special attention was given to the profundity of Böhme's spiritual enlightenment, which seemed to reveal to Böhme an ultimate nondifference, or nonduality, between human beings and God. Böhme is also an important influence on the ideas of the English Romantic poet, artist and mystic William Blake. After having seen the William Law edition of the works of Jakob Böhme, published between 1764–1781, in which some illustrations had been included by the German early Böhme exegetist Dionysius Andreas Freher (1649–1728), William Blake said during a dinner party in 1825 “Michel Angelo could not have surpassed them”.[39]

Despite being based on a corrupted form of Böhme's surname, the term Behmenism has retained a certain utility in modern English-language historiography, where it is still occasionally employed, although often to designate specifically English followers of Böhme's theosophy.[40] Given the transnational nature of Böhme's influence, however, the term at least implies manifold international connections between Behmenists.[41] In any case, the term is preferred to clumsier variants such as "Böhmeianism" or "Böhmism", although these may also be encountered.

Reaction[edit source]

In addition to the scientific revolution, the 17th century was a time of mystical revolution in Catholicism, Protestantism and Judaism. The Protestant revolution developed from Böhme and some medieval mystics. Böhme became important in intellectual circles in Protestant Europe, following from the publication of his books in England, Holland and Germany in the 1640s and 1650s.[42] Böhme was especially important for the Millenarians and was taken seriously by the Cambridge Platonists and Dutch Collegiants. Henry More was critical of Böhme and claimed he was not a real prophet, and had no exceptional insight into metaphysical questions. Overall, although his writings did not influence political or religious debates in England, his influence can be seen in more esoteric forms such as on alchemical experimentation, metaphysical speculation and spiritual contemplation, as well as utopian literature and the development of neologisms.[43] More, for example, dismissed Opera Posthuma by Spinoza as a return to Behmenism.[44]

While Böhme was famous in Holland, England, France, Denmark and America during the 17th century, he became less influential during the 18th century. A revival, however, occurred late in that century with interest from German Romantics, who considered Böhme a forerunner to the movement. Poets such as John Milton, Ludwig Tieck, Novalis, William Blake[45] and W. B. Yeats[46] found inspiration in Böhme's writings. Coleridge, in his Biographia Literaria, speaks of Böhme with admiration. Böhme was highly thought of by the German philosophers Baader, Schelling and Schopenhauer. Hegel went as far as to say that Böhme was "the first German philosopher".[47] Danish Bishop Hans Lassen Martensen published a book about Böhme.[48]

Several authors have found Boehme's description of the three original Principles and the seven Spirits to be similar to the Law of Three and the Law of Seven described in the works of Boris Mouravieff and George Gurdjieff.[49][50]

Works[edit source]

- Aurora: Die Morgenröte im Aufgang (unfinished) (1612)

- De Tribus Principiis (The Three Principles of the Divine Essence, 1618–1619)

- The Threefold Life of Man (1620)

- Answers to Forty Questions Concerning the Soul (1620)

- The Treatise of the Incarnations: (1620)

- I. Of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ

- II. Of the Suffering, Dying, Death and Resurrection of Christ

- III. Of the Tree of Faith

- The Great Six Points (1620)

- Of the Earthly and of the Heavenly Mystery (1620)

- Of the Last Times (1620)

- De Signatura Rerum (The Signature of All Things, 1621)

- The Four Complexions (1621)

- Of True Repentance (1622)

- Of True Resignation (1622)

- Of Regeneration (1622)

- Of Predestination (1623)

- A Short Compendium of Repentance (1623)

- The Mysterium Magnum (1623)

- A Table of the Divine Manifestation, or an Exposition of the Threefold World (1623)

- The Supersensual Life (1624)

- Of Divine Contemplation or Vision (unfinished) (1624)

- Of Christ's Testaments (1624)

- I. Baptism

- II. The Supper

- Of Illumination (1624)

- 177 Theosophic Questions, with Answers to Thirteen of Them (unfinished) (1624)

- An Epitome of the Mysterium Magnum (1624)

- The Holy Week or a Prayer Book (unfinished) (1624)

- A Table of the Three Principles (1624)

- Of the Last Judgement (lost) (1624)

- The Clavis (1624)

- Sixty-two Theosophic Epistles (1618–1624)

Books in print[edit source]

- The Way to Christ (inc. True Repentance, True Resignation, Regeneration or the New Birth, The Supersensual Life, Of Heaven & Hell, The Way from Darkness to True Illumination) edited by William Law, Diggory Press ISBN 978-1-84685-791-1

- Of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ, translated from the German by John Rolleston Earle, London, Constable and Company LTD, 1934.

See also[edit source]

Notes[edit source]

- ^ Mills 2002, p. 16

- ^ "Böhme". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Sar Perserverando, Grand Master (2015). An anthology for Martinists. The Hermetic Order of Martinists. p. 3.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica - Jakob Böhme

- ^ Jaqua, Mark (1984). "The Illumination of Jacob Boehme" (PDF). TAT Journal. TAT Foundation. 13. HTML version

- ^ Jacob Böhme: The Teutonic Philosopher. 24th Convocation of Ontario College Monday April 5, 2004. 2004.

- ^ a b c Deussen 1910, p. xxxviii

- ^ a b c d

Debelius, F.W. (1908). "Boehme, Jakob". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. 2 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 209–211.

Debelius, F.W. (1908). "Boehme, Jakob". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. 2 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 209–211. - ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 114.

- ^ Martensen 1885, p. 13

- ^ Deussen 1910, pp. xli-xlii

- ^ Weeks 1991, p. 2

- ^ https://jesus.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/the-way-to-christ.pdf

- ^ Deussen 1910, p. xlviii

- ^ Deussen 1910, pp. xlviii-xlix

- ^ Deussen 1910, pp. xlix-l

- ^ "The Way to Christ". Pass the Word Services.

- ^ a b von Ingen 1988, p. 517.

- ^ a b c von Ingen 1988, p. 518.

- ^ a b Musès, Charles A. Illumination on Jakob Böhme. New York: King's Crown Press, 1951

- ^ Stoudt, John Joseph. Jakob Böhme: His Life and Thought. New York: The Seabury Press, 1968

- ^ a b von Ingen 1988, p. 519.

- ^ In several works he used alchemical principles and symbols without hesitation to demonstrate theological realities. Borrowing alchemical terminology in order to explain religious and mystical frameworks, Böhme assumed that alchemical language is not only a metaphor for laboratory research. Alchemy is a metaphysical science because he understood that matter is contaminated with spirit. Calian 2010, p.184.

- ^ Brown 1996.

- ^ Durnbaugh 2001.

- ^ Ensign 1955.

- ^ Hirsch 1951.

- ^ Stoeffler 1965.

- ^ Stoeffler 1973.

- ^ Brumbaugh 1899, p. 443.

- ^ See Leigh T.I. Penman, ‘A Second Christian Rosencreuz? Jacob Boehme's Disciple Balthasar Walther (1558-c.1630) and the Kabbalah. With a Bibliography of Walther's Printed Works.’ Western Esotericism. Selected Papers Read at the Symposium on Western Esotericism held at Åbo, Finland, on 15–17 August 2007. (Scripta instituti donneriani Aboensis, XX). T. Ahlbäck, ed. Åbo, Finland: Donner Institute, 2008: 154-172.

- ^ a b See Schopenhauer's On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, Ch II, 8

- ^ Theosophy, Imagination, Tradition: Studies in Western Esotericism by A. Faivre. 28.

- ^ “Theosophical Articles”, William Q. Judge, Theosophy Co., Los Angeles, 1980, volume I, p. 271. The title of the article is “Jacob Boehme and the Secret Doctrine”.

- ^ A. Versluis, Magic and Mysticism, 2007.

- ^ Faivre 2000, p. 13.

- ^ An early English language example is provided in Anderdon, John. "One blow at Babel, in those of the People called Behmenites, Whose foundation is...upon their own cardinal conception, begotten in their imaginations upon Jacob Behmen's writings." London: 1662.

- ^ Hutin, Serge. "The Behmenists and the Philadelphian Society". The Jacob Boehme Society Quarterly 1:5 (Autumn 1953): 5-11.

- ^ The Spiritual Side of Samuel Richardson, Mysticism, Behmenism and Millenarianism in an Eighteenth-Century English Novelist, Gerda J. Joling-van der Sar, 2003, p. 140.[1]

- ^ See for example B. J. Gibbons, Gender in mystical and occult thought: Behmenism and its development in England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- ^ Thune, Nils. The Behemenists and the Philadelphians: A contribution to the study of English mysticism in the 17th and 18th centuries. Uppsala: Almquist and Wiksells, 1948.

- ^ Popkin 1998, pp. 401-402

- ^ All of Böhme’s treatises and most of his letters were translated into English (as well as two pamphlets that were translated into Welsh by the Parliamentarian evangelist Morgan Llwyd) between 1645 and 1662.

Hessayon, Ariel (2013). Jacob Boehme’s writings during the English Revolution and afterwards: their publication, dissemination and influence in An Introduction to Jacob Boehme: Four Centuries of Thought and Reception, Routledge, Eds Hessayon, Ariel and Apetrei, Sarah. pp.77–97. - ^ Popkin 1998, p. 402

- ^ The influence of Jacob Boehme on the work of William Blake

- ^ Affinities between William Butler Yeats and Jacob Boehme.

- ^ Weeks 1991, pp. 2–3

- ^ Jacob Boehme: his life and teaching. Or Studies in theosophy

- ^ Nicolescu 1998, p. 47.

- ^ Bourgeault 2013.

References[edit source]

- Bailey, Margaret Lewis (1914). Milton and Jakob Boehme; a study of German mysticism in seventeenth-century England. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bourgeault, Cynthia (2013). The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three: Discovering the Radical Truth at the Heart of Christianity. Shambhala. ISBN 978-0-8348-2894-0. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Brown, Dale W. (1996). Understanding Pietism.

- Brumbaugh, Martin Grove (1899). A History of the German Baptist Brethren in Europe and America. Brethren publishing house. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Calian, George-Florin (2010). Alkimia Operativa and Alkimia Speculativa. Some Modern Controversies on the Historiography of Alchemy. Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU.

- Deussen, Paul (1910). "Introduction". In Boehme, Jacob (ed.). Concerning the three principles of the divine essence. London: John M. Watkins.

- Durnbaugh, Donald F. (2001). "Pennsylvania's Crazy Quilt of German Religious Groups". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 68 (1): 8–30.

- Ensign, Chauncey David (1955). Radical German Pietism (c. 1675-c. 1760) (Thesis). Boston University. hdl:2144/8771.

- Hirsch, Emanuel (1951). Geschichte der Neueren Evangelischen Theologie in Zusammenhang mit den allgemeinen Bewegungen des europaischen Denkens. Volume II. Gutersloh: c. Bertelsmann Verlag. p. 209, 255, 256.

- Mills, Jon (2002). The Unconscious Abyss: Hegel's Anticipation of Psychoanalysis. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Martensen, Hans Lassen (1885). Jacob Boehme: his life and teaching, or Studies in theosophy. trans. T. Rhys Evans. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Nicolescu, Basarab (1998). "Gurdjieff's philosophy of nature". In Needleman, J.; Baker, G. (eds.). Gurdjieff: Essays and Reflections on the Man and His Teachings. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 37–69. ISBN 978-1-4411-1084-8. Retrieved 23 July 2017. A revised version is available: "Gurdjieff's philosophy of nature" (PDF). 2003. p. 12. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Popkin, Richard (1998). "The religious background of seventeenth-century philosophy". In Garber, Daniel; Ayers, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Philosophy. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53720-9.

- Stoeffler, F. Ernest (1965). The Rise of Evangelical Pietism. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Stoeffler, F. Ernest (1973). German Pietism During the Eighteenth Century. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Swainson, William Perkes (1921). Jacob Boehme; the Teutonic philosopher. London: William Rider & Son, Ltd.

- von Ingen, F. (1988). Jacob Böhme in Marienlexikon. Eos: St. Ottilien.

- Weeks, Andrew (1991). Boehme: An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher and Mystic. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0596-3.

External links[edit source]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jakob Böhme |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Jakob Böhme |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jakob Böhme. |

- Works by Jakob Böhme at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jakob Böhme at Internet Archive

- Works by Jakob Böhme at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Jacob Boehme Online

- The Life and the Doctrines of Jacob Boehme, by Franz Hartmann

- The Correspondence of Jakob Böhme in EMLO

- Jacob Boehme Resources

- Large electronic text archive of Jacob Boehme in English

- The Way to Christ in English translation

- A Modern Gnostic from Paul Carus' History of the Devil (1900).

- Boehme: The Ungrund and Freedom, by Nikolai Berdyaev

- Boehme: The Teaching about Sophia, by Nikolai Berdyaev

- The Writings of Jane Lead, Christian Mystic, Prolific visionary writer and follower of Jacob Boehme.

- 1575 births

- 1624 deaths

- 16th-century alchemists

- 16th-century Christian mystics

- 16th-century German theologians

- 16th-century German Protestant theologians

- 17th-century alchemists

- 17th-century Christian mystics

- 17th-century German writers

- 17th-century German Protestant theologians

- Christian occultists

- Christian philosophers

- Epistemologists

- German alchemists

- German Lutheran theologians

- German male poets

- German philosophers

- Lutheran pacifists

- Lutheran poets

- Martinism

- Metaphysicians

- Mystics

- Ontologists

- People from Zgorzelec County

- Philosophers of religion

- Protestant mystics

- Protestant views on Mary

조현 기자

조현 기자 원본보기2020 도쿄올림픽을 닷새 앞둔 7월18일 도쿄 하루미 지역 올림픽선수촌 인근 도로에서 극우단체가 차량을 이용해 확성기 시위를 하고 있다. 도쿄/올림픽사진공동취재단

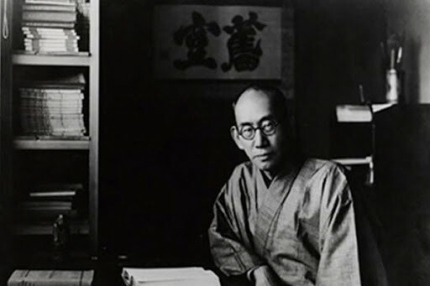

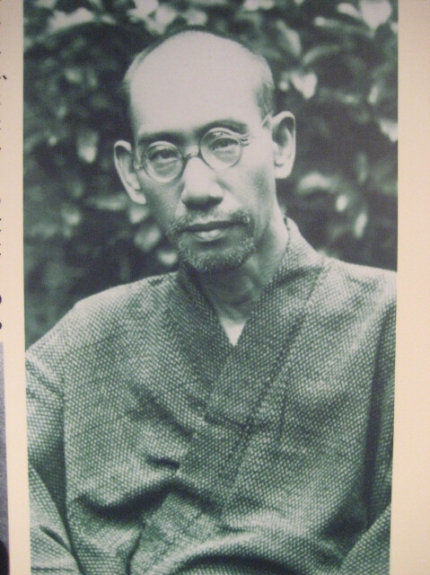

원본보기2020 도쿄올림픽을 닷새 앞둔 7월18일 도쿄 하루미 지역 올림픽선수촌 인근 도로에서 극우단체가 차량을 이용해 확성기 시위를 하고 있다. 도쿄/올림픽사진공동취재단 원본보기니시다 기타로. <한겨레> 자료사진

원본보기니시다 기타로. <한겨레> 자료사진 원본보기교토학파의 아버지인 니시다 기타로가 고뇌하며 걷던 ‘철학의 길’이 시작되는 일본 교토의 은각사 전경. 조현 기자

원본보기교토학파의 아버지인 니시다 기타로가 고뇌하며 걷던 ‘철학의 길’이 시작되는 일본 교토의 은각사 전경. 조현 기자 니시다 기타로. <한겨레> 자료사진

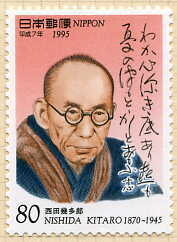

니시다 기타로. <한겨레> 자료사진 일본에서 발행된 니시다 기타로 기념우표.

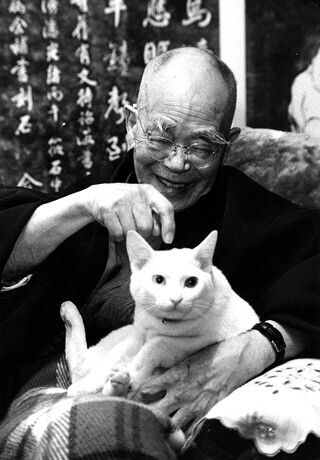

일본에서 발행된 니시다 기타로 기념우표. 스즈키 다이세쓰. <한겨레> 자료사진

스즈키 다이세쓰. <한겨레> 자료사진 원본보기1946년 도쿄 전범재판석에 앉은 도조 히데키(맨 왼쪽) 등 일본군 전범들. 수많은 부하들과 민간인을 죽음으로 몰아넣은 그들 중 다수가 아무 책임도 지지 않고 다시 출셋길을 걸었다. <한겨레> 자료사진

원본보기1946년 도쿄 전범재판석에 앉은 도조 히데키(맨 왼쪽) 등 일본군 전범들. 수많은 부하들과 민간인을 죽음으로 몰아넣은 그들 중 다수가 아무 책임도 지지 않고 다시 출셋길을 걸었다. <한겨레> 자료사진