Gayatri Mantra

The Gāyatrī Mantra (Sanskrit pronunciation: [ɡaː.jɐ.triː.mɐn.trɐ.]), also known as the Sāvitri Mantra (Sanskrit pronunciation: [saː.vi.triː.mɐn.trɐ.]), is a sacred mantra from the Rig Veda (Mandala 3.62.10),[1] dedicated to the Vedic deity Savitr.[1][2] It is known as "Mother of the Vedas".[3]

The term Gāyatrī may also refer to a type of mantra which follows the same Vedic meter as the original Gāyatrī Mantra. There are many such Gāyatrīs for various gods and goddesses.[3] Furthermore, Gāyatrī is the name of the Goddess of the mantra and the meter.[4]

The Gayatri mantra is cited widely in Hindu texts, such as the mantra listings of the Śrauta liturgy, and classical Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita,[5][6] Harivamsa,[7] and Manusmṛti.[8] The mantra and its associated metric form was known by the Buddha.[9] The mantra is an important part of the upanayana ceremony. Modern Hindu reform movements spread the practice of the mantra to everyone and its use is now very widespread.[10][11]

Text[edit]

The main mantra appears in the hymn RV 3.62.10. During its recitation, the hymn is preceded by oṃ (ॐ) and the formula bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ (भूर् भुवः स्वः), known as the mahāvyāhṛti, or "great (mystical) utterance". This prefixing of the mantra is properly described in the Taittiriya Aranyaka (2.11.1-8), which states that it should be chanted with the syllable oṃ, followed by the three Vyahrtis and the Gayatri verse.[12]

Whereas in principle the gāyatrī mantra specifies three pādas of eight syllables each, the text of the verse as preserved in the Samhita is one short, seven instead of eight. Metrical restoration would emend the attested tri-syllabic vareṇyaṃ with a tetra-syllabic vareṇiyaṃ.[13]

The Gayatri mantra with svaras is,[12] in Devanagari:

- ॐ भूर्भुव॒ स्सुवः॑

तत्स॑ वि॒तुर्वरे᳚ण्यं॒

भर्गो॑ दे॒वस्य॑ धीमहि

धियो॒ यो नः॑ प्रचो॒दया᳚त् ॥

In IAST:

- oṃ bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ

- tat savitur vareṇyaṃ

- bhargo devasya dhīmahi

- dhiyo yo naḥ pracodayāt

- – Rigveda 3.62.10[14]

Dedication[edit]

The Gāyatrī mantra is dedicated to Savitṛ, a solar deity. The mantra is attributed to the much revered sage Vishvamitra, who is also considered the author of Mandala 3 of the Rigveda. Many monotheistic sects of Hinduism such as Arya Samaj hold that the Gayatri mantra is in praise of One Supreme Creator known by the name Om as mentioned in the Yajurveda, 40:17.[15][16]

Translations[edit]

The Gayatri mantra has been translated in many ways.[note 1] Quite literal translations include:

- Swami Vivekananda: "We meditate on the glory of that Being who has produced this universe; may She enlighten our minds."[17]

- Monier Monier-Williams (1882): "Let us meditate on that excellent glory of the divine vivifying Sun, May he enlighten our understandings."[18][19]

- Ralph T.H. Griffith (1896): "May we attain that excellent glory of Savitar the god: So may He stimulate our prayers."[20]

- S. Radhakrishnan:

- Sri Aurobindo: "We choose the Supreme Light of the divine Sun; we aspire that it may impel our minds."[23] Sri Aurobindo further elaborates: "The Sun is the symbol of divine Light that is coming down and Gayatri gives expression to the aspiration asking that divine Light to come down and give impulsion to all the activities of the mind."[23]

- Sri Chinmoy: " We meditate on the Transcendental Glory of the Deity Supreme,Who is inside the Heart of the Earth, inside the Life of the Sky and inside the Soul of the Heaven. May He stimulate and illume our minds.".

- Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton: "Might we make our own that desirable effulgence of god Savitar, who will rouse forth our insights."[24]

Literal translations of the words are below:

- Om - The sacred syllable, pranava;

- Bhur - Bhuloka (physical plane);

- Bhuvah - Antariksha (space);

- Suvah - Svarga (Heaven);

- Tat - Paramatma (Supreme Soul);

- Savitur - Ishvara (Surya) (Sun god);

- Varenyam - Fit to be worshipped;

- Bhargo - Remover of sins and ignorance;

- Devasya - Glory (Jnana Svarupa i.e. feminine/female);

- Dhimahi - We meditate;

- Dhiyo - Buddhi (Intellect);

- Yo - Which;

- Nah - Our;

- Prachodayat: Enlighten/inspire.[dubious ]

More interpretative translations include:

- Sir John Woodroffe (Arthur Avalon) (1913): "Om. Let us contemplate the wondrous spirit of the Divine Creator (Savitri) of the earthly, atmospheric, and celestial spheres. May He direct our minds (that is, 'towards' the attainment of dharmma, artha, kama, and moksha), Om."[25]

- Ravi Shankar (poet): "Oh manifest and unmanifest, wave and ray of breath, red lotus of insight, transfix us from eye to navel to throat, under canopy of stars spring from soil in an unbroken arc of light that we might immerse ourselves until lit from within like the sun itself."[26]

- Shriram Sharma: Om, the Brahm, the Universal Divine Energy, vital spiritual energy (Pran), the essence of our life existence, Positivity, destroyer of sufferings, the happiness, that is bright, luminous like the Sun, best, destroyer of evil thoughts, the divinity who grants happiness may imbibe its Divinity and Brilliance within us which may purify us and guide our righteous wisdom on the right path.[27]

- Sir William Jones (1807): "Let us adore the supremacy of that divine sun, the god-head who illuminates all, who recreates all, from whom all proceed, to whom all must return, whom we invoke to direct our understandings right in our progress toward his holy seat."[28]

- William Quan Judge (1893): "Unveil, O Thou who givest sustenance to the Universe, from whom all proceed, to whom all must return, that face of the True Sun now hidden by a vase of golden light, that we may see the truth and do our whole duty on our journey to thy sacred seat."[29]

- Sivanath Sastri (Brahmo Samaj) (1911): "We meditate on the worshipable power and glory of Him who has created the earth, the nether world and the heavens (i.e. the universe), and who directs our understanding."[30][note 2]

- Swami Sivananda: "Let us meditate on Isvara and His Glory who has created the Universe, who is fit to be worshipped, who is the remover of all sins and ignorance. May he enlighten our intellect."

- Maharshi Dayananda Saraswati (founder of Arya Samaj): "Oh God! Thou art the Giver of Life, Remover of pain and sorrow, The Bestower of happiness. Oh! Creator of the Universe, May we receive thy supreme sin-destroying light, May Thou guide our intellect in the right direction."[31]

- Kirpal Singh: "Muttering the sacred syllable 'Aum' rise above the three regions, And turn thy attention to the All-Absorbing Sun within. Accepting its influence be thou absorbed in the Sun, And it shall in its own likeness make thee All-Luminous."[32]

Syllables of the Gayatri mantra[edit]

Gayatri meter, called Gayatri Chandas in Sanskrit, is twenty-four syllables comprising three lines (Sk. padas, literally "feet") of eight syllables each. The Gayatri mantra as received is short one syllable in the first line: tat sa vi tur va reṇ yaṃ. Being only twenty-three syllables the Gayatri mantra is Nichruth Gayatri Chandas ("Gayatri meter short by one syllable").[citation needed]A reconstruction of vareṇyaṃ to a proposed historical vareṇiyaṃ restores the first line to eight syllables. In practise, people reciting the mantra may retain seven syllables and simply prolong the length of time they pronounce the "m", they may append an extra syllable of "mmm" (approximately va-ren-yam-mmm), or they may use the reconstructed vareṇiyaṃ.[citation needed]

Textual appearances[edit]

Hindu literature[edit]

The Gayatri mantra is cited widely in Hindu texts, such as the mantra listings of the Śrauta liturgy,[note 3][note 4] and cited several times in the Brahmanams and the Srauta-sutras.[note 5][note 6] It is also cited in a number of grhyasutras, mostly in connection with the upanayana ceremony[35] in which it has a significant role[citation needed].

The Gayatri mantra is the subject of esoteric treatment and explanation in some major Upanishads, including Mukhya Upanishads such as the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad,[note 7] the Shvetashvatara Upanishad[note 8] and the Maitrayaniya Upanishad;[note 9] as well as other well-known works such as the Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana.[note 10] The text also appears in minor Upanishads, such as the Surya Upanishad.[citation needed]

The Gayatri mantra is the apparent inspiration for derivative "gāyatrī" stanzas dedicated to other deities[citation needed]. Those derivations are patterned on the formula vidmahe - dhīmahi - pracodayāt",[36] and have been interpolated[37] into some recensions of the Shatarudriya litany.[note 11] Gāyatrīs of this form are also found in the Mahanarayana Upanishad.[note 12]

The Gayatri mantra is also repeated and cited widely in Hindu texts such as the Mahabharata[citation needed], Harivamsa,[7] and Manusmṛti. [8]

Buddhist corpus[edit]

In Majjhima Nikaya 92, the Buddha refers to the Sāvitri (Pali: sāvittī) mantra as the foremost meter, in the same sense as the king is foremost among humans, or the sun is foremost among lights:

In Sutta Nipata 3.4, the Buddha uses the Sāvitri mantra as a paradigmatic indicator of Brahmanic knowledge:

Upanayana ceremony[edit]

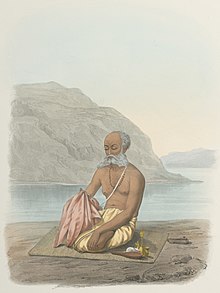

Imparting the Gayatri mantra to young Hindu men is an important part of the traditional upanayana ceremony[citation needed], which marks the beginning of study of the Vedas. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan described this as the essence of the ceremony,[21] which is sometimes called "Gayatri diksha", i.e. initiation into the Gayatri mantra.[40] However, traditionally, the stanza RV.3.62.10 is imparted only to Brahmana[citation needed]. Other Gayatri verses are used in the upanayana ceremony are: RV.1.35.2, in the tristubh meter, for a kshatriya and either RV.1.35.9 or RV.4.40.5 in the jagati meter for a Vaishya.[41]

Mantra-recitation[edit]

Gayatri japa is used as a method of prāyaścitta (atonement)[citation needed]. It is believed by practitioners that reciting the mantra bestows wisdom and enlightenment, through the vehicle of the Sun (Savitr), who represents the source and inspiration of the universe.[21]

Brahmo Samaj[edit]

In 1827 Ram Mohan Roy published a dissertation on the Gayatri mantra[42] that analysed it in the context of various Upanishads. Roy prescribed a Brahmin to always pronounce om at the beginning and end of the Gayatri mantra.[43] From 1830, the Gayatri mantra was used for private devotion of Brahmos[citation needed]. In 1843, the First Covenant of Brahmo Samaj required the Gayatri mantra for Divine Worship[citation needed]. From 1848-1850 with the rejection of Vedas, the Adi Dharma Brahmins use the Gayatri mantra in their private devotions.[44]

Hindu revivalism[edit]

In the later 19th century, Hindu reform movements spread the chanting of the Gayatri mantra.[citation needed] In 1898 for example, Swami Vivekananda claimed that, according to the Vedas and the Bhagavad Gita, a person became Brahmana through learning from his Guru, and not because of birth[citation needed]. He administered the sacred thread ceremony and the Gayatri mantra to non-Brahmins in Ramakrishna Mission.[45] This Hindu mantra has been popularized to the masses, pendants, audio recordings and mock scrolls.[46] Various Gayatri yajñas organised by All World Gayatri Pariwar at small and large scales in late twentieth century also helped spread Gayatri mantra to the masses.[47]

Indonesian Hinduism[edit]

The Gayatri Mantra forms the first of seven sections of the Trisandhyā Puja (Sanskrit for "three divisions"), a prayer used by the Balinese Hindus and many Hindus in Indonesia. It is uttered three times each day: 6 am at morning, noon, and 6 pm at evening.[48][49]

Popular culture[edit]

- George Harrison (The Beatles): on the life-size statue representing him, unveiled in 2015 in Liverpool, the Gayatri mantra engraved on the belt, to symbolize a landmark event in his life (see picture).

- A version of the Gayatri mantra is featured in the opening theme song of the TV series Battlestar Galactica (2004).[50]

- A variation on the William Quan Judge translation is also used as the introduction to Kate Bush's song "Lily" on her 1993 album, The Red Shoes.[citation needed]

- Cher, the singer/actress, in her Living Proof: The Farewell Tour, in 2002-2005, sang Gayatri mantra while riding a mechanical elephant. She later reprised the performance during her Classic Cher concert residency in 2017-2020 and Here We Go Again Tour in 2018-2020 (see picture).

- The Swiss avantgarde black metal band Schammasch adapted the mantra as the outro in their song "The Empyrean" on their last album "Triangle" as a Gregorian chant.[51]

- The film Mohabbatein (2000) directed by Aditya Chopra which came under controversy when Amitabh Bachchan recited the sacred Gayatri Mantra with his shoes on leading some Vedic scholars in Varanasi to complain that it insulted Hinduism[52]

- In the game Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak (2016), Gayatri Mantra can be heard being sung during the destruction of Gaalsien flagship, Hand of Sajuuk, in the final mission of campaign, Khar-Toba.[citation needed]

- The HBO show The White Lotus (2021) features a character singing a version of the Gayatri Mantra multiple times throughout the first season.[citation needed]

Other Gāyatrī Mantras[edit]

The term Gāyatrī is also a class of mantra which follows the same Vedic meter as the classic Gāyatrī Mantra. Though the classic Gāyatrī is the most famous, there are also many other Gāyatrī mantras associated with various Hindu gods and goddesses.[3]

Some examples include:[53]

Vishnu Gayatri:

Krishna Gayatri:

Shiva Gayatri:

Ganesha Gayatri:

Durga Gayatri:

Saraswati Gayatri:

Lakshmi Gayatri:

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ A literal translation of

tát savitúr váreṇ(i)yaṃ

bhárgo devásya dhīmahi

dhíyo yó naḥ pracodayāt

is as follows:- tat - that

- savitur - from savitr̥, 'that which gives birth', 'the power inside the Sun' or the Sun itself

- vareṇiyaṁ - to choose, to select; the most choosable, the best

- bhargoḥ- to be luminous, the self-luminous one

- devasya - luminous/ radiant, the divine.

- tatsavitur devasya - "of that divine entity called Savitṛ"

- dhīmahi - whose wisdom and knowledge flow, like waters

- dhiyoḥ - intellect, a faculty of the spirit inside the body, life activity

- yoḥ - which

- naḥ - our, of us

- pracodayāt - to move in a specific direction.

- cod - to move (something/somebody) in a specific direction.hina

- pra - the prefix "forth, forward."

- pracud - "to move (something/somebody) forward"

- prachodayāt - "may it move (something/somebody) forward"; inspires

- ^ The word Savitr in the original Sanskrit may be interpreted in two ways, first as the sun, secondly as the "originator or creator". Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Maharshi Debendranath Tagore used that word in the second sense. Interpreted in their way the whole formula may be thus rendered.

- ^ Sama Veda: 2.812; Vajasenayi Samhita (M): 3.35, 22.9, 30.2, 36.3; Taittiriya Samhita: 1.5.6.4, 1.5.8.4, 4.1.11.1; Maitrayani Samhita: 4.10.3; Taittiriya Aranyaka: 1.11.2

- ^ Where it is used without any special distinction, typically as one among several stanzas dedicated to Savitar at appropriate points in the various rituals.

- ^ Aitareya Brahmana: 4.32.2, 5.5.6, 5.13.8, 5.19.8; Kausitaki Brahmana: 23.3, 26.10; Asvalayana Srautasutra: 7.6.6, 8.1.18; Shankhayana Srautasutra: 2.10.2, 2.12.7, 5.5.2, 10.6.17, 10.9.16; Apastambha Srautasutra: 6.18.1

- ^ In this corpus, there is only one instance of the stanza being prefixed with the three mahavyahrtis.[33] This is in a late supplementary chapter of the Shukla Yajurveda samhita, listing the mantras used in the preliminaries to the pravargya ceremony. However, none of the parallel texts of the pravargya rite in other samhitas have the stanza at all. A form of the mantra with all seven vyahrtis prefixed is found in the last book of the Taittiriya Aranyaka, better known as the Mahanarayana Upanishad.[34] It is as follows:

ओम् भूः ओम् भुवः ओम् सुवः ओम् महः ओम् जनः ओम् तपः ओम् स॒त्यम्। ओम् तत्स॑वि॒तुर्वरे॑ण्य॒म् भर्गो॑ दे॒वस्य॑ धीमहि।

धियो॒ यो नः॑ प्रचो॒दया॑त्।

ओमापो॒ ज्योती॒ रसो॒ऽमृतं॒ ब्रह्म॒ भूर्भुव॒स्सुव॒रोम्। - ^ 6.3.6 in the well-known Kanva recension, numbered 6.3.11-13 in the Madhyamdina recension.

- ^ 4.18

- ^ 6.7, 6.34, albeit in a section known to be of late origin.

- ^ 4.28.1

- ^ Maitrayani Samhita: 2.9.1; Kathaka Samhita: 17.11

- ^ Taittiriya Aranyaka: 10.1.5-7

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Rig Veda: Rig-Veda, Book 3: HYMN LXII. Indra and Others". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Gayatri Mantra". OSME.

- ^ a b c Swami Vishnu Devananda, Vishnu Devananda (1999). Meditation and Mantras, p. 76. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- ^ Staal, Frits (June 1986). "The sound of religion". Numen. 33 (Fasc. 1): 33–64. doi:10.1163/156852786X00084. JSTOR 3270126.

- ^ Rahman 2005, p. 300.

- ^ Radhakrishnan 1994, p. 266.

- ^ a b Vedas 2003, p. 15–16.

- ^ a b Dutt 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Shults, Brett (May 2014). "On the Buddha's Use of Some Brahmanical Motifs in Pali Texts". Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. 6: 119.

- ^ Rinehart 2004, p. 127.

- ^ Lipner 1994, p. 53.

- ^ a b Carpenter, David Bailey; Whicher, Ian (2003). Yoga: the Indian tradition. London: Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 0-7007-1288-7.

- ^ B. van Nooten and G. Holland, Rig Veda. A metrically restored text. Cambridge: Harvard Oriental Series (1994).[1] Archived 8 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guy L. Beck (2006). Sacred Sound: Experiencing Music in World Religions. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-88920-421-8.

- ^ Constance Jones,James D. Ryan (2005), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, p.167, entry "Gayatri Mantra"

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2010), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books India, p.328, entry "Savitr, god"

- ^ Vivekananda, Swami (1915). The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Advaita Ashram. p. 211.

- ^ Monier Monier-Williams (1882). The Place which the Ṛig-veda Occupies in the Sandhyâ, and Other Daily Religious Services of the Hindus. Berlin: A. Asher & Company. p. 164.

- ^ Forrest Morgan, ed. (1904). The Bibliophile Library of Literature, Art and Rare Manuscripts. Vol. 1. et al. New York: The International Bibliophile Society. p. 14.

- ^ Griffith, Ralph T. H. (1890). The Hymns of the Rigveda. E.J. Lazarus. p. 87.

- ^ a b c Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (1947). Religion and Society. Read Books. p. 135. ISBN 9781406748956.

- ^ S. Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads, (1953), p. 299

- ^ a b Evening talks with Sri Aurobindo (4th rev. ed.). Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Publication Dept. 2007. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-81-7058-865-8.

- ^ Stephanie Jamison (2015). The Rigveda –– Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 554. ISBN 978-0190633394.

- ^ Woodroffe, John (1972). Tantra of the Great Liberation (Mahānirvāna Tantra). Dover Publications, Inc. p. xc.

- ^ Shankar, Ravi (January 2021). "GAYATRI MANTRA".

- ^ Sharma, Shriram. Meditation on Gayatri mantra. AWGP Organization.

- ^ Jones, William (1807). The works of Sir William Jones. Vol. 13. J. Stockdale and J. Walker. p. 367.

- ^ Judge Quan, William (January 1893). "A COMMENTARY ON THE GAYATRI". The Path. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010.

- ^ Appendix "C", Sivanath Sastri "History of the Brahmo Samaj" 1911/1912 1st edn. page XVI, publ. Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, 211 Cornwallis St. Calcutta, read : "History Of The Brahmo Samaj Vol. 1 : Sastri, Sivanath-Internet Archive". 1911.. Retrieved on 23 November 2020.

- ^ "MEDITATING ON GAYATRI MANTRA".

- ^ Singh, Kirpal (1961). The Crown of Life (PDF). p. 275.

- ^ VSM.36.3

- ^ Dravida recension: 27.1; Andhra recension: 35.1; Atharva recension: 15.2

- ^ Shankhayana grhyasutra: 2.5.12, 2.7.19; Khadira grhyasutra: 2.4.21; Apastambha grhyasutra: 4.10.9-12; Varaha grhyasutra: 5.26

- ^ Ravi Varma(1956), p.460f, Gonda(1963) p.292

- ^ Keith, Vol I. p.lxxxi

- ^ Bikkhu, Sujato (2018). Majjhima Nikaya translated by Bhikkhu Sujato.

- ^ Mills, Laurence (2020). To Sundarika-Bhāradvāja on Offerings.

- ^ Wayman, Alex (1965). "Climactic Times in Indian Mythology and Religion". History of Religions. 4 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 295–318. doi:10.1086/462508. JSTOR 1061961. S2CID 161923240.

- ^ This is on the authority of the Shankhayana Grhyasutra, 2.5.4-7 and 2.7.10. J. Gonda, "The Indian mantra", Oriens, Vol. 16, (31 December 1963), p. 285

- ^ Title of the text was Prescript for offering supreme worship by means of the Gayutree, the most sacred of the Veds. Roy, Rammohun (1832). Translation of Several Principal Books, Passages and Texts of the Veds, and of Some Controversial Works on Brahmunical Theology: and of some controversial works on Brahmunical theology. Parbury, Allen, & co. p. 109.

- ^ Roy, Ram Mohan (1901). Prescript for offering supreme worship by means of the Gayutree, the most sacred of the Veds. Kuntaline press.

So, at the end of the Gayutree, the utterance of the letter Om is commanded by the sacred passage cited by Goonu-Vishnoo 'A Brahman shall in every instance pronounce Om, at the beginning and at the end; for unless the letter Om precede, the desirable consequence will fail; and unless it follow, it will not be long retained.'

- ^ Sivanath Sastri "History of the Brahmo Samaj" 1911/1912 1st edn. publ. Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, 211 Cornwallis St. Calcutta

- ^ Mitra, S. S. (2001). Bengal's Renaissance. Academic Publishers. p. 71. ISBN 978-81-87504-18-4.

- ^ Bakhle, Janaki (2005). Two men and music: nationalism in the making of an Indian classical tradition. Oxford University Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-19-516610-1.

- ^ Pandya, Dr. Pranav (2001). Reviving the Vedic Culture of Yagya. Vedmata Gayatri Trust. pp. 25–28.

- ^ Island Secrets: Stories of Love, Lust and Loss in Bali

- ^ Renegotiating Boundaries: Local Politics in Post-Suharto Indonesia

- ^ Battlestar Galactica's Cylon Dream Kit

- ^ "Analysis: Schammasch - "Triangle"". Metal Lifestyle. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Amitabh Bachchan in Hot Water Over Gayatri Mantra with Shoes". Hinduism Tonday. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Swami Vishnu Devananda, Vishnu Devananda (1999). Meditation and Mantras, pp. 76-77. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

Sources[edit]

- Bloomfield, Maurice (1906). A Vedic Concordance: Being an Alphabetic Index to Every Line of Every Stanza of the Published Vedic Literature and to the Liturgical Formulas Thereof; that Is, an Index to the Vedic Mantras, Together with an Account of Their Variations in the Different Vedic Books. Harvard university. ISBN 9788120806542.

- Dutt, Manmatha Nath (1 March 2006). The Dharma Sastra Or the Hindu Law Codes. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4254-8964-9.

- Lipner, Julius J. (1994). Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-05181-1.

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (1994). The Bhagavadgita: With an Introductory Essay, Sanskrit Text, English Translation, and Notes. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-81-7223-087-6.

- Rahman, M. M. (1 January 2005). Encyclopaedia of Historiography. Anmol Publications Pvt. Limited. ISBN 978-81-261-2305-6.

- Rinehart, Robin (1 January 2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- Vedas (1 January 2003). The Vedas: With Illustrative Extracts. Book Tree. ISBN 978-1-58509-223-9.

Further reading[edit]

- L.A. Ravi Varma, "Rituals of worship", The Cultural Heritage of India, Vol. 4, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, Calcutta, 1956, pp. 445–463

- Jan Gonda, "The Indian mantra", Oriens, Vol. 16, (31 December 1963), pp. 244–297

- A.B. Keith, The Veda of the Black Yajus School entitled Taittiriya Sanhita, Harvard Oriental Series Vols 18-19, Harvard, 1914

- Gaurab Saha https://iskcondesiretree.com/profiles/blogs/gayatri-mantra-detailed-word-by-word-meaning