Bawa Muhaiyaddeen

Muhammad Raheem Bawa Muhaiyaddeen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | December 8, 1986 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Era | 20th century |

| Region | Sri Lanka, United States |

Muhammad Raheem Bawa Muhaiyaddeen (died December 8, 1986), also known as Bawa, was a Tamil-speaking teacher[1] and Sufi mystic from Sri Lanka who came to the United States in 1971,[2] established a following, and founded the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship in Philadelphia. He developed branches in the United States, Canada,[3] Australia and the UK — adding to existing groups in Jaffna and Colombo,[4] Sri Lanka. He is known for his teachings, discourses, songs, and artwork.

Bawa established vegetarianism as the norm for his followers[5] and meat products are not permitted at the legacy fellowship center or farm.[6]

Early life[edit]

Though little is known of his early personal life, Bawa Muhaiyaddeen's public career began in Sri Lanka in the early 1940s, when he emerged from the jungles of northern Sri Lanka. Bawa met pilgrims who were visiting shrines in the north, and gradually became more widely known. There were reports of dream or mystical meetings with Bawa that preceded physical contact.[4] According to an account from the 1940s, Bawa had spent time in 'Kataragama', a jungle shrine in the south of the island, and in 'Jailani', a cliff shrine dedicated to 'Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani of Baghdad, an association that links him to the Qadiri order of Sufism.[4] Many of his followers who lived around the northern town of Jaffna were Hindus and addressed him as swami or guru, where he was a medical and spiritual faith healer — and cured demonic possession.[4]

Subsequently, his followers formed an ashram in Jaffna, and a farm south of the city. After meeting business travelers from the south, he was invited to visit Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, at the time Ceylon. By 1967, the 'Serendib Sufi Study Circle' was formed by these Colombo predominantly Muslim students. Earlier in 1955, Bawa had set the foundations for a 'God's house' or mosque in the town of Mankumban, on the northern coast. This was the result of a "spiritual experience with Mary, Jesus' mother."[7] After two decades, the building was finished by students from the United States who were visiting the Jaffna ashram.[8] It officially opened and was dedicated in 1975.[9]

Bawa taught using stories and fables, reflecting the background of the student or listener and included Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim religious traditions; and welcomed persons from all traditions and backgrounds.[7]

Work in the United States[edit]

In 1971, Bawa was invited to come to the United States and subsequently moved to Philadelphia, [7] established a following, and formed the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship in 1973. The fellowship meeting house offered weekly public gatherings.[7]

As in Sri Lanka, Bawa developed a following among people of diverse religious, social and ethnic backgrounds, who came to Philadelphia to listen to him speak.[citation needed] In the United States, Canada and England, he was recognized by religious scholars, journalists, educators and leaders.[how?] The United Nations' Assistant Secretary General, Robert Muller, asked for Bawa's guidance on behalf of mankind during an interview in 1974.[10] During the Iranian hostage crisis of 1978–1980, he wrote letters to world leaders including Iran's Khomeini, Prime Minister Begin, President Sadat and President Carter to encourage a peaceful resolution to the conflict.[11][12] Time magazine, during the crisis in 1980, quoted Bawa as saying that when the Iranians understand the Koran "they will release the hostages immediately."[13] Interviews with Bawa appeared in Psychology Today,[14] the Harvard Divinity Bulletin,[15] and in The Philadelphia Inquirer[16] and the Pittsburgh Press. He continued teaching until his death on December 8, 1986.[citation needed]

Legacy[edit]

In May, 1984, the Mosque of Shaikh M. R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen was completed on the Philadelphia property of the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship, on Overbrook Avenue. Construction took 6 months and nearly all the work was done by the members of the fellowship under Bawa's direction.[17]

The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship Farm (100 acres (0.40 km2)) is in Chester County, Pennsylvania, south of Coatesville and prominently features Bawa's mausoleum, or mazar. Construction began shortly after his death and was completed in 1987. It is a destination for religious followers.[18]

Bawa created paintings and drawings symbolizing the relationship between man and God, describing his art work as "heart's work".[19] Two examples are reproduced in his book Wisdom of Man[20][21] and another is the front cover of the book Four Steps to Pure Iman.[22] In 1976, Bawa recorded and released an album of meditation, on Folkways Records entitled, Into the Secret of the Heart by Guru Bawa Muhaiyaddeen.[23]

In the United States, from 1971 to 1986, Bawa authored over twenty-five books,[24] created from over 10,000 hours of audio and video transcriptions of his discourses and songs. Some titles originated from Sri Lanka before his arrival in the U.S. and were transcribed later. The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship continues to study and disseminate this repository of his teachings. It has not appointed a new leader or Sheikh to replace his role as teacher and personal guide.[citation needed]

Vegetarianism[edit]

Bawa established vegetarianism as the norm for his followers as he believed the only compassionate choice is to eat without slaughter.[25] He stated that "we must be aware of everything we do. All young animals have love and compassion. And if we remember that every creation was young once, we will never kill another life. We will not harm or attack any living creature".[25] Bawa authored The Tasty Economical Cookbook, a two-volume vegetarian cookbook.[26]

Titles and honorifics[edit]

Bawa Muhaiyaddeen was referred to as Guru, Swami, Sheikh or 'His Holiness' depending on the background of the speaker or writer.[citation needed] He was also addressed as Bawangal by those Tamil speakers who were close to him and who wanted to use a respectful address.[citation needed] He often referred to himself as an 'ant man',[27] i.e., a very small life in God's creation. After his arrival in the United States, he was most often addressed as Guru Bawa or simply Bawa, and he established the fellowship. By 1976, he felt that the title 'guru' had been abused by others who were not true teachers and dropped the title Guru, with the organization becoming the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship.[28]

By 2007, an honorific, Qutb, was used by his students in the publications of his talks.[29] Qutb means pole or axis, and signifies a spiritual center.[30] The name Muhaiyaddeen means 'the giver of life to true belief' and has been associated with previous Qutbs.

Quotes[edit]

- "The prayers you perform, the duties you do, the charity and love you give is equal to just one drop. But if you use that one drop, continue to do your duty, and keep digging within, then the spring of God's grace and His qualities will flow in abundance."[31]

- "People with wisdom know that it is important to correct their own mistakes, while people without wisdom find it necessary to point out the mistakes of others. People with strong faith know that it is important to clear their own hearts, while those with unsteady faith seek to find fault in the hearts and prayers of others. This becomes a habit in their lives. But those who pray to God with faith, determination, and certitude know that the most important thing in life is to surrender their hearts to God."[32]

- "The things that change are not our real life. Within us there is another body, another beauty. It belongs to that ray of light which never changes. We must discover how to mingle with it and become one with that unchanging thing. We must realize and understand this treasure of truth. That is why we have come to the world."[33]

- "My love you, my children. Very few people will accept the medicine of wisdom. The mind refuses wisdom. But if you do agree to accept it, you will receive the grace, and when you receive that grace, you will have good qualities. When you acquire good qualities, you will know true love, and when you accept love, you will see the light. When you accept the light, you will see the resplendence, and when you accept that resplendence, the wealth of the three worlds will be complete within you. With this completeness, you will receive the kingdom of God, and you will know your Father. When you see your Father, all your connections to karma, hunger, disease, old age will leave you."[34]

- My grandchildren, this is the way things really are. We must do everything with love in our hearts. God belongs to everyone. He has given a commonwealth to all His creations, and we must not take it for ourselves. We must not take more than our share. Our hearts must melt with love, we must share everything with others, and we must give lovingly to make others peaceful. Then we will win our true beauty and the liberation of our soul. Please think about this. Prayer, the qualities of God, the actions of God, faith in God, and worship of God are your grace. If you have these, God will be yours and the wealth of the world to come will be yours. My grandchildren, realize this in your lifetime. Consider your life, search for wisdom, search for knowledge, and search for that love of God which is divine knowledge, and search for His qualities, His love, and His actions. That will be good. Amin. Ya Rabbal-'alamin. So be it. O Ruler of the universes. May God grant you this."[35]

- "God has a home inside of our heart. We must find a home inside of God's home inside of our heart" - Shared by Bawa Mahaiyaddeen in conversation with advocate for the homeless at the Muhaiyaddeen community in Philadelphia - 1986.

Writings by students and others[edit]

Books by his followers and others about M.R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen include:

- Owner's Manual for the Human Being by Mitch Gilbert, One Light Press publisher, 2005, ISBN 0-9771267-0-6

- The Illuminated Prayer: The Five-Times Prayer of the Sufis by Coleman Barks and Michael Green, Ballantine Wellspring publisher, 2000, ISBN 0-345-43545-1. According to the publisher, the book "offers a compelling introduction to the wisdom and teachings of the beloved contemporary Sufi master Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, who brought new life to this mystical tradition by opening a passage to its deepest, universal realities. It is the loving handiwork of two of Bawa's best-known students, Coleman Barks and Michael Green, who also created The Illuminated Rumi."

- One Song: A New Illuminated Rumi by Michael Green, Running Press publisher, 2005, ISBN 0-7624-2087-1

- My Years with the Qutb: A Walk in Paradise by Professor Sharon Marcus, Sufi Press publisher, 2007, ISBN 0-9737534-0-4

- THE MIRROR Photographs and Reflections on Life with M.R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen (Ral.) by Chloë Le Pichon and Dwaraka Ganesan and Saburah Posner and Sulaiha Schwartz, published privately by Chloë Le Pichon, 2010, ISBN 0-615-33211-0. A 237-page large-format photographic compilation with commentary by 78 contributors.

- Life with the Guru by Dr. Art Hochberg, Kalima publisher, 2014, ISBN 0988807556

- The Elixir of Truth: Journey on the Sufi Path, Volume One by Musa Muhaiyaddeen, Witness Within publisher, 2013, ISBN 0989018504

- Finding the Way Home by Dr. Lockwood Rush, Ilm House publisher, 2007, ISBN 0972660712

- GPS for the Soul: Wisdom of the Master by Dana Hayne, BalboaPress publisher, 2017, ISBN 1504384040

Coleman Barks, a poet and translator into English of the works of the 13th-century Sunni Muslim poet Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī, described meeting Bawa Muhaiyaddeen in a dream in 1977.[36] After that experience he began to translate the poems of Rumi. Coleman finally met Bawa Muhaiyaddeen in September, 1978 and continued to have dreams where he would receive teachings.[36] Coleman's likens Bawa Muhaiyaddeen to Rumi and Shams Tabrizi, the companion of Rumi.[37] Artist Michael Green worked with Coleman Barks to produce illustrated version of Rumi's works.[38][39]

In "Blue-Eyed Devil", Michael Muhammad Knight attempts to receive a message from Bawa in a dream, in a Sufi practice called istikhara. He travels to the mazar and unsuccessfully tries to fall asleep on the cushions, but is awakened by the groundskeeper.[40]

The band mewithoutYou explored Bawa's teachings throughout their discography, most notably in their fourth album, It's All Crazy! It's All False! It's All a Dream! It's Alright. The teacher's story of "The Fox, the Crow, and the Cookie" from My Love You My Children: 101 Stories for Children is told as well as his story about the "King Beetle" from The Divine Luminous Wisdom that Dispels Darkness.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Malik and Hinnells, p. 90.

- ^ Divine Luminous Wisdom, p. 254.

- ^ Malik and Hinnells, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d Malik and Hinnells, p. 91.

- ^ God, His Prophets and His Children, pgs. 150–157

- ^ Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship web-site Farm page

- ^ a b c d Malik and Hinnells, p. 92.

- ^ Malik and Hinnells, p 92.

- ^ The Tree That Fell to the West, p. 171.

- ^ To Die Before Death, p. xix.

- ^ Haddad and Smith, p 103.

- ^ The Truth and Unity of Man: Letters in Response to a Crisis

- ^ "Is the Ayatullah a Heretic?" Time. April 28, 1980.

- ^ Keen, Sam (April 1976). "The Mind is in the Heart". Psychology Today.

- ^ Harvard Divinity Bulletin. Harvard University Divinity School. December 1982 – January 1983, Volume XIII, Number 2

- ^ Haddad and Smith, p 104.

- ^ Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship web-site.

- ^ Xavier, M. Shobhana. "An American Sufi Shrine, Bawa's Mazar in Coatesville, Pennsylvania." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2016.5 http://mavcor.yale.edu/conversations/object-narratives/american-sufi-shrine-bawa-s-mazar-coatesville-pennsylvania

- ^ Acknowledgments page, Wisdom of Man

- ^ Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. Bawa (June 7, 1994). The Wisdom of Man: Selected Discourses. Fellowship Press. ISBN 9780914390459 – via Google Books.

- ^ Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. Bawa (June 7, 1994). The Wisdom of Man: Selected Discourses. Fellowship Press. ISBN 9780914390459 – via Google Books.

- ^ Four Steps to Pure Iman, front cover.

- ^ "Smithsonian Folkways recording FW08905".

- ^ Islam and World Peace, pg.173.

- ^ a b Kemmerer, Lisa. (2012). Animals and World Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0199790678

- ^ "Tasty, Economical Cookbook: Vegetarian Recipes by M. R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen". rumisgarden.co.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ The Tree That Fell to the West, p. 165.

- ^ Truth and Light, p. 10.

- ^ The Point Where God and Man Meet, p. xi.

- ^ Resonance of Allah, p. 716.

- ^ Sheikh and Disciple, p. 63.

- ^ Islam and World Peace, p. 3.

- ^ Questions of Life Answers of Wisdom, Vol.1, p. 220.

- ^ Come to the Secret Garden, p. 188.

- ^ My Love you My Children; p. 466.

- ^ a b Rumi: the Book of Love, p. 140.

- ^ Nov. 12, 2007 interview by Chitra Kalyani, IslamOnline.Net article Archived January 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Xavier, M. Shobhana. "From Illuminated Rumi to the Green Barn: The Art of Sufism in America." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2016.4 http://mavcor.yale.edu/conversations/object-narratives/illuminated-rumi-green-barn-art-sufism-america

- ^ Xavier, M. Shobhana. "Interview with American Sufi Artist Michael Green." Interview. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016). doi:10.22332/con.int.2016.1 http://mavcor.yale.edu/conversations/interviews/interview-american-sufi-artist-michael-green

- ^ "Blue-Eyed Devil", pg. 86-88.

References[edit]

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1972). The Divine Luminous Wisdom That Dispels the Darkness. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-11-2.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1974). Truth and Light: Brief Explanations. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-04-X. Radio Interviews by Lex Hixon – WBAI, New York, and Will Noffke – KQED, San Francisco

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1976). God, His Prophets and His Children. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-09-0.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1976). My Love You, My Children: Stories for Children of All Ages. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-20-1.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1980). The Truth and Unity of Man: Letters in Response to a Crisis. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-15-5.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1980). The Wisdom of Man: Selected Discourses. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-45-7.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1983). Sheikh and Disciple. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-26-0.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1985). Come to the Secret Garden. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-46-5.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (1997). To Die Before Death: The Sufi Way of Life. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-39-2.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (2001). Questions of Life, Answers of Wisdom, Vol. 1. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-32-5.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (2001). The Resonance of Allah: Resplendent Explanations Arising from the Nur, Allah's Wisdom of Grace. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-61-9.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (2003). The Tree that Fell to the West: Autobiography of a Sufi. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-67-8.

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (2004). Islam and World Peace: Explanations of a Sufi. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-65-1.*Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. (2006). The Point Where God and Man Meet. Philadelphia: The Fellowship Press. ISBN 0-914390-79-1.

- Y. Y. Haddad and J. I. Smith, editors (1994). Muslim Communities in North America. Albany: SUNY. ISBN 0-7914-2019-1.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) Chapter 4: Tradition and Innovation in Contemporary American Islamic Spirituality: The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship by Dr. Gisela Webb, Professor of Religious Studies at Seton Hall University - J. Malik and J. Hinnells, editors (2003). Sufism in the West. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-27407-9.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) Chapter 4: Third Wave Sufism in America and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship by Dr. Gisela Webb, Professor of Religious Studies at Seton Hall University - Xavier, M. Shobhana (2015). Masjids, Ashrams and Mazars: Transnational Sufism and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University dissertation.

- Xavier, M. Shobhana. "Interview with American Sufi Artist Michael Green." Interview. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016). doi:10.22332/con.int.2016.1 Interview with American Sufi Artist Michael Green

- Xavier, M. Shobhana. "An American Sufi Shrine, Bawa's Mazar in Coatesville, Pennsylvania." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2016.5 An American Sufi Shrine, Bawa’s Mazar in Coatesville, Pennsylvania

- Xavier, M. Shobhana. "From Illuminated Rumi to the Green Barn: The Art of Sufism in America." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2016.4 From Illuminated Rumi to the Green Barn: The Art of Sufism in America

- Snyder, Benjamin H. (2003). HEARTSPACE: The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship and the Culture of Unity. Philadelphia: Haverford College thesis.

- Barks, Coleman (2005). Rumi: The Book of Love: Poems of Ecstasy and Longing. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-075050-2.

External links[edit]

Websites

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Wikiquote page

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship Web Site

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship Farm Web Site

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Serendib Sufi Study Circle Web Site

Scholarly articles and dissertations

- Tradition and Innovation in Contemporary American Islamic Spirituality: The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship – Chapter 4 of Muslim Communities in North America by Gisela Webb, Professor of Religious Studies at Seton Hall University

- Third Wave Sufism in America and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship – Chapter 4 of Sufism in the West by Gisela Webb, Professor of Religious Studies at Seton Hall University

- Speaking with Sufis - Chapter 11 of Interreligious Dialogue and Cultural Change by Frank J. Korom, Professor of Religion and Anthropology at Boston University

- Longing and belonging at a Sufi saint shrine abroad - Chapter 4 of Islam, Sufism and Everyday Politics of Belonging in South Asia by Frank J. Korom, Professor of Religion and Anthropology at Boston University

- Masjids, Ashrams and Mazars: Transnational Sufism and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship Wilfrid Laurier University Ph.D. dissertation by M. Shobhana Xavier

- Bawa Muhaiyaddeen: A Study Of Mystical Interreligiosity Temple University Ph.D. dissertation by Saiyida Zakiya Hasna Islam, August 2017

- Do Sufis Dream of Electronic Sheikhs? The Role of Technology Within American Religious Communities University of Florida M.A. thesis by Jason Ladon Keel

- HEARTSPACE: The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship and the Culture of Unity Haverford College Thesis by Benjamin Snyder

Online books and videos

- M. R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Books Online at Books.Google.Com

- "The Pearl of Wisdom (Guru Mani)", Serendib Sufi Study Circle book of discourses from the 1940s translated into English and published January, 2000.

- "Wisdom of the Divine Part 5", Serendib Sufi Study Circle publication.

- Video discourse "True Love", February 9, 1980, Philadelphia, 55 min.

- Video discourse "The True Dimensions of the Dhikr", (practicing the constant remembrance of God), Lex Hixon Interview, May 18, 1975, WBAI Radio studio, New York City, 60 min.

- Compendium of discourses and readings "Love All Lives as Your Own", discourses recorded November 9,1980 and September 30,1983, 28 min.

- Video Discourse "The Learning of an Ant Man" May 18, 1975, St. Peter's Church, New York City, 83 min.

- Interview with Bawa Muhaiyaddeen in Philadelphia on Kindred Spirits public radio show by David Freudberg

Other external links

- Coleman Bark's dream of Bawa Muhaiyaddeen

- Into the Secret of the Heart by Guru Bawa Muhaiyaddeen record details at Smithsonian Folkways

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

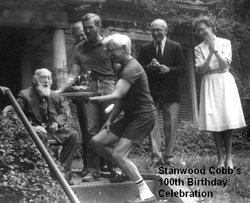

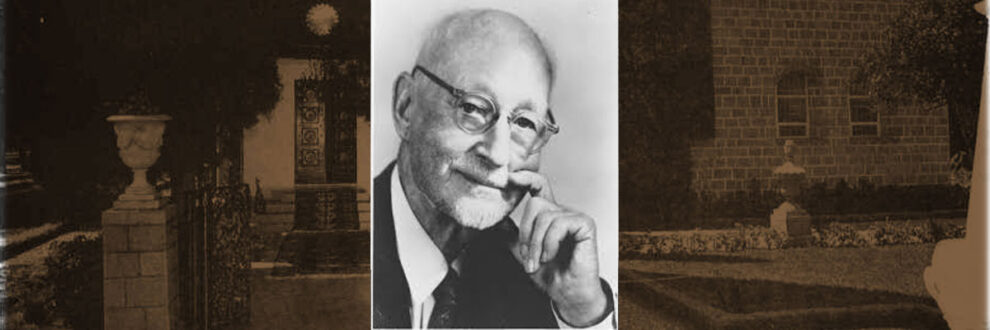

Stanwood Cobb

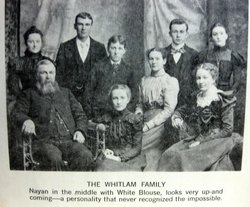

Stanwood Cobb On September 19, 1919 he married Ida Nayan Whitlam who was a member of several literary associationswho later died in 1967. They had no children.

On September 19, 1919 he married Ida Nayan Whitlam who was a member of several literary associationswho later died in 1967. They had no children.