This annotated bibliography is composed of both seminal and recent works on Christianity in early modern and modern Japan. As reflected in the selections here, the vast majority of scholarship on this topic is focused on two historical moments—the “Christian Century” of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and Protestant Christianity in the Meiji Period. This annotated bibliography is a first attempt to review a few frequently-cited works as well as more recent scholarship, and is by no means comprehensive. Given my own orientation as a student of history, I have also restricted this list primarily to works arising out of that discipline.*

Anderson, Emily. “Tamura Naoomi’s ‘The Japanese Bride’: Christianity, Nationalism, and Family in Meiji Japan.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 34, no. 1 (2007): 203-228.

Historian Emily Anderson examines the strongly condemning responses to the publication of Christian minister Tamura Naoomi’s English-language book, The Japanese Bride in 1893, bringing to light the intersections of nationalism, religion, and family in modern Japan. In his controversial English-language publication, Tamura described Japanese marriage and familial customs and compared them to American ones observed in his travels, a comparison perceived as an attack on the Japanese family and a betrayal of Japanese Christianity and the nation at large. Nationalists and Japanese Christians, as Anderson argues, saw the work as jeopardizing Japanese Christians’ authority over a foundational aspect of Japanese society (the family) and undermining the parity that Japanese sought with Western nations, which it needed for its imperialist enterprise. As she writes, “By characterizing Japanese families—the very core of the nation—as shameful, backwards, and unhappy, Tamura was in fact defying the central argument of Japanese claims to modern legitimacy” (225). His publication thus revealed the anxieties of the Japanese nation about its position not only in East Asia, but vis-à-vis the West.

Anderson contextualizes Tamura’s publication within a larger collection of his writings as well as a host of other Japanese-language archival materials. Like Notto Thelle’s study on the Buddhist-Christian relationship, Anderson’s study interrogates the relationship between nationalism, Christianity, and anti-Westernism in Meiji Japan.

Breen, John and Mark Williams, eds. Japan and Christianity: Impacts and Responses. London: Macmillan, 1996.

Japan historian John Breen and literature scholar Mark Williams aim in this compilation, the product of a 1991 conference on Christianity in Japan, to complicate the “Western ‘impact’ and an “Eastern” ‘response’” structure used in understanding Christianity in Japan (1). They frame their study by setting in conversation two scholars—Ebisawa Arimichi, who has argued that Christianity laid a crucial foundation for Tokugawa thought, and George Elison, who declared less positively that in the Japanese context Christianity’s “cultural contribution was nil’ (Elison, qtd. in Breen and Williams, 2).

The collection covers a broad scope of topics and periods, from Christianity from the Tokugawa period to the twentieth century by Mark Mullins, Notto Thelle, Helen Ballhatchet, John Breen, Michael Cooper, Stefan Kaiser, Ohashi Yukihiro (the only Japanese scholar included), Stephen Turnbull, Christal Whelan, and Mark Williams. Collectively, they aim to show the slow but myriad processes by which Japanese interacted with Christian and Western ideas and institutions, and, importantly, the ways in which Japan contributed back to Western Christianity. Topics range from Western-style painting in Japan to the tensions between evolutionary theory and Christian theology to Japanese literary works on Christianity.

Elison, George. Deus Destroyed: The Image of Christianity in Early Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973.

In this seminal work, George Elison challenges narratives of Catholicism in Tokugawa Japan—the “Christian Century”—by eschewing the “Western” point of view adopted by scholars in favor of one that approaches the topic from the “inside,” made possible by his translation of Japanese-language anti-Christian texts. (The title of his book is from an anti-Christian tract written by Japanese Jesuit convert later turned skeptic, Fabian Fucan.) The book is composed of two main sections: the first, an analysis of Christianity in Japan from entry in 1549 to its rejection by the state; the second, translations of four anti-Christian works by Japanese Buddhists, Confucians, and apostate Jesuits. Though acknowledging the complexity of the history of Christianity in Japan, Elison is quite clear in his position that Christianity failed to make any lasting positive contributions to Japan, instead reifying the state’s control over society and religion and contributing to its continued isolation. Elison’s challenge to the legacies of Christianity as well as his contribution of translated texts make this a key work in assessing Christianity both in the Tokugawa period and its continued influence in Japan today.

Hardacre, Helen. Shinto and the State, 1868-1988. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Historian Helen Hardacre aims to change the “faceless quality of research on State Shinto” by examining peripheral voices, particularly those of the priesthood, to understand interactions between the state and Shinto between 1868 and 1945. Hardacre argues that Shinto as a religion of Japan was invented after the Meiji Restoration—the word itself is “purely a modern, post-Meiji invention”—and that this invented tradition has been enlisted in the service of the creation of the modern nation (19, 4). Nevertheless, her decision to omit the 1930-1945 period from her analysis does seem to be a critical missed opportunity to bolster her argument about Shinto’s cooptation as a handmaiden of the state.

Hardacre’s work on religion draws attention to another aspect of the state-invented tennosei system on which scholars such as Carol Gluck (Japan’s Modern Myths, 1985) and Takashi Fujitani (Splendid Monarchy, 1996) have also focused. Her argument that postwar Shinto faces serious challenges because of its loss of hegemony over national symbols and because of the rise of religious pluralism also contrasts with Daniel Holtom’s more optimistic conclusion (Modern Japan and Shinto Nationalism, 1943).

—. Religion and Society in Nineteenth-Century Japan: A Study of the Southern Kanto Region, Using Late Edo and Early Meiji Gazetteers. Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 2002.

In this more recent publication, Helen Hardacre presents a detailed study of Buddhist and Shinto institutions from the 1830s to the early Meiji period. Rather than simply tracing the historical development of a single religion, she adopts the method of examining institutions (temples and shrines) within a given geographic area. A secondary aim is to examine the impact of the transition between the Tokugawa and Meiji periods on religious institutions and popular religious life. Hardacre argues provocatively that the Meiji state’s adoption of Shinto did not necessarily guarantee the dwindling of Buddhism in Japan; it was instead local factors that were most influential in the decline of Buddhist shrines. Hardacre’s point thus runs counter to that of Shigeyoshi Murakami and Thelle, who take a state-centric approach to religion in Japan.

Also in contrast to broader works like Murakami’s, Hardacre’s work maintains a sharp focus on a specific region. In the process of focusing on the local, however, Hardacre does not connect her findings to larger trends in Japanese religion; further historical and historiographical context would be beneficial to evaluating her desired contribution. It may be fruitful to compare her work with Mary Elizabeth Berry’s Japan in Print (2007), which also uses gazetteers.

Higashibaba, Ikuo. Christianity in Early Modern Japan: Kirishitan Belief and Practice. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2001.

Comparative religions scholar Ikuo Higashibaba is interested in this monograph on popular forms of religion and “culture of ordinary Japanese followers,” whom he terms the “laity,” within the Kirishitan community in early modern Japan (xiv, xvi). He argues that these commoners practiced a form of religious syncretism that is often omitted from existent narratives of Christianity in Tokugawa Japan, which have focused on orthodox Catholic belief, and that the earlier acceptance and syncretization of Buddhism set the precedent for acceptance of foreign religions. Like Kitagawa, Higashibaba adopts a “history of religions” approach in which he places Kirishitan beliefs, practices, and symbols within their historical and cultural contexts, drawing particularly on Jonathan Z. Smith’s theoretical work (1987).

Higashibaba’s work is the most recent in a line of works on the Kirishitan community in Tokugawa Japan. His attempt to shift the focus of discussion from intellectual or theological discussions of Catholicism to popular religions provides a counterpoint to works like Elison’s. Nevertheless, it is unclear how exactly he measures the fidelity of the believers—were they really Kirishitans?—whom he makes the focus of his study. Moreover, his thesis that Catholicism became a Japanese religion is neither unique nor a significant intervention in the historiography—this work should be valued for its topical focus rather than actual argument.

Howe, John F. “Japanese Christians and American Missionaries.” In Changing Japanese Attitudes Toward Modernization, edited by Marius B. Jansen, 337-366. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965.

John F. Howe’s contribution to a 1965 collection edited by the late Marius Jansen focuses on Japanese Christians’ experience of psychological “self-abasement” resulting from the belief that Meiji Japan was lagging behind in modernization compared to the West. Through an examination of Japanese Christian and Western missionary, Howe highlights the similarities between ten influential figures—five Americans and five Japanese—and their cooperative religious efforts, which became to be increasingly challenged by growing anti-Western and nationalist sentiment in the 1880s. Howe identifies this at the point that Japanese Christian leaders, with the exception of Uchimura Kanzo, decided to break from their Western brethren to fashion their own version of Christianity, which helped them overcome their own self-abasement.

As in his 2005 book, Howe takes a psychohistorical approach in this work. While he makes a notable attempt at showing the very personal impact of modernization and Christianity in Japan, his reasons for the selection of the main figures in his book are not clear and his narrative of overcoming “self-abasement” strikes one as a bit simplistic.

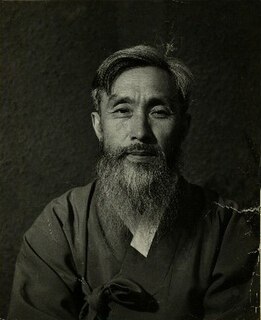

—. Japan’s Modern Prophet: Uchimura Kanzo, 1861-1930. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2005.

In a book that has generated much discussion, given the apparently vast amount of scholarship on Uchimura Kanzo (1861-1930) and the author’s provocative perspective, John Howe presents a nearly hagiographic account of Uchimura’s life as a leading Japanese Christian intellectual.[1] Lauding a native convert’s deep engagement with and mastery of a foreign religion, Howe places Uchimura alongside “the Old Testament prophets, Dante, Luther, Kierkegaard, Carlyle, and Gandhi” (11). According to Howe, the author and theologian bridged East and West by developing a distinct “Japanese Christianity” in which he fused Japanese sociocultural values with those of Christianity, and rejected foreign missionaries in favor of his non-church movement (mukyokai). Drawing on Uchimura’s publications and correspondences, Howes attempts to intervene in the rather large historiography on Uchimura by highlighting his eschatological beliefs and emphasis on “individual faith and morality,” rather than his well-known opposition to war and founding of mukyokai (388). Unfortunately, any real critical examination if missing from this book; Howe neglects to show why people disliked Uchimura as well as incorporate what might have been useful theoretical perspectives on religion and nationalism into his work.

Ion, Hamish. American Missionaries, Christian Oyatoi, and Japan, 1859-1873. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2009.

In this monograph on Christian oyatai (foreign employees) and Episcopalian, Congregational, Presbyterian, and Dutch Reformed missionaries, historian Hamish Ion seeks to challenge the existent narrative of Christianity in late Tokugawa and early Meiji Japan—pointing out Howe’s 1965 essay in particular—which he articulates as a binary of “acceptance or rejection” (285). His thesis is that despite the missionaries’ commendable optimism and vigor, the period from 1859 to 1873 already foretold the demise of the effort to Christianize Japan, not due to any failure of the missionaries and oyatoi, but Tokugawa and Meiji state policies regarding religion and the relative lack of support from American diplomats. Like Anderson and Thelle, he thus contextualizes Christianity in Japan within the global politics and cultural exchanges of the era. Ion draws from a broad array of primary documents by the American Church mission, individual missionaries, and diplomatic materials. He also engages heavily with the secondary literature, rejecting the applicability of Said’s orientalism to oyatoi, since recording the experiences of the “other” was not a focus of missionary records.

Kitagawa, Joseph Mitsuo. Religion in Japanese History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1966, repr. 1990.

This work is a compilation of six lectures given by historian of religion Joseph Kitagawa on religion in Japan from the Heian period to the postwar period, an endeavor he calls “autobiographical” given his own background. Despite the broad scope of these lectures in both time and topics covered, Kitagawa announces that he is attempting to apply a Religionswissenschaft (science/history of religion) approach, eschewing the “peculiar Western convention to divide human experience into such semi-autonomous categories as religion, philosophy, ethics, aesthetics, culture, society, etc.” in favor of continuing the spirit of Ritsuryo, Tokugawa, and Meiji syntheses of these categorizations (xiii). It is difficult to understand exactly what Kitagawa means by a Religionswissenschaft approach, though it appears to be in the vein of Max Muller’s rejection of classifications. Rather than examine religions individually, Kitagawa attempts to understand the “universal phenomenon called ‘religion’” within the Japanese historical context (3). Of particular interest to the scholar of Christianity in Japan are Kitagawa’s fourth and fifth lectures. In the fourth, he examines the relationship between Christianity and neo-Confucianism respectively to the Tokugawa regime; in the fifth, he briefly touches on the impact of Christianity on Japanese modernization, in which Japan preserved the age-old principle of “immanental theocracy” through state Shinto.

Mullins, Mark. Christianity Made in Japan: A Study of Indigenous Movements. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1998.

Sociologist Mark Mullins asks in this volume how a religion comes to be indigenized, focusing appropriately on the “indigenous and independent expressions of Christianity” in Japan. He argues for a shift in understanding Christianity as a “Western” to viewing it as a “world” religion, much like Buddhism and Islam, which adapts to a given context. There is, therefore, no pure Christianity but rather localized forms. Like Higashibaba, he is interested less in the mainstream versions of Christianity, instead focusing his study on thirteen indigenous groups from the Meiji Period and onward that developed apart from the influence of missionaries and churches. The book includes discussions of Uchimura Kanzo’s mukyokaimovement, among other subgroups, the confluence of Christianity and concerns for ancestors, and a fascinating comparison of Christianity in Korea and transplanted Korean Christianity in Japan.

This book is based on fieldwork that the author conducted primarily in the Kanto and Kansai regions. Perhaps most provocative in this work is the author’s validation of syncretistic, indigenous Christian groups as critical, defining incarnations of Christianity, rather than heterodox deviations from the theological standard, by placing them at the center of his argument on the nature of universal religions. Mullin’s science of religion approach stands in stark comparison to studies oriented to theological belief.

Nirei, Yosuke. “Globalism and Liberal Expansionism in Meiji Protestant Discourse.” Social Science Japan Journal15, no. 1 (2012): 75-92.

Historian Yosuke Nirei charts the liberal Christian arguments of Uchimura Kanzo (1861-1930) and his Protestant colleagues in this recent article. He argues that Uchimura adopted the ideology of liberal expansionism, defined as espousing “Japan’s expansion through peaceful and economic means in tandem with British and American imperialism and emigration overseas,” to justify the Sino-Japanese War and Japan’s advance in Asia (75). Rather than citing political or economic justifications alone for expansionism, Uchimura developed a brand of expansionism ideologically driven by the ideals of freedom and rhetoric of civilization. (Later, he would advocate complete pacifism as his theology became more conservative, but Nirei’s focus is on his earlier, liberal convictions.) The large part of this article is composed of comparisons that Nirei draws between Uchimura and his contemporaries Takekoshi Yosaburo, Tokutomi Soho, and Yamaji Aizan, as well as Leo Tolstoy, which makes for rather dense reading.

The extent of Uchimura’s massaging of Protestant theology to fit the Japanese political and cultural contexts, as Nirei shows, accords with many other studies included in this bibliography on the “indigenization” of Christianity. Here, Nirei shows that indigenization did not simply occur at the level of popular, “common” practices, but at an intellectual, discursive level as well. Greater contextualization with the Japanese religious milieu at the end of the twentieth century, as well comparisons with Western liberal theology, are also opportunities for expansion.

Oshiro, George M. “Nitobe Inazō and the Sapporo Band: Reflections on the Dawn of Protestant Christianity in Early Meiji Japan.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 34 (2007): 99-126.

The title of historian George Oshiro’s article is misleading, because it supposes a much broader scope than the author actually takes. Oshiro presents a short biographical sketch of Nitobe Inazo (1862-1933), best known for his 1990 publication of Bushido but also a Protestant Christian internationalist who grappled with “attain[ing] a genuine Christian faith free from the taint of foreign culture” (99). Oshiro narrates Nitobe’s childhood interest in and openness to Christianity, followed by his time at Sapporo Agricultural College (SAC) during which time he made friends with Miyabe Kingo, Uchimura Kanzo, and others of the “Sapporo Band.” Oshiro draws attention to Nitobe’s doubts about Christianity, especially its soteriological aspects, and argues that it was only in meeting the Quakers while studying at Johns Hopkins a few years later that he found real, satisfying answers to his spiritual questions.

Where Oshiro comes far short is in providing his promised “reflections” on Protestant Christianity at large in early Meiji Japan. Oshiro’s sketch of Inazo also lacks a serious engagement with the question of how Quakerism quelled—theological, or otherwise—Nitobe’s worries that “he could not, to be intellectually honest, believe in the grace of an all-loving Savior,” as well as how to set Nitobe’s evolving religious views in the broader religious and intellectual context of Meiji Japan (111).

Paramore, Kiri. Ideology and Christianity in Japan. 1st ed. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2010.

Drawing on a rich array of Japanese anti-Christian texts from 1600 to 1900, intellectual historian Kiri Paramore seeks to challenge existent conceptions of anti-Christian discourse in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (the “Christian Century”) and in the nineteenth century as disparate, stressing instead the discursive continuities between the two periods. He thus discards the couching of anti-Christian discourse in the Tokugawa period in a “religious paradigm” versus the placement of Meiji Christian discourse in a the political context. Paramore instead argues that anti-Christian discourse was less about Christianity itself and more about power and conflicts in domestic politics in both the Tokugawa and Meiji periods. Secondarily, he also seeks to dispel the common “Western vs. Eastern” trope that has characterized the reception of Christianity in the Tokugawa period.

In Paramore’s narrative, religion is co-opted by politics; one may therefore draw parallels between Paramore’s work and those on state Shinto, as well as Perelman’s dissertation on the political motives of missionaries.

Perelman, Elisheva Avital. “The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century.” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2011.

In this recently submitted dissertation, historian Elisheva Perelman brings under critical examination the work of foreign Christian evangelical missionaries in the Meiji and Taisho periods during both a time of modernization and the unattended spread of disease—specifically, tuberculosis—in Japan. Though Japan saw the rise of science research and modern medicine under the Meiji and Taisho states, tuberculosis also spread unchecked at a rapid pace amongst the urban population and received little governmental attention. Perelman argues that the foreign missionaries who did attend to Japanese tubercular were ruled by political interests. Missionaries focused their attentions on evangelism to the nation’s elite so as to gain financial support as well as the marginalized sick so as to ingratiate themselves to the government by filling a public health need; her answer to the quintessential question of whether missionaries are truly selfless is rather damning. Furthermore, the political motives that laced their medical work “made individuals with a disease into a collective, and, in doing so, removed their agency, essentially creating pawns for the constantly evolving chess games between the organizations and the government” (4).

This work creatively draws together themes of disease, evangelization, gender, and modernization, drawing on an array of missionary archives, hospital records, and Japanese-language sources. Perelman also importantly raises the methodological question of discerning intent and motive, particularly relevant in studying foreign missionaries, to which she provides one response.

Thelle, Notto R. Buddhism and Christianity in Japan: From Conflict to Dialogue, 1854-1899. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1987.

Missiologist Notto Thelle examines the Christian-Buddhist relationship between 1854 and 1899 by placing it in a larger political and social context. Before 1890, Buddhists saw the newly imported Western Christianity as a threat to their power and social order, whereas Christians dismissed Buddhists as innocuous and irrelevant due to corruption and lack of “spiritual vigor” within its ranks (249). With the passage of the Meiji Constitution in 1889, Thelle argues, the tables were turned and Christianity was placed on the defensive. Nevertheless, in this period debates over nationalism that had driven the two religions apart also worked to bring them into friendlier dialogue. He seems to have identified one critical period in which Christianity became part of Japan’s syncretistic religious fabric (a characterization found also in Hardacre and Byron Earhart’s works).

Thelle draws on a rich variety of primary sources by various Japanese leaders and Buddhist and Christian publications. The work is, however, not without faults: Thelle’s use of the terms “Buddhist nationalism” or “Christian nationalism” are not accompanied by clear definitions. More importantly, the author ignores the impact of State Shinto and the 1873 repeal of the ban on Christianity, significant points in Japanese religious history.

*In compiling this bibliography, I am building on work completed for HISTORY 396D: Modern Japan in Fall Quarter 2012 at Stanford University, which focused more broadly on religion in Japan.

[1] James L. Huffman, review of Japan’s Modern Prophet, by John F. Howes, Monumenta Nipponica 62, no. 3 (Autumn 2007): 366-369; Shibuya Hiroshi, review of Japan’s Modern Prophet, by John F. Howes, Church History 78, no. 1 (March 2009): 147-151; John F. Howes, “Responses to comments on Japan’s Modern Prophet,” Church History 78, no. 1 (March 2009): 151-158.

1

1 Related Identities

Related Identities