7 The Greening of Buddhism Stephanie Kaza

The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology

AS A MAJOR WORLD RELIGION, BUDDHISM HAS A LONG and rich history of responding to human needs. From the moist tropical lowlands of Sri Lanka to the towering mountains of Tibet, Buddhist teachings have been transmitted through diverse terrain to many different cultures. Across this history, Buddhist understanding about nature and human-nature relations has been based on a wide range of teachings, texts, and social views. The last half century, as Buddhism has taken root in the West, has been a time of great environmental concern. Global warming, habitat loss, and resource extraction have all taken a significant toll as human populations multiply beyond precedent.

With the rise of the religion and ecology movement, Buddhist scholars, teachers, and practitioners have investigated the various traditions to see what teachings are relevant and helpful for cultivating environmental awareness. The development of green Buddhism is a relatively new phenomenon, reflecting the scale of the environmental crisis around the world. Thus far the gleanings have followed the lead of specific writers and teachers opening up new interpretations of Buddhist teachings.

This essay was originally prepared for The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology, edited by Roger Gottlieb, published by Oxford University Press in 2006. Since that time there have been further developments in Buddhist eco-activism and Buddhism and Ecology scholarship, with emphasis on climate change, animal protection, and social justice. Buddhist writers, teachers, and activists continue to draw on the central philosophical and religious themes from the major Buddhist traditions highlighted here.

Western Buddhists, still new to the philosophies and practices of the East, have often sparked the conversations, seeking ways to complement secular approaches to environmental thought.

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF GREEN BUDDHISM

One of the earliest voices for Buddhist environmentalism in North America was Zen student and poet Gary Snyder, who illuminated the connections between Buddhist practice and ecological thinking.' Snyder studied Zen in Japan and cultivated an "in the moment" haiku-like form in his poetry; much of which was set in the mountains of the western United States. One of his more lighthearted pieces, "Smokey the Bear Sutra," was handed out by activists urging better protection for US forests. Snyder was associated with the early Beat generation of the 1950s and 1960s, which had a strong influence on the 1960s counterculture. Hippies, communards, and back-to-the-landers took up Snyder's approach, made popular in Jack Kerouac's travelogue Dharma Bums. Many early Buddhist students felt that spiritual leadership was crucial in the race toward planetary ecological destruction.

In the 1970s the environmental movement swelled, and Buddhist centers became well established in the West. While Congress passed such landmark legislation as the Clean Water Act, some of the new retreat centers confronted ecological issues head on. Zen Mountain Monastery in New York challenged the Department of Environmental Conservation over a beaver dam and forest protection. Green Gulch Zen Center in Northern California worked out water-use agreements with the neighboring farmers and national park. Some Buddhist centers opted for vegetarian fare at a time when vegetarianism was not that well known. For a few, this reflected an awareness of the environmental problems associated with raising meat. A number of Buddhist centers made some effort to grow their own organic food.

By the 1980s Buddhist leaders were explicitly addressing the eco-crisis and incorporating ecological awareness in their teaching. In his 1989 Nobel Peace Prize speech, His Holiness the Dalai Lama proposed making Tibet an international ecological reserve. Vietnamese Zen monk and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh invited his followers to join the Order of Interbeing, teaching Buddhist principles using ecological examples. Zen teachers Robert Aitken in Hawaii and Daido Loori in New York examined the Buddhist precepts from an environmental perspective. Buddhist activist Joanna Macy creatively synthesized elements of Buddhism and deep ecology, challenging people to take their insights into direct action. The Buddhist Peace Fellowship, founded in 1978, added environmental concerns to its early activist agenda.

In Thailand, teak forests were being clearcut at an accelerating rate for foreign trade. This resulted in massive flooding and mudslides, generating a national wave of environmental protest. Buddhist priests in rural villages made headlines with their ritual ordination of elder trees as a symbolic gesture of solidarity with threatened forests.2 As Buddhist environmental activism spread, the "forest monks," as they came to be known, formed an ethical front in the protest against overexploitation. Other monks got involved with activist efforts to question economic development and its environmental impacts. Plastic bags, toxic lakes, and nuclear reactors were targeted by Buddhist leaders as detrimental influences on people's physical and spiritual health. In Butma, Buddhists concerned about the environment drew attention to the impacts of a major oil pipeline and the decimation of tropical forests. In Tibet, the environmental impacts of Chinese colonization were documented and publicized by support groups in the West.'

Interest in Buddhist views on the environment gained momentum in the 19905 through books, journals, and conferences. For the twentieth anniversary of Earth Day, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship produced a teaching packet and poster for widespread distribution. That same year, 1990, the first popular anthology of Buddhism and ecology writings, Dharma Gaia, was published by Parallax following the scholarly collection Nature in Asian Traditions of Thought.' World Wide Fund for Nature brought out a series of books on five world religions, including Buddhism and Ecology.' Well-established Buddhist magazines such as Tricycle, Shambhala Sun, Inquiring Mind, Turning Wheel, and Mountain Record devoted whole issues to the question of environmental practice.

In 1990 two groundbreaking national conferences were held in Seattle, Washington, and Middlebury, Vermont—both focused on eco-religious approaches to the environment. At the Vermont conference the Dalai Lama was the keynote speaker, urging people to take care of the environment. A few years later at the 1993 Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago, Buddhists gathered with Hindus, Muslims, pagans, Jews, and Christians from all over the world; one of the top agenda items was the role of religion in responding to the environmental crisis. Parallel interest in the academic community culminated in ten major conferences at Harvard Center for the Study of World Religions, purposely aimed at defining a new field of study in religion and ecology. The first of these conferences, convened by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grimm in 1996, focused on Buddhism and ecology and resulted in the first major academic volume on the subject.6

For the most part, the academic community addressed the philosophy but not the practice of Buddhist environmentalism. Applied practice was explored by socially engaged Buddhist teachers such as Thich Nhat Hanh and Bernie Glassman. In Thailand and around the world, Sulak Sivaraksa worked tirelessly for global change, and in the United Kingdom Vipas-sana teacher Christopher Titmuss ran for Parliament as a Green Party candidate. John Daido Loori committed a substantial portion of his retreat-center land in the Catskills of New York to be "forever wild," while Rochester Zen Center founder Philip Kapleau actively encouraged vegetarianism. In California, nuclear activist Joanna Macy promoted a model of experiential teaching designed to cultivate motivation, presence, and authenticity. Her workshops popularized Buddhist meditation techniques and a Buddhist view of systems thinking. Together with Buddhist rainforest activistJohn Seed of Australia, she developed the Council of All Beings to engage people's attention and imagination on behalf of all beings.' Thousands of these councils have now taken place in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Germany, Russia, and other parts of the Western world.

Since 2000 the religion and ecology movement has gathered steam and become a forceful presence at the American Academy of Religion as well as the World Council of Churches. The acceleration of global environmental problems has added to the urgency of the agenda, taken up now by Buddhists as well as Christians, Jews, and all the major religious traditions. Buddhist initiatives have been strongest in Buddhist countries such as Thailand, Tibet, and Burma. Though fewer in numbers,

Western Buddhists have contributed texts and academic study to provide a foundation for the new movement. There are now doctoral programs in the United States where a student can earn a graduate degree with a focus on Buddhism and ecology.'

RECENT STREAMS IN BUDDHIST ENVIRONMENTAL THOUGHT

As interest has developed in Buddhism and Ecology, the fields of thought have expanded through various writers as well as popular and academic discourses. When a field of thought first coalesces from wide-ranging points of engagement, a common first step is the publication of collected writings on the topic. This then opens the field to newcomers by providing an overview and introduction to the major themes within the field. For Buddhism and Ecology, this step was taken with Dharma Gaia (1990), followed by the academic collection of papers entitled Buddhism and Ecology (iç), which led to the most complete collection to date: Dharma Rain (2000). This last anthology drew together classic reference texts from a range of Buddhist traditions, along with modern commentaries, exploratory essays, and academic critiques.

With such texts available to academic audiences, professors in religious studies and environmental studies could now offer courses on Buddhism and Ecology at the undergraduate level. For students in the West, Buddhism held its own magnetic attraction as the exotic "other" next to Christianity. Young people concerned about the environment and eager for a more congruent spiritual fit with their experience in nature found Buddhist environmental thought very appealing. At a professional level, Buddhist perspectives have been a regular part of the programs organized by the Religion and Ecology Group at the American Academy of Religion." This group has seen a rapid rise in interest, with conference attendance increasing every year.

Environmental concerns have also been a significant part of inter-religious dialogue in the West. At the 2005 international conference of the Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies held in Los Angeles, the theme was "Hearing the Cries of the World," with one session focused on the "cries" of the environment. At Gethsemani II in 2002, a Catholic-sponsored dialogue in Thomas Merton's tradition, speakers addressed

structural poverty and violence resulting from global exploitation of environmental resources. Impacts of consumerism were taken up at the 2003 annual meeting of the Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies. The 2014 annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion featured numerous panels and speakers on the moral implications of climate change.

Not all topics of environmental concern have attracted attention from green Buddhists; some key issues such as climate change are only now getting attention in academic or popular discourse. Arenas requiring technical knowledge such as air and water pollution or pesticide regulation do not seem to draw much Buddhist commentary. Issues in regional or local ecosystem protection are apparently better handled by a coalition of local groups, more often nonreligious than religious. Buddhism, however, does offer rich resources for immediate application in food ethics, animal rights, and consumerism—areas that are now developing some solid academic and popular literature. The most basic Buddhist tenet of nonharming provides a strong platform for evaluating animal welfare and animal rights issues, since many of these revolve around degrees of harm to human-impacted animals, whether on factory farms or in zoos. Paul Waldau has written extensively on both Buddhist and Christian attitudes toward animals in his book The Specter of Speciesism.11

Food ethics are evolving rapidly in the West as consumers realize the tremendous costs of globally shipped goods and agriculture based on chemical inputs. In the last decade, farmers' markets and community-supported agriculture have gained great popularity and expanded quickly. Fast-food diets were deeply challenged by Eric Schlosser's research in Fast Food Nation, as well as the fast-food experiment in the movie Super-size Me. In Italy the Slow Food Movement has taken off as a celebration of cultural values for local, homemade food, especially breads, wines, and cheeses. The demand for organic produce in the West has increased steadily, and in some states such as Vermont and Oregon, organic farmers are a significant portion of the farming community. Students at Buddhist meditation retreats in the United States have come to expect high-quality, thoughtfully prepared meals. At Green Gulch Zen Center in California, students have pressed for locally grown produce of all types as well as fair-trade coffee and tea.

Interest in Buddhist food practices was perhaps ignited by one of Thich Nhat Hanh's famous exercises for mass gatherings: the orange meditation (sometimes replaced by the apple or the raisin meditation). In this long guided meditation, students practice mindfulness of touch, smell, taste, first bite, swallowing—in short, every moment in the act of eating. This meditation evoked interest in mindful food practice in general: eating slowly, eating as family practice, eating to support a healthy environment. It raised again the issue of vegetarianism, always a concern in a Buddhist setting. For Westerners exposed to both Buddhist and environmental reasons for not eating meat, ethical food practices can vary substantially."

Consumerism, the social emphasis on "stuff" and status, also lends itself well to Buddhist analysis. Since the Four Noble Truths identify desire as the cause of suffering, Buddhist practice offers useful antidotes to the runaway desire that characterizes a consumer society. In Hooked!, a number of Buddhist teachers, scholars, and practitioners take up Buddhist values, methods, and principles to address the all-penetrating tangle of consumerism that dominates social consciousness today.'3 Buddhist meditative practices are helpful in taming the impulses of desire that lead to shopping sprees and consumer addictions. Zen teachings that focus on taking apart the ego-self make a good foil to skillful marketers who specialize in identity needs. Initiatives in Thailand and Japan indicate what is possible when Buddhist grassroots organizers or temples take on the institutional structures of consumerism. 14

Buddhist environmental thought found its way into creative writing as well, in both prose and poetry. A number of Buddhist and Buddhist-leaning poets followed in Gary Snyder's footsteps, taking up subjects of nature or human-nature relations in their poetry. A collection of these poems, Beneath a Single Moon, pulled together work reflecting Buddhist environmental themes.'5 Among nature writers, several authors alluded to Buddhist practice as part of what informs their intimate relations with the landscape. Peter Matthiessen wrote eloquently of Zen insights in his book The Snow Leopard, set high in the Himalayas on a search for this rare endangered cat. Gary Snyder published two collections of essays, The Practice of the Wild and A Place in Space, which developed his Buddhist environmental thought in fresh and pragmatic ways. Gretel Ehrlich, in Islands, the Universe, Home, wrote of meditation in the open spaces of the western United States and in A Match to the Heart drew on bardo imagery to describe being hit by lightning.

ENVIRONMENTAL THEMES IN BUDDHIST TRADITIONS

Buddhists taking up environmental concerns are motivated by many fields of environmental suffering—from loss of species and habitats to the consequences of industrial agriculture. Informed by different streams of Buddhist thought and practice, they draw on a range of themes in Buddhist texts and traditions. Many of the central Buddhist teachings seem consistent with concern for the environment, and a number of modern Buddhist teachers advocate clearly for environmental stewardship. As Buddhists develop their contribution to environmental care-giving, they tend to reflect the themes and values of the teachings that are most supportive and useful to their work.

The key themes or values usually cited as foundational to Buddhist environmental thought originate with the major historical developments in Buddhism—the Theravada traditions of southeast Asia; the Mahayana schools of northern China, Japan, and Korea; and the Vajrayana lineages of Tibet and Mongolia. While Buddhists engaged in environmental work in Asian countries may draw primarily on the teachings of their region, Western Buddhists tend to take hold of whatever seems applicable to the work at hand. This list of themes is not a comprehensive review but rather an introduction to the dominant ideas in Buddhist environmental discourse today.

1] Theravada Themes

In the earliest Buddhist sutras there are many references to nature as refuge, especially trees and caves. The famous story of the Buddha's life begins with his mother giving birth under the shelter of a kindly tree. After young Gautama wandered for years in the forests of India, he took refuge at the foot of a bodhi tree, where he achieved enlightenment. For the remainder of his life, the Buddha taught large gatherings of monks and laypeople in protected groves of trees that served as rainy-season retreat centers for his followers. The Buddha urged his followers to choose natural places for meditation, free from the influence of everyday human activity. Early Buddhists developed a reverential attitude toward large trees, carrying on the Indian tradition regarding each as a vanaspati or "lord of the forest." Protecting trees and preserving open lands were

considered meritorious deeds. Today in India and Southeast Asia many large old trees areoften wrapped with monastic cloth to indicate this age-old appreciation for nature as refuge.

One of the first Buddhist teachings on the Four Noble Truths explains the nature of human suffering as generated by desire and attachment. Fully embracing the nature of impermanence, the medicine for such suffering is the practice of compassion (karuna) and lovingkindness (metta). The early Indian Jataka tales recount the many former lives of the Buddha as an animal or tree when he showed compassion to others who were suffering. In each of the tales the Buddha-to-be sets a strong moral example of compassion for plants and animals. The first guidelines for monks in the Vinaya contained a number of admonitions related to caring for the environment. For example, travel was prohibited during the rainy season for fear of killing the worms and insects that came to the surface in wet weather. Monks were not to dig in the ground or drink unstrained water. Even wild animals were to be treated with kindness. Plants too were not to be injured carelessly but respected for all that they give to people. 16

Early Buddhism was strongly influenced by the Hindu and Jain principle of ahimsa or nonharming—a core foundation for environmental concern. In its broadest sense nonharming means "the absence of the desire to kill or harm."" Acts of injury or violence are to be avoided because they are thought to result in future injury to oneself. The fourth noble truth describes the path to ending the suffering of attachment and desire—the Eightfold Path of practice. One of the eight practice spokes is right conduct, which is based on the principle of nonharming. The first of the five basic precepts for virtuous behavior is often stated in its prohibitory form as "not taking life" or "not killing or harming." Buddhaghosa explains: "Taking life' means to murder anything that lives. It refers to the striking and killing of living beings. 'Anything that lives'—ordinary people speak here of a 'living being,' but more philosophically we speak of 'anything that has the life-force.' 'Taking life' is then the will to kill anything that one perceives as having life, to act so as to terminate the life-force in it.

"8

The first precept, "not killing," applies to environmental conflicts around food production, land use, pesticides, and pollution. The second precept, "not stealing," engages global trade ethics and corporate exploitation of resources. "Not lying," the third precept, brings up issues

in advertising that promote consumerism. "Not engaging in abusive relations," interpreted through an environmental lens, can cover, many examples of cruelty and disrespect for nonhuman beings. Nonharming extends to all beings—not merely to those who are useful or irritating to humans. This central teaching of nonharming is congruent with many schools of ecophilosophy that respect the intrinsic value and capacity for experience of each being.

The Eightfold Path also includes the practice of right view or understanding the laws of causality (karma) and interdependence. The Buddhist woridview in early India understood there to be six rebirth realms: devas, asuras (both god realms), humans, ghosts, animals, and hell beings. To be reborn as an animal would mean one had declined in moral virtue. By not causing harm to others, one could enhance one's future rebirths into higher realms. In this sense, the law of karma was used as a motivating force for good behavior, including paying respect to all life. Monks were instructed not to eat meat, since by practicing vegetarianism they would avoid the hell realms and would be more likely to achieve a higher rebirth. In one sutra it is said, "If one eats the flesh of animals that one has not oneself killed, the result is to experience a single life (lasting one kalpa) in hell. If one eats the meat of beasts that one has killed or one has caused another to kill, one must spend a hundred thousand kalpas in hell ."19

A third element of the Eightfold Path, right livelihood, concerns how one makes a living or supports oneself. The early canonical teachings indicate that the Buddha prohibited five livelihoods: trading in slaves, trading in weapons, selling alcohol, selling poisons, and slaughtering animals. The Buddha promised a terrible fate to those who hunted deer or slaughtered sheep; the intentional inflicting of harm was particularly egregious, for it revealed a deluded mind unable to see the relationship between slaughterer and slaughtered. Proponents of ethical vegetarianism point out that large-scale slaughtering of animals for food production breaks the Buddhas prohibition. Some Buddhist environmentalists speak of their work as right livelihood, a path of practice that serves others and cultivates compassionate action.

Though Buddhism generally places little weight on creation stories (since there is no creator god in the Buddhist view), the Agganna Sutta contains one parable of creation in which human moral choices affect the health of the environment. In this story the original beings are described as self-luminous, subsisting on bliss and freely traveling through space. At that time it was said that the Earth was covered with a flavorful substance much like butter, which caused the arising of greed. The more butter the beings ate, the more solid their bodies became. Over time the beings differentiated in form, and the more beautiful ones developed conceit and looked down on the others. Self-growing rice arose on the Earth to replace the butter, and before long people began hoarding and then stealing food. According to the story; as people erred in their ways, the richness of the Earth declined. The point of the sutta is to show that environmental health is bound up with human morality.20 Other early suttas spelled out the environmental impacts of greed, hate, and ignorance, showing how these Three Poisons produce both internal and external pollution. In contrast, the moral virtues of generosity, compassion, and wisdom were said to be able to reverse environmental decline and produce health and purity.

2] Mahayana Themes

As Buddhist teachings were carried north to China, a number of northern schools of thought evolved, emphasizing different texts, principles, and practices, some of which have now been applied to environmental concerns. The Hua Yen school of Buddhism of seventh-century China placed particular emphasis on the law of interdependence or mutual causality. Because ecological thinking fits well with the Buddhist description of interdependence, this theme has become prominent in modern Buddhist environmental thought.2' The Hua Yen Chinese philosophy perceives nature as relational, each phenomenon dependent on a multitude of causes and conditions that include not only physical and biological factors but also historical and cultural factors.

The Avatamsaka Sutra of the Hua Yen school uses the teaching metaphor of the jewel net of Indra to represent the infinite complexity of the universe. This imaginary cosmic net holds a multifaceted jewel at each of its nodes, with each jewel reflecting all the others. If any jewels become cloudy (toxic or polluted), they reflect the others less clearly. To extend the metaphor, tugs on any of the net lines, for example, through loss of species or habitat fragmentation, affect all the other lines. Likewise, if clouded jewels are cleared up (rivers cleaned, wetlands restored), life

across the net is enhanced. Because the net of interdependence includes not only the actions of all beings but also their thoughts, the intention of the actor becomes a critical factor in determining what happens.

The law of interdependence suggests a powerful corollary, sometimes translated as "emptiness of separate self." Since all phenomena are dependent on interacting causes and conditions, then nothing exists as autonomous and self-supporting. This Buddhist understanding and experience of self contradicts the traditional Western sense of self as a discrete autonomous individual. Interpreting the Hua Yen metaphor, Gary Snyder suggests that the empty nature of self offers access to "wild mind," the energetic forces that determine the nature of life." These forces act outside of human influence, setting the historical, ecological, and even cosmological context for all life.

T'ien-t'ai monks in eighth-century China believed in a universal Buddha nature that dwelled in all forms of life. Sentient (animal) and non-sentient (plant) beings and even the Earth itself were seen as capable of achieving enlightenment. This concept of Buddha nature is closely related to Chinese views of chi or moving energy, ever changing, taking new form. This view of nature reflects a dynamic sense of flow and interconnection between all beings, with Buddha nature arising and changing constantly. Buddhist scholar Ian Harris suggests that a Mahayana vegetarian ethic was first formulated around the idea of Buddha nature. In the Mahaparinirvana Sutra Buddha nature is understood to be an embryo of the Tathagata or the fully enlightened being.23 Addressing the ethics of meat eating, Western Zen teacher Philip Kapleau wrote, "It is in Buddha-nature that all existences, animate and inanimate, are unified and harmonized. All organisms seek to maintain this unity in terms of their own karma. To willfully take life, therefore, means to disrupt and destroy this inherent wholeness and to blunt feelings of reverence and compassion arising from our Buddha mind." 14 Taking an animal's life, therefore, is destructive to the Buddha nature within the animal to be eaten. Kapleau taught that to honor the Tathagata and the potential for awakening, one should refrain from eating meat.

Environmental advocates sometimes call themselves "ecosattvas," those who take up a path of service to all beings. They are following the Mahayana model of the enlightened being or bodhisattva who returns lifetime after lifetime to help all who are suffering. Where the early

Theravada schools emphasized achieving enlightenment and leaving the world of suffering, the northern schools, influenced by Confucian social codes, placed great value on becoming enlightened to serve others. The bodhisattva vow to "save all sentient beings" calls for cultivating compassion for the endless suffering that arises from the fact of existence. Such bodhisattva acts of environmental service are marked by a strong sense of intention that reflects a Buddhist virtue ethic.25 Environmentalists apply this ethic to plant and animal relations as well as to people and societies, promoting environmental stewardship as a path to enlightenment.

Monastic temples in the Ch'an traditions of China were often built in mountainous or forested places. Chinese poets from the fifth century on accumulated an extensive body of literature reflecting a spiritual sense of belonging to wild nature on a cosmological level." Japanese schools of Zen influenced haiku and other classic verse forms that cultivated a sense of oneness with nature in the moment. Dogen, founder of the Soto sect of Zen, spoke of mountains and waters as sutras themselves, the very evidence of the dharma arising.27 He taught a method of direct knowing, experiencing this dharma of nature with no separation. For DOgen, the goal of meditation was nondualistic understanding, or complete transmission between two beings. Dogen taught that much human suffering generates from egoistic views based in dualistic understanding of self and other. To be awakened is to break through these limited views (of plants and animals) to experience the self and myriad beings as one energetic event.

3] Vajrayana Themes

Tibetan schools drew on all of the historic teachings transmitted to the far north from China, India, and Southeast Asia. Kindness for others was emphasized strongly with the encouragement to treat all sentient beings as having been their mother in a former life. In Santideva's classic eighth-century text on the bodhisattva path, the practice of compassion for all beings becomes world transforming. He vows: "Just like space and the great elements such as Earth, may I always support the life of all the boundless creatures. And until they pass away from pain, may I also be the source of life for all the realms of varied beings that reach unto the ends of space.""

For indigenous Tibetans, the landscape was seen as a sacred mandala, a symbolic representation of Vajrayana teachings. Monks and others

for many centuries have gone on pilgrimage to specific mountains to demonstrate their spiritual devotion, sometimes taking years, to complete their journeys. Heaps of inscribed prayer stones are placed along stone mountain paths, and prayer flags stream in the winds, offering encouragement to pilgrims traversing the sacred lands. Stupas, or relict shrines, are placed at significant points on the land to draw energy and commemorate important religious leaders. Pilgrims make offerings at these sites, linking the points of energy across the landscape with their own footsteps.29

4] Contemporary Themes

Today's Buddhists have drawn on a number of the principles above as supportive teachings for environmental work. Several additional themes have also been popularized by modern Buddhist teachers and practitioners. Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh promotes mindfulness as a central stabilizing practice for calming the mind and being present. He works with the teachings of the Satipatthana Sutta, providing instructions in mindfulness of body, feelings, mind, and objects of mind, linking these directly with the most basic actions of eating and walking. Thich Nhat Hanh is one of a handful of Buddhist teachers today who has offered retreats for environmentalists. His word interbeing has become popular among Western Buddhists as a way to express the dynamic sense of relationship with the Earth. He frequently teaches about interbeing through the example of a piece of paper, which holds the sun, the Earth, the clouds, and all the beings of the forest.3° Mindfulness practice in Buddhist retreat centers supports thoughtful food practices, from organic gardening to silent cooking.

Environmentally engaged Buddhists are concerned about the ecological consequences of harmful human activities. Buddhist scholar Kenneth Kraft has proposed the term eco-karma to cover the multiple impacts of human choices as they affect the health and sustainability of the Earth.31 An ecological view of karma extends the traditional view of karma to a general systems view of environmental processes. Eco-karma might be expressed, for example, as one's ecological footprint—the amount of land, air, and water required for food, water, energy, shelter, and waste disposal. Tracing such karmic streams across the land is one way to understand the human responsibility for environmental stewardship.

Among today's Buddhists, environmental work is regarded as a form of social activism, a practice with a component of advocacy for social change. Activism such as this is called socially engaged Buddhism, a practice path mostly outside the gates of the monastery. Taking up environmental work in this way, there is no sense of separation between the activist work and one's practice. Caring for the environment becomes a practice that engages one fully in the core Buddhist practices. Teaching others about the ecological problems and solutions in this context can be seen as a kind of dharma teaching, offered in the spirit of liberating humans from the suffering they are creating for the Earth and themselves. Socially engaged Buddhists have taken up the concerns of nuclear waste, animal factory farming, and consumerism, among others. By working with other Buddhist activists, Buddhist environmentalists gain support in keeping Buddhist practice and philosophy at the heart of their work.

A ROLE FOR BUDDHISM IN THE ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS

Will green Buddhist activists play a significant role in addressing the multitude of environmental problems in need of creative solutions? Will scholars of Buddhist environmental thought contribute useful insights to understand human motivation and behavior? Will Buddhist priests and teachers take up environmental concerns as part of their work with students and local communities? How will Buddhism stack up compared with other world religious traditions in affecting the outcome of unsustainable environmental trends? This section reviews the strengths and limitations that are apparent at this early stage of Buddhist environmental engagement, looking at three arenas of activity. Because the field of Buddhism and ecology is evolving at a rapid rate, much more may yet be drawn from the Buddhist teachings and be of help in sorting through the difficult environmental choices that lie ahead.

1] Strengths

How effective is Buddhist environmental action? And what might make Buddhist environmentalism distinctive from other environmental or eco-religious activism? Let us consider the role for activists and what strengths from Buddhism they might bring to bear on their work. First

and perhaps most obvious, to others, Buddhist activists would ground their work in regular engagement with Buddhist practice forms. Thich Nhat Hanh, for example, has encouraged activists to recite the precepts together to reinforce guidelines for right conduct in the midst of challenging situations. Walking meditation is taught regularly as part of activist retreats at Vallecitos Mountain Refuge in New Mexico and 'Whole Thinking retreats in Fayston, Vermont.32 Practicing with the breath can help sustain activists under pressure in the heat of a conflict. At Green Gulch Zen Center, Earth Day celebrations have been woven into the public event for Buddha's birthday. Environmental activists associated with the Buddhist Peace Fellowship include meditation as part of their regular meeting activities.

Buddhist texts recognize a strong relationship between intention, behavior, and the long-range effects of action. Clarifying one's intention in advocacy work helps prevent a sense of being overwhelmed or burnout. Environmental issues are rarely small and self-contained; one problem leads to another, and many parties are often involved in negotiating a lasting solution. Campaigns or public hearings can be toxic with frustration, anger, and power displays. The Buddhist activist may be able to carry some emotional stability in the face of this heated energy by maintaining clear intention, holding to the bodhisattva vow to reduce suffering and help all beings. This can help other activists clarify their motivation and set the stage for more effective collaboration and division of tasks.

Central to Buddhist teaching is the focus on breaking through the delusion of the false self, the ego that sees itself as the center of the universe. One antidote for this universal human tendency is the practice of detachment. A green Buddhist approach to activism would include some healthy ego-checking work to see if the activist is motivated by a need to build his or her ego identity as an environmentalist or Earth saver. Keeping intention strong but letting go of the need for specific results is a practice in detachment. One recognizes that the outcome of any situation will depend on many factors, not just the contributions of one person. Being receptive to the creative dynamics at play and less identified with a particular end result can produce surprising collaborations. Sulak Sivaraksa calls this "small b Buddhism"—downplaying the ego of being a good Buddhist in favor of being an effective friend to others working toward a common goal.33

Key to a Buddhist approach to problem solving is taking a nondualistic view of reality. This follows from an understanding of self as not separate from all others but rather dynamically co-created. Most environmental battles play out as confrontations between seeming enemies: tree huggers versus loggers, housewives versus toxic polluters, organic farmers versus corporate seed producers. From a Buddhist perspective, this kind of demonizing destroys spiritual equanimity; it is far preferable to act from an inclusive standpoint, listening to all parties involved rather than taking sides. This approach has traditionally been quite rare in environmental problem solving but is becoming more common now as people grow weary from the dehumanizing nature of enemy making. In a volatile situation, a Buddhist commitment to nondualism can help stabilize negotiations and work toward long-term functional relationships.

Buddhist practice is grounded in the fundamental vow of taking refuge in the Three Treasures: the Buddha or teacher, the Dharma or teachings, and the Sangha or practice community. Asian activists usually base their work in relations with local sanghas as an effective grassroots base for accomplishing change. Western Buddhists, handicapped by the Western emphasis on individualism, tend to value sangha practice as the least of the Three Treasures. They tend to be drawn first to the calming influence of meditation and the moral guidelines of the precepts. Practicing with community can be difficult for students living some distance from Buddhist centers and surrounded by a predominantly Judeo-Christian culture. Building community is crucial for Buddhist environmentalists even though they are geographically isolated from each other and sometimes marginalized by their own peers in Buddhist centers. This has been mitigated substantially by internet organizing, and now, for example, the Green Sangha based in the San Francisco area has an international presence through its existence on the web.34

Second, let us consider the role for scholars of Buddhist environmental thought and what aspects of Buddhism might inform their work. This new academic field has engaged both traditional scholars who study but do not practice Buddhism as well as those who both study and practice, the scholar-practitioners. Each has strengths to contribute in growing the field of knowledge. Traditional scholars can bring an objective view, placing environmental perspectives in the broader field of Buddhist studies, helping to legitimize these discussions. Academics such as

Ian Harris and Alan Sponberg have made such contributions, raising questions about popular green Buddhism and providing accurate historical background.35 Scholar-practitioners such as Rita Gross and Kenneth Kraft bring an experiential understanding of the teachings of their lineages to complement their academic training.36 Scholar-practitioners are generally more comfortable and clear about their intention in doing environmental academic work, that it is motivated by their bodhisattva vows, for example. However, their work is sometimes challenged by academics who imply that "arm's length" engagement in one's scholarly pursuits is not possible for practitioners.

Scholars of either persuasion can bring their well-trained minds and analytic skills to critiquing green Buddhism and challenging ungrounded idealistic interpretations. As Buddhism grows in popularity in the West, it is vulnerable to mistaken views, blurred with New Age ideas of individually designed spirituality. Scholars grounded in the original texts can check emerging ideas for distortions of Buddhist thought. Tibetan Buddhist texts and training are particularly strong in methods of analysis. Judith Simmer-Brown uses these to understand the "empty" nature of globalization and the possibility for other forms of sustainability to arise.37 Ian Harris has examined the popular interpretation of Buddhism as the most environmentally friendly of the world religions, arguing that the historical record shows much more ambivalence.38 Scholars of Buddhist environmental thought are also in a good position to critique the tenets of monotheistic traditions that act as a deterrent to seeking a sustainable future. Rita Gross, for example, has questioned the strong pronatalist positions of the Christian church as problematic in dealing with exponential population growth and its impacts on the planet.39

The strength of academic work in Buddhist environmental thought lies in legitimizing this new field in the eyes of traditional schools of religion and philosophy. Thus far the list of academic volumes addressing environmental concerns from a Buddhist perspective is still fairly small. Though Buddhist insights are usually included in pan-religious commentaries on the environment, entire volumes by single or multiple Buddhist scholars are quite rare. It is likely that new work will build on the first round of anthologies and take up specific aspects of environmental concern, as Hooked! has done with consumerism. Topics that already lend themselves to academic analysis such as food ethics and animal rights concerns may be the next work to emerge from the greening ivory tower.

What about Buddhist priests, monks, teachers? What strengths do they bring to environmental discourse and action? East or West, ordained Buddhists often are in leadership positions within their local temples. As leaders they can adapt the practice forms to new settings, including concern for the planet as part of their community responsibility. One Zen teacher served only bread and water for a day during a weeklong retreat, using this as a springboard to raise issues of poverty and inequity around the world. Another teacher regularly holds ceremonies for victims of major disasters such as Hurricane Katrina or the earthquake in Pakistan in 2005. Several lay teachers have developed practice forms that take place in the garden to incorporate the presence of plants in memorial ceremonies. One Japanese Pure Land priest has galvanized his entire sangha to place solar panels on the roof of the temple to help reduce global climate change.

Buddhist centers that interface with the public can serve as models of environmentally sustainable practices .40 Through architectural design choices and monastic example, visitors can see the possibilities for energy and water conservation. Through exposure to mindful kitchen practice, retreatants can learn about the food they eat and its origins. The leadership role of the head priest or teacher is often necessary for environmental concerns to be emphasized in everyday practice. Where a Buddhist teacher has shown environmental commitment, the centers tend to reflect that commitment. When Vermont Zen Center added a new dining hall and housing wing, head teacher Sunyana Graef led the effort to follow green building principles. With her support, the grounds were transformed through extensive volunteer efforts from community members, returning trees to a suburban lawn and cultivating spaces for thoughtful reflection (such as the lovely Jiso rock garden). In New York, John Daido Loori and his students at Zen Mountain Monastery lead summer canoeing and wilderness programs in the Adirondacks to deliberately place students in contact with the forces of nature. This has been a hallmark of the center, and Daido honored his concern for the pristine northern mountains by purchasing a piece of lakeshore where students can monitor water quality.

More and more, experienced Buddhist teachers are being asked to provide meditation instruction for environmental advocates. When the ecosattva chapter of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship prepared for protests against old-growth redwood logging in Northern California, they trained at Green Gulch Zen Center. When high-ranking executives in the Trust for Public Land sought to revitalize their commitment to land-conservation values, they developed staff meditation retreats at Vallecitos Mountain Refuge. Thus far; Buddhist practice techniques have been applied much more extensively to hospice and healthcare settings, prison work, and AIDS assistance. But, bit by bit, the work with environmental issues is adding up. In the West, Buddhist meditation instruction is perceived to be neutral training available for people of any faith or secular persuasion. It is generally not seen as proselytizing. Environmentalists who tend to reject organized religion and find spiritual fulfillment in the outdoors are open to Buddhist support for their environmental aims. The possibility of this work first emerged in a retreat for environmentalists organized by Thich Nhat Hanh's followers at Ojai, California, in 1993. Thich Nhat Hanh oriented the retreat around taking care of the environmentalists, sensing that burnout was rampant for those driven by concern for the plight of so many suffering beings and places.

2] Limitations

So far this would appear to be a rosy picture, filled with useful options for Buddhists interested in supporting environmental action. But critics have already pointed out significant barriers to any extended Buddhist influence in environmental work, at least in the West. One philosophical problem is that there is no single view of nature or environment that crosses all the Buddhist traditions. David Eckel has described in some detail the difference in Indian Buddhist views of nature compared with Japanese views, for example. These views represent very different time periods and cultures; Eckel finds it problematic that Westerners looking for the "green" in Buddhism blur over these major distinctions.41 Some have called this process "mining" the tradition for what you want from it, a common human tendency among all the religious traditions, not so different than what is done to support fundamentalist Christian interpretations. Green Buddhism could suffer from the same sort of myopic views unless it encourages further understanding of Buddhism itself.

Further, Buddhism is not a nature religion per se, as are pagan or Native American traditions that base their spiritual understandings on relations with the land and its living beings. The central principles of Buddhism deal with human suffering and liberation from that suffering; the process of insight awareness is not dependent on the land or any physical forms. It is much more of a mental process, cultivating capacities in the human mind. Thus, at its roots, Buddhism does not immediately lend itself to environmental concern. In fact, since the Buddhist approach can work within any situation, environmental sustainability is not necessarily a prerequisite or,a goal for liberation practice. The practice of detachment to hobble the power of desire could actually work against such environmental values as "sense of place" and "ecological identity."

Alan Sponberg critiques the green Buddhist emphasis on interdependence, suggesting that green Buddhists may be stepping too far away from the core spiritual development challenges in Buddhist training.42 Though the law of interdependence interfaces very well with similar laws of ecology, this alone is not enough, in his opinion, to lead a practitioner to enlightenment. Ian Harris critiques Joanna Macy for taking the metaphor of Indra's jeweled net too far and missing the original teaching emphasis, which was on karma, not ecology. He is wary of Buddhist activists who interpret key Buddhist principles too narrowly, from only an environmental point of view. For Harris, the project of "saving the world" is not a central concern, and dragging Buddhist concepts into the process may not be necessary or even helpful. He joins Eckel and Lambert Schmidthausen in exposing the lack of concern for animals and nature in many of the Pali Canon texts.43

To this point, green Buddhism has only taken up specific environmental problems primarily in countries that already have a significant Buddhist population. Thai forest monks and Sulak Sivaraksa's Grassroots Leadership Training Program have gained some footing in protesting lake pollution, fish die-offs, and clearcutting of forests. Tibetans in exile in India have been able to undertake environmental education programs with local Tibetans, but they have had virtually no impact on the rampant exploitation of Tibet's natural resources by the Chinese. In the West, green Buddhists such as the Green Sangha have taken on energy conservation and recycling as everyday actions, but their impact has been fairly local. Green Buddhists have not yet been significant players in some of

the Western interfaith environmental initiatives which are making a difference: the global Jubilee Debt forgiveness campaign, religious advocacy for corporate social responsibility through stockholder actions, and the Interfaith Power and Light movement for alternate energy purchasing. This is partly because green Buddhists are still so few in number, but it may also be because Buddhism as a tradition does not carry the same charge for social justice as the monotheistic traditions. Righting environmental wrongs is often a situation of injustice for those who are harmed, whether plants, animals, ecosystems, or people. Buddhist virtue ethics do address these wrongs, but not with the same fire as Judaism and Christianity.

A further critique of green Buddhism in the West is that it has had so little influence solving real environmental problems in Buddhist countries. For most people it is local environmental problems that catch their attention; possibilities for local action seem more accessible than those on a global scale. As a consequence, few Westerners are actively working to stop or reverse environmental devastation in the countries that spawned their beloved religion. Some members of Buddhist Peace Fellowship have joined in solidarity with the International Network of Engaged Buddhists on their environmental campaigns. But for the most part it is difficult for Westerners to engage Asian problems from afar and from a different cultural perspective. For some Asians, Westerners are seen as part of the problem, due to their disproportionate consumption of planetary resources.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, interest in Buddhist environmental thought and action is very strong in both the West and East. Misinterpretations, mistaken views, and idealized projections are perhaps inevitable for any young movement as it takes shape. At this point the environmental movement itself is so well established in large and small nonprofit advocacy groups, in state and federal legislation, and in campus sustainability actions that it hardly needs a Buddhist contribution. But in small supportive ways it may be that Buddhism will yet take its place in shaping the direction of environmental problem solving around the globe.

CONCLUSION

Buddhist environmental thought is both ancient and brand new. While many Buddhist principles handed down from centuries ago seem broadly

applicable to environmental concerns, articulating those applications is still a very new project of the last few decades. Scholars of Buddhist environmental thought have many topics yet to address. Green Buddhist activists have barely begun to make a unified impact. This is a movement of both thought and action to track over the next few decades.

Has a Buddhist environmental movement coalesced around the globe? Not at all. Only a tiny handful of organizations have been formed to promote Buddhist environmental views and approaches. No clearly defined environmental agenda or set of principles has been agreed upon by any group of self-identified green Buddhists. All this is perhaps too much to expect of a fledgling movement. It may yet be that in ten years many more books will have been published offering Buddhist views regarding environmental concerns. It may yet be that green Buddhist centers will be established for the express purpose of fostering environmental sus-tainability, a sort of green Catholic Worker house model. As more and more serious students in the West become teachers and temple leaders, some may take up leadership roles cultivating mindfulness around environmental issues.

What is completely unknown is what larger forces and events will shape all environmental concern and activity. In 2005 and then again in 2017 the record number of hurricane-strength storms generated more environmental disasters than communities could handle effectively. Global climate change, the shrinking supply of oil, and the lack of available drinking water may be much more powerful forces shaping human behavior than any religious tradition. All this is yet to unfold. But certainly Buddhists of all traditions and cultures would be welcome to join the much-needed efforts to turn the tide from further planetary destruction.

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

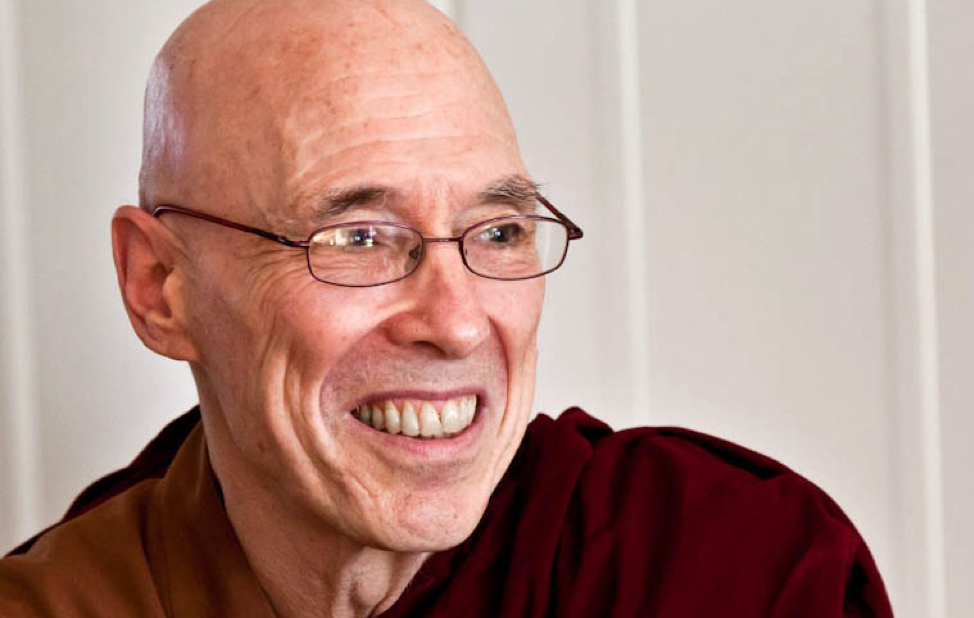

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, originally from New York City. He received novice ordination in 1972 and full ordination in 1973 and lived in Asia for 24 years, primarily in Sri Lanka. A Buddhist scholar and translator of Buddhist texts,

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, originally from New York City. He received novice ordination in 1972 and full ordination in 1973 and lived in Asia for 24 years, primarily in Sri Lanka. A Buddhist scholar and translator of Buddhist texts,