2022/08/02

[[The I Ching or Book of Changes - Richard Wilhelm (133p version) downloaded

[[The I Ching or Book of Changes by Richard Wilhelm, C. G. Jung |

The I Ching or Book of Changes by Richard Wilhelm, Cary F. Baynes, Hellmut Wilhelm, C. G. Jung

Uploaded byMlopez

Date uploaded

on Mar 28, 2022

Full description

You are on page 1of 811

The Numerology of the I Ching by Taoist Master Alfred Huang - Ebook | Scribd

Start reading

Remove from Saved

Add to list

Download to app

Share

The Numerology of the I Ching: A Sourcebook of Symbols, Structures, and Traditional Wisdom

By Taoist Master Alfred Huang

4/5 (7 ratings)

301 pages

5 hours

Included in your membership!

at no additional cost

Description

The first book to cover the complete Taoist teachings on form, structure, and symbol in the I Ching.

• Provides many new patterns and diagrams for visualizing the layout of the 64 hexagrams.

• Includes advanced teachings on the hosts of the hexagrams, the mutual hexagrams, and the core hexagrams.

• Written by Taoist Master Alfred Huang, author of The Complete I Ching.

The Numerology of the I Ching is the first book to bring the complete Taoist teachings on form, structure, and symbol in the I Ching to a Western audience, and it is a natural complement to Alfred Huang's heralded Complete I Ching. It examines not only the classic circular arrangement of the eight trigrams but also the hidden numerology in this arrangement and its relationship to tai chi and the Chinese elements. Huang explains the binary code underlying the I Ching, the symbolism behind the square diagram of all 64 hexagrams, and Fu Xi's unique circular layout of the 64 hexagrams, completely unknown in the West. Entire chapters are devoted to such vital material as the hosts of the hexagrams, the mutual hexagrams, and the core hexagrams--all barely hinted at in previous versions of the I Ching. With appendices listing additional symbolism for each hexagram, formulas for easily memorizing the Chinese names of the sixty-four hexagrams, and much more, The Numerology of the I Ching is a must for serious I Ching students.

Body, Mind, & Spirit

Self-Improvement

All categories

Read on the Scribd mobile app

Download the free Scribd mobile app to read anytime, anywhere.iOS

Android

PUBLISHER:

Inner Traditions

RELEASED:

Jul 1, 2000

ISBN:

9781594775666

FORMAT:

Book

About the author

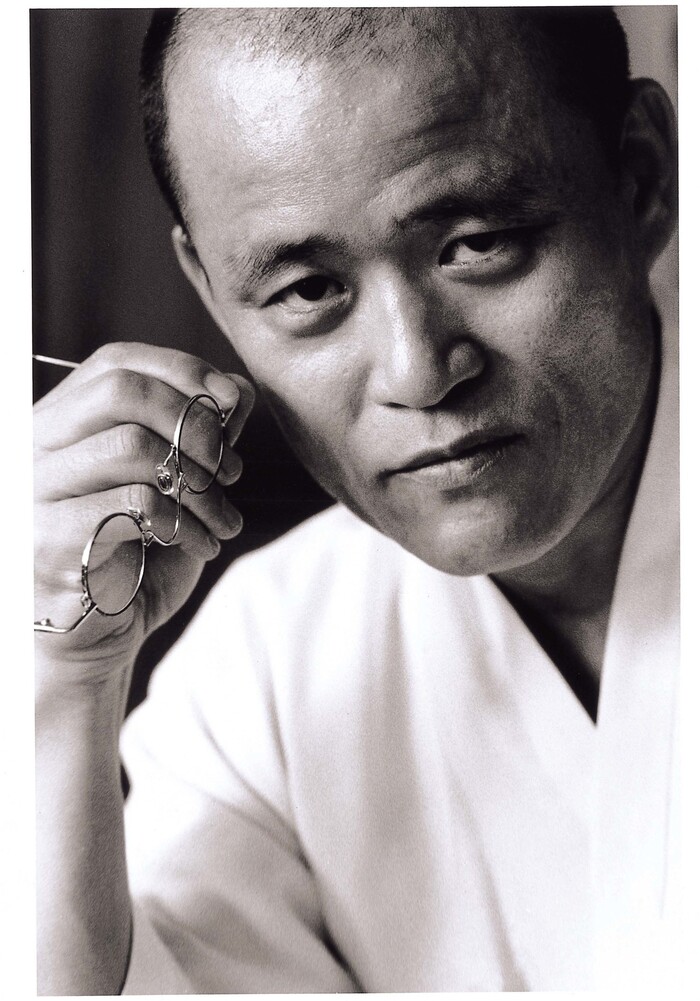

Taoist Master Alfred Huang

Taoist Master Alfred HuangA third-generation master of Wu style Tai Chi Chuan, Chi Kung, and Oriental meditation, Master Alfred Huang is a professor of Taoist philosophy who studied the I Ching with some of China’s greatest minds--only to be imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution in 1966 and sentenced to death. For 13 years in prison Master Huang meditated on the I Ching and found the strength to survive. Released in 1979 weighing only 80 pounds, he emigrated to the United States. Master Huang is the founder of New Harmony, a nonprofit organization devoted to teaching self-healing, and is the author of The Numerology of the I Ching and Complete Tai-Chi. He lives on the island of Maui.Read more

Related to The Numerology of the I Ching

Related Books

Skip carousel

Carousel Next

Feng Shui NumerologybyJaspal Singh Gaidu

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars(4/5)

I Ching The Book of Answers: The Profound and Timeless Classic of Universal WisdombyWei Wu

Rating: 1 out of 5 stars(1/5)

I Ching Readings: Interpreting the AnswersbyWei Wu

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars(4/5)

Yi Jing: The True Images of the Circular Changes (Zhou Yi) Completed by the Four SagesbyAlexander Goldstein

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars(3/5)

The Living I Ching: Using Ancient Chinese Wisdom to Shape Your LifebyMing-Dao Deng

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars(3/5)

The Laws of Change: I Ching and the Philosophy of LifebyJack M. Balkin

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

The I Ching for Writers: Finding the Page Inside YoubySarah Jane Sloane

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

Oracle: The I Ching for everyday usebyPéter Müller

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

Taoist Astrology: A Handbook of the Authentic Chinese TraditionbySusan Levitt

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars(3/5)

Original I Ching: An Authentic Translation of the Book of ChangesbyMargaret J. Pearson

Rating: 0 out of 5 stars(0/5)

Lillian Too’s Flying Star Feng Shui For The Master PractitionerbyLillian Too

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars(3/5)

The Occult I Ching: The Secret Language of SerpentsbyMaja D'Aoust

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

The Complete I Ching — 10th Anniversary Edition: The Definitive Translation by Taoist Master Alfred HuangbyTaoist Master Alfred Huang

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

The I Ching WorkbookbyWei Wu

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

Cosmic Astrology: An East-West Guide to Your Internal Energy PersonabyMantak Chia

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars(4/5)

I Ching Wisdom Volume One: Guidance from the Book of AnswersbyWei Wu

Rating: 0 out of 5 stars(0/5)

The Jade Emperor's Mind Seal Classic: The Taoist Guide to Health, Longevity, and ImmortalitybyStuart Alve Olson

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars(3/5)

I Ching Made Easy: Be Your Own Psychic Advisor Using the Worold's Oldest OraclebyAmy M. Sorrell

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars(3/5)

I Ching Life: Becoming Your Authentic SelfbyWei Wu

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars(4/5)

A Tale of the I Ching: How the Book of Changes BeganbyWei Wu

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

Lillian Too’s Irresistible Feng Shui Magic: Magic and Rituals for Love, Success and HappinessbyLillian Too

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars(4/5)

Taoist Feng Shui: The Ancient Roots of the Chinese Art of PlacementbySusan Levitt

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars(4/5)

Four Pillars of Destiny: Potential, Career, and WealthbyJerry King

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars(4/5)

Secrets of Chinese Divination: A Beginner's Guide to 11 Ancient Oracle SystemsbySasha Fenton

Rating: 0 out of 5 stars(0/5)

I Ching Wisdom Volume Two: More Guidance from the Book of AnswersbyWei Wu

Rating: 0 out of 5 stars(0/5)

I ChingbyCSPtrade2

Rating: 0 out of 5 stars(0/5)

Feng Shui: The Living Earth Manual: The Living Earth ManualbyStephen Skinner

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars(5/5)

Related Podcast Episodes

[도올김용옥] 도올주역강해 3강 - 주역점에 필요한 4가지, 괘상 괘명 괘사 효사 - '역경'은 공자의 작이 아니...

[고명섭 기자] 도올 “주역은 하늘의 뜻을 묻고 듣는 것” :한겨레

등록 :2022-07-29

고명섭 기자

철학자 김용옥 ‘주역’ 해설서

역경 ‘64괘 384효’ 상세한 풀이

동주 혼란기 성립 ‘깊은 우환의식’

동아시아 윤리학·형이상학 창출

도올 주역 강해

김용옥 지음 l 통나무 l 3만9000원

<주역>은 동아시아 문명의 바탕을 이루는 경전 가운데 가장 난해한 텍스트로 꼽힌다. 주역에 관해 여러 주해서를 쓴 신유학의 대사상가 주희도 <주역>을 읽고 ‘정말로 해석하기 어렵다’(최난간, 最難看)고 했다. 그런데도 이 경전에 담긴 음양론은 동아시아 세계관에 결정적인 영향을 주었고, 고대 이래 동아시아인의 일상을 지배하다시피 했다. <도올 주역 강해>는 철학자 김용옥 전 고려대 교수가 쓴 <주역> 해설서다. 지은이는 지난 2천여년 동안 동아시아에서 탄생한 주요한 <주역> 해석을 바탕에 깔고서 이 난해한 책을 오늘의 언어로 바꾸어 우리 시대를 이해하는 데 빛을 주는 책으로 빚어낸다.

<주역>이란 ‘주나라에서 성립한 역’이라는 뜻이다. 이때 ‘역’(易)은 일차로 변화를 뜻한다. 그래서 서양에서는 <주역>을 ‘변화의 책’(The Book of Changes)이라고 번역한다. 동시에 <주역>은 점치는 책이다. 주희가 “대저 ‘역’이란 복서(점) 책자에 지나지 않는다”고 말한 이유도 여기에 있다. <주역>은 변화의 책이자 변화를 점치는 책이다. <주역>이라고 부르는 이 책자는 <역경>과 <역전>으로 이루어져 있다. <역경>은 <주역>을 구성하는 핵심 텍스트이며 <주역> 성립 역사상 가장 오래된 문헌이다. <역전>이란 공자 이후 이 <역경>을 해설한 권위 있는 논문들을 가리킨다. <단전> <상전> <문언전> <계사전> <설괘전> <서괘전> <잡괘전> 7종이 <역전>을 이룬다. 주희가 ‘역’이라고 부른 것은 이 문헌들 가운데 핵의 자리에 놓인 <역경>을 가리킨다. 이 <역경>의 내용을 철학적으로 해석한 논문들이 <역전>으로 덧붙여져 현재의 <주역>이 된 것이다.

<주역>은 우주 만물과 인간 세계의 변화를 이야기하는 책이다. 이 변화를 설명하는 데 쓰이는 범주가 음과 양이다. <주역>은 이 두 범주를 조합해 천지의 모든 것을 설명한다. 주목할 것은 이 두 범주가 절대적으로 구별돼 있는 것이 아니라는 사실이다. 양 속에 음이 있고 음 속에 양이 있다. 양이 음으로 바뀌고 음이 양으로 바뀐다. 이렇게 음양이 서로 바뀌어감으로써 세상 모든 것이 변화 속에 있게 된다. 그러나 이 변화는 일직선의 변화가 아니라 순환하는 변화다. 우주는 끝이 있으므로 그 한계 안에서 모든 것이 무수한 변화를 거쳐 제자리로 돌아오는 것이다. 봄 여름 가을 겨울의 사계절이 순환하는 것과 같다. 한번은 양으로 한번은 음으로 바뀌는 이 ‘일양일음’의 변화는 우주의 법칙일 뿐만 아니라 인간 세상의 법칙이기도 하다. 이 음양론은 17세기 중국에 온 서방 선교사를 통해 독일 철학자 라이프니츠에게 알려졌고, 라이프니츠는 이 음양론의 영향을 받아 오늘날 컴퓨터 이진법의 기원이 되는 수의 체계를 창안했다.

<도올 주역 강해>를 펴낸 도올 김용옥 전 고려대 교수. 도올은 <주역>을 ‘하늘의 소리를 듣는 책’이라고 말한다. 통나무 제공

<역경>은 이 음양의 변화 양상을 점으로써 알아보는 책이다. 그 <역경>을 구성하는 기초 단위가 ‘괘’와 ‘효’다. 효는 음효(- -)와 양효(―)로 나뉘는데, 지은이는 이 음효와 양효가 각각 남녀의 성기를 상징한다고 본다. 이 두 효가 여섯개 쌓여 하나의 괘를 이루고, 이 괘가 64개 모여 전체를 이룬다. 가령, 양효만 여섯개 쌓이면 ‘건 괘’(첫번째 괘)가 되고, 음효만 여섯개 쌓이면 ‘곤 괘’(두번째 괘)가 된다. 이렇게 쌓여 이룬 ‘괘’의 모양을 ‘괘상’이라 한다. 이 괘상마다 괘의 이름인 ‘괘명’이 있고, 그 괘를 설명하는 말씀 곧 ‘괘사’가 따른다. 각각의 괘에는 여섯개의 효가 있으므로 전체 64괘는 384효로 이루어진다. 이 384개의 효마다 효사가 달려 있다. 특정한 절차를 통해 효를 뽑아내고 그 효에 달린 효사를 읽어 길흉을 알아보는 것이 바로 역점이다. 이 책은 그 절차 곧 점치는 방법도 상세히 알려준다.

그렇다면 점을 친다는 것은 무엇을 뜻하는가? 지은이는 먼저 ‘역’은 ‘기복의 대상’이 아님을 강조한다. “인간의 운명이나 운세라는 것은 내 실존의 문제이지 점으로 해결될 수 있는 것이 아니다.” 그렇다면 왜 점을 치는가? 지은이는 “내 지력이나 노력으로 선택의 기로가 열리지 않는 극한 상황에서 하느님의 소리를 듣는 것”이 점을 치는 이유라고 말한다. 점이 가리키는 효사는 하느님이 내려주는 말씀이다. 이때의 하느님은 어떤 초월적 절대자가 아니라 음양의 기운 속에 운행하는 우주 만물에 깃든 하느님이라고 지은이는 말한다. 바로 이 하느님과 대화하는 것이 점이다. 주역이 발흥한 시기는 동주시대(기원전 770~256)의 혼란기였다. 세상이 끝없이 어지러웠기에 주역에는 깊은 ‘우환의식’이 배어 있다. 세상을 걱정하는 마음으로 어떤 결정을 내려야 할지 알 수 없을 때 기대는 것이 점이라는 방식의 ‘물음’이었다. 그러므로 점은 실존의 한계상황, 시대의 한계상황에서 하늘에 뜻을 묻는 것이라고 할 수 있다. 사사로움을 넘어선 물음과 응답이었기에, 후대에 역에 대한 해석을 통해 철학적·윤리학적·형이상학적 사유가 자라날 수 있었다.

이 책은 64개의 괘를 그 효와 함께 하나하나 상세히 설명한다. 이 64괘 가운데 63번째에 놓인 괘가 ‘기제’(旣濟)이고 64번째에 놓인 괘가 ‘미제’(未濟)다. 기제란 ‘이미 건넜다’는 뜻이고 미제란 ‘아직 건너지 못했다’는 뜻이다. 왜 <역경>의 마지막 괘가 ‘완료’를 뜻하는 기제가 아니라 ‘미완’을 뜻하는 미제일까? 역의 세계에는 완전한 종결이 없기 때문이다. 끝은 항상 시작을 품고 있는 것이기에 미제가 마지막에 놓인다. “역의 논리에 즉해서 생각하면 기제 다음에 미제라는 것은 이미 끝난 것이 아니라 아직 끝나지 않았다는 것, 즉 이제 다시 시작이라는 뜻을 내포한다.” 이 미제는 그 표면의 뜻만 보면 긍정적인 것이 아니다. 세번째 효의 효사는 ‘정흉(征凶), 이섭대천(利涉大川)’이다. 그 함의를 풀어보면 ‘흉운을 감수해야만 하는 시대를 만났지만(정흉), 이런 때일수록 큰물을 건너는 모험을 감행해야 이로움이 있다(이섭대천)’는 뜻이 된다. “정흉은 객관적 판단이고 이섭대천은 주체적 결단이다.” 역경에 굴하지 않고 모험을 감행해야만 새로운 시대를 열 수 있다는 얘기다. 오늘의 우리를 향해 하는 말로 새겨도 좋을 것이다.

고명섭 선임기자 michael@hani.co.kr

Wang Bi (Wang Pi) | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Wang Bi (226—249 C.E.)

Wang Bi (Wang Pi), styled Fusi, is regarded as one of the most important interpreters of the classical Chinese texts known as the Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) and the Yijing (I Ching). He lived and worked during the period after the collapse of the Han dynasty in 220 C.E., an era in which elite interest began to shift away from Confucianism toward Daoism. As a self-identified Confucian, Wang Bi wanted to create an understanding of Daoism that was consistent with Confucianism but which did not fall into what he considered to be the errors of then-popular Daoist sectarian groups. He understood his main task to be the restoration of order and a sense of direction to Chinese society after the turbulent final years of the Han, and offered the ideal of establishing the “true way” (zhendao) as the solution. Although he died at the age of twenty-four, his interpretations of Daoism became influential for several reasons. The edition of the Daodejing that he used in his commentary on that work has been the basis for almost every translation into a Western language for nearly two centuries. Moreover, his interpretations of Daoist material did not undermine Confucianism, making them palatable to later Confucian thinkers. Finally, Wang Bi’s work provided a way of talking about indigenous Chinese beliefs that made them seem compatible with the introduction of Indian Buddhist texts and ideas in the decades to follow.

Table of Contents

- The Context of Wang Bi’s Work

- Wang Bi’s Commentaries

- Central Ideas in Wang Bi’s Writings

- Wang Bi’s Influence on Chinese Philosophy

- References and Further Reading

1. The Context of Wang Bi’s Work

Wang Bi lived and worked during the period after the collapse of the Han dynasty in 220 C.E., an era in which elite interest began to shift toward Daoism. A brief explanation of this transformation of intellectual interests in early medieval China is necessary in order to understand Wang Bi’s thought in its original context.

Beginning with the reign of Emperor Wu (c. 140-187 B.C.E.), the Han state embraced Confucianism as its official ideology. Training in the Confucian classics became mandatory for all officials, and there was an active program of suppression of alternative thought, including the persecution of Prince Liu An of Huainan, a prominent Daoist supporter. Nevertheless, Daoism did not disappear. By the first century C.E., Daoist texts began to reappear in political discussion, and during the following century, sectarian Daoist movements such as the tianshi (Celestial Masters) became active. Although Confucian scholars were still needed by the rulers of post-Han states such as the Wei because of their knowledge and experience in state rituals and administrative matters, by Wang Bi’s time Daoism was “in the air” and exercising a powerful influence on the thinking of commoner and aristocrat alike.

Accordingly, the interests of some members of the educated elite turned toward Daoism. They labored to create a renaissance in Daoist thought, but one that directly avoided following the religious beliefs and practices of the Celestial Masters and the various permutations of Daoism that had rapidly developed. These thinkers are generally gathered loosely under the title of xuanxue (Dark Learning, Mysterious Learning or Profound Learning), sometimes called Neo-Daoism. The term xuanxue was derived from a line in the first chapter of the Daodejing, according to which the dao (Way) is xuan zhi you xuan (darker than dark). Among the principal xuanxue figures were Zhong Hui (225-264 C.E.), Xiang Xiu (c. 223-300 C.E.), Guo Xiang (d. 312 C.E.), and Wang Bi.

A Confucian rather than a sectarian Daoist, Wang Bi wanted to create an understanding of Daoism that was consistent with Confucianism but which did not fall into what he considered to be the errors of the Celestial Masters and their popular religious practices. He understood his main task to be the restoration of order and a sense of direction to Chinese society after the turbulent final years of the Han. He offered the ideal of establishing the “true way” (zhendao) as the solution. Undoubtedly, his ultimate goal was to examine the mysterious knowledge of creation and translate it into a viable political and social program. Due to his untimely death, however, he had very little impact on the politics of his day. Nevertheless, through his commentarial work and the way in which his ideas were regarded as congenial to early Chinese Buddhism, his philosophical influence was profound.

2. Wang Bi’s Commentaries

Wang Bi’s best known commentaries are those on the Daodejing and Yijing. What is often overlooked is that he also wrote a commentary on the Confucian Analects (Lunyu Shiyi), some fragments of which still survive. His writings have been collected and annotated in two volumes entitled Wang Bi ji jiaoshi (Critical Edition of Wang Bi’s Collected Works). The bibliography below lists this work and other English translations of his major commentaries (see References and Further Reading).

a. On the Analects

What we know about the Analects commentary is that it was written as a criticism of the texts that Wang’s mentor He Yan (Ho Yen, d. 249 B.C.E.) considered to be most important. Wang’s approach, as far as we can tell from what remains of the commentary, was to focus on those passages that stress the limited capacity of language, especially with respect to the inability to define in language the nature of the sage. His selection of passages and remarks sets up a substantial rapprochement between Confucianism and his version of Daoism by basically providing him with a kind of hermeneutical license. His commentaries are in the zhangju (“chapter and verse”) format, in which a great deal of emphasis is placed on individual words and images in the “verses” and the meaning that lies behind them, carefully avoiding any sort of approach that regards philosophical concepts as referential.

b. On the Yijing

Wang’s commentary on the Yijing, a traditional Chinese divinatory text of uncertain antiquity consisting of hexagrams and their interpretations, cross-annotates it with the Daodejing. In this way, he transforms the interpretive tradition concerned with the Yijing by setting aside what he regards as an over-reliance on mathematical and symbolic readings of the text (typical of Han scholars) and exposing what he takes to be its xuanxue.For example, while Han thinkers such as Ma Rong (79-106 C.E.) tried to make textual images referential, Wang avoided this consistently. Alan Chan specifically mentions Ma’s explanation of the Yi jing comment, “the number of the great expansion is fifty, but use is made only of forty-nine.” Ma claims that “fifty” refers to the polestar, the two forms of yin and yang, the sun and moon, the four seasons, the five elements (wuxing), the twelve months, and the twenty-four calendar periods. In Ma’s interpretation, because the polestar does not move, it is not used, and thus the number is forty-nine, not fifty. In contrast to this approach, Wang looks behind the language for underlying principles or xuanxue meanings.

Wang’s commentary on the hexagrams draws heavily from passages in the Daodejing and Zhuangzi . He uses major Daoist ideas to interpret the Yijing, culminating in his theory that change and dao are unified and his position that Laozi’s ideas are already contained in the Yijing. He appropriates the notions of being (you) and nothingness (wu) from the Daodejing and uses them in his interpretation of divination.

c. On the Daodejing

Many of Wang’s most basic ideas concerning the Daodejing are discussed below. But with respect to his commentary on this work, he is probably as well known for the text that was transmitted with the commentary as he is famed for the commentary itself. This text became the basis, first for Chinese scholarship on the Daodejing, and later for translations of the text into Western languages. In his A Chinese Reading of the Daodejing: Wang Bi’s Commentary on the Laozi with Critical Text and Translation, the best-known Western scholar of Wang Bi, Rudolf Wagner, provides a careful study of Wang’s work on the text.

The recent translation of the Daodejing by Roger Ames and David Hall is based on a conflation of the two Mawangdui (MWD) versions of the text, supplemented by that of Wang Bi. Mawangdui is the name of a site near Changsha in Hunan province in which some early Han tombs containing texts were discovered in 1972. These discoveries include two incomplete editions of the Daodejing on silk scrolls, now simply called “A”and “B.” Ames and Hall believe that Wang was actually working from a textual source that was closer to their own conflated version of the MWD materials than the received text that he had put in his own commentary (Ames and Hall, 76). In contrast, another recent translator of the Daodejing, P.J. Ivanhoe, believes that although the MWD versions offer help with how one might translate certain passages, there is nothing in them that fundamentally conflicts with or alters our understanding of the core philosophical notions of the Wang Bi text.

Wang’s version of the Daodejing contains eighty-one chapters that are divided into two books, but the actual division of the text into two books predates the Wang Bi edition. Later versions of the text built upon that of Wang and added book and chapter titles. In Wang’s edition, Book One consists of chapters 1 through 37, and later it came to be called the dao half of the text. Book Two consists of chapters 38 to 81 and is known as the de half. One of the principal differences between the MWD versions and that of Wang Bi is that the order of the chapters is reversed, with 38-81 in the Wang Bi coming before chapters 1-37 in the MWD versions. Robert Henricks has published a translation of these texts with extensive notes and comparisons with the Wang Bi under the title Lao-Tzu: Te-tao Ching.

3. Central Ideas in Wang Bi’s Writings

a. On Language

A substantial part of Wang’s interpretive philosophy is rooted in his view of language. His view of language is consistent with that of the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi. Both works teach that words are inadequate for the expression of truth. As Daodejing 1 says, “The way that can be spoken of is not the constant way. The name that can be named is not the true name.” For Wang, this means that the dao lies beyond language He goes further, however, holding that words must always be distinguished from their underlying meaning. Indeed, Wang claims that taking words referentially is an obstacle to xuanxue — that words must be forgotten in order to penetrate into the world of meaning. He finds support for this view in classical Daoist texts. Specifically, he makes use of the Zhuangzi’s teaching about “forgetfulness” (chs. 4, 12, 24). This view of language gives Wang the freedom to uncover what he believes to be the profound meaning that lies behind the words of the classical texts of Daoism, which in turn makes it easier for him to tie them to the Yijing and even to the Confucius of the Analects. It also allows him to offer a construction of Daoist ideas that can be distinguished sharply from that of the sectarian Daoism of his day.

b. On Non-Being

Wang’s commentary on the Daodejing centers around his interpretation of the concept of “nothing” (wu) or “non-being” as that out of which the ten thousand things (e.g., all phenomena) arise. He believes that “nothing” is pointed to in the text by means of its fundamental analogies: valley, canyon, bowl, door, window, pitcher, and hub of a wheel. There can be no doubt that Wang regards “nothing” as the dao. When he explains the first sentence of Daodejing 6 (“The spirit of the valley never dies; it is called the obscure female”), he says, “The spirit of the valley is the Non-Being found in the center of a valley. The Non-Being has neither form, nor shadow; it conforms completely to what surrounds it….Its form is invisible: it is the Supreme Being.”

c. On “The One”

In articulating his understanding of the dao, Wang appeals directly to the Daodejing’s comments on cosmogony, according to which the dao gives birth to One, One gives birth to two, two to three, and three to the ten thousand things. Yet Wang does not believe that the One is a being. On the contrary, it is the mysterious center of things, like the hub of a wheel. The dao is Non-Being. Dao is not an agent. It does not have a will. To say that it lies at the “beginning” is not to make a temporal statement, but a metaphysical one. On Daodejing 25, Wang writes, “It is spoken of as ‘Dao’ insofar as there is thus something [for things] to come from.” Interpreting the fifty-first chapter, he writes, “The Dao—this is where things come from.” Wang makes his views clearer when he offers a commentary on the word “One.” Han thinkers took the One referentially and identified it with the North Star. But Wang takes a radically different approach. For him, the One is not used referentially in terms of some external thing, nor is it a number. It is that on which numbers depend.

The idea that the One underlies and unites all phenomena is also vigorously stressed in Wang’s commentary on the Yijing. In this work, Wang makes it clear just how it is that dao as Non-Being is related to the world of Being. The Yijing consists of hexagrams made up of six broken lines (representing the yin cosmic force) and unbroken lines (representing the yang cosmic force). Since ancient times, the text has been used as a tool for divination. In Wang’s day, the typical interpretation of a hexagram associated it with a specific external event, but Wang uses his theory of language to put forward the view that the hexagram’s meaning lies in identifying the general principle (li) behind all particular objects. Wang thinks that the principle is discoverable in one of the six lines of a hexagram, so that the other five become secondary. These principles constitute the fiber of the One.

d. On Wuwei

Wang Bi’s views on the sage reveal his understanding of wuwei (effortless action). He believes that the sage rises above all distinctions and contradictions. According to Wang, although the sage remains in the midst of human affairs, he accomplishes things by taking no unnatural action. Thus, the sage’s conduct is an example of wuwei. Wang is clear that this does not mean that the sage “folds his arms and sits in silence in the midst of some mountain forest.” It means that the sage acts naturally. To such a sage, all life transformations are the same and one must not impose value judgments on them. In making decisions, the sage should have “no deliberate mind of his own” (wuxin) but instead should respond to life events spontaneously, without any discrimination. In short, this means that the sage puts aside desires because they are corrupting and destructive. Strictly speaking, the sage’s wuwei is not a strategy to diminish desire; it is evidence of the absence of desire — emptiness, or Non-Being. In Wang’s view, Confucius was such a sage because his life had broadened the dao. (Analects 15.29) Such interpretations created fertile ground in which Buddhism could take root, thereby entering the Chinese intellectual stream through Daoism.

e. On Ziran

The Daoist concept of ziran (usually translated as “spontaneity” or “naturalness”) is interpreted by Wang Bi to mean “the real.” Likewise, in his commentary on the Daodejing, de is not a reference to virtue (as it usually is understood), or even less to specific virtues, but to that which persons obtain from dao (see ch. 51). Yet, for Wang, the text teaches that dao moves spontaneously and accomplishes its tasks. Providing for all, “nothing is done, but no thing is left undone.” Thus, Wang thinks that humans have created disorder by their thought and action. If they return to dao in wuwei, then de will become available as ziran. De will not be the result of human action, politics, or contrivance. If the ruler becomes a sage and embraces wuwei, he will transform the people and broaden the dao, just as Confucius (not Laozi) did.

4. Wang Bi’s Influence on Chinese Philosophy

Wang Bi’s metaphysics has influenced the development of Chinese philosophy in at least two important respects.

First, after Wang Bi, some Chinese literati began to distinguish “philosophical” Daoism (daojia) from “religious” Daoism (daojiao), a distinction that was reinforced by the geographical relocation of the tianshi movement and elite attempts to devalue it as a legitimate extension of classical Daoist thought. This distinction has persisted throughout the history of Chinese thought, but it is an unfortunate one, and moreover one without any basis in the historical practice of Daoist communities (Kirkland, 2). In constructing his interpretive framework, Wang avoided sectarian Daoism and did not take seriously the philosophical roots of tianshi thought. He made no serious attempt to consider how Daoism was practiced before the Han. Thus, Wang’s typology of Daoism laid the groundwork for what is arguably not only the most influential, but also the most systematically misleading, way of thinking about the development of Chinese philosophy.

Second, Wang’s commentary on the Daodejing was crucial for the process by which the Mahayana Buddhist dharma (doctrine, teaching) began to gain a foothold in China. The most obvious example of Wang’s influence can be seen in the way the Mahayana notion of emptiness was assimilated into Chinese thought. According to Wang, the Daodejing (ch. 40) asserts that being comes from nonbeing, and that nonbeing is the ultimate substance of being. As we have seen, he exploited the Daodejing’s analogies for emptiness, reading their meaning in terms of xuanxue. As Buddhist texts such as the Prajnaparamita (Transcendental Wisdom) Sutra were translated, clear connections were made between its teaching that all forms are empty and Wang’s reading of the dao. So, it became widely believed, or at least widely proclaimed, by early Chinese Buddhists that Laozi and Buddha had both taught the need for a return to non-being. Wang’s commentarial work played a strategic role in making this interpretation more convincing.

5. References and Further Reading

- Ames, Roger and David L. Hall, trans. Daodejing — Making This Life Significant: A Philosophical Translation. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003.

- Chan, Alan. Two Visions of the Way: A Study of the Wang Pi and Ho-shang Kung Commentaries on the Lao-tzu. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1991.

- Chang, Chung-yue. “Wang Pi on the Mind.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 9 (1982): 77-106.

- Henricks, Robert, trans. Lao-Tzu: Te-Tao Ching. New York: Ballantine, 1989.

- Ivanhoe, P.J., trans. The Daodejing of Laozi. New York: Seven Bridges, 2002.

- Kirkland, Russell. “Understanding Taoism.” In Kirkland, Taoism: The Enduring Tradition (New York and London: Routledge, 2004), 1-19.

- Kohn, Livia. Early Chinese Mysticism: Philosophy and Soteriology in the Taoist Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Lin, Paul, trans. A Translation of Lao-tzu’s Tao-te-ching and Wang Pi’s Commentary. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1977.

- Lou, Yu lie. Wang Bi ji jiaoshi (Critical Edition of Wang Bi’s Collected Works). 2 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1980.

- Lynn, Richard, trans. The Classic of Changes: A New Translation of the as Interpreted by Wang Bi. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

- Lynn, Richard, trans. The Classic of the Way and Virtue; A New Translation of the Tao-te Ching of Laozi as Interpreted by Wang Bi. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- Rump, Arian and Wing-tsit Chan, trans. Commentary on the Lao-tzu by Wang Pi. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1979. .

- Wagner, Rudolf. The Craft of the Chinese Commentator: Wang Bi on the Laozi. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2000.

- Wagner, Rudolf, trans. A Chinese Reading of the Daodejing: Wang Bi’s Commentary on the Laozi with Critical Text and Translation. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2003.

- Wagner, Rudolf. Language, Ontology, and Political Philosophy in China: Wang Bi’s Scholarly Exploration of the Dark (Xuanxue). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2003.

Author Information

Ronnie Littlejohn

Email: ronnie.littlejohn@belmont.edu

Belmont University

U. S. A.

왕비 王弼- Wikipedia, 중국어 백과사전

왕비 [ 편집 ]

| 왕비 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 국가 | 차오 웨이 | ||

| 연대 | 삼국지 | ||

| 주님 | 카오팡 | ||

| 성 | 왕 | ||

| 이름 | 뷰트 | ||

| 성격 | 자회사 | ||

| 공식적인 | 따랑 | ||

| 고향 | 산양군 | ||

| 태어난 | 황초 7년(226년) | ||

| 돌아가다 | 정시 10년(249년) | ||

| |||

| 책 | |||

| " 노자 의 도덕경에 대한 메모 " , " 노자 에 대한 안내 ", " 주 이에 대한 메모 ", " 주이 ", " 공자의 논어 " ? | |||

왕비 (226-249), 호칭 푸시 (密密) 는 산양현 (지금의 산동성 ) 출신이다. 삼국 시대 동안 , 조 위 의 유명한 서기 , 이 학자 , 그리고 위 와 금 형이상학 의 주요 대표자 중 하나 .

그의 아버지는 Wang Ye 입니다. 왕홍 형제 . 그의 할아버지 Wang Kai 는 Wang Can 의 형이었고 그의 할머니는 Liu Biao 의 딸이었습니다. (" 박물관 ")

그는 후대에 큰 영향을 미친 도덕경 과 변경 에 대한 주석 을 썼습니다. 한나라와 삼국의 "도덕경" 주석판이 대부분 소실된 이후로 왕비의 " 도덕경 주석 "이 이 책의 가장 초기 주석판이 되었다.

인생 [ 편집 ]

그는 젊었을 때 매우 똑똑했고 10살이 넘었을 때 좋은 노인 이었고 그의 말솜씨가 뛰어났으며 그는 Zhonghui만큼 유명했습니다. 약하지 않았을 때는 이미 당시 관료와 문인들이 알고 있었다. 비회 는 관리 대신 인 비회 를 만나 이상하게 여겨 물었다. 왕비는 “성인에게는 몸이 없고 몸이 없으면 가르칠 수 없으므로 나는 그것에 대해 말하지 않는다. 노자는 할 말이 있다”고 대답했다. (" 왕비 전기 ". " Shishuo Xinyu , 문학 " 기록에 따르면 Pei Hui는 약한 왕관 이후에 나타났으며 Hui는 "남편은 아무도없고 모든 것의 자원이 성실하며 성인 Moken은 말합니다. 노자심자(老子神志 . 나중에 Fu Yan 에게도 알려졌습니다 . 당시 하연 은 관료 였고 왕비의 재능에 크게 놀랐다. 정석 시대에 황문 을 섬기는 사람이 없었고, 하연 은 이미 가총 , 비수 , 주정 을 임명하고 왕비의 임명을 논의했다. 딩미 _하연과 경쟁하여 조솽 에게 고이 의 왕리 를 추천 합니다. 그래서 조솽 은 왕리를 임명하고 왕비를 대신하여 태랑으로 임명 하였다. 즉위 후 조솽을 만났고 조솽은 물러났고 왕비는 그와 대화만 하였으므로 조솽에게 멸시를 받았다. 그 당시 조솽은 독재정권이었고 측근을 임명했다. Wang Bi는 지식이 풍부하고 평판을 관리하지 않습니다. 왕리가 병으로 죽고 조쌍이 왕리를 왕심으로 대치 하고 왕비가 그의 종파에 들어갈 수 없게 되자 하연은 한숨을 쉬었다. 너무 어린 나이에 공직에 소질이 없었기 때문에 주목받지 못했다.

화이난 태생 인 류타 오는 수직과 수평을 잘 말하며 당시 사람들의 추천을 받아 왕비와 이야기할 때마다 왕비에게 설득당하는 경우가 많았다.

하연은 성자에게 기쁨, 노여움, 슬픔, 기쁨이 없다고 생각하고 그의 주장은 매우 교묘하고 중회(Zhong Hui)와 다른 사람들도 동의합니다. 반면 왕비는 성인이 인간보다 신이 더 많고 오감이 인간과 같다고 믿고 있으며, 또한 사물에 부담을 느끼지 않고 사물에 반응하는 사람이다. , 더 이상 물건에 반응을 하지 않고, 많은 것을 잃었다고 한다."

" 변화 의 책 " 에 주석 을 달고 난 후, Yingchuan 출신 인 Xun Rong 은 Wang Bi에게 "Xu Ci Shang "에서 "Dayan"의 의미를 물었습니다. Wang Bi는 Xun Rong의 의미에 답하고 Xun Rong에게 아이러니하게 편지 를 썼습니다 . 만나면 기쁨이 없고, 길을 잃으면 슬픔이 없을 수 없다. 또한 아피스 사람들은 흔히 감성으로 이성을 따라갈 수 없다고 생각하지만, 이제는 자연이 무자비하다는 것을 안다. 마음에 새기고 열흘이 지나니 애증이 너무 많아 아버지가 연자에게는 큰 차이가 없다."

정석 10년 (249) 조상이 폐위되고 왕비도 해임되었다. 같은 해 가을, 그는 24세의 나이로 질병으로 사망했습니다.

사람들, 일화 [ 편집 ]

- 잔치 를 좋아하는 성격 과 명성 도 냄비 던지기 를 잘 하는 리듬 을 알고 있습니다. 그러나 왕비는 자신의 재능으로 남을 비웃는 일이 많았고, 당시 학자들의 미움을 받았다. (" 왕비의 전기 ")

- 시계 와 친해지기. Zhong Hui의 논의는 주로 학교 교육에 관한 것이지만 Wang Bi의 정교함에 감탄하기도 했습니다. ("왕비의 전기")

- 처음에는 Wang Li 및 Xun Rong 과 친했습니다 . 후에 왕리는 황문 (黃門)의 신하로 임명되자 왕리 를 원망했다. 그리고 Xun Rong도 사이가 나빠졌습니다. ("왕비의 전기")

- 내가 약하지 않을 때 , 나는 He Yan 을 만나러 갔고 , 그 때 테이블이 가득 찼습니다. 허연은 왕비의 이름을 듣고 승자의 논리로 왕비에게 "이 원리는 대단히 좋은데 다시 얻기 어렵다"고 물었고, 왕비는 질문을 했고, 청중은 모두 확신했다. Wang Bi는 호스트이자 게스트로서 여러 번 자신에게 질문했으며 그의 의견은 군중의 손이 닿지 않는 범위에 있었습니다. (" Shi Shuo Xin Yu , 문학 ")

- 하연은 한때 ' 노자 '를 주해했지만 완성되지 않았다. 왕비의 노자 칙령 주석에 대한 자신의 논평을 보고 왕비의 주석이 정교하기 때문에 자기가 열등하다고 생각하여 대응할 수 없었다 . " ("시 슈오 Xin Yu, 문학")

- 그가 죽은 후 사마시 와 다른 통찰력 있는 사람들도 그를 보고 한숨을 쉬었습니다. ("왕비의 전기")

- 느와르는 '변경'에 주석을 달았을 때 '정현'을 유교자로 비웃으며 ' 노인은 아무 의도가 없었다'고 생각했다고 한다. 한밤중에 갑자기 외부 정자에서 발자국 소리가 들리고 누군가가 와서 자신을 Zheng Xuan이라고 부르며 "당신은 젊습니다. 당신은 왜 노자처럼 가볍게 쓰고 비방합니까?" 왼쪽. 왕비는 악을 두려워하여 곧 중병으로 사망했습니다. (" 유 밍 루 , 볼륨 3 ")

평가 [ 편집 ]

- 허연 은 한숨을 쉬며 " 중니 가 말하길 미래의 삶은 무섭고, 인간이라면 하늘이나 인간에 비견될 수 있다"고 말했다. (" 왕비의 전기 ", " 시슈오신위 , 문학 ")

- Wang Ji는 말하기를 좋아하고 병들고 늙고 , Zhuang 은 종종 "Bi Yi가 언급한 것을 보고 이해한 사람들이 많이 있습니다." ("왕비의 전기")

- He Shao : "Bi의 재능은 탁월하고 그가 얻은 것을 얻으면 그것을 빼앗을 수 없습니다." 옌비는 천박하고 아무것도 모르는 사람이다", "도복희의 관용구를 말할 때 그는 별로 얀이 아닌, 자연스럽게 칭찬을 많이 받는다"고 말했다. ("왕비의 전기")

- Chen Shou : "Bi는 유교와 도교 에 대해 이야기하는 것을 좋아하고 유교 에 대해서만 이야기할 수 있습니다." (" 삼국지 , Zhong Hui 전기 ")

- Sun Sheng 은 " 변경의 책 은 지식과 지식이 부족한 책이며 세계에서 최고가 아닙니다. 그것을 어떻게 비교할 수 있습니까? 세계의 논평은 거의 모두 거짓입니다. 조건 Bi는 Fu Hui의 구별을 사용하고 현현을 일반화하고자 한다.목적이 무엇인가?그러므로 그 웅변적 의미가 눈에 넘치고 음양이 들리지 않을 것이다.육행의 변화, 이미지군 효과, 요일, 시간, 년, 5상, 시신이 다 엎어지고, 무의미한 일도 많다. 지켜보는 사람은 있어도 길이 진흙탕이 될까 두렵다"고 말했다. (" 삼국지 , 중회전기")

- 동진(東晉) 의 패닝( Fanning ) : "황당과 묘는 도교까지 이르고 호포는 노래를 멈추고 대중적이고 대중적이며 인과 의의 표징을 위해 경쟁하며 옳고 그름은 유교 . 핑 삼촌 의 정신은 초월적이고 그의 상속자들은 영리하고 미묘하며 수천 년 동안 영감을 얻었습니다. 퇴폐적인 지침은 Zhou Kong의 먼지 그물에 떨어집니다. Haoliang의 장인 Sigaixunmian의 용문 . 스승님의 설을 들어보니 제와 주에 대한 죄라고 생각한다 . 그게 뭔데?" 생일을 자랑스럽게 생각하는 치의 매력을 그리는 것은 우연의 일치이고, 부채는 관례로 검열되지 않는다. 정승의 혼돈과 나라의 전복은 사실이다. 나는 일생의 재앙은 가벼우며, 과거 왕조의 범죄는 무겁고, 애도의 도발은 작으며, 팬들은 길을 잃는다고 굳게 믿는다. 군중의 죄가 크다.” (" 진의 서 , 패닝의 전기 ")

- 북과 남조 의 Liu Xie : "위나라 초기에 그는 예술과 방법 모두의 대가였습니다 . Fu Yan 과 Wang Can 은 이름 이론 을 연구 하고 실천 했습니다 . 태초 까지 그는 원했습니다 . 텍스트를 따르기 위해; He Yan의 제자가 번영하기 시작했습니다 . 투쟁 이 끝났습니다. Lan Shi 의 "Talent", Zhong Xuan 의 "Going to Cut", Shu Ye 의 "Discrimination of Voices", Tai Chu 를 보십시오. 의 "Original No", Fu Hei의 "Two Cases", Shu Ping의 두 번째 이론, 그리고 선생님의 마음은 독특하고 날카롭고 정확하며 영어도 가득하다. 본문의 본문은 비록 잡다한 기사가 다를지라도 항상 같을 것입니다. 진연군 주석 " 요전 " 이 100,000단어 이상 이라면 Zhu Wengong 의 " Shangshu " 해석 은 300,000 단어 이므로 챕터 를 배우는 것이 귀찮고 창피합니다 . " 이"를 해석하십시오. 제안이 명확하고 매끄럽고 공식으로 수행 할 수 있습니다." ("Wenxin은 용 을 조각했습니다. 토론 ")

- 수나라 연지 의는 "현종의 조상인 하연과 왕비는 서로를 칭찬하고 풀밭에 붙어 있는 풍경을 칭찬했다. 사람을 웃게 하고 병에 걸리고 존재의 함정에 빠지는 것은 너무 많다. 적극적인." (" Yan's Family Instruction , Mian Xue ")

- 당(唐)나라 공영다(公英多) : "고대와 근세에 위나라 왕과 후계자의 관심은 단 하나뿐이다." (" 쉬운 정의 서문 ")

- 송나라 주희 : "왕비주이, 영리하지만 명료하지 않다". (" Zhuzi Language Classes , Mencius One ")

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

- Tang Yongtong : "고귀한 철학의 학습 - Wang Bi ( 페이지 아카이브 및 백업 , 인터넷 아카이브 에 저장됨 )".

- Jin Guzhi : ""무"에 대한 생각의 확장 - 노자에서 왕비까지 ( 페이지 아카이브 및 백업 , 인터넷 아카이브 에 저장됨 )".

- Tianhuo Yijing 리소스 네트워크 Wang Bi Zhou Yi 참고 쿼리 ( 페이지 아카이브 백업 , 인터넷 아카이브 에 저장 )

관련 기사 [ 편집 ]

| Wikisource 의 관련 원본 문헌 : Wang Bi |

| Wikiquote 에서 Wang Bi 의 인용문 |