Terence McKenna

Terence McKenna | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 16, 1946 Paonia, Colorado, U.S. |

| Died | April 3, 2000 (aged 53) San Rafael, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Author, lecturer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | BSc in ecology, resource conservation, and shamanism |

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley |

| Period | 20th |

| Subject | Shamanism, ethnobotany, ethnomycology, metaphysics, psychedelic drugs, alchemy |

| Notable works | The Archaic Revival, Food of the Gods, The Invisible Landscape, Psilocybin Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide, True Hallucinations. |

| Spouse | Kathleen Harrison (1975–1992; divorced) |

| Children | Finn McKenna & Klea McKenna |

| Relatives | Dennis McKenna (brother) |

Terence Kemp McKenna (November 16, 1946 – April 3, 2000) was an American ethnobotanist and mystic who advocated the responsible use of naturally occurring psychedelic plants. He spoke and wrote about a variety of subjects, including psychedelic drugs, plant-based entheogens, shamanism, metaphysics, alchemy, language, philosophy, culture, technology, environmentalism, and the theoretical origins of human consciousness. He was called the "Timothy Leary of the '90s",[1][2] "one of the leading authorities on the ontological foundations of shamanism",[3] and the "intellectual voice of rave culture".[4]

McKenna formulated a concept about the nature of time based on fractal patterns he claimed to have discovered in the I Ching, which he called novelty theory,[3][5] proposing that this predicted the end of time, and a transition of consciousness in the year 2012.[5][6][7][8] His promotion of novelty theory and its connection to the Maya calendar is credited as one of the factors leading to the widespread beliefs about 2012 eschatology.[9] Novelty theory is considered pseudoscience.[10][11]

Biography

Early life

Terence McKenna was born and raised in Paonia, Colorado,[5][12][13][unreliable source?] with Irish ancestry on his father's side of the family.[14]

McKenna developed a hobby of fossil-hunting in his youth and from this he acquired a deep scientific appreciation of nature.[15] He also became interested in psychology at a young age, reading Carl Jung's book Psychology and Alchemy at the age of 14.[6] This was the same age McKenna first became aware of magic mushrooms, when reading an essay titled "Seeking the Magic Mushroom" which appeared in the May 13, 1957 edition of LIFE magazine.[16]

At age 16 McKenna moved to Los Altos, California to live with family friends for a year. He finished high school in Lancaster, California.[13] In 1963, he was introduced to the literary world of psychedelics through The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell by Aldous Huxley and certain issues of The Village Voice which published articles on psychedelics.[3][13]

McKenna said that one of his early psychedelic experiences with morning glory seeds showed him "that there was something there worth pursuing",[13] and in interviews he claimed to have smoked cannabis daily since his teens.[17]

Studying and traveling

In 1965, McKenna enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley and was accepted into the Tussman Experimental College.[17] While in college in 1967 he began studying shamanism through the study of Tibetan folk religion.[3][18] That same year, which he called his "opium and kabbala phase",[6][19] he traveled to Jerusalem where he met Kathleen Harrison, an ethnobotanist who later became his wife.[6][17][19]

In 1969, McKenna traveled to Nepal led by his interest in Tibetan painting and hallucinogenic shamanism.[20] He sought out shamans of the Tibetan Bon tradition, trying to learn more about the shamanic use of visionary plants.[12] During his time there, he also studied the Tibetan language[20] and worked as a hashish smuggler,[6] until "one of his Bombay-to-Aspen shipments fell into the hands of U. S. Customs."[21] He then wandered through southeast Asia viewing ruins,[21] and spent time as a professional butterfly collector in Indonesia.[6][22][23]

After his mother's death[24] from cancer in 1970,[25] McKenna, his brother Dennis, and three friends traveled to the Colombian Amazon in search of oo-koo-hé, a plant preparation containing dimethyltryptamine (DMT).[5][24][26] Instead of oo-koo-hé they found fields full of gigantic Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms, which became the new focus of the expedition.[5][6][12][24][27] In La Chorrera, at the urging of his brother, McKenna was the subject of a psychedelic experiment[5] in which the brothers attempted to bond harmine (harmine is another psychedelic compound they used synergistically with the mushrooms) with their own neural DNA, through the use of a set specific vocal techniques. They hypothesised this would give them access to the collective memory of the human species, and would manifest the alchemists' Philosopher's Stone which they viewed as a "hyperdimensional union of spirit and matter".[28] McKenna claimed the experiment put him in contact with "Logos": an informative, divine voice he believed was universal to visionary religious experience.[29] McKenna also often referred to the voice as "the mushroom", and "the teaching voice" amongst other names.[16] The voice's reputed revelations and his brother's simultaneous peculiar psychedelic experience prompted him to explore the structure of an early form of the I Ching, which led to his "Novelty Theory".[5][8] During their stay in the Amazon, McKenna also became romantically involved with his interpreter, Ev.[30]

In 1972, McKenna returned to U.C. Berkeley to finish his studies[17] and in 1975, he graduated with a degree in ecology, shamanism, and conservation of natural resources.[3][22][23] In the autumn of 1975, after parting with his girlfriend Ev earlier in the year,[31] McKenna began a relationship with his future wife and the mother of his two children, Kathleen Harrison.[8][17][19][26]

Soon after graduating, McKenna and Dennis published a book inspired by their Amazon experiences, The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens and the I Ching.[5][17][32] The brothers' experiences in the Amazon were the main focus of McKenna's book True Hallucinations, published in 1993.[12] McKenna also began lecturing[17] locally around Berkeley and started appearing on some underground radio stations.[6]

Psilocybin mushroom cultivation

McKenna, along with his brother Dennis, developed a technique for cultivating psilocybin mushrooms using spores they brought to America from the Amazon.[16][26][27][31] In 1976, the brothers published what they had learned in the book Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide, under the pseudonyms "O.T. Oss" and "O.N. Oeric".[12][33] McKenna and his brother were the first to come up with a reliable method for cultivating psilocybin mushrooms at home.[12][17][26][27] As ethnobiologist Jonathan Ott explains, "[the] authors adapted San Antonio's technique (for producing edible mushrooms by casing mycelial cultures on a rye grain substrate; San Antonio 1971) to the production of Psilocybe [Stropharia] cubensis. The new technique involved the use of ordinary kitchen implements, and for the first time the layperson was able to produce a potent entheogen in his [or her] own home, without access to sophisticated technology, equipment, or chemical supplies."[34] When the 1986 revised edition was published, the Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide had sold over 100,000 copies.[12][33][35]

Mid- to later life

Public speaking

In the early 1980s, McKenna began to speak publicly on the topic of psychedelic drugs, becoming one of the pioneers of the psychedelic movement.[36] His main focus was on the plant-based psychedelics such as psilocybin mushrooms (which were the catalyst for his career),[12] ayahuasca, cannabis, and the plant derivative DMT.[6] He conducted lecture tours and workshops[6] promoting natural psychedelics as a way to explore universal mysteries, stimulate the imagination, and re-establish a harmonious relationship with nature.[37] Though associated with the New Age and Human Potential Movements, McKenna himself had little patience for New Age sensibilities.[3][7][8][38] He repeatedly stressed the importance and primacy of the "felt presence of direct experience", as opposed to dogma.[39]

In addition to psychedelic drugs, McKenna spoke on a wide array of subjects,[26] including shamanism; metaphysics; alchemy; language; culture; self-empowerment; environmentalism, techno-paganism; artificial intelligence; evolution; extraterrestrials; science and scientism; the Web; virtual reality (which he saw as a way to artistically communicate the experience of psychedelics); and aesthetic theory, specifically about art/visual experience as information representing the significance of hallucinatory visions experienced under the influence of psychedelics.[citation needed]

McKenna soon became a fixture of popular counterculture[5][6][37] with Timothy Leary once introducing him as "one of the five or six most important people on the planet"[41] and with comedian Bill Hicks' referencing him in his stand-up act[42] and building an entire routine around his ideas.[26] McKenna also became a popular personality in the psychedelic rave/dance scene of the early 1990s,[22][43] with frequent spoken word performances at raves and contributions to psychedelic and goa trance albums by The Shamen,[7][26][37] Spacetime Continuum, Alien Project, Capsula, Entheogenic, Zuvuya, Shpongle, and Shakti Twins. In 1994 he appeared as a speaker at the Starwood Festival, documented in the book Tripping by Charles Hayes.[44]

McKenna published several books in the early-to-mid-1990s including: The Archaic Revival; Food of the Gods; and True Hallucinations.[6][12][22] Hundreds of hours of McKenna's public lectures were recorded either professionally or bootlegged and have been produced on cassette tape, CD and MP3.[26] Segments of his talks have gone on to be sampled by many musicians and DJ's.[4][26]

McKenna was a colleague and close friend of chaos mathematician Ralph Abraham, and author and biologist Rupert Sheldrake. He conducted several public and many private debates with them from 1982 until his death.[45][46][47] These debates were known as trialogues and some of the discussions were later published in the books: Trialogues at the Edge of the West and The Evolutionary Mind.[3][45]

Botanical Dimensions

In 1985, McKenna founded Botanical Dimensions with his then-wife, Kathleen Harrison.[22][48] Botanical Dimensions is a nonprofit ethnobotanical preserve on the Big Island of Hawaii,[3] established to collect, protect, propagate, and understand plants of ethno-medical significance and their lore, and appreciate, study, and educate others about plants and mushrooms felt to be significant to cultural integrity and spiritual well-being.[49] The 19-acre (7.7 ha) botanical garden[3] is a repository containing thousands of plants that have been used by indigenous people of the tropical regions, and includes a database of information related to their purported healing properties.[50] McKenna was involved until 1992, when he retired from the project,[48] following his and Kathleen's divorce earlier in the year.[17] Kathleen still manages Botanical Dimensions as its president and projects director.[49]

After their divorce, McKenna moved to Hawaii permanently, where he built a modernist house[17] and created a gene bank of rare plants near his home.[22] Previously, he had split his time between Hawaii and Occidental, CA.

Death

McKenna was a longtime sufferer of migraines, but on 22 May 1999 he began to have unusually extreme and painful headaches. He then collapsed due to a brain seizure.[27] McKenna was diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, a highly aggressive form of brain cancer.[7][12][27] For the next several months he underwent various treatments, including experimental gamma knife radiation treatment. According to Wired magazine, McKenna was worried that his tumor may have been caused by his psychedelic drug use, or his 35 years of daily cannabis smoking; however, his doctors assured him there was no causal relation.[27]

In late 1999, McKenna described his thoughts concerning his impending death to interviewer Erik Davis:

McKenna died on April 3, 2000, at the age of 53.[7][8][17]

Library fire and insect collection

On February 7, 2007, McKenna's library of over 3000 rare books and personal notes was destroyed in a fire at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California. An index of McKenna's library was made by his brother Dennis.[52][53] His daughter, the artist and photographer Klea McKenna, subsequently preserved his insect collection, turning it into a gallery installation, and then publishing it in book form as The Butterfly Hunter, featuring her selected photos of 122 insects – 119 butterflies/moths and three beetles or beetle-like insects – from a set of over 2000 he collected between 1969 and 1972, as well as maps showing his collecting routes through the rainforests of Southeast Asia and South America.[54] McKenna had intensively studied Lepidoptera and entomology in the 1960s, and as part of his studies hunted for butterflies primarily in Colombia and Indonesia. McKenna's insect collection was consistent with his interest in Victorian-era explorers and naturalists, and his worldview based on close observation of nature. In the 1970s, when he was still collecting, he became quite squeamish and guilt-ridden about the necessity of killing butterflies in order to collect and classify them, and that's what led him to stop his entomological studies, according to his daughter.[54]

Thought

Psychedelics

Terence McKenna advocated the exploration of altered states of mind via the ingestion of naturally occurring psychedelic substances;[5][32][43] for example, and in particular, as facilitated by the ingestion of high doses of psychedelic mushrooms,[26][55] ayahuasca, and DMT,[6] which he believed was the apotheosis of the psychedelic experience. He was less enthralled with synthetic drugs,[6] stating, "I think drugs should come from the natural world and be use-tested by shamanically orientated cultures ... one cannot predict the long-term effects of a drug produced in a laboratory."[3]

McKenna always stressed the responsible use of psychedelic plants, saying:

He also recommended, and often spoke of taking, what he called "heroic doses",[32] which he defined as five grams of dried psilocybin mushrooms,[6][57] taken alone, on an empty stomach, in silent darkness, and with eyes closed.[26][27] He believed that when taken this way one could expect a profound visionary experience,[26] believing it is only when "slain" by the power of the mushroom that the message becomes clear.[55]

Although McKenna avoided giving his allegiance to any one interpretation (part of his rejection of monotheism), he was open to the idea of psychedelics as being "trans-dimensional travel". He proposed that DMT sent one to a "parallel dimension"[8] and that psychedelics literally enabled an individual to encounter "higher dimensional entities",[58] or what could be ancestors, or spirits of the Earth,[59] saying that if you can trust your own perceptions it appears that you are entering an "ecology of souls".[60] McKenna also put forward the idea that psychedelics were "doorways into the Gaian mind",[43][61] suggesting that "the planet has a kind of intelligence, it can actually open a channel of communication with an individual human being" and that the psychedelic plants were the facilitators of this communication.[62][63]

Machine elves

McKenna spoke of hallucinations while on DMT in which he claims to have met intelligent entities he described as "self-transforming machine elves".[3][8][64][65]

Psilocybin panspermia speculation

In a more radical version of biophysicist Francis Crick's hypothesis of directed panspermia, McKenna speculated on the idea that psilocybin mushrooms may be a species of high intelligence,[3] which may have arrived on this planet as spores migrating through space[8][66] and which are attempting to establish a symbiotic relationship with human beings. He postulated that "intelligence, not life, but intelligence may have come here [to Earth] in this spore-bearing life form". He said, "I think that theory will probably be vindicated. I think in a hundred years if people do biology they will think it quite silly that people once thought that spores could not be blown from one star system to another by cosmic radiation pressure," and also believed that "few people are in a position to judge its extraterrestrial potential, because few people in the orthodox sciences have ever experienced the full spectrum of psychedelic effects that are unleashed."[3][7][18]

Opposition to organized religion

McKenna was opposed to Christianity[67] and most forms of organized religion or guru-based forms of spiritual awakening, favouring shamanism, which he believed was the broadest spiritual paradigm available, stating that:

Technological singularity

During the final years of his life and career, McKenna became very engaged in the theoretical realm of technology. He was an early proponent of the technological singularity[8] and in his last recorded public talk, Psychedelics in the age of intelligent machines, he outlined ties between psychedelics, computation technology, and humans.[69] He also became enamored with the Internet, calling it "the birth of [the] global mind",[17] believing it to be a place where psychedelic culture could flourish.[27]

Admired writers

Either philosophically or religiously, he expressed admiration for Marshall McLuhan, Alfred North Whitehead, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Carl Jung, Plato, Gnostic Christianity, and Alchemy, while regarding the Greek philosopher Heraclitus as his favorite philosopher.[70]

McKenna also expressed admiration for the works of writers including Aldous Huxley,[3] James Joyce, whose book Finnegans Wake he called "the quintessential work of art, or at least work of literature of the 20th century,"[71] science fiction writer Philip K. Dick, who he described as an "incredible genius,"[72] fabulist Jorge Luis Borges, with whom McKenna shared the belief that "scattered through the ordinary world there are books and artifacts and perhaps people who are like doorways into impossible realms, of impossible and contradictory truth"[8] and Vladimir Nabokov; McKenna once said that he would have become a Nabokov lecturer if he had never encountered psychedelics.

"Stoned ape" theory of human evolution

McKenna's hypothesis concerning the influence of psilocybin mushrooms on human evolution is known as "the 'stoned ape' theory."[16][43][73]

In his 1992 book Food of the Gods, McKenna proposed that the transformation from humans' early ancestors Homo erectus to the species Homo sapiens mainly had to do with the addition of the mushroom Psilocybe cubensis in the diet,[26][73][74] an event that according to his theory took place in about 100,000 BCE (which is when he believed that the species diverged from the genus Homo).[22][75] McKenna based his theory on the main effects, or alleged effects, produced by the mushroom[3] while citing studies by Roland Fischer et al. from the late 1960s to early 1970s.[76][77]

McKenna stated that, due to the desertification of the African continent at that time, human forerunners were forced from the increasingly shrinking tropical canopy into search of new food sources.[6] He believed they would have been following large herds of wild cattle whose dung harbored the insects that, he proposed, were undoubtedly part of their new diet, and would have spotted and started eating Psilocybe cubensis, a dung-loving mushroom often found growing out of cowpats.[6][7][43][78]

McKenna's hypothesis was that low doses of psilocybin improve visual acuity, particularly edge detection, meaning that the presence of psilocybin in the diet of early pack hunting primates caused the individuals who were consuming psilocybin mushrooms to be better hunters than those who were not, resulting in an increased food supply and in turn a higher rate of reproductive success.[3][7][16][26][43] Then at slightly higher doses, he contended, the mushroom acts to sexually arouse, leading to a higher level of attention, more energy in the organism, and potential erection in the males,[3][7] rendering it even more evolutionarily beneficial, as it would result in more offspring.[26][43][74] At even higher doses, McKenna proposed that the mushroom would have acted to "dissolve boundaries," promoting community bonding and group sexual activities.[12][43] Consequently, there would be a mixing of genes, greater genetic diversity, and a communal sense of responsibility for the group offspring.[79] At these higher doses, McKenna also argued that psilocybin would be triggering activity in the "language-forming region of the brain", manifesting as music and visions,[3] thus catalyzing the emergence of language in early hominids by expanding "their arboreally evolved repertoire of troop signals."[7][26] He also pointed out that psilocybin would dissolve the ego and "religious concerns would be at the forefront of the tribe's consciousness, simply because of the power and strangeness of the experience itself."[43][79]

According to McKenna, access to and ingestion of mushrooms was an evolutionary advantage to humans' omnivorous hunter-gatherer ancestors,[26][78] also providing humanity's first religious impulse.[78][80] He believed that psilocybin mushrooms were the "evolutionary catalyst"[3] from which language, projective imagination, the arts, religion, philosophy, science, and all of human culture sprang.[7][8][27][78]

Criticism

McKenna's "stoned ape" theory has not received attention from the scientific community and has been criticized for a relative lack of citation to any of the paleoanthropological evidence informing our understanding of human origins. His ideas regarding psilocybin and visual acuity have been criticized as misrepresentations of Fischer et al.'s findings, who published studies about visual perception in terms of various specific parameters, not acuity. Criticism has also been expressed because, in a separate study on psilocybin-induced transformation of visual space, Fischer et al. stated that psilocybin "may not be conducive to the survival of the organism". There is also a lack of scientific evidence that psilocybin increases sexual arousal, and even if it does, it does not necessarily entail an evolutionary advantage.[81] Others have pointed to civilisations such as the Aztecs, who used psychedelic mushrooms (at least among the Priestly class), that didn't reflect McKenna's model of how psychedelic-using cultures would behave, for example, by carrying out human sacrifice.[12] There are also examples of Amazonian tribes such as the Jivaro and the Yanomami who use ayahuasca ceremoniously and who are known to engage in violent behaviour. This, it has been argued, indicates the use of psychedelic plants does not necessarily suppress the ego and create harmonious societies.[43]

Archaic revival

One of the main themes running through McKenna's work, and the title of his second book, was the idea that Western civilization was undergoing what he called an "archaic revival".[3][26][82]

His notion was that Western society has become "sick" and is undergoing a "healing process": In the same way that the human body begins to produce antibodies when it feels itself to be sick, humanity as a collective whole (in the Jungian sense) was creating "strategies for overcoming the condition of disease" and trying to cure itself, by what he termed as "a reversion to archaic values." McKenna pointed to phenomena including surrealism, abstract expressionism, body piercing and tattooing, psychedelic drug use, sexual permissiveness, jazz, experimental dance, rave culture, rock and roll and catastrophe theory, amongst others, as his evidence that this process was underway.[83][84][85] This idea is linked to McKenna's "stoned ape" theory of human evolution, with him viewing the "archaic revival" as an impulse to return to the symbiotic and blissful relationship he believed humanity once had with the psilocybin mushroom.[26]

In differentiating his idea from the "New Age", a term that he felt trivialized the significance of the next phase in human evolution, McKenna stated that: "The New Age is essentially humanistic psychology '80s-style, with the addition of neo-shamanism, channeling, crystal and herbal healing. The archaic revival is a much larger, more global phenomenon that assumes that we are recovering the social forms of the late neolithic, and reaches far back in the 20th century to Freud, to surrealism, to abstract expressionism, even to a phenomenon like National Socialism which is a negative force. But the stress on ritual, on organized activity, on race/ancestor-consciousness – these are themes that have been worked out throughout the entire 20th century, and the archaic revival is an expression of that."[3][18]

Novelty theory and Timewave Zero

Novelty theory is a pseudoscientific idea[10][11] that purports to predict the ebb and flow of novelty in the universe as an inherent quality of time, proposing that time is not a constant but has various qualities tending toward either "habit" or "novelty".[5] Habit, in this context, can be thought of as entropic, repetitious, or conservative; and novelty as creative, disjunctive, or progressive phenomena.[8] McKenna's idea was that the universe is an engine designed for the production and conservation of novelty and that as novelty increases, so does complexity. With each level of complexity achieved becoming the platform for a further ascent into complexity.[8]

The basis of the theory was originally conceived in the mid-1970s after McKenna's experiences with psilocybin mushrooms at La Chorrera in the Amazon led him to closely study the King Wen sequence of the I Ching.[5][6][27]

In Asian Taoist philosophy the concept of opposing phenomena is represented by the yin and yang. Both are always present in everything, yet the amount of influence of each varies over time. The individual lines of the I Ching are made up of both Yin (broken lines) and Yang (solid lines).

When examining the King Wen sequence of the 64 hexagrams, McKenna noticed a pattern. He analysed the "degree of difference" between the hexagrams in each successive pair and claimed he found a statistical anomaly, which he believed suggested that the King Wen sequence was intentionally constructed,[5] with the sequence of hexagrams ordered in a highly structured and artificial way, and that this pattern codified the nature of time's flow in the world.[28] With the degrees of difference as numerical values, McKenna worked out a mathematical wave form based on the 384 lines of change that make up the 64 hexagrams. He was able to graph the data and this became the Novelty Time Wave.[5]

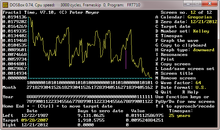

Peter J. Meyer (Peter Johann Gustav Meyer) (born 1946), in collaboration with McKenna, studied and improved the foundations of novelty theory, working out a mathematical formula and developing the Timewave Zero software (the original version of which was completed by July 1987),[86] enabling them to graph and explore its dynamics on a computer.[5][7] The graph was fractal: It exhibited a pattern in which a given small section of the wave was found to be identical in form to a larger section of the wave.[3][5] McKenna called this fractal modeling of time "temporal resonance", proposing it implied that larger intervals, occurring long ago, contained the same amount of information as shorter, more recent, intervals.[5][87] He suggested the up-and-down pattern of the wave shows an ongoing wavering between habit and novelty respectively. With each successive iteration trending, at an increasing level, towards infinite novelty. So according to novelty theory, the pattern of time itself is speeding up, with a requirement of the theory being that infinite novelty will be reached on a specific date.[3][5]

McKenna believed that notable events in history could be identified that would help him locate the time wave's end date[5] and attempted to find the best-fit placement when matching the graph to the data field of human history.[7] The last harmonic of the wave has a duration of 67.29 years.[88] Population growth, peak oil, and pollution statistics were some of the factors that pointed him to an early twenty-first century end date and when looking for an extremely novel event in human history as a signal that the final phase had begun McKenna picked the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.[5][88] This worked out to the graph reaching zero in mid-November 2012. When he later discovered that the end of the 13th baktun in the Maya calendar had been correlated by Western Maya scholars as December 21, 2012,[a] he adopted their end date instead.[5][94][b]

McKenna saw the universe, in relation to novelty theory, as having a teleological attractor at the end of time,[5] which increases interconnectedness and would eventually reach a singularity of infinite complexity. He also frequently referred to this as "the transcendental object at the end of time."[5][7] When describing this model of the universe he stated that: "The universe is not being pushed from behind. The universe is being pulled from the future toward a goal that is as inevitable as a marble reaching the bottom of a bowl when you release it up near the rim. If you do that, you know the marble will roll down the side of the bowl, down, down, down – until eventually it comes to rest at the lowest energy state, which is the bottom of the bowl. That's precisely my model of human history. I'm suggesting that the universe is pulled toward a complex attractor that exists ahead of us in time, and that our ever-accelerating speed through the phenomenal world of connectivity and novelty is based on the fact that we are now very, very close to the attractor."[95] Therefore, according to McKenna's final interpretation of the data and positioning of the graph, on December 21, 2012, we would have been in the unique position in time where maximum novelty would be experienced.[3][5][27] An event he described as a "concrescence",[12] a "tightening 'gyre'" with everything flowing together. Speculating that "when the laws of physics are obviated, the universe disappears, and what is left is the tightly bound plenum, the monad, able to express itself for itself, rather than only able to cast a shadow into physis as its reflection...It will be the entry of our species into 'hyperspace', but it will appear to be the end of physical laws, accompanied by the release of the mind into the imagination."[96]

Novelty theory is considered to be pseudoscience.[10][11] Among the criticisms are the use of numerology to derive dates of important events in world history,[11] the arbitrary rather than calculated end date of the time wave[26] and the apparent adjustment of the eschaton from November 2012 to December 2012 in order to coincide with the Maya calendar. Other purported dates do not fit the actual time frames: the date claimed for the emergence of Homo sapiens is inaccurate by 70,000 years, and the existence of the ancient Sumer and Egyptian civilisations contradict the date he gave for the beginning of "historical time". Some projected dates have been criticised for having seemingly arbitrary labels, such as the "height of the age of mammals"[11] and McKenna's analysis of historical events has been criticised for having a eurocentric and cultural bias.[6][26]

The Watkins Objection

The British mathematician Matthew Watkins of Exeter University conducted a mathematical analysis of the Time Wave, and claimed there were various mathematical flaws in its construction.[26]

Critical reception

One expert on drug treatment attacked McKenna for popularizing "dangerous substances." Judy Corman, vice president of Phoenix House of New York, a drug treatment center, said in a letter to The New York Times in 1993: "Surely the fact that Terence McKenna says that the psilocybin mushroom 'is the megaphone used by an alien, intergalactic Other to communicate with mankind' is enough for us to wonder if taking LSD has done something to his mental faculties."[17]

"I suffered hallucinatory agonies of my own while reading his shrilly ecstatic prose," Peter Conrad wrote in The New York Times in a 1993 review of McKenna's book True Hallucinations.[17]

Harvard University biologist Richard Evans Schultes wrote in American Scientist, in a 1993 review of McKenna's Food of the Gods, that the book was "a masterpiece of research and writing" and that it "should be read by every specialist working in the multifarious fields involved with the use of psychoactive drugs." Concluding that, "[i]t is, without question, destined to play a major role in our future considerations of the role of the ancient use of psychoactive drugs, the historical shaping of our modern concerns about drugs and perhaps about man's desire for escape from reality with drugs."[97]

John Horgan, in a 2012 blog post for Scientific American, also commented that Food of the Gods was "a rigorous argument...that mind-expanding plants and fungi catalyzed the transformation of our brutish ancestors into cultured modern humans."[8]

"To write him off as a crazy hippie is a rather lazy approach to a man not only full of fascinating ideas but also blessed with a sense of humor and self-parody," Tom Hodgkinson wrote in The New Statesman and Society in 1994.[17]

Mark Jacobson said of True Hallucinations, in a 1992 issue of Esquire Magazine that, "it would be hard to find a drug narrative more compellingly perched on a baroquely romantic limb than this passionate Tom-and-Huck-ride-great-mother-river-saga of brotherly bonding," adding "put simply, Terence is a hoot!"[6]

Wired called him a "charismatic talking head" who was "brainy, eloquent, and hilarious"[27] and Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead also said that he was "the only person who has made a serious effort to objectify the psychedelic experience."[17]

Bibliography

- McKenna, Dennis; McKenna, Terence (1975). The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching. New York: Seabury. ISBN 978-0-8164-9249-7.

- McKenna, Dennis; McKenna, Terence (1976). Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide. Under the pseudonyms OT Oss and ON Oeric. Berkeley, CA: And/Or Press. ISBN 978-0-915904-13-6.

- McKenna, Terence (1992a). The Archaic Revival: Speculations on Psychedelic Mushrooms, the Amazon, Virtual Reality, UFOs, Evolution, Shamanism, the Rebirth of the Goddess, and the End of History. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-06-250613-9.

- McKenna, Terence (1992b). Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge – A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution. New York: Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-07868-8.

- McKenna, Terence (1992). Synesthesia. Illustrated by Ely, Timothy C. New York: Granary Books. OCLC 30473682.

- Abraham, Ralph H.; McKenna, Terence; Sheldrake, Rupert (1992). Trialogues at the Edge of the West: Chaos, Creativity, and the Resacralization of the World. Forward by Houston, Jean. Bear & Company. ISBN 978-0-939680-97-9.

- McKenna, Terence (1993). True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author's Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil's Paradise. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-06-250545-3.

- Abraham, Ralph H.; McKenna, Terence; Sheldrake, Rupert (1998). The Evolutionary Mind: Conversations on Science, Imagination & Spirit. Monkfish Book Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9749359-7-3.

Spoken word

- History Ends in Green: Gaia, Psychedelics and the Archaic Revival, 6 audiocassette set, Mystic Fire audio, 1993, ISBN 978-1-56176-907-0 (recorded at the Esalen Institute, 1989)

- TechnoPagans at the End of History (transcription of rap with Mark Pesce from 1998)

- Psychedelics in the Age of Intelligent Machines (1999) (DVD) HPX/SurrealStudio

- Conversations on the Edge of Magic (1994) (CD & Cassette) ACE

- Rap-Dancing into the Third Millennium (1994) (Cassette) (Re-issued on CD as The Quintessential Hallucinogen) ACE

- Packing For the Long Strange Trip (1994) (Audio Cassette) ACE

- Global Perspectives and Psychedelic Poetics (1994) (Cassette) Sound Horizons Audio-Video, Inc.

- The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge (1992) (Cassette) Sounds True

- The Psychedelic Society (DVD & Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- True Hallucinations Workshop (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- The Vertigo at History's Edge: Who Are We? Where Have We Come From? Where Are We Going? (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Ethnobotany and Shamanism (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Shamanism, Symbiosis and Psychedelics Workshop (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Shamanology (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Shamanology of the Amazon (w/ Nicole Maxwell) (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Beyond Psychology (1983) (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Understanding & the Imagination in the Light of Nature Parts 1 & 2 (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Ethnobotany (a complete course given at The California Institute of Integral Studies) (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Non-ordinary States of Reality Through Vision Plants (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Mind & Time, Spirit & Matter: The Complete Weekend in Santa Fe (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Forms and Mysteries: Morphogenetic Fields and Psychedelic Experiences (w/ Rupert Sheldrake) (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- UFO: The Inside Outsider (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- A Calendar for The Goddess (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- A Magical Journey: Including Hallucinogens and Culture, Time and The I Ching, and The Human Future (Video Cassette) TAP/Sound Photosynthesis

- Aliens and Archetypes (Video Cassette) TAP/Sound Photosynthesis

- Angels, Aliens and Archetypes 1987 Symposium: Shamanic Approaches to the UFO, and Fairmont Banquet Talk (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Botanical Dimensions (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Conference on Botanical Intelligence (w/ Joan Halifax, Andy Weil, & Dennis McKenna) (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Coping With Gaia's Midwife Crisis (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Dreaming Awake at the End of Time (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Evolving Times (DVD, CD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Food of the Gods (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Food of the Gods 2: Drugs, Plants and Destiny (Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Hallucinogens in Shamanism & Anthropology at Bridge Psychedelic Conf.1991 (w/ Ralph Metzner, Marlene Dobkin De Rios, Allison Kennedy & Thomas Pinkson) (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Finale – Bridge Psychedelic Conf.1991 (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Man and Woman at the End of History (w/ Riane Eisler) (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Plants, Consciousness, and Transformation (1995) (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Metamorphosis (w/ Rupert Sheldrake & Ralph Abraham) (1995) (Video Cassette) Mystic Fire/Sound Photosynthesis

- Nature is the Center of the Mandala (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Opening the Doors of Creativity (1990) (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Places I Have Been (CD & Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Plants, Visions and History Lecture (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Psychedelics Before and After History (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Sacred Plants As Guides: New Dimensions of the Soul (at the Jung Society Clairemont, California) (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Seeking the Stone (Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Shamanism: Before and Beyond History – A Weekend at Ojai (w/ Ralph Metzner) (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Shedding the Monkey (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- State of the Stone '95 (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- The Ethnobotany of Shamanism Introductory Lecture: The Philosophical Implications of Psychobotony: Past, Present and Future (at CIIS) (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- The Ethnobotany of Shamanism Workshop: Psychedelics Before and After History (at CIIS) (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- The Grammar of Ecstasy – the World Within the Word (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- The Light at the End of History (Audio/Video Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- The State of the Stone Address: Having Archaic and Eating it Too (Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- The Taxonomy of Illusion (at UC Santa Cruz) (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- This World ...and Its Double (DVD & Video/Audio Cassette) Sound Photosynthesis

- Trialogues at the Edge of the Millennium (w/ Rupert Sheldrake & Ralph Abraham) (at UC Santa Cruz) (1998) (Video Cassette) Trialogue Press

Discography

- Re : Evolution with The Shamen (1992)

- Dream Matrix Telemetry with Zuvuya (1993)

- Alien Dreamtime with Spacetime Continuum & Stephen Kent (2003)

- "Reclaim Your Mind" with Mark Pontius (2020)[98]

Filmography

- Experiment at Petaluma (1990)

- Prague Gnosis: Terence McKenna Dialogues (1992)

- The Hemp Revolution (1995)

- Terence McKenna: The Last Word (1999)

- Shamans of the Amazon (2001)

- Alien Dreamtime (2003)

- 2012: The Odyssey (2007)

- The Alchemical Dream: Rebirth of the Great Work (2008)

- Manifesting the Mind (2009)

- Cognition Factor (2009)

- DMT: The Spirit Molecule (2010)

- 2012: Time for Change (2010)

- The Terence McKenna OmniBus (2012)

- The Transcendental Object at the End of Time (2014)

- Terence McKenna's True Hallucinations (2016)

See also

Notes

- ^ Most Mayanist scholars, such as Mark Van Stone and Anthony Aveni, adhere to the "GMT (Goodman-Martinez-Thompson) correlation" with the Long Count, which places the start date at 11 August 3114 BC and the end date of b'ak'tun 13 at December 21, 2012.[89] This date was also the overwhelming preference of those who believed in 2012 eschatology, arguably, Van Stone suggests, because it was a solstice, and was thus astrologically significant. Some Mayanist scholars, such as Michael D. Coe, Linda Schele and Marc Zender, adhere to the "Lounsbury/GMT+2" correlation, which sets the start date at August 13 and the end date at December 23. Which of these is the precise correlation has yet to be conclusively settled.[90] Coe's initial date was "24 December 2011." He revised it to "11 January AD 2013" in the 1980 2nd edition of his book,[91] not settling on December 23, 2012 until the 1984 3rd edition.[92] The correlation of b'ak'tun 13 as December 21, 2012 first appeared in Table B.2 of Robert J. Sharer's 1983 revision of the 4th edition of Sylvanus Morley's book The Ancient Maya.[93]

- ^ The 1975 first edition of McKenna's The Invisible Landscape refers to 2012 (but no specific day during the year) only twice. In the 1993 second edition, McKenna employed December 21, 2012 throughout, the date arrived at by the Mayanist researcher Robert J. Sharer.[94]

References

- ^ Znamenski, Andrei A. (2007). The Beauty of the Primitive: Shamanism and Western Imagination. Oxford University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-19-803849-8.

- ^ Horgan, John (2004). Rational Mysticism: Spirituality Meets Science in the Search for Enlightenment. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-547-34780-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Brown, David Jay; Novick, Rebecca McClen, eds. (1993). "Mushrooms, Elves And Magic". Mavericks of the Mind: Conversations for the New Millennium. Freedom, CA: Crossing Press. pp. 9–24. ISBN 978-0-89594-601-0.

- ^ a b Partridge, Christopher (2006). "Ch. 3: Cleansing the Doors of Perception: The Contemporary Sacralization of Psychedelics". Reenchantment of West. Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization, Popular Culture, and Occulture. Vol. 2. Continuum. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-567-55271-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Jenkins, John Major (2009). "Early 2012 Books McKenna and Waters". The 2012 Story: The Myths, Fallacies, and Truth Behind the Most Intriguing Date in History. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-14882-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Jacobson, Mark (June 1992). "Terence McKenna the brave prophet of The next psychedelic revolution, or is his cosmic egg just a little bit cracked?". Esquire. pp. 107–138. ESQ 1992 06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Dery, Mark (2001) [1996]. "Terence McKenna: The inner elf". 21•C Magazine. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Horgan, John. "Was psychedelic guru Terence McKenna goofing about 2012 prophecy?" (blog). Scientific American. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Krupp, E.C. (November 2009). "The great 2012 scare" (PDF). Sky & Telescope. pp. 22–26 [25]. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Bruce, Alexandra (2009). 2012: Science Or Superstition (The Definitive Guide to the Doomsday Phenomenon). Disinformation Movie & Book Guides. Red Wheel Weiser. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-934708-51-4.

- ^ a b c d e Normark, Johan (June 16, 2009). "2012: Prophet of nonsense #8: Terence McKenna – Novelty theory and timewave zero". Archaeological Haecceities (blog).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pinchbeck, Daniel (2003). Breaking Open the Head: A Psychedelic Journey into the Heart of Contemporary Shamanism. Broadway Books. pp. 231–38. ISBN 978-0-7679-0743-9.

- ^ a b c d Kent, James (December 2, 2003). "Terence McKenna Interview, Part 1". Tripzine.com. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ Dennis McKenna (2012). The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss: My Life with Terence McKenna (ebook) (1st ed.). Polaris Publications. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-87839-637-5.

- ^ McKenna, Dennis 2012, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e Lin, Tao (August 13, 2014). "Psilocybin, the Mushroom, and Terence McKenna". Vice. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Martin, Douglas (September 10, 2013). "Terence McKenna, 53, dies; Patron of psychedelic drugs". The New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c McKenna 1992a, pp. 204–17.

- ^ a b c McKenna 1993, p. 215.

- ^ a b McKenna 1993, pp. 55–58.

- ^ a b McKenna 1993, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Terence McKenna; Promoter of psychedelic drug use". Los Angeles Times. April 7, 2000. p. B6.

- ^ a b "Terence McKenna". Omni. Vol. 15, no. 7. 1993. pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c McKenna 1993, pp. 1–13.

- ^ McKenna 1993, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Letcher, Andy (2007). "14.The Elf-Clowns of Hyperspace". Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom. Harper Perennial. pp. 253–74. ISBN 978-0-06-082829-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Davis, Erik (May 2000). "Terence McKenna's last trip". Wired. Vol. 8, no. 5. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Gyus. "The End of the River: A critical view of Linear Apocalyptic Thought, and how Linearity makes a sneak appearance in Timewave Theory's fractal view of Time…". dreamflesh. The Unlimited Dream Company. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ McKenna 1993, p. 194.

- ^ McKenna 1993, p. 3.

- ^ a b McKenna 1993, pp. 205–07.

- ^ a b c Hancock, Graham (2006) [2005 Hancock]. Supernatural: Meetings with the Ancient Teachers of Mankind. London: Arrow. pp. 556–57. ISBN 978-0-09-947415-9.

- ^ a b Letcher 2007, p. 278.

- ^ Ott J. (1993). Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic Drugs, their Plant Sources and History. Kennewick, Washington: Natural Products Company. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-9614234-3-8.; see San Antonio JP. (1971). "A laboratory method to obtain fruit from cased grain spawn of the cultivated mushroom, Agaricus bisporus". Mycologia. 63 (1): 16–21. doi:10.2307/3757680. JSTOR 3757680. PMID 5102274.

- ^ McKenna & McKenna 1976, Preface (revised ed.).

- ^ Wojtowicz, Slawek (2008). "Ch. 6: Magic Mushrooms". In Strassman, Rick; Wojtowicz, Slawek; Luna, Luis Eduardo; et al. (eds.). Inner Paths To Outer Space: Journeys to Alien Worlds Through Psychedelics and Other Spiritual Technologies. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-59477-224-5.

- ^ a b c Toop, David (February 18, 1993). "Sounds like a radical vision; The Shamen and Terence McKenna". Rock Music. The Times.

- ^ Sharkey, Alix (April 15, 2000). "Terence McKenna". The Independent (Obituary). p. 7.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1994). "181-McKennaErosEschatonQA". In Hagerty, Lorenzo (ed.). Psychedelia: Psychedelic Salon ALL Episodes (MP3) (lecture). Event occurs at 32:00. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (September 11, 1993a). This World...and Its Double (DVD). Mill Valley, California: Sound Photosynthesis. Event occurs at 1:30:45.

- ^ Leary, Timothy (1992). "Unfolding the Stone 1". In Damer, Bruce (ed.). Psychedelia: Raw Archives of Terence McKenna Talks (MP3) (Introduction to lecture by Terence McKenna). Event occurs at 2:08.

- ^ Hicks, Bill (1997) [November 1992 – December 1993]. "Pt. 1: Ch. 2: Gifts of Forgiveness". Rant in E-Minor (CD and MP3). Rykodisc. Event occurs at 0:58. OCLC 38306915.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gyrus (2009). "Appendix II: The Stoned Ape Hypothesis". War and the Noble Savage: A Critical Inquiry Into Recent Accounts of Violence Amongst Uncivilized Peoples. London: Dreamflesh. pp. 63–66. ISBN 978-0-9554196-1-4.

- ^ Hayes, Charles (2000). Tripping: An Anthology of True-Life Psychedelic Adventures. Penguin. p. 1201. ISBN 978-1-101-15719-0.

- ^ a b Abraham, McKenna & Sheldrake 1998, Preface.

- ^ Abraham, McKenna & Sheldrake 1992, p. 11.

- ^ Rice, Paddy Rose (ed.). "The Sheldrake – McKenna – Abraham Trialogues". sheldrake.org. Archived from the original on November 28, 2013.

- ^ a b "Who We Are & Library Hours/Contact Info". Botanical Dimensions.

- ^ a b "Plants and People: Our Ethnobotany Offerings". Botanical Dimensions.

- ^ Nollman, Jim (1994). Why We Garden: Cultivating a sense of place. Henry Holt and Company. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8050-2719-8.

- ^ Davis, Erik (January 13, 2005). "Terence McKenna Vs. the Black Hole". techgnosis.com (Excerpts from the CD, Terence McKenna: The Last Interview). Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Frauenfelder, Mark (February 22, 2007). "Terence McKenna's library destroyed in fire". Boing Boing (group blog). Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Davis, Erik. "Terence McKenna's Ex-Library". Internet Archive. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ a b 'The Butterfly Hunter' by Klea McKenna By Tao Lin, Sep 9 2014, 7:36pm, Vice

- ^ a b Stamets, Paul (1996). "5. Good tips for great trips". Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World: An identification guide. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-89815-839-7.

- ^ McKenna 1992a, p. 43.

- ^ Wadsworth, Jennifer (May 11, 2016). "Federal approval brings MDMA from club to clinic". Metro Active. Metro Silicon Valley. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ Pinchbeck 2003, p. 193.

- ^ McKenna, Terence. "The Invisible Landscape". futurehi.net (lecture). Future Hi. Archived from the original on October 16, 2005.[verification needed][infringing link?]

- ^ Pinchbeck 2003, p. 247.

- ^ Trip, Gabriel (May 2, 1993). "Tripping, but not falling". New York Times. p. A6.

- ^ Shamen (1992). "Re: Evolution". Boss Drum (CD, MP3). Epic. Event occurs at 4:50. OCLC 27056837. Track 10.

- ^ McKenna, Terence. "The Gaian mind". deoxy.org. Archived from the original on February 3, 1999. – Cut-up from the works of Terence McKenna.

- ^ Rick Strassman, M.D. (2001). DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A doctor's revolutionary research into the biology of near-death and mystical experiences (Later printing ed.). Inner Traditions Bear and Company. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-89281-927-0.

- ^ Pinchbeck 2003, p. 213.

- ^ Pinchbeck 2003, p. 234.

- ^ Rabey, Steve (August 13, 1994). "Instant karma: Psychedelic drug use on the rise as a quick route to spirituality". Colorado Springs Gazette – Telegraph. p. E1.

- ^ McKenna 1992a, p. 242.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1999). Psychedelics in the age of intelligent machines (lecture) (video).

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1992). "Unfolding the Stone 1". In Damer, Bruce (ed.). Psychedelia: Raw Archives of Terence McKenna Talks (lecture) (MP3). Event occurs at 17:30.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1990–1999). "Surfing Finnegans Wake". In Damer, Bruce (ed.). Psychedelia: Raw archives of Terence McKenna talks (lecture) (MP3). Event occurs at 0:45.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1991). "Afterword: I understand Philip K. Dick". In Sutin, Lawrence (ed.). In Pursuit of Valis: Selections from the exegesis. Underwood-Miller. ISBN 978-0-88733-091-9. "Convenience copy". sirbacon.org.[verification needed][infringing link?]

- ^ a b Mulvihill, Tom. "Eight things you didn't know about magic mushrooms". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ a b McKenna 1992b, pp. 56–60.

- ^ McKenna 1992b, p. 54.

- ^ Fischer, Roland; Hill, Richard; Thatcher, Karen; Scheib, James (1970). "Psilocybin-Induced contraction of nearby visual space". Agents and Actions. 1 (4): 190–97. doi:10.1007/BF01965761. PMID 5520365. S2CID 8321037.

- ^ McKenna 1992b, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Znamenski 2007, pp. 138–39.

- ^ a b McKenna 1992b, p. 59.

- ^ Pinchbeck 2003, p. 194.

- ^ Akers, Brian P. (March 28, 2011). "Concerning Terence McKenna's 'Stoned Apes'". Reality Sandwich. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Hayes, Charles (2000). "Introduction: The Psychedelic [in] Society: A Brief Cultural History of Tripping". Tripping: An Anthology of True-Life Psychedelic Adventures. Penguin. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-101-15719-0.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1994). "181-McKennaErosEschatonQA". In Hagerty, Lorenzo (ed.). Psychedelia: Psychedelic Salon ALL Episodes (MP3) (lecture). Event occurs at 49:10. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ McKenna, Terence. "The Importance of Human Beings (a.k.a Eros and the Eschaton)". matrixmasters.net.

- ^ Spacetime Continuum; McKenna, Terence; Kent, Stephen (2003) [1993]. "Archaic Revival". Alien Dreamtime. Visuals by Rose-X Media House. Magic Carpet Media: Astralwerks. Event occurs at 3:08. OCLC 80061092. Archived from the original (DVD, CD and MP3) on July 6, 1997. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ United States Copyright Office Title=Timewave zero. Copyright Number: TXu000288739 Date: 1987

- ^ McKenna 1992a, pp. 104–13.

- ^ a b Abraham, Ralph; McKenna, Terence (June 1983). "Dynamics of Hyperspace". ralph-abraham.org. Santa Cruz, CA. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ Matthews, Peter (2005). "Who's Who in the Classic Maya World". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Van Stone, Mark. "Questions and comments". famsi.org. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ Coe, Michael D. (1980). The Maya. Ancient Peoples and Places. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. p. 151.

- ^ Coe, Michael D. (1984). The Maya. Ancient Peoples and Places (3rd ed.). London: Thames and Hudson.

- ^ Morley, Sylvanus (1983). The Ancient Maya (4th ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 603, Table B2. ISBN 9780804711371.

- ^ a b Defesche, Sacha (June 17, 2008) [January–August 2007]. "'The 2012 Phenomenon': A historical and typological approach to a modern apocalyptic mythology" (MA Thesis, Mysticism and Western Esotericism, University of Amsterdam). Skepsis. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1994). "Approaching Timewave Zero". Magical Blend. No. 44. Retrieved June 15, 2015.[reprint verification needed][infringing link?]

- ^ McKenna 1992a, p. 101.

- ^ Schultes, Richard Evans (1993). "Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge by Terence McKenna". Life Sciences. American Scientist (Book review). Vol. 81, no. 5. pp. 489–90. JSTOR 29775027.

- ^ "Literally What do You Want?".

External links

- Terence McKenna at IMDb

- Botanical Dimensions

- Dunning, Brian (June 30, 2020). 4734 "Skeptoid #734: The Stoned Ape Theory". Skeptoid.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Erowid's Terence McKenna Vault

- Official website

- Psychedelic Salon, Over 100 podcasts of Terence McKenna lectures

- Tao of Terence, a 12-part series of essays on McKenna by Tao Lin at Vice

- Terence McKenna Bibliography, list of references to books, articles, audio, video, interviews and translations by and about Terence McKenna

- Terrence McKenna's True Hallucinations Documentary by Peter Bergmann

- The Transcendental Object At The End Of Time Documentary by Peter Bergmann