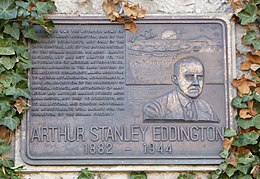

Arthur Eddington

Arthur Eddington | |

|---|---|

Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882–1944) | |

| Born | Arthur Stanley Eddington 28 December 1882 Kendal, Westmorland, England, United Kingdom |

| Died | 22 November 1944 (aged 61) Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | English |

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater | University of Manchester Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Eddington approximation Eddington experiment Eddington limit Eddington number Eddington valve Eddington–Dirac number Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates Eddington–Sweet circulation |

| Awards | Royal Society Royal Medal (1928) Smith's Prize (1907) RAS Gold Medal (1924) Henry Draper Medal (1924) Bruce Medal (1924) Knights Bachelor (1930) Order of Merit (1938) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astrophysics |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Academic advisors | |

| Doctoral students | Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar[1] Leslie Comrie Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin Hermann Bondi |

| Other notable students | Georges Lemaître |

| Influences | Horace Lamb Arthur Schuster John William Graham |

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington OM FRS[2] (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He was also a philosopher of science and a populariser of science. The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the luminosity of stars, or the radiation generated by accretion onto a compact object, is named in his honour.

Around 1920, he anticipated the discovery and mechanism of nuclear fusion processes in stars, in his paper "The Internal Constitution of the Stars".[3][4] At that time, the source of stellar energy was a complete mystery; Eddington was the first to correctly speculate that the source was fusion of hydrogen into helium.

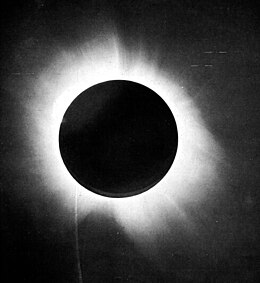

Eddington wrote a number of articles that announced and explained Einstein's theory of general relativity to the English-speaking world. World War I had severed many lines of scientific communication, and new developments in German science were not well known in England. He also conducted an expedition to observe the solar eclipse of 29 May 1919 that provided one of the earliest confirmations of general relativity, and he became known for his popular expositions and interpretations of the theory.

Early years[edit]

Eddington was born 28 December 1882 in Kendal, Westmorland (now Cumbria), England, the son of Quaker parents, Arthur Henry Eddington, headmaster of the Quaker School, and Sarah Ann Shout.[5]

His father taught at a Quaker training college in Lancashire before moving to Kendal to become headmaster of Stramongate School. He died in the typhoid epidemic which swept England in 1884. His mother was left to bring up her two children with relatively little income. The family moved to Weston-super-Mare where at first Stanley (as his mother and sister always called Eddington) was educated at home before spending three years at a preparatory school. The family lived at a house called Varzin, 42 Walliscote Road, Weston-super-Mare. There is a commemorative plaque on the building explaining Sir Arthur's contribution to science.

In 1893 Eddington entered Brynmelyn School. He proved to be a most capable scholar, particularly in mathematics and English literature. His performance earned him a scholarship to Owens College, Manchester (what was later to become the University of Manchester) in 1898, which he was able to attend, having turned 16 that year. He spent the first year in a general course, but turned to physics for the next three years. Eddington was greatly influenced by his physics and mathematics teachers, Arthur Schuster and Horace Lamb. At Manchester, Eddington lived at Dalton Hall, where he came under the lasting influence of the Quaker mathematician J. W. Graham. His progress was rapid, winning him several scholarships and he graduated with a BSc in physics with First Class Honours in 1902.

Based on his performance at Owens College, he was awarded a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1902. His tutor at Cambridge was Robert Alfred Herman and in 1904 Eddington became the first ever second-year student to be placed as Senior Wrangler. After receiving his M.A. in 1905, he began research on thermionic emission in the Cavendish Laboratory. This did not go well, and meanwhile he spent time teaching mathematics to first year engineering students. This hiatus was brief. Through a recommendation by E. T. Whittaker, his senior colleague at Trinity College, he secured a position at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich where he was to embark on his career in astronomy, a career whose seeds had been sown even as a young child when he would often "try to count the stars".[6]

Astronomy[edit]

In January 1906, Eddington was nominated to the post of chief assistant to the Astronomer Royal at the Royal Greenwich Observatory. He left Cambridge for Greenwich the following month. He was put to work on a detailed analysis of the parallax of 433 Eros on photographic plates that had started in 1900. He developed a new statistical method based on the apparent drift of two background stars, winning him the Smith's Prize in 1907. The prize won him a Fellowship of Trinity College, Cambridge. In December 1912 George Darwin, son of Charles Darwin, died suddenly and Eddington was promoted to his chair as the Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy in early 1913. Later that year, Robert Ball, holder of the theoretical Lowndean chair also died, and Eddington was named the director of the entire Cambridge Observatory the next year. In May 1914 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society: he was awarded the Royal Medal in 1928 and delivered the Bakerian Lecture in 1926.[7]

Eddington also investigated the interior of stars through theory, and developed the first true understanding of stellar processes. He began this in 1916 with investigations of possible physical explanations for Cepheid variable stars. He began by extending Karl Schwarzschild's earlier work on radiation pressure in Emden polytropic models. These models treated a star as a sphere of gas held up against gravity by internal thermal pressure, and one of Eddington's chief additions was to show that radiation pressure was necessary to prevent collapse of the sphere. He developed his model despite knowingly lacking firm foundations for understanding opacity and energy generation in the stellar interior. However, his results allowed for calculation of temperature, density and pressure at all points inside a star (thermodynamic anisotropy), and Eddington argued that his theory was so useful for further astrophysical investigation that it should be retained despite not being based on completely accepted physics. James Jeans contributed the important suggestion that stellar matter would certainly be ionized, but that was the end of any collaboration between the pair, who became famous for their lively debates.

Eddington defended his method by pointing to the utility of his results, particularly his important mass–luminosity relation. This had the unexpected result of showing that virtually all stars, including giants and dwarfs, behaved as ideal gases. In the process of developing his stellar models, he sought to overturn current thinking about the sources of stellar energy. Jeans and others defended the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism, which was based on classical mechanics, while Eddington speculated broadly about the qualitative and quantitative consequences of possible proton–electron annihilation and nuclear fusion processes.

Around 1920, he anticipated the discovery and mechanism of nuclear fusion processes in stars, in his paper The Internal Constitution of the Stars.[3][4] At that time, the source of stellar energy was a complete mystery; Eddington correctly speculated that the source was fusion of hydrogen into helium, liberating enormous energy according to Einstein's equation E = mc2. This was a particularly remarkable development since at that time fusion and thermonuclear energy, and even the fact that stars are largely composed of hydrogen (see metallicity), had not yet been discovered. Eddington's paper, based on knowledge at the time, reasoned that:

- The leading theory of stellar energy, the contraction hypothesis, should cause stars' rotation to visibly speed up due to conservation of angular momentum. But observations of Cepheid variable stars showed this was not happening.

- The only other known plausible source of energy was conversion of matter to energy; Einstein had shown some years earlier that a small amount of matter was equivalent to a large amount of energy.

- Francis Aston had also recently shown that the mass of a helium atom was about 0.8% less than the mass of the four hydrogen atoms which would, combined, form a helium atom, suggesting that if such a combination could happen, it would release considerable energy as a byproduct.

- If a star contained just 5% of fusible hydrogen, it would suffice to explain how stars got their energy. (We now know that most "ordinary" stars contain far more than 5% hydrogen.)

- Further elements might also be fused, and other scientists had speculated that stars were the "crucible" in which light elements combined to create heavy elements, but without more accurate measurements of their atomic masses nothing more could be said at the time.

All of these speculations were proven correct in the following decades.

With these assumptions, he demonstrated that the interior temperature of stars must be millions of degrees. In 1924, he discovered the mass–luminosity relation for stars (see Lecchini in § Further reading). Despite some disagreement, Eddington's models were eventually accepted as a powerful tool for further investigation, particularly in issues of stellar evolution. The confirmation of his estimated stellar diameters by Michelson in 1920 proved crucial in convincing astronomers unused to Eddington's intuitive, exploratory style. Eddington's theory appeared in mature form in 1926 as The Internal Constitution of the Stars, which became an important text for training an entire generation of astrophysicists.

Eddington's work in astrophysics in the late 1920s and the 1930s continued his work in stellar structure, and precipitated further clashes with Jeans and Edward Arthur Milne. An important topic was the extension of his models to take advantage of developments in quantum physics, including the use of degeneracy physics in describing dwarf stars.

Dispute with Chandrasekhar on existence of black holes[edit]

The topic of extension of his models precipitated his dispute with Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, who was then a student at Cambridge. Chandrasekhar's work presaged the discovery of black holes, which at the time seemed so absurdly non-physical that Eddington refused to believe that Chandrasekhar's purely mathematical derivation had consequences for the real world. Eddington was wrong and his motivation is controversial. Chandrasekhar's narrative of this incident, in which his work is harshly rejected, portrays Eddington as rather cruel, dogmatic, and racist. Eddington's criticism seems to have been based partly on a suspicion that a purely mathematical derivation from relativity theory was not enough to explain the seemingly daunting physical paradoxes that were inherent to degenerate stars, but to have "raised irrelevant objections" in addition, as Thanu Padmanabhan puts it.[8]

Relativity[edit]

During World War I, Eddington was Secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society, which meant he was the first to receive a series of letters and papers from Willem de Sitter regarding Einstein's theory of general relativity. Eddington was fortunate in being not only one of the few astronomers with the mathematical skills to understand general relativity, but owing to his internationalist and pacifist views inspired by his Quaker religious beliefs,[6][9] one of the few at the time who was still interested in pursuing a theory developed by a German physicist. He quickly became the chief supporter and expositor of relativity in Britain. He and Astronomer Royal Frank Watson Dyson organized two expeditions to observe a solar eclipse in 1919 to make the first empirical test of Einstein's theory: the measurement of the deflection of light by the sun's gravitational field. In fact, Dyson's argument for the indispensability of Eddington's expertise in this test was what prevented Eddington from eventually having to enter military service.[6][9]

When conscription was introduced in Britain on 2 March 1916, Eddington intended to apply for an exemption as a conscientious objector.[6] Cambridge University authorities instead requested and were granted an exemption on the ground of Eddington's work being of national interest. In 1918, this was appealed against by the Ministry of National Service. Before the appeal tribunal in June, Eddington claimed conscientious objector status, which was not recognized and would have ended his exemption in August 1918. A further two hearings took place in June and July, respectively. Eddington's personal statement at the June hearing about his objection to war based on religious grounds is on record.[6] The Astronomer Royal, Sir Frank Dyson, supported Eddington at the July hearing with a written statement, emphasising Eddington's essential role in the solar eclipse expedition to Príncipe in May 1919. Eddington made clear his willingness to serve in the Friends' Ambulance Unit, under the jurisdiction of the British Red Cross, or as a harvest labourer. However, the tribunal's decision to grant a further twelve months' exemption from military service was on condition of Eddington continuing his astronomy work, in particular in preparation for the Príncipe expedition.[6][9] The war ended before the end of his exemption.

After the war, Eddington travelled to the island of Príncipe off the west coast of Africa to watch the solar eclipse of 29 May 1919. During the eclipse, he took pictures of the stars (several stars in the Hyades cluster include Kappa Tauri of the constellation Taurus) in the region around the Sun.[10] According to the theory of general relativity, stars with light rays that passed near the Sun would appear to have been slightly shifted because their light had been curved by its gravitational field. This effect is noticeable only during eclipses, since otherwise the Sun's brightness obscures the affected stars. Eddington showed that Newtonian gravitation could be interpreted to predict half the shift predicted by Einstein.

Eddington's observations published the next year[10] confirmed Einstein's theory, and were hailed at the time as evidence of general relativity over the Newtonian model. The news was reported in newspapers all over the world as a major story. Afterward, Eddington embarked on a campaign to popularize relativity and the expedition as landmarks both in scientific development and international scientific relations.

It has been claimed that Eddington's observations were of poor quality, and he had unjustly discounted simultaneous observations at Sobral, Brazil, which appeared closer to the Newtonian model, but a 1979 re-analysis with modern measuring equipment and contemporary software validated Eddington's results and conclusions.[11] The quality of the 1919 results was indeed poor compared to later observations, but was sufficient to persuade contemporary astronomers. The rejection of the results from the Brazil expedition was due to a defect in the telescopes used which, again, was completely accepted and well understood by contemporary astronomers.[12]

Throughout this period, Eddington lectured on relativity, and was particularly well known for his ability to explain the concepts in lay terms as well as scientific. He collected many of these into the Mathematical Theory of Relativity in 1923, which Albert Einstein suggested was "the finest presentation of the subject in any language." He was an early advocate of Einstein's General Relativity, and an interesting anecdote well illustrates his humour and personal intellectual investment: Ludwik Silberstein, a physicist who thought of himself as an expert on relativity, approached Eddington at the Royal Society's (6 November) 1919 meeting where he had defended Einstein's Relativity with his Brazil-Príncipe Solar Eclipse calculations with some degree of scepticism, and ruefully charged Arthur as one who claimed to be one of three men who actually understood the theory (Silberstein, of course, was including himself and Einstein as the other). When Eddington refrained from replying, he insisted Arthur not be "so shy", whereupon Eddington replied, "Oh, no! I was wondering who the third one might be!"[13]

Cosmology[edit]

Eddington was also heavily involved with the development of the first generation of general relativistic cosmological models. He had been investigating the instability of the Einstein universe when he learned of both Lemaître's 1927 paper postulating an expanding or contracting universe and Hubble's work on the recession of the spiral nebulae. He felt the cosmological constant must have played the crucial role in the universe's evolution from an Einsteinian steady state to its current expanding state, and most of his cosmological investigations focused on the constant's significance and characteristics. In The Mathematical Theory of Relativity, Eddington interpreted the cosmological constant to mean that the universe is "self-gauging".

Fundamental theory and the Eddington number[edit]

During the 1920s until his death, Eddington increasingly concentrated on what he called "fundamental theory" which was intended to be a unification of quantum theory, relativity, cosmology, and gravitation. At first he progressed along "traditional" lines, but turned increasingly to an almost numerological analysis of the dimensionless ratios of fundamental constants.

His basic approach was to combine several fundamental constants in order to produce a dimensionless number. In many cases these would result in numbers close to 1040, its square, or its square root. He was convinced that the mass of the proton and the charge of the electron were a natural and complete specification for constructing a Universe and that their values were not accidental. One of the discoverers of quantum mechanics, Paul Dirac, also pursued this line of investigation, which has become known as the Dirac large numbers hypothesis[14] A somewhat damaging statement in his defence of these concepts involved the fine-structure constant, α. At the time it was measured to be very close to 1/136, and he argued that the value should in fact be exactly 1/136 for epistemological reasons. Later measurements placed the value much closer to 1/137, at which point he switched his line of reasoning to argue that one more should be added to the degrees of freedom, so that the value should in fact be exactly 1/137, the Eddington number.[15] Wags at the time started calling him "Arthur Adding-one".[16] This change of stance detracted from Eddington's credibility in the physics community. The current measured value is estimated at 1/137.035 999 074(44).

Eddington believed he had identified an algebraic basis for fundamental physics, which he termed "E-numbers" (representing a certain group – a Clifford algebra). These in effect incorporated spacetime into a higher-dimensional structure. While his theory has long been neglected by the general physics community, similar algebraic notions underlie many modern attempts at a grand unified theory. Moreover, Eddington's emphasis on the values of the fundamental constants, and specifically upon dimensionless numbers derived from them, is nowadays a central concern of physics. In particular, he predicted a number of hydrogen atoms in the Universe 136 × 2256 ≈ 1.57 1079, or equivalently the half of the total number of particles protons + electrons.[17] He did not complete this line of research before his death in 1944; his book Fundamental Theory was published posthumously in 1948.

Eddington number for cycling[edit]

Eddington is credited with devising a measure of a cyclist's long-distance riding achievements. The Eddington number in the context of cycling is defined as the maximum number E such that the cyclist has cycled E miles on E days.[18][19]

For example, an Eddington number of 70 miles would imply that the cyclist has cycled at least 70 miles in a day on at least 70 occasions. Achieving a high Eddington number is difficult since moving from, say, 70 to 75 will (probably) require more than five new long distance rides, since any rides shorter than 75 miles will no longer be included in the reckoning. Eddington's own life-time E-number was 84.[20]

The Eddington number for cycling is analogous to the h-index that quantifies both the actual scientific productivity and the apparent scientific impact of a scientist.

The Eddington Number for cycling involves units of both distance and time. The significance of E is tied to its units. For example, in cycling an E of 62 miles means a cyclist has covered 62 miles at least 62 times. The distance 62 miles is equivalent to 100 kilometers. However, an E of 62 miles may not be equivalent to an E of 100 kilometers. A cyclist with an E of 100 kilometers would mean 100 or more rides of at least 100 kilometers were done. While the distances 100 kilometers and 62 miles are equivalent, an E of 100 kilometers would require 38 more rides of that length than an E of 62 miles.

Philosophy[edit]

Idealism[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Eddington wrote in his book The Nature of the Physical World that "The stuff of the world is mind-stuff."

The idealist conclusion was not integral to his epistemology but was based on two main arguments.

The first derives directly from current physical theory. Briefly, mechanical theories of the ether and of the behaviour of fundamental particles have been discarded in both relativity and quantum physics. From this, Eddington inferred that a materialistic metaphysics was outmoded and that, in consequence, since the disjunction of materialism or idealism are assumed to be exhaustive, an idealistic metaphysics is required. The second, and more interesting argument, was based on Eddington's epistemology, and may be regarded as consisting of two parts. First, all we know of the objective world is its structure, and the structure of the objective world is precisely mirrored in our own consciousness. We therefore have no reason to doubt that the objective world too is "mind-stuff". Dualistic metaphysics, then, cannot be evidentially supported.

But, second, not only can we not know that the objective world is nonmentalistic, we also cannot intelligibly suppose that it could be material. To conceive of a dualism entails attributing material properties to the objective world. However, this presupposes that we could observe that the objective world has material properties. But this is absurd, for whatever is observed must ultimately be the content of our own consciousness, and consequently, nonmaterial.

Ian Barbour, in his book Issues in Science and Religion (1966), p. 133, cites Eddington's The Nature of the Physical World (1928) for a text that argues the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principles provides a scientific basis for "the defense of the idea of human freedom" and his Science and the Unseen World (1929) for support of philosophical idealism "the thesis that reality is basically mental".

Charles De Koninck points out that Eddington believed in objective reality existing apart from our minds, but was using the phrase "mind-stuff" to highlight the inherent intelligibility of the world: that our minds and the physical world are made of the same "stuff" and that our minds are the inescapable connection to the world.[21] As De Koninck quotes Eddington,

Indeterminism[edit]

Against Albert Einstein and others who advocated determinism, indeterminism—championed by Eddington[21]—says that a physical object has an ontologically undetermined component that is not due to the epistemological limitations of physicists' understanding. The uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics, then, would not necessarily be due to hidden variables but to an indeterminism in nature itself.

Popular and philosophical writings[edit]

Eddington wrote a parody of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, recounting his 1919 solar eclipse experiment. It contained the following quatrain:[22]

During the 1920s and 30s, Eddington gave numerous lectures, interviews, and radio broadcasts on relativity, in addition to his textbook The Mathematical Theory of Relativity, and later, quantum mechanics. Many of these were gathered into books, including The Nature of the Physical World and New Pathways in Science. His use of literary allusions and humour helped make these difficult subjects more accessible.

Eddington's books and lectures were immensely popular with the public, not only because of his clear exposition, but also for his willingness to discuss the philosophical and religious implications of the new physics. He argued for a deeply rooted philosophical harmony between scientific investigation and religious mysticism, and also that the positivist nature of relativity and quantum physics provided new room for personal religious experience and free will. Unlike many other spiritual scientists, he rejected the idea that science could provide proof of religious propositions.

He is sometimes misunderstood[by whom?] as having promoted the infinite monkey theorem in his 1928 book The Nature of the Physical World, with the phrase "If an army of monkeys were strumming on typewriters, they might write all the books in the British Museum". It is clear from the context that Eddington is not suggesting that the probability of this happening is worthy of serious consideration. On the contrary, it was a rhetorical illustration of the fact that below certain levels of probability, the term improbable is functionally equivalent to impossible.

His popular writings made him a household name in Great Britain between the world wars.

Death[edit]

Eddington died of cancer in the Evelyn Nursing Home, Cambridge, on 22 November 1944.[23] He was unmarried. His body was cremated at Cambridge Crematorium (Cambridgeshire) on 27 November 1944; the cremated remains were buried in the grave of his mother in the Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge.

Cambridge University's North West Cambridge Development has been named "Eddington" in his honour.

The actor Paul Eddington was a relative, mentioning in his autobiography (in light of his own weakness in mathematics) "what I then felt to be the misfortune" of being related to "one of the foremost physicists in the world".[24]

Obituaries[edit]

- Obituary 1 by Henry Norris Russell, Astrophysical Journal 101 (1943–46) 133

- Obituary 2 by A. Vibert Douglas, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 39 (1943–46) 1

- Obituary 3 by Harold Spencer Jones and E. T. Whittaker, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 105 (1943–46) 68

- Obituary 4 by Herbert Dingle, The Observatory 66 (1943–46) 1

- The Times, Thursday, 23 November 1944; pg. 7; Issue 49998; col D: Obituary (unsigned) – Image of cutting available at O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Arthur Eddington", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

Honours[edit]

Awards

| Named after him

| Service

|

In popular culture[edit]

- Eddington is a central figure in the short story "The Mathematician's Nightmare: The Vision of Professor Squarepunt" by Bertrand Russell, a work featured in The Mathematical Magpie by Clifton Fadiman.

- He was portrayed by David Tennant in the television film Einstein and Eddington, a co-production of the BBC and HBO, broadcast in the United Kingdom on Saturday, 22 November 2008, on BBC2.

- His thoughts on humour and religious experience were quoted in the adventure game The Witness, a production of the Thelka, Inc., released on 26 January 2016.

- Time placed him on the cover on 16 April 1934.[29]

Publications[edit]

- 1914. Stellar Movements and the Structure of the Universe. London: Macmillan.

- 1918. Report on the relativity theory of gravitation. London, Fleetway press, Ltd.

- 1920. Space, Time and Gravitation: An Outline of the General Relativity Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33709-7

- 1923, 1952. The Mathematical Theory of Relativity. Cambridge University Press.

- 1925. The Domain of Physical Science. 2005 reprint: ISBN 1-4253-5842-X

- 1926. Stars and Atoms. Oxford: British Association.

- 1926. The Internal Constitution of Stars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33708-9

- 1928. The Nature of the Physical World. MacMillan. 1935 replica edition: ISBN 0-8414-3885-4, University of Michigan 1981 edition: ISBN 0-472-06015-5 (1926–27 Gifford lectures)

- 1929. Science and the Unseen World. US Macmillan, UK Allen & Unwin. 1980 Reprint Arden Library ISBN 0-8495-1426-6. 2004 US reprint — Whitefish, Montana : Kessinger Publications: ISBN 1-4179-1728-8. 2007 UK reprint London, Allen & Unwin ISBN 978-0-901689-81-8 (Swarthmore Lecture), with a new foreword by George Ellis.

- 1930. Why I Believe in God: Science and Religion, as a Scientist Sees It. Arrow/scrollable preview.

- 1933. The Expanding Universe: Astronomy's 'Great Debate', 1900–1931. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34976-1

- 1935. New Pathways in Science. Cambridge University Press.

- 1936. Relativity Theory of Protons and Electrons. Cambridge Univ. Press.

- 1939. Philosophy of Physical Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-7581-2054-0 (1938 Tarner lectures at Cambridge)

- 1946. Fundamental Theory. Cambridge University Press.

See also[edit]

Astronomy[edit]

- Chandrasekhar limit

- Eddington luminosity (also called the Eddington limit)

- Gravitational lens

- Outline of astronomy

- Stellar nucleosynthesis

- Timeline of stellar astronomy

- List of astronomers

Science[edit]

- Arrow of time

- Classical unified field theories

- Dimensionless physical constant

- Dirac large numbers hypothesis (also called the Eddington–Dirac number)

- Eddington number

- General relativity

- Introduction to quantum mechanics

- Luminiferous aether

- Parameterized post-Newtonian formalism

- Special relativity

- Theory of everything (also called "final theory" or "ultimate theory")

- Timeline of gravitational physics and relativity

- List of famous experiments

People[edit]

Organizations[edit]

- Quakers (also called the Religious Society of Friends)

- Royal Astronomical Society

- Trinity College, Cambridge

Other[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Arthur Eddington at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ Plummer, H. C. (1945). "Arthur Stanley Eddington. 1882–1944". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 5 (14): 113–126. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1945.0007. S2CID 121473352.

- ^ a b The Internal Constitution of the Stars A. S. Eddington The Scientific Monthly Vol. 11, No. 4 (Oct., 1920), pp. 297-303 JSTOR 6491

- ^ a b Eddington, A. S. (1916). "On the radiative equilibrium of the stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77: 16–35. Bibcode:1916MNRAS..77...16E. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.1.16.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- ^ a b c d e f Douglas, A. Vibert (1956). The Life of Arthur Eddington. Thomas Nelson and Sons. pp. 92–95.

- ^ "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ Padmanabhan, T. (2005). "The dark side of astronomy". Nature. 435 (7038): 20–21. Bibcode:2005Natur.435...20P. doi:10.1038/435020a.

- ^ a b c Chandrasekhar, Subrahmanyan (1983). Eddington: The most distinguished astrophysicist of his time. Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0521257466.

- ^ a b Dyson, F.W.; Eddington, A.S.; Davidson, C.R. (1920). "A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun's Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Solar eclipse of May 29, 1919". Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A. 220 (571–581): 291–333. Bibcode:1920RSPTA.220..291D. doi:10.1098/rsta.1920.0009.

- ^ Kennefick, Daniel (5 September 2007). "Not Only Because of Theory: Dyson, Eddington and the Competing Myths of the 1919 Eclipse Expedition". arXiv:0709.0685. Bibcode:2007arXiv0709.0685K. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2012.07.010. S2CID 119203172.

- ^ Kennefick, Daniel (1 March 2009). "Testing relativity from the 1919 eclipse—a question of bias". Physics Today. 62 (3): 37–42. Bibcode:2009PhT....62c..37K. doi:10.1063/1.3099578.

- ^ As related by Eddington to Chandrasekhar and quoted in Walter Isaacson "Einstein: His Life and Universe", page 262

- ^ Srinivasan, G. (2014). What are the stars?. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 31. ISBN 9783642453021.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Whittaker, Edmund (1945). "Eddington's Theory of the Constants of Nature". The Mathematical Gazette. 29 (286): 137–144. doi:10.2307/3609461. JSTOR 3609461.

- ^ Kean, Sam (2010). The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of the Elements. New York: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 9780316089081.

- ^ Barrow, J. D.; Tipler, F. J. (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-851949-2.

- ^ "Physics World – IOPscience". physicsworldarchive.iop.org.

- ^ "Eddington number". 16 March 2008.

- ^ Physics World (Institute of Physics) July 2012 page 15

- ^ a b de Koninck, Charles (2008). "The philosophy of Sir Arthur Eddington and The problem of indeterminism". The writings of Charles de Koninck. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 978-0-268-02595-3. OCLC 615199716.

- ^ Douglas, A. Vibert (1956). The Life of Arthur Eddington. Thomas Nelson and Sons. p. 44.

- ^ Gates, S. James; Pelletier, Cathie (2019). Proving Einstein Right: The Daring Expeditions that Changed How We Look at the Universe. Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1541762251.

- ^ Quakers and the Arts: "Plain and Fancy"- An Anglo-American Perspective, David Sox, Sessions Book Trust, 2000, p. 65

- ^ "Past Winners of the Catherine Wolfe Bruce Gold Medal". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Henry Draper Medal". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "A.S. Eddington (1882–1944)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Who's who entry for A.S. Eddington.

- ^ "TIME Magazine Cover: Sir Arthur Eddington – Apr. 16, 1934". TIME.com.

- ^ "Structural Realism": entry by James Ladyman in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Further reading[edit]

- Durham, Ian T., "Eddington & Uncertainty". Physics in Perspective (September – December). Arxiv, History of Physics.

- Kilmister, C. W. (1994). Eddington's search for a fundamental theory. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37165-0.

- Lecchini, Stefano, "How Dwarfs Became Giants. The Discovery of the Mass–Luminosity Relation{{-"}. Bern Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science, pp. 224 (2007).

- Vibert Douglas, A. (1956). The Life of Arthur Stanley Eddington. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd.

- Stanley, Matthew. "An Expedition to Heal the Wounds of War: The 1919 Eclipse Expedition and Eddington as Quaker Adventurer." Isis 94 (2003): 57–89.

- Stanley, Matthew. "So Simple a Thing as a Star: Jeans, Eddington, and the Growth of Astrophysical Phenomenology" in British Journal for the History of Science, 2007, 40: 53–82.

- Stanley, Matthew (2007). Practical Mystic: Religion, Science, and A.S. Eddington. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77097-0.

External links[edit]

- Works by Arthur Eddington at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Arthur Stanley Eddington at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Arthur Eddington at Internet Archive

- Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington at Find a Grave

- Trinity College Chapel

- Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882–1944). University of St Andrews, Scotland.

- Quotations by Arthur Eddington

- Arthur Stanley Eddington The Bruce Medalists.

- Russell, Henry Norris, "Review of The Internal Constitution of the Stars by A.S. Eddington". Ap.J. 67, 83 (1928).

- Experiments of Sobral and Príncipe repeated in the space project in proceeding in fórum astronomical.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Arthur Eddington", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Biography and bibliography of Bruce medalists: Arthur Stanley Eddington

- Links to online copies of important books by Eddington: 'The Nature of the Physical World', 'The Philosophy of Physical Science', 'Relativity Theory of Protons and Electrons', and 'Fundamental Theory'

- 1882 births

- 1944 deaths

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Alumni of the Victoria University of Manchester

- British anti–World War I activists

- British astrophysicists

- British conscientious objectors

- British pacifists

- Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925)

- Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- English Quakers

- English astronomers

- Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Fellows of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Knights Bachelor

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

- People from Kendal

- Presidents of the Physical Society

- Presidents of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Recipients of the Bruce Medal

- Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

- British relativity theorists

- Royal Medal winners

- Senior Wranglers

- 20th-century British scientists

Einstein had what might be called a night-sky theology, a sense of the awesomeness of the universe that even atheists and materialists feel.Photograph by Ernst Haas / Getty

Einstein had what might be called a night-sky theology, a sense of the awesomeness of the universe that even atheists and materialists feel.Photograph by Ernst Haas / Getty