Gospel of John - Wikipedia

Gospel of John

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

This article is about the book in the New Testament. For the film, see The Gospel of John (2003 film) and The Gospel of John (2014 film).

Not to be confused with Johannine epistles.

Books of the

New Testament

Gospels

Matthew

Mark

Luke

John

Acts

Acts of the Apostles

Epistles

Romans

1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians

Galatians · Ephesians

Philippians · Colossians

1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians

1 Timothy · 2 Timothy

Titus · Philemon

Hebrews · James

1 Peter · 2 Peter

1 John · 2 John · 3 John

Jude

Apocalypse

Revelation

New Testament manuscripts

v

t

e

Part of a series of articles on

John in the Bible

Johannine literature

Gospel

Epistles

First

Second

Third

Revelation

Events

Authorship

Apostle

Beloved disciple

Evangelist

Patmos

Presbyter

Related literature

Apocryphon

Acts

Signs Gospel

See also

Johannine Christianity

Logos

Holy Spirit in Johannine literature

John's vision of the Son of Man

New Testament people named John

v

t

e

The Gospel of John (Greek: Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, romanized: Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the canonical gospels.[1][Notes 1] The work is anonymous, although it identifies an unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved" as the source of its traditions.[2] It is closely related in style and content to the three Johannine epistles, and most scholars treat the four books, along with the Book of Revelation, as a single corpus of Johannine literature, albeit not from the same author.[3]

The discourses contained in this gospel seem to be concerned with issues of the church–synagogue debate at the time of composition.[4] It is notable that in John, the community appears to define itself primarily in contrast to Judaism, rather than as part of a wider Christian community.[Notes 2] Though Christianity started as a movement within Judaism, it gradually separated from Judaism because of mutual opposition between the two religions.[5]

Contents

1Composition and setting

1.1Johannine literature

1.2Genre

1.3Composition

1.4Sources

2Structure and content

3Theology

3.1Christology

3.2Logos

3.3Cross

3.4Sacraments

3.4.1Frequency of allusion

3.4.2Importance to the evangelist

3.5Individualism

3.6John the Baptist

3.7Gnosticism

4Comparison with other writings

4.1Material

4.2Theological emphasis

4.3Chronology

4.4Literary style

4.5Discrepancies

4.6Historical reliability

5Representations

6See also

7References

7.1Notes

7.2Footnotes

7.3Bibliography

8External links

Composition and setting[edit]

Further information: Authorship of the Johannine works

A Syriac Christian rendition of St. John the Evangelist, from the Rabbula Gospels.

Johannine literature[edit]

The Gospel of John, the three Johannine epistles, and the Book of Revelation, exhibit marked similarities, although more so between the gospel and the epistles (especially the gospel and 1 John) than between those and Revelation.[6] Most scholars therefore treat the five as a single corpus of Johannine literature, albeit not from the same author.[3]

Genre[edit]

John contains many characteristics of those writings belonging to the genre of Greco-Roman biography, a) internally; including establishing the origins and ancestry of the subject (John 1:1), a focus on the main subject's great words and deeds, a focus on the death of the subject and the subsequent consequences, b) externally; promotion of a particular hero (where non-biographical writings focus on the events surrounding the characters rather than the character himself), the domination of the use of verbs by the subject (in John, 55% of verbs are taken up by Jesus' deeds), the prominence of the final portion of the subject's life (one third of John's Gospel is taken up by the last week of Jesus' life, comparable to 26% of Tacitus's Agricola and 37% of Xenophon's Agesilaus), the reference to the main subject in the beginning of the text, etc.[7]

Composition[edit]

The gospel of John went through two to three stages, or "editions", before reaching its current form around AD 90–110.[8][9] It speaks of an unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved" as the source of its traditions, but does not say specifically that he is its author.[2] Christian tradition identifies this disciple as the apostle John, but for a variety of reasons the majority of scholars have abandoned this view or hold it only tenuously.[10][Notes 3]

Sources[edit]

The scholarly consensus in the second half of the 20th century was that John was independent of the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), but this agreement broke down in the last decade of the century and there are now many who believe that John did know some version of Mark and possibly Luke, as he shares with them some items of vocabulary and clusters of incidents arranged in the same order.[11][12] Key terms from the synoptics, however, are absent or nearly so, implying that if the author did know those gospels he felt free to write independently.[12]

Many incidents in John, such as the wedding in Cana, the encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well, and the raising of Lazarus are not paralleled in the synoptics, and most scholars believe he drew these from an independent source called the "signs gospel", and the speeches of Jesus from a second "discourse" source.[13][12] Most scholars agree that the prologue to John employs an early hymn.[14]

The gospel makes extensive use of the Jewish scriptures.[13] John quotes from them directly, references important figures from them, and uses narratives from them as the basis for several of the discourses. But the author was also familiar with non-Jewish sources: the Logos of the prologue (the Word that is with God from the beginning of creation) derives from both the Jewish concept of Lady Wisdom and from the Greek philosophers, while John 6 alludes not only to the exodus but also to Greco-Roman mystery cults, while John 4 alludes to Samaritan messianic beliefs.[15]

Structure and content[edit]

Jesus giving the Farewell Discourse to his 11 remaining disciples, from the Maestà of Duccio, 1308–1311.

Further information: Prologue to John, Book of Signs, and John 21

The majority of scholars see four sections in this gospel: a prologue (1:1–18); an account of the ministry, often called the "Book of Signs" (1:19–12:50); the account of Jesus' final night with his disciples and the passion and resurrection, sometimes called the "book of glory" (13:1–20:31); and an epilogue which did not form part of the original text (Chapter 21).[16][17]

The prologue informs readers of the true identity of Jesus: he is the Word of God through whom the world was created and who took on human form.[18] John 1:10–12 outlines the story to follow: Jesus came to the Jews and the Jews rejected him, but "to all who received him (the circle of Christian believers), who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God."[19]

Jesus is baptised, calls his disciples, and begins his earthly ministry.[20] He travels from place to place informing his hearers about God the Father, offering eternal life to all who will believe, and performing miracles which are signs of the authenticity of his teachings.[20][21] This creates tensions with the religious authorities (manifested as early as 5:17–18), who decide that he must be eliminated.[20]

Jesus prepares the disciples for their coming lives without his physical presence, and prays for them and for himself.[21] The scene is thus prepared for the narrative of his passion, death and resurrection. The section ends with a conclusion on the purpose of the gospel: "that [the reader] may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name."[22]

Chapter 21 tells of Jesus' post-resurrection appearance to his disciples in Galilee, the miraculous catch of fish, the prophecy of the crucifixion of Peter, the restoration of Peter, and the fate of the Beloved Disciple.[22]

The structure is highly schematic: there are seven "signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the resurrection of Jesus), and seven "I am" sayings and discourses, culminating in Thomas's proclamation of the risen Jesus as "my Lord and my God" (the same title, dominus et deus, claimed by the Emperor Domitian, an indication of the date of composition).[23]

Theology[edit]

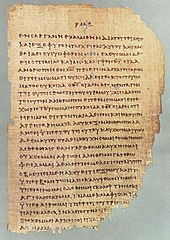

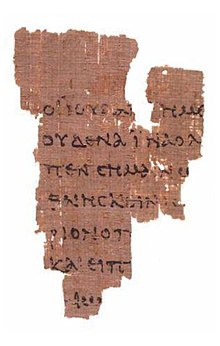

The Rylands Papyrus the oldest known New Testament fragment, dated from its handwriting to about 125.

Christology[edit]

Further information: Christology

John's "high Christology" depicts Jesus as divine, preexistent, and identified with the one God,[24] talking openly about his divine role and echoing Yahweh's "I Am that I Am" with seven "I Am" declarations of his own.[Notes 4]

Logos[edit]

Main article: Logos (Christianity)

In the prologue, John identifies Jesus as the Logos (Word). In Ancient Greek philosophy, the term logos meant the principle of cosmic reason. In this sense, it was similar to the Hebrew concept of Wisdom, God's companion and intimate helper in creation. The Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo merged these two themes when he described the Logos as God's creator of and mediator with the material world. The evangelist adapted Philo's description of the Logos, applying it to Jesus, the incarnation of the Logos.[25]

Cross[edit]

The portrayal of Jesus' death in John is unique among the four Gospels. It does not appear to rely on the kinds of atonement theology indicative of vicarious sacrifice (cf. Mark 10:45, Romans 3:25) but rather presents the death of Jesus as his glorification and return to the Father. Likewise, the three "passion predictions" of the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 8:31, 9:31, 10:33–34 and pars.) are replaced instead in John with three instances of Jesus explaining how he will be exalted or "lifted up"(John 3:14, 8:28, 12:32). The verb for "lifted up" reflects the double entendre at work in John's theology of the cross, for Jesus is both physically elevated from the earth at the crucifixion but also, at the same time, exalted and glorified.[26]

Sacraments[edit]

Further information: Sacrament

Among the most controversial areas of interpretation of John is its sacramental theology. Scholars' views have fallen along a wide spectrum ranging from anti-sacramental and non-sacramental, to sacramental, to ultra-sacramental and hyper-sacramental.[27] Scholars disagree both on whether and how frequently John refers to the sacraments at all, and on the degree of importance he places upon them. Individual scholars' answers to one of these questions do not always correspond to their answer to the other.[28]

Frequency of allusion[edit]

According to Rudolf Bultmann, there are three sacramental allusions: one to baptism (3:5), one to the Eucharist (6:51–58), and one to both (19:34). He believed these passages to be later interpolations, though most scholars now reject this assessment. Some scholars on the weaker-sacramental side of the spectrum deny that there are any sacramental allusions in these passages or in the gospel as a whole, while others see sacramental symbolism applied to other subjects in these and other passages. Oscar Cullmann and Bruce Vawter, a Protestant and a Catholic respectively, and both on the stronger-sacramental end of the spectrum, have found sacramental allusions in most chapters. Cullmann found references to baptism and the Eucharist throughout the gospel, and Vawter found additional references to matrimony in 2:1–11, anointing of the sick in 12:1–11, and penance in 20:22–23. Towards the center of the spectrum, Raymond Brown is more cautious than Cullmann and Vawter but more lenient than Bultmann and his school, identifying several passages as containing sacramental allusions and rating them according to his assessment of their degree of certainty.[28]

Importance to the evangelist[edit]

Most scholars on the stronger-sacramental end of the spectrum assess the sacraments as being of great importance to the evangelist. However, some scholars who find fewer sacramental references, such as Udo Schnelle, view the references that they find as highly important as well. Schnelle in particular views John's sacramentalism as a counter to Docetist anti-sacramentalism. On the other hand, though he agrees that there are anti-Docetic passages, James Dunn views the absence of a Eucharistic institution narrative as evidence for an anti-sacramentalism in John, meant to warn against a conception of eternal life as dependent on physical ritual.[28]

Individualism[edit]

In comparison to the synoptic gospels, the Fourth Gospel is markedly individualistic, in the sense that it places emphasis more on the individual's relation to Jesus than on the corporate nature of the Church.[28][29] This is largely accomplished through the consistently singular grammatical structure of various aphoristic sayings of Jesus throughout the gospel.[28][Notes 5] According to Richard Bauckham, emphasis on believers coming into a new group upon their conversion is conspicuously absent from John.[28] There is also a theme of "personal coinherence", that is, the intimate personal relationship between the believer and Jesus in which the believer "abides" in Jesus and Jesus in the believer.[29][28][Notes 6] According to C. F. D. Moule, the individualistic tendencies of the Fourth Gospel could potentially give rise to a realized eschatology achieved on the level of the individual believer; this realized eschatology is not, however, to replace "orthodox", futurist eschatological expectations, but is to be "only [their] correlative."[30] Some have argued that the Beloved Disciple is meant to be all followers of Jesus, inviting all into such a personal relationship with Christ. Beyond this, the emphasis on the individual's relationship with Jesus in the Gospel has suggested its usefulness for contemplation on the life of Christ.[31]

John the Baptist[edit]

Further information: John the Baptist

John's account of the Baptist is different from that of the synoptic gospels. In this gospel, John is not called "the Baptist."[32] The Baptist's ministry overlaps with that of Jesus; his baptism of Jesus is not explicitly mentioned, but his witness to Jesus is unambiguous.[32] The evangelist almost certainly knew the story of John's baptism of Jesus and he makes a vital theological use of it.[33] He subordinates the Baptist to Jesus, perhaps in response to members of the Baptist's sect who regarded the Jesus movement as an offshoot of their movement.[34]

In John's gospel, Jesus and his disciples go to Judea early in Jesus' ministry before John the Baptist was imprisoned and executed by Herod. He leads a ministry of baptism larger than John's own. The Jesus Seminar rated this account as black, containing no historically accurate information.[35] According to the biblical historians at the Jesus Seminar, John likely had a larger presence in the public mind than Jesus.[36]

Gnosticism[edit]

Further information: Christian Gnosticism

In the first half of the 20th century, many scholars, primarily including Rudolph Bultmann, have forcefully argued that the Gospel of John has elements in common with Gnosticism.[34] Christian Gnosticism did not fully develop until the mid-2nd century, and so 2nd-century Proto-Orthodox Christians concentrated much effort in examining and refuting it.[37] To say John's gospel contained elements of Gnosticism is to assume that Gnosticism had developed to a level that required the author to respond to it.[38] Bultmann, for example, argued that the opening theme of the Gospel of John, the pre-existing Logos, along with John's duality of light versus darkness in his Gospel were originally Gnostic themes that John adopted. Other scholars, e.g. Raymond E. Brown have argued that the pre-existing Logos theme arises from the more ancient Jewish writings in the eighth chapter of the Book of Proverbs, and was fully developed as a theme in Hellenistic Judaism by Philo Judaeus.[39] The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran verified the Jewish nature of these concepts.[40] April DeConick has suggested reading John 8:56 in support of a Gnostic theology,[41] however recent scholarship has cast doubt on her reading.[42]

Gnostics read John but interpreted it differently from the way non-Gnostics did.[43] Gnosticism taught that salvation came from gnosis, secret knowledge, and Gnostics did not see Jesus as a savior but a revealer of knowledge.[44] Barnabas Lindars asserts that the gospel teaches that salvation can only be achieved through revealed wisdom, specifically belief in (literally belief into) Jesus.[45]

Raymond Brown contends that "The Johannine picture of a savior who came from an alien world above, who said that neither he nor those who accepted him were of this world,[46] and who promised to return to take them to a heavenly dwelling[47] could be fitted into the gnostic world picture (even if God's love for the world in 3:16 could not)."[48] It has been suggested that similarities between John's gospel and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish Apocalyptic literature.[49]

Comparison with other writings[edit]

The Gospel of John is significantly different from the synoptic gospels, with major variations in material, theological emphasis, chronology, and literary style.[50] There are also some discrepancies between John and the Synoptics, some amounting to contradictions.[50] The gospel forms the core of an emerging canon of Johannine works, the Johannine corpus, consisting of the gospel, the three Johannine letters, and the Apocalypse, all coming from the same theological background and opposed to the "Petrine corpus."

Material[edit]

John lacks scenes from the Synoptics such as Jesus' baptism,[51] the calling of the Twelve, exorcisms, parables, and the Transfiguration. Conversely, it includes scenes not found in the Synoptics, including Jesus turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana, the resurrection of Lazarus, Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, and multiple visits to Jerusalem.[50]

In the fourth gospel, Jesus' mother Mary, while frequently mentioned, is never identified by name.[52][53] John does assert that Jesus was known as the "son of Joseph" in 6:42. For John, Jesus' town of origin is irrelevant, for he comes from beyond this world, from God the Father.[54]

While John makes no direct mention of Jesus' baptism,[51][50] he does quote John the Baptist's description of the descent of the Holy Spirit as a dove, as happens at Jesus' baptism in the Synoptics. Major synoptic speeches of Jesus are absent, including the Sermon on the Mount and the Olivet Discourse,[55] and the exorcisms of demons are never mentioned as in the Synoptics.[51][56] John never lists all of the Twelve Disciples and names at least one disciple, Nathanael, whose name is not found in the Synoptics. Thomas is given a personality beyond a mere name, described as "Doubting Thomas".[57]

Theological emphasis[edit]

Jesus is identified with the Word ("Logos"), and the Word is identified with theos ("god" in Greek);[58] no such identification is made in the Synoptics.[59] In Mark, Jesus urges his disciples to keep his divinity secret, but in John he is very open in discussing it, even referring to himself as "I AM", the title God gives himself in Exodus at his self-revelation to Moses. In the Synoptics, the chief theme is the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Heaven (the latter specifically in Matthew), while John's theme is Jesus as the source of eternal life and the Kingdom is only mentioned twice.[50][56] In contrast to the synoptic expectation of the Kingdom (using the term parousia, meaning "coming"), John presents a more individualistic, realized eschatology.[60][61][Notes 7]

Chronology[edit]

In the Synoptics, the ministry of Jesus takes a single year, but in John it takes three, as evidenced by references to three Passovers. Events are not all in the same order: the date of the crucifixion is different, as is the time of Jesus' anointing in Bethany and the cleansing of the temple occurs in the beginning of Jesus' ministry rather than near its end.[50]

Literary style[edit]

In the Synoptics, quotations from Jesus are usually in the form of short, pithy sayings; in John, longer quotations are often given. The vocabulary is also different, and filled with theological import: in John, Jesus does not work "miracles" (Greek: δῠνάμεις, romanized: dynámeis, sing. δύνᾰμῐς, dýnamis), but "signs" (Greek: σημεῖᾰ, romanized: sēmeia, sing. σημεῖον, sēmeion) which unveil his divine identity.[50] Most scholars consider John not to contain any parables.[63] Rather it contains metaphorical stories or allegories, such as those of the Good Shepherd and of the True Vine, in which each individual element corresponds to a specific person, group, or thing. Other scholars consider stories like the childbearing woman (16:21) or the dying grain (12:24) to be parables.[Notes 8]

Discrepancies[edit]

According to the Synoptics, the arrest of Jesus was a reaction to the cleansing of the temple, while according to John it was triggered by the raising of Lazarus.[50] The Pharisees, portrayed as more uniformly legalistic and opposed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels, are instead portrayed as sharply divided; they debate frequently in John's accounts. Some, such as Nicodemus, even go so far as to be at least partially sympathetic to Jesus. This is believed to be a more accurate historical depiction of the Pharisees, who made debate one of the tenets of their system of belief.[64]

Historical reliability[edit]

Further information: Historicity of the Bible

The teachings of Jesus found in the synoptic gospels are very different from those recorded in John, and since the 19th century scholars have almost unanimously accepted that these Johannine discourses are less likely than the synoptic parables to be historical, and were likely written for theological purposes.[65] By the same token, scholars usually agree that John is not entirely without historical value: certain sayings in John are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts, his representation of the topography around Jerusalem is often superior to that of the synoptics, his testimony that Jesus was executed before, rather than on, Passover, might well be more accurate, and his presentation of Jesus in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are possibly more historically plausible than their synoptic parallels.[66]

Representations[edit]

Bede translating the Gospel of John on his deathbed, by James Doyle Penrose, 1902.

The gospel has been depicted in live narrations and dramatized in productions, skits, plays, and Passion Plays, as well as in film. The most recent such portrayal is the 2014 film The Gospel of John, directed by David Batty and narrated by David Harewood and Brian Cox, with Selva Rasalingam as Jesus. The 2003 film The Gospel of John, was directed by Philip Saville, narrated by Christopher Plummer, with Henry Ian Cusick as Jesus.

Parts of the gospel have been set to music. One such setting is Steve Warner's power anthem "Come and See", written for the 20th anniversary of the Alliance for Catholic Education and including lyrical fragments taken from the Book of Signs. Additionally, some composers have made settings of the Passion as portrayed in the gospel, most notably the one composed by Johann Sebastian Bach, although some verses are borrowed from Matthew.

See also[edit]

Authorship of the Johannine works

Chronology of Jesus

Free Grace theology

Gospel harmony

Last Gospel

Egerton Gospel

List of Bible verses not included in modern translations

List of Gospels

Textual variants in the Gospel of John

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

^ Also called the Gospel of John, the Fourth Gospel, or simply John.

^ Chilton & Neusner 2006, p. 5: "by their own word what they (the writers of the New Testament) set forth in the New Testament must qualify as a Judaism. ... [T]o distinguish between the religious world of the New Testament and an alien Judaism denies the authors of the New Testament books their most fiercely held claim and renders incomprehensible much of what they said."

^ For the circumstances which led to the formation of the tradition, and the reasons why the majority of modern scholars reject it, see Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, pp. 41–42

^ [25]

"I am the bread of life"[6:35]

"I am the light of the world"[8:12]

"I am the gate for the sheep"[10:7]

"I am the good shepherd"[10:11]

"I am the resurrection and the life"[11:25]

"I am the way and the truth and the life"[14:6]

"I am the true vine"[15:1]

^ Bauckham (2015) contrasts John's consistent use of the third person singular ("The one who ..."; "If anyone ..."; "Everyone who ..."; "Whoever ..."; "No one ...") with the alternative third person plural constructions he could have used instead ("Those who ..."; ""All those who ..."; etc.). He also notes that the sole exception occurs in the prologue, serving a narrative purpose, whereas the later aphorisms serve a "paraenetic function".

^ See John 6:56, 10:14–15, 10:38, and 14:10, 17, 20, and 23.

^ Realized eschatology is a Christian eschatological theory popularized by C. H. Dodd (1884–1973). It holds that the eschatological passages in the New Testament do not refer to future events, but instead to the ministry of Jesus and his lasting legacy.[62] In other words, it holds that Christian eschatological expectations have already been realized or fulfilled.

^ See Zimmermann 2015, pp. 333–60.

Footnotes[edit]

^ Burkett 2002, p. 215.

^ Jump up to:a b Burkett 2002, p. 214.

^ Jump up to:a b Harris 2006, p. 479.

^ Lindars 1990, p. 53.

^ Lindars 1990, p. 59.

^ Van der Watt 2008, p. 1.

^ Kostenberger, Andreas "The Genre of the Fourth Gospel and Greco-Roman Literary Conventions," in Porter, Stanley E., and Andrew W. Pitts, eds. Christian Origins and Greco-Roman Culture: Social and Literary Contexts for the New Testament. Vol. 1. Brill, 2012, 445–463, esp. 449.

^ Edwards 2015, p. ix.

^ Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

^ Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, p. 41.

^ Lincoln 2005, pp. 29–30.

^ Jump up to:a b c Fredriksen 2008, p. unpaginated.

^ Jump up to:a b Reinhartz 2011, p. 168.

^ Perkins 1993, p. 109.

^ Reinhartz 2011, p. 171. See also: Jonathan Bourgel, " John 4:4–42: Defining A Modus Vivendi Between Jews And The Samaritans", Journal of Theological Studies 69 (2018), pp. 39–65 (https://www.academia.edu/37029909/Bourgel_-_JTS_-_John_4_4-42_The_terms_of_a_modus_vivendi_between_Jews_and_the_Samaritans)..

^ Moloney 1998, p. 23.

^ Bauckham 2007, p. 271.

^ Aune 2003, p. 245.

^ Aune 2003, p. 246.

^ Jump up to:a b c Van der Watt 2008, p. 10.

^ Jump up to:a b Kruse 2004, p. 17.

^ Jump up to:a b Edwards 2015, p. 171.

^ Witherington 2004, p. 83.

^ Hurtado 2005, p. 51.

^ Jump up to:a b Harris 2006, pp. 302–10.

^ Robert Kysar, "John: The Maverick Gospel" (Louisville: Westminster John Knox), 1976, pp. 49–54

^ Hans Boersma, Matthew Levering, eds. (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Sacramental Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780191634185.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Bauckham 2015.

^ Jump up to:a b Moule 1962, p. 172.

^ Moule 1962, p. 174.

^ Shea, SJ, Henry J. (Summer 2017). "The Beloved Disciple and the Spiritual Exercises". Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits. 49 (2).

^ Jump up to:a b Cross & Livingstone 2005.

^ Barrett 1978, p. 16.

^ Jump up to:a b Harris 2006.

^ Funk & Jesus Seminar 1998, pp. 365–440.

^ Funk & Jesus Seminar 1998, p. 268.

^ Olson 1999, p. 36.

^ Kysar 2005, pp. 88ff.

^ Brown 1997.

^ Charlesworth, James H. "The Historical Jesus in the Fourth Gospel: A Paradigm Shift?." Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 8.1 (2010): 42

^ DeConick, April D. "Who is Hiding in the Gospel of John? Reconceptualizing Johannine Theology and the Roots of Gnosticism." in Histories of the Hidden God: Concealment and Revelation in Western Gnostic, Esoteric, and Mystical Traditions. (2013) 13–29.

^ Llewelyn, Stephen Robert, Alexandra Robinson, and Blake Edward Wassell. "Does John 8:44 Imply That the Devil Has a Father?: Contesting the Pro-Gnostic Reading." Novum Testamentum 60.1 (2018): 14–23.

^ Most 2005, pp. 121ff.

^ Skarsaune 2008, pp. 247ff.

^ Lindars 1990, p. 62.

^ John 17:14

^ John 14:2–3

^ Brown 1997, p. 375.

^ Kovacs 1995.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Burge 2014, pp. 236–37.

^ Jump up to:a b c Funk, Hoover & Jesus Seminar 1993, pp. 1–30.

^ Williamson 2004, p. 265.

^ Michaels 1971, p. 733.

^ Fredriksen 2008.

^ Pagels 2003.

^ Jump up to:a b Thompson 2006, p. 184.

^ Walvoord, John F. (1985). The Bible Knowledge Commentary. Wheaton, IL: Victor Books. p. 313.

^ Ehrman 2005.

^ Carson, D. A. (1991). The Pillar New Testament Commentary: The Gospel According to John. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eardmans Publishing Co. p. 117.

^ Moule 1962, pp. 172–74.

^ Sander 2015.

^ Ladd & Hagner 1993, p. 56.

^ Barry 1911.

^ Neusner 2003, p. 8.

^ Sanders 1995, pp. 57, 70–71.

^ Theissen & Merz 1998, pp. 36–37.

Bibliography[edit]

Aune, David E. (2003). "John, Gospel of". The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-21917-8.

Barrett, C. K. (1978). The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22180-5.

Bauckham, Richard (2007). The Testimony of the Beloved Disciple: Narrative, History, and Theology in the Gospel of John. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-3485-5.

—— (2015). Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4412-2708-9.

Blomberg, Craig (2011). The Historical Reliability of John's Gospel. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 0-8308-3871-6.

Bourgel, Jonathan (2018). "John 4 : 4–42: Defining A Modus Vivendi Between Jews And The Samaritans". Journal of Theological Studies. 69 (1): 39–65.

Brown, Raymond E. (1966). The Gospel According to John, Volume 1. Anchor Bible series. 29. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-01517-2.

Brown, Raymond E. (1997). An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

Burge, Gary M. (2014). "Gospel of John". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-72224-3.

Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

Carson, D. A.; Moo, Douglas J. (2009). An Introduction to the New Testament. HarperCollins Christian Publishing. ISBN 978-0-310-53955-1.

Chilton, Bruce; Neusner, Jacob (2006). Judaism in the New Testament: Practices and Beliefs. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-81497-8.

Combs, William W. (1987). "Nag Hammadi, Gnosticism and New Testament Interpretation". Grace Theological Journal. 8 (2): 195–212.

Culpepper, R. Alan (2011). The Gospel and Letters of John. Abingdon Press.

Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). "John, Gospel of St.". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

Denaux, Adelbert (1992). "The Q-Logion Mt 11, 27 / Lk 10, 22 and the Gospel of John". In Denaux, Adelbert (ed.). John and the Synoptics. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium. 101. Leuven University Press. pp. 113–47. ISBN 978-90-6186-498-1.

Dunn, James D. G., ed. (1992). Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways – A.D. 70 to 135. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

Alexander, Philip S. (1992). 'The Parting of the Ways' from the Perspective of Rabbinic Judaism. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

Dunn, James D. G. (1992). The Question of Anti-Semitism in the New Testament Writings of the Period. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

Edwards, Ruth B. (2015). Discovering John: Content, Interpretation, Reception. Discovering Biblical Texts. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7240-1.

Ehrman, Bart D. (1996). The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974628-6.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2009). Jesus, Interrupted. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-117393-6.

Fredriksen, Paula (2008). From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16410-7.

Harris, Stephen L. (2006). Understanding the Bible (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-296548-3.

Hendricks, Obrey M., Jr. (2007). "The Gospel According to John". In Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Carol A.; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible(3rd ed.). Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59856-032-9.

Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God?: Historical Questions about Earliest Devotion to Jesus. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2861-3.

Kostenberger, Andreas J. (2015). A Theology of John's Gospel and Letters: The Word, the Christ, the Son of God. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-52326-0.

Kovacs, Judith L. (1995). "Now Shall the Ruler of This World Be Driven Out: Jesus' Death as Cosmic Battle in John 12:20–36". Journal of Biblical Literature. 114 (2): 227–47. doi:10.2307/3266937. JSTOR 3266937.

Kysar, Robert (2005). Voyages with John: Charting the Fourth Gospel. Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-932792-43-0.

Kysar, Robert (2007). "The Dehistoricizing of the Gospel of John". In Anderson, Paul N.; Just, Felix; Thatcher, Tom (eds.). John, Jesus, and History, Volume 1: Critical Appraisals of Critical Views. Society of Biblical Literature Symposium series. 44. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-293-0.

Ladd, George Eldon; Hagner, Donald Alfred (1993). A Theology of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-0680-5.

Lincoln, Andrew (2005). Gospel According to St John: Black's New Testament Commentaries. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8822-9.

Lindars, Barnabas (1990). John. New Testament Guides. 4. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85075-255-4.

Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John M. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-081-4.

Martin, Dale B. (2012). New Testament History and Literature. Yale University Press.

Metzger, B. M.; Ehrman, B. D. (1985). The Text of New Testament. Рипол Классик. ISBN 978-5-88500-901-0.

Michaels, J. Ramsey (1971). "Verification of Jesus' Self-Revelation in His passion and Resurrection (18:1–21:25)". The Gospel of John. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4674-2330-4.

Moloney, Francis J. (1998). The Gospel of John. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5806-2.

Most, Glenn W. (2005). Doubting Thomas. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01914-0.

Moule, C. F. D. (July 1962). "The Individualism of the Fourth Gospel". Novum Testamentum. 5(2/3): 171–90. doi:10.2307/1560025. JSTOR 1560025.

Neusner, Jacob (2003). Invitation to the Talmud: A Teaching Book. South Florida Studies in the History of Judaism. 169. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-155-6.

Olson, Roger E. (1999). The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1505-0.

Perkins, Pheme (1993). Gnosticism and the New Testament. Fortress Press.

Pagels, Elaine H. (2003). Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50156-8.

Porter, Stanley E. (2015). John, His Gospel, and Jesus: In Pursuit of the Johannine Voice. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7170-1.

Van den Broek, Roelof; Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef (1981). Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain. 91. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-06376-1.

Reinhartz, Adele (2017). "The Gospel According to John". In Levine, Amy-Jill; Brettler, Marc Z. (eds.). The Jewish Annotated New Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-046185-0.

Sanders, E. P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.

Senior, Donald (1991). The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of John. Passion of Jesus Series. 4. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5462-0.

Skarsaune, Oskar (2008). In the Shadow of the Temple: Jewish Influences on Early Christianity. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2670-4.

Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998) [1996]. The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0863-8.

Thompson, Marianne Maye (2006). "The Gospel According to John". In Barton, Stephen C. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80766-1.

Tuckett, Christopher M. (2003). "Introduction to the Gospels". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

Van der Watt, Jan (2008). An Introduction to the Johannine Gospel and Letters. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-52174-3.

Williamson, Lamar, Jr. (2004). Preaching the Gospel of John: Proclaiming the Living Word. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22533-9.

Witherington, Ben (2004). The New Testament Story. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2765-4.

Zimmermann, Ruben (2015). Puzzling the Parables of Jesus: Methods and Interpretation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-6532-7.

External links[edit]

Online translations of the Gospel of John:

Over 200 versions in over 70 languages at Bible Gateway

The Unbound Bible from Biola University

David Robert Palmer, Translation from the Greek

Text of the Gospel with textual variants

The Egerton Gospel text; compare with Gospel of John