Steven Pinker: ‘The way to deal with pollution is not to rail against consumption’ | Science | The Guardian

The Observer

Steven Pinker

Steven Pinker: ‘The way to deal with pollution is not to rail against consumption’

The feather-ruffling Harvard psychologist’s new book, a defence of Enlightenment values, may be his most controversial yet

• Read an extract from Enlightenment Now here

Andrew Anthony

Sun 11 Feb 2018 19.00 AEDTLast modified on Thu 22 Mar 2018 10.48 AEDT

Shares

4,051

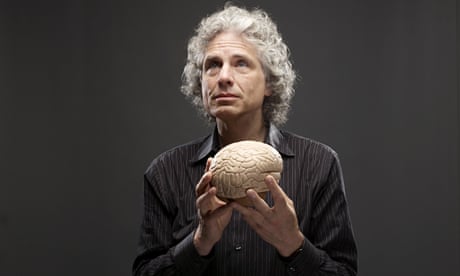

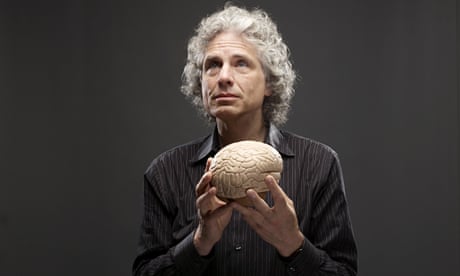

Comments819 Steven Pinker: ‘If scientific beliefs are just mythology, how come we can get to the moon?’ Photograph: Scott Nobles

Steven Pinker: ‘If scientific beliefs are just mythology, how come we can get to the moon?’ Photograph: Scott Nobles

Say the word “enlightenment” and it tends to conjure images of a certain kind of new-age spiritual “self-improvement”: meditation, candles, chakra lines. Add the definite article and a capital letter and the Enlightenment becomes something quite different: dead white men in wigs.

For many people, particularly in the west, reaching a state of mindful nirvana probably seems more relevant to their wellbeing than the writings of, say, Immanuel Kant and Adam Smith. But according to Enlightenment Now, a new book by the celebrated Harvard cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker, this is precisely where we’re getting our priorities wrong.

For Pinker, the Enlightenment is not some distant era, of interest only to historians and philosophers, but instead the foundation for all the many benefits and advantages to which we scarcely give a second’s thought in the 21st century.

Advertisement

He lists some of the advancements made by modern societies: “Newborns who will live more than eight decades, markets overflowing with food, clean water that appears with a flick of a finger and waste that disappears with another, pills that erase a painful infection, sons who are not sent off to war, daughters who can walk the streets in safety, critics of the powerful who are not jailed or shot, the world’s knowledge and culture available in a shirt pocket.”

These were not inevitable developments, Pinker wants us to know, but the fruits of the methods and values that were first popularised in the 18th century.

It’s safe to say that few of us stop and marvel at the extraordinary progress that humankind has made in the past couple of hundred years – a mere blink of the eye in evolutionary terms. Instead we’re more likely to lament the state of the world, deplore the ravenous nature of humanity, rage at the political and financial elites and despair at the empty materialism of consumer society.

What we do to combat poverty: that’s far more important than reducing inequality

But for Pinker, that’s an indulgence we can no longer afford. His book is a sustained, data-packed argument in favour of the principles promoted by the Enlightenment, “The Case,” as its subtitle puts it, “for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress.”

By virtue of science, I’m able to see and speak to Pinker via Skype, from my office in north London, while he is in his office in Boston. He explores the issue of inequality in some depth in the book, so it’s not an entirely trivial observation to note that his office looks to be about eight times larger than mine. But more on the distribution of wealth later.

Advertisement

Pinker’s trademark mop of silver curls, more like that of an ageing hard rock guitarist than an Ivy League academic, a pair of twinkling blue eyes and a ready expression of amusement beam out from my screen.

So, I ask, why do the values of the Enlightenment require such staunch and detailed defence (the book is more than 550 pages long, filled with graphs, footnotes and an exhaustive wealth of references) at this particular juncture in time?

“Among other things,” he replies, “they are under threat from authoritarian populism, religious fundamentalism and radicalism of the left and right. The great successes the world has enjoyed over the past decades and centuries are taken for granted, because many of the ideas responsible for them have become part of the establishment and no one is willing to defend them. So anything that is going right is not associated with any movement, any values, and that has left a vacuum that forces of extremism have rushed into.”

On my radar: Steven Pinker’s cultural highlights

Read more

Pinker, however, is willing to defend these established, even establishment, ideas. He is, rather bravely, prepared to be the bearer of good news. I say bravely because it’s not a popular stance. Announce that the world has gone badly wrong, that there are too many people, the Earth has been despoiled, we’ve never been in greater danger of death and destruction, or more adrift in the spiritual void of materialism and you’ll have the nodding attention of the news media and the intellectual classes.

But painstakingly show that, actually, things are on the whole quite a bit better than they have ever been and you’ll meet a torrent of bafflement and denial. Pinker knows this because he’s already been through the process with his previous book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, which persuasively argued – again with graphs and a mountain of research – that humankind was becoming progressively less violent.

It was a message that seemed to run counter to everything we thought we knew or had been told. How, after two world wars, the advent of the nuclear bomb, the proliferation of the arms industry and the brutality and murder we saw on television each night, could we seriously entertain the notion that we are becoming less violent?

But we are, and Pinker showed it with such an abundance of apparently irrefutable data that his detractors were left scrambling to redefine the meaning of violence.

“One of the surprises in presenting data on violence,” he says, “was the lengths to which people would go to deny it. When I presented graphs showing that rates of homicide had fallen by a factor of 50, that rates of death in war had fallen by a factor of more than 20, and rape and domestic violence and child abuse had all fallen, rather than rejoice, many audiences seemed to get increasingly upset. They racked their brains for ways in which things could not possibly be as good as the data suggested, including the entire category of questions that I regularly get: Isn’t X a form of violence? Isn’t advertising a form of violence? Isn’t plastic surgery a form of violence? Isn’t obesity a form of violence?”

Graphic evidence: Steven Pinker's optimism on trial

Read more

Advertisement

This time round, Pinker appears to have written with his doubting audience more firmly in mind. It’s as if he’s thought up every counter-argument before it can be made, and met each one with statistical refutations. It makes for a chewy but, well, enlightening read.

The idea for the book came out of a debate that Pinker had with the cultural critic Leon Wieseltier in the pages of the New Republic back in 2013. Wieseltier accused Pinker of invading the humanities with “scientism” – belief in the all-conquering value of science. Pinker replied that there was a false distinction between the humanities and science, that both were once the domain of educated thinkers, and that they were complementary in reaching a better understanding of the world and our place in it.

The debate, as they say, went viral, and Pinker was soon signing a book contract.

“But,” says Pinker, “ I quickly realised that a spat between a couple of magazine intellectuals was not worthy of a book-length treatment. So I submerged that particular debate in a larger defence of Enlightenment values, of which science is a part.”

The Enlightenment is a period placed by historians largely in the 18th century, and it remains a subject of much scholarly dispute about what it constituted and who were members of it. Even at the time, its adherents wrestled with definitions. In his 1784 essay An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?, Kant said that it amounted to “humankind’s emergence from its self-incurred immaturity”. He exhorted his readers to “dare to understand”.

Sign up for Bookmarks: discover new books in our weekly email

Read more

In Pinker’s conception, although the Enlightenment featured many different creeds, there was a unifying rejection of the constraints of religious faith and tribal loyalties, and in their place a belief in human universalism, the power of reason and the progressive role of science. For him it’s no coincidence that slavery and cruel punishments (such as being hanged, drawn and quartered) were outlawed in the wake of the Enlightenment. Nor that health, wealth and life expectancy began to rapidly improve.

Right from its inception, the Enlightenment had to do battle with the counter-Enlightenment – formed from the massed ranks of traditionalists, the religiously orthodox, and Romantics who recoiled from the unblinking gaze with which the Enlightenment thinkers felt emboldened to observe the world.

The struggle has continued ever since, with the Enlightenment being blamed for racism, imperialism and Nazi eugenics by critics from the left, and by the right for the moral void of atheism and materialism that found its murderous apogee in the Soviet Union and communist China. More recently, postmodernists have looked upon the Enlightenment as yet another false grand narrative, in which humanism, science and reason are just more belief systems, no more nor less valid than any others.

Advertisement

Pinker rejects all three positions. Far from sanctioning racism or nazism, he says, the Enlightenment laid the philosophical groundwork for universalism, the belief in equal rights for all, which ultimately triumphed over fascism and imperialism. Pinker argues that the inspiration for Nazi ideology should be more appropriately traced to Friedrich Nietzsche, who attacked the Enlightenment’s dependence on reason and argued for a “will to power” and the idea of “übermensch”, or superman. Nietzsche’s supporters won’t take that lying down.

And Marxism, he maintains, was not a legacy of the Enlightenment, but instead a pseudoscience that has more to do with German Romanticism. We can also expect Marxists to revolt.

As for postmodernism, Pinker is scathing.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Steven Pinker in 1994, the year he published The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. Photograph: Boston Globe/Getty Images

“If scientific beliefs are just a particular culture’s mythology, how come we can cure smallpox and get to the moon, and traditional cultures can’t? And if truth is just socially constructed, would you say that climate change is a myth? It’s the same with moral values. If moral values are nothing but cultural customs, would you agree that our disapproval of slavery or racial discrimination or the oppression of women is just a western fancy?”

Advertisement

No doubt Pinker will be admonished for mischaracterising the views of his opponents. But while there are certainly some polemical flourishes, Enlightenment Now is a careful and deeply researched piece of work. That is more than can be said of the accusations directed at him by some of his critics. A few weeks ago the biologist and blogger PZ Myers launched an attack on Pinker by putting out an edited clip of the Harvard professor in a public debate. The edited version seemed to suggest Pinker’s approval of supporters of the “alt-right”.

In fact, as the New York Times was quick to note, the unedited video showed Pinker was denouncing far-right ideas, and arguing that the left needs to make better arguments against them. It was a vivid example of how easy it can be, in the age of fake news and social media, to tarnish reputations with doctored evidence.

There have been several examples in recent years in which careers, including those of academics, have been brought to an ignominious end after social media campaigns based on disputed testimonies. Does this overheated climate of denunciation make Pinker more inhibited with his opinions?

“In my case, no,” he says. “But I think in the broader community that is a real danger. I think I have the reputation and the social capital to withstand distortions like that, but for younger and less established people, they might think twice about saying something that could be taken out of context, doctored, and go viral. So I do think it has a pernicious effect on the quality of intellectual discourse.”

Canadian-born, Pinker has done the faculty rounds of MIT, Stanford and Harvard, where he has built a formidable reputation as a multidisciplined thinker. But it is his books that have elevated him to the coveted position of public intellectual.

He wrote a series of well-received books about linguistics and psychology before publishing The Blank Slate in 2002, which argued that human behaviour was not simply or even largely a matter of environmental influence but instead shaped mostly by evolutionary adaptations. The book had its critics, but it became a bestseller. Ever since, Pinker’s audience has only grown in number – as have his critics.

It’s likely that Enlightenment Now will prove his most controversial book to date. His targets are many and he pulls few punches. For example, he takes the green movement to task for a “misanthropic environmentalism” that views modern humans as “vile despoilers of a pristine planet”.

Underpinning the belief that humans are destroying the Earth is the assumption that progress is not sustainable. Pinker disagrees, or at least argues that such doomsday conclusions have a long and fallible history. A fundamental tenet of the Enlightenment was that all problems, if studied long and hard enough, could be understood, and therefore at some point solved. And environmental problems, writes Pinker, are no exception.

Advertisement

He argues that progress is not only sustainable, but essential for attaining the knowledge that will enable us to find the cleanest and most efficient use of energy. In other words, scientific progress is what will make economic progress work. The book is a kind of rallying call to replace moral posturing with clear-eyed realism. Pinker’s message is that if we are not going to return to hunter-gathering – and we’re not – we had better face up to the task at hand.

That probably means using more nuclear reactors in the immediate future, something that, as with GM crops and shale gas, the green movement has responded to with apocalyptic protestations. And we may also have to acknowledge that to cut down on carbon emissions, the developing world first needs to attain a level of material wealth, by burning more energy, at which point it can turn its attention to the environment.

But perhaps he will be most in need of a tin hat for his unapologetic dismissal of the kind of anti-capitalists who see globalism as an international conspiracy bent on impoverishing the world for the enrichment of a tiny elite. A rave review by Microsoft founder Bill Gates, who called Enlightenment Now “My new favourite book of all time” (his previous favourite was The Better Angels of Our Nature), is unlikely to improve Pinker’s credentials in radical circles. Although he emphasises the need for strict regulation of capitalism, Pinker points to the data that shows that history has never seen such a massive movement out of poverty as that witnessed by the late 20th-century capitalist revolutions in China and India. It’s for this reason that he believes the dangers of inequality have been overstated.

Play Video

Play

Current Time0:00

/

Duration Time0:00

Loaded: 0%

Progress: 0%Fullscreen

Mute

FacebookTwitterPinterest Violence in retreat: Steven Pinker reveals the better angels of our nature.

“If wealth consisted of a finite pot that was divided in a zero-sum fashion,” he says, “then maybe poverty and inequality would be the same issue. But we know that isn’t true, that prosperity has increased maybe a hundred-fold since the Industrial Revolution. A second point that gets omitted from discussions on inequality: although it’s true that inequality within many rich western countries, especially the Anglosphere, UK, US and Canada, has grown, globally, inequality has fallen because the poor are getting richer faster than the rich are getting richer. China and India and Africa and Latin America are getting richer and that has reduced the global indices of poverty.”

Advertisement

Pinker accepts that, to a degree, the decreased inequality between the developing world and the west has come at the expense of increased inequality within the west, as manufacturing jobs that once benefited the lower middle class in America and Europe now benefit the lower middle class in China and India.

“If we were to step back and look at the progress of the world’s poor, we’d have to say this is a marvellous development. If you’re a British or American politician, of course it’s much harder to make that argument. More generally, the political issue that should engage us is how well off the people at the bottom of the ladder are. What we do to combat poverty: that’s far more important than reducing inequality.”

But what of the argument that this ever-expanding cycle of production and commercialisation is turning us into mindless consumers, who can only see value in disposable commodities?

Pinker laughs. “The intellectual and cultural critics who make that argument never seem to include trips to the continent or fine food and wine as a sign of soulless materialistic consumption. It’s always consumption by the other guy that they think of as morally compromising. There’s an issue with the effects on the environment: it really is not good to pollute the environment, particularly when it comes to carbon emissions, but the way to deal with that is not to rail against consumption. There are a lot of aspects of consumption, like being able to travel, see the world, be warm in the winter, cool in the summer, that are human goods. The challenge is: how do we get the most human benefit with the least environmental damage?”

Even Pinker’s fiercest enemies would acknowledge that, however it may have been distributed, there has been scientific and material progress since the advent of the Enlightenment. But many, perhaps most notably the philosopher John Gray, argue that it has not been – and cannot be – accompanied by moral progress.

Pinker disagrees. He thinks that the Enlightenment has been misunderstood as a doomed project aimed at perfecting humanity by repressing emotion. But that was never the intention, says Pinker, because humans are inescapably emotional beings, made from what Kant famously called the “crooked timber of humanity”.

Those unpredictable impulses that lead to strife, violence and war will always be with us. What’s at issue is how we govern those impulses – through religious dogma, tribal lore and superstition, or by reason, debate, the rule of law? Pinker suggests that latter approach has delivered undeniable moral advancement.

“Slavery used to be practised by every single civilisation,” he says. “Now it is illegal everywhere on Earth. The concept of equal rights for women wasn’t a concept until a couple of hundred years ago. Now it is part of the explicit belief of all world bodies and most countries. The rights of children not to be exploited for their labour, racial equality, religious tolerance, freedom of speech… it’s very difficult to find clear statements of these values before the Enlightenment. There were some statements in ancient Greece, but they certainly didn’t carry the day then. In almost everything that you could take as an index of moral progress, the data show that we have been making it.”

It’s just the kind of speech that will be pilloried as “Panglossian”, after Voltaire’s relentlessly optimistic Professor Pangloss in Candide. But as Pinker correctly notes, Pangloss was a satire on theodicy, the belief that God had created the best of all possible worlds. Professor Pinker, by contrast, believes the world is inherently unstable and nothing is guaranteed. His concern is to make things better. And you can only do that if you first acknowledge the improvements that have been made. Enlightenment Now has made it extremely difficult to ignore them, even if you’d much prefer a spot of crystal healing and a Deepak Chopra tape. Namaste.

• Enlightenment Now by Steven Pinker is published by Allen Lane (£13.99). To order a copy for £11.89 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our Editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important because it enables us to give a voice to the voiceless, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. The Guardian’s editorial independence makes it stand out in a shrinking media landscape, at a time when factual and honest reporting is more critical than ever. The Guardian offers a plurality of voices when the majority of Australian media give voice to the powerful few.

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning: Jeremy Lent, Fritjof Capra: 9781633882935: Amazon.com: Books

Editorial Reviews

Review

“This fascinating, page-turning exploration of the human journey from the stone age to the space shuttle gives us powerful new ways to see ourselves. Deeply researched, and written with great clarity and style, this book is also full of hope about humanity’s possibilities in the twenty-first century.”

—Rick Hanson, PhD, author of Buddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

“A tour de force on the biological and psychological background of the human predicament. If you are concerned about our future, you should know about our past. This amazing, well-documented book should be read by every college student and every congressman.”

—Paul R. Ehrlich, author of Human Natures

“A brilliant deep dive into the history of human cultures that brings us to today’s cultural dysfunctions that threaten the planet. Insight, illumination, and potential ways out of the seeming dead end that we’ve walked ourselves into. I would recommend it!”

—Thom Hartmann, author of The Last Hours of Agent Sunlight

“In prose that is a joy to read, Lent takes us on a tour of human history, guided by systems theory and cognitive science, to argue for the prominence of culture and the habits of the mind in shaping our collective destiny. If you’ve been too busy for the last twenty years to pay attention to the big ideas about the nature of the human animal, the engines of history, our place in the biosphere, and the shape of things to come, Lent can bring you up to date painlessly.”

—J. R. McNeill, University Professor, Georgetown University, and author of Something New Under the Sun

“The Patterning Instinct is a must-read for anyone concerned about the future of humanity. The book delves beneath the surface of problems facing our world today to examine the dominant cultural assumptions that lie at their root. The book thoughtfully traces how views about human nature and the natural world in both Eastern and Western culture have shaped history and how the emerging global culture of connectedness and the systems view of life may hold the key to humanity’s evolution and future survival.”

—Atossa Soltani, Amazon Watch founder and president

“This breathtaking book is already a classic. With its unique synthesis of thought history, actual historical events, and cultural patterns, it does what no other work has achieved since Lovejoy’s The Great Chain of Being. Lent explains in one sweeping argument why global civilization has separated from life. And he shows how we can find our way back into it. Lent narrates the history of humanity’s growing alienation from a shared biosphere and from our own feeling bodies with the suspense and art of a novelist. It is heart-wrenching to see to what degree thought patterns can form not only our worldview, but the actual world, handing it over to destruction. The good message though is Lent proves that humanity’s destructiveness is not God-given; it is, as any cultural pattern, reversible. That is our chance.”

—Andreas Weber, author of The Biology of Wonder: Aliveness, Feeling, and the Metamorphosis of Science

“Shell-shocked liberals and progressives are casting around to explain the political setbacks of 2016. The Patterning Instinct tells us that seeking answers from recent history is likely to prove forlorn; deep-seated patterns in the way we both think and behave have predisposed us to acting in ways that are self-evidently irrational and against our own interests. To have any hope of transforming this perverse and potentially apocalyptic worldview, we will need to dig much deeper into our own history—and this extraordinary book provides an authoritative and inspirational guide.”

—Jonathon Porritt, environmentalist and author

----

About the Author

Jeremy R. Lent is a writer and the founder and president of the nonprofit Liology Institute, dedicated to fostering a worldview that could enable humanity to thrive sustainably on the earth. The Liology Institute (www.liology.org), which integrates systems science with ancient wisdom traditions, holds regular workshops and other events in the San Francisco Bay Area. Lent is the author of the novel Requiem of the Human Soul. Formerly, he was the founder, CEO, and chairman of a publicly traded Internet company. Lent holds a BA in English Literature from Cambridge University and an MBA from the University of Chicago.

Product details

Hardcover: 569 pages

Publisher: Prometheus Books (May 23, 2017)

----------

› Visit Amazon's Jeremy Lent Page

Follow

Follow on Amazon

Follow authors to get new release updates, plus improved recommendations and more coming soon.

Learn More

Biography

More info at: www.jeremylent.com

Jeremy Lent is an author whose writings investigate the patterns of thought that have led our civilization to its current crisis of sustainability. He is founder of the nonprofit Liology Institute, dedicated to fostering an integrated worldview, both scientifically rigorous and intrinsically meaningful, that could enable humanity to thrive sustainably on the earth.

Born in London, England, Lent received a BA in English Literature from Cambridge University and an MBA from the University of Chicago. He pursued a career in business, eventually founding an internet startup and taking it public.

Beginning around 2005, Lent began an inquiry into the various constructions of meaning formed by cultures around the world and throughout history. His award-winning novel, Requiem of the Human Soul, was published in 2009. His most recent work, The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning, traces the deep historical foundations of our modern worldview.

Lent is currently working on his next book provisionally entitled The Web of Meaning: An Integration of Modern Science with Traditional Wisdom, which combines findings in cognitive science, systems theory, and traditional Chinese and Buddhist thought, offering a framework that integrates both science and meaning in a coherent whole.

He holds regular community workshops to explore these topics through contemplative and embodied practices in the San Francisco Bay Area.

------------------

Customer reviews

4.3 out of 5 stars

----------------

Top customer reviews

Brian Hines

5.0 out of 5 starsFacts are good but not enough. Humanity needs an overarching cognitive makeover.July 6, 2017

Format: HardcoverVerified Purchase

A big reason why I liked The Patterning Instinct so much is that it hits the sweet spot between science and philosophy. Or, between facts and meaning. Jeremy Lent's core message is that we humans view information about reality through overarching cognitive lenses -- which we generally take for granted as being oh-so-obviously-true rather than recognizing them as subjective cultural inventions.

This explains why elephants around the world live their lives in very similar ways, whereas us Homo sapiens have developed a dizzying variety of ways we look upon existence. Lent notes that Dualism is a common approach to cognitive patterning where the cosmos is divided into the physical here-and-now and a supernatural there-and-then.

Lent persuasively argues that the Chinese world view is a better model for humanity in the 21st century than outmoded ways of thinking that view "nature as a machine," or "nature as something to be controlled." An avid dualist would add "nature as irrelevant," since dualistic religions such as Christianity and Hinduism view this world as a temporary stepping stone to a higher spiritual reality; hence, a place to be escaped from rather than a permanent abode.

Being attracted to Chinese philosophy, particularly Taoism, I enjoyed his praise of Chinese ways of thinking. They are naturalistic, compatible with modern science, and more systems oriented than reductionistic. Still, it's hard to say that either ancient or modern China is a model for how the United States, or any other country, should approach our pressing national and global problems today.

My only real criticism of The Patterning Instinct is that after spending about 400 pages cogently describing how various human ways of looking upon the world have gotten us to the not-so-great place we are today, the final chapters were a bit of a letdown. I was hoping for more specific descriptions of how it will be possible for massive numbers of people to embrace cognitive patterns that will bring us together, rather than apart; solve environmental problems like global warming, rather than ignoring them; view humanity as being an integral part of the natural world, not a domineering species that can run roughshod over the Earth.

I have a feeling that Lent ran out of pages, not out of ideas. This leads me to hope for a sequel to The Patterning Instinct that briefly reiterates how we got to the cognitive patterns which now are screwing up the world, and then talks in depth about how a re-patterning process can occur on a global scale.

Me, I have little or no idea how this can happen. The Taoist side of me thinks, "It could happen naturally, not much effort required." Well, maybe. But I'm worried that changing people's world views will happen too slowly given how rapidly existential threats to our existence are evolving.

Here's a key quote from the book: "As its heart, the crucial question is whether there is ultimately such a thing as the Truth, as opposed to cognitive constructions creating relationships between coordinates that are always true." (p. 353) In other words, facts are not enough. Yes, they often are lacking, especially in these Trumpian times. But even if science and scientifically-minded citizens were able to present us with perfectly true facts about the world, our instinct for patterning would demand that we weave those facts into a web of meaning.

The nature of that web, that pattern, is the key to what the future holds for humanity. Science-loving people such as me like to think that more knowledge is all we need. The Patterning Instinct went a long way toward ridding me of this belief. What we need is a large-scale cognitive makeover. Many millions, if not billions, of people need to embrace a way of looking upon the world that is both fact-based AND values what the world needs so badly now. As Lent says: (p.441)

"In diametric opposition to the dualistic framework of meaning that has structured two and a half millennia of Western thought, the new systems way of thinking about the universe leads to the possibility of finding meaning ultimately through connectedness within ourselves, to each other, and to the natural world. This way of thinking, seeing the cosmos as a WEB OF MEANING, has the potential to offer a robust framework for the Great Transformation values that emphasize the quality of life, our shared humanity, and the flourishing of nature."

Read less

26 people found this helpful

---

Lion Goodman

5.0 out of 5 starsA Fundamental Understanding of MindJanuary 24, 2018

Format: Kindle EditionVerified Purchase

As a student (and teacher) of consciousness, beliefs, psychology, and human nature, I am thoroughly enjoying this articulate exploration of the very root of consciousness, beliefs, and the structure of mind. This is a thorough and well-researched book, yet highly readable and easy to learn from. I will be recommending this book to all of my students, in my Clear Beliefs Coach Training. Everything I discuss in my program has this basis... we create our reality with our beliefs (Lent calls it patterning). You are not your patterns. You HAVE patterns, and you can change them. A great book that supports the fundamental understanding of Mind.

---

Tim Knight

5.0 out of 5 starsOne of the best books I've ever read.......November 27, 2017

Format: HardcoverVerified Purchase

Now that I've finished reading the entire book, I want to say once again that not only is it terrific, but it's got to be one of the best books I've ever read. I cannot recommend it strongly enough. It delves into Western Philosophy, Eastern Philosophy, ethics, science, history, religion, racism, the exploitation of man, ecology, international relations, the age of the explorers............it is a smorgasbord of information woven together into a volume which is educational, inspiring, and sobering. Marvelous!

-----

Amazon Customer

5.0 out of 5 starsT

To make matters worse, globalization and rise of the “service economy” has ...July 28, 2017

Format: Kindle EditionVerified Purchase

Our societies, our ecosystems, and our planet seem to be coming apart before our eyes. The earth faces potentially catastrophic climate change, disruption of fresh water and nitrogen cycles, nearly ubiquitous disruption of ecosystems, and may well be at the beginnings of a sixth mass extinction event. Our societies are rapidly losing cohesion. Our economies now exhibit the most pronounced wealth and income inequality in history, and along with it, the erosion of our democracies to the point at which most governments are thinly disguised corporate oligarchies. To make matters worse, globalization and rise of the “service economy” has led to a shredding of the fabric of community cohesion. If that were If that were not enough, the increasing secularity of our society has led to a pervasive nihilism. As an atheist, i'm not pushing for religion, rather lamenting the fact that in the western worldview that dominates today’s neoliberal societies, spirituality has long ago been hijacked by judeo-christian religions, so that with increasing secularity we observe a concurrent loss of meaning. The elephant has entered the room...in the face of this existential crisis, we seem powerless to make a concerted globally cooperative effort to save ourselves. Why? In The Patterning Instinct, Jeremy Lent begins with a simple observation: Root metaphors combine to create a cultural worldview that shapes societal values, and these values shape history. He attempts (quite successfully) to answer the question: If the confluence of our core metaphors constrain the way we see the world and the paths we follow, is it the case that to change the disastrous direction of our society we must change these core metaphors? But if we hope to change them, we must both identify their essence and understand how they have evolved. With an understanding of the evolution of root metaphors, and how they constrain societal directions we may hope to change the direction of history before it is too late.

In the tradition of such works as The Ascent of Humanity, and the Empathic Civilization, the Patterning Instinct takes a deep, holistic ,and unflinching look at the evolution of human culture from a systems view of life perspective, and through a uniquely cognitive lens. Throughout the meticulously referenced work, Jeremy Lent focuses his exposition on a complex systems approach paying careful attention to positive and negative feedback loops where present, and considering the interactions between linked systems. The underlying metaphor is that living systems form an intricate tapestry of nested networks of networks over many orders of magnitude. Hence, while it is clear that individuals possess agency, every part of the living earth is interconnected in such a way that individuals are in fact only semi-autonomous.This leads to a different kind of history.

At this point, a brief aside on the systems view of cognition is appropriate. Underlying the systems view cognitive approach is the Santiago school of cognition which has grown out of the seminal work Autopoiesis and Cognition by Maturana and Varela. Originally trying to understand some of the enigmas in color vision, the two researchers developed a definition of living systems demonstrated to be a necessary, and for the biological world sufficient definition of life(interestingly S.A. Kaufman in “Reinventing the Sacred” starts from first principles and arrives at a similar definition for a minimal autonomous agent). Simply, an autopoetic system structurally embodies a web of linked interactions capable of sustaining itself within a boundary of its own creations which is thermodynamically open(to food and energy), but operationally closed. That last bit means that the organism is only disturbed by its environment, but the resulting actions are determined by its internal structure alone, the equivalent is true for “ the environment” from the outward perspective.This is a very complex area ( for deeper understanding see “ The tree of Knowledge” by Maturana and Varela, “Mind in Life” by Evan Thompson, or A Systems View of Life by F. Capra and P. Luisi) but a couple of key take home messages are important here. Firstly, the process of life at all scales of organization is fundamentally a process of knowing and being known...life is a cognitive process. Secondly, the biosphere is a fractal tapestry of intertwined, and interacting nested networks of networks of autopoietic systems over many orders of magnitude. To navigate such a tangled web, all organisms, through recurrent interactions and mutual structural coupling(systemic memory arising from contingency based history), develop simplifying heuristics so that meaning (with respect to the organism’s internal autopoiesis) can be obtained in real time. The idea is that autonomous subjectivity(feelings, emotions, desires, intentions), through recurrent interaction, leads to instincts. As humans evolved increasingly sophisticated patterning ability leading to symbolic languages and birth of the metaphor, our meaning heuristics could be directly passed on to younger generations, honed collectively by social groups, and themselves become subject to selective forces(at a higher scale of organization). From this perspective, the author traces the evolution of major cultural metaphors and resulting cosmologies that have shaped human history since the agricultural revolution.

Rather than attempting to isolate any simple causal influences, Jeremy states that cultures shape values and values shape history. This pays full heed to a major positive feedback loop in human societies, namely worldviews shape human intentions, intentions determine the institutions and technology societies construct, institutions and technologies in turn shape values and worldviews. With this in mind, the author is careful to view history through a cognitive lens. Careful reading of the vast majority of history and anthropology for instance reveals an understandably human, but nearly universal tendency to color insights in the frame of prevailing contemporary worldviews. With impeccable scholarship Jeremy makes the effort to view events in the context of the worldviews/cosmologies/mythologies that prevailed in each particular time and place.

Jeremy starts by tracing the evolution of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the human brain and its necessary role in the rise of the unique human ability ( and relentless drive) to find meaningful patterns in the universe, and construct explanations for what we observe. Convincingly, he argues that rather than possessing a language instinct, humans exhibit a patterning instinct mediated by the PFC, that facilitates the learning of language in infants. Evidence is presented to demonstrate that infants can distinguish between phonetic units, and by nine months or so, distinguish only those present in their native language. Further, it is demonstrated in an array of studies including some stunning results for bilingual speakers and isolated tribes, that perceptions and frames of understanding are strongly influenced by the language one speaks. From there, the evolution of core metaphors and rise of cosmologies are examined as they split into two major groups, the dualistic indo european cosmologies, and the holistic cosmologies of china. The resulting worldviews lead to vastly different ideas about our relationships to nature and each other leading to vastly different attitudes and intentions towards science, technology, political and intergroup relations. Some fascinating questions are addressed from this fresh and unique perspective. At the time of Columbus, the Chinese were far superior technologically to the Europeans, why was it that the Europeans conquered the world? The chinese had all the preconditions for a scientific and industrial revolution hundreds of years before the europeans, yet this did not occur in China. The traditional view, colored by our own worldview, is that this was a failing on the part of the chinese, was it, or is there something about the vastly different cosmologies of China and Europe that shaped the history we observe? For instance, the stirrup and gunpowder were known in China many centuries before in Europe without being particularly disruptive, yet when these technologies arrived in Europe they revolutionized warfare in each case; could it be that the Chinese viewed technologies with an eye towards harmony rather than dominion? The early Muslims had among them great scholars in science and mathematics, they also had all the seeds for a scientific revolution before the Europeans, what was different between the European christians, and the muslim world that led to the scientific revolution for the one, and religious fundamentalism for the other? The prevailing view is one of great antagonism between christian faith and scientific investigation, this is clearly true of contemporary christian fundamentalism, but given the hegemony of the catholic church in Europe through the middle ages, is it even possible that the scientific revolution could have occurred without the support of the church? For that matter, is there any inconsistency between the clockwork universe of Descartes, and the creator god of christianity? What is the common intellectual thread that unites Plato, Descartes, and Ray Kurzweil? These and many other provocative questions are answered compellingly while little known historical developments are revisited in a new light. The Patterning Instinct is a stunning achievement.

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning by Jeremy Lent | Goodreads

Preview

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

by

Jeremy Lent (Goodreads Author),

Fritjof Capra (Foreword)

---------------

4.23 · Rating details · 102 Ratings · 20 Reviews

This fresh perspective on crucial questions of history identifies the root metaphors that cultures have used to construct meaning in their world. It offers a glimpse into the minds of a vast range of different peoples: early hunter-gatherers and farmers, ancient Egyptians, traditional Chinese sages, the founders of Christianity, trail-blazers of the Scientific Revolution, and those who constructed our modern consumer society.

Taking the reader on an archaeological exploration of the mind, the author, an entrepreneur and sustainability leader, uses recent findings in cognitive science and systems theory to reveal the hidden layers of values that form today's cultural norms.

Uprooting the tired clichés of the science-religion debate, he shows how medieval Christian rationalism acted as an incubator for scientific thought, which in turn shaped our modern vision of the conquest of nature. The author probes our current crisis of unsustainability and argues that it is not an inevitable result of human nature, but is culturally driven: a product of particular mental patterns that could conceivably be reshaped.

By shining a light on our possible futures, the book foresees a coming struggle between two contrasting views of humanity:

- one driving to a technological endgame of artificially enhanced humans,

- the other enabling a sustainable future arising from our intrinsic connectedness with each other and the natural world.

This struggle, it concludes, is one in which each of us will play a role through the meaning we choose to forge from the lives we lead. (less)

Hardcover, 569 pages

Published May 23rd 2017 by Prometheus Books

------

What patterns of meaning structure your own life? Where did those patterns come from?

See 2 questions about The Patterning Instinct…

Mar 16, 2018Trevor rated it it was amazing

Shelves: economics, evolution, history, philosophy

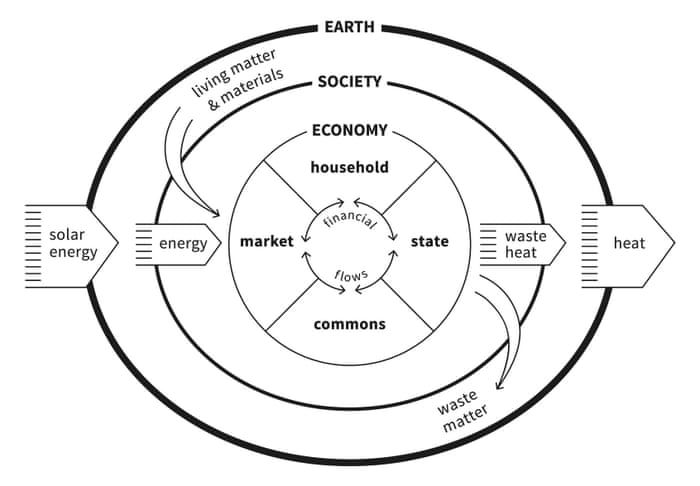

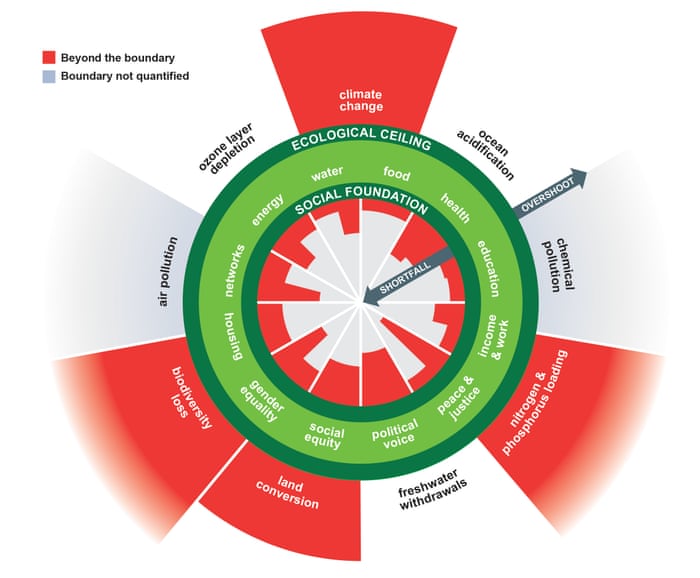

It is funny how books seem to find me sometimes. I reviewed Small Change last week and then Aaron recommended I read Doughnut Economics. I can’t say the idea filled me with much joy – I had a horrible feeling it would be something like ‘economics meets Homer Simpson in this fun-packed…’ oh god, no, kill me now. But it proved to be one of the best books I’ve read in a while – she’s both super smart and intensely interesting.

Then during the week a friend of mine sent me an article by George Monbiot about Pinker’s new book on the Enlightenment and that then said that both Doughnut Economics and this book were well worth reading – actually, what he said was even better than that: “While Pinker is lauded, far more interesting and original books, such as Jeremy Lent’s ‘The Patterning Instinct’ and Kate Raworth’s ‘Doughnut Economics’, are scarcely reviewed.” And since I was really enjoying my doughnut book, I figured it was pretty likely I would enjoy a good pattern book too… Ironically enough, this one gets it title in part as a polemic with Pinker and his language instinct. Wheels within wheel, guys, it turns out it’s all just wheels within wheels.

I kept thinking of Hegel’s Philosophy of History while reading this. Not that this is really trying to stamp the final and ultimate true interpretation of the history of the world, but he is trying to show the kinds of patterns that underlie peoples’ understanding of the world and how these make for particular interactions between people and between people and nature. I can’t remember which of Foucault’s books says that we don’t do history so as to understand the past, but rather to understand the present – but that’s pretty much the point of this book too.

There’s a kind of subplot to this book, that you only really get at the end – and that is summed up by Gramsci’s most famous quote about being a pessimist because of intellect, but an optimist because of will. To misquote someone else mentioned in this book – only a fool or an economist could look at the world at the moment and not be terrified for our future. As Doughnut Economics points out, our current paradigm thinks it is perfectly fine that we need to have endless economic growth on a finite planet and since that necessarily means destroying the basis of human existence, our current paradigm is one that will ultimately lead to the catastrophic failure of our societies and civilisation – unless, of course, we make fundamental changes to how we live. But to do that we must make fundamental changes to how we think about and understand the world – probably the hardest part to the change. This book says that we have made changes as great as this as a species before – the problem this time is that we need to do it consciously and outside of our immediate self-interest – not something we selfish and greedy humans have ever proven particularly good at. (Did I mention pessimism of the intellect???)

Except that if there is one thing that looking at our history and archaeology as a species shows us is that humans have come up with a remarkable variety of ways of understanding the world, and that small groups of people determined to effect change can be devastatingly effective. I need to quote this bit, which he says just before he uses that famous Mead quote:

“Political scientists have studied the history of all campaigns since 1900 that led to government overthrow or territorial liberation, and they discovered that no campaign failed once it achieved the active and sustained participation of just 3.5 percent of the population.”

If that doesn’t give you optimism of the will, I’m not sure what will.

But this is just the last chapter or so – the rest of the book is a fascinating run through the history of humanity’s various understandings of the relationship between themselves and their universe. What is particularly interesting is the deep variety, but also the cross-fertilisation that has existed between these traditions.

This book is quite strongly influenced by Jared Diamond’s Germs, Guns and Steel – but he argues with that book as much as he promotes it as being essential reading (something I would do too – and by the way, this book ends with an annotated bibliography, what a bloody useful thing that is). In some ways this book is similar to Diamond’s, but less about how civilisations rise and fall and prosper or struggle due to their environmental circumstances, but about how their fundamental philosophical patterns of thinking impacts how they engage with the world and therefore how they will interact with other civilisations and so on. So that the philosophical and spiritual traditions that started in India, China, Greece or Palestine all expressed different relationships to knowledge and different expectations based on either harmony with or stewardship over the world. So that Eastern ways of understanding the world stressed relationships and interconnections, while Western notions stressed a kind of hidden eternal truth that needed to be uncovered and that then granted access to ultimate control. So, one tradition sees humanity within the world, and the other as humanity outside the world – this is, of course, a gross over-simplification, and one the book adds much more nuance to.

As is stressed repeatedly here – the metaphors we used as a civilisation reflect how we frame the world and therefore also how we interact with it. In the Western framing those metaphors too often involve constraining nature, subduing it, and ultimately replacing it with the power of reason. This is reflected in our religion which stresses that in the beginning was the word and that the word was God – it is reflected in some of us desiring a time in the not too distant future when we become ‘post-human’, when our brains will be uploaded to a computer and we become immortal.

But not all human philosophical traditions have the same desires as the current and dominant Western one. Rather, many other traditions stress the interconnectedness of the universe and also the communal nature of human societies. One of the more interesting observations in this book – and I don’t know how true it is, as my understanding of non-Western traditions is far too limited – but he says that while other traditions have sectarian wars and so on, generally these did not end up in acts of genocide – in the way the Old Testament demands from the Jews as they conquer those tribes already in the ‘holy lands’. Such single-minded certainty of the need to eradicate all other voices is a particularly Western affliction and one that is at odds with humanity’s ongoing survival and that of our civilisation.

This is an interesting book for many reasons – it gives a nice series of thumbnail sketches of some of the most important philosophical and spiritual traditions. It explains how these helped develop the social psychology of the peoples of the nations that have been held under the sway of these traditions – and it therefore gives some hope that maybe, just maybe, understanding that since such a variety philosophical traditions have existed and that they are human inventions we have developed to help us understand the world, and since it is becoming increasingly clear these aren’t working particularly well at the moment at helping us understand and be in the weld, that maybe, just maybe, we will find the courage to change how we understand the world and change how our societies interact with the world before it is ultimately too late.

Intellectually, I don’t see all that much hope of this happening, of course, but then, if only 3.5% of us can find the will, change is inevitable.(less)

flag33 likes · Like · 14 comments · see review

==============

Nov 05, 2017Emma Sea rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

Excellent book, for all it was a little heavy on the generalizing in places. Lent also doesn't address the fact that Neo-Confusionist stability relies on humans accepting their place and fitting in i.e. it sucks to be a woman, a minority, a human with an intellectual or physical difference, a member of the non-elite. Feminism grew within the Western individualistic framework. Can you have personal freedom within an interconnected web that emphasizes the overarching importance of society vs the individual? Still, I definitely rec this for everyone interested in the possible directions for our culture over the next 80 years.

Kindle book finishes at 62%, the rest is references. (less)

flag19 likes · Like · 3 comments · see review

Sep 01, 2017David rated it liked it

Shelves: 21st-century, academic, cultural-history, history, science

Although Lent attempts to connect the scope of this book with that of Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel it ends up being nothing more than a contemporary Leftist attempt at Cultural Determinism. Not to say this is entirely incorrect but this approach has a tendency to unmoor events from an external reality and objective facts. The reason this is a bad approach is that subsequent academics and political demagogues can further remove humanity from a shared experience in the name of Utopian idealism and could visit the suffering of Soviet Russia and communist China (not to mention the French Revolution) upon the world yet again.

Though Lent is serious minded, this book is little more than jumped up cultural determinism and may be safely avoided by all serious students of the human condition: in the same way as the Frankfurt School, Critical Theory, and Cultural Marxism may be.

Rating: 3 out of 5 Stars (less)

flag4 likes · Like · 7 comments · see review

May 12, 2018Tom LA rated it it was ok

Listened to audiobook, but I couldn’t get further than 50%. I found it too repetitive, bland, and not really bringing anything of substance. Like another reviewer said, the author has a strong bias for cultural determinism, and he’s writing with an agenda. What you get is a lot of anthropological and sociological topics with a vague “the ancient past was golden, today all is shit” overarching narrative. No, thanks.

flag4 likes · Like · comment · see review

May 18, 2018Jim Angstadt added it

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

Jeremy Lent (Goodreads Author), Fritjof Capra (Foreword)

In spite of a foreword, preface, and introduction that take 32 pages, I had a mistaken impression of what this book was about.

Part 1, "Everything Is Connected", was a fascinating discussion of how the prefrontal cortex grew in early man to meet changing needs. This growth included an increase in size, and, more importantly, an ability to handle abstract ideas. The author continues with the shift from hunter-gatherers to an agriculture basis, discussing the rise of a hierarchical model and an increase in anxiety due to a sometimes uncertain future.

Thousands of years pass. Now the focus in on the notion of dualism, a contrast between the western concept of opposition and the eastern idea of harmony. 130+ pages later, I was numb, and thinking of DNF.

In the third major part, the author applies dualism to the conquest of nature. In a methodical and un-hyped discussion, he addresses many of the environmental issues that we currently face. One can now see how the concepts of dualism have given us a frame of reference that may not be sufficiently helpful in reaching a solution to our problems.

The last small part is focused on whether a solution is possible and how it might happen. One is hopeful, but a lot of change is needed in a short amount of time.(less)

----

Dec 19, 2017Jonathan Latham rated it it was amazing

This is a really tremendous book for understanding some of the key events and strands of human intellectual history. Jeremy Lent has a great way of pulling out important threads, especially in the development of religions, and the broad reading and independent-mindedness to do so. His search begins with the separation of homo species from other primates and goes right up to the present day. Some of the events that Jeremy Lent describes I was already familiar with but I always found his interpretations fresh, concise, often helpful ,and only incorrect on very minor issues. Some of the developments and intellectual currents he describes, such as the transition from animist to human deities and the development of Chinese philosophy since Confucius, were almost entirely novel to me. His ultimate point is that we live in a world of unexpected choices, we dont have to see the world in the narrow way we now typically do, and that is an extremely important message of hope. He used his research to extricate himself from an existential crisis and we can too.

I do have some quibbles though. He organises the book loosely around an ill-defined "patterning instinct" whose uniqueness and validity is unclear and it makes no real contribution to the book. Plus, an instinct is one of those concepts often invoked to narrow human potential, exactly the kind of genetic determinist thinking the book is intended to refute. So its use in the title and the hook seems unfortunate.

Ultimately too, the book ends weakly, with no real recommendations and pointers, which to me implies that his enquiries, though profound, are nevertheless slightly off-track. Somehow he lost the scent. The real book that will blow apart the Western cultural mindset has yet to be written. The Patterning Instinct though, is still easily 5stars since for most people it will substitute and far exceed a conventional liberal arts education, and for anyone who wants to change the world or understand themselves it will be both an inspiration and a primer. (less)

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Jun 20, 2018Keith Akers rated it liked it

This book is a brilliant but bulky first draft that badly needs to be edited. This ambitious doorstop of a book is much too long (569 pages) and needs to be cut by about half, with many sections cut out entirely or brought into better focus. It doesn't quite deliver on its premise and promise, but it does say enough to make it quite worth looking at. Therefore, I'd really say that this book rates 5 stars for "you should look at it" but only 3 stars for "you should read the whole thing." Let me explain.

The idea of a cultural history explaining how our environmental crisis arose out of cultural factors is a key reason I picked up and read the book. I am grateful for his numerous references to rapid cultural and social transformation, e. g. China in the 20th century, so clearly rapid cultural and social transformation is possible, and given the environmental crisis, something that needs to happen in a hurry.

Culture? Environmental crisis? Lead me on! It starts out with a bang, but gets bogged down in the middle. He could have cut the book by at least 50% --- get rid of much or most of parts 2, 3, and 4. He should lose the part where he tries to explain the cultural history of the west, and then China, India, and everything else for the past 10,000 years. Please just focus on cultural attitudes and our present-day environmental crisis with some illustrations from our past.

Early on, when he discusses the ancient Greeks and Plato, my mind started raising red flags. He says that Plato is responsible for our dualistic world view. All right, fine. I was a philosophy major (and even did some graduate work), and I think I know something about Plato. So what does he say about Plato? He starts talking about Plato's theory of the forms. He doesn't cite anything in Plato, but quotes from secondary sources, such as Francis Cornford's book on Plato.

Francis Cornford is a respected commentator on Plato who I am sure has followers, but he is hardly the last word on Plato, and I think he is dead wrong about Plato's Theory of Forms. Plato doesn't have a theory of forms. That Plato has a "theory of the forms" in the first place is a misconception which Cornford unfortunately seems to be somewhat responsible for. The only place in Plato where there is extensive discussion of the so-called "forms" is in the "Parmenides," in which the Young Socrates talks with Parmenides and the conclusion is that the theory of the forms is to be rejected.

Most of Plato's writings are agnostic and negative in their outcome. A plausible theory is put forward, and then shot down. In the "Theaetetus," one of Plato's key "mature" dialogues, for example, Socrates discusses three theories of knowledge: knowledge is perception, knowledge is true opinion, and knowledge is true opinion plus reasons. We wind up rejecting all three. In the Seventh Letter, he explicitly says that his doctrine cannot be taught like other disciplines, but that it catches fire in the mind of the student after much preparation and study. Plato's dialogues often have memorable mystical myths, such as the myth of Er in the Republic and the theory of recollection in the Meno. Plato is a mystic; he doesn't teach "explicit" objective knowledge or science in the sense that we think of today. For science, you need to go to Aristotle.

So, to get back to Lent, the author presents Plato all wrong. I see that this doesn't fatally damage his thesis, because this kind of dualism is clearly present in many Western thinkers, such as the early orthodox Christian theologians like Augustine as well as Descartes, Kant, and so on. However, at this point I am having to supply my own rationalizations to help the author out, and I start to lose interest in everything else he has to say. He is going to rely on secondary sources, albeit plausible secondary sources, and so we are going to get a long-winded, but fuzzy, intellectual history of the West, and later the East, too.

I haven't gone through all his sources, but I see that he even relies on secondary sources for writers for which there could easily have been explicit references. For example, at one point (p. 378) he quotes Nietzsche as saying "God is dead." Oh yeah, I say to myself, I remember a big discussion of that in the 1960's! I wonder where Nietzsche says that? I turn to the footnote, and I get a secondary source, a reference to Peter Watson's "The Age of Atheists." Jeez, Louise! I did a Google search and quickly found the Wikipedia article identifying the phrase "God is dead" as coming from "The Gay Science" and "Thus Spake Zarathustra." Why can't Lent do an extra 45 seconds of research and give us the exact reference? And is this how he is going to do all of his research, and if so, why should I read this?

So in conclusion, this is a fascinating but unfinished book. Send it back to the author with a request for extensive revisions. A cultural resolution to the environmental crisis is possible, in fact, we may be undergoing such a transformation right now. But it might also turn out badly. What kind of cultural transformations do we need for human survival, and how do we get there? I wish someone would write about that.

(less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Mar 10, 2018Ken rated it really liked it

Entertaining read - I read this at the same time as “Enlightenment Now”. Both authors present an interpretation of the swathe of human history and the “reason “ societies evolved as they did. Both use a model of history built upon a very long time scale and apply it to understand the next 50 years - far too shot to be sensitive to the forces they invoke for history. Doesn’t anyone understand the concept of signal to noise anymore? Both authors appear to be intellectually rigorous - and yet their conclusions seem to be based primarily on belief systems. Lent has a strong affinity for the supposed less brutal philosophies of the East, and his argument that cultural norms drive beliefs is more compelling than Pinker or the “Guns, Germs and Steel” deterministic view in my mind. The Patterning Instinct emphasizes the human compulsion to find patterns - perhaps when they don’t even exist(?). That is where I think most of these interpretations of history fall short. Maybe there was no good reason for things to evolve as they did. History is a mystery and the future is ours to see....? But Lent’s assertion that core cultural norms impact belief and this is built into the politics that will drive critical decisions over the next 50 years is important. Understanding the foundations of our belief systems is surely the only way we can challenge them and learn to look outside the boundaries we set for ourselves. Read this book ... (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Apr 25, 2018Red rated it really liked it

Shelves: economy-stupid

A beautyful book with many insights that are put skilled together. So my takeaway is this, some 100K years ago first humans left Africa on a persuit of happiness. The ones that stayed home would become wise. And this pattern continues ever since.

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Jun 05, 2017University of Chicago Magazine added it

Shelves: chicago-booth

Jeremy Lent, MBA'86

Author

From the author: "This fresh perspective on crucial questions of history identifies the root metaphors that cultures have used to construct meaning in their world. It offers a glimpse into the minds of a vast range of different peoples: early hunter-gatherers and farmers, ancient Egyptians, traditional Chinese sages, the founders of Christianity, trail-blazers of the Scientific Revolution, and those who constructed our modern consumer society.

"Taking the reader on an archaeological exploration of the mind, the author, an entrepreneur and sustainability leader, uses recent findings in cognitive science and systems theory to reveal the hidden layers of values that form today's cultural norms.

"Uprooting the tired clichés of the science-religion debate, he shows how medieval Christian rationalism acted as an incubator for scientific thought, which in turn shaped our modern vision of the conquest of nature. The author probes our current crisis of unsustainability and argues that it is not an inevitable result of human nature, but is culturally driven: a product of particular mental patterns that could conceivably be reshaped.

"By shining a light on our possible futures, the book foresees a coming struggle between two contrasting views of humanity: one driving to a technological endgame of artificially enhanced humans, the other enabling a sustainable future arising from our intrinsic connectedness with each other and the natural world. This struggle, it concludes, is one in which each of us will play a role through the meaning we choose to forge from the lives we lead." (less)

flag1 like · Like · see review

Jun 03, 2018Vivify M rated it it was ok

Shelves: general-interest

The title of this book had me eagerly anticipating a scientific exploration of cognition, and its impact on culture over time. Unfortunately, that was not what I got.

This author has tremendous depth of knowledge of culture and religion, across the globe and through time. His extensive knowledge of religious history is amazing, but exceeds the limits of my interest.

The book introduces concepts of complex systems, and the idea that language and the metaphors we use, determine our cognitive processes and ultimately our actions. It suggests that culture can be viewed as two intertwined complex systems, one tangible and the other intangible. I enjoyed considering these, but aside from presenting the ideas, the book did little to substantiate them.

To me this read like snippings of Sapiens, and Guns Germs and Steel, tenuously connected by a promising but poorly constructed argument.

The author has a strong bias in favour of Chinese culture, and often gushes over the noble ancients. He is clearly very taken by the wholistic nature of eastern cultures. I don't know much about these, and found much that was new and interesting to me. Sadly, I also found myself heavily discounting this information, since the remainder was often weekly argued and downright questionable.

I was happy to broaden my understanding of the forces and interactions that have defined humanity through time and into the present. As he points out, Jared Diamond, Dawkins, Harari and Pinker have discussed this topic in terms of technological, geographical, language, and biology. But, he goes on to say that they have neglecting the impact of cultural and ways of thinking. I'm not sure this is an entirely fair claim. None the less, it would be worth exploring those factors in further detail. If he only brought something to add to the conversation, I would be happy. Unfortunately, I found this book distastefully combative towards all his contemporaries. Throughout, he is arrogantly critical of the aforementioned authors, needlessly accusing all his counterparts of Reductionism and Post modernism. I found it ironic, how this attitude contradicts the wholistic system thinking cultures which he spends so much time gushing over.

Notes:

One of the most interesting parts were the description of how some hunter gatherer cultures keep egos in check. Successful hunters are derided to prevent anyone from feeling above the group. Other social norms enforce extreme sharing of all forms of wealth. This topic is also discussed in the article "Envy's hidden hand" by James Suzman, author of "Affluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen".

Another interesting idea put forward, is that war may be linked to the evolution of cooperation. People who were willing to risk themselves to defend companions, thrived through the strength of their group, and paved the way to armies and war. If I remember correctly this is also discussed by Dawkins in the selfish gene.

Many times I found myself thinking his analysis could have benefited by some application of game theory. Unfortunately, only narratives and tangential facts are offered to support the theories.

He hates on the West, for good reason. But I found myself wondering why he didn't talk about the stoics. It is late in the book, when he does finally discuss them, and then only briefly.

While he extensively covers society from West to East, not much is said about Africa. As someone living in Africa, and mindful of topics such as post-colonial education, I wondered; Is this because he doesn't know much about Africa, or is there simply not much to be said?

He seems to say that the west conquered the world and initiated the scientific revolution, because it had ways of thinking that were sinister. While other parts of the world were happy to live in harmony. And as he put it, didn't usher in the scientific revolution simply because they didn't want too. But I don't see how this substantiates his claims, or tells us very much about the myriad of reasons leading to this state of mind. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Aug 20, 2018Jacob van Berkel rated it it was amazing

Shelves: eastasia, religion

This book is two things:

(1) it's a journey through the 'cognitive history' of humankind. This constitutes the bulk of the book, and covers a lot of ground.

(2) an Elijah-like call to repent, sustainability and connectedness-wise. This constitutes only roughly the last two chapters. And though I think this message is really important, and I'm certainly sympathetic to it, I fear is that a lot of (professional) reviewers will define this book by it, and scare people off in the process.

Because that's the thing with Elijahs and Cassandras: no one wants to listen to them.

And that would be a shame, because I think a lot of people would really really love this book for the (1) part. I mean, if people liked Yuval Noah Harari's Sapiens (and a lot of people did), they will probably also enjoy this book. In fact, they (like me) might enjoy it even more, as Sapiens was only special or good in the first part and a half, in which Harari framed history into the role of the 'stories' people tell each other and the 'imaginary orders' these stories are weaved into. After that Sapiens becomes sort of a standard history textbook, not particularly bad but not particularly good either. The Patterning Instinct also interprets history as (at least partly) idea-driven - Lent says: culture shapes values, values shape history; Harari put it as: the cognitive revolution is the point at which history declared itself independent of biology (paraphrasing both) - but manages to stay fresh and fascinating throughout. The main difference is that Lent focuses on intellectual history while Harari focuses just as much on events.

Anyway, for what it's worth, personally I really loved this book. (For the (1) part.) A good indicator of how interesting a book was to me, or much I learned from it, is the amount of notes I took. Usually I take between 2 and 5 pages (A5 sized) of notes. A little more if I'm completely new to a subject, but even then 10 pages would be exceptional. For this book I took 41 pages of notes, and basically added the entire 'further reading' section to my 'to-read' list. And I wasn't even new to most of the subjects! In fact, a lot of the references were already in my 'read' and 'to-read' lists.

Of course that also means I might be biased, as this book covers exactly the sort of topics I was already clearly interested in. So I will have to be careful and say that maybe or even probably anyone who likes history - especially the big, wide kind, in the vein of Jared Diamond, Ian Morris, or Harari, etc. - will enjoy this book. But will definitely recommend this this book to anyone who is interested in intellectual history (philosophy & religion) of various 'civilizations'.*

_______

* Esp. the religious and philosophical traditions of Chinese, Indian, Greek, and 'Western' civilizations receive a lot of attention in this book, along with the hunter-gatherer worldview & ethic, but Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Persian, Jewish, and Islamic thought are also discussed in some detail; more are mentioned (Incas, Mayans, & al.) of course, but mostly for comparison and not in too much detail. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Jul 29, 2018Warren Mcpherson rated it really liked it

Shelves: ideas

Cognitive history. Exploring core beliefs and understandings, as well as how they change over time in the context of society as a complex system.

The analysis of the original development of language and the dawn of agriculture and the impact of these developments on our belief systems was fascinating. The book follows the development of philosophy in ancient Greece and it impacts on Christianity and Islam. These systems are contrasted with the cultural developments on China. The fawning exploration of Chinese beliefs was new to me and interesting. I don't particularly mind if a discussion is biased, but as the book spent more time comparing religions I felt this was not what had drawn me to it in the first place. It remained informative. In the end, the author spends the last chapter telling the reader what ought to happen in the future. Perhaps this was inevitable.

The book is long, reflecting and referring to a great deal of research. I think it could be better with a clearer synthesis of the books purpose and a review of how each section serves that purpose. I suspect the scope of the book makes the writing process a touch unwieldy so organizational shortcomings are understandable.

One thing I particularly liked was the discussion of reciprocal causality of complex systems.

Overall this is a very informative book on a reasonably novel and fascinating topic.(less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Jul 27, 2018Barnabas rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

Shelves: science

It's a heavy one....

I liked Sapiens, and even more Homo Deus from Harari, and this book is pretty much on par with those, actually in many ways goes deeper and analyses more.

If you consider where is humanity coming from and where are we going (sustainably or not) this book is for you.

Get prepared though that your concepts of mythology, religion, ideals, will be tested as this book is very deep on going back to historical roots.

I believe this is a book to be read or listened to more than once - I thoroughly enjoyed the audio performance, but being honest, it is a tough book to listen to in one setting.

Make you set the time aside to take the mental journey with Mr Jeremy Lent. It is worth it.(less)

---------

Jul 01, 2018Mitch Olson rated it really liked it