2022/08/20

The Light Within as Redemptive Power by Cecil E. Hinshaw

Quaker Pamphlets

Quaker Pamphlets Home

Quaker Pamphlets:

William Penn Lectures

Pendle Hill Pamphlets

Quaker Universalists

Other Pamphlets

External Quaker Libraries:

Pendle Hill Pamphlets

Quaker Universalists

FGC Library

Quaker Electric Archive

Quaker Heritage Press

Street Corner Society

Friends Conference on

Religion & Psychology

eBook

Pamphlet

Printer Friendly

William Penn Lecture 1945

The Light Within as Redemptive Power

Delivered at

Arch Street Meeting House

Philadelphia

by

Cecil E. Hinshaw

President, William Penn College

The Nature of Man

A realistic view of human nature must recognize that we have within us strong and powerful drives toward both altruism and selfishness. Any picture of man as entirely a creature of either of these two urges is true neither to our own experience nor to the best thought of the greatest minds. The relation of these two conflicting parts of our being constitutes a profound dilemma for ethics and religion.

Because of the inner tension caused by this problem, Paul cried out in distress, "For the good which I would I do not; but the evil which I would not, that I practice."1 It was this same inner conflict between sin and purity which puzzled Augustine when he analyzed himself. Perplexed, he said, "The mind commands the mind, its own self, to will and yet it doth not. Whence this monstrousness' And to what end?"2 As a youth, George Fox saw within himself what he termed "two pleadings." Each of these, he declared, strove within him for mastery. Isaac Penington was likewise conscious of this moral and spiritual warfare. Speaking of Satan and God as two opposing kings, he said, "Man is the land where these two kings fight ... and where the fight is once begun between these, there is no quietness in that land till one of these be dispossessed."3

The modern attempt to understand man's nature has tended to obscure this fact of moral dualism. Except for Mary Baker Eddy and a few others whose approach is similar to hers, our modern Christian teaching has not actually denied the existence of the conflict between sin and goodness, but we have accomplished almost the same result as a denial by a preponderance of emphasis upon the good that is in man. Educational theories have hesitated even to recognize the fact of sin, fearing that such a negative approach may itself produce wrong conduct. On the other hand, we are told that we can produce the desired results in moral living by carefully building up the good that is in the child. This so-called positive emphasis seeks to train a child to grow naturally into a good person, never experiencing the kind of moral conflict so vividly described by Paul, Augustine, Fox and Penington.

This supposedly optimistic view of human nature is actually either hopelessly visionary, denying entirely the reality of sin, or it is dangerously pessimistic. The pessimism is clearly seen when we realize that fear of failure is the only good reason for minimizing or dodging the fact of moral conflict. If we are afraid for people to know themselves accurately, to see clearly both the good and bad that is in them, it must be because we fear that such knowledge will increase the prospect of moral failure. We can be both realistic and truly optimistic if we see that, although every man is something of a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, there still can be genuine victory for our higher selves over our lower selves.

Instead of fearing this moral conflict, we ought to recognize it as the source of intellectual, moral and religious progress. The proverb "Necessity is the mother of invention" describes a basic pattern of human behavior - mental activity and strengthened character are our responses to needs, problems, which cannot be solved by habitual responses. Great men have come out of periods of tragedy and struggle because such outer turmoil heightens the inward tensions that are basic to the development of character and insight. Jeremiah's sufferings and his consequent greatness were the direct result of the decadence of his nation. The great spirit that moves through second Isaiah is the refined product of a humiliating captivity. Augustine's own personal moral problem and the death of the Roman Empire are the background of a magnificent life. It took the Crusades and their accompanying suffering and disruption to produce a Francis of Assisi. Fox and the early Quakers came out of troubled times in England. Though we seek to escape problems and troubles, both within and without us, the struggle they produce is actually the prerequisite of growth; even the effort of the oyster to deal with an irritating object introduced into the shell produces a lustrous pearl. "All these troubles were good for me,"4 Fox observed as he looked back in retrospect upon the problems of his youth, temptations so great that he almost despaired of ever conquering them.

There is no easy path to sainthood. Men do not grow into it unconsciously, nor do they achieve it without inner tension. The courageous recognition of this fact is the beginning of spiritual maturity. The selfishness basic to all sin is a present fact; you and I do have deep within us the seeds of sin. We have seen the fruition of those seeds in our own pride and self-centeredness. No veneering of this sin by respectable courtesies and polite mannerisms can change what we know is present within us. Like Paul and Augustine, we have experienced moral failures; if we are honest, we must confess that Paul speaks for us, too, when he says, "all have sinned and come short of the glory of God."5 If we are to be adequate in our religious faith and experience for the needs of our troubled world, we must take into account this inner tension caused by the conflict of these two opposing tendencies within us.

Darkness and Light

The early Quakers, in order to express this moral dualism which they saw in themselves and in others, frequently used the contrasting terms, darkness and light. In describing his early ministry, George Fox wrote, "I was sent to turn people from the darkness to the Light."6 The "children of Light" knew that they had been redeemed from sin and its power, and that conviction and experience was their message. They had experienced the moral tensions which were native to Puritanism, and they had found an answer to them. That answer is the keynote of early Quakerism. Fox expressed it in classic words, "I saw, also, that there was an ocean of darkness and death; but an infinite ocean of light and love, which flowed over the ocean of darkness."7

Without question, the Light within is, in early Quakerism, that which William Penn called "the first principle." Any hesitancy to accept it as such stems either from a failure to study adequately the writings produced by early Friends or from a profound misunderstanding of what the Light within meant to them. The cornerstone of their faith was the belief that Christ did lead and guide them out of darkness into the glorious light of God's perfect love and power. Out of this experience of the redemptive power of the Light came their message of victory over the forces of all unrighteousness.

The Light within was equated by them with Christ. Instead of a vague, impersonal spirit, they believed that Light to be the eternal Christ who had been manifested perfectly in the historical Jesus and who continued to dwell in the hearts of his followers. "Christ is come and doth dwell and reign in the hearts of His people,"8 Fox declared in refuting those who believed that Christ would return in physical form at some future time. The words Light and Christ are so often linked together that they should be recognized as synonymous terms for the early Friends. They genuinely believed that Christ, the same power and spirit which was in Jesus, had taken up His abode in them.

Instead of claiming that they had discovered anything new in Christianity, the Quakers insisted that the principle of the Light had been accepted by Christians of all ages. To support this contention, the Quaker scholar, Robert Barclay, in his "Apology for the True Christian Divinity," gave many quotations from Church Fathers to show that the principle of the Light was an essential part of the Christian tradition. Nor were the Quakers the only ones in their own time who proclaimed the primacy of the Light. Even before the time of Fox and continuing after the birth of Quakerism, there was a group among the Puritans who taught the same central truth of the mystical light of Christ. These men, known as the Cambridge Platonists, insisted that Christ became a reality only as he was personally experienced in the heart of man. Everard of Cambridge wrote: "He lives within us spiritually, so that all which is known of Him in the letter and historically is truly done and acted in our own souls."9 Even the Westminster Assembly of Presbyterian divines professed their belief that Christ is an inner reality, spiritual in nature. The uniqueness of early Friends lies not so much in the teaching of a divine Light within man as it does in the work and power that can be accomplished by that Light.

In our own day, however, we have attempted to put the early Quaker teaching of the Light within on a philosophical basis. We have placed this belief in a logical and philosophical framework that agrees with our own thinking. This has resulted in a large degree of failure to understand the true contribution that early Friends made. Nor has it enabled us to understand accurately what the Light meant to them.

A better way to investigate the meaning to Fox and his followers of the Light within may be to consider the practical function of the Light. Most of Quakerism, especially in its earliest period, tended to be unsystematic in its intellectual formulations. The theology of the movement was, to a very great extent, the theology of the times. George Fox, especially, is not the kind of man who can be understood when placed in a framework primarily philosophical and logical. He lived experimentally and intuitively. Therefore the meaning to him of the Light within must be found in the work of that Light.

Such an approach to the study of the meaning of the Light within is best made through an investigation of the meaning of the term, darkness, which is the opposite of the term, light. As a matter of fact, any kind of light acquires its meaning and significance by contrast with its opposite. The light of the sun is valued by us more highly because of those times when we have not had it. A few years ago the New England hurricane created great havoc and destruction, throwing many cities into total darkness. That night of terrifying wind and shrieking sirens of fire engines remains in my memory as a vivid experience of what darkness can be. The absence of light taught me an unforgettable lesson on the value and function of light.

You and I are more receptive to a picture of light than to words about darkness. By reminding ourselves of all the light we can see, we hope to avoid the unpleasantness of a realistic view of a sinning world. Even though we have to see clouds sometimes, our emphasis is upon the silver lining. So it is that when we have looked at early Quakerism through the rosy lenses of our modern world-view, we have gladly seen it as a picture of triumphant light. We have hurried past the words about an ocean of darkness to the welcome metaphor of an ocean of light. Thus we have often failed to evaluate accurately or to understand the message of Fox - a message which can be grasped only by a full understanding of the darkness out of which he came.

"I had been brought through the very ocean of darkness and death," declared Fox, "and through and over the power of Satan, by the eternal, glorious power of Christ; even through that darkness was I brought which covered over all the world, and which chained down all and shut up all in death."10 When one reads the Journal carefully, the nature of this darkness is clearly seen to be moral and spiritual. From priest to priest he went, seeking in vain an answer to his problem, which he defined as "the ground of despair and temptations."11 Reared in a Puritan environment, filled with the pessimistic teachings of a faith that was obsessed by the sin it believed to be unconquerable in this life, Fox could see no way out of the darkness. Evidence of the extent of his problem are his words of despair: "I could not believe that I should ever overcome … I was so tempted."12 Other people were quite at ease and contented to remain in the condition of moral and spiritual defeat, which was misery to him. "They loved that which I would have been rid of,"13 he complained. Underneath the cloak of piety - respectable forms of godliness so apparent everywhere in Puritan England - the young seeker clearly discerned the selfishness, pride, and lust that yet ruled the hearts of men, including the priests of the steeplehouses.

This analysis of seventeenth century England as a nation in moral and spiritual darkness was echoed by Isaac Penington and other early Friends. Penington's description must have been like a knife to the professing Christians to whom he spoke: "There is pollution, there is filth, there is deceit, there are high-mindedness, self-conceitedness, and love of the world, and worldly vanities, and many other evils to be found in the hearts of those that go for Christians; and purity of heart … is not known."14 Even more stinging were the accusations of Fox: "And are not all professors, and sects of people, such as have the form but are without the power of godliness? Are not people still covetous, and earthly minded, and given to the world, and proud and vain, even such as profess religion, and to be a separated people? Are not professors as covetous and proud as such as do not profess?"15

In his prison epistle, No Cross, No Crown, William Penn became quite explicit in describing the sins of his day and comparing them with the standards of Jesus, who, he said, "came not to consecrate a way to the eternal rest, through gold, and silver, ribbons, laces, prints, perfumes, costly clothes, curious trims, exact dresses, rich jewels, pleasant recreations, plays, treats, balls, masques, revels, romances, love-songs, and the like pastimes of the world."16 The conclusion is obvious that early Quakers saw the moral and spiritual condition of England as a state of apostasy and darkness.

As a study of the moral and spiritual darkness of seventeenth century England gives new meaning to the idea of the Light in early Quakerism, so may a consideration of the darkness of our age make our problem clearer. Until the tragedy of this war came upon us, we endeavored to remain optimistic about our times. Even through the first World War and later in the crash of our financial structure, we kept telling ourselves that our troubles were only temporary and we would soon emerge into the glorious dawn of the new day of progress and light where war would be outlawed and breadlines would exist no more. Our dream has been shattered for most of us today, but there are still some who, unwilling to face the truth of the magnitude of the catastrophe that has engulfed us, bravely whistle in the darkness of our age about the wonderful material advances that await us in the "world of tomorrow." A naive, childlike faith in the fair words of the Atlantic Charter and in the integrity of statesmen sustains them even when the Atlantic Charter is repudiated by its makers.

Others of us begin to wonder whether it is the dawn of a new day or the twilight of an era that is dying. Spengler and Sorokin, prophets of the doom of western civilization, were lightly cast aside not so long ago, but they take on new significance to us now as we watch with foreboding the drawing of peace plans. We wonder whether Jeremiah's words may be applied to those who now forecast a brave new world - "They have healed the hurt of the daughter of my people slightly, saying, Peace, peace; when there is no peace."17 The seeds of racial, class and international struggle now being sown all over the world can only produce a new and more terrible harvest of sin and suffering. Though our faith remains steadfast in the ultimate victory of love over sin, we cannot but realize that an ocean of darkness covers our world now.

If we could believe that our own Society of Friends is not sharing in this decadence, our hope would be greater. Small as we are in numbers, we could be a powerful force either to check the decay of our culture or to build firmly the foundation of a new age. Honesty compels us to admit, however, that we are not qualified for such a mission. Though the sins of the world are grievous, it is our own weakness and impotence, our own lack of power and strength which is our primary problem. Throughout the nation, our meetings, remnants of a once powerful movement to publish Truth throughout the world, struggle to keep from dying. In pastoral meetings, a steadily weakening ministry too often resorts to promotional schemes borrowed from commercialized churches to bolster the falling attendance. Even though such methods may be based upon questionable motives, we gladly announce that the result is an increase in membership and attendance. When the novelty of the attendance-building plan is worn off, we discreetly keep silent about the subsequent drop in interest and attendance. In spite of all our manmade attempts to build institutional loyalty, yearly statistical reports are discouraging. Other sections of American Quakerism report on a similarly pessimistic note concerning membership and the attendance at meetings for worship and business. The few bright spots where meetings are virile and growing serve to show even more clearly the weakness of our Society. Can it be that we are dying?

Dimly aware of our weakness, we seek to find ways to bolster our falling self-respect. We grasp at the straws of praise which others toss to us, we remind ourselves of our virtues and good deeds in all parts of the world, and we recall the past glories of our Society. Underneath this shallow optimism we know the stinging truth of charges that our movement is suffering the same death which is falling upon all Christendom like the soothing sleep of a freezing man.

In the last analysis, however, this darkness that has settled upon Quakerism is the result of personal, individual failure to live victoriously. If we could find within ourselves the miracle of strength and power we need, we could overcome the respectable lethargy of our meetings and transform them into centers of light capable of redeeming our world from its darkness. The surging power of early Christianity could be ours today. God has not lessened His desire to have men become channels for His redeeming love and power. The Light of Christ could illuminate the darkness of our sinful age. A modern Francis of Assisi could even accomplish miracles with the rulers of this world. But no such tidal wave of indescribable divine power and love can break over our darkened world until we rise out of our satisfied complacency and calm indifference.

As the very goodness and respectability of the Puritans kept them from seeing that the Quakers were beyond them in purity and love, so do our virtues and achievements blind us to the dazzling brightness of the life to which Christ calls us. We attend meetings for worship and we please ourselves by self-given praise for our pure form of worship, but we have not known in those times of worship the soul-transforming power that results from utter obedience to the invading love of Christ. We have been respectable and praiseworthy in some of our moral standards, but we have not been willing to let God speak to us on delicate matters of habits of eating, types of amusements, use of our time, and standards of dress and living. We mildly teach and practice pacifism in relation to war between nations, but the revolutionary implications of pacifism - the complete substitution of love and unselfishness for hatred and greed in our relations with all people - we have scarcely dared to contemplate seriously as a way of life. Tested by ordinary problems of human relationships in our meetings, we have failed to demonstrate that we can even get along with each other. We speak of equality for all men because of the Light within, but we fail to give evidence that our words have meaning. Satisfied with mediocrity, contented with our comfortable plans for a secure future, pleased that our sins are seemingly small and overlooked by others who likewise do not desire complete purity, proud that we occasionally deny ourselves in order to contribute to some good cause, we continue to be weighty Friends and important people in our communities, but we have not known the life and power and spirit of those who have dared to be prophets of God.

As a watchdog will not let a herd remain in contented indifference to danger, so does the Light of Christ continually seek to puncture our proud complacency, refusing to let us he entirely satisfied with sin or even a partial goodness. In stubbornness we may oppose the pleading of the Light and give ourselves over to the darkness that blankets our age, but we can never cease to know that God still calls us to the heritage of a Kingdom of light and power. Even more fundamental than the fact of sin is the fact of our relationship with God. This is the message of the story of Adam and Eve. Man may sin and alienate himself from God, but he can never erase his divine parentage. Eternal truth is written in those words in Genesis: "And God created man in his own image."18 It is the same truth which Jesus phrased so perfectly in the parable of the prodigal son. Though we wander far from home, waste our God-given heritage, and surfeit ourselves in the sensual pleasures of this world, it is still true that we belong to God, that we are divine in our origin and divine in our possibilities. Augustine expressed this kinship with God in classic words: "Thou madest us for Thyself, and our heart is restless, until it repose in Thee."19 Because man belongs to God, because eternity has been written indelibly into his heart, his acceptance and practice of sin, encouraged and abetted by a decadent culture, can only result in a moral and spiritual tension of increasing magnitude.

As men and women all over England gathered into bands of Seekers, trying to find a way out of the darkness which bore so heavily upon them, so are men and women all over the world today groping toward a release from the darkness which encompasses our age. Paradoxically, the greater the darkness, the greater is the yearning in the hearts of men for the light to relieve that darkness. In the midst of the frantic attempts of Christian institutions to stay alive, the numbers increase of those who turn away from the Church, sorrowfully seeking elsewhere the answer to the dimly understood urgings of Christ within as He gently leads them to the "well of water springing up into eternal life."20 So it is that God calls us, ever unwilling to let us be satisfied with even our half-goodness. The ocean of darkness is grim and terrifying in its power and extent, but the ocean of light, even Christ within, seeks to save and redeem us from that darkness. The result is war within ourselves, a basic conflict between selfishness and love. Unable to free ourselves of the ideals and visions which a divine light has planted within us, yet drawn inexorably toward sin, we find ourselves faced with an impossible tension, a moral dualism, which is profoundly disconcerting.

The Redemptive Power of the Light

The significance of the Light within for the early Quakers is to be found in the practical solution it brought to the moral and spiritual tension with which they struggled. Other professing Christians of the time insisted with the Puritans that there is no redemption from the power of sin until death. Because they believed the physical body to be a body of sin and death, they maintained, in the words of the Westminster Shorter Catechism, "No mere man since the fall is able in this life perfectly to keep the commandments of God, but doth daily break them in thought, word and deed."21 This meant that a basic moral dualism had to be accepted as inevitable throughout all life. Sin and selfishness cannot be defeated; we can hope to do no more than curb them somewhat. This was the teaching that was given to Fox as a youth and this was the problem that sent him forth on a spiritual pilgrimage. The answer which came to the young seeker was not so much a vision of new knowledge of right and wrong as it was a dynamic to practice what he already knew. Quakerism did not contribute a new code of ethics, but it did demonstrate that those precepts could be followed; it did succeed in fusing the common beliefs of the sectarian groups of the time into a way of life that was actually practiced. Everyone faces the moral and ethical problem of doing what is believed to be right. George Fox found a practical answer to the problem.

We tend today to interpret our movement as a philosophical quest far new knowledge of right and wrong, and we are only secondarily concerned with power to put that knowledge into operation. In fact, we often assume that such a goal is impossible of achievement, that complete control of our wills is beyond our reach. That our pacifism is primarily an intellectual concept is demonstrated by our failure in Civilian Public Service camps and in ordinary business, social, and home life, to show consistently the love and kindness, the patience and faith, which is the very essence of true pacifism. Our problem is basically not one of more knowledge of what to do - we already know much more than we are practicing. We know we ought to discipline our desires, our habits, and our thoughts, and we know we ought not to hate or become angry. What we need is power to put our present knowledge into actual and consistent practice.

Once we have seen this dilemma that we face and have become conscious of the moral dualism that explains our predicament, we are ready to profit from the Truth which Fox so zealously published. The Light within had not only convinced them of sin and shown them a better way of life - it had given them the victory over sin and self that enabled them to live as they knew they ought to live. Power is a key word in the early literature of the group, a word repeated hundreds of times. Though the Quakers, like the Puritans, saw sin in gigantic stature, they had fought their way beyond this gloomy obsession with sin to a glorious realm of light and victory. The very power of a victorious Christ Himself had come to dwell in their hearts. So Penington describes the true Church, a Church saturated with power: "This is the Church now - a people gathered by the power from on high, abiding in the power, acting in the power, worshipping in the power, keeping in the holy order and government of life ... by the power."22

Though they were amazingly consistent in their pacifism, these early Friends freely used the metaphor of war to express this moral victory they believed they had won. They called men to a spiritual instead of a carnal warfare. Life for them involved a struggle of cosmic proportions between the powers of darkness and sin, a fight waged with man as the battlefield. A typical description of this warfare is found in these words of Fox: "Christ came to bruise the serpent's head, and destroy the devil and his works, and to finish transgression, and to make an end of sin, and to bring in everlasting righteousness into the hearts of his people."23 A recent analysis of early Quakerism, made by R. Newton Flew, concludes, "Victory is in the air."24 The Light within had brought genuine redemption from the powers of moral and spiritual darkness and all of life had been transformed from a place of bondage to sin to a realm of marvelous light and purity. With Paul, they cried in triumph, "if any man is in Christ, he is a new creation."25 In ecstasy, George Fox described this wonderful freedom and victory: "Now I was come up in spirit through the flaming sword, into the paradise of God. All things were new; and all the creation gave unto me another smell than before, beyond what words can utter. I knew nothing but pureness, and innocency, and righteousness."26

Are such words the product of nervous excitability and lack of mental balance, or are they actually true descriptions of the lives of these early Friends? Is their claim of a complete victory over sin justified by facts? Were their lives models of purity and holiness? Certainly no one answer applies equally well to all of the followers of Fox, but the negative judgment we must pass upon the "lunatic fringe" of the movement does not detract from the solid worth of the great majority of the Quakers of that period. Perhaps the best evidence of the moral purity of the movement is to be found in the accusation of their opponents that Quaker goodness and piety was but a cloak to cover subversive activities! If their enemies had to admit the high moral quality of the movement and attack it as a pretense, then the Friends must have been reasonably close to justifying the claims of George Fox for them:

"And as concerning the Quakers, what do you say of them? You have seen their conversation: few towns but some of them have been and are amongst you. Do not they fear God? And do not they walk justly and truly among their neighbours, and speak the truth, and do the truth in all things, doing to all no otherwise than they would be done unto? And are they not meek, and humble, and sober? And do not they take much wrong, rather than give wrong to any? And do not they deny the world and its pleasures, and forsake all iniquity more than yourselves?"27

Except for the bitter enemies of the Quakers, most historians have tended to render a quite favorable verdict upon the moral and ethical character of the movement. A century after the death of Fox, Clarkson could still observe that Quakerism was "a most strict profession of practical virtue under the direction of Christianity."28 Perhaps the best known estimate of a modern writer is that of William James, who said, "The Quaker religion which he [George Fox] founded is something which it is impossible to overpraise. In a day of shams, it was a religion of veracity rooted in spiritual inwardness, and a return to something more like the original gospel truth than men had ever known in England."29

During the early days of Christianity, Stoic philosophers were puzzled by the fact that ordinary men and women who became Christians lived the life of self-discipline and rigid moral purity that the Stoics believed was possible only to philosophers who had carefully disciplined the body to obey the dictates of the mind. The pagan philosophers, noble as they were in their own morality, did not grasp the nature of the moral and ethical dynamic which made early Christianity a paean of triumph over sin. "Christ liveth in me,"30 Paul declared, and John asserted the normal consequence of the indwelling Christ to be a state of genuine purity: "Whosoever abideth in him sinneth not."31 Like the first Christians, the early Quakers had found the secret of a victorious life, a secret shared alike by people of low and high degree. Penn, scholar and son of an admiral, was no greater in spiritual power than Fox, the uncultured son of a weaver.

The advocates of religion universally claim that religious faith aids in the development of morality, but the absolutism of the Friends went much beyond such moral relativisms. Instead of believing that religion merely improves the moral nature by restraining sin somewhat, they insisted that the radical surgery of the Light within had resulted in a complete victory over sin and moral darkness. Christ was the victor over the tempter, and sin had been completely defeated.

Concerning the Journal of John Woolman, Vida Scudder writes, "Purity is the central word of the Journal."32 The same observation may well be made of early Quaker writings, especially those of Isaac Penington. Purity was almost an obsession with him. The Christian life could leave no place at all for any sin. The absoluteness of his demand brooks no compromise: "Stay not in any part of the unclean land, oh child of the pure life. … If thou wilt have the pure life, both within and without, thou must part with the corrupt life, both within and without."33 The redemption of the Light was no partial or relative change for him - Christ within meant the defeat of all sin and impurity.

This insistence upon purity of life resulted in a sharp controversy between Quakers and their contemporaries on the question of how a man is justified, or accepted, by God and given entrance to heaven. Others believed that man himself can never be so perfectly righteous as to merit the approval of God, and that the only way man, necessarily and inevitably sinful, can gain access to heaven is by receiving through faith the imputed righteousness of Christ. Cloaked by this purity of Christ, yet still sinful in nature, the Puritans taught that man is justified by God. Against this teaching the early Friends unanimously and vigorously set themselves. Fox insisted, "Men are not presented to God while they do evil and before they are sanctified and holy."34 And again he says, "Such as have Christ in them, have the righteousness itself, without imputation, the end of imputation, the righteousness of God itself, Christ Jesus."35 In the thought of these early Friends, actual and complete purity is essential. Redemption is not a forensic process that takes place outside of a person. Though they never denied the historical Jesus and his atoning work, they insisted that such atonement was meaningless unless it accomplished a perfect work in purifying and cleansing the soul. Both the Quakers and their opponents agreed that the atonement took away the guilt of sins, but the Friends went to the extreme of insisting that redemption took away the sins also.

In fairness to the Quakers, it should be stated that sin was interpreted as conscious disobedience to what was believed to be the will of God. Thus a man might fall far short of the absolute perfection of God, but this lack of perfect knowledge and wisdom need not keep him from perfectly obeying whatever measure of truth is a present possession. Even if a person is in actual error in judgment, his action does not become sinful until he knows that his judgment is wrong. Although Fox made some extreme claims of absolute infallibility, other Friends were unwilling to join in such assertions. They generally recognized the possibility of errors in judgment, but they believed that God did not attach guilt to a wrong that was done unintentionally.

The true content of the redemption claimed by the "children of Light" is best seen in the concrete descriptions that they gave of the pure life. Here the Quaker way of life makes vivid and clear what a life free of sin meant to them. The testimonies become luminous with meaning as they are seen to be the result of a serious and sustained attempt to follow the Light within to its logical conclusions in even the smallest details of life. In fact, the actual extent of this demand for absolute purity is best observed in those seemingly insignificant and trivial actions which often cost the early Friends so dearly. Although we find it difficult always to apply the same logic to ourselves, we may observe in the trials and sufferings of the despised sect that we are studying a remarkable consistency in the attempt to cast all known sin out of their lives.

The testimony against honoring men made the Friends refuse to perform the commonly accepted courtesy of taking off one's hat in the presence of a superior. Though they were counted as rude and ill-mannered, they rigidly refused to give such honor, because they believed honoring men was sinful. The same reasoning was back of their consistent use of the plain language. Small detail though it was, they regarded it as of great importance simply because any sin could not be tolerated by them.

The Quaker refusal of the oath is another example of this unbending insistence upon purity. Even those who approved of the principle found it difficult to understand why a person would be willing to spend months or even years in prison because of so small a matter. Such well-intentioned people completely missed the mark in understanding the movement. The moral absolutism of early Quakerism, applied to the renunciation of all sin, great or small, could not allow for the slightest deviation from the standard of complete purity. This attitude of refusal to compromise at all prompted Cromwell's famous remark about the Friends: "Now I see there is a people risen that I cannot win with gifts or honours, offices or places; but all other sects and people I can."36

Even Puritans did not equal the stern simplicity of life characteristic of the Quakers. Early in his youth George Fox determined that he would not eat and drink for pleasure but only for health and strength. Applied with a thoroughness which approached the rigours of monasticism, this principle made the slightest detail of habits of life matters of major concern. Our modern tendency to order our lives primarily to allow for enjoyment makes it difficult for us to understand such an attitude. The difference between us and our forebears may be easily observed in our reaction to Penn's denunciation of the theater: "Their usual entertainment is some stories fetched from the more approved romances; some strange adventures, some passionate amours, unkind refusals, grand impediments, importunate addresses, miserable disappointments, wonderful surprises, unexpected encounters, castles surprised, imprisoned lovers rescued, and meetings of supposed dead ones; bloody duels, languishing voices echoing from solitary graves, overheard mournful complaints, deep-fetched sighs sent from wild deserts, intrigues managed with unheard-of subtlety; and whilst all things seem at the greatest distance, then are dead people alive, enemies friends, despair turned to enjoyment, and all their impossibilities reconciled."37 Instead of such a way of spending time, Penn and the other Quakers recommended hard work, attending religious meetings, helping the needy, and serious study. To live "as ever in his great Taskmaster's eye" was Milton's concept of Puritanism, but even such sober morality hardly equaled Quaker ethics.

A more easily understood part of early Quakerism's attempt to live without sin is to be found in the peace testimony of the movement. Our modern objection to war is usually based on our refusal to take human life. While such an approach is harmonious with their principles, the seventeenth century Friends did not at all make this the basis of their objection to war. In fact, such a basis for pacifism is scarcely to be found in early Quaker writings. The true nature of their objection to war was rather in the insistence that war cannot be fought without an accompaniment of sinful, immoral attitudes. Because they believed they lived above all sin, they repudiated war. This principle is clearly seen in the classic answer Fox gave to those who asked him to fight: "I told them I knew from whence all wars arose, even from the lusts according to James's doctrine; and that I lived in the virtue of that life and power that took away the occasion of all wars."38

The close correlation between sin and war may further be observed in Barclay's statements on the subject. In harmony with all early Friends, he taught that war is normal under some circumstances for all those who still include sin in their lives. Comparing them with the perfect standard of pure Christianity, he says. "The present confessors of the Christian name, who are yet in the mixture [of sin and purity], and not in the patient suffering spirit, are not yet fitted for this form of Christianity, and therefore cannot be undefending themselves until they attain that perfection. But for such whom Christ has brought hither, it is not lawful to defend themselves by arms, but they ought over all to trust to the Lord."39 Clearly, he expects that only those who are purified of sin should even attempt to be pacifists, but just as clearly, he expects all who are free of guilt and sin to put war aside.

Searching questions on this basis may be asked of modern pacifists and Quakers. Do those who claim the right to be pacifists show forth consistently in their own lives, even in small details, the virtue of that life and power that took away the occasion of all wars for Fox? Word from Civilian Public Service Camps is not encouraging on this point. But do those of us who live more normal lives evidence the high standard of purity for which the early Friends asked? Does our pacifism issue from genuine purity of life, or are there attitudes and actions in our lives which are actually consistent with war? We have asked ourselves why more Quakers are not pacifists; perhaps we should ask ourselves why more of our number do not live the kind of life in which there clearly would be no place for war. Pacifism is not a cloak which is suddenly put on; rather, it is the natural product of a Christlike life. The very fact that so many of our number can participate in war is damning evidence that our whole level of life is dangerously low. Our acceptance of war is the symptom of a sadly lowered spiritual and moral vitality. If we were as genuinely Christian as early Quakerism demanded that its members be, we would know that acceptance of war simply cannot be harmonized with the perfect light of Christ.

Permeating every application of the Quaker testimonies was the belief that nothing less than the Light of Christ had given both the knowledge of how every detail of life should be lived and also the power to execute perfectly the commands of God. Quakerism in its origin was an amazingly consistent attempt to realize here on earth in mundane affairs the actual presence of God. With a daring almost incomprehensible to their contemporaries, and to us today, they honestly believed that God was incarnated in them; as Jesus had been filled with divine light and power, so were they to be filled until all of life became a glorified experience of God. They believed with profound intensity in the power of the Light within to redeem them completely from darkness and sin. God had become a living part of them. Because of this revelation of His perfect light, they believed that every aspect of life should and could be brought into harmony with the divine pattern.

The Result of Redemption

Perfect obedience to the Light normally results in a relationship with God which can be described only in mystical terms. If the Light within is truly from God, then the one who obeys it utterly and entirely should experience the relationship of communion and fellowship with God which the saints in all ages have endeavored to describe. Gone now is the sense of inner tension, the lack of unity which characterizes one who has not surrendered himself to the Light. He who has yielded himself to God in holy obedience knows in humility that this redemption has made him into a true child of God, heir and joint-heir with Christ in all the purity and power of divine love.

In spite of the literary weaknesses of most of the early Quakers, their descriptions of this experience of unity with God ring with the air of sincerity and personal experience. Common men and women though they were, they lived in the same high inspiration that the great souls of the past had known. These Friends knew that God dwelt with them and, in the joy of that experience, they gladly yielded up their whole lives in sacrifice to Him. Even in the midst of the terrible ordeals which they suffered at the hands of their enemies there came to them a peace and joy utterly indescribable.

No value that the world offered could possibly compare to the "pearl of great price" which they had discovered in this living relationship of unity and fellowship with God. Their lives were in harmony with Christ, sin had been purged, and they had been filled with overwhelming divine power and love.

The experience of the Light within, the early Friends believed, meant unity not only with God, but also with each other on basic questions of human conduct. To Fox it was unthinkable that the Light would lead one person to fight and another person to choose the paths of peace. Nor could it lead one person to hate and another to love. The Light must be the same in all men, and the presence of differences meant that the Light had not been truly followed. Individuals were to be entirely free to follow the Light within, but if they were obedient it must inevitably lead to the same conclusion for all. A high degree of divine totalitarianism was the normal result of such a belief. This expressed itself most of all in the Friends' meetings for business. Decisions were to be reached, not on the basis of voting, but rather by finding God's will, which must of necessity be the same for all. Basic differences in opinion were, therefore, evidence that God's will had not been found, that someone was not following the Light.

Guided by democratic individualism, we hesitate to follow the leading of the early Friends at this point. On the issue of war and peace, we reluctantly accept a divided meeting as an inevitable fact. Is it because we lack faith that the Light can truly lead us into unity? Do we believe that the Light has more than one answer to this problem which all men face? Or are we unwilling to demand that people be utterly obedient to the Light? Why is our Society at war with itself on one of the most basic questions of our day? Either the Light does not lead into unity, or we have not been truly obedient. Surely the message of early Friends has not been understood and practiced by us, or our Society would not today be in its present condition of disunity and division.

Obedience to the Light meant not only fellowship with God and unity among Friends, but it also meant fellowship with each other. This experience became concrete in the sharing of personal property with those in need. The Meeting for Sufferings - the first organization in early Quakerism - was a practical expression of this rebirth of the early Christian spirit of brotherhood. The manner in which misunderstandings and disagreements were handled was a living testimony to the power of love to rise above human frailties. Redemption for these people meant a state of love and unity with each other which has been surpassed few times in human history.

Our Response to the Light

The message of this lecture cannot claim for itself any great degree of originality. The interpretation of early Quakerism as a perfectionistic movement has been suggested before by William Comfort in his study booklet, Quaker Trends for Modern Friends, and many others, headed by Rufus Jones, have emphasized the importance of the Light in the thought and experience of the first Quakers. Truth is seldom new, but its value does not lie in its freshness. Rather, truth acquires its significance when it is practiced.

The implementation of this basic Quaker principle of divine indwelling in man is my concern. Knowledge about the Light is not enough. What Thomas Kelly called "holy obedience" is essential for a rejuvenation of our Society. We know that the principles of our faith teach that we can be filled with the same life and power and spirit that produced the prophets and saints of the past, but that knowledge has not made prophets and saints out of us. God waits for us to add to that knowledge the willingness to obey the Light consistently and completely.

Fearful lest we become extreme in our religion, we have hesitated to follow the radical example set by the early Friends. We prefer to be as moderate in our religion as we are respectable in our sins. But the essence of Christianity and Quakerism will never be captured by those who are unwilling to he extreme in their devotion to God. "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, with all thy soul and with all thy mind."40 Only those who practice a dedication to God so absolute that every detail of life is harmonized with the perfect teaching of the Light can know the transforming, dynamic moral and spiritual power that was discovered by George Fox.

Athanasius taught that Christ was made human in order that men might be made divine. God waits now for some group to become a divine laboratory where the Light may engage in experiments in bringing heaven to men. As men in Civilian Public Service become human guinea pigs, seeking thereby to reduce human sufferings, so ought those who take Quakerism seriously to become living experiments in God's laboratory, willing for His spirit to remould them until the pattern of divine perfection is imprinted upon their lives. All of the equipment which God needs is ready - He waits only for our consent to share in the experiment. Divinity resident within man! Do you dare to conceive what it might mean in your life if you should give yourself in abandonment to this holy experiment of God's invading love in man? Can you dream of the results if even a part of the young Friends here today were to become such a laboratory for the Light? The unlocking of cosmic power and love can be accomplished if you will become utterly, completely obedient to the Light within you. All eternity is met in you as Christ asks you to become a partner with Him in the historic task of the redemption of our world from the ocean of darkness that claims it to the ocean of God's dazzling, blinding light of divine love and perfection.

Notes:

1. Romans 7:19.

2. Augustine, The Confessions of St. Augustine, Harvard Classics Edition, 1909, page 137.

3. Penington, Isaac, The Works of Isaac Penington, 1861, Volume I, pages 191-192.

4. Fox, George, The Works of George Fox, 1831, Volume I, page 76.

5. Romans 3:23.

6. Fox, Works, Volume I, page 90.

7. Ibid., page 80.

8. Ibid., page 287.

9. Quoted in Rufus Jones' Spiritual Reformers in the 16th and 17th Centuries, 1914, page 244.

10. Fox, Works, Volume I, page 80.

11. Ibid., page 70.

12. Ibid., page 74. 13.

13. Ibid., page 75.

14. Penington, Works, Volume IV, page 78.

15. Fox, Works, Volume III, page 24.

16. Penn, William, No Cross, No Crown, 1857, 23 ed., page 217.

17. Jeremiah 8:11.

18. Genesis 1:27.

19. Augustine, The Confessions of St. Augustine, page 5.

20. John 4:14.

21. Answer 35.

22. Penington, Works, Volume I, page 9.

23. Fox, G., Volume VI, page 171.

24. Flew, R. Newton, The Idea of Perfection in Christian Theology, 1934, page 290.

25. II Corinthians 5:17.

26. Fox, Works. Volume I, page 84.

27. Ibid., Volume III, page 24.

28. Clarkson, Thomas, A Portraiture of Quakerism, 1870, pages 1-2.

29. James, William, The Varieties of Religious Experiences, 1902, page 7.

30. Galatians 2:20.

31. I John 3:6.

32. Woolman, John, The Journal and Other Writings, 1936, Introduction, page 10.

33. Penington, Works, Volume I, page 228.

34. Fox, Works, Volume III, page 114.

35. Ibid., page 305.

36. Ibid., Volume I, page 210.

37. Penn, William, No Cross, No Crown, page 223.

38. Fox, Works. Volume I, page 173.

39. Barclay, Robert, An Apology for the True Christian Divinity, 1908, page 537.

40. Matthew 22:37.

Thought for the Week: Jennifer Kavanagh re-reads Thomas Kelly | The Friend

Thought for the Week: Jennifer Kavanagh re-reads Thomas Kelly

6 Jan 2022 | by Jennifer Kavanagh

‘It is in the power of community that we can most effectively express our faith.’

‘Does our discomfort stem from some level of recognition?’ | Photo: Thomas R. Kelly, in 1914

‘Does our discomfort stem from some level of recognition?’ | Photo: Thomas R. Kelly, in 1914I have been re-reading the American Quaker, Thomas Kelly. Not the much-loved A Testament of Devotion but the less familiar The Eternal Promise, a series of essays written between 1936 and 1940. Writing in a world on the edge and in the early days of war, Kelly knew well what it is to live in hard times. Even if his language isn’t always ours, I feel that much of what he writes about community, activism and, above all, spiritual renewal, has a strong resonance for Friends today.

Kelly is clear-eyed and uncompromising in what he says about the urgent need for spiritual renewal. He does not hold back in his criticism not only of the external religiousness of some churchgoers but of the attitude of modern Quakers. He considers that too many of us are ‘respectable, complacent, comfortable’, ‘paled-out remnants’ of the fire that kindled early Friends. He considers that many of us ‘have become as mildly and conventionally religious as were the tepid church members of three centuries ago against whose flaccid mediocrity George Fox flung himself’. Ouch! Does our discomfort stem from some level of recognition?

And this relates too to our activism, which he fears has become too secular – is not sufficiently rooted in our spiritual lives. Yes, we may be passionate in our activism but where is our passion for the ground of our action, the ground of our being?

Kelly is not asking us to retreat from the world – far from it. As a very active Quaker, serving on the American Friends Service Committee, he was acutely aware of the devastation in a war-torn world. It is to engage with that suffering that he asks us to go within, to rededicate our lives. ‘Attend to the Eternal that He may recreate you and sow you deep into the furrows of the world’s suffering.’

And it is in the power of community that we can most effectively express our faith. Kelly mourns the day when ‘the fellowship of the early Children of the Light gave way to membership in the Society of Friends’, And now that we have become not only the Society of Friends (tellingly, we usually drop the word ‘Religious’) but charities subject to ever-increasing layers of secularised bureaucracy, his concerns ring an uncomfortably loud bell. How I welcome our current movement towards a simpler Society! I hope that will mean not only a stripping away of unnecessary procedures, but what I consider the real meaning of simplicity: a focus on what matters, on our spiritual lives, on our rootedness in the Divine.

As we move into another year and consider how we can adjust to current conditions and our own hard times, maybe what we need, Friends, individually and collectively, is a spiritual renewal.

John Henry Newman - Wikipedia

John Henry Newman

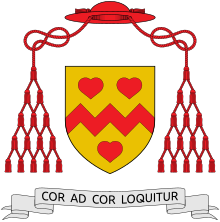

John Henry Newman | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardinal Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro | |||

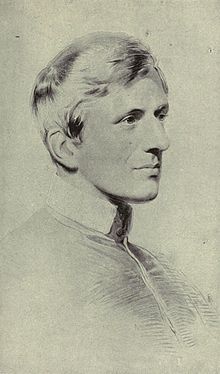

Portrait of Newman in choir dress by John Everett Millais, 1881 | |||

| Church | Catholic Church | ||

| Appointed | 15 May 1879 | ||

| Term ended | 11 August 1890 | ||

| Predecessor | Tommaso Martinelli | ||

| Successor | Francis Aidan Gasquet | ||

| Other post(s) | |||

| Orders | |||

| Ordination |

| ||

| Created cardinal | 12 May 1879 by Pope Leo XIII | ||

| Rank | Cardinal deacon | ||

| Personal details | |||

| Born | John Henry Newman 21 February 1801 | ||

| Died | 11 August 1890 (aged 89) Edgbaston, Birmingham, England | ||

| Buried | Oratory Retreat Cemetery Rednal, Metropolitan Borough of Birmingham, West Midlands, England | ||

| Nationality | British | ||

| Denomination |

| ||

| Parents |

| ||

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford | ||

| Motto | Cor ad cor loquitur ('Heart speaks unto heart') | ||

| Coat of arms |  | ||

| Sainthood | |||

| Feast day |

| ||

| Venerated in | |||

| Beatified | 19 September 2010 Cofton Park, Birmingham, England by Pope Benedict XVI | ||

| Canonized | 13 October 2019 Saint Peter's Square,[1] Vatican City by Pope Francis | ||

| Attributes | Cardinal's attire, Oratorian habit | ||

| Patronage | Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham; poets | ||

| Shrines | Birmingham Oratory | ||

Philosophy career | |||

Notable work | |||

| Era | 19th-century philosophy | ||

| Region | Western philosophy | ||

| School | |||

Main interests | |||

Notable ideas | |||

show Influences | |||

show Influenced | |||

Ordination history | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

show Variants |

show Concepts |

show Politicians |

show Organizations |

show Religious conservatism |

show National variants |

show Related topics |

John Henry Newman CO (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, scholar and poet, first an Anglican priest and later a Catholic priest and cardinal, who was an important and controversial figure in the religious history of England in the 19th century. He was known nationally by the mid-1830s,[11] and was canonised as a saint in the Catholic Church in 2019.

Originally an evangelical academic at the University of Oxford and priest in the Church of England, Newman became drawn to the high-church tradition of Anglicanism. He became one of the more notable leaders of the Oxford Movement, an influential and controversial grouping of Anglicans who wished to return to the Church of England many Catholic beliefs and liturgical rituals from before the English Reformation. In this, the movement had some success. After publishing his controversial Tract 90 in 1841, Newman later wrote: "I was on my death-bed, as regards my membership with the Anglican Church."[12] In 1845 Newman, joined by some but not all of his followers, officially left the Church of England and his teaching post at Oxford University and was received into the Catholic Church. He was quickly ordained as a priest and continued as an influential religious leader, based in Birmingham. In 1879, he was created a cardinal by Pope Leo XIII in recognition of his services to the cause of the Catholic Church in England. He was instrumental in the founding of the Catholic University of Ireland in 1854, although he had left Dublin by 1859. (The university in time evolved into University College Dublin.)[13]

Newman was also a literary figure: his major writings include the Tracts for the Times (1833–1841), his autobiography Apologia Pro Vita Sua (1865–1866), the Grammar of Assent (1870), and the poem The Dream of Gerontius (1865),[14] which was set to music in 1900 by Edward Elgar. He wrote the popular hymns "Lead, Kindly Light", "Firmly I believe, and truly", and "Praise to the Holiest in the Height" (the latter two taken from Gerontius).

Newman's beatification was proclaimed by Pope Benedict XVI on 19 September 2010 during his visit to the United Kingdom.[15] His canonisation was officially approved by Pope Francis on 12 February 2019,[16] and took place on 13 October 2019.[17] He is the fifth saint of the City of London, after Thomas Becket (born in Cheapside), Thomas More (born on Milk Street), Edmund Campion (son of a London bookseller) and Polydore Plasden (of Fleet Street).[18][19]

Contents

Early life and education[edit]

Newman was born on 21 February 1801 in the City of London,[14][20] the eldest of a family of three sons and three daughters.[21] His father, John Newman, was a banker with Ramsbottom, Newman and Company in Lombard Street. His mother, Jemima (née Fourdrinier), was descended from a notable family of Huguenot refugees in England, founded by the engraver, printer and stationer Paul Fourdrinier. Francis William Newman was a younger brother. His younger sister, Harriet Elizabeth, married Thomas Mozley, also prominent in the Oxford Movement.[22] The family lived in Southampton Street (now Southampton Place) in Bloomsbury and bought a country retreat in Ham, near Richmond, in the early 1800s.[23]

At the age of seven Newman was sent to Great Ealing School conducted by George Nicholas. There George Huxley, father of Thomas Henry Huxley, taught mathematics,[24] and the classics teacher was Walter Mayers.[25] Newman took no part in the casual school games.[26] He was a great reader of the novels of Walter Scott, then in course of publication,[27] and of Robert Southey. Aged 14, he read sceptical works by Thomas Paine, David Hume and perhaps Voltaire.[28]

Evangelical[edit]

At the age of 15, during his last year at school, Newman converted to Evangelical Christianity, an incident of which he wrote in his Apologia that it was "more certain than that I have hands or feet".[29] Almost at the same time (March 1816) the bank Ramsbottom, Newman and Co. crashed, though it paid its creditors and his father left to manage a brewery.[30] Mayers, who had himself undergone a conversion in 1814, lent Newman books from the English Calvinist tradition.[25] "It was in the autumn of 1816 that Newman fell under the influence of a definite creed and received into his intellect impressions of dogma never afterwards effaced."[27] He became an evangelical Calvinist and held the typical belief that the Pope was the antichrist under the influence of the writings of Thomas Newton,[31] as well as his reading of Joseph Milner's History of the Church of Christ.[22] Mayers is described as a moderate, Clapham Sect Calvinist,[32] and Newman read William Law as well as William Beveridge in devotional literature.[33] He also read The Force of Truth by Thomas Scott.[34]

Although to the end of his life Newman looked back on his conversion to Evangelical Christianity in 1816 as the saving of his soul, he gradually shifted away from his early Calvinism. As Eamon Duffy puts it, "He came to see Evangelicalism, with its emphasis on religious feeling and on the Reformation doctrine of justification by faith alone, as a Trojan horse for an undogmatic religious individualism that ignored the Church's role in the transmission of revealed truth, and that must lead inexorably to subjectivism and skepticism."[35]

At university[edit]

Newman's name was entered at Lincoln's Inn. He was, however, sent shortly to Trinity College, Oxford, where he studied widely. His anxiety to do well in the final schools produced the opposite result; he broke down in the examination, under Thomas Vowler Short,[27][36] and so graduated as a BA "under the line" (with a lower second class honours in Classics, and having failed classification in the Mathematical Papers).

Desiring to remain in Oxford, Newman then took private pupils and read for a fellowship at Oriel College, then "the acknowledged centre of Oxford intellectualism".[27] He was elected a fellow at Oriel on 12 April 1822. Edward Bouverie Pusey was elected a fellow of the same college in 1823.[27]

Anglican ministry[edit]

On 13 June 1824, Newman was made an Anglican deacon at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. Ten days later he preached his first sermon at Holy Trinity Church in Over Worton (near Banbury, Oxfordshire) while on a visit to his former teacher the Reverend Walter Mayers, who had been curate there since 1823.[37] On Trinity Sunday, 29 May 1825, he was ordained a priest at Christ Church Cathedral by the Bishop of Oxford, Edward Legge.[38] He became, at Pusey's suggestion, curate of St Clement's Church, Oxford. Here, for two years, he was engaged in parochial work and wrote articles on "Apollonius of Tyana", "Cicero" and "Miracles" for the Encyclopædia Metropolitana.[27]

Richard Whately and Edward Copleston, Provost of Oriel, were leaders in the group of Oriel Noetics, a group of independently thinking dons with a strong belief in free debate.[39] In 1825, at Whately's request, Newman became vice-principal of St Alban Hall, but he held this post for only one year. He attributed much of his "mental improvement"[27] and partial conquest of his shyness at this time to Whately.[27]

In 1826 Newman returned as a tutor to Oriel, and the same year Richard Hurrell Froude, described by Newman as "one of the acutest, cleverest and deepest men" he ever met, was elected fellow there.[27] The two formed a high ideal of the tutorial office as clerical and pastoral rather than secular, which led to tensions in the college. Newman assisted Whately in his popular work Elements of Logic (1826, initially for the Encyclopædia Metropolitana), and from him gained a definite idea of the Christian Church as institution:[27] "a Divine appointment, and as a substantive body, independent of the State, and endowed with rights, prerogatives and powers of its own".[22]

Newman broke with Whately in 1827 on the occasion of the re-election of Robert Peel as Member of Parliament for the university: Newman opposed Peel on personal grounds. In 1827 Newman was a preacher at Whitehall.[27]

Oxford Movement[edit]

In 1828, Newman supported and secured the election of Edward Hawkins as Provost of Oriel over John Keble. This choice, he later commented,[citation needed] produced the Oxford Movement with all its consequences. In the same year Newman was appointed vicar of St Mary's University Church, to which the benefice of Littlemore (to the south of the city of Oxford) was attached,[41] and Pusey was made Regius Professor of Hebrew.[27]

At this date, though Newman was still nominally associated with the Evangelicals, his views were gradually assuming a higher ecclesiastical tone. George Herring considers that the death of his sister Mary in January had a major impact on Newman. In the middle part of the year he worked to read the Church Fathers thoroughly.[42]

While local secretary of the Church Missionary Society, Newman circulated an anonymous letter suggesting a method by which Anglican clergy might practically oust Nonconformists from all control of the society. This resulted in his being dismissed from the post on 8 March 1830; and three months later Newman withdrew from the Bible Society, completing his move away from the low church group. In 1831–1832, Newman became the "Select Preacher" before the university.[27] In 1832 his difference with Hawkins as to the "substantially religious nature" of a college tutorship became acute and prompted his resignation.[27]

Mediterranean travels[edit]

In December 1832, Newman accompanied Archdeacon Robert Froude and his son Hurrell on a tour in southern Europe on account of the latter's health. On board the mail steamship Hermes they visited Gibraltar, Malta, the Ionian Islands and, subsequently, Sicily, Naples and Rome, where Newman made the acquaintance of Nicholas Wiseman. In a letter home he described Rome as "the most wonderful place on Earth", but the Roman Catholic Church as "polytheistic, degrading and idolatrous".[27][43]

During the course of this tour, Newman wrote most of the short poems which a year later were printed in the Lyra Apostolica. From Rome, instead of accompanying the Froudes home in April, Newman returned to Sicily alone.[27] He fell dangerously ill with gastric or typhoid fever at Leonforte, but recovered, with the conviction that God still had work for him to do in England. Newman saw this as his third providential illness. In June 1833 he left Palermo for Marseille in an orange boat, which was becalmed in the Strait of Bonifacio. Here, Newman wrote the verses "Lead, Kindly Light" which later became popular as a hymn.[44][43]

Tracts for the Times[edit]

Newman was at home again in Oxford on 9 July 1833 and, on 14 July, Keble preached at St Mary's an assize sermon on "National Apostasy", which Newman afterwards regarded as the inauguration of the Oxford Movement. In the words of Richard William Church, it was "Keble who inspired, Froude who gave the impetus, and Newman who took up the work"; but the first organisation of it was due to Hugh James Rose, editor of the British Magazine, who has been styled "the Cambridge originator of the Oxford Movement".[45] Rose met Oxford Movement figures on a visit to Oxford looking for magazine contributors, and it was in his rectory house at Hadleigh, Suffolk, that a meeting of High Church clergy was held over 25–26 July (Newman was not present, but Hurrell Froude, Arthur Philip Perceval, and William Palmer had gone to visit Rose),[46] at which it was resolved to fight for "the apostolical succession and the integrity of the Prayer Book".[45]

A few weeks later Newman started, apparently on his own initiative, the Tracts for the Times, from which the movement was subsequently named "Tractarian". Its aim was to secure for the Church of England a definite basis of doctrine and discipline. At the time the state's financial stance towards the Church of Ireland had raised the spectres of disestablishment, or an exit of high churchmen. The teaching of the tracts was supplemented by Newman's Sunday afternoon sermons at St Mary's, the influence of which, especially over the junior members of the university, was increasingly marked during a period of eight years. In 1835 Pusey joined the movement, which, so far as concerned ritual observances, was later called "Puseyite".[45] Through Francis Rivington, the tracts were published by the Rivington house in London.[47]

In 1836 the Tractarians appeared as an activist group, in united opposition to the appointment of Renn Dickson Hampden as Regius Professor of Divinity. Hampden's 1832 Bampton Lectures, in the preparation of which Joseph Blanco White assisted, were suspected of heresy; and this suspicion was accentuated by a pamphlet put forth by Newman, Elucidations of Dr Hampden's Theological Statements.[45]

At this date Newman became editor of the British Critic. He also gave courses of lectures in a side chapel of St Mary's in defence of the via media ("middle way") of Anglicanism between Roman Catholicism and popular Protestantism.[45]

Doubts and opposition[edit]

Newman's influence in Oxford was supreme about the year 1839.[45] Just then, however, his study of monophysitism caused him to doubt whether Anglican theology was consistent with the principles of ecclesiastical authority which he had come to accept. He read Nicholas Wiseman's article in the Dublin Review on "The Anglican Claim", which quoted Augustine of Hippo against the Donatists, "securus judicat orbis terrarum" ("the verdict of the world is conclusive").[45] Newman later wrote of his reaction:

For a mere sentence, the words of St Augustine struck me with a power which I never had felt from any words before. ...They were like the 'Tolle, lege,—Tolle, lege,' of the child, which converted St Augustine himself. 'Securus judicat orbis terrarum!' By those great words of the ancient Father, interpreting and summing up the long and varied course of ecclesiastical history, the theology of the Via Media was absolutely pulverised. (Apologia, part 5)

After a furore in which the eccentric John Brande Morris preached for him in St Mary's in September 1839, Newman began to think of moving away from Oxford. One plan that surfaced was to set up a religious community in Littlemore, outside the city of Oxford.[48] Since accepting his post at St. Mary's, Newman had a chapel (dedicated to Sts. Nicholas and Mary) and school built in the parish's neglected area. Newman's mother had laid the foundation stone in 1835, based on a half-acre plot and £100 given by Oriel College.[49] Newman planned to appoint Charles Pourtales Golightly, an Oriel man, as curate at Littlemore in 1836. However, Golightly had taken offence at one of Newman's sermons, and joined a group of aggressive anti-Catholics.[50] Thus, Isaac Williams became Littlemore's curate instead, succeeded by John Rouse Bloxam from 1837 to 1840, during which the school opened.[41][51] William John Copeland acted as curate from 1840.[52]

Newman continued as a High Anglican controversialist until 1841, when he published Tract 90, which proved the last of the series. This detailed examination of the Thirty-Nine Articles suggested that their framers directed their negations not against Catholicism's authorised creed, but only against popular errors and exaggerations. Though this was not altogether new, Archibald Campbell Tait, with three other senior tutors, denounced it as "suggesting and opening a way by which men might violate their solemn engagements to the university".[45] Other heads of houses and others in authority joined in the alarm. At the request of Richard Bagot, the Bishop of Oxford, the publication of the Tracts came to an end.[45]

Retreat to Littlemore[edit]

Newman also resigned the editorship of the British Critic and was thenceforth, as he later described it, "on his deathbed as regards membership with the Anglican Church". He now considered the position of Anglicans to be similar to that of the semi-Arians in the Arian controversy. The joint Anglican-Lutheran bishopric set up in Jerusalem was to him further evidence that the Church of England was not apostolic.[45][53]

In 1842 Newman withdrew to Littlemore with a small band of followers, and lived in semi-monastic conditions.[45] The first to join him there was John Dobree Dalgairns.[54] Others were William Lockhart on the advice of Henry Manning,[55] Ambrose St John in 1843,[56] Frederick Oakeley and Albany James Christie in 1845.[57][58] The group adapted buildings in what is now College Lane, Littlemore, opposite the inn, including stables and a granary for stage coaches. Newman called it "the house of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Littlemore" (now Newman College).[59] This "Anglican monastery" attracted publicity, and much curiosity in Oxford, which Newman tried to downplay, but some nicknamed it Newmanooth (from Maynooth College).[60] Some Newman disciples wrote about English saints, while Newman himself worked to complete an Essay on the development of doctrine.[45]

In February 1843, Newman published, as an advertisement in the Oxford Conservative Journal, an anonymous but otherwise formal retractation of all the hard things he had said against Roman Catholicism. Lockhart became the first in the group to convert formally to Catholicism. Newman preached his last Anglican sermon at Littlemore, the valedictory "The parting of friends" on 25 September, and resigned the living of St Mary's,[45] although he did not leave Littlemore for two more years, until his own formal reception into the Catholic Church.[45][41]

Conversion to Catholicism[edit]

An interval of two years then elapsed before Newman was received into the Catholic Church on 9 October 1845 by Dominic Barberi, an Italian Passionist, at the college in Littlemore.[45] The personal consequences for Newman of his conversion were great: he suffered broken relationships with family and friends, attitudes to him within his Oxford circle becoming polarised.[61] The effect on the wider Tractarian movement is still debated, since Newman's leading role is regarded by some scholars as overstated, as is Oxford's domination of the movement as a whole. Tractarian writings had a wide and continuing circulation after 1845, well beyond the range of personal contacts with the main Oxford figures, and Tractarian clergy continued to be recruited into the Church of England in numbers.[62]

Oratorian[edit]

In February 1846, Newman left Oxford for St. Mary's College, Oscott, where Nicholas Wiseman, then vicar-apostolic of the Midland district, resided; and in October he went to Rome, where he was ordained priest by Cardinal Giacomo Filippo Fransoni and awarded the degree of Doctor of Divinity by Pope Pius IX. At the close of 1847, Newman returned to England as an Oratorian and resided first at Maryvale (near Old Oscott, now the site of Maryvale Institute, a college of Theology, Philosophy and Religious Education); then at St Wilfrid's College, Cheadle; and then at St Anne's, Alcester Street, Birmingham. Finally he settled at Edgbaston, where spacious premises were built for the community, and where (except for four years in Ireland) he lived a secluded life for nearly forty years.[45]

Before the house at Edgbaston was occupied, Newman established the London Oratory, with Father Frederick William Faber as its superior.[45]

Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England[edit]

Anti-Catholicism had been central to British culture since the 16th-century English Reformation. According to D. G. Paz, anti-Catholicism was "an integral part of what it meant to be a Victorian".[63] Popular anti-Catholic feeling ran high at this time, partly in consequence of the papal bull Universalis Ecclesiae by which Pope Pius IX re-established the Catholic diocesan hierarchy in England on 29 September 1850. New episcopal sees were created and Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman was to be the first Archbishop of Westminster.

On 7 October, Wiseman announced the Pope's restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England in the pastoral letter From out of the Flaminian Gate.

Led by The Times and Punch, the British press saw this as being an attempt by the papacy to reclaim jurisdiction over England. This was dubbed the "Papal Aggression". The prime minister, John Russell, wrote a public letter to the Bishop of Durham and denounced this "attempt to impose a foreign yoke upon our minds and consciences".[64] Russell's stirring up of anti-Catholicism led to a national outcry. This "No Popery" uproar led to violence with Catholic priests being pelted in the streets and Catholic churches being attacked.

Newman was keen for lay people to be at the forefront of any public apologetics, writing that Catholics should "make the excuse of this persecution for getting up a great organization, going round the towns giving lectures, or making speeches".[65] He supported John Capes in the committee he was organising for public lectures in February 1851. Due to ill-health, Capes had to stop them halfway through.

Newman took the initiative and booked the Birmingham Corn Exchange for a series of public lectures. He decided to make their tone popular and provide cheap off-prints to those who attended. These lectures were his Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England[45] and they were delivered weekly, beginning on 30 June and finishing on 1 September 1851.

In total there were nine lectures:

- Protestant view of the Catholic Church

- Tradition the sustaining power of the Protestant view

- Fable the basis of the Protestant view

- True testimony insufficient for the Protestant view

- Logical inconsistency of the Protestant view

- Prejudice the life of the Protestant view

- Assumed principles of the intellectual ground of the Protestant view

- Ignorance concerning Catholics the protection of the Protestant view

- Duties of Catholics towards the Protestant view