This article is about the Greek term logos in philosophy, etc. For the term in Christianity, see Logos (Christianity). For the graphic mark, emblem, or symbol used for identification, see Logo. Logos (, ; Ancient Greek: λόγος, romanized: lógos; from λέγω, légō, lit. ''I say'') is a term in Western philosophy, psychology, rhetoric, and religion derived from a Greek word variously meaning "ground", "plea", "opinion", "expectation", "word", "speech", "account", "reason", "proportion", and "discourse".[1][2] It became a technical term in Western philosophy beginning with Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BC), who used the term for a principle of order and knowledge.[3]

Ancient Greek philosophers used the term in different ways. The sophists used the term to mean discourse. Aristotle applied the term to refer to "reasoned discourse"[4] or "the argument" in the field of rhetoric, and considered it one of the three modes of persuasion alongside ethos and pathos.[5] Pyrrhonist philosophers used the term to refer to dogmatic accounts of non-evident matters. The Stoics spoke of the logos spermatikos (the generative principle of the Universe) which foreshadows related concepts in neoplatonism.[6]

Within Hellenistic Judaism, Philo (c. 20 BC – c. 50 AD) adopted the term into Jewish philosophy.[7] Philo distinguished between logos prophorikos ("the uttered word") and the logos endiathetos ("the word remaining within").[8]

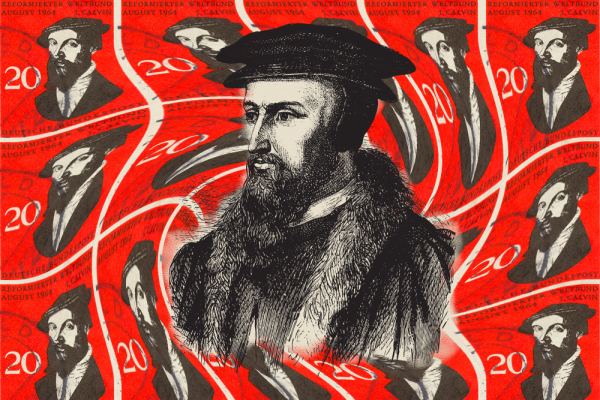

The Gospel of John identifies the Christian Logos, through which all things are made, as divine (theos),[9] and further identifies Jesus Christ as the incarnate Logos. Early translators of the Greek New Testament such as Jerome (in the 4th century AD) were frustrated by the inadequacy of any single Latin word to convey the meaning of the word logos as used to describe Jesus Christ in the Gospel of John. The Vulgate Bible usage of in principio erat verbum was thus constrained to use the (perhaps inadequate) noun verbum for "word", but later Romance language translations had the advantage of nouns such as le Verbe in French. Reformation translators took another approach. Martin Luther rejected Zeitwort (verb) in favor of Wort (word), for instance, although later commentators repeatedly turned to a more dynamic use involving the living word as felt by Jerome and Augustine.[10] The term is also used in Sufism, and the analytical psychology of Carl Jung.

Despite the conventional translation as "word", logos is not used for a word in the grammatical sense—for that, the term lexis (λέξις, léxis) was used.[11] However, both logos and lexis derive from the same verb légō (λέγω), meaning "(I) count, tell, say, speak".[1][11][12]

Ancient Greek philosophy[edit]

Heraclitus[edit]

The writing of Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BC) was the first place where the word logos was given special attention in ancient Greek philosophy,[13] although Heraclitus seems to use the word with a meaning not significantly different from the way in which it was used in ordinary Greek of his time.[14] For Heraclitus, logos provided the link between rational discourse and the world's rational structure.[15]

This logos holds always but humans always prove unable to ever understand it, both before hearing it and when they have first heard it. For though all things come to be in accordance with this logos, humans are like the inexperienced when they experience such words and deeds as I set out, distinguishing each in accordance with its nature and saying how it is. But other people fail to notice what they do when awake, just as they forget what they do while asleep.

For this reason it is necessary to follow what is common. But although the logos is common, most people live as if they had their own private understanding.

— Diels–Kranz, 22B2

Listening not to me but to the logos it is wise to agree that all things are one.

What logos means here is not certain; it may mean "reason" or "explanation" in the sense of an objective cosmic law, or it may signify nothing more than "saying" or "wisdom".[17] Yet, an independent existence of a universal logos was clearly suggested by Heraclitus.[18]

Aristotle's rhetorical logos[edit]

Following one of the other meanings of the word, Aristotle gave logos a different technical definition in the Rhetoric, using it as meaning argument from reason, one of the three modes of persuasion. The other two modes are pathos (πᾰ́θος, páthos), which refers to persuasion by means of emotional appeal, "putting the hearer into a certain frame of mind";[19] and ethos (ἦθος, êthos), persuasion through convincing listeners of one's "moral character".[19] According to Aristotle, logos relates to "the speech itself, in so far as it proves or seems to prove".[19][20] In the words of Paul Rahe:

For Aristotle, logos is something more refined than the capacity to make private feelings public: it enables the human being to perform as no other animal can; it makes it possible for him to perceive and make clear to others through reasoned discourse the difference between what is advantageous and what is harmful, between what is just and what is unjust, and between what is good and what is evil.[4]

Logos, pathos, and ethos can all be appropriate at different times.[21] Arguments from reason (logical arguments) have some advantages, namely that data are (ostensibly) difficult to manipulate, so it is harder to argue against such an argument; and such arguments make the speaker look prepared and knowledgeable to the audience, enhancing ethos.[citation needed] On the other hand, trust in the speaker—built through ethos—enhances the appeal of arguments from reason.[22]

Robert Wardy suggests that what Aristotle rejects in supporting the use of logos "is not emotional appeal per se, but rather emotional appeals that have no 'bearing on the issue', in that the pathē [πᾰ́θη, páthē] they stimulate lack, or at any rate are not shown to possess, any intrinsic connection with the point at issue—as if an advocate were to try to whip an antisemitic audience into a fury because the accused is Jewish; or as if another in drumming up support for a politician were to exploit his listeners's reverential feelings for the politician's ancestors".[23]

Aristotle comments on the three modes by stating:

Of the modes of persuasion furnished by the spoken word there are three kinds.

The first kind depends on the personal character of the speaker;

the second on putting the audience into a certain frame of mind;

the third on the proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself.

[24]

Pyrrhonists[edit]

The Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus defined the Pyrrhonist usage of logos as "When we say 'To every logos an equal logos is opposed,' by 'every logos' we mean 'every logos that has been considered by us,' and we use 'logos' not in its ordinary sense but for that which establishes something dogmatically, that is to say, concerning the non-evident, and which establishes it in any way at all, not necessarily by means of premises and conclusion."[25]

Stoic philosophy began with Zeno of Citium c. 300 BC, in which the logos was the active reason pervading and animating the Universe. It was conceived as material and is usually identified with God or Nature. The Stoics also referred to the seminal logos ("logos spermatikos"), or the law of generation in the Universe, which was the principle of the active reason working in inanimate matter. Humans, too, each possess a portion of the divine logos.[26]

The Stoics took all activity to imply a logos or spiritual principle. As the operative principle of the world, the logos was anima mundi to them, a concept which later influenced Philo of Alexandria, although he derived the contents of the term from Plato.[27] In his Introduction to the 1964 edition of Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, the Anglican priest Maxwell Staniforth wrote that "Logos ... had long been one of the leading terms of Stoicism, chosen originally for the purpose of explaining how deity came into relation with the universe".[28]

Isocrates' logos[edit]

Public discourse on ancient Greek rhetoric has historically emphasized Aristotle's appeals to logos, pathos, and ethos, while less attention has been directed to Isocrates' teachings about philosophy and logos,[29] and their partnership in generating an ethical, mindful polis. Isocrates does not provide a single definition of logos in his work, but Isocratean logos characteristically focuses on speech, reason, and civic discourse.[29] He was concerned with establishing the "common good" of Athenian citizens, which he believed could be achieved through the pursuit of philosophy and the application of logos.[29]

In Hellenistic Judaism[edit]

Philo of Alexandria[edit]

Philo (c. 20 BC – c. 50 AD), a Hellenized Jew, used the term logos to mean an intermediary divine being or demiurge.[7] Philo followed the Platonic distinction between imperfect matter and perfect Form, and therefore intermediary beings were necessary to bridge the enormous gap between God and the material world.[30] The logos was the highest of these intermediary beings, and was called by Philo "the first-born of God".[30] Philo also wrote that "the Logos of the living God is the bond of everything, holding all things together and binding all the parts, and prevents them from being dissolved and separated".[31]

Plato's Theory of Forms was located within the logos, but the logos also acted on behalf of God in the physical world.[30] In particular, the Angel of the Lord in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) was identified with the logos by Philo, who also said that the logos was God's instrument in the creation of the Universe.[30]

Neoplatonism[edit]

Neoplatonist philosophers such as Plotinus (c. 204/5 – 270 AD) used logos in ways that drew on Plato and the Stoics,[32] but the term logos was interpreted in different ways throughout Neoplatonism, and similarities to Philo's concept of logos appear to be accidental.[33] The logos was a key element in the meditations of Plotinus[34] regarded as the first neoplatonist. Plotinus referred back to Heraclitus and as far back as Thales[35] in interpreting logos as the principle of meditation, existing as the interrelationship between the hypostases—the soul, the intellect (nous), and the One.[36]

Plotinus used a trinity concept that consisted of "The One", the "Spirit", and "Soul". The comparison with the Christian Trinity is inescapable, but for Plotinus these were not equal and "The One" was at the highest level, with the "Soul" at the lowest.[37] For Plotinus, the relationship between the three elements of his trinity is conducted by the outpouring of logos from the higher principle, and eros (loving) upward from the lower principle.[38] Plotinus relied heavily on the concept of logos, but no explicit references to Christian thought can be found in his works, although there are significant traces of them in his doctrine.[citation needed] Plotinus specifically avoided using the term logos to refer to the second person of his trinity.[39] However, Plotinus influenced Gaius Marius Victorinus, who then influenced Augustine of Hippo.[40] Centuries later, Carl Jung acknowledged the influence of Plotinus in his writings.[41]

Victorinus differentiated between the logos interior to God and the logos related to the world by creation and salvation.[42]

Augustine of Hippo, often seen as the father of medieval philosophy, was also greatly influenced by Plato and is famous for his re-interpretation of Aristotle and Plato in the light of early Christian thought.[43] A young Augustine experimented with, but failed to achieve ecstasy using the meditations of Plotinus.[44] In his Confessions, Augustine described logos as the Divine Eternal Word,[45] by which he, in part, was able to motivate the early Christian thought throughout the Hellenized world (of which the Latin speaking West was a part)[46] Augustine's logos had taken body in Christ, the man in whom the logos (i.e. veritas or sapientia) was present as in no other man.[47]

The concept of the logos also exists in Islam, where it was definitively articulated primarily in the writings of the classical Sunni mystics and Islamic philosophers, as well as by certain Shi'a thinkers, during the Islamic Golden Age.[48][49] In Sunni Islam, the concept of the logos has been given many different names by the denomination's metaphysicians, mystics, and philosophers, including ʿaql ("Intellect"), al-insān al-kāmil ("Universal Man"), kalimat Allāh ("Word of God"), haqīqa muḥammadiyya ("The Muhammadan Reality"), and nūr muḥammadī ("The Muhammadan Light").

One of the names given to a concept very much like the Christian Logos by the classical Muslim metaphysicians is ʿaql, which is the "Arabic equivalent to the Greek νοῦς (intellect)."[49] In the writings of the Islamic neoplatonist philosophers, such as al-Farabi (c. 872 – c. 950 AD) and Avicenna (d. 1037),[49] the idea of the ʿaql was presented in a manner that both resembled "the late Greek doctrine" and, likewise, "corresponded in many respects to the Logos Christology."[49]

The concept of logos in Sufism is used to relate the "Uncreated" (God) to the "Created" (humanity). In Sufism, for the Deist, no contact between man and God can be possible without the logos. The logos is everywhere and always the same, but its personification is "unique" within each region. Jesus and Muhammad are seen as the personifications of the logos, and this is what enables them to speak in such absolute terms.[50][51]

One of the boldest and most radical attempts to reformulate the neoplatonic concepts into Sufism arose with the philosopher Ibn Arabi, who traveled widely in Spain and North Africa. His concepts were expressed in two major works The Ringstones of Wisdom (Fusus al-Hikam) and The Meccan Illuminations (Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya). To Ibn Arabi, every prophet corresponds to a reality which he called a logos (Kalimah), as an aspect of the unique divine being. In his view the divine being would have for ever remained hidden, had it not been for the prophets, with logos providing the link between man and divinity.[52]

Ibn Arabi seems to have adopted his version of the logos concept from neoplatonic and Christian sources,[53] although (writing in Arabic rather than Greek) he used more than twenty different terms when discussing it.[54] For Ibn Arabi, the logos or "Universal Man" was a mediating link between individual human beings and the divine essence.[55]

Other Sufi writers also show the influence of the neoplatonic logos.[56] In the 15th century Abd al-Karīm al-Jīlī introduced the Doctrine of Logos and the Perfect Man. For al-Jīlī, the "perfect man" (associated with the logos or the Prophet) has the power to assume different forms at different times and to appear in different guises.[57]

In Ottoman Sufism, Şeyh Gâlib (d. 1799) articulates Sühan (logos-Kalima) in his Hüsn ü Aşk (Beauty and Love) in parallel to Ibn Arabi's Kalima. In the romance, Sühan appears as an embodiment of Kalima as a reference to the Word of God, the Perfect Man, and the Reality of Muhammad.[58][relevant?]

Jung's analytical psychology[edit]

Carl Jung contrasted the critical and rational faculties of logos with the emotional, non-reason oriented and mythical elements of eros.[59] In Jung's approach, logos vs eros can be represented as "science vs mysticism", or "reason vs imagination" or "conscious activity vs the unconscious".[60]

For Jung, logos represented the masculine principle of rationality, in contrast to its feminine counterpart, eros:

Woman’s psychology is founded on the principle of Eros, the great binder and loosener, whereas from ancient times the ruling principle ascribed to man is Logos. The concept of Eros could be expressed in modern terms as psychic relatedness, and that of Logos as objective interest.[61]

Jung attempted to equate logos and eros, his intuitive conceptions of masculine and feminine consciousness, with the alchemical Sol and Luna. Jung commented that in a man the lunar anima and in a woman the solar animus has the greatest influence on consciousness.[62] Jung often proceeded to analyze situations in terms of "paired opposites", e.g. by using the analogy with the eastern yin and yang[63] and was also influenced by the neoplatonists.[64]

In his book Mysterium Coniunctionis Jung made some important final remarks about anima and animus:

In so far as the spirit is also a kind of "window on eternity".. it conveys to the soul a certain influx divinus... and the knowledge of a higher system of the world, wherein consists precisely its supposed animation of the soul.

And in this book Jung again emphasized that the animus compensates eros, while the anima compensates logos.[65]

Rhetoric[edit]

Author and professor Jeanne Fahnestock describes logos as a "premise". She states that, to find the reason behind a rhetor's backing of a certain position or stance, one must acknowledge the different "premises" that the rhetor applies via his or her chosen diction.[66] The rhetor's success, she argues, will come down to "certain objects of agreement...between arguer and audience". "Logos is logical appeal, and the term logic is derived from it. It is normally used to describe facts and figures that support the speaker's topic."[67] Furthermore, logos is credited with appealing to the audience's sense of logic, with the definition of "logic" being concerned with the thing as it is known.[67] Furthermore, one can appeal to this sense of logic in two ways. The first is through inductive reasoning, providing the audience with relevant examples and using them to point back to the overall statement.[68] The second is through deductive enthymeme, providing the audience with general scenarios and then indicating commonalities among them.[68]

The word logos has been used in different senses along with rhema. Both Plato and Aristotle used the term logos along with rhema to refer to sentences and propositions.[69][70]

The Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek uses the terms rhema and logos as equivalents and uses both for the Hebrew word dabar, as the Word of God.[71][72][73]

Some modern usage in Christian theology distinguishes rhema from logos (which here refers to the written scriptures) while rhema refers to the revelation received by the reader from the Holy Spirit when the Word (logos) is read,[74][75][76][77] although this distinction has been criticized.[78][79]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon: logos, 1889.

- ^ Entry λόγος at LSJ online.

- ^ Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed): Heraclitus, 1999.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Paul Anthony Rahe, Republics Ancient and Modern: The Ancien Régime in Classical Greece, University of North Carolina Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8078-4473-X, p. 21.

- ^ Rapp, Christof, "Aristotle's Rhetoric", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-8028-3634-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed): Philo Judaeus, 1999.

- ^ Adam Kamesar (2004). "The Logos Endiathetos and the Logos Prophorikos in Allegorical Interpretation: Philo and the D-Scholia to the Iliad" (PDF). Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies (GRBS). 44: 163–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-07.

- ^ May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- ^ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 460. ISBN 978-0-8028-3634-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon: lexis, 1889.

- ^ Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon: legō, 1889.

- ^ F. E. Peters, Greek Philosophical Terms, New York University Press, 1967.

- ^ W. K. C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, 1962, pp. 419ff.

- ^ The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Translations from Richard D. McKirahan, Philosophy before Socrates, Hackett, 1994.

- ^ Handboek geschiedenis van de wijsbegeerte 1, Article by Jaap Mansveld & Keimpe Algra, p. 41

- ^ W. K. C. Guthrie, The Greek Philosophers: From Thales to Aristotle, Methuen, 1967, p. 45.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Aristotle, Rhetoric, in Patricia P. Matsen, Philip B. Rollinson, and Marion Sousa, Readings from Classical Rhetoric, SIU Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8093-1592-0, p. 120.

- ^ In the translation by W. Rhys Roberts, this reads "the proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself".

- ^ Eugene Garver, Aristotle's Rhetoric: An art of character, University of Chicago Press, 1994, ISBN 0-226-28424-7, p. 114.

- ^ Garver, p. 192.

- ^ Robert Wardy, "Mighty Is the Truth and It Shall Prevail?", in Essays on Aristotle's Rhetoric, Amélie Rorty (ed), University of California Press, 1996, ISBN 0-520-20228-7, p. 64.

- ^ Translated by W. Rhys Roberts, http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/rhetoric.mb.txt (Part 2, paragraph 3)

- ^ Outlines of Pyrrhonism, Book 1, Section 27

- ^ Tripolitis, A., Religions of the Hellenistic-Roman Age, pp. 37–38. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- ^ Studies in European Philosophy, by James Lindsay, 2006, ISBN 1-4067-0173-4, p. 53

- ^ Marcus Aurelius (1964). Meditations. London: Penguin Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-14044140-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c David M. Timmerman and Edward Schiappa, Classical Greek Rhetorical Theory and the Disciplining of Discourse (London: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010): 43–66

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Volume 1, Continuum, 2003, pp. 458–62.

- ^ Philo, De Profugis, cited in Gerald Friedlander, Hellenism and Christianity, P. Vallentine, 1912, pp. 114–15.

- ^ Michael F. Wagner, Neoplatonism and Nature: Studies in Plotinus' Enneads, Volume 8 of Studies in Neoplatonism, SUNY Press, 2002, ISBN 0-7914-5271-9, pp. 116–17.

- ^ John M. Rist, Plotinus: The road to reality, Cambridge University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-521-06085-0, pp. 84–101.

- ^ Between Physics and Nous: Logos as Principle of Meditation in Plotinus, The Journal of Neoplatonic Studies, Volumes 7–8, 1999, p. 3

- ^ Handboek Geschiedenis van de Wijsbegeerte I, Article by Carlos Steel

- ^ The Journal of Neoplatonic Studies, Volumes 7–8, Institute of Global Cultural Studies, Binghamton University, 1999, p. 16

- ^ Ancient philosophy by Anthony Kenny 2007 ISBN 0-19-875272-5 p. 311

- ^ The Enneads by Plotinus, Stephen MacKenna, John M. Dillon 1991 ISBN 0-14-044520-Xp. xcii [1]

- ^ Neoplatonism in Relation to Christianityby Charles Elsee 2009 ISBN 1-116-92629-6 pp. 89–90 [2]

- ^ The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology edited by Alan Richardson, John Bowden 1983 ISBN 0-664-22748-1 p. 448 [3]

- ^ Jung and aesthetic experience by Donald H. Mayo, 1995 ISBN 0-8204-2724-1 p. 69

- ^ Theological treatises on the Trinity, by Marius Victorinus, Mary T. Clark, p. 25

- ^ Neoplatonism and Christian thought (Volume 2), By Dominic J. O'Meara, p. 39

- ^ Hans Urs von Balthasar, Christian meditation Ignatius Press ISBN 0-89870-235-6 p. 8

- ^ Confessions, Augustine, p. 130

- ^ Handboek Geschiedenis van de Wijsbegeerte I, Article by Douwe Runia

- ^ De immortalitate animae of Augustine: text, translation and commentary, By Saint Augustine (Bishop of Hippo.), C. W. Wolfskeel, introduction

- ^ Gardet, L., "Kalām", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Boer, Tj. de and Rahman, F., "ʿAḳl", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ Sufism: love & wisdom by Jean-Louis Michon, Roger Gaetani 2006 ISBN 0-941532-75-5p. 242 [4]

- ^ Sufi essays by Seyyed Hossein Nasr 1973ISBN 0-87395-233-2 p. 148]

- ^ Biographical encyclopaedia of Sufis by N. Hanif 2002 ISBN 81-7625-266-2 p. 39 [5]

- ^ Charles A. Frazee, "Ibn al-'Arabī and Spanish Mysticism of the Sixteenth Century", Numen 14 (3), Nov 1967, pp. 229–40.

- ^ Little, John T. (January 1987). "Al-Ins?N Al-K?Mil: The Perfect Man According to Ibn Al-'Arab?". The Muslim World. 77 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1987.tb02785.x.

Ibn al-'Arabi uses no less than twenty-two different terms to describe the various aspects under which this single Logos may be viewed.

- ^ Dobie, Robert J. (17 November 2009). Logos and Revelation: Ibn 'Arabi, Meister Eckhart, and Mystical Hermeneutics. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0813216775.

For Ibn Arabi, the Logos or "Universal Man" was a mediating link between individual human beings and the divine essence.

- ^ Edward Henry Whinfield, Masnavi I Ma'navi: The spiritual couplets of Maulána Jalálu-'d-Dín Muhammad Rúmí, Routledge, 2001 (originally published 1898), ISBN 0-415-24531-1, p. xxv.

- ^ Biographical encyclopaedia of Sufis by N. Hanif 2002 ISBN 81-7625-266-2 p. 98 [6]

- ^ Betül Avcı, "Character of Sühan in Şeyh Gâlib’s Romance, Hüsn ü Aşk (Beauty and Love)" Archivum Ottomanicum, 32 (2015).

- ^ C.G. Jung and the psychology of symbolic forms by Petteri Pietikäinen 2001 ISBN 951-41-0857-4 p. 22

- ^ Mythos and logos in the thought of Carl Jung by Walter A. Shelburne 1988 ISBN 0-88706-693-3 p. 4 [7]

- ^ Carl Jung, Aspects of the Feminine, Princeton University Press, 1982, p. 65, ISBN 0-7100-9522-8.

- ^ Aspects of the masculine by Carl Gustav Jung, John Beebe p. 85

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung: critical assessments by Renos K. Papadopoulos 1992 ISBN 0-415-04830-3 p. 19

- ^ See the neoplatonic section above.

- ^ The handbook of Jungian psychology: theory, practice and applications by Renos K. Papadopoulos 2006 ISBN 1-58391-147-2 p. 118 [8]

- ^ Fahnestock, Jeanne. "The Appeals: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos".

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Aristotle's Three Modes of Persuasion in Rhetoric".

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Ethos, Pathos, and Logos".

- ^ General linguistics by Francis P. Dinneen 1995 ISBN 0-87840-278-0 p. 118 [9]

- ^ The history of linguistics in Europe from Plato to 1600 by Vivien Law 2003 ISBN 0-521-56532-4 p. 29 [10]

- ^ Theological dictionary of the New Testament, Volume 1 by Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, Geoffrey William Bromiley 1985 ISBN 0-8028-2404-8 p. 508 [11]

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q-Z by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1995 ISBN 0-8028-3784-0 p. 1102 [12]

- ^ Old Testament Theology by Horst Dietrich Preuss, Leo G. Perdue 1996 ISBN 0-664-21843-1 p. 81 [13]

- ^ What Every Christian Ought to Know by Adrian Rogers 2005 ISBN 0-8054-2692-2 p. 162 [14]

- ^ The Identified Life of Christ by Joe Norvell 2006 ISBN 1-59781-294-3 p. [15]

- ^ [16] Holy Spirit, Teach Me by Brenda Boggs 2008 ISBN 1-60477-425-8 p. 80

- ^ [17] The Fight of Every Believer by Terry Law ISBN 1-57794-580-8 p. 45

- ^ James T. Draper and Kenneth Keathley, Biblical Authority, Broadman & Holman, 2001, ISBN 0-8054-2453-9, p. 113.

- ^ John F. MacArthur, Charismatic Chaos, Zondervan, 1993, ISBN 0-310-57572-9, pp. 45–46.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Logos |

Let us recall how the death of others is experienced. In the case of our family and personal friends, we rehearse our memories of them, we cherish objects associated with them. For those who have had a more general impact, we remember their works: the companies they built, the devices they invented, the treaties they signed, the books or music they composed.

Let us recall how the death of others is experienced. In the case of our family and personal friends, we rehearse our memories of them, we cherish objects associated with them. For those who have had a more general impact, we remember their works: the companies they built, the devices they invented, the treaties they signed, the books or music they composed. Where is the self in all this? Mallarmé wrote the poem quoted above for the unveiling of a monument in honor of Edgar Allan Poe. Poe was an alcoholic who had led an unhappy, dissolute life. But his death makes such facts secondary; as he lives in our memory, it is in his art that Poe is truly Lui-même. Nor is this a sentimental figure of speech; it is a matter of historical fact. Perhaps Poe himself might have preferred to survive in some other guise, but we do not memorialize the dead in answer to their wishes. The himself that history makes of him is a function of his public image. It is subject to modification, but the dead person himself is no longer in control of this modification.

Where is the self in all this? Mallarmé wrote the poem quoted above for the unveiling of a monument in honor of Edgar Allan Poe. Poe was an alcoholic who had led an unhappy, dissolute life. But his death makes such facts secondary; as he lives in our memory, it is in his art that Poe is truly Lui-même. Nor is this a sentimental figure of speech; it is a matter of historical fact. Perhaps Poe himself might have preferred to survive in some other guise, but we do not memorialize the dead in answer to their wishes. The himself that history makes of him is a function of his public image. It is subject to modification, but the dead person himself is no longer in control of this modification.