Buddhistdoor View: Conscience in the Thought of Bhikkhu Bodhi

Buddhistdoor Global | 2015-06-26 |

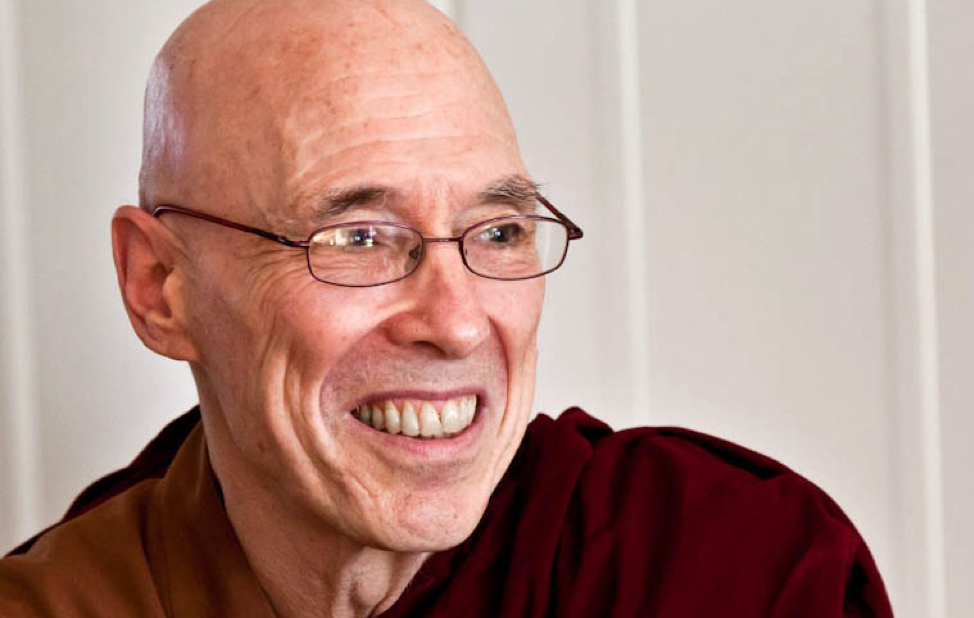

Bhikkhu Bodhi. From groups.yahoo.com

Bhikkhu Bodhi. From groups.yahoo.com Bhikkhu Bodhi at a demonstration against the Keystone XL pipeline, 2013. From buddhistglobalrelief.me

Bhikkhu Bodhi at a demonstration against the Keystone XL pipeline, 2013. From buddhistglobalrelief.me Segment of birchbark manuscript from Gandhara, 1st or 2nd century CE. From washington.edu

Segment of birchbark manuscript from Gandhara, 1st or 2nd century CE. From washington.edu Segment of birchbark manuscript from Gandhara, 1st or 2nd century CE. From the British Library.

Segment of birchbark manuscript from Gandhara, 1st or 2nd century CE. From the British Library. Continental philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer. From ymago.net

Continental philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer. From ymago.netBefore the late 2000s, Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi was not well known as an environmental activist and leader of humanitarian causes. Practitioners of the 1990s and earlier became acquainted with the American-born Theravada monk mainly through his guided meditation and recorded breathing and sitting courses. He was also renowned for his seminal translations and editorship of several major publications of Theravada texts, along with a slew of academic articles and columns too numerous to mention in great detail. His scholarly credentials influenced a variety of fields, spanning early Buddhism to Vinaya law concerning women’s ordination.

One could also have assumed that he was, as unhelpful as labels might be, a “traditionalist.” As recently as May this year, he dismissed mindfulness as the “pop-tune of the 21st century” in an interview with angel Kyodo williams on Patheos. This is not something that Western Buddhists, many of them identifying with the popular mindfulness movement, would like to hear. In the same interview, he praised cultural critic Slavoj ?i?ek’s criticism of Western Buddhism as rendering people ethically inert.

His engaged Buddhism seems to tell a more complicated story. In 2007, he founded Buddhist Global Relief, a humanitarian organization fighting to alleviate global hunger and malnutrition. In February 2014, he published an article on the website Truthout titled “Clearing Our Heads About Keystone.” His warning against building the Keystone Pipeline System is about as technical as an article on tar sands and oil engineering can be, using environmental terminology more common to activists and engineers. In August the same year, he published an article detailing the part he intended to play at the People’s Climate March that took place on 21 September. From his passionate writing, one can see a Bhikkhu Bodhi that seems quite different to his translator-meditator persona.

His two faces—the professorial scholar-translator with a PhD and the advocate of ecological and social justice—melded together in an interview for the Eastern Religions Society at the University of St Andrews in 2013, in which he suggested that a passage in the Anguttara Nikaya (4:115) provided good counsel on caring for the environment. This marriage between the traditional exegete and social activist makes him a complex thinker, to the point that labels like “traditionalist” or “liberal” no longer seem helpful.

What is one to make of a monk who believes that the Vinaya permits women’s ordination, mindfulness as it is taught is ethically and spiritually deficient, and climate change is the paramount issue facing civilization?

Clues can be found in an essay he penned in February 2013 for the website Parabola: “I feel that sometimes one must give priority to one’s deep intuitions over officially sanctioned norms, even when this causes some degree of internal friction. Looking at Buddhism as part of the spiritual heritage of humanity, I see it as subject to similar evolutionary pressures as other types of contemplative spirituality have felt,” he wrote. “As I see it, our collective future requires that we fashion an integral type of spirituality that can bridge the three domains [transcendent, social, and natural] of human life. This would entail embarking on a new trajectory.”

What seems to characterize Bhikkhu Bodhi’s thought is a union between deeply personal impulses and doctrinal fidelity. This interplay and tension is complex. However, it has helped him to offer very creative input into how a Buddhist should live. He is embracing causes that are never mentioned in the ancient canon, yet these causes do not detract from his practice. Instead, they catapult his faith into the public sphere in the form of forums, protest marches, and meetings with diverse people and interests.

His approach—“Bodhism,” one could informally call it—is not a school of thought or methodology. It is more a temperament that allows space for personal conscience to function as a hermeneutical tool (way of interpretation) for one’s faith. Bodhism suggests that our inner intuitions, as long as they are driven by right intention, can serve as guides for how we can be better Buddhists. By extension, this means that the Buddhist scriptures do not always hold the complete answers in the contemporary world. Indeed, Bodhism proposes that the living texts are beckoning Buddhists to read them in the context of their own circumstances and society.

In philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer’s words, this requires a “fusion of horizons”* (Gadamer 1997, 302). This would mean a meeting between the practitioner and the shadowy, nameless authors that revealed the Buddha’s word in the ancient Pali Canon, the early Perfection of Wisdom sutras, the Pure Land scriptures, and so many other texts. Through this meeting of text and conscience, the texts help the disciple progress in spiritual realization. Meanwhile, the scriptures, through the contemporary eyes of the practitioner, are able to have their relevance in the 21st century unpacked and articulated.

Bodhism therefore entails an imaginative and personal engagement. Bhikkhu Bodhi feels particularly drawn to environmental issues and poverty. Another Buddhist might feel an urge to act on sexism or racism. People are animated by all kinds of issues, be they broad or specific. The possibilities are as diverse as the consciences residing in the world’s seven billion human beings.

Textual authority alone can’t answer all the questions and dilemmas posed by the complex contemporary world. No single ideology or hermeneutic will be sufficient. But new insights are possible if we accept that the Buddhist texts are inviting us to use a bit of imagination. Approaches that let intuition and conscience “talk to” the tradition’s doctrines—hence forging a uniquely personal expression of Buddhism like Bhikkhu Bodhi’s—may well be the way forward.

* The fusion of horizons (Horizontverschmelzung) is a dialectical concept presenting horizons as “everything that can be seen from a particular vantage point” (Gadamer 1997, 302). In this image, our horizons are historically, linguistically, and culturally conditioned and therefore limited. Yet horizons are also by nature open, and in the hermeneutic encounter can be broadened by each other. A new understanding or fusion therefore occurs in the dialectic between a person’s horizon and the horizon of a text or tradition, with neither remaining unaffected.

References

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. (1988) 1997. Truth and Method. New York: Continuum.

See more

Clearing Our Heads About Keystone (Truthout)

Bhikkhu Bodhi on mindfulness, ethics, responsibility and justice with angel Kyodo williams (Patheos)

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi, Buddhism, and the Environment (University of St Andrews)

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Images courtesy of David Maisel/Institute

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, originally from New York City. He received novice ordination in 1972 and full ordination in 1973 and lived in Asia for 24 years, primarily in Sri Lanka. A Buddhist scholar and translator of Buddhist texts,

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, originally from New York City. He received novice ordination in 1972 and full ordination in 1973 and lived in Asia for 24 years, primarily in Sri Lanka. A Buddhist scholar and translator of Buddhist texts,