Beyond the Sprouts of Capitalism

Toward an Understanding of China’s Historical Political Economy and Its Relationship to Contemporary China

I

The contemporary political economy of the People’s Republic of China, the nature of the Chinese system, has been the subject of much discussion and debate in mainstream academic, media, and political circles, as well as on the left.1 Since the end of the 1970s, China has pursued policies of “reform and opening” (gaige kaifang, 改革開放) to develop its economy, a process that has resulted in the massive growth of production, China’s emergence as a major player in global trade, and the lifting of around 800 million people out of poverty, while at the same time generating serious problems of inequality, corruption, and environmental stress. At the heart of this project has been the decision by the Communist Party, originally under the guidance of Deng Xiaoping, then carrying on through successive changes of leadership, to use the mechanisms of the marketplace to develop the productive economy. How should this situation be characterized? Is it capitalism, state capitalism, market socialism?2

One can only make sense of contemporary China with a clear understanding of the country’s economic history.3 A historical materialist analysis of the nature of China’s political economic order over the course of history, especially the last thousand years, can illuminate critical aspects of the present. A serious engagement with the complexities of China’s historical economic systems must take into account knowledge about the Chinese past that was not available to Karl Marx, allowing us to go beyond the vagaries of the Asiatic mode of production and transcend the limitations of earlier theorizations of the “sprouts of capitalism” (ziben zhuyi de mengya, 資本注意的萌牙) by historians in China in the 1950s and ’60s.4 Applying categories and modes of analysis derived from Marx’s Capital and other writings to the understanding of China’s early modern history and exploring the relevance of that history to contemporary China are the main tasks of this essay.

From the period of the Tang-Song transition, roughly the ninth and tenth centuries, China developed a commercial capitalist economy that encompassed a largely urban manufacturing sector and also reshaped agricultural production in much of the empire. A ruling class evolved that was a hybrid of the long-established landowning elite and the early modern commercial stratum, which managed the economic affairs of the country through a blend of private agency and the operations of the imperial state. Through much of China’s imperial past, the state maintained a complex, not always consistent, role in economic affairs, seeking both to support the livelihood of the people, promote prosperity, constrain the pursuit of private profit, and regulate the functions of markets. This historical relationship has inflected the developmental itinerary of the country and is reflected in the deployment of the theory and practice of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” and the “socialist market economy.”

II

China’s recorded history goes back more than 3,200 years and can be usefully divided into four major periods: (1) antiquity, from the beginning to the end of the third century BCE; (2) the middle period, from the second century BCE to the tenth century CE; (3) the early modern period, from the tenth through the eighteenth centuries; and (4) modern China, from the end of the eighteenth century to the present.5 Throughout antiquity, China was ruled by an elite of warriors who controlled the land, collecting tribute from their subjects. Economic activity was largely locally self-sufficient, with a small layer of high-value elite trade centered on the royal court(s). Over time, a professional administrative elite developed, often referred to as the literati because of their mastery of the written records of history and their shared literary culture. These administrative officials were often rewarded with grants of land, and over time these became hereditary property, though the sovereign always retained ultimate ownership.6

The middle period began with the unification of the empire and the consolidation of the imperial system under the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE). During this period, private ownership of land became a practical reality, while in theory the empire continued to belong to the ruler, now the emperor. Many officials in government service built up significant land holdings, while other great families emerged based on their local acquisition of agricultural assets. This was a complex, long-term process, with large landed estates forming by the later Han, which became the underpinning for the political influence of the landowning class. Over the centuries of the middle period, China developed an aristocratic elite, with quasi-official status and a strong transmission of wealth across generations. China went through periods of internal division after the collapse of the Han dynasty in 220, and then renewed imperial unification under the Sui and Tang dynasties (589–618 and 618–907, respectively). Recruitment for service in the imperial government, which was largely pursued through a process of recommendation by serving officials, allowed established families to place their sons in careers in official life and perpetuate the power of the elite. This aristocratic class effectively dominated the state, which served to promote and protect its interests.7

Alongside the estates of the great families there was a sector of agricultural production organized around small holders, managed through a system of land tenure maintained by the imperial state, which regularly redistributed land to male heads of village households who, in turn, were taxed in grain and cloth products. The system varied in its specifics in different parts of the empire but was a clear example of state oversight and management of economic activity. This oversight also extended to urban centers and markets. Imperial law restricted the number and location of markets and established strict controls over their operations. This blend of aristocratic estates, state-managed distribution of small holdings, and tightly regulated urban markets was not in any sense feudal in its economic or political organization and functioning.8

By the ninth century, changes began to emerge in China’s cities and countryside. The Tang dynasty had been deeply shaken by the An Lushan Rebellion in 755–63, and the long-established aristocracy began to decline. But even before this, the very success of the imperial system of economic management had given rise to contradictions within the economy. Its potential for growth and development exceeded the parameters of state oversight, and new forces began to push beyond the regulations of the government. The power of the dominant elite and the control of urban space by official overseers weakened. Markets began to spread outside areas that had been designated and monitored by the state and to become more integrated into residential areas. Private ownership of farmland expanded beyond the great estates and the land subject to government distribution. The imperial court maintained a role in the production and distribution of certain key commodities through government monopolies, a practice that had its roots centuries earlier in the Han dynasty. But the overall role of the state in economic affairs declined, just as the class basis of imperial rule was itself dramatically altered.

In the later ninth century, further rebellions destroyed much of the elite’s wealth and the institutional infrastructure that had legitimized and maintained its power and prestige. Rebellious peasants attacked the estates of the wealthy, killed many members of the elite, and burned the documents that validated their status and power. The fall of the Tang in 907 led to the chaos of the Five Dynasties and Sixteen Kingdoms, with small regional states contending for power through chronic warfare and further destruction, until the Zhao brothers established the Song dynasty in 960 and reunified the empire over the ensuing decade. The warfare of this age of transition cleared the way for the further transformation of China’s economic and political order. The old aristocracy was gone, but the ownership of land and the control of agricultural production was still the primary mode of wealth accumulation.9

As the Song dynasty (960–1279) consolidated its power, a new elite emerged, formally based on the attainment of merit through education, but practically grounded in the riches produced on their estates. These provided the resources to support the education of sons in the Confucian classical traditions that formed the basis of the imperial civil examination system, which became the main vector for entry into service in the bureaucratic administration of the empire. Not all landowning families produced examination graduates or government officials. The class of landed wealth was more extensive than the group of literati who staffed the imperial state, and relations between members of this class in their capacity as local elites or as representatives of imperial power could be complex. This larger class is often referred to as the gentry, and the overall landowning class may be designated, perhaps somewhat awkwardly, the literati/gentry.10

This reconfiguration of the landholding elite took place in tandem with the further development of a commercial economy in China. Markets proliferated, woven together by networks of long-distance trade spanning the empire and linking up with larger global systems. New forms of capital valorization and accumulation took shape within an increasingly monetized economy. Division of labor both within productive enterprises and on a regional geographic basis, as well as ongoing technological innovation, drove enhancements in productivity. New developments in banking and financial operations facilitated the mobilization and allocation of capital.11 This is the key to understanding the early modern period that began in the ninth and tenth centuries and continued, with dramatic advances and retreats, throughout the following eight hundred years, across several dynastic transitions, down to the beginning of the modern era at the turn of the nineteenth century. It is the emergence of China’s early modern capitalist commercial economy and its development over the following years that must be understood to enable a better comprehension of China’s recent pursuit of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

III

China’s “commercial revolution” in the Song dynasty has long been recognized, beginning with the work of Naitō Konan and the Kyoto School of Marxist historians in Japan in the 1930s.12 But the intellectual constraints imposed by the orthodoxies of Soviet economic and historical thought, with the centrality of a stagist sequence of development that had to be applied to all societies around the world, meant that China could not be seen as having had a capitalist system before the arrival of European imperialism in the nineteenth century. China was either viewed as part of the Asiatic mode of production, which had remained essentially static and unchanging in a primitive form of feudalism over three millennia, or was assimilated into the succession of historical eras enshrined in Joseph Stalin’s 1938 Dialectical and Historical Materialism.13 Marx’s original formulation of the Asiatic mode of production was primarily concerned with India and was based on partial and often faulty information. His knowledge of China was severely limited by both the imperialist biases of most writers and the minimal access to Chinese-language sources available then. It is time to place China’s early modern political economy in a clearer perspective. Let us consider the organization and functioning of production and circulation in early modern China in Marxist terms.14

In volume one of Capital, Marx investigates and delineates several key features of capitalism as it had developed in Europe, most particularly in England. In his preface to the first edition, he makes clear that while he is relying primarily on the analysis of the dynamics of capital as it developed in the West, he sees the characteristics that he discerns in that context as applicable to a broader definition of capitalism as a system.15 Beginning with the commodity and commodity production—that is, production for exchange on the market—he goes on to discuss money as the universal commodity, the process of the valorization of capital (M-C-M′) based on the exploitation of labor power, the mechanisms of wage labor, the division of labor as the means of maximizing that exploitation, and the ongoing imperative of accumulation of capital. These are key defining elements of a capitalist mode of production.16

All of these are present in China from the Song dynasty on. Markets flourished and proliferated, woven together into networks of exchange that spanned the empire and linked up to larger regional and global systems. Commodity production, with sophisticated divisions of labor both across space and within enterprises, expanded dramatically. The growth of China’s capitalist system of manufacturing—which ranged from the elaborate putting-out system of the silk and cotton textile industries to the massive complex of ceramic kilns at Jingdezhen, the largest industrial center in the world before the nineteenth century—also reshaped the sphere of agricultural production.17 China had a sophisticated system of private property in land, and the buying and selling of real property was carried on and documented through the use of legally binding contracts enforceable through the imperial judicial system.18 Farming became increasingly commercialized, with production for national market distribution coming to form significant portions of production in provinces like Sichuan and Hunan. Tenant farming and agricultural day labor grew in importance. Wage and contract labor were central to the manufacturing sector in Jiangnan and elsewhere, from spinners and weavers to ceramics workers and carvers of woodblock printing boards. Strikes and other forms of labor unrest were recurrent in cities like Suzhou and Wuxi.19

China is a large and complex geographic space, with considerable variation and distinctive regional subunits, called macroregions, as theorized by G. William Skinner.20 Each of these is as large as a major European state. Early capitalism in China was by no means equally developed across the empire. Some regions, such as the northwest or the southwest, were much less commercially developed than others, such as the Jiangnan area of the Yangtze River delta, the southeast coast, the corridor along the Grand Canal, or the long valley of the Yangtze. China’s early capitalism was most highly evolved in Jiangnan, where networks of urban production and distribution facilitated sophisticated systems of capital accumulation and deployment. In European history, given the fragmentation of political authority into small and conflicting territorial spaces, the consideration of the economy of England as a discrete unit of analysis, as opposed to a larger European whole, has been the norm. Given China’s vast territorial extent and complex internal macroregional variation, the understanding of early Chinese capitalism as a distinctive formation within the overall expanse of imperial space seems like a more useful approach than attempting to fit the empire as a whole into a monolithic categorization.21

The point is not that China was just like Europe (or, more properly, the other way around, given the chronological sequence of developments), but that the fundamental attributes of capitalism, as explicated in Capital, were also present there, in their own historically and culturally specific forms. China’s early modern political economy, a distinctive form of early capitalism, emerged in the Song dynasty and persisted through periods of growth and contraction across the following Yuan and Ming eras and into the final Qing dynasty. Two aspects of this historical trajectory are of particular interest in understanding the distinctive course of development that characterized China’s early modernity in contrast to the later path of European experience. One is the span of time, which extended over some eight centuries; the other is the nature of class formation and interaction.

IV

Early modernity in China was not a linear process of development leading to a fully modern industrial economy. Early Chinese capitalism, despite going through periods of dynamic growth and transformation, remained essentially commercial capitalism at the level of manufacture, as described in chapter 14 of the first volume of Capital.22 This was a more sophisticated system of production than simple handicraft activities by individual households, but, other than in the special case of the kiln city of Jingdezhen, was not organized into large-scale industrial enterprises. Production was carried out through complicated networks of social relations, in workshops and households, while distribution was largely managed by networks of merchants spanning multiple provinces in interconnecting webs of commerce. Financial mechanisms of credit and banking facilitated long-distance trade.23 These structural features first arose in the Song dynasty and were elaborated and refined in the Ming and Qing dynasties. But the course of economic life, as of China’s history overall, was not one of smooth and tranquil progress. In the twelfth century, the Song lost control of the northern half of the empire to invaders from the northeast called the Jurchen, who established their own dynasty. In the thirteenth century, the rise of the Mongols plunged the remnant Southern Song into a decades-long war of resistance that ended in the collapse of the dynasty and the creation of the Mongol-ruled Yuan as its successor. These wars, and the often anticommercial policies of the Mongols during their century of rule, caused great destruction to China’s population and economy. The Mongols engaged in high-value international trade, but the domestic commercial economy declined during their time in power, though the most highly developed Jiangnan region seems to have fared better than other parts of the empire. When the Ming dynasty was founded in 1368, after central China had been further devastated by disease and the rebellions that overthrew the Yuan, the first emperor was actively hostile to merchant wealth and promoted a physiocratic vision of society based on small landholding and local self-sufficiency, although the empire-spanning network of roadways that he developed for imperial communications also facilitated the revival of long-distance trade.24

The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw a dramatic revival of China’s early capitalism, as production and trade across the empire flourished and the international demand for Chinese goods such as tea, porcelain, and silk and cotton textiles drew increasing amounts of silver, first from Japan and then from the mines of the Spanish New World empire via the Manila galleon trade, into China.25 Ongoing technological innovations drove improvements in productivity and quality that made Chinese manufactures ever more popular in global markets. But by the mid–seventeenth century, contradictions within Ming society and politics led to the collapse of the dynasty, and yet another invasion by a non-Chinese coalition led by the Manchus seized power and installed the Qing dynasty in 1644. In the eighteenth century, China recovered from the traumas of the dynastic transition, and a final era of early capitalist prosperity ensued.26

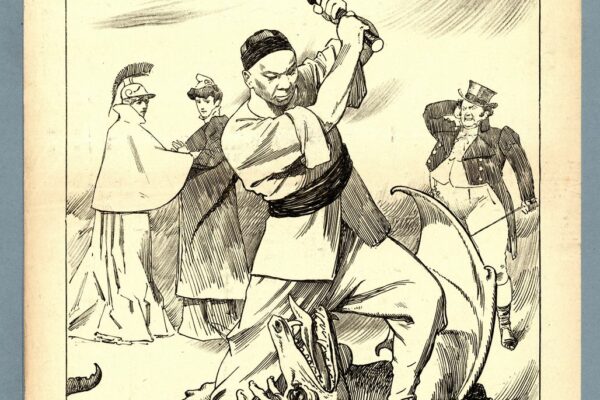

“The Opium Ban in China” poster from De Amsterdammer, December 2, 1906 (via International Institute of Social History). Rough translation of bottom caption: John Bull: “Such a heathen…as a dragon slayer! … I will feel that in my wallet!” Dutch Virgin (to Marianne): “And that this guy should give us an example ….”

In 1793, the British king George III sent a diplomatic mission to China, led by Lord George Macartney, to seek new trade relations. Foreigners were allowed to trade with China in a regulated system at the port of Guangzhou, known to Westerners as Canton, in the far south of the empire. The British, imbued with the new ideology of free trade and on the cusp of the Industrial Revolution, wanted China to open more ports and allow a permanent diplomatic presence in Beijing. The Qianlong emperor declined these requests and reminded the British, in a letter to King George, that China had all it needed within its own borders and had no wish for the inferior products of the West. But while this remained the case, a combination of domestic and international factors was about to bring an end to China’s early modern capitalist age. Limits on the capacity of agriculture to sustain continuing population growth began to erode material standards of living. The rise of England’s modern industrial economy brought both inexpensive goods to compete with China’s domestic products and the military capacity to force the Qing government to open the empire to Western imperialism. A new era was beginning.

V

Early modern capitalism in China endured across many centuries, with periods of expansion and contraction, but with a persistent drive toward greater sophistication and productivity, and with the accumulation of wealth derived from the extraction of surplus value from labor power reviving after each era of destruction. This generated a wealthy stratum of merchants and investors, largely urban in residence, and distinct from the more traditional elite of landowning households that, through their domination of the Confucian civil service examination system, controlled the operations of the imperial government. Within the discursive field of Confucian thought there was a strong tradition of aversion to commercial wealth and disrespect for those who lived on the profits of trade. Merchants and their sons (and sometimes grandsons) were legally excluded from participation in the examination system, and thus effectively from political power. With the rise of early capitalism and the emergence of a wealthy commercial elite, these ideas began to be challenged and changed by some thinkers. While merchants never came to be fully entitled to an equal role in the examination system or to a political status matching that of the literati/gentry elite, a convergence of interests drove a slow process of cultural adjustment that created a hybrid class more complex than either a purely land- or commerce-based elite. This change in attitude, in political culture, was driven by the convergent material interests and actions of both agricultural and manufacturing producers.27

As China’s economy became more differentiated, with regional specialization in the production of certain commodities and the attendant growth of long-distance trade in both manufactured goods and foodstuffs, commercialized farming became increasingly profitable and landowning families sought new ways to invest their wealth. Merchants and investors in manufacturing activities also were generating wealth and seeking to further expand the valorization and accumulation of their capital. At the same time, many members of the commercial elite sought to position themselves socially as the equals of the literati/gentry in status and prestige by engaging in patronage of religious establishments, cultural pursuits such as the collecting of art or the assembling of libraries, or the building of elaborate mansions and gardens.28

The intersection of the interests and ambitions of landowning and commercial elites came about through the process of investment in economic activities. Members of the literati/gentry elite directed some of their wealth into the businesses of merchants and manufacturers, and shared in the profits of those enterprises. These economic strategies resulted in a convergence of interests rather than a relationship of antagonism. This is in some ways a stark contrast with the later history of class conflict between the rising bourgeoisie and the older feudal aristocracy in Europe, but it is not without parallel. Indeed, in an 1850 review of a book on the seventeenth-century English Revolution by the French politician François Guizot, Marx described a similar convergence of class interests:

This class of large landowners allied with the bourgeoisie…was not, as were the French feudal landowners of 1789, in conflict with the vital interests of the bourgeoisie, but rather in complete harmony with them. Their estates were indeed not feudal but bourgeois property. On the one hand, they provided the industrial bourgeoisie with the population necessary to operate the manufacturing system, and on the other hand, they were in a position to raise agricultural development to the level corresponding to that of industry and commerce. Hence their common interests with the bourgeoisie: hence their alliance.29

The convergence of interests between the landed literati/gentry and the largely urban commercial/manufacturing elite in China persisted, and perhaps deepened, across the span of early modern times. Both sides of this ruling-class collaboration of course remained dedicated to the extraction of surplus value from the labor of workers, whether on farms, in workshops, households, or the marketplace. This hybridity was also reflected in economic thought and government policy. The imperial state was not a strong advocate for commercial interests, but nonetheless often played a role in economic life that benefitted both manufacturing and exchange. The construction and maintenance of roads and canals facilitated the growth of long-distance trade. Government intervention in some critical commodity markets, especially grain, often served to stabilize prices and buffer the extremes of market fluctuations, thus protecting both the livelihoods of consumers and the ongoing operations of merchants.30 The interplay of elite interests and state policy varied over time but was always complex and could certainly be contentious. Fundamental to China’s Confucian political culture was the idea that the state’s primary purpose was to create and maintain conditions of stability and security that would allow the people to pursue their livelihoods in a moderately prosperous society. Debates as to how best to achieve this ideal could be sharp, and different policy orientations predominated at various times, but the active role of the state in economic life was always a part of the mix.

This process of intellectual and cultural change went beyond the purely economic realm. In the preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, written in 1859, Marx notes that, in the social production of their existence, men enter into definite, necessary relations, which are independent of their will, namely, relations of production corresponding to a determinate stage of development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation on which there arises a legal and political superstructure and to which there correspond definite forms of social consciousness.31

In China, as early capitalism developed from the Song dynasty onward, new “forms of social consciousness” reflecting these new material realities also took shape. This became especially apparent by the Ming dynasty as a new merchant culture, drawing on particular elements within the broad discursive field of Confucian thought, articulated the hybridity of China’s elite society. The integration of elite elements based in manufacturing and trade with the long-established land-based literati/gentry yielded new ideas that revealed the mutual influence of new realities and older cultural beliefs and behaviors. Merchants engaged in practices of cultural patronage and aesthetic consumption in emulation of existing “gentlemanly” norms, endowing Buddhist religious institutions, building gardens, and assembling library collections. Confucian thought was influenced by market culture, as exemplified by the emergence of “ledgers of merit and demerit,” a form of moral accountancy in which individuals produced balance sheets for their conduct, or in the production of manuals of business practice that sought to navigate the complex relationship between the pursuit of profit and the maintenance of proper social relationships of community and stability. Imperial Confucianism remained the dominant ideology of the state, and within social elites, but it was adapted and adjusted to fit with the new material realities of commercial and manufacturing capitalism.32

The form of capitalism that emerged in China during the early modern period was marked by distinctive forms of power relations. Rather than evolving an antagonistic contradiction between an urban bourgeois class of merchants and manufacturers and a conservative feudal aristocracy of landowning great families, China developed a hybrid elite in that landed and commercial interests converged and functioned as the ruling class through the instrumentality of the imperial state. China’s historical itinerary did not lead to a bourgeois revolution taking power, but rather yielded a balance of elite forces and interests that remained hegemonic across repeated transitions in dynastic rule and that endeavored to shape the policies and practices of the imperial state in its own interests.

The government was tasked at a minimum with providing the security and stability needed to allow people to pursue their livelihoods, though the state could also play a more proactive role in economic life from time to time. Imperial dynasties built and maintained important infrastructure that facilitated long-distance trade, such as the Grand Canal and other water transport systems, or the imperial post roads that spanned the empire. Government monopolies in certain critical commodities were used to buffer some of the extremes of market supply and demand and curtail excessive profit seeking by private capital. Interventions in the all-important grain markets were deployed to sustain consumers in times of bad harvests and shortages. The imperial state was hardly a mercantilist actor, but it did contribute to the development and flourishing of China’s commercial capitalism.

VI

This understanding of China’s past can help illuminate some aspects of the country’s contemporary economic and political formations. China today is a society emerging from a long period of humiliation and oppression at the hands of Western imperialism, and from the turmoil and devastation of decades of revolutionary conflict and the Japanese invasion and occupation from 1937 to 1945. China’s early modern order proved unable to transcend its own limitations and was incapable of meeting the challenges of foreign intrusion and domination. By the late eighteenth century, the Qing empire had begun to face serious economic challenges, with population growth pushing against the limits of agricultural production within the established systems of land tenure and productive technologies. While the Qianlong emperor could still reject Britain’s overtures for free trade in 1793 based on China’s superior economic position, contradictions within the existing mode of production were intensifying.

The Industrial Revolution unleashed both immense productive capacities and powerful new military capabilities that, combined with the ideology of free trade promoted by the competitive imperatives of capitalist production and the ideas of Adam Smith and other political economists, transformed first the British and then other Europeans’ relations with the rest of the world in a wave of colonialist expansionism that fundamentally reconfigured the global economic and political order. China was subordinated to Western imperialism. Its long-vibrant commercial capitalism, already under pressure from internal difficulties, rapidly succumbed to foreign competition. European industrial capitalism reconfigured global relationships, creating a planetary division of labor within which China, though never made a colony of an individual Western power, assumed a subordinate role as a source of raw materials and as a market for European manufactured products. New Chinese capitalist elements began to appear in the late nineteenth century, but they struggled against the dominance of foreign businesses and finance. Western capital and the national governments that served it developed and maintained their power based on a monopoly of industrial productive technologies. The colonial system, which included China’s semicolonial position, preserved this monopoly until the Soviet Union began to develop its own industrial capacity in the 1920s.

In the countryside, the landed elite maintained much of its power and cultural preeminence, but, even there, wealth dwindled and prolonged instability eroded social cohesion. The imperial system staggered to its final collapse in the early twentieth century, and nearly four decades of political conflict and foreign invasion followed, destroying countless lives and further impoverishing the country. In the absence of a coherent national government, the extraction of surplus from agricultural production by local elites intensified and was exacerbated by warlord taxation and the corrupt practices of the nationalist regime. The Japanese invasion of 1937 and the war of resistance that lasted until 1945 brought further hardship and destruction to both urban and rural China.

Only with the victory of the revolution led by the Communist Party and the Red Army could the construction of a new modern China get underway. Land reform between 1948 and 1952 swept away the last vestiges of the old gentry landowning class in the countryside and created the conditions for building a new agriculture based on collective ownership and planned development.33 The industrial economy was nationalized in stages in the early 1950s, then began to grow through the deployment of capital from surpluses in both agriculture and manufacturing according to a series of five-year plans developed from the mid–1950s onward.

Experiments with varying forms of industrial management sought new ways to contribute to the development of a modern socialist economy.34 Aid and technical assistance from the Soviet Union and the Eastern European socialist states was crucial in the first decade of the People’s Republic. China was able begin developing a modern industrial sector distinct from the Western monopoly.

The path of socialist construction was contentious and deep divisions over how best to advance led to decades of struggle and conflict within the party and in society. The years from 1949 to 1979 saw successes and failures, advances and retreats. Dramatic improvements were made in public health, with average life expectancy rising significantly while infant mortality fell. National infrastructure in transportation and communication was massively expanded, as were reservoirs and other hydraulic resources, and overall economic growth averaged over 3 percent per year. Basic social services were provided and education was extended to most of the country’s young people.35

Nonetheless, by 1979 China remained a poor country as population growth negated some of the increases in production and a focus on heavy industry and infrastructure kept household consumption at basic levels. In a series of decisions at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the ’80s, the Communist Party decided to embark on a path of “reform and opening to the outside” (改革開放) aimed at rapidly developing the economy and reorienting production both to meeting the needs of domestic consumers and to creating an export sector that would generate further growth through profits and the accumulation of foreign exchange. At the heart of this process was the decision to use the mechanisms of the market to develop the productive economy. In other words, a certain amount of private capital would be allowed to function within the economy, in tandem with or parallel to the continuing operations of state-owned enterprises and other forms of socialist industry and agriculture. Foreign capital would be welcomed in joint ventures, initially limited to special economic zones but eventually spreading to the country at large.

This was not a blank check written to a new capitalist class. The decision to embrace the use of markets as a driver of development was premised on the ongoing key role of the Communist Party in China’s political and economic system. The party would continue to be the guiding force shaping policy and practice, and would oversee the country’s progress toward a level of prosperity where the needs of all people could be met and where a more equitable social order could be engendered. This is the vision that is characterized as socialism with Chinese characteristics, (Zhongguo tese shehui zhuyi, 中國特色社會主義).36

Though not without shortcomings and contradictions, China’s economy entered into an era of remarkable expansion as a result of these policies and practices. The Chinese economy’s growth rates often exceeded 10 percent over the next three decades and, in the pre-COVID years, were still growing by more than 6 percent annually. Productive capacity expanded rapidly and modern technologies were acquired, in part through joint venture partnerships with foreign capital. China also began to invest heavily in research and development to be able to pursue technological innovation with reduced reliance on foreign inputs. Hundreds of millions of people were lifted out of poverty, material standards of living rose dramatically, and China emerged on the world stage as an increasingly important player in global economic life.

China’s economy today is a hybrid of state and other collectively owned enterprises, ranging from huge national entities to county or township level factories or workshops (about 45 percent of asset ownership), and a private sector that includes both domestic businesses and international joint ventures (about 35 percent of asset ownership). Another 20 percent of businesses fall into an intermediate zone, with a blend of public and private ownership.37 State-owned enterprises, at both the central and local levels, form the core of the productive economy and infrastructure, predominate in banking and finance, and are the single largest source of government revenue, but the private sector has also assumed major proportions, with a number of world class corporations playing leading roles and an ever-growing number of billionaires. The private sector currently accounts for a little over half of all employment in industry, though more than 40 percent of China’s people still live and work in the agricultural sector, where land is owned by the state and leased to households. Production in both the industrial and agricultural sectors, by both public and private enterprises, is geared to a system of domestic and international markets. Much of China’s growth has come through its exports to the global economy, but domestic consumption is being increasingly expanded.

The rationale for the reform policies can be understood in part within the theoretical parameters of Marxist and Leninist experience. In the Communist Manifesto and many other writings, Marx and Frederick Engels were very clear on the power of capitalist markets to drive innovation and development. V. I. Lenin turned to market mechanisms under the New Economic Policies in the dark years after the Civil War in Russia to jumpstart the growth of the new Soviet economy. The creative power of markets always threatens to become a reckless monstrosity, like the demons conjured by the sorcerer’s apprentice. This is why the careful oversight of the party is critical to China’s future.38

In a discussion of the development of reform policies in November 2013, Xi Jinping set out the party’s position: “In 1992 the Party’s 14th National Congress stipulated that China’s economic reform aimed at establishing a socialist market economy, allowing the market to play a basic role in allocating resources under state macro control.” He noted that “there are still many problems. The market lacks order, and many people seek economic benefits through unjustified means.” He also emphasized that “we must unswervingly consolidate and develop the public economy, persist in the leading role of public ownership, give full play to the leading role of the state-owned economy, and incessantly increase its vitality, leveraging power and impact.”39 Over recent years, the party and the government have pursued an aggressive campaign against corruption, expanded regulatory oversight of industry and finance in both the public and private sectors, and promoted ideals of social responsibility and socialist values. These policies and practices suggest the complexity and dynamism of the relationship between the party, the state, and private economic actors.

Under the policies of reform, China now has capitalists, but it does not have a capitalist class that can control the state and shape it to its own interests. The practical effects of the leading role of the party can be seen in the ways in which the most dangerous aspects of capitalist economics are being buffered and constrained today. China continues to devote major resources to eliminating poverty, a key benchmark of which was achieved in November 2020 when the last few counties, in Guizhou province, that had lagged behind the internationally recognized definition of absolute poverty were finally designated as having emerged from that status. China must further improve the livelihoods of its people, but it is making steady progress in that direction. The serious environmental problems, which peaked in the first decade of the twenty-first century, are being addressed, and China’s commitment to be carbon neutral by 2060 is a clear statement of the priority of ongoing engagement with the ecology of the country.40 China is also developing a culture of what are sometimes called “patriotic entrepreneurs”— capitalists who understand that, in socialism with Chinese characteristics, they have a place within a unique social system, a hybrid of markets and planning, a blend of public and private ownership, and that they have a responsibility to contribute to the development not only of their own enterprises, but to the enhancement of the people’s livelihoods.41 The operations of the United Front Department of the party have been expanded in recent years as another means of managing the relationship between the party and other social and political elements.42 The party and the state thus are pursuing practical policies and actions to direct social resources to further development, and a program of cultural politics to ensure that the operations of private capital are integrated within the overall goals of socialist development.

The political and legal infrastructure of the People’s Republic, in particular the public ownership of land and the system of household registration, ensures that, just as there is no bourgeoisie, there is also no true proletariat. Workers in China are not compelled to sell their labor power in the marketplace because they have no property. The system of socialist ownership means that everyone in China has economic resources for their maintenance. Individuals are registered in their native places and have access to land as a place to live and to at least minimal social services such as education and health care. The importance of this was clearly demonstrated during the financial crisis of 2008 and beyond, when, with the downturn in demand for goods produced in and exported from China, some twenty million workers were laid off from factories in places like Shenzhen and Shanghai. These workers were not simply cast out and left to their own devices, but instead could return to their home villages, where they remained entitled to the support of the socialist system. As China adjusted to the new demand structure of the global economy, and as productive activity revived in the following years, workers could return to their former employment or seek new opportunities without having been reduced to poverty and immiseration. The provision of dibao (低保), the basic level of support in rural China, is not enough to maintain a truly comfortable way of life, which is why so many young people from the countryside have sought better economic opportunities in factory or construction work in the cities, but it did serve to bridge the period of unemployment caused by the global crisis.

Workers have also been able to use the mechanisms of socialist legality to pursue their economic interests within China’s rapidly developing economy. The All-China Federation of Trade Unions has represented workers across the country, and workers and citizens in general have exercised their rights to protest, petition, and litigate through the courts to address issues from wages and working conditions to corruption and abuse of power by officials to the dangers of environmental pollution. Beyond the operations of the union federation, Chinese workers have been militant in pursuing their interests through protests and wildcat strikes. Workers and other citizens take the law and their rights seriously and regularly engage in direct action to pursue their interests. This can be portrayed as a sign of alienation, but may perhaps more properly be seen as indicating their understanding and application of their civil powers.43 China’s socialist government and the Communist Party thus serve both to restrain the potential excesses and abuses of new capitalist elements and to maintain the central role of the working class within economic and social life.

This is not to say that workers who leave their native villages to seek employment in factories or on constructions sites are not acting out of economic motivations, nor that their labor power does not generate surplus value that is, at this stage in the developmental process, appropriated by private capital or even state-owned enterprises and other kinds of collectively owned enterprises. This is part of the bargain, part of the experiment on which the Communist Party embarked to develop China’s productive economy and accumulate wealth that leads first to a socialism of a “moderately prosperous society” (小康社會) and eventually to the level of material abundance that is the threshold and foundation of a communist future. There are risks and challenges along this path. The growth that has been achieved has not come without costs. The use of market mechanisms implied the acceptance of certain contradictions that are inherent in their operations. Inequality in the country has increased sharply, as, to paraphrase Deng Xiaoping, some people got rich first. Environmental stresses became a serious problem, with pollution of the air, water, and soil damaging people’s health and undermining the quality of life. Corruption became a critical legal and political issue. The Communist Party has made great efforts to address these contradictions, but also remains committed to the path of reform. The process of experimentation and innovation that has unfolded in the course of the reform era is sometimes called “crossing the river by feeling the rocks” (mozhe shitou guohe, 摸著石頭過河) and perhaps constitutes a course of “two steps forward, one step back” as history advances.

In her book The Transformation of Chinese Socialism, Lin Chun writes that “it is no easy task to ‘join the market in order to beat it’ via relinking, borrowing, and embracing.” She goes on to ask:

Might “private” capital be simultaneously “social” in a socialized market to serve public interests? Could such a market survive and eventually overcome the capitalist world market, and on what historical and institutional basis? Imposing these questions, we can recognize the truism that even a socialist society cannot avoid being “structurally dependent on capital.”… On the other hand, however, the preserved demarcation between capital and capitalism indicates the feasibility of preventing the logic of profit from colonizing the political, social, and cultural spheres—that is, if the right agency and institutions can be put in place.44

The historical outcome of China’s experiment with building a socialist market economy, “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” remains an open question. China’s remarkable success at coping with the COVID-19 pandemic and mobilizing social resources to address public health as a human right, in contrast to the catastrophic failures of capitalist, profit-seeking health care systems in the United States and the West, suggests that, while much work remains to be done, the country may indeed be on a path to socialist modernity. Looking at the history of the People’s Republic since 1949 provides one view of the complexities of China’s pursuit of a modern industrial, socialist system.

VII

Another way to consider the current reform era and the nature of China’s twenty-first-century political economy is in the longer perspective of China’s early modern capitalist history. The “Chinese characteristics” of China’s socialism can be understood in part as a structural and cultural redeployment of features we have seen in the Song-Qing era. The complex dialectic of the state seeking to both encourage and constrain the dynamism of capitalist markets that was pursued by imperial bureaucrats, to varying degrees at different times, resonates with the hybridity of public and private economic agents in China today. The shaping of a culturally specific political and economic consciousness through the interplay of market dynamics and select themes and currents within the broad field of Confucian thought and values, subordinating the single-minded pursuit of short-term profit to a longer perspective of socially responsible accumulation, perhaps foreshadowed today’s evocation of the ideal of “patriotic entrepreneurs.”

This does not mean that the People’s Republic is simply a new version of the old empire, old wine in new bottles, but rather that both the interplay of market forces and government policy in later imperial China and the present system of market socialism, or socialism with Chinese characteristics, constitute distinct modes of production that can be best understood in a historical materialist analysis that recognizes both their relationship to broader global processes of economic history and their developmental linkages to deep currents of continuity in Chinese material and cultural life. The key difference is of course the class nature of the state, which in imperial times was the instrument of class rule by the hybrid landed-commercial ruling elite, but is today, with the leading role of the Communist Party, the management committee for the building of a new social order, at least aspirationally, and to a significant extent, practically, based on the interests and wishes of the working class. This remains a work in progress, as history continues to move.

Appreciating the specificities of China’s history and its present path within the overall framework of a historical materialist perspective allows us to move beyond trying to assimilate all forms of capitalism, all paths toward socialism, all versions of early modernity, to a single universal template. It is the mode of analysis that must be universal, and the data must drive the conclusions. The analytical perspective derived from Capital and Marx’s other writings does not mean we need to seek and find the exact same totality in every place to be able to apply a precise definition of capitalism, and to fit the experience of different peoples in different places into a monolithic narrative flow. A nuanced application of Marx’s methods to the particularities of place and time will yield results of greater practical utility in both the understanding of the past and an engagement with contemporary developments.

Notes:

- ↩ See, for example, Yan Xuetong, Leadership and the Rise of Great Powers (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); Zhang Weiwei, The China Wave: Rise of a Civilizational State (Hackensack, NJ: World Century Publishing, 2012); Yukon Huang, Cracking the China Conundrum: Why Conventional Economic Wisdom is Wrong (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); Wang Hui, China’s Twentieth Century (London: Verso, 2016); Charles Horner, Rising China and Its Postmodern Fate (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2009).

- ↩ The argument that China has capitulated to a capitalist system has been made many times since the beginning of the reform era. See, inter alia, William Hinton, The Great Reversal: The Privatization of China, 1978–1989 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1990); Eli Friedman, “Why China Is Capitalist: Toward an Anti-Nationalist Anti-Imperialism,” Spectre, July 15, 2020.

- ↩ A basic overview is provided in Richard von Glahn, The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

- ↩ For a good account in English of Chinese writing about the Asiatic mode of production through the 1980s, see Timothy Brook, The Asiatic Mode of Production in China (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1989). Chinese scholarship on economic history and the question of the “sprouts of capitalism” includes, inter alia, 傅衣凌。明清時代商人及商業資本。北京:中華書局,2007;李伯重。多視角看江南經濟史(1250–1850),北京:三聯書局,2003;萬明,主編。晚明社會變遷:問題與研究。北京:商業印書館, 2005.

- ↩ Much writing on Chinese history continues to be organized on the basis of imperial dynasties. Broader categories are useful for understanding long-term trends and developments, yet there is not a consensus on the appropriate terminology. Most scholars accept the term antiquity, but some continue to refer to the middle period as medieval, while the term early modern is adopted by a growing number of scholars, but with varying period definitions. Some continue to prefer the term late imperial for this period. For a critical discussion of periodization and a characterization of the last thousand years of Chinese history, see Richard von Glahn, “Imagining Premodern China,” in The Song-Yuan-Ming Transition in Chinese History, ed. Paul Jakov Smith and Richard von Glahn (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2003), 35–70.

- ↩ Hsu Cho-Yun, Ancient China in Transition: An Analysis of Social Mobility, 722–222 BC (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1965).

- ↩ Zhang Chuanxi, “Growth of the Feudal Economy,” in The History of Chinese Civilization: Qin, Han, Wei, Jin, and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (221 BCE–581 CE), ed. Yuan Xingpei, Yan Wenming, Zhang Chuanxi, and Lou Yulie (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 139–95. The use of the term feudal in this chapter title reflects the continuing influence of Soviet-era orthodoxies.

- ↩ Joseph P. McDermott and Shiba Yoshinbu, “Economic Change in China, 960–1279,” in The Cambridge History of China, vol. 5, part 2, Sung China, 960–1279, ed. John W. Chaffee and Denis Twitchett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 321–436.

- ↩ Nicolas Tackett, The Destruction of the Medieval Chinese Aristocracy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2014).

- ↩ The use of the term gentry is problematic, given its derivation from European social history, but is conventionally established in Anglophone Chinese history and is retained here in tandem with literati to delineate the dual nature of the landowning elite as both local and imperial.

- ↩ Shiba Yoshinobu, Commerce and Society in Sung China (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, 1992); William Guanglin Liu, The Chinese Market Economy, 1000–1500 (Albany: SUNY Press, 2015); McDermott and Shiba, “Economic Change in China, 960–1279.”

- ↩ Joshua A. Fogel, Politics and Sinology: The Case of Naitō Konan (1866–1934) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).

- ↩ Joseph Stalin, “Dialectical and Historical Materialism” and Other Writings (Graphyco, 2020).

- ↩ Earlier efforts to situate China in relation to the European development of capitalism are summarized in Timothy Brook and Gregory Blue, eds., China and Historical Capitalism: Genealogies of Sinological Knowledge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). See also David Faure, China and Capitalism: A History of Business Enterprises in Modern China (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006). For an exploration of the history of capitalism on a global basis, using non-Marxist definitions including private property rights, contracts enforceable by third parties, markets with responsive prices, and supportive governments, see Larry Neal and Jefferey G. Williamson, The Cambridge History of Capitalism, vol. 1, The Rise of Capitalism: From Ancient Origins to 1848 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- ↩ Recent scholarship has highlighted the ways in which Marx also articulated, in Capital, the Grundrisse, and elsewhere, a recognition that the course of European economic history and development was not the only or inevitable path for all societies around the world. Kevin B. Anderson, Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Marcello Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx, An Intellectual Biography (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020).

- ↩ Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1 (London: Penguin Books, 1990).

- ↩ On the industrial complex at Jingdezhen, see Anne Gerritsen, The City of Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

- ↩ Valerie Hansen, Negotiating Daily Life in Traditional China: How Ordinary People Used Contracts, 600–1400 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995); Madeleine Zelin, Jonathan K. Ocko, and Robert Gardella, eds., Contract and Property in Early Modern China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004).

- ↩ Michael Marmé, Suzhou: Where the Goods of All Provinces Converge (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).

- ↩ G. William Skinner, ed., The City in Late Imperial China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1965).

- ↩ For an incisive discussion of the question of comparability, see Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 455–91.

- ↩ These features of commercial capitalism in China are comparable to those in Europe, as outlined in Jairus Banaji, A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket, 2020).

- ↩ Timothy Brook, “Communications and Commerce,” in The Cambridge History of China, vol. 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, part 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 579–707.

- ↩ Arturo Giraldez, The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleons and the Dawn of the Global Economy (Boulder: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015).

- ↩ Jie Zhao, Brush, Seal, and Abacus: Troubled Vitality in Late Ming China’s Economic Heartland, 1500–1644 (Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2018); Timothy Brook, The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

- ↩ Margherita Zanasi, Economic Thought in Modern China: Market and Consumption, c. 1500–1937 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

- ↩ Timothy Brook, Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late Ming China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard-Yen-Ching Institute, 1996).

- ↩ Karl Marx, Surveys from Exile (London: Verso, 2010), 254.

- ↩ William T. Rowe, Saving the World: Chen Hongmou and Elite Consciousness in Eighteenth Century China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002).

- ↩ Karl Marx, preface and introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1976), 3.

- ↩ Cynthia Joanne Brokaw, Ledgers of Merit and Demerit: Social Change and Moral Order in Late Imperial China (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016); Richard Lufrano, Honorable Merchants: Commerce and Self-Cultivation in Late Imperial China (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997).

- ↩ William Hinton, Fanshen: A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village (New York: Vintage, 1966).

- ↩ Franz Schurmann, Ideology and Organization in Communist China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966).

- ↩ Jean Chesneaux, China: The People’s Republic, 1949–1976 (New York: Pantheon, 1979).

- ↩ The phrase “socialism with Chinese characteristics” has itself gone through a process of transformation. It was originally developed in the 1950s in the context of Mao Zedong’s efforts to promote his vision of economic development as distinct from the Soviet experience. Deng Xiaoping redeployed the term in the 1980s and it has continued to be adapted to China’s ongoing policy developments. Under Xi Jinping, it has been expanded to become “socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era.”

- ↩ Nicholas Borst, “State-Owned Enterprises and Investing in China,” Seafarer, November 2019.

- ↩ Domenico Losurdo, “Has China Turned to Capitalism? Reflections on the Transition from Capitalism to Socialism,” International Critical Thought 7, no. 1 (2017): 15–31.

- ↩ Xi Jinping, The Governance of China, I (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2014), 83–86.

- ↩ Barbara Finamore, Will China Save the Planet? (Cambridge: Polity, 2018).

- ↩ “Chinese Entrepreneurs Urged to Show Patriotism,” Apple Daily, December 14, 2020.

- ↩ Takashi Suzuki, “China’s United Front Work in the Xi Jinping Era: Institutional Developments and Activities,” Journal of Contemporary East Asian Studies 8, no. 1 (2019): 83–98.

- ↩ Ching Kwan Lee, Against the Law: Labor Protests in China’s Rustbelt and Sunbelt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

- ↩ Lin Chun, The Transformation of Chinese Socialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 251–52.